Finns

Finns or Finnish people (Finnish: suomalaiset, IPA: [ˈsuo̯mɑlɑi̯set]) are a Baltic Finnic[40] ethnic group native to Finland.[41]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 6–7 million[a] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Finland c. 4.7–5.1 million[1][2][3][4][b] Other significant population centers: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| United States | 653,222[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sweden | 156,045[6][c]–712,000[7][d] (including Tornedalians) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Canada | 143,645[8] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Russia | 127,600 (with all Karelians)[lower-alpha 1][9] 34,300 (with Ingrian Finns) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Australia | 7,939[10] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Norway | 15,000–60,000 (including Forest Finns and Kvens)[11][12] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Germany | 33,000 (2022)[13] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| United Kingdom | 15,000–30,000[14] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spain | 12,961 (in 2016)[15] (up to 40,000 part-year residents)[16] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Estonia | 8,260[17] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| France | 7,000[18] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Netherlands | 5,000[19] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Italy | 4,000[20] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Switzerland | 3,800[21] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brazil | 3,100[22] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Denmark | 3,000[23] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Belgium | 3,000[24] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Finnish and its dialects | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predominantly Lutheranism or irreligious, Eastern Orthodox minority[39] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sámi, Balts, and other Baltic Finns Especially Karelians, Forest Finns, Ingrian Finns, Kvens, and Tornedalians | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

a The total figure is merely a sum of all the referenced populations listed. b No official statistics are kept on ethnicity. However, statistics of the Finnish population according to first language and citizenship are documented and available. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Finland |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Mythology and Folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Sport |

Finns are traditionally divided into smaller regional groups that span several countries adjacent to Finland, both those who are native to these countries as well as those who have resettled. Some of these may be classified as separate ethnic groups, rather than subgroups of Finns. These include the Kvens and Forest Finns in Norway, the Tornedalians in Sweden, and the Ingrian Finns in Russia.

Finnish, the language spoken by Finns, is closely related to other Balto-Finnic languages, e.g. Estonian and Karelian. The Finnic languages are a subgroup of the larger Uralic family of languages, which also includes Hungarian. These languages are markedly different from most other languages spoken in Europe, which belong to the Indo-European family of languages. Native Finns can also be divided according to dialect into subgroups sometimes called heimo (lit. tribe), although such divisions have become less important due to internal migration.

Today, there are approximately 6–7 million ethnic Finns and their descendants worldwide, with the majority of them living in their native Finland and the surrounding countries, namely Sweden, Russia and Norway. An overseas Finnish diaspora has long been established in the countries of the Americas and Oceania, with the population of primarily immigrant background, namely Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Brazil, and the United States.

Subgroups

The Population Register Centre maintains information on the birthplace, citizenship and mother tongue of the people living in Finland, but does not specifically categorize any as Finns by ethnicity.[42]

Balto-Finnic peoples

The majority of people living in Finland consider Finnish to be their first language. According to Statistics Finland, of the country's total population of 5,503,297 at the end of 2016, 88.3% (or 4,857,795) considered Finnish to be their native language.[43] It is not known how many of the ethnic Finns living outside Finland speak Finnish as their first language.

In addition to the Finnish-speaking inhabitants of Finland, the Kvens (people of Finnish descent in Norway), the Tornedalians (people of Finnish descent in northernmost Sweden), and the Karelians in the Republic of Karelia and Evangelical Lutheran Ingrian Finns (both in the northwestern Russian Federation), as well as Finnish expatriates in various countries, are Baltic Finns.

Finns have been traditionally divided into sub-groups (heimot in Finnish) along regional, dialectical or ethnographical lines. These subgroups include the people of Finland Proper (varsinaissuomalaiset), Satakunta (satakuntalaiset), Tavastia (hämäläiset), Savonia (savolaiset), Karelia (karjalaiset) and Ostrobothnia (pohjalaiset). These sub-groups express regional self-identity with varying frequency and significance.

