Croquet

Croquet (UK: /ˈkroʊkeɪ, -ki/ or US: /kroʊˈkeɪ/) is a sport[1][2] that involves hitting wooden or plastic balls with a mallet through hoops (often called "wickets" in the United States) embedded in a grass playing court.

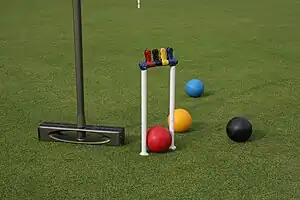

Modern croquet equipment | |

| Highest governing body | World Croquet Federation (WCF) (association and golf) United States Croquet Association (USCA) (6-wicket and 9-wicket) |

|---|---|

| First played | 1856 |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | No |

| Team members | Singles, doubles, and team events |

| Type | Mallet sport |

| Equipment | Mallet, balls, hoops or wickets |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | Only in 1900 Summer Olympics |

| Paralympic | No |

| World Games | No |

Its international governing body is the World Croquet Federation.

Variations

There are several variations of croquet currently played, differing in the scoring systems, order of shots, and layout (particularly in social games where play must be adapted to smaller-than-standard playing courts). Two forms of the game, association croquet (AC) and golf croquet (GC), have rules that are agreed upon internationally and are played in many countries around the world. The United States has its own set of rules for domestic games. Gateball, a sport that originated in Japan under the influence of croquet, is played mainly in East and Southeast Asia and the Americas, and can also be regarded as a croquet variant.

As well as club-level games, county-level tournaments and leagues, there are regular world championships and international matches between croquet-playing countries. The sport has particularly strong followings in the UK, US, New Zealand, Australia and Egypt; many other countries also play. Every four years, the top countries play in the World Team Championships in AC (the MacRobertson Shield) and GC (the Openshaw Shield). The current world rankings show England in top place for AC,[3] followed by Australia in second place, and New Zealand in third place, with the United States in fourth position. The same four countries appear in the top six of the GC country rankings,[4] below Egypt in top position, and with Spain at number six.

Croquet is popularly believed to be viciously competitive.[5] This may derive from the fact that (unlike in golf) players will often attempt to move their opponents' balls to unfavourable positions. However, purely negative play is rarely a winning strategy; successful players (in all versions other than golf croquet) will use all four balls to set up a break for themselves, rather than simply making the game as difficult as possible for their opponents. At championship-standard association croquet, players can often make all 26 points (13 for each ball) in two turns.

Croquet was an event at the 1900 Summer Olympics. Roque, an American variation on croquet, was an event at the 1904 Summer Olympics.

Beginning in 1894 Spalding Athletic Library issued official rules (with illustrations) as adopted by the National American Croquet Association.[6]

Association

Association croquet is an advanced game of croquet, played at levels up to international. It involves four balls teamed in pairs, with both balls going through every hoop for one pair to win. The game's distinguishing feature is the "croquet" shot: when certain balls hit other balls, extra shots are allowed. The six hoops are arranged three at each end of the court, with a centre peg.

One side takes the blue and black balls, the other takes red and yellow. At each turn, players can choose to play with either of their balls for that turn. At the start of a turn, the player plays a stroke. If the player either hits the ball through the correct hoop ("runs" the hoop), or hits another ball (a "roquet"), the turn continues.

Following a roquet, the player picks up his or her own ball and puts it down next to the ball that it hit. The next shot is played with the two balls touching: this is the "croquet stroke" from which the game takes its name. By varying the speed and angle at which the mallet hits the striker's ball, a good player can control the final position of both balls: the horizontal angle determines how far the balls diverge in direction, while the vertical angle and the amount of follow-through determine the relative distance that the two balls travel.

After the croquet stroke, the player plays a "continuation" stroke, during which the player may again attempt to make a roquet or run a hoop. Each of the other three balls may be roqueted once in a turn before a hoop is run, after which they become available to be roqueted again.

