Csángós

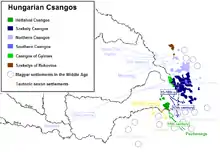

The Csángós (Hungarian: Csángók; Romanian: Ceangăi) are ethnic Hungarians of Roman Catholic faith living mostly in the Romanian region of Moldavia, especially in Bacău County. The region where the Csángós live in Moldavia is known as Csángó Land. Their traditional language, Csángó, an old Hungarian dialect, is currently used by only a minority of the Csángó population group.[6]

Csángók | |

|---|---|

Flag adopted by the Csángó Council[1] | |

| Total population | |

| 1,536 (self-declared, 2011 census)[2] 6,471 Hungarians in Moldavia[3] (4,208 in Bacău county, 2011 census)[4] 60,000–70,000 Csángó speakers (2001 estimate)[5] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Romania (mostly Moldavia, especially Csángó Land), Hungary (Tolna) | |

| Languages | |

| Romanian (most ethnic Csángós are monolingual Romanian speakers)[6] and Csángó, an old dialect of Hungarian[7][8] | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholic (majority) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Hungarians, Székelys, Romanians |

Some Csángós also live in Transylvania (around the Ghimeș-Palanca Pass and in the so-called Seven Csángó Villages)[9] and in the village of Oituz in Northern Dobruja.[10]

Etymology

It has been suggested that the name Csángó is the present participle of a Hungarian verb csángál meaning "wander, as if going away"; purportedly a reference to sibilation, in the pronunciation of some Hungarian consonants by Csángó people.[11][12][13]

Alternative explanations include the Hungarian word elcsángált, meaning "wandered away", or the phrase csángatta a harangot "ring the bell".

The Finnish researcher Yrjö Wichmann believed that probably the name of ceangău (csángó) did not come from a certain Hungarian tribe, but they were called those Transylvanian Szeklers who moved away from their comrades and settled in areas inhabited by Romanians, where they were, both materially and ideologically influenced by them and even Romanized to a certain level.[14] Ion Podea in the "Monograph of Brașov County" of 1938 mentioned that the ethnonym derives from the verb csángodni or ecsángodni and means "to leave someone or something, to alienate someone or something that has left you". This was used by the Szeklers in the case of other Romanized Szeklers from the Ciuc area.[15]

In some Hungarian dialects (the one from Transylvanian Plain and the Upper Tisza) "csángó", "cángó" means "wanderer".[16] In connection with this etymological interpretation, the linguist Szilágyi N. Sándor made an analogy between the verb "to wander" with the ethnonyms "kabars" and "khazars", which means the same thing.[17]

According to the "Dictionary of the Hungarian Language", 1862; The etymological dictionary of the Hungarian language , Budapest 1967; The historical dictionary of the Hungarian lexicon from Transylvania , Bucharest, 1978; The Explanatory Dictionary of the Hungarian Language , Hungarian Academy Publishing House, Budapest, 1972; The new dictionary of regionalisms , Hungarian Academy Publishing House, Budapest, 1979, the terms "csangó", "csángó" are translated in "walker", "a person who changes his place".

The historian Nicolae Iorga stated that the term comes from șalgăi (șálgó,[18] with the variants derived from the Hungarian sóvágó meaning "salt cutter"[19]), name given to the Szekler workers at Târgu Ocna mine.[18]

A theory of the historian Antal Horger relates that the ceangău comes from czammog, which refers to a shepherd who walks with the bludgeon after the herds. Another hypothesis of Bernát Munkácsi explains that the term comes from the verb csángani which in Ciuc County means to mix; csángadik.[20]

Origins

The Hungarian and the international literature in this subject unanimously agree that the Csángós are of Hungarian origin, but there are also small assimilated elements of Romanian, German, Polish, Italian and Gypsy origin.[21]

Hungarian origins include a mixture of Turkic (Cumans, Pannonian Avars, Khazars, Pechenegs, Székelys), original Hungarian, German and Alan populations.[22][23][24]

The Csángós had historically been a rural and agricultural people, raising stock like sheep and cows and farmed crops such as corn, potatoes, and hemp. They were also often called for military service, protecting the Eastern borders of the Kingdom of Hungary in the Middle Ages.[25] Before the Communist era and the collectivization efforts, the Csángós were structured in a traditional society until the introduction of civil code. Village elders were well respected and could be pointed out by their traditionally long hair and beards. Notably, some Csángós also participated in the 1907 Romanian Peasants' Revolt and fought on behalf of Romania in both world wars.[26]

