Cryptographic hash function

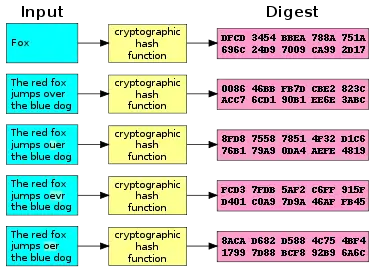

A cryptographic hash function (CHF) is a hash algorithm (a map of an arbitrary binary string to a binary string with a fixed size of bits) that has special properties desirable for a cryptographic application:[1]

- the probability of a particular -bit output result (hash value) for a random input string ("message") is (as for any good hash), so the hash value can be used as a representative of the message;

- finding an input string that matches a given hash value (a pre-image) is unfeasible, assuming all input strings are equally likely. The resistance to such search is quantified as security strength, a cryptographic hash with bits of hash value is expected to have a preimage resistance strength of bits. However, if the space of possible inputs is significantly smaller than , or if it can be ordered by likelihood, then the hash value can serve as an oracle, allowing efficient search of the limited or ordered input space. A common example is the use of a standard fast hash function to obscure user passwords in storage. If an attacker can obtain the hashes of a set of passwords, they can test each hash value against lists of common passwords and all possible combinations of short passwords and typically recover a large fraction of the passwords themselves. See #Attacks on hashed passwords.

- A second preimage resistance strength, with the same expectations, refers to a similar problem of finding a second message that matches the given hash value when one message is already known;

- finding any pair of different messages that yield the same hash value (a collision) is also unfeasible, a cryptographic hash is expected to have a collision resistance strength of bits (lower due to the birthday paradox).

| Secure Hash Algorithms | |

|---|---|

| Concepts | |

| hash functions, SHA, DSA | |

| Main standards | |

| SHA-0, SHA-1, SHA-2, SHA-3 | |

Cryptographic hash functions have many information-security applications, notably in digital signatures, message authentication codes (MACs), and other forms of authentication. They can also be used as ordinary hash functions, to index data in hash tables, for fingerprinting, to detect duplicate data or uniquely identify files, and as checksums to detect accidental data corruption. Indeed, in information-security contexts, cryptographic hash values are sometimes called (digital) fingerprints, checksums, or just hash values, even though all these terms stand for more general functions with rather different properties and purposes.[2]

Non-cryptographic hash functions are used in hash tables and to detect accidental errors, their construction frequently provides no resistance to a deliberate attack. For example, a denial-of-service attack on hash tables is possible if the collisions are easy to find, like in the case of linear cyclic redundancy check (CRC) functions.[3]

Properties

Most cryptographic hash functions are designed to take a string of any length as input and produce a fixed-length hash value.

A cryptographic hash function must be able to withstand all known types of cryptanalytic attack. In theoretical cryptography, the security level of a cryptographic hash function has been defined using the following properties:

- Pre-image resistance

- Given a hash value h, it should be difficult to find any message m such that h = hash(m). This concept is related to that of a one-way function. Functions that lack this property are vulnerable to preimage attacks.

- Second pre-image resistance

- Given an input m1, it should be difficult to find a different input m2 such that hash(m1) = hash(m2). This property is sometimes referred to as weak collision resistance. Functions that lack this property are vulnerable to second-preimage attacks.

- Collision resistance

- It should be difficult to find two different messages m1 and m2 such that hash(m1) = hash(m2). Such a pair is called a cryptographic hash collision. This property is sometimes referred to as strong collision resistance. It requires a hash value at least twice as long as that required for pre-image resistance; otherwise collisions may be found by a birthday attack.[4]

Collision resistance implies second pre-image resistance but does not imply pre-image resistance.[5] The weaker assumption is always preferred in theoretical cryptography, but in practice, a hash-function which is only second pre-image resistant is considered insecure and is therefore not recommended for real applications.

Informally, these properties mean that a malicious adversary cannot replace or modify the input data without changing its digest. Thus, if two strings have the same digest, one can be very confident that they are identical. Second pre-image resistance prevents an attacker from crafting a document with the same hash as a document the attacker cannot control. Collision resistance prevents an attacker from creating two distinct documents with the same hash.