The winner of the game is the team who completes the set circuit of six hoops (and then back again the other way), with both balls, and then strikes the centre peg (making a total of 13 points per ball = 26).

Good players may make ‘breaks’ or ‘runs’ of several hoops in a single turn. The best players may take a ball round a full circuit in one turn. "Advanced play" (a variant of association play for expert players) gives penalties to a player who runs certain hoops in a turn, to allow the opponent a chance of getting back into the game; feats of skill such as triple peels or better, in which the partner ball (or occasionally an opponent ball) is caused to run a number of hoops in a turn by the striker's ball, help avoid these penalties.

A handicap system ("bisques") provides less experienced players a chance of winning against more formidable opponents. Players of all ages and both sexes compete on level terms.

The World Championships are organised by the World Croquet Federation (WCF)[7] and usually take place every two or three years. The 2023 championships took place in London; the winner was Robert Fulford. The current Women's Association Croquet World Champion (2023) is Debbie Lines of England.[8]

The English team won the last MacRobertson International Croquet Shield tournament, which is the major international test tour trophy in association croquet. It is contested every three to four years between Australia, England, the United States and New Zealand. Historically the British have been the dominant force, winning 14 out of the 22 times that the event has been held. In individual competition, the UK is often divided by subnational country (England, Scotland and Wales), while Northern Ireland joins with the Republic in an All Ireland association (as it does in several other sports).

The world's top 10 association croquet players as of October 2023 were Robert Fletcher (Australia), Robert Fulford (England), Paddy Chapman (New Zealand), Jamie Burch (England), Reg Bamford (South Africa), Matthew Essick (USA), Mark Avery (England), Simon Hockey (Australia), Harry Fisher (England), Jose Riva (Spain).[9]

Unlike most sports, men and women compete and are ranked together. Three women have won the British Open Championship: Lily Gower in 1905, Dorothy Steel in 1925, 1933, 1935 and 1936, and Hope Rotherham in 1960. While male players are in the majority at club level in the UK, the opposite is the case in Australia and New Zealand.[9]

The governing body in England is The Croquet Association, which has been the driving force of the development of the game. The laws and rules are now maintained by the World Croquet Federation.

Golf

In golf croquet, a hoop is won by the first ball to go through each hoop. Unlike association croquet, there are no additional turns for hitting other balls.

Each player takes a stroke in turn, each trying to hit a ball through the same hoop. The sequence of play is blue, red, black, yellow. Blue and black balls play against red and yellow. When a hoop is won, the sequence of play continues as before with all players competing for the next hoop. The winner of the game is the player/team who wins the most hoops.

Golf croquet is the fastest-growing version of the game,[10] owing largely to its simplicity and competitiveness. There is an especially large interest in competitive success by players in Egypt.[11] Golf croquet is easier to learn and play, but requires strategic skills and accurate play. In comparison with association croquet, play is faster and balls are more likely to be lifted off the ground.

In April 2013, Reg Bamford of South Africa beat Ahmed Nasr of Egypt in the final of the Golf Croquet World Championship in Cairo, becoming the first person to simultaneously hold the title in both association croquet and golf croquet.[12] As of 2023, the Golf Croquet World Champion was Matthew Essick (USA) and the Women's Golf Croquet World Champion was Jamie Gumbrell (Australia).

In 2018, two international championships open to both sexes were won by women: in May, Rachel Gee of England beat Pierre Beaudry of Belgium to win the European Golf Croquet championship,[13] and in October, Hanan Rashad of Egypt beat Yasser Fathy (also from Egypt) to win the World over-50s Golf Croquet championship.[14]

American six-wicket

The American-rules version of croquet, another six-hoop game, is the dominant version of the game in the United States and is also widely played in Canada. It is governed by the United States Croquet Association. Its genesis is mostly in association croquet, but it differs in a number of important ways that reflect the home-grown traditions of American "backyard" croquet.

