Scyphozoa

The Scyphozoa are an exclusively marine class of the phylum Cnidaria,[2] referred to as the true jellyfish (or "true jellies").

| Scyphozoa Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cephea cephea | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Subphylum: | Medusozoa |

| Class: | Scyphozoa Götte, 1887 |

| Subgroups | |

The class name Scyphozoa comes from the Greek word skyphos (σκύφος), denoting a kind of drinking cup and alluding to the cup shape of the organism.[3]

Scyphozoans have existed from the earliest Cambrian to the present.[1]

Biology

Most species of Scyphozoa have two life-history phases, including the planktonic medusa or polyp form, which is most evident in the warm summer months, and an inconspicuous, but longer-lived, bottom-dwelling polyp, which seasonally gives rise to new medusae. Most of the large, often colorful, and conspicuous jellyfish found in coastal waters throughout the world are Scyphozoa.[4] They typically range from 2 to 40 cm (1 to 15+1⁄2 in) in diameter, but the largest species, Cyanea capillata can reach 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) across. Scyphomedusae are found throughout the world's oceans, from the surface to great depths; no Scyphozoa occur in freshwater (or on land).

As medusae, they eat a variety of crustaceans and fish, which they capture using stinging cells called nematocysts. The nematocysts are located throughout the tentacles that radiate downward from the edge of the umbrella dome, and also cover the four or eight oral arms that hang down from the central mouth. Some species, however, are instead filter feeders, using their tentacles to strain plankton from the water.[5]

Anatomy

Scyphozoans usually display a four-part symmetry and have an internal gelatinous material called mesoglea, which provides the same structural integrity as a skeleton. The mesoglea includes mobile amoeboid cells originating from the epidermis.

Scyphozoans have no durable hard parts, including no head, no skeleton, and no specialized organs for respiration or excretion.[6][7] Marine jellyfish can consist of as much as 98% water, so are rarely found in fossil form.

Unlike the hydrozoan jellyfish, Hydromedusae, Scyphomedusae lack a vellum, which is a circular membrane beneath the umbrella that helps propel the (usually smaller) Hydromedusae through the water. However, a ring of muscle fibres is present within the mesoglea around the rim of the dome, and the jellyfish swims by alternately contracting and relaxing these muscles.[8] The periodic contracting and relaxing propels the jellyfish through the water, allowing it to escape predation or catch its prey.

The mouth opens into a central stomach, from which four interconnected diverticula radiate outwards. In many species, this is further elaborated by a system of radial canals, with or without an additional ring canal towards the edge of the dome. Some genera, such as Cassiopea, even have additional, smaller mouths in the oral arms. The lining of the digestive system includes further stinging nematocysts, along with cells that secrete digestive enzymes.[5]

The nervous system usually consists of a distributed net of cells, although some species possess more organised nerve rings. In species lacking nerve rings, the nerve cells are instead concentrated into small structures called rhopalia. There are between four and sixteen of these small lobes arranged around the rim of the umbrella, where they coordinate the muscular action allowing the animal to move. Each rhopalium is typically associated with a pair of sensory pits, a statocyst, and sometimes a pigment-cup ocellus.[5]

Reproduction

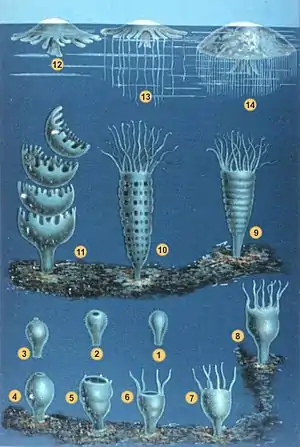

1–3 Larva searches for site

4–8 Polyp grows

9–11 Polyp strobilates

12–14 Medusa grows

Most species appear to be gonochorists, with separate male and female individuals. The gonads are located in the stomach lining, and the mature gametes are expelled through the mouth. After fertilization, some species brood their young in pouches on the oral arms, but they are more commonly planktonic.[5]

Growth and development

The fertilized egg produces a planular larva which, in most species, quickly attaches itself to the sea bottom. The larva develops into the hydroid stage of the lifecycle, a tiny sessile polyp called a scyphistoma. The scyphistoma reproduces asexually, producing similar polyps by budding, and then either transforming into a medusa, or budding several medusae off from its upper surface via a process called strobilation. The medusae are initially microscopic and may take years to reach sexual maturity.[5]

Commercial importance

Scyphozoa include the moon jelly Aurelia aurita,[9] in the order Semaeostomeae, and the enormous Nemopilema nomurai, in the order Rhizostomeae, found between Japan and China and which in some years causes major fisheries disruptions.

