Emperor Wu of Han

Emperor Wu of Han (Chinese: 漢武帝; 156 – 29 March 87 BC), born Liu Che (劉徹) and courtesy name Tong (通), was the seventh emperor of the Han dynasty from 141 to 87 BC.[3] His reign lasted 54 years – a record not broken until the reign of the Kangxi Emperor more than 1,800 years later — and remains the record for ethnic Han emperors. His reign resulted in a vast expansion of geopolitical influence for the Chinese civilization, and the development of a strong centralized state via governmental policies, economical reorganization and promotion of a hybrid Legalist–Confucian doctrine. In the field of historical social and cultural studies, Emperor Wu is known for his religious innovations and patronage of the poetic and musical arts, including development of the Imperial Music Bureau into a prestigious entity. It was also during his reign that cultural contact with western Eurasia was greatly increased, directly and indirectly.

| Emperor Wu of Han 漢武帝 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huangdi (皇帝) | |||||||||||||||||

Emperor Wu with two attendants | |||||||||||||||||

| Emperor of the Han dynasty | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 9 March 141 – 29 March 87 BC | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Emperor Jing | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Emperor Zhao | ||||||||||||||||

| Born | Liu Che (劉徹) 156 BC Chang'an, Han dynasty | ||||||||||||||||

| Died | 29 March 87 BC (aged 69)[1][2] Chang'an, Han dynasty | ||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Mao Mausoleum (茂陵), Xianyang, Shaanxi Province | ||||||||||||||||

| Consorts | Empress Chen Empress Xiaowusi Consort Wang Lady Li Lady Gouyi at least one other wife | ||||||||||||||||

| Issue | Liu Ju (劉據), Crown Prince Wei Liu Hong (劉閎), Prince of Qi Liu Dan (劉旦), Prince of Yan Liu Xu (劉胥), Prince of Guangling Liu Bo (劉髆), Prince of Changyi Liu Fuling (劉弗陵), Emperor Zhao of Han Eldest Princess Wei Princess Zhuyi Princess Shiyi Princess Eyi Princess Yi'an Princess Shao'fang | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| House | Liu | ||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Han (Western Han) | ||||||||||||||||

| Father | Emperor Jing | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Empress Xiaojing | ||||||||||||||||

| Emperor Wu of Han | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 漢武帝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉武帝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "The Martial Emperor of Han" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 劉徹 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 刘彻 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | (personal name) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

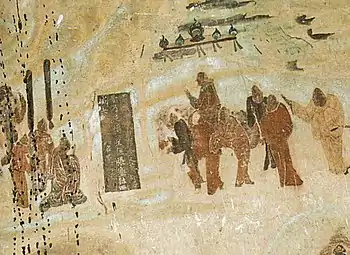

During his reign as Emperor, he led the Han dynasty through its greatest territorial expansion. At its height, the Empire's borders spanned from the Fergana Valley in the west, to northern Korea in the east, and to northern Vietnam in the south. Emperor Wu successfully repelled the nomadic Xiongnu from systematically raiding northern China, and dispatched his envoy Zhang Qian into the Western Regions in 139 BC to seek an alliance with the Greater Yuezhi and Kangju, which resulted in further diplomatic missions to Central Asia. Although historical records do not describe him as being aware of Buddhism, emphasizing rather his interest in shamanism, the cultural exchanges that occurred as a consequence of these embassies suggest that he received Buddhist statues from Central Asia, as depicted in the murals found in the Mogao Caves.

Emperor Wu is considered one of the greatest emperors in Chinese history due to his strong leadership and effective governance, which made the Han dynasty one of the most powerful nations in the world.[4] Michael Loewe called the reign of Emperor Wu the "high point" of "Modernist" (classically justified Legalist) policies, looking back to "adapt ideas from the pre-Han period."[5] His policies and most trusted advisers were Legalist,[6] favouring adherents of Shang Yang.[7] However, despite establishing an autocratic and centralised state, Emperor Wu adopted the principles of Confucianism as the state philosophy and code of ethics for his empire and started a school to teach future administrators the Confucian classics. These reforms had an enduring effect throughout the existence of imperial China and an enormous influence on neighbouring civilizations.

Names and dates

The personal name of Emperor Wu was Liu Che (劉徹).[8] The use of "Han" (漢) in referring to emperor Wu is a reference to the Han dynasty of which he was a part. His family name is "Liu"; the ruling family or clan of the Han dynasty shared the family name of "Liu", the family name of Liu Bang, the founding father of the Han dynasty. The character "Di" (帝) is a title: this is the Chinese word which in imperial history of China means "emperor". The character "Wu" (武) literally means "martial" or "warlike", but is also related to the concept of a particular divinity in the historical Chinese religious pantheon existing at that time. Combined, "Wu" plus "di" makes the name "Wudi", the emperor's posthumous name[8] used for historical and religious purposes, such as offering him posthumous honours at his tomb. The emperor's temple tablet name is Shizong (世宗)

Regnal years

One of Han Wudi's innovations was the practice of changing reign names after a number of years, as deemed auspicious or to commemorate some event. Thus, the practice for dating years during the reign of Wudi was represented by the nth year of the [Reign Year Name] (where nth stands for an ordinal integer) and "Reign Year Name" for the specific name of that regnal year.[9] This practice was continued by later emperors until the Ming and Qing eras, whereby the emperors of the two dynasties used only one reign name for their entire reign (unless interrupted, as in the case of Emperor Yingzong of Ming).

Calendar reform

In 104 BCE (1st year of the Tai'chu (太初) era), a new calendar was put into effect: the Tai'chu calendar (太初历). This calendar came about due to the observations of three officials (Gongsun Qing (公孙卿), Hu Sui (壶遂) and Sima Qian (author of Shiji) that the calendar then in use was in need of reform. Among other reforms, the Taichu calendar made the zheng month (正月, also known as the first month) the beginning of a new year, rather than the tenth month in the Zhuanxu calendar.[10] From then on, the Chinese calendar had retained the property of having the first month as the beginning of the year.

Early years

Liu Che was the 11th son of Liu Qi, the oldest living son from Emperor Wen of Han. His mother Wang Zhi (王娡) was initially married to a commoner named Jin Wangsun (金王孫) and had a daughter from that marriage. However, her mother Zang Er (臧儿) (a granddaughter of the one-time Prince of Yan, Zang Tu, under Emperor Gao) was told by a soothsayer that both Wang Zhi and her younger sister would one day become extremely honoured. She then got the idea to offer her daughters to the then crown prince Liu Qi, and forcibly divorced Wang Zhi from her husband at the time. After being offered to Liu Qi, Wang Zhi bore him three daughters – Princess Yangxin, Princess Nangong (南宫公主), and Princess Longlü.

On the day of Liu Qi's accession to the throne as Emperor Jing of Han (upon the death of his father Emperor Wen in 156 BC), Wang Zhi gave birth to Liu Che and was promoted to a consort for giving birth to a royal prince. While she was pregnant, she claimed that she dreamed of a sun falling into her womb. Emperor Jing was ecstatic over the divine implication, and made the young Liu Che the Prince of Jiaodong (胶东王) on 16 May 153 BC.[11] An intelligent boy, Liu Che was considered to be Emperor Jing's favourite son from a very young age.

Crown prince

Emperor Jing's formal wife, Empress Bo, was childless. As a result, Emperor Jing's oldest son Liu Rong, born to Lady Lì (栗姬, Emperor Jing's favorite concubine and mother of three of his first four sons), was made crown prince in 153 BC. Lady Li, feeling certain that her son would become the future emperor, grew arrogant and intolerant, and frequently threw tantrums at Emperor Jing out of jealousy over him bedding other women. Her lack of tact provided the opportunity for Consort Wang and the young Liu Che to gain the emperor's favour.

When Emperor Jing's older sister, Eldest Princess Guantao (馆陶长公主) Liu Piao (刘嫖), offered to marry her daughter with the Marquess of Tangyi Chen Wu to Liu Rong, Lady Li rudely rejected the proposal out of her dislike of Princess Guantao, who often procured new concubines for Emperor Jing and was diffusing the favor received by Lady Li. Insulted by the rejection, Princess Guantao then approached the next favorite of Emperor Jing's concubines – none other than Consort Wang, who had been observing these developments quietly from the sidelines. Guantao offered to marry her daughter to the consort's young son, Liu Che, then aged only 5. Seizing the opportunity, Consort Wang accepted the offer with open arms, securing a crucial political alliance with Princess Guantao.