A function meeting these criteria may still have undesirable properties. Currently, popular cryptographic hash functions are vulnerable to length-extension attacks: given hash(m) and len(m) but not m, by choosing a suitable m′ an attacker can calculate hash(m ∥ m′), where ∥ denotes concatenation.[6] This property can be used to break naive authentication schemes based on hash functions. The HMAC construction works around these problems.

In practice, collision resistance is insufficient for many practical uses. In addition to collision resistance, it should be impossible for an adversary to find two messages with substantially similar digests; or to infer any useful information about the data, given only its digest. In particular, a hash function should behave as much as possible like a random function (often called a random oracle in proofs of security) while still being deterministic and efficiently computable. This rules out functions like the SWIFFT function, which can be rigorously proven to be collision-resistant assuming that certain problems on ideal lattices are computationally difficult, but, as a linear function, does not satisfy these additional properties.[7]

Checksum algorithms, such as CRC32 and other cyclic redundancy checks, are designed to meet much weaker requirements and are generally unsuitable as cryptographic hash functions. For example, a CRC was used for message integrity in the WEP encryption standard, but an attack was readily discovered, which exploited the linearity of the checksum.

Degree of difficulty

In cryptographic practice, "difficult" generally means "almost certainly beyond the reach of any adversary who must be prevented from breaking the system for as long as the security of the system is deemed important". The meaning of the term is therefore somewhat dependent on the application since the effort that a malicious agent may put into the task is usually proportional to their expected gain. However, since the needed effort usually multiplies with the digest length, even a thousand-fold advantage in processing power can be neutralized by adding a dozen bits to the latter.

For messages selected from a limited set of messages, for example passwords or other short messages, it can be feasible to invert a hash by trying all possible messages in the set. Because cryptographic hash functions are typically designed to be computed quickly, special key derivation functions that require greater computing resources have been developed that make such brute-force attacks more difficult.

In some theoretical analyses "difficult" has a specific mathematical meaning, such as "not solvable in asymptotic polynomial time". Such interpretations of difficulty are important in the study of provably secure cryptographic hash functions but do not usually have a strong connection to practical security. For example, an exponential-time algorithm can sometimes still be fast enough to make a feasible attack. Conversely, a polynomial-time algorithm (e.g., one that requires n20 steps for n-digit keys) may be too slow for any practical use.

Illustration

An illustration of the potential use of a cryptographic hash is as follows: Alice poses a tough math problem to Bob and claims that she has solved it. Bob would like to try it himself, but would yet like to be sure that Alice is not bluffing. Therefore, Alice writes down her solution, computes its hash, and tells Bob the hash value (whilst keeping the solution secret). Then, when Bob comes up with the solution himself a few days later, Alice can prove that she had the solution earlier by revealing it and having Bob hash it and check that it matches the hash value given to him before. (This is an example of a simple commitment scheme; in actual practice, Alice and Bob will often be computer programs, and the secret would be something less easily spoofed than a claimed puzzle solution.)

Applications

Verifying the integrity of messages and files

An important application of secure hashes is the verification of message integrity. Comparing message digests (hash digests over the message) calculated before, and after, transmission can determine whether any changes have been made to the message or file.

MD5, SHA-1, or SHA-2 hash digests are sometimes published on websites or forums to allow verification of integrity for downloaded files,[8] including files retrieved using file sharing such as mirroring. This practice establishes a chain of trust as long as the hashes are posted on a trusted site – usually the originating site – authenticated by HTTPS. Using a cryptographic hash and a chain of trust detects malicious changes to the file. Non-cryptographic error-detecting codes such as cyclic redundancy checks only prevent against non-malicious alterations of the file, since an intentional spoof can readily be crafted to have the colliding code value.

Signature generation and verification

Almost all digital signature schemes require a cryptographic hash to be calculated over the message. This allows the signature calculation to be performed on the relatively small, statically sized hash digest. The message is considered authentic if the signature verification succeeds given the signature and recalculated hash digest over the message. So the message integrity property of the cryptographic hash is used to create secure and efficient digital signature schemes.

Password verification

Password verification commonly relies on cryptographic hashes. Storing all user passwords as cleartext can result in a massive security breach if the password file is compromised. One way to reduce this danger is to only store the hash digest of each password. To authenticate a user, the password presented by the user is hashed and compared with the stored hash. A password reset method is required when password hashing is performed; original passwords cannot be recalculated from the stored hash value.

