Crossmolina

Crossmolina (Irish: Crois Mhaoilíona)[2] is a town in the Barony of Tyrawley in County Mayo, Ireland, as well as the name of the parish in which Crossmolina is situated. The town sits on the River Deel near the northern shore of Lough Conn. Crossmolina is about 9 km (5.6 mi) west of Ballina on the N59 road. Surrounding the town, there are a number of agriculturally important townlands, including Enaghbeg, Rathmore, and Tooreen.

Crossmolina

Crois Mhaoilíona | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Montage including; Top: A view of the statue at the centre of the town of Crossmolina. Centre: Deel River and Saint Mary's Church. Bottom: Street view in centre of the town | |

Crossmolina Location in Ireland | |

| Coordinates: 54°06′00″N 9°19′00″W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Connacht |

| County | County Mayo |

| Elevation | 24 m (79 ft) |

| Population | 1,044 |

| Irish Grid Reference | G137175 |

| Website | crossmolina |

Etymology

The name Crossmolina is from the Irish: Crois Uí Mhaoilíona, meaning "Cross of Mullany",[3][4] or "Maoilíona's cross".[5] In the 18th century, the name was sometimes spelt as either Crossmalina, Crossmaliney, Crosmolyna or Crossmaling.[6][7]

History

The origins of present-day Crossmolina are tied to the founding of a religious settlement in the area: Errew Abbey was founded by St. Tiernan in the 6th century.[8] In the 12th century this Abbey came into possession of the invading Hiberno-Norman de Barry family.

Anglo Protestant Ascendency

During the 15th century, Crossmolina passed into the hands of the Bourke Family. In 1526 O'Donnell of Tir Conaill (County Donegal) invaded Tirawley and destroyed Crossmolina Castle.[9] In response, the Bourkes constructed a replacement in Deel Castle.[10] Their possession of this new fortress did not last however as during the Williamite War in Ireland of the 1690s Thomas Burke fought for the defeated Catholic Jacobites.

Subsequently, Deel Castle was granted by the English crown to the Anglo-Irish Protestant Gore family. In the 17th century, Francis Jackson, who had fought with Cromwell in Ireland, also received land in North Mayo. The Jackson family later built Enniscoe House. Again, the land taken over by the Jacksons was previously owned by the Burke family.[11] The arrival of these landlords ushered in the era of Protestant Ascendancy into the area.[10]

In 1798 Crossmolina was swept up with the events of the United Irishmen Rebellion when French Forces under General Humbert came from Ballina, passed by Crossmolina, towards Lahardane and on towards Castlebar as they went west of Lough Conn to fight the Battle of Castlebar.[12]

In the late 18th century, the town became a local commercial and administrative centre. By the early 1800s, a granary and bonded warehouses were established in the town. In 1823, Petty Court sessions were held in the town on a weekly basis.[13] By the 1830s, the Revenue Police and Constabulary were stationed in the town.[14] Regular fairs were held in May, September and December.[15] The town is referenced in the Leigh's pocket road book of Ireland, published in 1827, as a "village in Mayo", whose "most remarkable object is the ruin of an Abbey dedicated to the Virgin Mary".[7] Crossmolina was also mentioned in Samuel Lewis' Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (1837). The population of the town at that time was estimated to be 1,431, who lived in 310 house The town contained "one good street and two converging ones". Lewis also enumerated the main local landlords:

'There are several gentlemen's seats in the vicinity: the principal are Eniscoe, the residence of M. Pratt, Esq.; Gurtner Abbey, of G. Ormsby, Esq.; Abbeytown, of W. Orme, Esq.; Knockglass, of T. Paget, Esq.; Fortland, of Major Jackson; Glenmore, of W. Orme, Esq.; Greenwood Park, of Capt. J. Knox; Belleville, of W. Orme, Esq.; Millbrook, of W. Orme, sen., Esq; Netley Park, of H. Knox, Esq.; Castle Hill, of Major McCormick; Ballycorroon, of E. Orme, Esq.; Stone Hall, of T. Knox, Esq.; Fahy, of Ernest A. Knox, Esq.; Cottage, of W. Ormsby, Esq.; Rappa Castle, of Annesley Gore Knox, Esq. (See Kilfyan); and the Vicarage-house, the residence of the Rev. — St. George, rector. Deel castle, on the banks of the river of the same name, now a fine modern residence, surrounded with much old timber, stands on the site of a very ancient structure."[16]