Princess Guantao's daughter Chen Jiao, also known by the milk name A'Jiao (阿嬌), was of marriageable age (which was legally marked at the time by menarche), making her at least eight years older than the young prince. Due to this age difference, Emperor Jing initially did not approve of this union. According to the Wei-Jin era fable Hanwu Stories (漢武故事 / 汉武故事 also called Stories of Han Wudi), during a subsequent royal gathering, Princess Guantao held the 5-year-old Liu Che in her arms and asked the nephew whether he wanted to marry his first cousin A'Jiao. The young prince boasted that he would "build a golden house for her" if they were married. Princess Guantao then used the boy's response as a divine sign to convince Emperor Jing to finally agree to the arranged marriage between Liu Che and Chen Jiao.[12] This inspired the Chinese idiom "putting Jiao in a golden house" (金屋藏嬌).

Now sealed in the marriage alliance with Consort Wang, Princess Guantao began incessantly criticising Lady Li in front of Emperor Jing. Over time, Emperor Jing started to believe his sister's words, so he decided to test out Lady Li. One day he asked Lady Li whether she would happily foster-care the rest of his children if he were to pass away, only to have her rudely refuse to comply. This made Emperor Jing angry and worried that if Liu Rong were to inherit the throne and Lady Li to become empress dowager, many of his concubines might suffer the tragic fate of Consort Qi in the hands of Empress Lü. Princess Guantao then began to openly praise her son-in-law-to-be to her royal brother, further convincing Emperor Jing that Liu Che was a far better choice for heir apparent than Liu Rong.

Taking advantage of the situation, Consort Wang put in place the final step to defeat Lady Li — she persuaded a minister to officially advise Emperor Jing that he make Lady Li empress, as Liu Rong was already the crown prince. Emperor Jing, already firm in his view that Lady Li must not be made empress, was enraged and believed that Lady Li had conspired with government officials. He executed the clan of the minister who had made that proposal, and deposed Liu Rong from the crown prince to the Prince of Linjiang (臨江王) and exiling him from the capital city Chang'an in 150 BC. Lady Li was stripped of her titles and placed under house arrest; she died of depression not long after. Liu Rong was arrested two years later for illegal seizure of imperial shrine lands and committed suicide while in custody.

As Empress Bo had been deposed one year earlier in 151 BC, the position of empress was left open and Emperor Jing made Consort Wang empress four months later. The seven-year-old Liu Che, now legally the oldest son of the Empress, was made crown prince in 149 BC.

In 141 BC, Emperor Jing died and Crown Prince Liu Che ascended to the throne as Emperor Wu at the age of 15. His grandmother Empress Dowager Dou became the grand empress dowager, and his mother became Empress Dowager Wang. His cousin-wife A'Jiao from the political child marriage officially became Empress Chen.

Early reign and reform attempt

The Han dynasty up to this point was run according to a Taoist wu wei ideology, championing economic freedom and government decentralization. With regard to foreign policy-wise, periodic heqin was used to maintain a de jure "peace" with the powerful Xiongnu confederacy to the north. These policies were important in stimulating economic recovery following the post-Qin dynasty civil war, but had their drawbacks. The non-interventionist policies resulted in loss of monetary regulation and political control by the central government, allowing the feudal vassal states to become powerful and unruly, culminating in the Rebellion of the Seven States during Emperor Jing's reign. Nepotism among the ruling class also stagnated social mobility and encouraged nobles' rampant disregard of laws, leading to the rise of local despots who bullied and oppressed the population. The heqin policy also failed to protect the Han borders against nomadic raids, with Xiongnu cavalries invading as close as 300 li (100 miles, 160 km) from the capital during Emperor Wen's reign, and over 10,000 border residents abducted or enslaved during Emperor Jing's reign. Prominent politicians like Jia Yi and Chao Cuo had both previously advised on the necessity of important policy reforms, but neither Emperor Wen nor Emperor Jing was willing to risk implementing such changes.

Unlike the emperors before him, the young and vigorous Emperor Wu was unwilling to put up with the status quo. Only a year into his reign in late 141 BC, Emperor Wu took the advice of Confucian scholars and launched an ambitious reform, known in history as the Jianyuan Reforms (建元新政). The reforms included:

- Officially endorsing Confucianism as the national philosophy (乡儒术). Previously, the more libertarian Taoist ideals were held in esteem;

- Forcing noblemen back to their own fiefdoms (令列侯就国). A large number of noblemen were living in the capital Chang'an, lobbying court officials while exploiting the central government's budget to cover their expenses despite already having gained great wealth from their own feudal land tenure taxation. Emperor Wu's new policy dictated that they could no longer live off the government's spending and must leave the capital if lacking any justifiable reason to keep staying;

- Removing checkpoints that were not sanctioned by the central government (除关). Many lords of vassal states had established checkpoints along main state roads that went through their territory with the purpose of collecting tolls and restricting traffic. Emperor Wu wanted to seize the control of transportation from local authorities and return that control back to the central government;

- Encouraging the reporting and prosecution of criminal activities by nobles (举谪宗室无行者). Noblemen engaged in illegal activities would be impeached and punished and their assets or lands could be confiscated back as state property;

- Recruiting and promoting talented commoners in government positions (招贤良) in order to reduce the administrative monopoly by the noble class.

However, Emperor Wu's reforms threatened the interests of the nobles and were swiftly defeated by his powerful grandmother Grand Empress Dowager Dou, who held real political power in the Han court and supported the conservative factions. Most of the reformists were punished: Emperor Wu's two noble supporters Dou Ying (窦婴) and Tian Fen (田蚡, Empress Dowager Wang's half-brother and Emperor's uncle) lost their positions, and his two mentors Wang Zang (王臧) and Zhao Wan (赵绾) were impeached, arrested and forced to commit suicide in prison.

Emperor Wu, deprived of any allies, was now the subject of conspiracies designed to have him removed from the throne. For example, his first wife Empress Chen Jiao was unable to become pregnant. In an attempt to remain his first love, she had prohibited him from having other concubines. Emperor Wu's political enemies used his childlessness as an argument to seek to depose him, as the inability of an emperor to propagate a royal bloodline was a serious matter. These enemies of Emperor Wu wished to replace him with his uncle Liu An, the King of Huainan, who was renowned for his expertise in Taoist ideology. Even Emperor Wu's own maternal uncle Tian Fen switched camps and sought Liu An's favor, as he predicted the young emperor would not be in power for long. Emperor Wu's political survival now relied heavily on the lobbying of his influential aunt / mother-in-law, Princess Guantao (Liu Piao), who served as a mediator in seeking the Emperor's reconciliation with his powerful grandmother. Princess Guantao took every opportunity to influence the Grand Empress and also constantly made demands on behalf of her nephew / son-in-law.

Emperor Wu, already unhappy with his lack of an heir and Empress Chen's spoiled behavior, was further enraged by her mother Princess Liu Piao's greed, that she took a lot from him in everything she did for him. However, Emperor Wu's mother, Empress Dowager Wang, convinced him to tolerate Empress Chen and Liu Piao for the time being, as his aging grandmother was declining physically and would soon die. He spent the next few years pretending to have given up any political ambition, playing the part of a docile hedonist, often sneaking out of the capital Chang'an to engage in hunting and sightseeing and posing as an ordinary nobleman.

Solidifying power

Knowing that the conservative noble classes occupied every level of the Han court, Emperor Wu changed his strategy. He secretly recruited a circle of young loyal supporters from ordinary backgrounds and promoted them to middle-level positions in order to infiltrate executive ranks in the government. These newly established officials, known as the "insider court" (内朝), took orders and reported directly to Emperor Wu. They had real influence over the operation of government affairs though lower in rank. They became a powerful counter against the "outsider court" (外朝) made up of the Three Lords and Nine Ministers that, at the time, were mostly composed of anti-reformists. Furthermore, Emperor Wu sent out nationwide edicts appealing to grassroots scholars such as Gongsun Hong to enrol in government services in an attempt to break the stranglehold that the older-generation noble class had on the nation's levers of power.