However, use of standard cryptographic hash functions, such as the SHA series, is no longer considered safe for password storage.[9]: 5.1.1.2 These algorithms are designed to be computed quickly, so if the hashed values are compromised, it is possible to try guessed passwords at high rates. Common graphics processing units can try billions of possible passwords each second. Password hash functions that perform key stretching – such as PBKDF2, scrypt or Argon2 – commonly use repeated invocations of a cryptographic hash to increase the time (and in some cases computer memory) required to perform brute-force attacks on stored password hash digests. See #Attacks on hashed passwords

A password hash also requires the use of a large random, non-secret salt value which can be stored with the password hash. The salt is hashed with the password, altering the password hash mapping for each password, thereby making it infeasible for an adversary to store tables of precomputed hash values to which the password hash digest can be compared or to test a large number of purloined hash values in parallel.

Proof-of-work

A proof-of-work system (or protocol, or function) is an economic measure to deter denial-of-service attacks and other service abuses such as spam on a network by requiring some work from the service requester, usually meaning processing time by a computer. A key feature of these schemes is their asymmetry: the work must be moderately hard (but feasible) on the requester side but easy to check for the service provider. One popular system – used in Bitcoin mining and Hashcash – uses partial hash inversions to prove that work was done, to unlock a mining reward in Bitcoin, and as a good-will token to send an e-mail in Hashcash. The sender is required to find a message whose hash value begins with a number of zero bits. The average work that the sender needs to perform in order to find a valid message is exponential in the number of zero bits required in the hash value, while the recipient can verify the validity of the message by executing a single hash function. For instance, in Hashcash, a sender is asked to generate a header whose 160-bit SHA-1 hash value has the first 20 bits as zeros. The sender will, on average, have to try 219 times to find a valid header.

File or data identifier

A message digest can also serve as a means of reliably identifying a file; several source code management systems, including Git, Mercurial and Monotone, use the sha1sum of various types of content (file content, directory trees, ancestry information, etc.) to uniquely identify them. Hashes are used to identify files on peer-to-peer filesharing networks. For example, in an ed2k link, an MD4-variant hash is combined with the file size, providing sufficient information for locating file sources, downloading the file, and verifying its contents. Magnet links are another example. Such file hashes are often the top hash of a hash list or a hash tree which allows for additional benefits.

One of the main applications of a hash function is to allow the fast look-up of data in a hash table. Being hash functions of a particular kind, cryptographic hash functions lend themselves well to this application too.

However, compared with standard hash functions, cryptographic hash functions tend to be much more expensive computationally. For this reason, they tend to be used in contexts where it is necessary for users to protect themselves against the possibility of forgery (the creation of data with the same digest as the expected data) by potentially malicious participants.

Content-addressable storage

Content-addressable storage (CAS), also referred to as content-addressed storage or fixed-content storage, is a way to store information so it can be retrieved based on its content, not its name or location. It has been used for high-speed storage and retrieval of fixed content, such as documents stored for compliance with government regulations. Content-addressable storage is similar to content-addressable memory.

CAS systems work by passing the content of the file through a cryptographic hash function to generate a unique key, the "content address". The file system's directory stores these addresses and a pointer to the physical storage of the content. Because an attempt to store the same file will generate the same key, CAS systems ensure that the files within them are unique, and because changing the file will result in a new key, CAS systems provide assurance that the file is unchanged.

CAS became a significant market during the 2000s, especially after the introduction of the 2002 Sarbanes–Oxley Act which required the storage of enormous numbers of documents for long periods and retrieved only rarely. Ever-increasing performance of traditional file systems and new software systems have eroded the value of legacy CAS systems, which have become increasingly rare after roughly 2018. However, the principles of content addressability continue to be of great interest to computer scientists, and form the core of numerous emerging technologies, such as peer-to-peer file sharing, cryptocurrencies, and distributed computing.Hash functions based on block ciphers

There are several methods to use a block cipher to build a cryptographic hash function, specifically a one-way compression function.

