Pierre Bonnard

Pierre Bonnard (French: [bɔnaʁ]; 3 October 1867 – 23 January 1947) was a French painter, illustrator and printmaker, known especially for the stylized decorative qualities of his paintings and his bold use of color.[1] A founding member of the Post-Impressionist group of avant-garde painters Les Nabis,[2] his early work was strongly influenced by the work of Paul Gauguin, as well as the prints of Hokusai and other Japanese artists. Bonnard was a leading figure in the transition from Impressionism to Modernism. He painted landscapes, urban scenes, portraits and intimate domestic scenes, where the backgrounds, colors and painting style usually took precedence over the subject.[3][4]

Pierre Bonnard | |

|---|---|

%252C_c.1899%252C_Mus%C3%A9e_d'Orsay%252C_restaur%C3%A9e.jpg.webp) Bonnard, c. 1899 | |

| Born | 3 October 1867 Fontenay-aux-Roses, Seine, France |

| Died | 23 January 1947 (aged 79) La Route de Serra Capeou, Le Cannet, Alpes-Maritimes, France |

| Known for | Painter |

| Movement | Post-Impressionism, Les Nabis, Intimism |

| Signature | |

Early life and education

Pierre Bonnard was born in Fontenay-aux-Roses, Hauts-de-Seine on 3 October 1867. His mother, Élisabeth Mertzdorff, was from Alsace. His father, Eugène Bonnard, was from the Dauphiné, and was a senior official in the French Ministry of War. He had a brother, Charles, and a sister, Andrée, who in 1890 married the composer Claude Terrasse.[5]

He received his education in the Lycée Louis-le-Grand and Lycée Charlemagne in Vanves. He showed a talent for drawing and water colors, as well as caricatures. He painted frequently in the gardens of his parents' country home at Le Grand-Lemps near La Côte-Saint-André in the Dauphiné. He also showed a strong interest in literature.[6] He received his baccalaureate in the classics, and, to satisfy his father, between 1886 and 1887 earned his license in law, and began practicing as a lawyer in 1888.[7][8]

While he was studying law, he attended art classes at the Académie Julian in Paris.[9][10] At the Académie Julien he met his future friends and fellow artists, Paul Sérusier, Maurice Denis, Gabriel Ibels and Paul Ranson.[11]

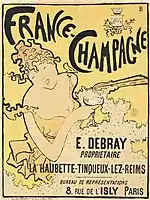

In 1888, Bonnard was accepted by the École des Beaux-Arts, where he met Édouard Vuillard and Ker Xavier Roussel. He also sold his first commercial work of art, a design for poster for France-Champagne, which helped him convince his family that he could make a living as an artist. His first studio was on the rue Lechapelais.[11]

Personal life

From 1893 until her death, Bonnard lived with Marthe de Méligny (1869–1942), and she was the model for many of his paintings, including many nudes. Her birth name was Maria Boursin, but she had changed it before she met Bonnard. They married in 1925. In the years before their marriage, Bonnard had love affairs with two other women, who also served as models for some of his paintings, Renée Monchaty (the partner of the American painter Harry Lachmann) and Lucienne Dupuy de Frenelle, the wife of a doctor; it has been suggested that Bonnard may have been the father of Lucienne's second son. Renée Monchaty committed suicide shortly after Bonnard and de Méligny married.[12]

Early career – the Nabis

Bonnard received pressure from a different direction to continue painting. While he had received his license to practice law in 1888, he failed in the examination for entering the official registry of lawyers.[13] Art was his only option. After the summer holidays, he joined with his friends from the Academy Julien to form Les Nabis, an informal group of artists with different styles and philosophies but common artistic ambitions. As he later wrote, Bonnard was entirely unaware of the impressionist painters, or of Gauguin and other new painters.[13] His friend Paul Sérusier showed him a painting on a wooden cigar box he made after visiting Paul Gauguin at Pont-Aven, using patches of pure color in the style of Gauguin. In 1890, Denis, at age twenty, formalized the doctrine in which a painting was considered "a surface plane covered with colors assembled in a certain order."[14]