Two of the most notable differences are that the balls are always played in the same sequence (blue, red, black, yellow) throughout the game, and that a ball's "deadness" on other balls is carried over from turn to turn until the ball has been "cleared" by scoring its next hoop. A Deadness Board is used to keep track of deadness on all four balls. Tactics are simplified on the one hand by the strict sequence of play, and complicated on the other hand by the continuation of deadness.[15]

A further difference is the more restrictive boundary-line rules of American croquet. In the American game, roqueting a ball out of bounds or running a hoop out of bounds causes the turn to end, and balls that go out of bounds are replaced only nine inches (23 cm) from the boundary rather than one yard (91 cm) as in association croquet.[15] "Attacking" balls on the boundary line to bring them into play is thus far more challenging.

Nine-wicket

Nine-wicket croquet, sometimes called "backyard croquet", is played mainly in Canada and the United States, and is the game most recreational players in those countries call simply "croquet". In this version of croquet, there are nine wickets, two stakes, and up to six balls. The course is arranged in a double-diamond pattern, with one stake at each end of the course. Players start at one stake, navigate one side of the double diamond, hit the turning stake, then navigate the opposite side of the double diamond and hit the starting stake to end. If playing individually (Cutthroat), the first player to stake out is the winner. In partnership play, all members of a team must stake out, and a player might choose to avoid staking out (becoming a Rover) in order to help a lagging teammate.[16]

Each time a ball is roqueted, the striker gets two bonus shots. For the first bonus shot, the player has four options:[16]

- From a mallet-head distance or less away from the ball that was hit ("taking a mallet-head")

- From a position in contact with the ball that was hit, with the striker ball held steady by the striker's foot or hand (a "foot shot" or "hand shot")

- From a position in contact with the ball that was hit, with the striker ball not held by foot or hand (a "croquet shot")

- From where the striker ball stopped after the roquet.

The second bonus shot ("continuation shot") is an ordinary shot played from where the striker ball came to rest.

An alternative endgame is "poison": in this variant, a player who has scored the last wicket but not hit the starting stake becomes a "poison ball", which may eliminate other balls from the game by roqueting them. A non-poison ball that roquets a poison ball has the normal options. A poison ball that hits a stake or passes through any wicket (possibly by the action of a non-poison player) is eliminated. The last person remaining is the winner.[17]

History

The oldest document to bear the word croquet with a description of the modern game is the set of rules registered by Isaac Spratt in November 1856 with the Stationers' Company of London. This record is now in the Public Record Office. In 1868, the first croquet all-comers meet was held at Moreton-in-Marsh, Gloucestershire and in the same year the All England Croquet Club was formed at Wimbledon, London.

Regardless when and by what route it reached the British Isles and the British colonies in its recognizable form, croquet is, like pall-mall and trucco, among the later forms of ground billiards, which as a class have been popular in Western Europe back to at least the Late Middle Ages, with roots in classical antiquity, including sometimes the use of arches and pegs along with balls and mallets or other striking sticks (some more akin to modern field hockey sticks).[18][19][20] By the 12th century, a team ball game called la soule or choule, akin to a chaotic version of hockey or football (depending on whether sticks were used), was regularly played in France and southern Britain between villages or parishes; it was attested in Cornwall as early as 1283.[21]

In the book Queen of Games: The History of Croquet,[22] Nicky Smith presents two theories of the origin of the modern game of croquet, which took England by storm in the 1860s and then spread overseas.

French origin theory

The first explanation is that the ancestral game was introduced to Britain from France during the 1660–1685 reign of Charles II of England, Scotland and Ireland, and was played under the name of paille-maille (among other spellings, today usually pall-mall), derived ultimately from Latin words for 'ball and mallet' (the latter also found in the name of the earlier French game, jeu de mail). This was the explanation given in the ninth edition of Encyclopædia Britannica, dated 1877.