In 138 BC, the southern autonomous state of Minyue (in modern-day Fujian) invaded the weaker neighbouring state of Dong'ou (in modern-day Zhejiang). After their king Zuo Zhenfu (驺贞复) died on the battlefield, the battered Dong'ou desperately sought help from the Han court. After a heated court debate over whether to offer military intervention for such a distant vassal state, Emperor Wu dispatched a newly promoted official Yan Zhu (严助) to Kuaiji (then still located in Suzhou, rather than Shaoxing) to mobilize the local garrison. However the tiger tally, which was needed to authorize any use of armed forces, was in Grand Empress Dowager Dou's possession at the time. Yan Zhu, as the appointed imperial ambassador, circumvented this problem by executing a local army commander who refused to obey any order without seeing the tiger tally and coerced the governor of Kuaiji to mobilize a large naval fleet to Dong'ou's rescue. Seeing that superior Han forces were on the way, Minyue forces became fearful and retreated. This was a huge political victory for Emperor Wu and set the precedent of using the Emperor's decrees to bypass the tiger tally, removing the need for cooperation from his grandmother; Of course, this did not mean that Grand Empress Dowager Dou's influence and intervention would disappear, she was a serious and insurmountable obstacle and competing authority in administration for Emperor Wu until the end of her life. But now with the military firmly in his control, Emperor Wu's political survival was assured, and his grandmother or anyone else could no longer threaten to dethrone him as directly, easily and quickly as before.

In the same year, Emperor Wu's newly favoured concubine Wei Zifu became pregnant with his first child, effectively clearing his name and silencing any political enemies who had schemed to use his alleged infertility as an excuse to have him removed. When this news reached the state of Huainan, Liu An, who was hoping the young Emperor Wu's infertility would allow him to ascend to the throne, went into a state of denial and rewarded anyone who told him that Emperor Wu was still childless.

In 135 BC, Grand Empress Dowager Dou died, removing the last major obstacle against Emperor Wu's ambition for reform.

.png.webp)

Imperial expansion

Conquest of the south

After the death of Grand Empress Dowager Dou in 135 BC, Emperor Wu had full and unrivaled control of the government. While his mother, Empress Dowager Wang, and his uncle Tian Fen were still heavily influential, they also benefited from the death of the old woman, especially the mother of Emperor Wu, but they lacked the ability to restrain the Emperor's actions.

Emperor Wu began military campaigns focused on territorial expansion. This decision nearly destroyed his empire in its early stages. Reacting to border incursions by sending out the troops, Emperor Wu sent his armies in all directions but the sea.[9]

Conquest of Minyue

Following the successful manoeuvre against Minyue in 138 BC, Emperor Wu resettled the people of Dang'an into the region between the Yangtze and Huai Rivers. In 135 BC, Minyue saw an opportunity to take advantage of the new and inexperienced king of Nanyue, Zhao Mo. Minyue invaded its south-western neighbour and Zhao Mo sought help from the Han court.

Emperor Wu dispatched an amphibious expedition force led by Wang Hui (王恢) and Han Anguo (韩安国) to address the Minyue threat. Again fearing the Han intervention, Luo Yushan (雒余善), the younger brother of Minyue's King Ying, orchestrated a coup with other Minyue nobles, killed his brother with a spear, decapitated the corpse and sent the severed head to Wang. Following the campaign, Minyue was split into a dual monarchy: Minyue was controlled by a Han proxy ruler, Zou Chou (驺丑), and Dongyue (东越) was ruled by Luo Yushan.

As Han troops returned from the Han–Nanyue War in 111 BC, the Han government debated military action against Dongyue. Dongyue, under King Lou Yushan, had agreed to assist the Han campaign against Nanyue, but the Dongyue army never reached there, blaming the weather while secretly relaying intelligence to Nanyue. Against the advice of General Yang Pu (杨仆), Emperor Wu rejected a military solution, and the Han forces arrived home without attacking Dongyue, though border garrisons were told to prepare for any military conflicts. After King Yushan was informed of this, he became overly confident and proud and responded by revolting against the Han, proclaiming himself emperor and assigned his "Han-devouring generals" (吞汉将军) to invade neighbouring regions controlled by the Han. Enraged, Emperor Wu sent a combined army led by generals Han Yue (韩说), Yang Pu, Wang Wenshu (王温舒) and two marquesses of Yue ancestry. The Han army crushed the rebellion, and the Dongyue kingdom began to fragment after King Yushan stubbornly refused to surrender. Elements of the Dongyue army defected and turned against their ruler. Eventually, the king of the other Minyue state, Zou Jugu (驺居股), conspired with other Dongyue nobles to kill King Yushan before surrendering to the Han forces. The two states of Minyue and Dongyue were then completely annexed under the Han rule.

Conquest of Nanyue

In 135 BC, when Minyue attacked Nanyue, Nanyue also sought assistance from Han even though it probably had enough strength to defend itself. Emperor Wu was greatly pleased by this gesture, and he dispatched an expedition force to attack Minyue, over the objection of one of his key advisors, Liu An, a royal relative and the Prince of Huainan. Minyue nobles, fearful of the massive Chinese force, assassinated their king Luo Ying (骆郢) and sought peace. Emperor Wu then imposed a dual-monarchy system on Minyue by creating kings out of Luo Ying's brother Luo Yushan (雒余善) and nobleman Zou Chou (驺丑), thus ensuring internal discord in Minyue .

Although initially launched as a punitive expedition by Emperor Wu against the autonomous kingdom of Nanyue, the entire Nanyue territory (which includes modern Guangdong, Guanxi, and North Vietnam) had been conquered by the Emperor's military forces and annexed into the Han Empire by 111 BC.

War against the northern steppes

Military tension had long existed between China and the northern "barbarians", mainly because the fertile lands of the prosperous agricultural civilization presented attractive targets for the poorer but more militaristic horseback nomads. The threat posed to the Xiongnu by the northward expansion of the Qin Empire ultimately led to the consolidation of the many tribes into a confederacy.[13] Following the end of the Chu-Han Contention, Emperor Gao of Han realized that the nation was not yet strong enough to confront the Xiongnu. He therefore resorted to the so-called "marriage alliance", or heqin, in order to ease hostility and buy time for the nation to "rest and recover" (休养生息). Despite the periodic humiliation of appeasement and providing gifts, the Han borders were still frequented by Xiongnu raids for the next seven decades. Following the death of his powerful grandmother, Emperor Wu decided that Han China had sufficiently recovered enough to support a full-scale war.

He first ended the official policy of peace with the Battle of Mayi in 133 BC, which involved a failed plan to trick a force of 30,000 Xiongnu into an ambush of 300,000 Han soldiers. While neither side suffered any casualties, the Xiongnu retaliated by increasing their border attacks, leading many in the Han court to abandon the hope for peace with the Xiongnu.

The failure of the Mayi operation prompted Emperor Wu to switch the Han army's doctrine from the traditionally more defensive chariot–infantry warfare to a highly mobile and offensive cavalry-against-cavalry warfare. At the same time, he expanded and trained officers from his royal guards.

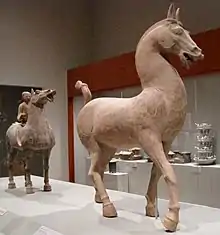

After a series of defeats by Wei Qing (the half-brother of Emperor Wu's favourite concubine) and Wei's nephew, Huo Qubing between 127 and 119 BC, the Xiongnu were expelled from the Ordos Desert and Qilian Mountains.[14] As a result of these territorial acquisitions, the Han dynasty successfully opened up the Northern Silk Road, allowing direct access to trade with Central Asia. This also provided a new supply of high-quality horse breeds from Central Asia, including the famed Ferghana horse (ancestors of the modern Akhal-Teke), further strengthening the Han army. Emperor Wu then reinforced this strategic asset by establishing five commanderies and constructing a length of fortified wall along the border of the Hexi Corridor, colonizing the area with 700,000 Chinese soldier-settlers.[15]

The Battle of Mobei (119 BC) saw Han forces invade the northern regions of the Gobi Desert.[16] The two generals led the campaign to the Khangai Mountains where they forced the Chanyu to flee north of the Gobi Desert,[17] and then out of the Gobi Desert.[18]

The Xiongnu, destabilized and worried about further Han attacks, retreated further north into the Siberian regions where they suffered starvation due to livestock loss from harsh climates. The battle was however also costly for the Han forces, which lost almost 80% of their warhorses. The cost of the war led the central Han government to introduce new levies, increasing the burden on average peasants, and the population census of the empire showed a significant drop from famines and people fleeing to avoid having to pay the taxes.