Some of the Nabis had highly religious, philosophical or mystical approaches to their paintings, but Bonnard remained more cheerful and unaffiliated. The painter-writer Aurelien Lugné-Poe, who shared a studio at 28 rue Pigalle with Bonnard and Vuillard, wrote later, "Pierre Bonnard was the humorist among us; his nonchalant gaiety, and humor expressed in his productions, of which the decorative spirit always preserved a sort of satire, from which he later departed."[15]

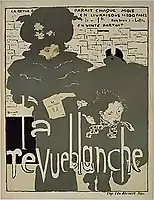

In 1891, he met Toulouse-Lautrec and, in December 1891, showed his work at the annual exhibition of the Société des Artistes Indépendants. In the same year, Bonnard also began an association with La Revue Blanche, for which he and Édouard Vuillard designed a frontispiece.[16] In March 1891, his work was displayed with the work of the other Nabis at the Le Barc de Boutteville.[11]

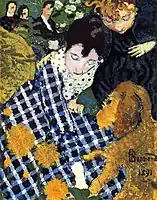

The style of Japanese graphic arts became an important influence on Bonnard. In 1893, a major exposition of works of Utamaro and Hiroshige was held at the Durand-Ruel Gallery, and the Japanese influence, particularly the use of multiple points of view, and the use of bold geometric patterns in clothing, such as checkered blouses, began to appear in his work. Because of his passion for Japanese art, his nickname among the Nabis became Le Nabi le trés japonard.[11]

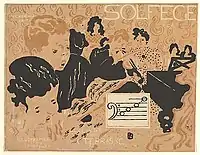

He devoted an increasing amount of attention to decorative art, designing furniture, fabrics, fans and other objects. He continued to design posters for France-Champagne, which gained him an audience outside the art world. In 1892, he began creating lithographs, and painted Le Corsage a carreaux and La Partie de croquet. He also made a series of illustrations for the music books of his brother-in-law, Claude Terrasse.

In 1894, he turned in a new direction and made a series of paintings of scenes of the life of Paris. In his urban scenes, the buildings and even animals were the focus of attention; faces were rarely visible. He also made his first portrait of his future wife, Marthe, whom he married in 1925.[11] In 1895, he became an early participant of the movement of Art Nouveau, designing a stained glass window, called Maternity, for Tiffany.[11]

In 1895, he had his first individual exposition of paintings, posters and lithographs at the Durand-Ruel Gallery. He also illustrated a novel, Marie, by Peter Nansen, published in series by in La Revue Blanche. The following year he participated in a group exposition of Nabis at the Amboise Vollard Gallery. In 1899, he took part in another major exposition of works of the Nabis.[11]

Woman with a Dog (1891), Clark Art Institute. The checked blouse was inspired by Japanese prints.

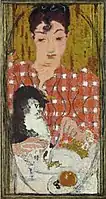

Woman with a Dog (1891), Clark Art Institute. The checked blouse was inspired by Japanese prints. Checkered Blouse (1892), a portrait of his sister Andrée Terrasse, with her cat

Checkered Blouse (1892), a portrait of his sister Andrée Terrasse, with her cat_by_Pierre_Bonnard.JPG.webp) The Parade (1892), one of several colorful paintings of Paris street performers

The Parade (1892), one of several colorful paintings of Paris street performers Two Dogs in a Deserted Street (1894), oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art

Two Dogs in a Deserted Street (1894), oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art The Omnibus (1895)

The Omnibus (1895) Dancers (1896)

Dancers (1896)

Later years (1900–1938)