Poitin Production

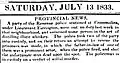

Poitín is a traditional Irish spirit made from fermented grain or potatoes and it has a high alcohol content. Poitín has been produced in Ireland for centuries, and it has played an important role in the local economy around Crossmolina. In the early 19th century, the government of Ireland was concerned about the widespread practice of private distillation. Private distillation was illegal and actively suppressed. Conflict between the authorities and the local population was relatively common. In February 1816, the extent of poitin production in North Mayo became such a grave concern to the government that troops were stationed in the town to suppress the trade.[17] In July 1833, a party of Revenue Police, based in Crossmolina, made a routine patrol and made an unexpected discovery—individuals engaged in the illicit distillation of poitín. The police apprehended two members of the group. However, as they were returning with the prisoners, a daring attempt to rescue them was made, with a prominent role played by one of the prisoners' father-in-law. Tragically, the situation escalated, leading the police to discharge their weapons, resulting in the death of one man.[18][19]

Rural unrest in the 19th century

The structure of land ownership in North Mayo was a constant source of tension throughout the 19th century. Large landowners, who often lived in England, rented land to tenant farmers. The tenant farmers' tenure on the land was often precarious, meaning that they could be evicted at any time. This led to significant resistance from the local population when rents were adjusted. The resistance sometimes led to violence. The rural areas surrounding Crossmolina suffered from endemic poverty. The Royal Commission into the Condition of the Poorer Classes in Ireland, published in 1838,provided some data on the living conditions of the rural poor living near. The diet of the poor was almost entirely potatoes. Meat was very rare, and was only eaten once or twice a year. Labourers could expect a daily payment of between 6 and 8 pennies per day. Some of their wages were paid in the form of food.[20]

During the first decade of the century, local peasants formed a secret society called "The Threshers". The group was responsible for a number of "outrages" including destroying crops and breaking into houses. The group wore a uniform of white shirts. In 1806 a local man – Thady Lavin – had informed the local magistrate of the activities of the group. He was later found murdered near Crossmolina. Six local men - Coll Flynn, Laurence Flynn, Charles Flynn, Thomas Horan, Daniel Regan, and Daniel Callaghan - were convicted of his murder, and hanged in Castlebar in December 1806.[21][22][23]

In December 1813, violence again broke out when a crowd of local residents, armed with pikes and guns, tried to take back cattle that had been sequestered to pay for outstanding rent arrears.[24]

Between 1820 and 1840, the agrarian movement - the "Ribbonmen" - were active in Crossmolina. In December 1821, four local men, John Carr, Peter Gillaspy, Eneas Early, and Mathew Chambers, were sent to prison for membership of the Ribbonmen and for administering illegal oaths.[25] The local magistrate, George Ormsby, Esq. of Gortner Abbey, was responsible for sending the men to prison. Owing to the high degree of rural unrest, in 1820 a detachment of the yeomanry consisting of three officers and 85 men was on permanent duty in the town.[26] In February 1839, the Crossmolina Parish Priest - Fr John Barrett - was murdered at Enniscoe Gate, about a mile and a half from Crossmolina. He was attacked late at night while returning from the town to his residence. It was widely speculated at the time that he was murdered because he denounced at the pulpit the activities of a secret society called the "Steel Boys".[27] In 1842, a local Crossmolina Man - John Walsh - was convicted of being a member of the Ribbonmen and transported for seven years. He was found to be in possession of secret passwords and documents relating to the secret society.[28]

Rural violence and political unrest continued through to the second half of the 19th century and even into the early 20th century. In March 1881, the Crossmolina home of the high constable of Tryrawley was attacked by a group of armed men.[29] In November 1882, the local Parish Priest was arrested for permitting a Land League meeting in the Crossmolina Chapel.[30] In June 1882, a Crossmolina farmer called Michael Brown was shot and severely wounded. He had taken over a farm that had been boycotted by local residents.[31] Violence broke out in 1911 when a local man, Patrick Broderick who along with his neighbours, resisted the efforts of over fifty R.I.C. Officers to evict Broderick from his Crossmolina home. Resistance to the eviction was organized by the Crossmolina tenants league.[32]

The Big Wind

The town was badly damaged during the "Night of the Big Wind" (Irish: Oíche na Gaoithe Móire) that swept across Ireland on 6 January 1839. Almost every house in the town was damaged with four houses destroyed completely. Eight residents were killed.[33]

Potato Crop Failures

During the first half of the nineteenth century, failures of the potato crop were a regular occurrence leading to periodic famines. In 1822, there was a widespread failure of the potato crop in North Mayo. In June of that year, the Archbishop of Tuam made a pastoral visit to the area. In a letter to the London Times, he reported that in Crossmolina and other towns of North Mayo he witnessed a "multitude of half starved men, women and children".[34] Local landlords and clergy established an inter-denominational relief committee. Richard Sharpe – an agent for the Palmer estate who owned large amounts of land around Crossmolina - was particularly active in the relief efforts. He organized shipments of oats to relieve starvation around the town.[35]