Genetics

A study estimating possible Inner Asian admixture among nearly 500 Hungarians based on paternal lineages only, estimated it at 5.1% in Hungary, at 7.4% in Székelys and at 6.3% at Csángós.[27]

Csángós from Moldavia

Family from Săbăoani

Family from Săbăoani.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Săbăoani

Săbăoani

Csángós from Transylvania

Csángós from Săcele (Burzenland)

Csángós from Săcele (Burzenland) Csángó group from Săcele

Csángó group from Săcele Csángó family from Săcele

Csángó family from Săcele Csángós from Săcele

Csángós from Săcele

Csángós from Ghimeș (Gyimes)

History, culture and identity

Middle Age sources

Perugia, 14 November 1234: Pope Gregory IX to Béla IV, king of Hungary

"In the Cuman bishopric – as we were informed – is living a people called Vallah and others, Hungarians and Germans as well, who came here from the Hungarian Kingdom."

Roman, 13 April 1562: Report of the Habsburg Agent, John Belsius, to the Emperor Ferdinand the First

"On the day of the 10th of April, Despot Vodă left Hîrlău (Horlo) to Tîrgul Frumos (Zeplak = Széplak) finally on the 12th to the fortress of Roman (Románváros)" Despot Vodă ordered me to write these: Alexandru Moldoveanul forced all the nations, with no exceptions, to be baptized again and to follow the religion of the Moldavians, taking them away from their own religion, he appointed a bishop of the Saxons and the Hungarians, to rebuild the confiscated churches and to strengthen their souls in their beliefs, and his name is Ian Lusenius, and is Polish."

After 1562: Notes of the Humanist Johann Sommer about Saxons in Moldavia, from his work about the Life of Jacob-Despot, the Ruler of Moldavia

"Despot was unyielding in punishment, especially against the ones who don't respect the sanctity of marriage, -according to the habit of those people-: this habit was copied by the Hungarians and Saxons living here, in this country (Moldavia). He started to build a school in Cotnari, which is mostly inhabited by Hungarians and Saxons."

Iași, 14 January 1587: Bartolomeo Brutti's letter to Annibal de Capua

"These Franciscans are very few and they speak neither German, nor Hungarian, so they can't take spiritual care of these catholics, 15000 in number.

Roman 1588: The First Jesuit Mission in Moldavia: Written by Stanislaw Warszewicki

"In the whole region in 15 towns and in all the neighborhood villages there are Hungarians and Saxons, but most of them don't know how to read, don't even recognize the letters."[28]

Munich Codex: Hussite translation of the New Testament to Hungarian dated in the text in 1466 in Moldavia Hungarian edition (text original Old Hungarian with modernized script, foreword, introduction in modern Hungarian, dictionary in German and Hungarian).[29]

2001 Report of the Council of Europe

For centuries, the self-identity of the Csángós was based on the Roman Catholic religion and the Hungarian language spoken in the family. It is generally accepted by serious scholars (Hungarian but also Romanian) that the Csángós have a Hungarian origin, and that they arrived in Moldavia from the west. Some Romanian authors claim that the Csángós are in fact "Magyarised" Romanians from Transylvania. This theory has also to be dismissed; it is not conceivable that these "Romanians" could persist in using a "foreign" language after centuries of living in Romania surrounded by Romanians speaking Romanian. Whatever can be argued about the language of the Csángós there is no doubt that this is a form of Hungarian.– Csango minority culture in Romania, Doc. 9078 from 4 May 2001[7]

The Council of Europe has expressed its concerns about the situation of the Csángó minority culture,[8] and discussed that the Csángós speak an early form of Hungarian and are associated with ancient traditions, and a great diversity of folk art and culture, which is of exceptional value for Europe. The council also mentioned that (although not everybody agrees on this number) it is thought that between 60,000 and 70,000 people speak the Csángó Hungarian dialect. It has also expressed concerns that despite the provisions of the Romanian law on education, and repeated requests from parents there is no teaching of the Csángó language in the Csángó villages, and, as a consequence, very few Csángós are able to write in their mother tongue. The document also discussed that the Csángós make no political demands, but merely want to be recognized as a distinct culture and demand education and church services in the Csángó dialect.[7]

At the time of this report's release, the Vatican expressed hope that the Csángós would be able to celebrate Catholic masses in their liturgical language, Csángó.[30]

Comments of the government of Romania, dissenting opinion on behalf of the Romanian delegation