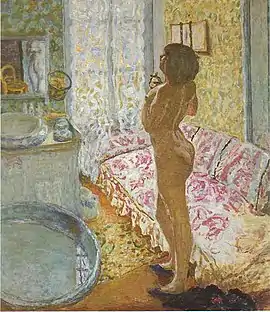

Throughout the early 20th century, as new artistic movements emerged, Bonnard kept refining and revising his personal style, and exploring new subjects and media, but keeping constant the characteristics of his work. Working in his studio at 65 rue de Douai in Paris, he presented paintings at the Salon des Independents in 1900, and also produced 109 lithographs for Parallèment, a book of poems by Paul Verlaine.[17] He also took part in an exhibition with the other Nabis at the Bernheim Jeaune gallery. He presented nine paintings at the Salon des Independents in 1901. In 1905, he produced a series of nudes and of portraits, and in 1906 had a personal exposition at the Bernheim-Jeune Gallery. In 1908, he illustrated a book of poetry by Octave Mirbeau, and made his first long stay in the South of France, at the home of the painter Manguin in Saint-Tropez. in 1909 and, in 1911, began a series of decorative panels, called Méditerranée, for the Russian art patron Ivan Morozov.[18]

During the years of the First World War, Bonnard concentrated on nudes and portraits, and in 1916 completed a series of large compositions, including La Pastorale, Méditterranée, La Paradis Terreste and Paysage de Ville. His reputation in the French art establishment was secure; in 1918 he was selected, along with Renoir, as an honorary President of the Association of Young French Artists.[18]

In the 1920s, he produced illustrations for a book by Andre Gide (1924) and another by Claude Anet (1923). He showed works at the Autumn Salon in 1923, and in 1924 was honored with a retrospective of sixty-eight of his works at the Galerie Druet. In 1925, he purchased a villa in Cannes.[18]

Siesta (1900), National Gallery of Victoria

Siesta (1900), National Gallery of Victoria La Charmille (1901)

La Charmille (1901)

Vernonnet - Paysage près de Giverny (1922), Aberdeen Art Gallery

Vernonnet - Paysage près de Giverny (1922), Aberdeen Art Gallery

Final years and death (1939–1947)

In 1938, Bonnard and Vuillard's works were featured at an exposition at the Art Institute of Chicago. The outbreak of World War II in September 1939 forced Bonnard to depart Paris for the south of France, where he remained until the end of the war. Under the German occupation, he refused to paint an official portrait of French collaborationist leader Marechal Petain, but accepted a commission to paint a religious painting of Saint Francis de Sales, with the face of his friend Vuillard, who had died two years earlier.[19]

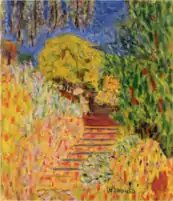

In 1947 he finished his last painting, The Almond Tree in Blossom, a week before his death in his cottage on La Route de Serra Capeou near Le Cannet, on the French Riviera. The Museum of Modern Art in New York City organized a posthumous retrospective of Bonnard's work in 1948, although originally it was meant to be a celebration of the artist's 80th birthday.

Nude in the Bath and Small Dog, (c. 1941–1946) Carnegie Museum of Art

Nude in the Bath and Small Dog, (c. 1941–1946) Carnegie Museum of Art Last self-portrait (1945) Bemberg Fondation

Last self-portrait (1945) Bemberg Fondation Stairs with Mimosa (1946)

Stairs with Mimosa (1946)

Japanism

Japanese art played an important part in Bonnard's work. He was first able to see the works of Japanese artists via the Paris gallery of Siegfried Bing. Bing brought works by Hokusai and other Japanese print makers to France, and from May 1888 through April 1891 published a monthly art journal, Le Japon Artistique, which included color illustrations in 1891. In 1890, Bing organized an important exhibition of seven hundred prints he had brought from Japan, and made a donation of Japanese art to the Louvre.[20]