In the early months of 1831, there was another potato crop failure. Sharpe again organized a collection among local landlords to purchase a shipment of oats to feed the starving tenants.[36] In June 1831, the town suffered an outbreak of Typhus - a disease that periodically broke out in North Mayo up to the 1920s. Dr. James McNair reported to the Connaught Telegraph that he had identified over 100 cases of Typhus, of which 38 patients lived within Crossmolina.[37] Also in June 1832, the Church of Ireland minister of Crossmolina - the Rev. Edwin Stock - conducted a survey of the surrounding area to identify the extent of distress. The survey identified over 3,000 families comprising some 17,000 individuals suffering from a lack of food. One of the local landlords and secretary of the relief committee - George Vaughn Jackson - wrote a letter to the London Times, where he reported that in Crossmolina "the present distress is fearful....poor mothers wailing for their children, and hordes of men roaming about asking for work and food, carry(ing) with them the unequivocal proofs of positive starvation. Fever has been raging a good while, and will, it is feared, increase."[38]

The crop failures of 1822 and 1832 were precursors to the disastrous famine of the 1840s. By the 1840s, the countryside around Crossmolina was already plagued by destitution, leaving many in dire circumstances. The impoverished population heavily relied on the potato as their main food source. However, in August 1845, disaster struck when a devastating fungus, later identified as Phytophthora infestans, began decimating the potato crops. The once-green stalks of potato ridges quickly succumbed to blight, resulting in a putrid stench emanating from the rotting crops.[39] The Famine devastated the rural areas surrounding Crossmolina, slicing the population from 12,221 in 1841 to 7,236 by 1851.[40] It also had drastic effects on the use of language in the area: It is estimated that over 80% of the Crossmolina area spoke the Irish Language prior to the famine.[41]

By early 1847, the horrific impact of the Great Famine in Crossmolina had received widespread publicity in England. A local Protestant clergyman, Reverend St. George Knox, wrote in a letter to the London Evening Standard, where he described the distress in the town. He highlighted the increasing prices of provisions and the congregation of the poor in search of relief. He mentioned that within the last month alone, sixteen deaths occurred, and approximately 900 people in the parish were without means to procure food. Despite these dire circumstances, Reverend Knox noted the remarkable patience and peacefulness exhibited by the local population, emphasising that "no depredations were committed", even though deaths occurred daily due to starvation.[42]

Another article in the London Evening Standard, published in January 1847, described a dire situation in the town. Inquests were being held on people who died suddenly, seemingly without illness, suggesting that the cause was the diseases brought on by a lack of food. Reports indicated that scores of people were dying every day in North Mayo due to malnutrition-related illnesses, with some resorting to eating raw vegetables in desperate attempts to stave off hunger.[43]

Due to the work of the local coroner and doctor (Mr Atkinson and Dr McNair), the names of some of the famine victims were recorded in the local press. The victims often moved from their homes in the countryside to beg in the town.

- At an inquest held in the town in December 1846, local residents Michael Walsh. John Moonelly (Munnelly), Michael McGevir and Anthony Mally were found to have died from starvation.[44]

- James Fleming (aged 60) and Edward Fleming (aged 13) died of hunger in March 1847 in Corrrabeg, near Crossmolina.[45]

- Bernard Rogan died in the town in December 1846. He was part of a family from Limerick, who were denied entrance to the poor house in the city. The family became itinerant, began begging and ended up in Crossmolina where the boy died.[46]

- Michael Moran also died in December 1846. During the last six weeks of his life, he and his family had been forced to beg for food.[46]

- Matthew Temple starved to death in the town in January 1847.[47]

- At an inquest held in February 1847, the deaths of Mary Minn and Patrick Gorman - both residents of Crossmolina - were recorded as deaths due to starvation. The inquest recorded a further 16 deaths of residents in the surrounding villages as due to starvation.[48]

- In March 1847, the body of Bridget McDermott was found dead in the town. The coroner recorded a verdict of death by starvation.[49]

Land League

Like much of Mayo, the Land League was active in the town and the surrounding area, and several local members were arrested on account of the activities of the League. In March 1881, two Crossmolina members of the League, whose names were Cawley and Daly, were arrested under the provisions of the Coercion Act.[50] They were escorted to Kilmainham jail under armed guard.[51] In October 1881, the Rev. McHale - Parish Priest of Adergoole was arrested under the same Coercion Act for holding a Land League meeting in the Roman Catholic Chapel.[52] A month later, Peter Doherty, a member of the Crossmolina branch of the league was also arrested.[53]

The activities of the Crossmolina Land League were discussed in the House of Commons during the debate on the Protection of Persons and Property (Ireland) Bill in January 1881. The Bradford MP W. E. Forster claimed that armed men from the Crossmolina Land League were visiting local tenants and demanding that they refuse to make any rent payments beyond the amounts registered in the Griffith's Valuation. Forster further claimed that armed men also told the tenants that they should not buy goods from a local Crossmolina grocer called Hogan. Forster described Hogan as "a respectable grocer, (who) refuses to join the Land League or subscribe to it."[54]