The methods resemble the block cipher modes of operation usually used for encryption. Many well-known hash functions, including MD4, MD5, SHA-1 and SHA-2, are built from block-cipher-like components designed for the purpose, with feedback to ensure that the resulting function is not invertible. SHA-3 finalists included functions with block-cipher-like components (e.g., Skein, BLAKE) though the function finally selected, Keccak, was built on a cryptographic sponge instead.

A standard block cipher such as AES can be used in place of these custom block ciphers; that might be useful when an embedded system needs to implement both encryption and hashing with minimal code size or hardware area. However, that approach can have costs in efficiency and security. The ciphers in hash functions are built for hashing: they use large keys and blocks, can efficiently change keys every block, and have been designed and vetted for resistance to related-key attacks. General-purpose ciphers tend to have different design goals. In particular, AES has key and block sizes that make it nontrivial to use to generate long hash values; AES encryption becomes less efficient when the key changes each block; and related-key attacks make it potentially less secure for use in a hash function than for encryption.

Hash function design

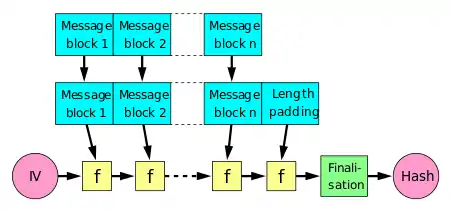

Merkle–Damgård construction

A hash function must be able to process an arbitrary-length message into a fixed-length output. This can be achieved by breaking the input up into a series of equally sized blocks, and operating on them in sequence using a one-way compression function. The compression function can either be specially designed for hashing or be built from a block cipher. A hash function built with the Merkle–Damgård construction is as resistant to collisions as is its compression function; any collision for the full hash function can be traced back to a collision in the compression function.

The last block processed should also be unambiguously length padded; this is crucial to the security of this construction. This construction is called the Merkle–Damgård construction. Most common classical hash functions, including SHA-1 and MD5, take this form.

Wide pipe versus narrow pipe

A straightforward application of the Merkle–Damgård construction, where the size of hash output is equal to the internal state size (between each compression step), results in a narrow-pipe hash design. This design causes many inherent flaws, including length-extension, multicollisions,[10] long message attacks,[11] generate-and-paste attacks, and also cannot be parallelized. As a result, modern hash functions are built on wide-pipe constructions that have a larger internal state size – which range from tweaks of the Merkle–Damgård construction[10] to new constructions such as the sponge construction and HAIFA construction.[12] None of the entrants in the NIST hash function competition use a classical Merkle–Damgård construction.[13]

Meanwhile, truncating the output of a longer hash, such as used in SHA-512/256, also defeats many of these attacks.[14]

Use in building other cryptographic primitives

Hash functions can be used to build other cryptographic primitives. For these other primitives to be cryptographically secure, care must be taken to build them correctly.

Message authentication codes (MACs) (also called keyed hash functions) are often built from hash functions. HMAC is such a MAC.

Just as block ciphers can be used to build hash functions, hash functions can be used to build block ciphers. Luby-Rackoff constructions using hash functions can be provably secure if the underlying hash function is secure. Also, many hash functions (including SHA-1 and SHA-2) are built by using a special-purpose block cipher in a Davies–Meyer or other construction. That cipher can also be used in a conventional mode of operation, without the same security guarantees; for example, SHACAL, BEAR and LION.

Pseudorandom number generators (PRNGs) can be built using hash functions. This is done by combining a (secret) random seed with a counter and hashing it.

Some hash functions, such as Skein, Keccak, and RadioGatún, output an arbitrarily long stream and can be used as a stream cipher, and stream ciphers can also be built from fixed-length digest hash functions. Often this is done by first building a cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generator and then using its stream of random bytes as keystream. SEAL is a stream cipher that uses SHA-1 to generate internal tables, which are then used in a keystream generator more or less unrelated to the hash algorithm. SEAL is not guaranteed to be as strong (or weak) as SHA-1. Similarly, the key expansion of the HC-128 and HC-256 stream ciphers makes heavy use of the SHA-256 hash function.

Concatenation

Concatenating outputs from multiple hash functions provide collision resistance as good as the strongest of the algorithms included in the concatenated result. For example, older versions of Transport Layer Security (TLS) and Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) used concatenated MD5 and SHA-1 sums.[15][16] This ensures that a method to find collisions in one of the hash functions does not defeat data protected by both hash functions.