The jellyfish fished commercially for food are Scyphomedusae in the order Rhizostomeae.[10] Most rhizostome jellyfish live in warm water.[4]

Taxonomy

Although the Scyphozoa were formerly considered to include the animals now referred to as the classes Cubozoa and Staurozoa, they now include just three extant orders (two of which are in Discomedusae, a subclass of Scyphozoa).[11][12] About 200 extant species are recognized at present, but the true diversity is likely to be at least 400 species.[11]

Class Scyphozoa

- Subclass Coronamedusae

- Order Coronatae

- Family Atollidae

- Family Atorellidae

- Family Linuchidae

- Family Nausithoidae

- Family Paraphyllinidae

- Family Periphyllidae

- Subclass Discomedusae

- Order Rhizostomeae

- Suborder Daktyliophorae

- Family Catostylidae

- Family Lobonematidae

- Family Lychnorhizidae

- Family Rhizostomatidae

- Family Stomolophidae

- Suborder Kolpophorae

- Family Cassiopeidae

- Family Cepheidae

- Family Mastigiidae

- Family Thysanostomatidae

- Family Versurigidae

- Order Semaeostomeae

- Family Cyaneidae

- Family Drymonematidae[13]

- Family Pelagiidae

- Family Phacellophoridae

- Family Ulmaridae

References

- Liu, Yunhuan; Shao, Tiequan; Zhang, Huaqiao; Wang, Qi; Zhang, Yanan; Chen, Cheng; Liang, Yongchun; Xue, Jiaqi (2017). "A new scyphozoan from the Cambrian Fortunian Stage of South China". Palaeontology. 60 (4): 511–518. doi:10.1111/pala.12306.

- Dawson, Michael N. "The Scyphozoan". Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- Towle, Albert (1989). Modern biology. Austin, Texas: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 978-0030139192.

- Kramp, P. L. (1961). "Synopsis of the medusae of the world". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 40: 1–469. doi:10.1017/s0025315400007347.

- Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 139–149. ISBN 978-0-03-056747-6.

- Cartwright, P., Halgedahl, S.L., Hendriks, J.R., Jarrad, R.D., Marques, A.C., Collins, A.G., and Lieberman, B.S., 2007, Exceptionally preserved jellyfishes from the Middle Cambrian. PLOSONE Issue 10: e1121, p.1-7.

- Richards, H.G., 1947, Preservation of fossil jellyfish: Bulletin of the Geological Society of America, v. 58, p. 1221.

- Morris, M., and Fautin, D., 2001, Animal Diversity Web: University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, "Scyphozoa., Accessed: September 28, 2008.

- Berking S, Herrmann K (2007). "Compartments in Scyphozoa". Int. J. Dev. Biol. 51 (3): 221–8. doi:10.1387/ijdb.062215sb. PMID 17486542.

- Omori, Makoto; Eiji Nakano (2001). "Jellyfish fisheries in southeast Asia". Hydrobiologia. 451 (1/3): 19–26. doi:10.1023/A:1011879821323. S2CID 6518460.

- Daly, Brugler, Cartwright, Collins, Dawson, Fautin, France, McFadden, Opresko, Rodriguez, Romano & Stake (2007). The phylum Cnidaria: A review of phylogenetic patterns and diversity 300 years after Linnaeus. Zootaxa 1668: 127–182

- "Scyphozoa". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- Bayha, K. M., and M. N. Dawson (2010). New family of allomorphic jellyfishes, Drymonematidae (Scyphozoa, Discomedusae), emphasizes evolution in the functional morphology and trophic ecology of gelatinous zooplankton. The Biological Bulletin 219(3): 249–267

External links

- The Classification and Distribution of the Class Scyphozoa

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.