Invasion of the Korean Peninsula

Emperor Wu carried out an invasion of the northern Korean Peninsula and established the Commandery of Canghai, but abandoned it in 126 BC. Some of the military colonies established at that time survived into the 4th century, leaving behind various particularly well-preserved funerary artefacts.[9] After the conquest of Nanyue in 111 BC, Emperor Wu launched a second invasion of the Korean peninsula and by 108 BC completed the Han conquest of Gojoseon in what is now present-day North Korea and Manchuria.[19] Han Chinese colonists in the Xuantu and Lelang commanderies of northern Korea would later fight against frequent raids by the Goguryeo and Buyeo kingdoms. However, they would engage in mostly peaceful trade relations with surrounding Korean peoples over the centuries, the latter of whom became gradually and significantly influenced by Chinese culture.[20]

Diplomacy and exploration

The exploration into Xiyu was first started in 139 BC, when Emperor Wu commissioned Zhang Qian to seek out the Kingdom of Yuezhi, which had been expelled by Xiongnu from the modern Gansu region. Zhang was to entice the kingdom to return to its ancestral lands with promises of Han military assistance, with the intention that Yuezhi forces would fight against the Xiongnu. Zhang was immediately captured by Xiongnu once he ventured into the desert, but was able to escape around 129 BC and eventually made it to Yuezhi, which by then had relocated to Samarkand. While Yuezhi refused to return, it and several other kingdoms in the area, including Dayuan (Kokand) and Kangju, established diplomatic relations with Han. Zhang was able to deliver his report to Emperor Wu when he arrived back in the capital Chang'an in 126 BC after a second and shorter captivity by Xiongnu. After the Prince of Hunxie surrendered the Gansu region, the path to Xiyu became clear and regular embassies between Han and the Xiyu kingdoms commenced.

Another expansion plan, this one aimed at the south-west, was aimed at the eventual conquest of Nanyue, which was viewed as an unreliable vassal. The plan was to first obtain submission of the south-western tribal kingdoms—the largest of which was Yelang (modern Zunyi, Guizhou)—so that a route for a potential back-stabbing attack on Nanyue could be made. The Han ambassador Tang Meng (唐蒙) was able to secure the submission of these tribal kingdoms by giving their kings gifts; Emperor Wu established the Commandery of Jianwei (犍为, headquarters in modern Yibin, Sichuan) to govern over the tribes, but eventually abandoned it after being unable to cope with local revolts. Later, after Zhang Qian returned from the western region, part of his report indicated that embassies could more easily reach Shendu (India) and Anxi (Parthia) by going through the south-western kingdoms. Encouraged by the report, Emperor Wu sent ambassadors in 122 BC to try to persuade Yelang and Dian (modern eastern Yunnan) into submission again.

Religion

Han Gaozu, founder of the Han dynasty, had installed shaman cultists from the area of the former state of Jin (in the area of the modern province of Shanxi) as official religious functionaries of his new empire.[21] Emperor Wu worshiped the divinity Tai Yi (or, Dong Huang Tai Yi),[22] a deity to whom he was introduced by his shaman advisers, who were able to provide him with the experience of having this god (and other spiritual entities, such as the Master of Fate, Si Ming) summoned into his presence;[23] the emperor even went so far as to construct a "House of Life" (shou gong) chapel at his Ganquan palace complex (in modern Xianyang, Shaanxi) specifically for this purpose, in 118 BC.[24] One of the religious rituals that Emperor Wu organized was the Suburban Sacrifice,[22] and the nineteen hymns entitled Hymns for Use in the Suburban Sacrifice were written in connection with these religious rites and published during Wu's reign.[25]

It was also during this time that Emperor Wu began to show a fascination with immortality. He began to associate with magicians who claimed to be able to, if they could find the proper ingredients, create divine pills that would confer immortality. However, he himself punished others' use of magic severely. In 130 BC, for example, when the witch Chu Fu tried to approach Empress Chen to teach her sorcery and love spells to curse Consort Wei and regain Emperor Wu's affections, he dispatched Zhang Tang to execute Chu Fu for witchcraft, which was illegal at the time.

Despotism at home

Around the same time, perhaps as a sign of what would come to be, Emperor Wu began to trust governing officials who were harsh in their punishment, believing that such harshness would be the most effective method to maintain social order and so placing these officials in power. For example, one such official, Yi Zong (义纵), became the governor of the Commandery of Dingxiang (part of modern Hohhot, Inner Mongolia) and executed 200 prisoners, even though they had not committed capital crimes; he then executed their friends who happened to have been visiting. In 122 BC, Liu An, the Prince of Huainan (a previously trusted adviser of Emperor Wu, and closely enough related to have imperial pretensions) and his brother Liu Ci (刘赐), the Prince of Hengshan, were accused of plotting treason. They committed suicide; their families and many alleged co-conspirators were executed. Similar action was taken against the other vassal Princes, and by the end of the reign, all the vassal kingdoms had been political and militarily disabled.[26]

A famous wrongful execution happened in 117 BC, when the minister of agriculture Yan Yi (颜异), was falsely accused of committing a crime, though he was actually targeted because he had previously offended the emperor by opposing a plan to effectively extort double tributes out of princes and marquesses. Yan was executed for "internal defamation" of the emperor, and this caused the officials to be fearful and willing to flatter the emperor.

Further territorial expansion, old age, and paranoia

Starting about 113 BC, Emperor Wu began to display further signs of abusing his power. He began to incessantly tour the commanderies, initially nearby Chang'an, but later extending to much farther places, worshipping the various gods on the way, perhaps again in search of immortality. He also had a succession of magicians whom he honoured with great things. In one case, he even made one a marquess and married his daughter, the Eldest Princess Wei, to him; that magician, Luan Da, was later exposed as a fraud and executed. Emperor Wu's expenditures on these tours and magical adventures put a great strain on the national treasury and caused difficulties on the locales that he visited, twice causing the governors of commanderies to commit suicide after they were unable to supply the emperor's entire train.

In 112 BC, a crisis in the Kingdom of Nanyue (modern Guangdong, Guangxi, and northern Vietnam) erupted, leading to military intervention. At that time, the King Zhao Xing and his mother Queen Dowager Jiu (樛太后) – a Chinese woman whom Zhao Xing's father Zhao Yingqi had married while he served as an ambassador to Han – were both in favor of becoming incorporated into Han. This was opposed by the senior prime minister, Lü Jia (吕嘉), who wanted to maintain the kingdom's independence. Queen Dowager Jiu tried to goad the Chinese ambassadors into killing Lü, but the Chinese ambassadors were hesitant to do so. When Emperor Wu sent a 2,000-man force led by Han Qianqiu (韩千秋) and Queen Dowager Jiu's brother Jiu Le (樛乐) to try to assist the king and the queen dowager, Lü staged a coup d'état and had the king and the queen dowager killed. Lü then made another son of Zhao Yingqi, Zhao Jiande, king and went on to annihilate the Han forces under Han and Jiu. Several months later, Emperor Wu commissioned a five-pronged attack against Nanyue. In 111 BC, the Han forces captured the Nanyue capital Panyu (番禺, modern Guangzhou ) and annexed the entire Nanyue territory into Han, establishing ten commanderies.

That same year, one of the co-kings of Minyue (modern Fujian), Luo Yushan, was fearful that Han would attack his kingdom next and made a pre-emptive attack against Han, capturing a number of towns in former Nanyue and in the other border commanderies. In 110 BC, under Han military pressure, Luo Yushan's co-king Luo Jugu (骆居古) assassinated him and surrendered the kingdom to Han. However, Emperor Wu did not establish commanderies in Minyue's former territory; instead, he moved its people to the region between the Yangtze and Huai Rivers.