Bonnard used the model of Japanese kakemono scroll art—long, vertical panels—in his series of paintings Women in the garden (1890–91), now in the Museé d'Orsay. Originally designed to appear together as a single screen, Bonnard decided to display Women in the garden as four separate decorative panels. The female forms are reduced to flat silhouettes, and there is no rendering of depth in the picture. The faces are turned away from the viewer and the pictures are entirely dominated by the colors and bold patterns of the costumes and the backgrounds. The models are his sister Andreé and his cousin Berthe Schaedin.[21] Bonnard often pictured women in checkered blouses, a design he said he had discovered in Chinese prints.[20]

Painted screen with crane, ducks, pheasant, bamboo and ferns (1889)

Painted screen with crane, ducks, pheasant, bamboo and ferns (1889) Painted screen; the Bonnard family in the garden (1896), Alte Nationalgalerie

Painted screen; the Bonnard family in the garden (1896), Alte Nationalgalerie

Graphic arts

Bonnard wrote, "Notre génération a toujours cherché les rapports de l'art avec la vie" (Our generation always was searching for connections between art and life).[22] Bonnard and the other Nabis were particularly interested in integrating their art into popular forms, such as posters, journal covers and illustrations, and engravings in books, as well as into ordinary household decoration, in the form of murals, painted screens, textiles, tapestries, furniture, glass and dishes.[23]

At the beginning of his career, Bonnard designed posters for a French champagne firm, for which he gained public attention. He later produced many sets of engravings illustrating the works of the avant-garde authors of his time.

Poster for France-Champagne by Pierre Bonnard (1891), which made him known outside the art world

Poster for France-Champagne by Pierre Bonnard (1891), which made him known outside the art world Poster for the review Blanche, Metropolitan Museum also published in Les Maîtres de l'Affiche

Poster for the review Blanche, Metropolitan Museum also published in Les Maîtres de l'Affiche Les Parisiens, lithograph (1893)

Les Parisiens, lithograph (1893) Illustration for a music textbook written by his brother-in-law, composer Claude Terrasse (1893)

Illustration for a music textbook written by his brother-in-law, composer Claude Terrasse (1893)

Method

.jpg.webp)

Bonnard is known for his intense use of color, especially via areas built with small brush marks and close values. His often complex compositions—typically of sunlit interiors and gardens populated with friends and family members—are both narrative and autobiographical. Bonnard's fondness for depicting intimate scenes of everyday life, has led to him being called an "Intimist"; his wife Marthe was an ever-present subject over the course of several decades.[24] She is seen seated at the kitchen table, with the remnants of a meal; or nude, as in a series of paintings where she reclines in the bathtub. He also painted several self-portraits, landscapes, street scenes, and many still lifes, which usually depicted flowers and fruit.

Bonnard did not paint from life but rather drew his subject—sometimes photographing it as well—and made notes on the colors. He then painted the canvas in his studio from his notes.[25] "I have all my subjects to hand," he said, "I go back and look at them. I take notes. Then I go home. And before I start painting I reflect, I dream."[26]

He worked on numerous canvases simultaneously, which he tacked onto the walls of his small studio. In this way, he could more freely determine the shape of a painting; "It would bother me if my canvases were stretched onto a frame. I never know in advance what dimensions I am going to choose."[27]

Critical reception and legacy

Claude Roger-Marx remarked that Bonnard "catches fleeting poses, steals unconscious gestures, crystallises the most transient expressions".[24]

Although Bonnard avoided public attention, his work sold well during his life. At the time of his death, his reputation had been eclipsed by subsequent avant-garde developments in the art world; reviewing a retrospective of Bonnard's work in Paris in 1947, Christian Zervos assessed the artist in terms of his relationship to Impressionism, and found him wanting. "In Bonnard's work," he wrote, "Impressionism becomes insipid and falls into decline."[28] In response, Henri Matisse wrote: "I maintain that Bonnard is a great artist for our time and, naturally, for posterity."[29]