In his 1801 book The Sports and Pastimes of the People of England, Joseph Strutt described the way pall-mall was played in England at the time:

"Pale-maille is a game wherein a round box[wood] ball is struck with a mallet through a high arch of iron, which he that can do at the fewest blows, or at the number agreed upon, wins. It is to be observed, that there are two of these arches, that is one at either end of the alley. The game of mall was a fashionable amusement in the reign of Charles the Second, and the walk in Saint James's Park, now called the Mall, received its name from having been appropriated to the purpose of playing at mall, where Charles himself and his courtiers frequently exercised themselves in the practice of this pastime."[23]

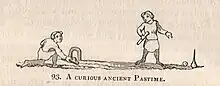

While the name pall-mall and various games bearing this name also appeared elsewhere (France and Italy), the description above suggests that the croquet-like games in particular were popular in England by the early 17th century. Some other early modern sources refer to pall-mall being played over a large distance (as in golf); however, an image in Strutt's 1801 book shows a croquet-like ground billiards game (balls on ground, hoop, bats, and peg) being played over a short, garden-sized distance. The image's caption describes the game as "a curious ancient pastime", confirming that croquet games were not new in early-19th-century England.

In Samuel Johnson's 1755 dictionary, his definition of "pall-mall" clearly describes a game with similarities to modern croquet: "A play in which the ball is struck with a mallet through an iron ring".[24] However, there is no evidence that pall-mall involved the croquet stroke which is the distinguishing characteristic of the modern game.

Irish origin theory

The second theory is that the rules of the modern game of croquet arrived from Ireland during the 1850s, perhaps after being brought there from Brittany, where a similar game was played on the beaches. Regular contact between Ireland and France had continued since the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169. By no later than the early 15th century, the game jeu de mail (itself ancestral to pall-mall and perhaps to indoor billiards) was popular in France, including in the courts of Henry II in the 16th century and Louis XIV of the 17th.

At least one version of it, rouët ('wheel') was a multi-ball lawn game. Records show a game called "crookey", similar to croquet, being played at Castlebellingham in County Louth, Ireland, in 1834, which was introduced to Galway in 1835 and played on the bishop's palace garden, and in the same year to the genteel Dublin suburb of Kingstown (today Dún Laoghaire) where it was first spelt as "croquet". There is, however, no pre-1858 Irish document that describes the way game was played, in particular, there is no reference to the distinctive croquet stroke,[25] which is described above under "Variations: Association". The noted croquet historian Dr Prior, in his book of 1872, makes the categoric statement "One thing only is certain: it is from Ireland that croquet came to England and it was on the lawn of the late Lord Lonsdale that it was first played in this country." This was about 1851.[26]

John Jaques apparently claimed in a letter to Arthur Lillie in 1873 that he had himself seen the game played in Ireland, writing "I made the implements and published directions (such as they were) before Mr. Spratt [mentioned above] introduced the subject to me."[27] Whatever the truth of the matter, Jaques certainly played an important role in popularising the game, producing editions of the rules in 1857, 1860, and 1864.

Heyday and decline

Croquet became highly popular as a social pastime in England during the 1860s. It was enthusiastically adopted and promoted by the Earl of Essex who held lavish croquet parties at Cassiobury House, his stately home in Watford, Hertfordshire, and the Earl even launched his own Cassiobury brand croquet set.[28][29] By 1867, Jaques had printed 65,000 copies of his Laws and Regulations of the game. It quickly spread to other Anglophone countries, including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, and the United States. No doubt one of the attractions was that the game could be played by both sexes; this also ensured a certain amount of adverse comment.

It is no coincidence that the game became popular at the same time as the cylinder lawn mower, since croquet can only be played well on a lawn that is flat and finely-cut.

By the late 1870s, however, croquet had been eclipsed by another fashionable game, lawn tennis, and many of the newly created croquet clubs, including the All England Club at Wimbledon, converted some or all of their lawns into tennis courts.

There was a revival in the 1890s, but from then onwards, croquet was always a minority sport, with national individual participation amounting to a few thousand players. The All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club still has a croquet lawn, but has not hosted any significant tournaments. Its championship was won 38 times by Bernard Neal. The English headquarters for the game is now in Cheltenham.