Later that year, Emperor Wu, at great expense, carried out the ancient ceremony of the Feng and Shan sacrifices fengshan (封禅) at Mount Tai; this involved the worship of heaven and earth and presumably a secret petition to the gods of heaven and earth to seek immortality. He then decreed that he would return to Mount Tai every five years to repeat the ceremony, but only did so once in 98 BC. Many palaces were built for him and the princes to accommodate the anticipated cycles of the ceremony.

It was around this time that, in reaction to the large expenditures by Emperor Wu that had exhausted the national treasury, his agricultural minister Sang Hongyang conceived of a plan that many dynasties would repeat later: creating national monopolies for salt and iron. The national treasury would further purchase other consumer goods when the prices were low and sell them when the prices were high at profit, thus replenishing the treasury while at the same time making sure the price fluctuation would not be too great.

In 109 BC, Emperor Wu started yet another territorial expansion campaign. Nearly a century earlier, a Chinese General named Wiman had taken the throne of Gojoseon and had established Wiman Joseon at Wanggeom-seong, (modern Pyongyang), which became a nominal Han vassal. When Wiman's grandson King Ugeo refused to permit Jin's ambassadors to reach China through his territories, Emperor Wei sent an ambassador She He (涉何) to Wanggeom to negotiate a right of passage with King Ugeo, but King Ugeo refused and had a general escort She back to Han territory. When they got close to Han borders, She assassinated the general and claimed to Emperor Wu that he had defeated Joseon in battle. Emperor Wu, unaware of his deception, made him the military commander of the Commandery of Liaodong (modern central Liaoning). King Ugeo, offended, made a raid on Liaodong and killed She. In response, Emperor Wu commissioned a two-pronged attack (one by land and one by sea) against Joseon. Initially, Joseon offered to become a vassal, but peace negotiations broke down by the Chinese forces' refusal to let a Joseon force escort its crown prince to Chang'an to pay tribute to Emperor Wu. Han took over the Joseon lands in 108 BC and established four commanderies.

Also in 109 BC, Emperor Wu sent an expeditionary force against the Kingdom of Dian (modern eastern Yunnan), planning on conquering it. When the King of Dian surrendered, it was incorporated into Han territory with the King of Dian being permitted to keep his traditional authority and title. Emperor Wu established five commanderies over Dian and the other nearby kingdoms.

In 108 BC, Emperor Wu sent general Zhao Ponu (赵破奴) on a campaign to Xiyu, and he forced the Kingdoms of Loulan on northeast border of the Taklamakan Desert and Cheshi (modern Turpan region, Xinjiang) into submission. In 105 BC, Emperor Wu gave a princess from a remote collateral imperial line to Kunmo (昆莫), the King of Wusun (Issyk Kol basin) in marriage, and she later married his grandson and successor Qinqu (芩娶), creating a strong and stable alliance between Han and Wusun. The various Xiyu kingdoms also strengthened their relationships with Han. An infamous Han war against the nearby Kingdom of Dayuan (Kokand) erupted in 104 BC. Dayuan refused to give in to Emperor Wu's commands to surrender its best horses, Emperor Wu's ambassadors were then executed when they insulted the King of Dayuan after his refusal. Emperor Wu commissioned Li Guangli, the brother of concubine Lady Li, as a general to direct the war against Dayuan. In 103 BC, Li Guangli's army of 26,000 men (20,000 Chinese & 6,000 steppe cavalry),[27] without adequate supplies, suffered a humiliating loss against Dayuan, but in 102 BC, Li with a new army of 60,000 men,[28] was able to put a devastating siege on its capital by cutting off water supplies to the city, forcing Dayuan's surrender 3,000 of its prized horses.[28] This Han victory further intimidated the Xiyu kingdoms into submission.

Emperor Wu also made attempts to try to intimidate Xiongnu into submission, but even though peace negotiations were ongoing, Xiongnu never actually submitted to becoming a Han vassal during Emperor Wu's reign. In 103 BC, Chanyu Er surrounded Zhao Ponu and captured his entire army – the first major Xiongnu victory since Wei Qing and Huo Qubing nearly captured the chanyu in 119 BC. Following Han's victory over Dayuan in 102 BC, however, Xiongnu became concerned that Han could then concentrate against it, and made peace overtures. Peace negotiations failed when the Han deputy ambassador Zhang Sheng (张胜) was discovered to have conspired to assassinate Chanyu Qiedihou (且鞮侯). The ambassador, the later-famed Su Wu, would be detained for two decades. In 99 BC, Emperor Wu commissioned another expedition force aimed at crushing Xiongnu, but both prongs of the expedition force failed. Li Guangli's force became trapped but was able to free itself and withdraw, while Li Ling, Li Guang's grandson, surrendered at the end after being surrounded by Xiongnu forces. One year later, receiving a report that Li Ling was training Xiongnu soldiers, Emperor Wu had Li's clan executed.

Moreover, Emperor Wu already bore a grudge against the famed historian Sima Qian because Sima's Shiji[29] was not as flattering to Emperor Wu and his father Emperor Jing as Emperor Wu wanted, so Emperor Wu had Sima Qian castrated.

In 106 BC, in order to further better organize the territories, including both the previously existing empire and the newly conquered territories, Emperor Wu divided the empire into 13 prefectures (zhou, 州), but without governors or prefectural governments. Rather, he assigned a supervisor to each prefecture, who would visit the commanderies and principalities in the prefecture on a rotating basis to investigate corruption and disobedience with imperial edicts.

In 104 BC, Emperor Wu built the luxurious Jianzhang Palace (建章宮) – a massive structure that was intended to make him closer to the gods. He later resided at that palace exclusively, rather than the traditional Weiyang Palace, which Xiao He had built during the reign of Emperor Gao.

About 100 BC, due to the heavy taxation and military burdens imposed by Emperor Wu's incessant military campaigns and luxurious spending, there were many peasant revolts throughout the empire. Emperor Wu issued an edict that was intended to suppress the peasant revolts: he made officials whose commanderies saw unsuppressed peasant revolts liable with their lives. However, this edict had the exact opposite effect, since it became impossible to suppress all of the revolts, officials would merely cover up the existence of the revolts. He executed many people who made fake coins.[30]

In 96 BC, a series of witchcraft persecutions began. Emperor Wu, who was paranoid over a nightmare of being whipped by tiny stick-wielding puppets and a sighting of a traceless assassin (possibly a hallucination), ordered extensive investigations with harsh punishments. Large numbers of people, many of them high officials, were accused of witchcraft and executed, usually along with their entire clans.[31] The first trial began with Empress Wei Zifu's elder brother-in-law Gongsun He (公孫賀, the Prime Minister at the time) and his son Gongsun Jingsheng (公孫敬聲, also an imperial official, but arrested under corruption charges), quickly leading to the execution of their entire clan. Also caught in this disaster were Crown Prince Ju's two elder sisters Princess Yangshi (陽石公主, who was said to have a romantic relationship with her cousin Gongsun Jingsheng) and Princess Zhuyi (諸邑公主), as well as his cousin Wei Kang (衛伉, the eldest son of the deceased general Wei Qing), who were all accused of witchcraft and executed in 91 BC. These witchcraft persecutions later became intertwined in succession struggles and erupted into a major catastrophe.

Crown Prince Ju's revolt

In 94 BC, Emperor Wu's youngest son Liu Fuling was born to a favorite concubine of his, Lady Gouyi (Consort Zhao). Emperor Wu was ecstatic in having a child at such an advanced age (62 years old), and because Consort Zhao purportedly had a pregnancy that lasted 14 months (the same as the mythical Emperor Yao), he named Consort Zhao's palace gate "Gate of Yao's mother." This led to speculation that the emperor, due to his favor of Consort Zhao and Prince Fuling, wanted to make Liu Fuling the crown prince instead. While there was no evidence that he actually intended to do anything as such, over the next few years, conspiracies against Crown Prince Ju and his mother Empress Wei arose that were inspired by such rumors.

