Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP), formerly known as bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP), is an inflammation of the bronchioles (bronchiolitis) and surrounding tissue in the lungs.[2][3] It is a form of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia.[4]

| Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia, idiopathic interstitial pneumonia[1] |

| |

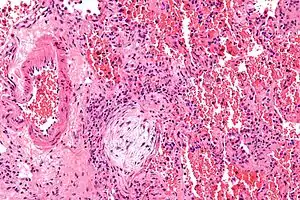

| Micrograph showing a Masson body (off center left/bottom of the image – pale circular and paucicellular), as may be seen in cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. The Masson body plugs the airway. The artery associated with the obliterated airway is also seen (far left of the image). H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

| Symptoms | cough, labored breathing, fever, fatigue, unexpected weight loss[1] |

It is often a complication of an existing chronic inflammatory disease such as rheumatoid arthritis, dermatomyositis, or it can be a side effect of certain medications such as amiodarone. COP was first described by Gary Epler in 1985.[5]

The clinical features and radiological imaging resemble infectious pneumonia. However, diagnosis is suspected after there is no response to multiple antibiotics, and blood and sputum cultures are negative for organisms.

Terminology

"Organizing" refers to unresolved pneumonia (in which the alveolar exudate persists and eventually undergoes fibrosis) in which fibrous tissue forms in the alveoli. The phase of resolution and/or remodeling following bacterial infections is commonly referred to as organizing pneumonia, both clinically and pathologically.

The American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society hold that "cryptogenic organizing pneumonia" is the preferred clinical term for this disease for multiple reasons:[6][7]

- Avoid confusion with bronchiolitis obliterans, which may not be visualized in every case of this disease.

- Avoid confusion with constrictive bronchiolitis

- Emphasize the cryptogenic nature of the disease

Signs and symptoms

The classic presentation of COP is the development of nonspecific systemic (e.g., fevers, chills, night sweats, fatigue, weight loss) and respiratory (e.g. difficulty breathing, cough) symptoms in association with filling of the lung alveoli that is visible on chest x-ray.[8] This presentation is usually so suggestive of an infection that the majority of patients with COP have been treated with at least one failed course of antibiotics by the time the true diagnosis is made.[8] Symptoms are usually subacute, occurring over weeks to months with dry cough (seen in 71% of people), dyspnea (shortness of breath)(62%) and fever (44%) being the most common symptoms.[9]

Causes

- Pulmonary infection by bacteria, viruses and parasites

- Drugs: antineoplastic drugs, erlotinib, amiodarone

- Chemical exposure, most notably to diacetyl[10]

- Vaping: On October 17, 2019, the American Journal of Clinical Pathology reported that lung biopsies from patients with vaping-associated pulmonary illness show acute lung injury patterns, including organizing pneumonia.[11]

- Ionizing radiations[12][13]

- Inflammatory diseases

- Systemic lupus

- Rheumatoid arthritis (RA-associated COP)

- Scleroderma

- Bronchial obstruction

- SARS-CoV-2

- Analysis of COVID-19 CT imaging along with postmortem lung biopsies and autopsies suggest that the majority of patients with COVID-19 pulmonary involvement also have secondary organizing pneumonia (OP) or its histological variant, acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia, which are both well-known complications of viral infections. [15]

It was identified in 1985, although its symptoms had been noted before but not recognised as a separate lung disease. The risk of COP is higher for people with inflammatory diseases like lupus, dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis, and scleroderma.[16] It most commonly presents in the 5th or 6th decade of life and it is exceedingly rare in children.[9][17]

Pathophysiology

Organizing pneumonia is usually preceded by some type of lung injury that causes a localized denudation or disruption in continuity of the epithelial basal laminae of the type 1 alveolar pneumocytes that line the alveoli.[9] This injury to the epithelial basal lamina results in inflammatory cells and plasma proteins leaking into the alveolar space and forming fibrin, resulting in an initial fibroblast driven intra-alveolar fibroproliferation.[9] The fibroblasts differentiate into myofibroblasts and continue to form fibrosis resulting in intra-alveolar fibroinflammatory buds (Masson's Bodies) that are characteristic of organizing pneumonia.[9] These Masson's bodies consist of inflammatory cells contained in an extracellular matrix consisting of type I collagen, fibronectin, procollagen type III, tenascin C and proteoglycans.[9] Angiogenesis , or the formation of blood vessels, occurs in the Masson's bodies and this is driven by vascular endothelial growth factor.[9] Remodeling occurs, resulting in the intra-alveolar fibroinflammatory buds (Masson's Bodies) moving into the interstitial space and forming collagen globules that are then covered by type 1 alveolar epithelial cells with well developed basement membranes. These type 1 alveolar epithelial cells (pneumocytes) then proliferate, restoring the continuity and function of the alveolar unit.[9] This process is in contrast to the histopathologic changes seen in usual interstitial pneumonia where extensive fibrosis and inflammation occur leading to fibroblastic foci to form in the alveolar spaces resulting in obliteration of the alveolar space, scarring and significant damage to lung architecture (the alveoli).[9]

Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (which inhibit breakdown of the extracellular matrix connective tissue) are more active in usual interstitial pneumonia as compared to organizing pneumonia, this is thought to lead to a greater deposition of connective tissue in the alveolar space in interstitial pneumonia as compared to organizing pneumonia and may explain the progressive, irreversible fibrosis seen in usual interstitial pneumonia.[9] Gelatinolytic activity (resulting in the breakdown of extracellular matrix connective tissue) is greater in organizing pneumonia as compared to usual interstitial pneumonia, and this is thought to contribute to the reversible fibroproliferation characteristic of organizing pneumonia.[9]

Diagnosis

On clinical examination, crackles are common, and more rarely, patients may have clubbing (<5% of cases). Laboratory findings are nonspecific but inflammatory markers such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein and the lymphocyte count are frequently elevated.[9] If the organizing pneumonia is secondary to a connective tissue disorder, then the associated laboratory values such as the anti-nuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, anti-citrullinated protein antibodies, anti-dsDNA antibodies and other similar connective tissue associated antibodies are elevated.[9]

Pulmonary function testing in people with organizing pneumonia, either cryptogenic or due to secondary causes, shows a restrictive defect with a decrease in the gas absorptive capacity of the lungs (seen as a decrease in the diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide).[9] Airflow obstruction is usually not seen on pulmonary function testing.[9]

Bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage is recommended in possible cases of organizing pneumonia to rule out infection and other causes of alveolar infiltrates.[9] The bronchoalveolar lavage in organizing pneumonia shows a lymphocytic predominant inflammation of the alveoli with increases in neutrophils and eosinophils.[9] Resolution of inflammatory cells in the bronchoalveolar lavage is usually delayed in organizing pneumonia, lagging behind clinical and radiographic improvement.[9]

Biopsy findings in patients with organizing pneumonia consist of loose connective tissue plugs involving the alveoli, alveolar ducts and bronchioles. The loose connective tissue plugs occupying the alveolar spaces often connect to other connective tissue plugs in nearby alveoli via the pores of Kohn creating a characteristic butterfly pattern on histology.[9] There is usually minimal to no interstitial inflammatory changes in biopsies of organizing pneumonia.[9]

Imaging

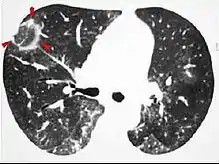

The chest x-ray is distinctive with features that appear similar to an extensive pneumonia, with both lungs showing widespread white patches. The white patches may seem to migrate from one area of the lung to another as the disease persists or progresses. Computed tomography (CT) may be used to confirm the diagnosis. Often the findings are typical enough to allow the doctor to make a diagnosis without ordering additional tests.[19] To confirm the diagnosis, a doctor may perform a lung biopsy using a bronchoscope. Many times, a larger specimen is needed and must be removed surgically.

Plain chest radiography shows normal lung volumes, with characteristic patchy unilateral or bilateral consolidation. Small nodular opacities occur in up to 50% of patients and large nodules in 15%. On high resolution computed tomography, airspace consolidation with air bronchograms is present in more than 90% of patients, often with a lower zone predominance. A subpleural or peribronchiolar distribution is noted in up to 50% of patients. Ground glass appearance or hazy opacities associated with the consolidation are detected in most patients.

Histologically, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia is characterized by the presence of polypoid plugs of loose organizing connective tissue (Masson bodies) within alveolar ducts, alveoli, and bronchioles.

Unusual presentations of organizing pneumonia

While patchy bilateral disease is typical, there are unusual variants of organizing pneumonia where it may appear as multiple nodules or masses. One rare presentation, focal organizing pneumonia, may be indistinguishable from lung cancer based on imaging alone, requiring biopsy or surgical resection to make the diagnosis.[20]

Complications

Rare cases of COP have induced with lobar cicatricial atelectasis.[21]

Treatment

Systemic steroids are considered the first line treatment for organizing pneumonia, with patient's often having clinical improvement within 72 hours of steroid initiation and most patient's achieving recovery.[22][9] A prolonged treatment course is indicated, with patients usually requiring at least 4-6 months of treatment.[9] Patient's who are treated with larger doses of steroids require prophylaxis against pneumocystis jirovecii.[9] Relapses may occur and are more likely to occur in severe disease or when steroids are tapered too soon or too quickly.[9] Alternative or adjunct treatment options include macrolide antibiotics (due to anti-inflammatory properties), azathioprine and cyclophosphamide.[9]

References

- "Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia". Autoimmune Registry Inc. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- "bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- White, Eric J. Stern, Charles S. (1999). Chest radiology companion. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-397-51732-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia - Pulmonary Disorders".

- Epler GR (June 2011). "Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia, 25 years: a variety of causes, but what are the treatment options?". Expert Rev Respir Med. 5 (3): 353–61. doi:10.1586/ers.11.19. PMID 21702658. S2CID 207222916.