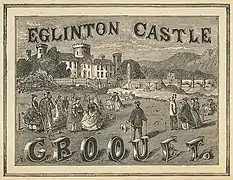

The earliest known reference to croquet in Scotland is the booklet The Game of Croquet, its Laws and Regulations which was published in the mid-1860s for the proprietor of Eglinton Castle, the Earl of Eglinton. On the page facing the title page is a picture of Eglinton Castle with a game of "croquet" in full swing.[30]

The croquet lawn existed on the northern terrace, between Eglinton Castle and the Lugton Water. The 13th Earl developed a variation on croquet named Captain Moreton's Eglinton Castle croquet, which had small bells on the eight hoops "to ring the changes", two pegs, a double hoop with a bell and two tunnels for the ball to pass through. In 1865 the 'Rules of the Eglinton Castle and Cassiobury Croquet' was published by Edmund Routledge. Several incomplete sets of this form of croquet are known to exist, and one complete set is still used for demonstration games in the West of Scotland.[30]

Glossary of terms

- Backward ball

- The ball of a side that has scored fewer hoops (compare with 'forward ball').[31]

- Ball-in-hand

- A ball that the striker can pick up to change its position, for example:

- any ball when it leaves the court has to be replaced on the yard-line

- the striker's ball after making a roquet must be placed in contact with the roqueted ball

- the striker's ball when the striker is entitled to a lift.[32]

- Ball in play

- A ball after it has been played into the game, which is not a ball in hand or pegged out.[32]

- Baulk

- An imaginary line on which a ball is placed for its first shot in the game, or when taking a lift. The A-baulk coincides with the western half of the yard line along the south boundary; the B-baulk occupies the eastern half of the north boundary yard line.[32]

- Bisque, half-bisque

- A bisque is a free turn in a handicap match. A half-bisque is a restricted handicap turn in which no point may be scored.[32]

- Break down

- To end a turn by making a mistake.[31]

- Cannon

- In association croquet, a shot which results after a roqueted ball comes to rest in contact with another ball on the lawn. The laws allow for this third ball to also be moved on the resulting croquet stroke, staying in touch with the roqueted ball (on which the striker is now ball-in-hand). The croquet stroke with the three balls in contact is referred to as a "cannon".[33]

- Continuation stroke

- Either the bonus stroke played after running a hoop in order or the second bonus stroke played after making a roquet.[32]

- Corner cannon

- In association croquet, a cannon taken from a corner of the court. Corner cannons occur a good deal more frequently than other cannons because skilled players seek them out as a way of getting a ball out of a corner and into a break. The corner is a fairly large target into which to rush and set up a corner cannon. [34]

- Croquet stroke

- A stroke taken after making a roquet, in which the striker's ball and the roqueted ball are placed together in contact.[32]

- Double tap

- A fault in which the mallet makes more than one audible sound when it strikes the ball.[32]

- Dolly rush

- A rush with a very short distance (a foot or less) between the balls. A dolly rush is easy to control and is generally considered quite desirable.

- Forward ball

- The ball of a side that has scored more hoops (compare with 'backward ball').[31]

- Hit In

- To make a roquet, usually at distance, which starts a break.

- Hoop

- Metal U-shaped gate pushed into ground.[32] (Also called a wicket in the US, which is of the same etymology as wicket gate[35]).[36]

- Leave

- The position of the balls after a successful break, in which the striker is able to leave the balls placed so as to make life as difficult as possible for the opponent.[31]

- Lift

- A turn in which the player is entitled to remove the ball from its current position and play instead from either baulk line. A lift is permitted when a ball has been placed by the opponent in a position where it is wired from all other balls, and also in advanced play when the opponent has completed a break that includes hoops 1-back or 4-back.[32]

- Object ball

- A ball which is going to be rushed.