Crossmolina Conspiracy

In May 1883, a number of local men were arrested in what became known as the Crossmolina Conspiracy. The arrests included Thomas Daly, Thomas Macaulay, James King, Richard Halloran, Patrick Nunelly, and Patrick Nally. The were charged with conspiracy to murder local landlords and their agents. During the search of the prisoners' houses, the police discovered two rifles, a revolver, and explosives.[55] Patrick Nally - a member of the Supreme Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood - was later tried, convicted, and sentenced to 10 years in prison.[56] He died of Typhoid in prison in November 1891.[57] One of the stands in Croke Park was named after Patrick Nally.[58]

The Crossmolina Riot

On Sunday, 28 August 1910, a riot broke out in Crossmolina when the leader of the All for Ireland League (AFIL) - William O'Brien MP - tried to hold an open-air meeting in the town centre. The league was a non-sectarian nationalist political party that briefly flourished prior to the first world war. Its main objective was to form a broad coalition between the Unionist and Nationalist populations. The league was opposed by more Catholic nationalist organisations such as the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH) and the United Irish League.

O'Brien had scheduled a meeting in the town, and fearing a conflict with the local population, he was accompanied by a large contingent of police as well as a large number of AFIL supporters. When he entered the town, he was confronted by a large group of locals armed with sticks and rocks. O'Brien planned to speak at an open-air meeting at the corner of Chapel Street. To get him to chapel street, the police baton-charged the crowd, eventually succeeding in pushing the locals back and allowing O'Brien to speak. However, the Lahardane Fife and Drum band began to play while the locals started shouting preventing O'Brien from being heard. Further violence broke out and a revolver was fired as AFIL retreated from the town towards Ballina. O'Brien was struck on the head by a stick by one of the rioters. A month later, Thomas Moclair was found guilty of discharging a firearm at the Crossmolina Petty Sessions. He was fined 10s and forced to pay court costs.[59] The event received widespread media coverage throughout the United Kingdom.[60][61]

War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence was a conflict fought between the Irish Republican Army and British forces: the British Army, the Royal Irish Constabulary. There were a number of sporadic incidents during the war that occurred in Crossmolina and the surrounding areas. A company of Irish Volunteers was established in August 1917. The seven original members of the company were the brothers Martin and Patrick Loftus, Patrick Hegarty, James O’Hara, Ned O’Boyle, Ned Murphy and John Timoney.[62]

In July 1920, Mossbrook House, a large house just outside Crossmolina was destroyed.[63] Around the same time, four Sinn Féin activists - who were all brothers from the Hegarty family of Castlehill, Crossmolina - were arrested and escorted to Castlebar under a heavy military escort.[64]

An RIC policeman – Constable William Kelly – was tried by court-martial for the attempted murder of a civilian in Crossmolina. On 20 December 1920 Constable Kelly was drunk when he confronted a local man and opened fire with his rifle. When he was arrested, he admitted to firing "at a bloody Sinn Feiner." He was found not guilty of attempted murder, but guilty of shooting with intent to do grievous bodily harm.[65]

In October 1920, John O'Reilly – a resident of Crossmolina – faced a court-martial in Galway. He was accused of possessing a revolver and threatening local R.I.C. officers. He warned the officers to resign from the police force. He also threatened to burn down the local R.I.C. barracks. Subsequently, a number of officers posted to Crossmolina resigned from the force.[66][67]

In Spring 1922, a company of the IRA based in Crossmolina was responsible for attacking and burning the R.I.C. Station in Bellacorick.[68]

In February 1922, the IRA declared "martial law" in Crossmolina. The Irish Transport and General Workers Union organized a strike in Davis Bros after an Apprentice was fired. During the strike, a warehouse owned by Davis was burnt, destroying a large number of eggs awaiting shipment. A large number of cattle were maimed, belonging to a farmer who condemned the attack on Davis Bros. Ten local men were arrested in connection with attacks on property.[69]

Irish Civil War

In September 1922, Malachy Geraghty (26) was shot and killed in the crossfire between Republicans and the Free State Army. Geraghty, a cattle dealer from Ballygar, was returning from the Crossmolina fair when he accidentally drove into a firefight in Ballina.[70] Earlier in the month, Mossbrook House - a large mansion just outside Crossmolina - was burnt by Republicans.[71] Shortly afterwards, the National Army arrested "Brig-General" Patrick Hegarty, who was the leader of the Republicans in Crossmolina.[72]

In October 1922, Republicans attacked the National Army Barracks in Crossmolina. After a five-hour gun battle, the Republicans were forced out of the town.[73] In January 1923, the Barracks were again attacked by a sniper. There were no reported casualties but several private houses in the town were pierced by bullets.[74]