Bonnard was described, by his own friend and historians, as a man of "quiet temperament" and one who was unobtrusively independent. His life was relatively free from "the tensions and reversals of untoward circumstance." It has been suggested that: "Like Daumier, whose life knew little serenity, Bonnard produced a work during his sixty years' activity that follows an even line of development."[30]

Bonnard has been described as "the most thoroughly idiosyncratic of all the great twentieth-century painters", and the unusual vantage points of his compositions rely less on traditional modes of pictorial structure than voluptuous color, poetic allusions and visual wit.[31] Identified as a late practitioner of Impressionism in the early 20th century, he has since been recognized for his unique use of color and his complex imagery.[27] "It's not just the colors that radiate in a Bonnard," writes Roberta Smith, "there's also the heat of mixed emotions, rubbed into smoothness, shrouded in chromatic veils and intensified by unexpected spatial conundrums and by elusive, uneasy figures."[32]

Two major exhibitions of Bonnard's work took place in 1998: February through May at the Tate Gallery in London, and from June through October at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. In 2009, the exhibition "Pierre Bonnard: The Late Interiors" was shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[31] Reviewing the exhibition for the magazine The New Republic, Jed Perl wrote:

"Bonnard is the most thoroughly idiosyncratic of all the great twentieth-century painters. What sustains him is not traditional ideas of pictorial structure and order, but rather some unique combination of visual taste, psychological insight, and poetic feeling. He also has a quality that might be characterized as perceptual wit—an instinct for what will work in a painting. Almost invariably he recognizes the precise point where his voluptuousness may be getting out of hand, where he needs to introduce an ironic note. Bonnard's wit has everything to do with the eccentric nature of his compositions. He finds it funny to sneak a figure into a corner, or have a cat staring out at the viewer. His metaphoric caprices have a comic edge, as when he turns a figure into a pattern in the wallpaper. And when he imagines a basket of fruit as a heap of emeralds and rubies and diamonds, he does so with the panache of a magician pulling a rabbit out of a hat."[31]

In 2016, the Legion of Honor in San Francisco hosted an exhibit "Pierre Bonnard: Painting Arcadia", featuring more than 70 works spanning the artist's entire career.[33]

Bonnard's record price in a public sale was for Terrasse à Vernon, sold by Christie's in 2011 for €8,485,287 (£7,014,200).[34]

In 2014, the painting La femme aux Deux Fauteuils (Woman with Two Armchairs), with an estimated value of around €600,000 (£497,000), which had been stolen in London in 1970, was discovered in Italy. The painting, together with a work by Paul Gauguin known as Fruit on a Table with a Small Dog had been bought by a Fiat employee in 1975, at a railway lost-property sale, for 45,000 lira (about £32).[35]

Bonnard features heavily in the 2005 Booker prize winning novel, The Sea by John Banville. In the novel, the protagonist and art historian Max Morden is writing a book about Bonnard and discusses the painter's life and work throughout.

Bonnard is played by Vincent Macaigne and Marthe by Cécile de France in the 2023 French film directed by Martin Provost Bonnard, Pierre and Marthe, which focuses on the couple's romance.[36] The movie premiered at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival .[37]

References and sources

References

- Encyclopædia Britannica on-line

- Grove Art Online

- Phillips Collection

- Cogebal, Guy, Bonnard, p. 8

- Cogeval, Guy, Bonnard (2015), p. 148

- Cogeval, Guy, Bonnard (2015), p. 8

- Cogeval, Guy, Bonnard (2015) p. 8

- "Pierre Bonnard | French artist". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- abcgallery.com

- ugeniodavenezia.eu

- Cogeval, Guy, Bonnard (2015) p. 148

- Serrano, V. (2019). He who sings is not always happy. In Tate Gallery exhibition catalogue, "Pierre Bonnard: The colour of memory", pp. 34–39