- Peg out

- To cause a rover ball to strike the peg and conclude its active involvement in the game.[32]

- Peel

- To send a ball other than the striker's ball through its target hoop.[32]

- Pioneer

- A ball placed in a strategic position near the striker's next-but-one or next-but-two hoop, to assist in running that hoop later in the break.

- Primary colours or first colours

- The main croquet ball colours used which are blue, red, black and yellow (in order of play). One player or team plays blue and black, the other red and yellow.[32]

- Push

- A fault when the mallet pushes the striker's ball, rather than making a clean strike.[32]

- Roquet

- (Second syllable rhymes with "play".) When the striker's ball hits a ball that he is entitled to then take a croquet shot with. At the start of a turn, the striker is entitled to roquet all the other three balls once. Once the striker's ball goes through its target hoop, it is again entitled to roquet the other balls once.[32]

- Rover ball

- A ball that has run all 12 hoops and can be pegged out.[32]

- Rover hoop

- The last hoop, indicated by a red top bar. The first hoop has a blue top.[32]

- Run a hoop

- To send the striker's ball through a hoop. If the hoop is the hoop in order for the striker's ball, the striker earns a bonus stroke.[32]

- Rush

- A roquet when the roqueted ball is sent to a specific position on the court, such as the next hoop for the striker's ball or close to a ball that the striker wishes to roquet next.[31]

- Scatter shot

- A continuation stroke used to hit a ball which may not be roqueted in order to send it to a less dangerous position.[31]

- Secondary colours

- (also known as second colours or alternate colours)[32] The colours of the balls used in the second game played on the same court in double-banking: green, pink, brown and white (in order of play). Green and brown versus pink and white, are played by the same player or pair.[32]

- Sextuple peel (SXP)

- To peel the partner ball through its last six hoops in the course of a single turn. Very few players have achieved this feat, but it is being seen increasingly at championship level.[31]

- Tice

- A ball sent to a location that will entice an opponent to shoot at it but miss.[31]

- Triple peel (TP)

- To send a ball other than the striker's ball through its last three hoops, and then peg it out. See also Triple Peel. A variant is the Triple Peel on Opponent (TPO), where the opponent's ball, rather than the partner ball, is peeled. The significance of this manoeuvre is that in advanced play, making a break that includes the tenth hoop (called 4-back) is penalized by granting the opponent a lift (entitling him to take the next shot from either baulk line). Therefore, many breaks stop voluntarily with three hoops and the peg still to run.[31]

- Wired

- When a hoop or the peg impedes the path of a striker's ball, or the swing of the mallet. A player will often endeavour to finish a turn with the opponent's balls wired from each other.[31]

- Yard line

- An imaginary line one yard (0.91 m) from the boundary. Balls that go off the boundary are generally replaced on the yard line (but if this happens on a croquet stroke, the turn ends).[32]

In art and literature

The way croquet is depicted in paintings and books says much about popular perceptions of the game, though little about the reality of modern play.

- In 1868 a song titled Croquet (essentially anonymous: by M.B.C.S and W.O.F.) was included in a popular song book by W. O. Perkins, The Golden Robin (Pub. Oliver Ditson & Company, New York). ("Upon the smoothly shaven lawn, Beneath the skies of May, Oh, boys and girls, this merry morn, Come out and play Croquet ..."); there are four full verses.

- Winslow Homer,[37] Édouard Manet,[38] and Pierre Bonnard[38] all have paintings titled The Croquet Game.

- Norman Rockwell often depicted the game, including in his painting Croquet.

- Edward Gorey's The Epiplectic Bicycle features illustrations of the main characters playing with croquet mallets.[39]

- Croquet is popular pastime of Leo Tolstoy's Anna Karenina characters.

- H. G. Wells wrote The Croquet Player which uses croquet as a metaphor for the way in which people confront the very problem of their own existence.

- Lewis Carroll featured a nonsense version of the game in the popular children's novel Alice's Adventures in Wonderland: a hedgehog was used as the ball, a flamingo as the mallet, and playing cards as the hoops.