On 5 January 1923, Patrick Mahon, a native of Crossmolina, was shot dead by a National Army patrol in Ballina. The patrol heard shouts of "Up Kilroy," and "Up the Bolshies". The soldiers went to investigate and apprehended Mahon, who resisted arrest. On being brought to the barracks a National Army soldier pushed Mahon in the back with his rifle and a shot went off, killing Mahon instantly. An inquest later recorded a verdict of accidental death.[75]

Two irregulars - Nicholas Corcoran and Thomas Gill - were captured by the National Army in March 1923 in Massbrook, near Crossmolina. Corcoran was discovered with a revolver, ammunition, and explosives.[76] A few days later, Jack Leonard was arrested in his home in Crossmolina.[77] Leonard was the photographer who took one of the most iconic images of the War of Independence - "the Men of the West". It is the photo of the West Mayo IRA Flying Column, taken at Derrymartin on the slopes of Nephin mountain, in June 1921. It is widely regarded as the best contemporary photograph of an IRA Active Service Unit ever taken.[78]

Second World War

On 13 March 1942, a Bristol Type 149 Blenheim IV crashed in Killeen, Crossmolina. The plane was on a training flight from the Isle of Man. The wireless failed, the crew lost their bearings and eventually, the plane ran low on fuel. The crew made an emergency landing, but overshot the chosen landing spot and went through hedges and boulders. Two crew members were seriously injured. Two of the less seriously injured crew were repatriated to Northern Ireland the following day. The two more seriously injured crew were repatriated by ambulance a week later.[79][80]

On 25 October 1942, an RAF plane on route from Newfoundland attempted an emergency landing in Pulladoohy, near Crossmolina. However. the plane landed upside down, killing the pilot. The plane a Boston Douglas light bomber with a crew of 3 came in to land in what seemed to be a flat green field, but unfortunately, the landing site was a bog. The pilot, Captain Nils Rasmussen a Norwegian was buried with military honours in Kilmurray Cemetery. The surviving crew of the aircraft were taken in hand by local members of the Local Defence Force (LDF) and later by the Irish Army. The two survivors were Sgt Peter Frank Craske (1387671) Royal Air Force and F/Sgt Frederick Michael Fuller (R/92107), Royal Canadian Air Force.[81] The two airmen were sent across the border to Northern Ireland shortly after the crash.

Crossmolina Rambler

Crossmolina Rambler, a dog from the town was the winner of the 1950 Irish Greyhound Derby. Despite not garnering any interest or even a starting bid during an earlier sale, Crossmolina Rambler claimed victory in Dublin in August 1950. The impressive achievement earned his owner, Mr. Frank Fox of Crossmolina, a substantial prize of £1,000. Clocking in at a remarkable time of 29.70 seconds, Crossmolina Rambler set a new record as the fastest-ever competitor in the race.[82]

Economic development in the 20th century

In the 1960s, the town benefitted from the construction of the Bellacorick electricity station fueled by peat. Twenty-one houses were built in Crossmolina for the station's operating staff.[83]

Floods

The River Deel and the town of Crossmolina have a notable history of flooding. In 1926, heavy rainfall in North Mayo caused severe flooding, resulting in the inundation of shops, dwellings, and roads. Sheep, potato pits, and turf stacks were swept away, while furniture and floating hens were seen in the flooded streets.[84] In September 1945, after a recent gale, the River Deel overflowed and caused severe flooding. Chapel Street was particularly affected, with floodwater reaching a depth of four feet. The flooding resulted in damage to shops in the area.[85] Flooding occurred again in February 1958. A number of children were stranded on Church Street and required a rescue effort by the Garda.[86]

Over the past few decades, the town has experienced further flood events, including occurrences in 1989, 2006, and twice in 2015. These floods caused significant damage, with three main streets in Crossmolina Town often submerged. During the most severe flood in December 2015, approximately 120 properties were affected by floodwater.[87]

In 2021, the Office of Public Works and Mayo County Council proposed a comprehensive flood management strategy. The proposed scheme focuses on the River Deel, which flows near Crossmolina. It involves the construction of a diversion channel upstream of the town, capable of accommodating a discharge capacity of 110 cubic meters per second.

The primary objective of the diversion channel is to redirect floodwaters away from Crossmolina, channeling them towards the flood plains of Lough Conn. By doing so, the scheme aims to mitigate the risk of flooding within the town. The realization of the Crossmolina Flood Relief Scheme is contingent upon the successful conclusion of the Department for Public Expenditure and Reform's consultation process and an independent review.[88]

Population

In the census of April 2011,[89] Crossmolina had a population of 1,060 consisting of 535 males and 526 females. The population of pre-school age (0-4) was 62 of primary school-going age (5-12) was 88 and of secondary school-going age (13-18) was 76. There were 198 persons aged 65 years and over. The number of persons aged 18 years or over was 844.