For Merkle–Damgård construction hash functions, the concatenated function is as collision-resistant as its strongest component, but not more collision-resistant. Antoine Joux observed that 2-collisions lead to n-collisions: if it is feasible for an attacker to find two messages with the same MD5 hash, then they can find as many additional messages with that same MD5 hash as they desire, with no greater difficulty.[17] Among those n messages with the same MD5 hash, there is likely to be a collision in SHA-1. The additional work needed to find the SHA-1 collision (beyond the exponential birthday search) requires only polynomial time.[18][19]

Cryptographic hash algorithms

There are many cryptographic hash algorithms; this section lists a few algorithms that are referenced relatively often. A more extensive list can be found on the page containing a comparison of cryptographic hash functions.

MD5

MD5 was designed by Ronald Rivest in 1991 to replace an earlier hash function, MD4, and was specified in 1992 as RFC 1321. Collisions against MD5 can be calculated within seconds which makes the algorithm unsuitable for most use cases where a cryptographic hash is required. MD5 produces a digest of 128 bits (16 bytes).

SHA-1

SHA-1 was developed as part of the U.S. Government's Capstone project. The original specification – now commonly called SHA-0 – of the algorithm was published in 1993 under the title Secure Hash Standard, FIPS PUB 180, by U.S. government standards agency NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology). It was withdrawn by the NSA shortly after publication and was superseded by the revised version, published in 1995 in FIPS PUB 180-1 and commonly designated SHA-1. Collisions against the full SHA-1 algorithm can be produced using the shattered attack and the hash function should be considered broken. SHA-1 produces a hash digest of 160 bits (20 bytes).

Documents may refer to SHA-1 as just "SHA", even though this may conflict with the other Secure Hash Algorithms such as SHA-0, SHA-2, and SHA-3.

RIPEMD-160

RIPEMD (RACE Integrity Primitives Evaluation Message Digest) is a family of cryptographic hash functions developed in Leuven, Belgium, by Hans Dobbertin, Antoon Bosselaers, and Bart Preneel at the COSIC research group at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, and first published in 1996. RIPEMD was based upon the design principles used in MD4 and is similar in performance to the more popular SHA-1. RIPEMD-160 has, however, not been broken. As the name implies, RIPEMD-160 produces a hash digest of 160 bits (20 bytes).

Whirlpool

Whirlpool is a cryptographic hash function designed by Vincent Rijmen and Paulo S. L. M. Barreto, who first described it in 2000. Whirlpool is based on a substantially modified version of the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). Whirlpool produces a hash digest of 512 bits (64 bytes).

SHA-2

SHA-2 (Secure Hash Algorithm 2) is a set of cryptographic hash functions designed by the United States National Security Agency (NSA), first published in 2001. They are built using the Merkle–Damgård structure, from a one-way compression function itself built using the Davies–Meyer structure from a (classified) specialized block cipher.

SHA-2 basically consists of two hash algorithms: SHA-256 and SHA-512. SHA-224 is a variant of SHA-256 with different starting values and truncated output. SHA-384 and the lesser-known SHA-512/224 and SHA-512/256 are all variants of SHA-512. SHA-512 is more secure than SHA-256 and is commonly faster than SHA-256 on 64-bit machines such as AMD64.

The output size in bits is given by the extension to the "SHA" name, so SHA-224 has an output size of 224 bits (28 bytes); SHA-256, 32 bytes; SHA-384, 48 bytes; and SHA-512, 64 bytes.

SHA-3

SHA-3 (Secure Hash Algorithm 3) was released by NIST on August 5, 2015. SHA-3 is a subset of the broader cryptographic primitive family Keccak. The Keccak algorithm is the work of Guido Bertoni, Joan Daemen, Michael Peeters, and Gilles Van Assche. Keccak is based on a sponge construction which can also be used to build other cryptographic primitives such as a stream cipher. SHA-3 provides the same output sizes as SHA-2: 224, 256, 384, and 512 bits.

Configurable output sizes can also be obtained using the SHAKE-128 and SHAKE-256 functions. Here the -128 and -256 extensions to the name imply the security strength of the function rather than the output size in bits.