- In the Thursday Next series of novels, notably Something Rotten, Jasper Fforde depicts an alternative world in which croquet is a brutal mass spectator sport.

- The cover of the 1971 Genesis album Nursery Cryme shows Cynthia, a character in the song "Musical Box" holding a croquet mallet with a few heads on the playing field including another character of the song Henry's head that she removed with said mallet.

- In Stephen King's 1977 novel The Shining, the main character, Jack Torrance, uses a croquet mallet to chase and attack the other characters.[40] The 1997 miniseries features the use of croquet however, Stanley Kubrick's 1980 film adaptation uses a fire axe instead.[40]

- In the 1980s geography game Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego?, one of the characters, Fast Eddie B, is described as a "world class croquet player", and two other gang members, Ihor Ihorovich and Scar Graynolt, also play the sport.

- In the 1988 film Heathers, Veronica (Winona Ryder) and her friends, the Heathers, are depicted as playing croquet,[41] though at the beginning, the Heathers are playing croquet to hit Veronica on the head. Croquet mallets also feature in the publicity posters for Heathers: The Musical.

- Croquet is featured prominently in the music video for "I'm Not Okay (I Promise)" by My Chemical Romance.

- Croquet is featured in the novel Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck wherein the Joads stay at the government camp in Weedpatch, Ca.[42]

Clubs

About 200 croquet clubs across the United States are members of the United States Croquet Association.[43]

Many colleges have croquet clubs as well, such as The University of Virginia, The University of Chicago, Pennsylvania State University,[44] Bates College, SUNY New Paltz, Harvard University, and Dartmouth College. Notably, St. John's College and the US Naval Academy engage in a yearly match in Annapolis, Maryland. Both schools also compete at the collegiate level and the rivalry continues to be an Annapolis tradition, attracting thousands of spectators each April.

In England and Wales, there are around 170 clubs affiliated with the Croquet Association.[45] The All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club at Wimbledon is famous for its lawn tennis tournament, but retains an active croquet section. There are also clubs in many universities and colleges, with an annual Varsity match being played between Oxford and Cambridge.[46] With over 1800 participants, the 2011 Oxford University "Cuppers" (inter-college) tournament claimed to be not only the largest croquet tournament ever, but the largest sporting event in the university's history.[47]

There are 112 clubs in New Zealand, affiliated with 19 associations. These are governed by Croquet New Zealand.[48]

See also

References

- The Croquet Association (CA), the national governing body for the sport of Croquet in England

- Oxford Croquet.com, "Croquet is a satisfying sport utilising tactics and touch in equal measure"

- "WCF World Team Rankings". World Croquet Federation. 23 December 2021.

- "WCF World Team Rankings". World Croquet Federation. 15 January 2022.

- "So they left the subject and played croquet, which is a very good game for people who are annoyed at each other, giving many opportunities for venting rancour." —Rose Macaulay, The Towers of Trebizond

- Buffalo Sunday Morning News, NY, July 1, 1894. Retrieved Dec 16, 2020

- "WCF World Championships". World Croquet Federation. 23 December 2021.

- "Women's World Championship". Croquet Records Website. 12 October 2023.

- Williams, Chris. "Croquet Grading System". Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- Carter, Kevin (2007). "Older, Wealthier and with a bit to Think about". The Croquet Association. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- Williams, Elizabeth (21 July 2008). "Egypt v Rest of World GC Event". Roehampton Club: The Croquet Association.

- King, Tim (28 April 2013). "Reg Bamford won the WCF GC Championship to become the first AC & GC World Champion". Cairo: The Croquet Association. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- "Rachel Gee won the European GC Championship". The Croquet Association. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "Croquet Scores: the 3rd Over 50 Golf Croquet World Championship". Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Plummer, Ian (1 January 2011). "Association vs US (6-wicket) Rules Croquet". Oxford Croquet.