The situation of Csángó community may be understood by taking into consideration the results of 2002 census. 1,370 persons declared themselves Csángó.[31] Most of them live in Bacău County, Romania, and belong to the Roman Catholic Church. During the last years, some statements identified all Catholics in Bacău County (119.618 persons according to 2002 census) as Csángó. This identification is rejected by most of them, who did identify themselves as Romanians.[32]

The name Csángó appeared relatively recently, being used for the first time, in 1780 by Péter Zöld.[33] The name Csángó is used to describe two different ethnic groups:

- those concentrated in the county of Bacǎu (the southern group) and in the area surrounding the city of Roman (the northern group). We know for certain that these people are not Szeklers. They are Romanian in appearance, and the majority of them speak a Transylvanian dialect of Romanian and live according to Romanian traditions and customs. These characteristics suggest that they are Romanians from Transylvania who have joined the Romanian Catholic population of Moldavia.

- those of Szekler origin, most of whom settled in the valleys of the Trotuş and the Tazlǎu and, to a lesser extent, of the Siret. Their mother tongue is the same as that spoken by the Szeklers, and they live side by side with Romanians.[33]

Hungarian sources

Their music shows the characteristic features of Hungarian music and the words of their songs are mostly Hungarian, with some dialect differences.[34]

The anthem of the Csángós refers to Csángó Hungarians multiple times.[35][36]

The Csángós did not take part in the language reforms of the Age of Enlightenment, or the bourgeois transformation that created the modern consciousness of nationhood (cf. Halász 1992, Kósa 1998). They did not have a noble stratum or intelligentsia (cf. Kósa 1981) that could have fashioned their consciousness as Hungarians (Halász 1992: 11). They were "saved" (Kósa 1998: 339) from "assimilation" with the Romanians by virtue of their Roman Catholic religion, which distinguished them from the majority Greek Orthodox society.[37]

Romanian sources

Official Romanian censuses in Moldavia indicate the following:[38]

| Year | Hungarians in Moldavia |

|---|---|

| 1859 | 37,825 |

| 1899 | 24,276 |

| 1930 | 23,894 |

| 1992 | 3,098 |

Controversy

Hungarian sources

In 2001 the Romanian authorities banned the teaching of the Hungarian language in private houses in the village of Klézse, despite the recommendation of the Council of Europe.[39] From 1990, parents in Cleja, Pustiana and Lespezi requested several times that their children have the opportunity of learning the Hungarian language at school, either as an optional language, or as their native language, in 1-4 lessons a week. At best their petition was registered, but in most cases it was ignored. Seeing the possibility of organizing Hungarian courses outside school, they gave up the humiliating process of writing requests without results. The MCSMSZ maintains its standpoint according to which the community should claim their legal rights, but the population is not so determined. Leaders of the school inspectorate in Bacău County, as well as the authorities and church, declared at a meeting that they were opposed to the official instruction of Hungarian in Csángó villages. In their opinion the Csángós are of Romanian origin, and sporadic requests for teaching Hungarian at schools reflect not a real parental demand, but Hungarian nationalist ambitions.[40]

In the village of Arini (Magyarfalu in Hungarian) the village mayor and the Romanian-only teachers of the state school, filed a complaint with the local police about the "unlawful teaching activities" of Gergely Csoma. Csoma teaches Hungarian as an extracurricular activity to the children of Arini. Following the complaint, the local police started what Csángó activists have described as an intimidation campaign among the mothers of those children who are studying their maternal language with the said teacher.[41]

In 2008 members of the European Parliament sent a petition to the European Commission regarding the obstruction of Hungarian language education and the alleged intimidation of Csángó-Hungarian pupils in Valea Mare (Nagypatak).[42] The leader of the High Commission on Minority Affairs responded to the petition of László Tőkés MEP in a written notice that they would warn Romania to secure education in the mother tongue for the Csángós of Moldavia.[42]

Romanian sources

According to the final report of the Presidential Commission for the Study of the Communist Dictatorship in Romania in 2006, the policy of assimilation of the communist regime had serious consequences on the situation of the Csángós in Moldavia. The report noted that the first attempts at forced assimilation of the Csángós date back to the interwar period, with the Catholic Church taking on an important role in this process. Facilitating the loss of the linguistic identity of the Csángós allowed the Catholic Church to stop their assimilation into the Orthodox Church, and as a result of these policies, the Csángós did not benefit from religious services and education in their mother tongue.[43]

Population

It is difficult to estimate the exact number of the Csángós because of the elusive nature and multiple factors (ethnicity, religion and language) of Csángó identity.