Sport

GAA

The local Gaelic football team is Crossmolina Deel Rovers. Founded in 1887 as Crossmolina Dr. Crokes, they became Deel Rovers in 1906.[90] The club saw major success in the early 2000s, winning the Connacht Senior Club Football Championship in 1999, 2000 and 2002, and as well as obtaining the All-Ireland Senior Club Football Championship in 2001, and were runners-up for that title in 2003.

Football

Crossmolina AFC is the town's resident football club and was founded in 1992. The club plays in the Mayo Football League system and has seen moderate success, most notably winning the Tim Hastings League 1 title in 2015.[91]

Places of Interest

St Mary's Church - Built in 1818–19 is a fine example of an early 19th century Chapel constructed by the Church of Ireland. It was erected with the financial support of the Board of First Fruits. The interior of the church has a wall monument commemorating 'General Sir James Jackson C.C.B. K.H. who "served with distinction through the Peninsular War at Waterloo and India".[92]

Lough Conn - Ireland's seventh-largest lake, situated south of the town. The Loch is renowned as a first-class brown trout and salmon fishing location. The Lough Conn Drive is a looped drive of approx 102 km around the lake.[93]

Crossmolina Castle - Located across the road from St Mary's Church at the end of Church Street. In 1526 the castle was destroyed by O'Donnell, Chief of Tirconnell.[94]

Gortnor Abbey - A large house, built by the Ormsby family in 1780. In 1916 it was converted into a convent boarding school run by the Jesus and Mary Order of nuns.[95]

Errew Abbey - A ruined 13th-century Augustinian church that sits on a tiny peninsula on the banks of Lough Conn. Local tradition suggests that the original Abbey was founded by St Tiernan, the patron saint of Crossmolina. The abbey was reduced to ruins by Cromwellian settlers.[96]

Crossmolina Methodist Meeting House - Located on Church Street, there is the ruins of a Methodist meeting house. It was built in 1854, replacing an earlier meeting house established in 1835. The building was abandoned towards the end of the 19th century.[97]

Saint Tiernan's Catholic Church - Built in 1859–60 on a cruciform plan, and extended in 1890–93. The church bell dates from 1907. The impressive gothic-style altar was built in 1892.[98]

Enniscoe House - A country house, built between 1790 and 1798, sometimes described as "the last Great House of North Mayo". The house was built for the Anglo-Irish Jackson family using stone from an old castle. In Cromwellian times the Jacksons were granted 5,000 acres of land, which had been confiscated from the Anglo-Norman de Burgos family. At the time of the French invasion of 1798, General Humbert's men stayed at the house.[99] It now serves as a hotel.

Cawley's bar - Located on Erris Street, this two-bay two-storey building was previously a bar. Built in 1838, it was originally two separate single-bay two-storey thatched houses with shopfronts on the ground floor. The building is currently disused.[100]

Culture

Crossmolina is the subject of "Rake Street", a poem by Harry Clifton.[101]

Gallery

.

Crossmolina, Royal Irish Constabulary, circa 1912

Crossmolina, Royal Irish Constabulary, circa 1912 Revenue Police raid, 1833. Warder and Dublin Weekly Mail

Revenue Police raid, 1833. Warder and Dublin Weekly Mail

Notable people

- Peadár Gardiner, GAA

- Louise Duffy, RTE radio presenter[102]

- Dr. Michael Loftus, 28th President of the GAA

- John O’Hart, an Irish historian and genealogist. He is noted for his work on ancient Irish lineage.

- Seán Lowry, GAA

- Ciarán McDonald, GAA

- John Maughan, GAA

- Michael Moyles, GAA

- James Nallen, GAA

- John Nallen, GAA[103][104]

- Marc Roberts, Musician

- Stephen Rochford, GAA

- Kevin Rowland, musician, lead singer of Dexy's Midnight Runners.[105]

- Conor Loftus, GAA

References

- "Census 2016 Sapmap Area: Settlements Crossmalina". Central Statistics Office. Archived from the original on 26 September 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "Crois Mhaoilíona/Crossmolina". Placenames Database of Ireland (logainm.ie). Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- "RTÉ Sport: GAA - McGarrity a major doubt for Mayo". RTÉ.ie. Archived from the original on 9 July 2009. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- "Griffin jumps to victory".

- Mills, A. D. (2011). A Dictionary of British Place Names. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199609086.

- Seward, Willian Wenman (1797). Topographia Hibernica, or The topography of Ireland, ancient and modern. Alexander Stewart. p. 127.

- Leigh's new pocket road-book of Ireland, on the plan of Reichard's itineraries. London, Dublin: S. Leigh (London); R. Milliken ( Dublin). 1827.

- "Crossmolina History, Co. Mayo in the West of Ireland | mayo-ireland.ie".

- "Crossmolina Castle".

- "Deel Castle".

