Cotton-spinning machinery

Cotton-spinning machinery is machines which process (or spin) prepared cotton roving into workable yarn or thread.[1] Such machinery can be dated back centuries. During the 18th and 19th centuries, as part of the Industrial Revolution cotton-spinning machinery was developed to bring mass production to the cotton industry. Cotton spinning machinery was installed in large factories, commonly known as cotton mills.

| Bale breaker | Blowing room | |||||

| Willowing | ||||||

| Breaker scutcher | Batting | |||||

| Finishing scutcher | Lapping | Teasing | ||||

| Carding | Carding room | |||||

| Sliver lap | ||||||

| Combing | ||||||

| Drawing | ||||||

| Slubbing | ||||||

| Intermediate | ||||||

| Roving | Fine roving | |||||

| Mule spinning | Ring spinning | Spinning | ||||

| Reeling | Doubling | |||||

| Winding | Bundling | Bleaching | ||||

| Weaving shed | Winding | |||||

| Beaming | Cabling | |||||

| Warping | Gassing | |||||

| Sizing/slashing/dressing | Spooling | |||||

| Weaving | ||||||

| Cloth | Yarn (cheese) Bundle | Sewing thread | ||||

History

Spinning wheel

The spinning wheel was invented in the Islamic world by 1030. It later spread to China by 1090, and then spread from the Islamic world to Europe and India by the 13th century.[2]

Until the 1740s all spinning was done by hand using a spinning wheel. The state of the art spinning wheel in England was known as the Jersey wheel however an alternative wheel, the Saxony wheel was a double band treadle spinning wheel where the spindle rotated faster than the traveller in a ratio of 8:6, drawing on both was done by the spinners fingers.[3]

Lewis Paul and John Wyatt

In 1738 Lewis Paul and John Wyatt of Birmingham patented the Roller Spinning machine and the flyer-and-bobbin system, for drawing cotton to a more even thickness, using two sets of rollers that travelled at different speeds. This principle was the basis of Richard Arkwright's later water frame design. By 1742 Paul and Wyatt had opened a mill in Birmingham which used their new rolling machine powered by a donkey, this was not profitable and soon closed. A factory was opened in Northampton in 1743, with fifty spindles turning on five of Paul and Wyatt's machines, proving more successful than their first mill; this operated until 1764.

Lewis Paul invented the hand-driven carding machine in 1748. A coat of wire slips were placed around a card, which was then wrapped around a cylinder. Lewis' invention was later developed and improved by Richard Arkwright and Samuel Crompton, although the design came under suspicion after a fire at Daniel Bourn's factory in Leominster which used Paul and Wyatt's spindles. Bourn produced a similar patent in the same year.

Rev John Dyer of Northampton recognised the importance of the Paul and Wyatt cotton spinning machine in a poem in 1757:

A circular machine, of new design

In conic shape: it draws and spins a thread

Without the tedious toil of needless hands.

A wheel invisible, beneath the floor,

To ev'ry member of th' harmonius frame,

Gives necessary motion. One intent

O'erlooks the work; the carded wool, he says,

So smoothly lapped around those cylinders,

Which gently turning, yield it to yon cirue

Of upright spindles, which with rapid whirl

Spin out in long extenet an even twine.

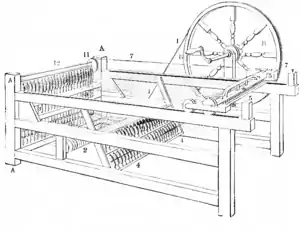

Spinning jenny

The spinning jenny is a multi-spool spinning wheel. It was invented circa 1764, its invention attributed to James Hargreaves in Stanhill, near Blackburn, Lancashire.[4] The spinning jenny was essentially an adaptation of the spinning wheel.[5]

Water frame

The Water frame was developed and patented by Arkwright in the 1770s. The roving was attenuated (stretched) by drafting rollers and twisted by winding it onto a spindle. It was heavy large scale machine that needed to be driven by power, which in the late 18th century meant by a water wheel.[6] Cotton mills were designed for the purpose by Arkwright, Jedediah Strutt and others along the River Derwent in Derbyshire. Water frames could only spin left.