BLAKE2

BLAKE2, an improved version of BLAKE, was announced on December 21, 2012. It was created by Jean-Philippe Aumasson, Samuel Neves, Zooko Wilcox-O'Hearn, and Christian Winnerlein with the goal of replacing the widely used but broken MD5 and SHA-1 algorithms. When run on 64-bit x64 and ARM architectures, BLAKE2b is faster than SHA-3, SHA-2, SHA-1, and MD5. Although BLAKE and BLAKE2 have not been standardized as SHA-3 has, BLAKE2 has been used in many protocols including the Argon2 password hash, for the high efficiency that it offers on modern CPUs. As BLAKE was a candidate for SHA-3, BLAKE and BLAKE2 both offer the same output sizes as SHA-3 – including a configurable output size.

BLAKE3

BLAKE3, an improved version of BLAKE2, was announced on January 9, 2020. It was created by Jack O'Connor, Jean-Philippe Aumasson, Samuel Neves, and Zooko Wilcox-O'Hearn. BLAKE3 is a single algorithm, in contrast to BLAKE and BLAKE2, which are algorithm families with multiple variants. The BLAKE3 compression function is closely based on that of BLAKE2s, with the biggest difference being that the number of rounds is reduced from 10 to 7. Internally, BLAKE3 is a Merkle tree, and it supports higher degrees of parallelism than BLAKE2.

Attacks on cryptographic hash algorithms

There is a long list of cryptographic hash functions but many have been found to be vulnerable and should not be used. For instance, NIST selected 51 hash functions[20] as candidates for round 1 of the SHA-3 hash competition, of which 10 were considered broken and 16 showed significant weaknesses and therefore did not make it to the next round; more information can be found on the main article about the NIST hash function competitions.

Even if a hash function has never been broken, a successful attack against a weakened variant may undermine the experts' confidence. For instance, in August 2004 collisions were found in several then-popular hash functions, including MD5.[21] These weaknesses called into question the security of stronger algorithms derived from the weak hash functions – in particular, SHA-1 (a strengthened version of SHA-0), RIPEMD-128, and RIPEMD-160 (both strengthened versions of RIPEMD).[22]

On August 12, 2004, Joux, Carribault, Lemuel, and Jalby announced a collision for the full SHA-0 algorithm.[17] Joux et al. accomplished this using a generalization of the Chabaud and Joux attack. They found that the collision had complexity 251 and took about 80,000 CPU hours on a supercomputer with 256 Itanium 2 processors – equivalent to 13 days of full-time use of the supercomputer.

In February 2005, an attack on SHA-1 was reported that would find collision in about 269 hashing operations, rather than the 280 expected for a 160-bit hash function. In August 2005, another attack on SHA-1 was reported that would find collisions in 263 operations. Other theoretical weaknesses of SHA-1 have been known:[23][24] and in February 2017 Google announced a collision in SHA-1.[25] Security researchers recommend that new applications can avoid these problems by using later members of the SHA family, such as SHA-2, or using techniques such as randomized hashing[26] that do not require collision resistance.

A successful, practical attack broke MD5 used within certificates for Transport Layer Security in 2008.[27]

Many cryptographic hashes are based on the Merkle–Damgård construction. All cryptographic hashes that directly use the full output of a Merkle–Damgård construction are vulnerable to length extension attacks. This makes the MD5, SHA-1, RIPEMD-160, Whirlpool, and the SHA-256 / SHA-512 hash algorithms all vulnerable to this specific attack. SHA-3, BLAKE2, BLAKE3, and the truncated SHA-2 variants are not vulnerable to this type of attack.

Attacks on hashed passwords

A common use of hashes is to store password authentication data. Rather than store the plaintext of user passwords, a controlled access system stores the hash of each user's password in a file or database. When someone requests access, the password they submit is hashed and compared with the stored value. If the database is stolen (an all too frequent occurrence[28]), the thief will only have the hash values, not the passwords.