- Meehan, Rosa (2003). The Story of Mayo. Castlebar, Mayo, Reland: Mayo County Council. p. 139. ISBN 0-95196-244-2.

- Gribayèdoff, Valerian (1890). The French invasion of Ireland in '98. New York: Charles P. Somersby.

- "Ireland - The State of the Country". The Morning Chronicle. 27 August 1823. p. 4.

- Lewis, S. (1849). A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland: Comprising the Several Counties; Cities; Boroughs; Corporate, Market, and Post Towns; Parishes; and Villages; with Historical and Statistical Descriptions: Embellished with Engravings of the Arms of the Cities, Bishoprics, Corporate Towns, and Boroughs; and of the Seals of the Several Municipal Corporations. United Kingdom: S. Lewis and Company.

- Seward, William Wenman (1797). Topographia Hibernica, or The topography of Ireland, ancient and modern. Alexander Stewart.

- Lewis, Samuel (1837). A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland.

- "Provincial Intelligence". Freemans Journal. 29 February 1816. p. 4.

- "Provincial news". Warder and Dublin Weekly Mail. 13 July 1833.

- "Irish Revenue Police | Ard-Mhúsaem na hÉireann". National Museum of Ireland (in Irish). Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- Whately, R.; Murray; Vignoles; O'Ferrall; Carlisle; Hort; Corrie; Naper; Wrightson (1836). Condition of the poorer classes in Ireland : appendix D: baronial examination on earnings of labourers, etc. British Parliamentary Publications; University of Southampton Library: UK Parliament. pp. Parliamentary Papers, Session 1836, Vol. XXXI, p.1.

- "Thrashers". Belfast Commercial Chronicle. 20 December 1806.

- "Special Commission". Belfast Newsletter. 9 January 1807.

- Browne, George Lathom (1882). Narratives of State Trials in the Nineteenth Century: From the union to the regency, 1810-1811. S. Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington. pp. 98–124.

- "Ireland". Stamford Mercury. 31 December 1813.

- "Provincial intelligence". Freemans Journal. 10 December 1821.

- Parliamentary Papers, Session 1821 Vol. XIX (1821). Return of Number of Troops or Corps of Effective Yeomanry and Volunteers in Ireland, 1820. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office (HMSO). p. 177.

- "Supposed Murder of Catholic Clergyman". Dublin Evening Post. 21 February 1839.

- "Mayo Assizes". Belfast News-Letter. 2 August 1842.

- "Agitation in Ireland". Gloucestershire chronicle. 5 March 1881.

- "The Irish Crisis". The Graphic. 5 November 1881.

- "Affairs in Ireland". South Wales daily news. 10 June 1882.

- "Crossmolina evictions, tenant sent for trial". Freemans journal. 18 May 1911.

- Carr, Peter (1957). The big wind : [the story of the legendary big wind of 1839, Ireland's greatest natural disaster]. Belfast: White Row. pp. 89. ISBN 9781870132503.

- "From the Archbishop Of Tuam". The Times (UK). 22 June 1822.

- "State of the Country". Freemans Journal. 9 May 1822.

- "The state of the Country". Connaught Telegraph. 2 March 1831.

- "Famine in Mayo". Connaught Telegraph. 15 June 1831.

- "From George Vaughn Jackson Esq, secretary to the Crossmolina Local Committee". The Times (UK). 8 June 1831.

- "An Outline History of County Mayo - Part 4 1800 to 1900 | mayo-ireland.ie". www.mayo-ireland.ie. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- "The Famine in Mayo 1845–1850" (PDF). Mayo County Library. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- Frank on Twitter: "Pre Irish famine #Gaelic / #Gaeilge language map of Island of Ireland in 1851. https://t.co/CgA96Tp4af"

- Knox, St. George (4 January 1847). "Letter to the editor". London Evening Standard.

- "The famine-death by starvation". London, Evening Standard. 8 January 1847.

- "County of Mayo - Deaths from Starvation". Londonderry Sentinel. 12 December 1847.

- "Progress of the Pestilence and Famine - Deaths from Starvation". Newry Telegraph. 6 March 1847.

- "More Starvation". Coleraine Chronicle. 2 January 1847.

- "The Famine - County Mayo". The North Wales Chronicle and Advertiser for the Principality. 19 January 1847.

- "Ireland". London Evening Standard. 26 February 1848.

- "Deaths From Starvation - Inquests". Athlone Sentinel. 5 March 1847.

- "Arrest of Land Leaguers". Aberystwith Observer. 12 March 1881. p. 4.

- "Further arrests in Ireland". South Wales Daily News. 12 March 1881. p. 3. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- "Arrests Under the Protection Act". Irish Times. 31 October 1881.

- "Affairs In Ireland - Arrests". Huddersfield Chronicle. 30 November 1881.

- Forster, W. E. (1881). Hansard's Parliamentary Debates January 6-31, 1881: Vol 25. London: Hansard. p. 1215.