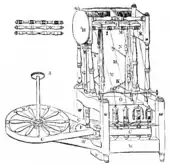

Spinning mule

The spinning mule or mule jenny was created in 1779 by Samuel Crompton. It was a combination of Arkwright's water frame and Hargreaves' spinning jenny. It was so named because it was a hybrid of these two machines. The mule consisted of a fixed frame containing a creel of bobbins holding the roving, connected through the headstock to a parallel carriage containing the spindles. It used an intermittent process:[7] On the outward traverse, the rovings were paid out, and twisted, and the return traverse, the roving was clamped and the spindles reversed taking up the newly spun thread. The rival machine, the throstle frame or ring frame was a continuous process, where the roving was drawn twisted and wrapped in one action. The spinning mule became self-acting (automatic) in 1830s. The mule was the most common spinning machine from 1790 until about 1900, but was still used for fine yarns until the 1960s. A cotton mill in 1890 would contain over 60 mules, each with 1320 spindles.[8]

Between the years 1824 and 1830 Richard Roberts invented a mechanism that rendered all parts of the mule self-acting, regulating the rotation of the spindles during the inward run of the carriage.

The Platt Brothers, based in Oldham, Greater Manchester were amongst the most prominent machine makers in this field of work.

At first this machine was only used to spin coarse and low-to-medium counts, but it is now employed to spin all counts of yarn.

Throstle

The Throstle frame was a descendant of the water frame. It used the same principles, was better engineered and driven by steam. In 1828 the Danforth throstle frame was invented in the United States. The heavy flyer caused the spindle to vibrate, and the yarn snarled every time the frame was stopped.[9] Not a success. It was named throstle, as the noise it made when running was compared to the song of the throstle (thrush).

Ring frame

1 Draughting rollers

2 Spindle

3 Attenuated roving

4 Thread guides

5 Anti-ballooning ring

6 Traveller

7 Rings

8 Thread on bobbin

The Ring frame is credited to John Thorp in Rhode Island in 1828/9 and developed by Mr. Jencks of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, who (Marsden 1884) names as the inventor.[9]

The bobbins or tubes may be filled from "cops", "ring spools" or "hanks", but a stop motion is required for each thread, which will come into operation immediately a fracture occurs.[10]

Break or open-end spinning

DREF friction spinning

Further processes

For many purposes, the threads as spun by the ring frame or the mule are ready for the manufacturer; but where extra strength or smoothness is required, as in threads for sewing, crocheting, hosiery, lace and carpets; also where multicoloured effects are needed, as in Grandrelle, or some special form of irregularity, as in corkscrewed, and knopped yarns, two or more single threads are compounded and twisted together. This operation is known as "doubling".[10]

See also

References

- Brown, Yvette (2023-05-02). "How Does a Cotton Spinning Machine Work? - Display Cloths". Retrieved 2023-08-07.

- Pacey, Arnold (1991) [1990]. Technology in World Civilization: A Thousand-Year History (First MIT Press paperback ed.). Cambridge MA: The MIT Press. pp. 23-24.

- Marsden 1884, p. 206

- Marsden 1884, p. 203

- Žmolek, Michael Andrew (2013). Rethinking the Industrial Revolution: Five Centuries of Transition from Agrarian to Industrial Capitalism in England. BRILL. p. 328. ISBN 9789004251793.

The spinning jenny was basically an adaptation of its precursor the spinning wheel

- Williams & Farnie 1992, p. 8

- Marsden 1884, p. 109

- Nasmith 1895, p. 109

- Marsden 1884, p. 298

- Fox 1911, p. 306.

Bibliography

- Marsden, Richard (1884). Cotton Spinning: its development, principles and practice. George Bell and Sons 1903. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- Marsden, ed. (1909). Cotton Yearbook 1910. Manchester: Marsden and Co. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- Nasmith, Joseph (1895). Recent Cotton Mill Construction and Engineering. London: John Heywood. p. 284. ISBN 1-4021-4558-6. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- Williams, Mike; Farnie (1992). Cotton Mills of Greater Manchester. Carnegie Publishing. ISBN 0-948789-89-1.

External links

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Fox, Thomas William (1911). "Cotton-spinning Machinery". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 301–307.

- Description of life in a Mule spinning mill