- Joseph F. Tomashefski; Carol Farver; Armando E. Fraire (2009). Dail and Hammar's Pulmonary Pathology: Volume I: Nonneoplastic Lung Disease (3rd ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 64. ISBN 9780387687926.

- Geddes DM (August 1991). "BOOP and COP". Thorax. 46 (8): 545–7. doi:10.1136/thx.46.8.545. PMC 463266. PMID 1926020.

- "Pulmonary Question 27: Diagnose cryptogenic organizing pneumonia". MKSAP 5 For Students Online. American College of Physicians. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- King, Talmadge E.; Lee, Joyce S. (17 March 2022). "Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia". New England Journal of Medicine. 386 (11): 1058–1069. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2116777. PMID 35294814. S2CID 247498540.

- Levy, Barry S.; Wegman, David H.; Baron, Sherry L.; Sokas, Rosemary K., eds. (2011). Occupational and environmental health recognizing and preventing disease and injury (6th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 414. ISBN 9780199750061. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- Mukhopadhyay, Sanjay; Mehrad, Mitra; Dammert, Pedro; Arrossi, Andrea V; Sarda, Rakesh; Brenner, David S; Maldonado, Fabien; Choi, Humberto; Ghobrial, Michael (2019). "Lung Biopsy Findings in Severe Pulmonary Illness Associated With E-Cigarette Use (Vaping): A Report of Eight Cases". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 153 (1): 30–39. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqz182. ISSN 0002-9173. PMID 31621873.

- Nogi, S; Nakayama, H; Tajima, Y; Okubo, M; Mikami, R; Sugahara, S; Akata, S; Tokuuye, K (2014). "Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia associated with radiation: A report of two cases". Oncology Letters. 7 (2): 321–324. doi:10.3892/ol.2013.1716. PMC 3881924. PMID 24396439.

- Oie, Y; Saito, Y; Kato, M; Ito, F; Hattori, H; Toyama, H; Kobayashi, H; Katada, K (2013). "Relationship between radiation pneumonitis and organizing pneumonia after radiotherapy for breast cancer". Radiation Oncology. 8: 56. doi:10.1186/1748-717X-8-56. PMC 3605133. PMID 23497657.

- Radzikowska, E; Nowicka, U; Wiatr, E; Jakubowska, L; Langfort, R; Chabowski, M; Roszkowski, K (2007). "Organising pneumonia and lung cancer - case report and review of the literature". Pneumonologia I Alergologia Polska. 75 (4): 394–7. PMID 18080991.

- Kory, Pierre; Kanne, Jeffrey P (2020-09-22). "SARS-CoV-2 organizing pneumonia:'Has there been a widespread failure to identify and treat this prevalent condition in COVID-19?'". BMJ. 7 (1): e000724. doi:10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000724. PMC 7509945. PMID 32963028.

- Al-Ghanem Sara; Al-Jahdali Hamdan; Bamefleh Hanaa; Khan Ali Nawaz (Apr–Jun 2008). "Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia: Pathogenesis, clinical features, imaging and therapy review". Ann Thorac Med. 3 (2): 67–75. doi:10.4103/1817-1737.39641. PMC 2700454. PMID 19561910.

- Drakopanagiotakis, Fotios; Paschalaki, Koralia; Abu-Hijleh, Muhanned; Aswad, Bassam; Karagianidis, Napoleon; Kastanakis, Emmanouil; Braman, Sidney S.; Polychronopoulos, Vlasis (April 2011). "Cryptogenic and Secondary Organizing Pneumonia". Chest. 139 (4): 893–900. doi:10.1378/chest.10-0883. PMID 20724743.

- Radswiki; et al. "Reversed halo sign (lungs)". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2018-01-02.

- Zare Mehrjardi, Mohammad; Kahkouee, Shahram; Pourabdollah, Mihan (March 2017). "Radio-pathological correlation of organizing pneumonia (OP): a pictorial review". The British Journal of Radiology. 90 (1071): 20160723. doi:10.1259/bjr.20160723. ISSN 1748-880X. PMC 5601538. PMID 28106480.

- Oikonomou, A; Hansell, DM (2001). "Organizing pneumonia: the many morphological faces". European Radiology. 12 (6): 1486–96. doi:10.1007/s00330-001-1211-3. PMID 12042959. S2CID 10180778.

- Yoshida, K; Nakajima, M; Niki, Y; Matsushima, T (2001). "Atelectasis of the right lower lobe in association with bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia". Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi = the Journal of the Japanese Respiratory Society. 39 (4): 260–5. PMID 11481825.

- Oymak FS, Demirbaş HM, Mavili E, et al. (2005). "Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Clinical and roentgenological features in 26 cases". Respiration. 72 (3): 254–62. doi:10.1159/000085366. PMID 15942294. S2CID 71769382.

External links

- "Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias". Merck Manual Professional. May 2008.