There are a number of distinct dialects (murre s. murteet pl. in Finnish) of the Finnish language spoken in Finland, although the exclusive use of the standard Finnish (yleiskieli)—both in its formal written (kirjakieli) and more casual spoken (puhekieli) form—in Finnish schools, in the media, and in popular culture, along with internal migration and urbanization, have considerably diminished the use of regional varieties, especially since the middle of the 20th century. Historically, there were three dialects: the South-Western (Lounaismurteet), Tavastian (Hämeen murre), and Karelian (Karjalan murre). These and neighboring languages mixed with each other in various ways as the population spread out, and evolved into the Southern Ostrobothnian (Etelä-Pohjanmaan murre), Central Ostrobothnian (Keski-Pohjanmaan murre), Northern Ostrobothnian (Pohjois-Pohjanmaan murre), Far-Northern (Peräpohjolan murre), Savonian (Savon murre), and South-Eastern (Kaakkois-Suomen murteet) aka South Karelian (Karjalan murre) dialects.

Sweden Finns

The Sweden Finns are either native to Sweden or have emigrated from Finland to Sweden. An estimated 450,000 first- or second-generation immigrants from Finland live in Sweden, of which approximately half speak Finnish. The majority moved from Finland to Sweden following the Second World War, contributing and taking advantage of the rapidly expanding Swedish economy. This emigration peaked in 1970 and has been declining since. There is also a native Finnish-speaking minority in Sweden, the Tornedalians in the border area in the extreme north of Sweden. The Finnish language has official status as one of five minority languages in Sweden, but only in the five northernmost municipalities in Sweden.

Other groups

The term Finns is also used for other Baltic Finns, including Izhorians in Ingria, Karelians in Karelia and Veps in the former Veps National Volost, all in Russia. Among these groups, the Karelians is the most populous one, followed by the Ingrians. According to a 2002 census, it was found that Ingrians also identify with Finnish ethnic identity, referring to themselves as Ingrian Finns.[44]

Terminology

The Finnish term for Finns is suomalaiset (sing. suomalainen).

It is a matter of debate how best to designate the Finnish-speakers of Sweden, all of whom have migrated to Sweden from Finland. Terms used include Sweden Finns and Finnish Swedes, with a distinction almost always made between more recent Finnish immigrants, most of whom have arrived after World War II, and Tornedalians, who have lived along what is now the Swedish-Finnish border since the 15th century.[45] The term "Finn" occasionally also has the meaning "a member of a people speaking Finnish or a Finnic language".

Etymology

Historical references to Northern Europe are scarce, and the names given to its peoples and geographic regions are obscure; therefore, the etymologies of the names are questionable. Such names as Fenni, Phinnoi, Finnum, and Skrithfinni / Scridefinnum appear in a few written texts starting from about two millennia ago in association with peoples located in a northern part of Europe, but the real meaning of these terms is debatable. It has been suggested that this non-Uralic ethnonym is of Germanic language origin and related to such words as finthan (Old High German) 'find', 'notice'; fanthian (Old High German) 'check', 'try'; and fendo (Old High German) and vende (Old Middle German) 'pedestrian', 'wanderer'.[46] Another etymological interpretation associates this ethnonym with fen in a more toponymical approach. Yet another theory postulates that the words Finn and Kven are cognates. The Icelandic Eddas and Norse sagas (11th to 14th centuries), some of the oldest written sources probably originating from the closest proximity, use words like finnr and finnas inconsistently. However, most of the time they seem to mean northern dwellers with a mobile life style. Current linguistic research supports the hypothesis of an etymological link between the Finnish and the Sami languages and other modern Uralic languages. It also supports the hypothesis of a common etymological origin of the toponyms Sápmi (Sami for Lapland) and Suomi (Finnish for Finland) and the Finnish and Sami names for the Finnish and Sami languages (suomi and saame). Current research has disproved older hypotheses about connections with the names Häme (Finnish for Tavastia)[46] and the proto-Baltic word *žeme / Slavic земля (zemlja) meaning 'land'.[46][47] This research also supports the earlier hypothesis that the designation Suomi started out as the designation for Southwestern Finland (Finland Proper, Varsinais-Suomi) and later for their language and later for the whole area of modern Finland. But it is not known how, why, and when this occurred. Petri Kallio had suggested that the name Suomi may bear even earlier Indo-European echoes with the original meaning of either "land" or "human",[48] but he has since disproved his hypothesis.[47]

