Craspedacusta sowerbii

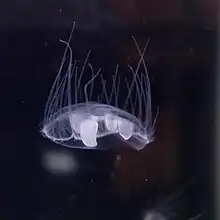

Craspedacusta sowerbii or peach blossom jellyfish[1] is a species of freshwater hydrozoan jellyfish, or hydromedusa cnidarian. Hydromedusan jellyfish differ from scyphozoan jellyfish because they have a muscular, shelf-like structure called a velum on the ventral surface, attached to the bell margin. Originally from the Yangtze basin in China, C. sowerbii is an invasive species now found throughout the world in bodies of fresh water.[2]

| Craspedacusta sowerbii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Class: | Hydrozoa |

| Order: | Limnomedusae |

| Family: | Olindiidae |

| Genus: | Craspedacusta |

| Species: | C. sowerbii |

| Binomial name | |

| Craspedacusta sowerbii Lankester, 1880 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Form

C. sowerbii medusae are about 20–25 mm (approximately 1 in.) in diameter, somewhat flatter than a hemisphere, and very delicate, when fully grown. They have a whorl of up to 400 tentacles tightly packed around the bell margin. Hanging down from the center of the inside of the bell is a large stomach structure called a manubrium, with a mouth-opening with four frilly lips. Circulation of nutrients is facilitated by four radial canals which originate at the edges of the stomach (manubrium), and which are also connected to a ring canal, located near the bell margin. Most of the body is transparent or translucent, with a whitish or greenish tinge. The (usually) four large flat sex organs (gonads) are attached to the four radial canals, and are usually opaque white. The many tentacles each contain thousands of cells called cnidocytes, which contain nematocysts (also known as cnidocysts), and are used to capture prey and pass it to the mouth. Food is taken in the mouth opening, and waste is finally expelled out of the same opening.

Habitat and distribution

C. sowerbii is native to the Yangtze basin in China, but has been introduced on every continent except for Antarctica.[2] It can for instance be found in most American states (no reports yet from Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, South Dakota, Alaska or Hawaii) and most Canadian provinces (no reports yet from Alberta or Saskatchewan).[3]

It is usually found in calm, freshwater reservoirs, lakes, impoundments, gravel pits or quarries. It has also been seen in slow-moving backwaters of river systems such as the Allegheny River, the Ohio River and the Tennessee River in the United States and the Wang Thong River of Thailand. It is not generally seen in fast flowing streams or rivers.

The medusa's appearance is sporadic and unpredictable from year to year. It is not uncommon for C. sowerbii to appear in a body of water where it had never been documented before, in very large numbers, and its appearance may even be reported on the local news.

On August 21, 2010, C. sowerbii was spotted and captured on the northwest corner of Falcon Lake in Manitoba, Canada. Scientists believe this was due to a heat wave in the Whiteshell Provincial Park area. It is proposed the C. sowerbii came to Falcon Lake on waterfowl originating from Star Lake, Manitoba, Canada. Falcon Lake along with Star Lake remain the only two confirmed sightings of C. sowerbii in Manitoba.[4]

C. sowerbii has been seen in Pennsylvanian lakes and reservoirs including Marsh Creek Lake, Downingtown/Eagle, PA Turnpike/Rt 100/Rt 401, SR 282 (2007,2008).[5]

It has been found in water reservoirs and artificial lakes in south-eastern Australia, including the Thorndon Park reservoir[6] and Lake Burley Griffin.[7]

It was reported in Panama in 1925, Chile in 1942, Argentina in 1950, Brazil in 1963, and in Uruguay in 1971.[8]

Since 2008 the freshwater jellyfish have been sighted every September and October in the Zhaojiaya Reservoir near Zhangjiajie, Hunan, China.[9]

It has been found in the Cauvery River and backwaters of the Hemavathi River in Karnataka, India[10] and in several lakes in Hungary.[11]

During the abnormal heat in the summer 2010 in Russia sightings of C. sowerbii were reported in the Moscow River.[12]

In July 2022, a population was discovered in a pond at Shawnee Park in Louisville, Kentucky.[13]

The jellyfish was discovered in 2023 in lake Korlatoš, near Sombor, Serbia

During the heatwave in July 2023, the jellyfish was found and reported in the Danube River in Vienna, Austria.