As far as ethnic identification is concerned, in the census of 2002, 4,317 declared themselves Hungarians and 796 declared themselves Csángó in Bacău County, reaching a total of 5,794 out of the county's total population of 706,623. The report of the Council of Europe estimates a Csángó population ranging from 20,000 to as many as 260,000, based in the total Catholic population in the area, which is a clear exaggeration as there also are Catholic ethnic Romanians.[7] One plausible explanation for this discrepancy is that many Csángó hide or disguise their true ethnicity.

The Council of Europe had in 2001 estimates that put the total number of Csángó-speaking people between 60,000 and 70,000.[8]

According to the most recent research executed between 2008 and 2010 by Vilmos Tánczos, famous Hungarian folklorist, there has been a sharp decline in the total number of Csángó-speaking people in Eastern Romania. Tánczos set their number to roughly 43,000 people. Moreover, he found out that the most archaic version of Csángó language, the Northern Csángó was known and regularly used by only some 4,000 people, exclusively the older generation above the age of 50. It can be said, therefore, that the Csángó Hungarian dialect is in high risk of extinction. In fact, when applying the UNESCO Framework to measure language vitality, this dialect fits the category of "Severely Endangered".[44]

See also

References

- Székely, Blanka (25 July 2019). "New flag and coat of arms fuels Csango national identity". Transylvania Now.

- "Populația stabilă după etnie – județe, municipii, orașe, comune". Institutul Național de Statistică.

- "Center for Documentation and Information on Minorities in Europe – Southeast Europe (CEDIMSE-SE) : Minorities in Southeast Europe" (PDF). Edrc.ro. Retrieved 2013-12-06.

- https://bacau.insse.ro/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/RPL_2011_Structura_demografica_etnica_confesionala.pdf

- "Csango minority culture in Romania". December 17, 2005. Archived from the original on 2005-12-17.

- Klára Sándor (January 2000). "National feeling or responsibility: The case of the Csángó language revitalization" (PDF). Multilingua.

- "Csango minority culture in Romania". Committee on Culture, Science and Education. Council of Europe. 2001-05-04. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- "Recommendation 1521 (2001) — Csango minority culture in Romania". Parliamentary Assembly. Council of Europe. Archived from the original on 2005-12-17.

- Antal, Aubert; János, Csapó (2006). "A Kárpát-medence magyar vonatkozású etnikai-történeti tájegységei" (PDF) (in Hungarian). Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences of the University of Pécs: 1–28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Iancu, Mariana (25 April 2018). "Fascinanta poveste a ceangăilor care au ridicat un sat în pustiul dobrogean stăpânit de șerpi: "Veneau coloniști și ne furau tot, până și lanțul de la fântână"". Adevărul (in Romanian).

- Alexandru Ciorănescu, Dicţionarul etimologic român, Universidad de la Laguna, Tenerife, 1958–1966 ceangău

- Erdmann D. Beynon, "Isolated Racial Groups of Hungary", Geographical Review, Vol. 17, No. 4 (Oct., 1927), pp. 604

- Anna Fenyvesi (2005). Hungarian Language Contact Outside Hungary: Studies on Hungarian as a Minority Language. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-58811-630-7.

- Ștefan Casapu; Plaiuri Săcelene, Asociația Cultural-Sportivă „Izvorul” Săcele, Anul XXVII (Serie nouă), Trimestrul III, 2014, Nr. 81, pag. 6

- Ion Podea; Monografia județului Brașov, Vol. I, Institutul de Arte Grafice "Astra", Brașov, 1938, p. 50

- Új Magyar Tájszótár – Noul Dicționar de Regionalisme – articolul „csángó”

- Sándor N. Szilágyi; Amit még nem mondtak el a csángó névről in A Hét. X, 1979. No. 24, June 15, pag. 10

- Nicolae Iorga; Privilegiile șangăilor de la Târgu Ocna, Librăriile Socec & Comp. și C. Sfetea București, 1915, pag. 3/247

- Vilmos Tánczos, „Vreau să fiu român!” Identitatea lingvistică și religioasă a ceangăilor din Moldova, Editura Institutului pentru Studierea Problemelor Minorităților Naționale, 2018, ISBN 978 606 8377 55 1, p. 138

- Iosf Petru M Pal; Originea catolicilor din Moldova și Franciscanii păstorii lor de veacuri, Tipografia Serafica Săbăoani, Roman, 1941, pag. 96