The first known mention of Finns is in the Old English poem Widsith which was compiled in the 10th century, though its contents are believed to be older. Among the first written sources possibly designating western Finland as the land of Finns are also two rune stones. One of these is in Söderby, Sweden, with the inscription finlont (U 582), and the other is in Gotland, a Swedish island in the Baltic Sea, with the inscription finlandi (G 319 M) dating from the 11th century.[49]

History

Origins

As other Western Uralic and Baltic Finnic peoples, Finns originated between the Volga, Oka, and Kama rivers in what is now Russia. The genetic basis of future Finns also emerged in this area.[51] There have been at least two noticeable waves of migration to the west by the ancestors of Finns. They began to move upstream of the Dnieper and from there to the upper reaches of the Väinäjoki (Daugava), from where they eventually moved along the river towards the Baltic Sea in 1250–1000 years BC. The second wave of migration brought the main group of ancestors of Finns from the Baltic Sea to the southwest coast of Finland in the 8th century BC.[52][53]

During the 80–100 generations of the migration, Finnish language changed its form, although it retained its Finno-Ugric roots. Material culture also changed during the transition, although the Baltic Finnic culture that formed on the shores of the Baltic Sea constantly retained its roots in a way that distinguished it from its neighbors.[52][54]

Finnish material culture became independent of the wider Baltic Finnic culture in the 6th and 7th centuries, and by the turn of the 8th century the culture of metal objects that had prevailed in Finland had developed in its own way.[52][55] The same era can be considered to be broadly the date of the birth of the independent Finnish language, although its prehistory, like other Baltic Finnic languages, extends far into the past.[55]

Language

Just as uncertain are the possible mediators and the timelines for the development of the Uralic majority language of the Finns. On the basis of comparative linguistics, it has been suggested that the separation of the Finnic and the Sami languages took place during the 2nd millennium BC, and that the Proto-Uralic roots of the entire language group date from about the 6th to the 8th millennium BC. When the Uralic languages were first spoken in the area of contemporary Finland is debated. It is thought that Proto-Finnic (the proto-language of the Finnic languages) was not spoken in modern Finland, because the maximum divergence of the daughter languages occurs in modern-day Estonia. Therefore, Finnish was already a separate language when arriving in Finland. Furthermore, the traditional Finnish lexicon has a large number of words (about one-third) without a known etymology, hinting at the existence of a disappeared Paleo-European language; these include toponyms such as niemi "peninsula". Because the Finnish language itself reached a written form only in the 16th century, little primary data remains of early Finnish life. For example, the origins of such cultural icons as the sauna, and the kantele (an instrument of the zither family) have remained rather obscure.

Livelihood

Agriculture supplemented by fishing and hunting has been the traditional livelihood among Finns. Slash-and-burn agriculture was practiced in the forest-covered east by Eastern Finns up to the 19th century. Agriculture, along with the language, distinguishes Finns from the Sámi, who retained the hunter-gatherer lifestyle longer and moved to coastal fishing and reindeer herding. Following industrialization and modernization of Finland, most Finns were urbanized and employed in modern service and manufacturing occupations, with agriculture becoming a minor employer (see Economy of Finland).

Religion

Christianity spread to Finland from the Medieval times onward and original native traditions of Finnish paganism have become extinct. Finnish paganism combined various layers of Finnic, Norse, Germanic and Baltic paganism. Finnic Jumala was some sort of sky-god and is shared with Estonia. Belief of a thunder-god, Ukko or Perkele, may have Baltic origins. Elements had their own protectors, such as Ahti for waterways and Tapio for forests. Local animistic deities, "haltia", which resemble Scandinavian tomte, were also given offerings to, and bear worship was also known. Finnish neopaganism or "suomenusko" attempts to revive these traditions.

Christianity was introduced to Finns and Karelians from the east, in the form of Eastern Orthodoxy from the Medieval times onwards. However, Swedish kings conquered western parts of Finland in the late 13th century, imposing Roman Catholicism. Reformation in Sweden had the important effect that bishop Mikael Agricola, a student of Martin Luther's, introduced written Finnish, and literacy became common during the 18th century. When Finland became independent, it was overwhelmingly Lutheran Protestant. A small number of Eastern Orthodox Finns were also included, thus the Finnish government recognized both religions as "national religions". In 2017 70.9% of the population of Finland belonged to the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland, 1.1% to the Finnish Orthodox Church, 1.6% to other religious groups and 26.3% had no religious affiliation. Whereas, in Russian Ingria, there were both Lutheran and Orthodox Finns; the former were identified as Ingrian Finns while the latter were considered Izhorians or Karelians.