Up to this point, there had been a cordial but somehow fragile relationship between Emperor Wu and his crown prince, who perhaps was not as ambitious as his father wished. As he grew older, the Emperor came to be less attracted to Ju's mother, Empress Wei Zifu, though he continued to respect her. When he left the capital, the Emperor would delegate authority to Crown Prince Ju. Eventually, however, the two began to have disagreements over policy, with Ju favoring leniency and Wu's advisers (harsh and sometimes corrupt officials) urging the opposite. After Wei Qing's death in 106 BC and Gongsun He's execution, Prince Ju had no strong allies left in the government. The other officials then began to publicly defame and plot against him. Meanwhile, Emperor Wu was becoming more and more isolated, spending time with young concubines, often remaining unavailable to Ju or Wei.

Conspirators against Prince Ju included Jiang Chong (江充), the newly appointed head of secret intelligence, who had once had a run-in with Ju after arresting one of his assistants for improper use of an imperial right of way. Another conspirator was Su Wen (蘇文), chief eunuch in charge of caring for imperial concubines, who had previously made false accusations against Ju, claiming he was joyful over Wu's illness and had an adulterous relationship with one of the junior concubines.

Jiang and others made many accusations of witchcraft against important people in the Han court. Jiang and Su decided to use witchcraft as the excuse to move against Prince Ju himself. With approval from Emperor Wu who was then at the Ganquan Palace, Jiang searched through various palaces, ostensibly for witchcraft items, eventually reaching Prince Ju's and Empress Wei's palace. While completely trashing the palaces up with intensive digging, he secretly planted witchery dolls and pieces of cloth with mysterious writings. He then announced that he had found the items there during the search. Prince Ju was shocked, knowing that he was framed. His teacher Shi De (石德), invoking the story of Ying Fusu of the Qin dynasty and raised the possibility that Emperor Wu might already be dead, suggesting that Prince Ju start an uprising to fight the conspirators. Prince Ju initially hesitated, wanting to speed to Ganquan Palace to defend himself before his father. But, when he found out that Jiang's messengers were already on their way, he decided to follow Shi's suggestion.

Prince Ju sent an individual to impersonate a messenger from Emperor Wu to lure and arrest Jiang and the other conspirators. Su escaped, but Ju accused Jiang of sabotaging his relationship with his father, and personally killed Jiang. With the support of his mother, Ju enlisted his guards, civilians, and prisoners in preparation to defend him.

Su fled to Ganquan Palace and accused Prince Ju of treason. Emperor Wu, not believing it to be true and correctly (at this point) believing that Prince Ju had merely been angry at Jiang, sent a messenger back to Chang'an to summon Prince Ju. The messenger did not dare to proceed to Chang'an, but instead returned and gave Emperor Wu the false report that Prince Ju was conducting a coup. Enraged, Emperor Wu ordered his nephew, Prime Minister Liu Qumao (刘屈犛), to put down the rebellion.

The two sides battled in the streets of Chang'an for five days, but Liu Qumao's forces prevailed after it became clear that Prince Ju did not have his father's authorization. Prince Ju was forced to flee the capital following the defeat, accompanied only by two of his sons and some personal guards. Apart from a grandson Liu Bingyi, who was barely a month old and thrown into prison, all other members of his family were left behind and killed. His mother, Empress Wei, committed suicide when Emperor Wu sent officials to depose her. Their bodies were carelessly buried in fields without proper tomb markings. Prince Ju's supporters were brutally cracked down on and civilians aiding the crown prince were exiled. Even Tian Ren (田仁), an official city gatekeeper who did not stop Prince Ju's escape, and Ren An (任安), an army commander who chose not to actively participate in the crackdown, were accused of being sympathizers and executed.

Emperor Wu continued to be enraged and ordered that Prince Ju be tracked down. After a junior official, Linghu Mao (令狐茂), risked his life to speak on Prince Ju's behalf, Emperor Wu's anger began to subside. However, he waited to issue a pardon for Prince Ju.

Prince Ju fled to Hu County (湖縣, in modern Sanmenxia, Henan) and took refuge in the home of a poor peasant family. Knowing that their good-hearted hosts could never afford the daily expenditure of so many people, the Prince sought help from an old friend who lived nearby. However, this move exposed their whereabouts, and he was soon tracked down by local officials eager for a reward. Surrounded by troops and seeing no chance of escape, the Prince hung himself. His two sons and the family housing them died with him after the government soldiers eventually broke into the yard and killed everyone. The two local officials who led the raid, Zhang Fuchang (張富昌) and Li Shou (李寿), wasted no time in taking the Prince's body to Chang'an to claim a reward from the emperor. Emperor Wu, although greatly saddened to hear the death of his son, had to keep his promise and rewarded the officials.

Late reign and death

Even after Jiang Chong and Prince Ju both died, the witchhunt continued and combined with Wei Zifu's jealousy led to the execution of the Li family on accounts of treason. General Li Guangli caused unnecessary losses with his military incompetence. In 90 BC, while Li was assigned to a campaign against Xiongnu, a eunuch named Guo Rang (郭穰) exposed how Li and his political ally, Prime Minister Liu Qumao, were conspiring to use witchcraft on Emperor Wu. Liu and his family were immediately arrested and later executed. Li's family was also taken into custody and later executed after the traitor Li Ling also defected to the Xiongnu. Li, after learning the news, used risky tactics to attempt a standoff against Emperor Wu, but failed when some of his senior officers mutinied. On his retreat, he was ambushed by Xiongnu forces. He defected to Xiongnu and Emperor Wu executed the Li clan for treason soon after. Even within the Xiongnu, Li himself also fought with other Han traitors, especially Wei Lü (衛律), who was extremely jealous of the amount of Chanyu's favor that Li gained as a new, high-profile defector.

By this time, Emperor Wu realized that the witchcraft accusations were often false accusations, especially in relation to the crown prince rebellion. In 92 BC, when Tian Qianqiu, then the superintendent of Emperor Gao's temple, wrote a report claiming that Emperor Gao told him in a dream that Prince Ju should have only been whipped at most, not killed, Emperor Wu had a revelation about what had led to his son's rebellion. He had Su burned and Jiang's family executed. He also made Tian prime minister. Although he claimed to miss Prince Ju greatly (he even built a palace and an altar for his deceased son as a sign of grief and regret), he did not at this time rectify the situation where Prince Ju's only surviving progeny, Liu Bingyi, languished in prison as a child.

With the political scene greatly changed, Emperor Wu publicly apologized to the whole nation about his past policy mistakes, a gesture known to history as the Repenting Edict of Luntai (輪台悔詔). The Prime Minister Tian he appointed was in favor of retiring the troops and easing hardships on the people. Tian also promoted agriculture, with several agricultural experts becoming important members of the administration. Wars and territorial expansion generally ceased. These policies and ideals were those supported by Crown Prince Ju, and were finally realised years after his death.

By 88 BC, Emperor Wu had become seriously ill. With Prince Ju dead, there was no clear heir. Liu Dan, the Prince of Yan, was Emperor Wu's oldest surviving son, but Emperor Wu considered both him and his younger brother Liu Xu, the Prince of Guangling, to be unsuitable, since neither respected laws. He decided that the only suitable heir was his youngest son, Liu Fuling, who was only six at that time. He therefore also chose a potential regent in Huo Guang, whom he considered to be capable and faithful, and entrusted Huo with the regency of Fuling. Emperor Wu also ordered the execution of Prince Fuling's mother Consort Zhao, out of fear that she would become an uncontrollable empress dowager with full power like the previous Empress Lü. At Huo's suggestion, he made ethnic Xiongnu official Jin Midi and general Shangguang Jie co-regents. He died in 87 BC, shortly after making Prince Fuling crown prince. Crown Prince Fuling then succeeded to the throne as Emperor Zhao for the next 13 years.

Empress Chen Jiao and Empress Wei Zifu were the only two empresses during Emperor Wu's reign. Emperor Wu did not make anyone empress after Empress Wei Zifu committed suicide, and he left no instruction on who should be enshrined in his temple with him. He lies buried in the Maoling mound, the most famous of the so-called Chinese pyramids. Huo Guang sent 500 beautiful women there for the dead emperor.[32] According to folk legend, 200 of them were executed for having sex with the guards. Huo's clan was later killed and the emperor's tomb was looted by Chimei.