- "Discovery of arms and infernal machine; Important arrests". South Wales Daily News. 17 May 1883. p. 3. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- "Pat Nally, People from Co. Mayo in the West of Ireland | mayo-ireland-ie".

- "Death of Patrick W. Nally". North Cumberland Reformer. 19 November 1891. p. 7.

- "1856 – BIRTH OF ATHLETE, PATRICK NALLY, IN BALLA, CO MAYO". Stair na hÉireann History of Ireland. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- "Revolver firing at Crossmolina". Irish Times. 22 September 1910.

- "Dublin Castle, Molly Maguires and Co". Northern Whig. 28 September 1910.

- "Nationalist Riots". Ballymena Observer. 2 September 1910.

- "Statement of John Timoney, Crossmolina". Ballina and Its Troubled Past. 27 May 1957.

- "Irish Mansion Burnt". Yorkshire Evening Post. 5 September 1922.

- "Four Brothers Arrested". Weekly Freeman's Journal. 31 July 1920.

- "Constable charged with shooting at a civilian". Freemans Journal. 16 April 1921.

- "R.I.C. men resign". Freemans Journal. 5 August 1920.

- "Courtsmartial at Galway". Western People. 16 October 1920.

- "Patrick Hegarty: Witness Statement" (PDF). Bureau of Military History. December 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- "LAWLESSNESS IN MAYO. SERIES OF OUTRAGES LEADS TO MARTIAL LAW". Weekly Freeman's Journal. 18 February 1922.

- "Shot Dead on the Roadside: Cattle Dealer's Fate During Attack on Ballina". Weekly Freeman's Journal. 23 September 1922.

- "Irish Mansion burnt". Yorkshire Evening Post. 5 September 1922.

- "Progress in Mayo: Capture of Several Important Leaders". Weekly Freeman's Journal. 16 September 1922.

- "Wholesale Robberies in County Mayo: Ambushes and other incidents". Belfast News-Letter. 20 October 1922.

- "Sniping in Crossmolina". Derry Journal. 15 January 1923.

- "Ambush near Ballina". Southern Star. 6 January 1923.

- "Two leaders captured". Irish Times. 13 March 1923.

- "County Mayo". Irish Times. 27 March 1923.

- Healey, Jack (24 September 2019). "The photographic legacy of Jack Leonard". Mayo News.

- "Foreign Aircraft landings in Ireland - WW2". December 2018.

- "British Plane down in Mayo". Irish Independent. 14 March 1942.

- "Douglas Boston BZ200, Pulladoohy, Crossmolina, Mayo". Foreign Aircraft landings in Ireland -WW2. December 2018.

- "Dog nobody would buy wins Irish greyhound derby". Daily Mirror. 14 August 1950.

- "Fortieth anniversary of the opening of Bellacorick Power Station". Friends of the Irish environment. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "BIG FLOODS IN MAYO FURNITURE AND FOWL AFLOAT". Irish Independent. 20 November 1926. p. 7.

- "Aftermath of great gale". Irish Press. 25 September 1945. p. 1.

- "Crossmolina Flooding". Western People. 1 February 1958. p. 10.

- "Crossmolina FRS - Home". www.floodinfo.ie. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- "Start to construction on Crossmolina flood relief scheme now in sight". Connaught Telegraph. 22 April 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- "Census April 2016 (Crossmolina)" (PDF). Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- "Deel Rovers GAA". Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- "Club Honours". Crossmolina AFC. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- "Saint Mary's Church (Crossmolina), Crossmolina, County May". National Inventory of Architectural Heritage. November 2018.

- "Lough Conn Drive, County Mayo in the West of Ireland | mayo-ireland.ie". www.mayo-ireland.ie. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- "Crossmolina Castle". Crossmolina Community. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- "Gortnor Abbey". Crossmolina Community. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- "Errew Abbey". Crossmolina Community. December 2018.

- "National Inventory of Architectural Heritage". Crossmolina Methodist Meeting House, Church Street, Crossmolina, County Mayo.

- "Saint Tiernan's Catholic Church". National inventory of architectural heritage.

- Kennedy, Thomas (2022). All about Mayo. Albertine Kennedy Publishing.

- "C. Cawley, Erris Street, CROSSMOLINA, Crossmolina, County Mayo". National inventory of architectural Heritage.

- Clifton, Harry (March 2009). "Rake Street". Poetry. 193 (6): 528. JSTOR 41413585.

- "The Louise Duffy Show". RTE Radio. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- "The Great Mick Loftus - HoganStand".

- "Glorious imperfection ... The end". 29 May 2012.

- "Dexys' Kevin Rowland talks to The Works Presents". RTE News. 7 October 2016.

Sources

- Lynott, J. (1980). "A Guide to History and Antiquities West of Killala Bay"