- "9-Wicket Croquet: Backyard Croquet: Basic Rules". www.9wicketcroquet.com.

- "9-Wicket Croquet: Backyard Croquet: Challenging Options". www.9wicketcroquet.com.

- Shamos, Mike (1999). The New Illustrated Encyclopedia of Billiards. New York: Lyons Press. p. 117. ISBN 9781558217973.

- Clare, Norman (1996) [1985]. Billiards and Snooker Bygones (amended ed.). Princes Risborough, England: Shire Publications. p. 5. ISBN 0-85263-730-6.

- Stein, Victor; Rubino, Paul (2008). The Billiard Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). New York: Balkline Press. pp. 2, 4, 5, 14, 27. ISBN 978-0-615-17092-3. (First ed. pubd. 1994.)

- Elliot-Binns, L. E. Medieval Cornwall. London: Methuen & Co.

- Smith, Nicky (1991). Queen of Games: The History of Croquet. George Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-81176-2.

- Strutt, Joseph (1810). Sports and Pastimes of the People of England. Methuen. p. 96 – via Internet Archive.

- Johnson, Samuel; Walker, John; Jameson, Robert S. (1828). A dictionary of the English language. p. 519.

- Prichard, D. M. C. (1981). The History of Croquet. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-30759-9.

- Martin, Clive; Williams, Simon (2004). A Brief History of Croquet in Ireland.

- Lillie, Arthur (1897). Croquet: Its History, Rules, and Secrets. Longmans, Green. p. 29.

- "History". WatfordCroquet.org.uk. Watford Cassiobury Croquet Club. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- Reid, Mayne (1869). Croquet, etc. p. 46.

- "Introduction". Edinburgh Croquet Club. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- Hawkins, James (2010). Complete Croquet: A Guide to Skills, Tactics, and Strategy. Crowood Press. ISBN 978-1-84797-168-5.

- , 7th Edition, World Croquet Federation.

- Hutchinson, John. "The Cannon in Association Croquet".

- Kroeger, Bob. "Croquet - Corner Cannons".

- Company, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing. "The American Heritage Dictionary entry: wicket". ahdictionary.com. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- Association, United States Croquet. "United States Croquet Association – Introduction". www.croquetamerica.com. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- "Winslow Homer: The Croquet Game". Yale University Art Gallery. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- White, Laura (11 February 2015), "The "Queer-Looking Party" Challenge to Family in Alice", in Dau, Duc; Preston, Shale (eds.), Queer Victorian Families: Curious Relations in Literature, Taylor & Francis, p. 34, ISBN 9781317647065

- Ortiz, Aimee (22 February 2013). "Five Edward Gorey stories that everyone should read". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- Rawlings, Nate (17 June 2011). "Top 10 Worst Fictional Fathers". Time. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- Gardner, Abby (30 December 2019). "Everything You Didn't Know About Heathers". Glamour. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- Nealand, Daniel (Winter 2008). "Archival Vintages for The Grapes of Wrath". Prologue. 40 (4). Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- "Clubs Directory". United States Croquet Association. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- "Penn State Club Sports". Archived from the original on 30 October 2011.

- "Clubs and Federations". The Croquet Association. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- "Varsity Archive". Oxford University Croquet Club. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- "Oxford University Croquet Club - Welcome!". Users.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- "Croquet New Zealand - About Us". Croquet New Zealand. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

External links

- A Synopsis of the Laws of Association Croquet, from Oxford Croquet

- Synopsis of American Croquet, from the United States Croquet Association

- The official rules of Backyard Croquet (nine-wicket layout), from the United States Croquet Association

- Official Rules of Garden Croquet (British six-hoop garden croquet)

- Croquet Rules and Regulations, from Croquet.com

- The Croquet Association Jargon List

- Arkley Croquet Collection – An exceptional selection of paintings, cartoons and photographs depicting the game of croquet, from UBC Library Digital Collections

- Checklist of Croquet Books and Pamphlets, 1853 to 2002