Legacy

Historians have treated Emperor Wu with ambivalence, and there are certainly some contradictory accounts of his life. He roughly doubled the size of the Han empire of China during his reign, and much of the territory that he annexed is now part of modern China. He officially encouraged Confucianism, yet just like Qin Shi Huang, he personally used a legalist system of rewards and punishments to govern his empire.

Emperor Wu is said to have been extravagant and superstitious, allowing his policies to become a burden on his people. As such he is often compared to Qin Shi Huang.[33] The punishments for perceived failures and disloyalty were often exceedingly harsh. His father saved many participants of Rebellion of the Seven States from execution, and made some work in constructing his tomb.[34] Emperor Wu had killed thousands of people and their families over the Liu An affair, Hengshan,[35] his prosecution of witchcraft, and the Prince Ju revolt.[36]

He used some of his wives' relatives to fight Xiongnu, some of whom become successful and famous generals. There is evidence to suggest that the two of them, Wei Qing and Huo Qubin, may have been his lovers.[37] Wei Qing was buried in the Emperor's mausoleum.

He forced his last queen to commit suicide. His lover, Han Yuan, whom he had known since childhood, was executed on the Queen Dowager's orders for having an affair with a palace maid.[37] Out of the twelve prime ministers appointed by Emperor Wu, three were executed and two committed suicide while holding the post; another was executed in retirement. He set up many special prisons (詔獄) and incarcerated nearly two hundred thousand individuals in them.[38]

Emperor Wu's political reform resulted in the strengthening of the Emperor's power at expense of the prime minister's authority. The post of Shangshu (court secretaries) was elevated from merely managing documents to that of the Emperor's close advisor, and it stayed this way until the end of the imperial era.

In 140 BC, Emperor Wu conducted an imperial examination of over 100 young scholars. Having been recommended by officials, most of the scholars were commoners with no noble background. This event would have a major impact on Chinese history, marking the official start of the establishment of Confucianism as official imperial doctrine. This came about because a young Confucian scholar, Dong Zhongshu, was evaluated to have submitted the best essay in which he advocated the establishment of Confucianism. It is unclear whether Emperor Wu, in his young age, actually determined this, or whether this was the result of machinations of the prime minister Wei Wan (衛綰), who was himself a Confucian. However, the fact that several other young scholars who scored highly on the examination (but not Dong) later became trusted advisors for Emperor Wu would appear to suggest that Emperor Wu himself at least had some actual participation.[39]

In 136 BC, Emperor Wu founded what became the Imperial University, a college for classical scholars that supplied the Han's need for well-trained bureaucrats.[40]

Poetry

Various important aspects of Han poetry are associated with Emperor Wu and his court, including his direct interest in poetry and patronage of poets. Emperor Wu was also a patron of literature, with a number of poems being attributed to him.[41] As to the poetry on lost love, some of the pieces attributed to him are considered of well-done, there is some question to their actual authorship.[41]

The following work is on the death of one of his concubines:[42]

The sound of her silk skirt has stopped.

On the marble pavement dust grows.

Her empty room is cold and still.

Fallen leaves are piled against the doors.

How can I bring my aching heart to rest?[43]

— On the Death of Li Fu-ren

Emperor Wu facilitated a revival of interest in Chu ci, the poetry of and in the style of the area of the former Chu kingdom during the early part of his reign, in part because of his near relative Liu An.[44] Some of this Chu material was later anthologized in the Chu Ci.

The Chuci genre of poetry from its origin was linked with Chu shamanism, and Han Wudi both supported the Chu genre of poetry in the earlier years of his reign, and also continued to support shamanically linked poetry during the later years of his reign.

Emperor Wu employed poets and musicians in writing lyrics and scoring tunes for various performances and also patronized choreographers and shamans in this same connection for arranging the dance movements and coordinating the spiritual and the mundane. He was quite fond of the resulting lavish ritual performances, especially night time rituals where the multitudinous singers, musicians, and dancers would perform in the brilliant lighting provided by of thousands of torches.[45]

The fu style typical of Han poetry also took shape during the reign of Emperor Wu in his court, with poet and official Sima Xiangru as a leading figure. However, Sima's initial interest in the chu ci style later gave way to his interest in more innovative forms of poetry. After his patronage of poets familiar with the Chu ci style in the early part of his reign, Emperor Wu later seems to have turned his interest and his court's interest to other literary fashions.[44]

Another of Emperor Wu's major contribution to poetry was through his organization of the Imperial Music Bureau (yuefu) as part of the official governmental bureaucratic apparatus: the Music Bureau was charged with matters related to music and poetry, as lyrics are a part of music and traditional Chinese poetry was considered to have been chanted or sung, rather than spoken or recited as prose. The Music Bureau greatly flourished during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han,[46] who has been widely cited to have founded the Music Bureau in 120 BCE.[47]

However, it seems more likely that there was already a long-standing office of music and that Emperor Wu enlarged its size as part of his governmental reorganization, changing its scope and function and possibly renaming it and thus seeming to have established a new institution. The stated tasks of this institution were apparently to collect popular songs from different and adapt and orchestrate these, as well as to develop new material.[48] Emperor Wu's Music Bureau not only collected folk songs and ballads from where they originated throughout the country, but also collected songs reportedly based on Central Asian tunes or melodies, with new lyrics which were written to harmonize with the existing tunes, and characterized by varying line lengths and the incorporation of various nonce words.[49] In any case, he is widely held to have used the Music Bureau as an important part of his religious innovations and to have specifically commissioned Sima Xiangru to write poetry.[50] Because of the development and transmission of a particular style of poetry by the Music Bureau, this style of poetry has become known as the "Music Bureau" style, or yuefu (and also in its later development referred to as "new yuefu", "imitation", or "literary yüeh-fu").

Era names

- Jianyuan (建元) 140 BC – 135 BC

- Yuanguang (元光) 134 BC – 129 BC

- Yuanshuo (元朔) 128 BC – 123 BC

- Yuanshou (元狩) 122 BC – 117 BC

- Yuanding (元鼎) 116 BC – 111 BC

- Yuanfeng (元封) 110 BC – 105 BC

- Taichu (太初) 104 BC – 101 BC

- Tianhan (天漢) 100 BC – 97 BC

- Taishi (太始) 96 BC – 93 BC

- Zhenghe (征和) 92 BC – 89 BC

- Houyuan (後元) 88 BC – 87 BC

Family

Consorts and Issue:

- Empress Chen, of the Chen clan (皇后 陳氏; 166/165–c. 110 BC), first cousin, personal name Jiao (嬌)

- Empress Xiaowusi, of the Wei clan (孝武思皇后 衛氏; d. 91 BC), personal name Zifu (子夫)

- Lady Li, of the Li clan (李氏), personal name Yan (妍)

- Liu Bo, Prince Ai of Changyi (昌邑哀王 劉髆; d. 88 BC), fifth son

- Lady Guoyi, of the Zhao clan (皇太后 趙氏; 113–88 BC)

- Liu Fuling, Emperor Xiaozhao (孝昭皇帝 劉弗陵; 94–74 BC), sixth son

- Furen, of the Wang clan (夫人 王氏; d. 121 BC)

- Liu Hong, Prince Huai of Qi (齊懷王 劉閎; 123–110 BC), second son

- Furen, of the Yin clan (夫人 尹氏)

- Lady, of the Xing clan (邢氏), personal name Xing'e (娙娥)

- Lady, of the Li clan (李氏)

- Liu Dan, Prince La of Yan (燕剌王 劉旦; d. 80 BC), third son

- Liu Xu, Prince Li of Guangling (廣陵厲王 劉胥; d. 54 BC), fourth son

- Gongren, of the Li clan (宫人 丽氏), personal name Juan (娟)

- Unknown

- Princess Eyi (鄂邑公主; d. 80 BC)

- Married, and had issue (one son)

- Princess Yangshi (阳石公主, d. 92)

- Princess Yi'an (夷安公主)

- Princess Eyi (鄂邑公主; d. 80 BC)

Ancestry

| Liu Taigong (282–197 BC) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor Gaozu of Han (256–195 BC) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Zhaoling | |||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor Wen of Han (203–157 BC) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Gao (d. 155 BC) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Lady Wei | |||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor Jing of Han (188–141 BC) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Dou Chong | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Xiaowen (d. 135 BC) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor Wu of Han (157–87 BC) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Wang Zhong | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Xiaojing (d. 126 BC) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Zang Tu (d. 202 BC) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Zang Er | |||||||||||||||||||

Cultural depictions

Emperor Wu is one of the most famous emperors of ancient China and has made appearances in quite a lot of Chinese television dramas, examples include:

- The Prince of Han Dynasty

- The Emperor in Han Dynasty

- Beauty's Rival in Palace

- The Virtuous Queen of Han

Emperor Wu is also a major character in Carole Wilkinson's novel Dragonkeeper and its sequels, Garden of the Purple Dragon and Dragon Moon. The three novels, which center on the journeys of a former slave girl and the dragons in her care, loosely depict the first years of Emperor Wu's reign and includes a number of references to his quest for immortality.