- Vilmos Tánczos, Csángós in Moldavia, published in Magyar nemzeti kisebbségek Kelet-Közép-Európában ("Hungarian National Minorities in East-Central Europe"), Magyar Kisebbség, No. 1-2, 1997. (III), p. 1

- Robin Baker; On the Origin of the Moldavian Csángós, The Slavonic and East European Review, vol. 75, no. 4, 1997, UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London, pp. 658-680

- Guglielmino, C. R.; Silvestri, A. De; Beres, J. (2000). "Probable ancestors of Hungarian ethnic groups: an admixture analysis". Annals of Human Genetics. 64 (2): 145–159. doi:10.1046/j.1469-1809.2000.6420145.x. ISSN 1469-1809. PMID 11246468. S2CID 23742103.

- Vilmos Tánczos, Csángós in Moldavia, published in Magyar nemzeti kisebbségek Kelet-Közép-Európában ("Hungarian National Minorities in East-Central Europe"), Magyar Kisebbség, No. 1-2, 1997 (III)

- "The Csángós: A Unique Hungarian Community Living in Romania". Hungarianconservative.com/. 11 June 2023.

- Davis, R. Chris (2019). Hungarian Religion Romanian Blood (1st ed.). Wisconsin, USA: The University of Wisconsin Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-299-31640-2.

- András Bíró; Tibor Fehér; Gusztáv Bárány; Horolma Pamjav (15 November 2014). "Testing Central and Inner Asian admixture among contemporary Hungarians". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 15: 121–126. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2014.11.007. PMID 25468443.

- Archived October 30, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Király, László; Szabó T., Ádám (1985). A Müncheni Kódex négy evangéliuma (1466): A négy evangélium szövege és szótára. ISBN 9789630735346 – via Antikvarium.hu.

- "Csángó anyanyelvű oktatás". Népszabadság (in Hungarian). 2001-11-14. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- Archived March 2, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "Comments of the government of Romania on the second opinion of the Advisory Committee on the implementation of the framework convention for the protection of national minorities in Romania" (PDF). Government of Romania. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2009. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- "Appendix 2 — Dissenting opinion presented by Mr Prisǎcaru on behalf of the Romanian delegation". Delegation from Romania. Council of Europe. 2001-05-04. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- Palma Szirmai (1967). "A Csángó-Hungarian lament". Ethnomusicology. University of Illinois Press. 11 (3): 310–325. doi:10.2307/850268. JSTOR 850268.

- "Csángó Himnusz" (PDF). Székely Útkereső (cultural and literary magazine). 1998. p. 6.

- Horváth, Dezső (1999). "Eleven csángó". Mivé lettél, csángómagyar?. Hungarian Electronic Library. ISBN 963-9144-32-0.

- Balázs Soross. ""Once it shall be but not yet" – Contributions to the complex reality of the identity of the Csángós of Moldavia reflected by a cultural anthropological case study". Archived from the original on 2008-02-06. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- Tánczos Vilmos. "A moldvai csángók lélekszámáról". Kia.hu. Retrieved 2013-12-06.

- "Betiltották a csángók magyaróráit" (in Hungarian). 20 November 2001.

- "The Moldavian Csángós want to learn Hungarian". Homepage of the Hungarian Csángós. Archived from the original on 2008-02-06. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- "Rumanian Atrocities Against the Csango Minority". Homepage of the Hungarian Csángós. Archived from the original on July 6, 2007.

- "The issue of Hungarian Education in Moldavia, Romania in front of European Parliament". The Association of the Csango Hungarians of Moldavia. 2008-03-06. Archived from the original on 2008-06-09. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- Vladimir Tismăneanu, "Raport final", Presidential Commission for the Study of the Communist Dictatorship in Romania, p. 537

- "Situation of the Csángó Dialect of Moldavia in Romania". www.academia.edu.

External links

- Situation of the Csángó dialect in Romania

- Homepage of the Hungarian Csángós

- "Dumitru Mărtinaș" Roman-Catholic Association

- Association of Csángó-Hungarians in Moldavia

- Ceangaii, the Roman Catholic from Moldavia

- Council of Europe Recommendation 1521 (2001) on the Csango minority culture in Romania

- Song of the Csangos — National Geographic Magazine

- (in Romanian) Fundaţia culturală Siret

- (in Romanian) Comunitatile catolice din Moldova

- Romanians Roman-Catholics Museum (csángó museum)