However, most people choose passwords in predictable ways. Lists of common passwords are widely circulated and many passwords are short enough that all possible combinations can be tested if fast hashes are used.[29] The use of cryptographic salt prevents some attacks, such as building files of precomputing hash values, e.g. rainbow tables. But searches on the order of 100 billion tests per second are possible with high-end graphics processors, making direct attacks possible even with salt.[30] [31] The United States National Institute of Standards and Technology recommends storing passwords using special hashes called key derivation functions (KDFs) that have been created to slow brute force searches.[9]: 5.1.1.2 Slow hashes include pbkdf2, bcrypt, scrypt, argon2, Balloon and some recent modes of Unix crypt. For KDFs that perform multiple hashes to slow execution, NIST recommends an iteration count of 10,000 or more.[9]: 5.1.1.2

See also

References

Citations

- Menezes, van Oorschot & Vanstone 2018, p. 33.

- Schneier, Bruce. "Cryptanalysis of MD5 and SHA: Time for a New Standard". Computerworld. Archived from the original on 2016-03-16. Retrieved 2016-04-20.

Much more than encryption algorithms, one-way hash functions are the workhorses of modern cryptography.

- Aumasson 2017, p. 106.

- Katz & Lindell 2014, pp. 155–157, 190, 232.

- Rogaway & Shrimpton 2004, in Sec. 5. Implications.

- Duong, Thai; Rizzo, Juliano. "Flickr's API Signature Forgery Vulnerability".

- Lyubashevsky et al. 2008, pp. 54–72.

- Perrin, Chad (December 5, 2007). "Use MD5 hashes to verify software downloads". TechRepublic. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- Grassi Paul A. (June 2017). SP 800-63B-3 – Digital Identity Guidelines, Authentication and Lifecycle Management. NIST. doi:10.6028/NIST.SP.800-63b.

- Lucks, Stefan (2004). "Design Principles for Iterated Hash Functions". Cryptology ePrint Archive. Report 2004/253.

- Kelsey & Schneier 2005, pp. 474–490.

- Biham, Eli; Dunkelman, Orr (24 August 2006). A Framework for Iterative Hash Functions – HAIFA. Second NIST Cryptographic Hash Workshop. Cryptology ePrint Archive. Report 2007/278.

- Nandi & Paul 2010.

- Dobraunig, Christoph; Eichlseder, Maria; Mendel, Florian (February 2015). Security Evaluation of SHA-224, SHA-512/224, and SHA-512/256 (PDF) (Report).

- Mendel et al., p. 145:Concatenating ... is often used by implementors to "hedge bets" on hash functions. A combiner of the form MD5

- Harnik et al. 2005, p. 99: the concatenation of hash functions as suggested in the TLS... is guaranteed to be as secure as the candidate that remains secure.

- Joux 2004.

- Finney, Hal (August 20, 2004). "More Problems with Hash Functions". The Cryptography Mailing List. Archived from the original on April 9, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2016.

- Hoch & Shamir 2008, pp. 616–630.

- Andrew Regenscheid, Ray Perlner, Shu-Jen Chang, John Kelsey, Mridul Nandi, Souradyuti Paul, Status Report on the First Round of the SHA-3 Cryptographic Hash Algorithm Competition

- XiaoyunWang, Dengguo Feng, Xuejia Lai, Hongbo Yu, Collisions for Hash Functions MD4, MD5, HAVAL-128, and RIPEMD

- Alshaikhli, Imad Fakhri; AlAhmad, Mohammad Abdulateef (2015), "Cryptographic Hash Function", Handbook of Research on Threat Detection and Countermeasures in Network Security, IGI Global, pp. 80–94, doi:10.4018/978-1-4666-6583-5.ch006, ISBN 978-1-4666-6583-5

- Xiaoyun Wang, Yiqun Lisa Yin, and Hongbo Yu, Finding Collisions in the Full SHA-1

- Bruce Schneier, Cryptanalysis of SHA-1 (summarizes Wang et al. results and their implications)

- Fox-Brewster, Thomas. "Google Just 'Shattered' An Old Crypto Algorithm – Here's Why That's Big For Web Security". Forbes. Retrieved 2017-02-24.

- Shai Halevi and Hugo Krawczyk, Randomized Hashing and Digital Signatures

- Alexander Sotirov, Marc Stevens, Jacob Appelbaum, Arjen Lenstra, David Molnar, Dag Arne Osvik, Benne de Weger, MD5 considered harmful today: Creating a rogue CA certificate, accessed March 29, 2009.