In the 1991 film "The Addams Family" Morticia Addams donates "a finger trap from the court of Emperor Wu" to a charity auction.

See also

Notes

- Had his name changed into the more suitable Che when he was officially made crown prince in April 150 BC.

- This courtesy name is reported by Xun Yue (148–209), the author of the Annals of Han (《漢紀》), but other sources do not mention a courtesy name.

- Meaning "martial emperor".

- Meaning "filial and martial august sovereign".

References

- Ban Biao; Ban Gu (n.d.). Han Shu (History Of The Former Han Dynasty). See also Ulrich Theobald, ed. (2010). "Han Shu". ChinaKnowledge.de.

- Popular Songs and Ballads of Han China. Translated by Birrell, Anne. London: Allen & Unwin. 1988. ISBN 9780044400370.

- Cosmo, Nicola Di (2002). Ancient China and its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History (Updated ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521770644.

- The Songs of the South: An Anthology of Ancient Chinese Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets. Translated by Hawkes, David. Penguin. 2011 [1985]. ISBN 9780140443752.

- Paludan, Ann; Wilkinson, Toby A.; Mcqueen, David (1998). Chronicle of the Chinese Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial China (1st ed.). New York City: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500050903.

- Peers, Chris J. (1995). Imperial Chinese Armies Vol. 1: 200 BC-AD 589. Men at Arms No. 284. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781855325142.

- Pollard, Elizabeth; Rosenberg, Clifford; Tignor, Robert (2015). Worlds Together Worlds Apart. Volume One - Beginning Through the 15th Century (concise ed.). New York City: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393918472.

- Yü, Ying-shih (1986). "Han Foreign Relations". In Denis Twitchett; Michael Loewe (eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 1: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 377–462. ISBN 9780521243278.

Footnotes

- dingmao day of the 2nd month of the 2nd year of the Hou'yuan era, per Emperor Wu's biography in Book of Han

- Loewe, Michael (2005). Crisis and Conflict in Han China (Reprint ed.). Milton Park GB-OXF: Routledge. p. 118. ISBN 9780415361613.

- Pollard et al (2015), p. 238.

- Bo Yang's commentary in the Modern Chinese edition of Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 7, and Zhao Yi (趙翼)'s commentary included therein.

- Mark Csikszentmihalyi 2006 p.xxiv, xix Readings in Han Chinese Thought.

- Creel, Herrlee Glessner (1953). Chinese Thought from Confucius to Mao Tse-tung. University of Chicago Press. pp. 166–71. (1971) ISBN 9780226120300.

- Creel, Herrlee Glessner (1982) [1970]. What Is Taoism? And Other Studies in Chinese Cultural History. University of Chicago Press. p. 115. ISBN 9780226120478.

- Paludan et al (1998), p. 36.

- Paludan et al (1998), p. 37.

- (大中大夫公孙卿、壶遂、太史令司马迁等言:“历纪坏废,宜改正朔。”上诏兒宽与博士赐等共议,以为宜用夏正。夏,五月,诏卿、遂、迁等共造汉《太初历》,以正月为岁首...) Zizhi Tongjian, vol.21

- jisi day of the 4th month of the 4th year of Emperor Jing's reign, per vol.16 of Zizhi Tongjian. This was the same day Liu Rong was made Crown Prince.

- 汉·班固《汉武故事》Ban Gu, Story of Han Wudi (汉武故事)

- Cosmo, Nicola Di (1999). "The Northern Frontier in Pre-Imperial China". In Michael Loewe; Edward L. Shaughnessy (eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 892–3 (885-966). ISBN 9780521470308.

- Yü (1986), p. 390; Cosmo (2002), pp. 237–9.

- Paludan et al (1998), p. 38.

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. (6 vols.) (1st ed.). Santa Barbara CA: ABC-Clio. p. 109. ISBN 9781851096671.

- Yü (1986), p. 390; Cosmo (2002), p. 240.

- Barfield, Thomas J. (2001). "The Shadow Empires: Imperial State Formation Along the Chinese-Nomad Frontier". In Susan E. Alcock; Kathleen D. Morrison; Terence N. D'altroy; Carla M. Sinopoli (eds.). Empires: Perspectives from Archaeology and History (1st ed.). New York City: Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 9780521770200.

- Yü (1986), pp. 448–9, 451–3.

- Pai, Hyung Il (February 1992). "Culture Contact and Culture Change: The Korean Peninsula and Its Relations with the Han Dynasty Commandery of Lelang". World Archaeology. 23 (3 - Archaeology of Empires): 306–319. doi:10.1080/00438243.1992.9980182. pp. 310–5.

- Hawkes (2011), p. 98.

- Hawkes (2011), p. 100.

- Hawkes (2011), pp. 42, 97.

- Hawkes (2011), p. 118.

- Hawkes (2011), p. 119.

- Zhongshu Dong; John S. Major, Sarah A. Queen (2015). Luxuriant Gems of the Spring and Autumn. Columbia University Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0231539616.

- Peers 1995, p. 7.

- Peers 1995, p. 8.

- Sima Qian. Shi Ji (Historical Records or Records of the Grand Historian): Biography of Han Wudi.

- Han Shu, vol. 24.

- Meyer, Milton W. (1997). Asia: a concise history. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780847680689. OCLC 33276519.

- 漢武故事

- Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 22.

- 院重大B类课题"东汉洛阳刑徒墓"完成结项 Archived 2011-07-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Han Shu, vol. 44.

- Han Shu, vol. 45.

- B.C., Sima, Qian, approximately 145 B.C.-approximately 86 (1993). Records of the grand historian. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08164-2. OCLC 904733341.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Zhao Yi's 廿二史劄記, vol. 3

- Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 17.

- Pollard et al & (2015), p. 239.

- Rexroth, Kenneth (1970). Love and the Turning Year: One Hundred More Poems from the Chinese. New York: New Directions. p. 133.

- Morton, W. Scott (1995). China: Its History and Culture (3rd ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 54. ISBN 9780070434240.

- Translation by Arthur Waley, 1918 (One Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems).

- Hawkes (2011), p. 29.

- Hawkes (2011), p. 97.

- Birrell (1988), pp. 5–6.

- Birrell (1988), p. 7.

- Birrell (1988), pp. 6–7.

- Watson, Burton (1971). CHINESE LYRICISM: Shih Poetry from the Second to the Twelfth Century. (New York, NY: Columbia University Press). p. 53. ISBN 0-231-03464-4

- Birrell (1988), p. 6.

Further reading

- Ban Gu. Han Shu: Biography of Han Wudi.

- Sima Guang. Zizhi Tongjian (Comprehensive Mirror to Aid in Government): Modern Chinese Edition edited by Bo Yang (Taipei, 1982–1989).

- Wu, John C. H. (1972). The Four Seasons of Tang Poetry. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle. ISBN 978-0804801973

- Yap, Joseph P. (2009). Wars With The Xiongnu, A Translation from Zizhi tongjian. AuthorHouse, Bloomington, Indiana. ISBN 978-1449006044. Chapters 3–7.

- Xun Yue. Han Ji.