- Cogeval (2015), p. 9

- Cogeval (2015), p. 10

- Cited in Cogeval (2015), p. 11

- Brodskaya, 42

- Cogeval (2015), page 148

- Cogeval (2015), p. 149

- Cogenal (2015), pp. 136–137)

- Lacambre, Geneviève, La déferlante japonaise, published in Les Nabis et le décor, Beaux Arts Editions (March 2019), pp. 38–40

- Bétard, Daphne, Prophètes d;un art total, Les Nabis et le décor, Beaux Arts Editions, p. 18 (March 2019)

- Cited in Flouquet, Sophie, L'Art Nouveau, du sol au plafond p. 42, Les Nabis et le decor, Beaux Arts Éditions (2019)

- Flouquet, Sophie, L'Art Nouveau, du sol au plafond p. 42, Les Nabis et le decor, Beaux Arts Éditions (2019)

- Graham-Dixon, Andrew (24 August 2003). "ITP 175: The Open Window by Pierre Bonnard". Sunday Telegraph.

- Cowling and Mundy, 1990, p. 38.

- Art, Smith College Museum of; Davis, John; Leshko, Jaroslaw (2000). The Smith College Museum of Art: European and American Painting and Sculpture, 1760-1960. Hudson Hills. p. 28. ISBN 9781555951948.

- Amory, 4

- Brodskaya, 14

- Brodskaya, 16

- Stanton L. Catlin, "Pierre Bonnard's Dining Room in the Country," The Minneapolis Institute of Arts Bulletin 44, No. 6, November 1955, pp. 43-49

- Perl, Jed (1 April 2009). "Complicated Bliss". New Republic. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- Smith

- "Pierre Bonnard: Painting Arcadia". Legion of Honor. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- "Un tableau de Gauguin retiré des enchères à Londres". La Presse (in French). lapresse.ca. 9 February 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Davies, Lizzy (2 April 2014). "Stolen paintings hung on Italian factory worker's wall for almost 40 years". The Giuardian. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- "'Bonnard, Pierre and Marthe' Sells to Major Markets for Memento International, First Stills Unveiled (EXCLUSIVE)". 11 January 2023.

- "Cannes Premiere Title 'Bonnard, Pierre and Marthe' Sells for Memento International; Trailer Unveiled (EXCLUSIVE)". 9 June 2023.

Sources

- Amory, Dita, ed. (2009). Pierre Bonnard: The Late Still Lifes and Interiors. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14889-3

- Brodskaya, Nathalia (2011). Bonnard. Parkstone International. ISBN 1780420943

- Cogeval, Guy (2015). Bonnard. Paris: Hazan, Malakoff. ISBN 978-2-7541-08-36-2

- Cowling, Elizabeth; Mundy, Jennifer (1990). On Classic Ground: Picasso, Léger, de Chirico and the New Classicism 1910-1930. London: Tate Gallery. ISBN 1-85437-043-X

- Frèches-Thory, Claire, & Perucchi-Petry, Ursula, ed.: Die Nabis: Propheten der Moderne, Kunsthaus Zürich & Grand Palais, Paris & Prestel, Munich 1993 ISBN 3-7913-1969-8

- Hyman, Timothy (1998). Bonnard. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-20310-1

- Ives, Colta Feller; Giambruni, Helen Emery; Newman, Sasha M (1989). Pierre Bonnard: the Graphic Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-566-9.

- Smith, Roberta. Bonnard Late in Life, Searching for the Light, The New York Times, January 29, 2009

- Turner, Elizabeth Hutton (2002). Pierre Bonnard: Early and Late. London: Phillip Wilson. ISBN 978-0-85667-556-0

- Whitfield, Sarah; Elderfield, John (1998). Bonnard. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-4021-3

External links

- Pierre Bonnard at the Museum of Modern Art

- "Complicated Bliss" by Jed Perl, The New Republic, 1 April 2009

- Works by Pierre Bonnard (public domain in Canada)

- Pierre Bonnard in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website