Feeding

C. sowerbii is a predator on zooplankton including daphnia and copepods. Prey is caught with their stinging tentacles. Drifting with its tentacles extended, the jelly waits for suitable prey to touch a tentacle. Once contact has been made, nematocysts on the tentacle fire into the prey, injecting poison which paralyzes the animal, and the tentacle itself coils around the prey. The tentacles then bring the prey into the mouth, where it is released and then digested.

Just like salt water jellyfish they do have stinging cells. However, these cnidocyte cells are used for paralyzing very tiny prey and have not been proven to have the capacity to pierce human skin.[14]

Life cycle

C. sowerbii begins life as a tiny polyp, which lives in colonies attached to underwater vegetation, rocks, or tree stumps, feeding and asexually reproducing during spring and summer. Some of these offspring are the sexually reproducing medusae. Fertilized eggs develop into small ciliated larvae called planulae. The planulae then settle to the bottom, and develop into polyps. However, the majority of C. sowerbii populations existing in the United States are either all male or all female, so there is no sexual reproduction in those populations.

During the cold winter months, polyps contract and enter dormancy as resting bodies called podocysts. It is believed that podocysts are transported by aquatic plants or animals to other bodies of water. Once conditions become favorable, they develop into polyps again.

References

- "freshwater jellyfish (Craspedacusta sowerbyi) - Species Profile".

- Didžiulis, Viktoras. "NOBANIS – Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet – Craspedacusta sowerbyi" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- Peard, Terry. "Distribution of the freshwater jellyfish". Archived from the original on 2008-07-28. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- "Families find Manitoba's first jellyfish". Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- "What is the distribution of the freshwater jellyfish in Pennsylvania". Dr. Terry Peard. Archived from the original on 2016-12-29. Retrieved 2016-12-29.

- "Tiny African jellyfish in S.A. reservoir". Mail (Adelaide, SA : 1912 - 1954). 1950-03-11. p. 3. Retrieved 2017-08-05.

- "Jellyfish live in lake". Canberra Times (ACT : 1926 - 1995). 1967-03-01. p. 1. Retrieved 2017-08-05.

- Parent, G.H (1982). "Une page d'histoire des sciences contemporaines : un siècle d'observations sur la méduse d'eau douce, Craspedacusta sowerbii Lank". Bulletin mensuel de la Société linnéenne de Lyon (in French). 51 (2): 47–63. doi:10.3406/linly.1982.10519. ISSN 0366-1326.

- "ZJJ Cili Zhaojiaya Reservoir Appeared Freshwater Jellyfish". Zhangjiajie City Information Center. Archived from the original on 2014-08-19. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- "Photographs of C. Sowerbii in India". Archived from the original on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

- "Az édesvízi medúza (Craspedacusta sowerbii Lankaster, 1880) magyarországi előfordulása | The freshwater jellyfish (Craspedacusta sowerbii Lankester, 1880) in Hungarian waters - REAL - az MTA Könyvtárának Repozitóriuma". Retrieved 2016-08-06.

- "Man nets seven jellyfish in Moscow River". RIA Novisti. Archived from the original on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2010-08-04.

- "'Mind blowing': How did thousands of jellyfish make it into this Louisville park's pond?". Retrieved 2022-08-23.

- "Will freshwater jellyfish sting me?". Archived from the original on 2012-07-22.

Romania

External links

- https://web.archive.org/web/20090922212421/http://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.asp?speciesID=1068 USGS' page about C. sowerbyi

- https://web.archive.org/web/20190719042938/http://freshwaterjellyfish.org/ An authoritative and detailed website about Craspedacusta sowerbyi

- https://web.archive.org/web/20190721110836/http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/mag/artdec99/fwjelly2.html

- https://web.archive.org/web/20190718162523/http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/mag/artnov99/fwjelly.html

- Kaeng Bang Rachan at Tourism Authority of Thailand (reference to freshwater jellyfish in the Wang Thong River in Thailand)

- GLANSIS Species FactSheet