- Swinhoe, Dan (April 17, 2020). "The 15 biggest data breaches of the 21st century". CSO Magazine.

- Goodin, Dan (2012-12-10). "25-GPU cluster cracks every standard Windows password in <6 hours". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- Claburn, Thomas (February 14, 2019). "Use an 8-char Windows NTLM password? Don't. Every single one can be cracked in under 2.5hrs". www.theregister.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- "Mind-blowing GPU performance". Improsec. January 3, 2020.

Sources

- Harnik, Danny; Kilian, Joe; Naor, Moni; Reingold, Omer; Rosen, Alon (2005). "On Robust Combiners for Oblivious Transfer and Other Primitives". Advances in Cryptology – EUROCRYPT 2005. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3494. pp. 96–113. doi:10.1007/11426639_6. ISBN 978-3-540-25910-7. ISSN 0302-9743.

- Hoch, Jonathan J.; Shamir, Adi (2008). "On the Strength of the Concatenated Hash Combiner When All the Hash Functions Are Weak". Automata, Languages and Programming. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 5126. pp. 616–630. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-70583-3_50. ISBN 978-3-540-70582-6. ISSN 0302-9743.

- Joux, Antoine (2004). "Multicollisions in Iterated Hash Functions. Application to Cascaded Constructions". Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO 2004. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3152. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 306–316. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-28628-8_19. ISBN 978-3-540-22668-0. ISSN 0302-9743.

- Kelsey, John; Schneier, Bruce (2005). "Second Preimages on n-Bit Hash Functions for Much Less than 2 n Work". Advances in Cryptology – EUROCRYPT 2005. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3494. pp. 474–490. doi:10.1007/11426639_28. ISBN 978-3-540-25910-7. ISSN 0302-9743.

- Katz, Jonathan; Lindell, Yehuda (2014). Introduction to Modern Cryptography (2nd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4665-7026-9.

- Lyubashevsky, Vadim; Micciancio, Daniele; Peikert, Chris; Rosen, Alon (2008). "SWIFFT: A Modest Proposal for FFT Hashing". Fast Software Encryption. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 5086. pp. 54–72. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-71039-4_4. ISBN 978-3-540-71038-7. ISSN 0302-9743.

- Mendel, Florian; Rechberger, Christian; Schläffer, Martin (2009). "MD5 Is Weaker Than Weak: Attacks on Concatenated Combiners". Advances in Cryptology – ASIACRYPT 2009. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 5912. pp. 144–161. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-10366-7_9. ISBN 978-3-642-10365-0. ISSN 0302-9743.

- Nandi, Mridul; Paul, Souradyuti (2010). "Speeding Up the Wide-Pipe: Secure and Fast Hashing". Progress in Cryptology - INDOCRYPT 2010. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 6498. pp. 144–162. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-17401-8_12. ISBN 978-3-642-17400-1. ISSN 0302-9743.

- Rogaway, P.; Shrimpton, T. (2004). "Cryptographic Hash-Function Basics: Definitions, Implications, and Separations for Preimage Resistance, Second-Preimage Resistance, and Collision Resistance". In Roy, B.; Mier, W. (eds.). Fast Software Encryption: 11th International Workshop, FSE 2004. Vol. 3017. Lecture Notes in Computer Science: Springer. pp. 371–388. ISBN 3-540-22171-9.

- Menezes, Alfred J.; van Oorschot, Paul C.; Vanstone, Scott A. (7 December 2018). "Hash functions". Handbook of Applied Cryptography. CRC Press. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-0-429-88132-9.

- Aumasson, Jean-Philippe (6 November 2017). Serious Cryptography: A Practical Introduction to Modern Encryption. No Starch Press. ISBN 978-1-59327-826-7. OCLC 1012843116.

External links

- Paar, Christof; Pelzl, Jan (2009). "11: Hash Functions". Understanding Cryptography, A Textbook for Students and Practitioners. Springer. Archived from the original on 2012-12-08. (companion web site contains online cryptography course that covers hash functions)

- "The ECRYPT Hash Function Website".

- Buldas, A. (2011). "Series of mini-lectures about cryptographic hash functions". Archived from the original on 2012-12-06.

- Open source python based application with GUI used to verify downloads.