Subdivisions

Finns are traditionally assumed to originate from two different populations speaking different dialects of Proto-Finnic (kantasuomi). Thus, a division into Western Finnish and Eastern Finnish is made. Further, there are subgroups, traditionally called heimo,[57][58] according to dialects and local culture. Although ostensibly based on late Iron Age settlement patterns, the heimos have been constructed according to dialect during the rise of nationalism in the 19th century.

- Western[59]

- Southwest Finland and Satakunta: Finns proper (varsinaissuomalaiset)

- Tavastia: Tavastians (hämäläiset)

- Ostrobothnia: Ostrobothnians (pohjalaiset)

- Southern Ostrobothnians (eteläpohjalaiset)

- Central Ostrobothnians (keskipohjalaiset)

- Northern Ostrobothnians (pohjoispohjalaiset)

- Lapland: Lapland Finns (lappilaiset)

- Eastern

- Karelia: Finnish Karelians (karjalaiset); Karelian dialects of Finnish are distinct from the Karelian language spoken in Russia, and most of North Karelia actually speak Savonian dialects

- Savonia: Savonians (savolaiset)

- Kainuu: Kainuu Finns (kainuulaiset)

- Finnish minority groups outside Finland

- Tornedalians (länsipohjalaiset) of Norrbotten, Sweden

- Forest Finns (metsäsuomalaiset) of Sweden and Norway

- Kvens (kveenit) of Finnmark, Norway

- Ingrian Finns (inkerinsuomalaiset) of Ingria, Russia

- Finnish diaspora (ulkosuomalaiset)

- Sweden Finns (ruotsinsuomalaiset), Finnish minority in Sweden

The historical provinces of Finland can be seen to approximate some of these divisions. The regions of Finland, another remnant of a past governing system, can be seen to reflect a further manifestation of a local identity.

Journalist Ilkka Malmberg toured Finland in 1984 and looked into people's traditional and contemporary understanding of the heimos, listing them as follows: Tavastians (hämäläiset), Ostrobothnians (pohjalaiset), Lapland Finns (lappilaiset), Finns proper (varsinaissuomalaiset), Savonians (savolaiset), Kainuu Finns (kainuulaiset), and Finnish Karelians (karjalaiset).[60]

Today the importance of the tribal (heimo) identity generally depends on the region. It is strongest among the Karelians, Savonians and South Ostrobothnians.[61]

Genetics

_PC_analysis.png.webp)

The use of mitochondrial "mtDNA" (female lineage) and Y-chromosomal "Y-DNA" (male lineage) DNA-markers in tracing back the history of human populations has been gaining ground in ethnographic studies of Finnish people (e.g. the National Geographic Genographic Project[63] and the Suomi DNA-projekti.) Haplogroup U5 is estimated to be the oldest major mtDNA haplogroup in Europe and is found in the whole of Europe at a low frequency, but seems to be found in significantly higher levels among Finns, Estonians and the Sami people.[63] The older population of European hunter-gatherers that lived across large parts of Europe before the early farmers appeared are outside the genetic variation of modern populations, but most similar to Finns.[64]

With regard to the Y-chromosome, the most common haplogroups of the Finns are N1c (58%), I1a (28%), R1a (5%), and R1b (3.5%).[65] N1c, which is found mainly in a few countries in Europe (Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Russia), is a subgroup of the haplogroup N distributed across northern Eurasia and suggested to have entered Europe from Siberia.[66]

Finns are genetically closest to Karelians, a fellow Balto-Finnic group.[67][68] Finns and Karelians form a cluster with another Balto-Finnic people, the Veps.[69][68][70] They show relative affinity to Northern Russians as well,[69][71] who are known to be at least partially descended from Finno-Ugric-speakers.[68]

When not compared to these groups, Finns have been found to cluster apart from their neighboring populations, forming outlier clusters.[72] They are shifted away from the cline that most Europeans belong to[73] towards geographically distant Uralic-speakers like the Mari (while remaining genetically distant from them as well).[74] The Balto-Finnic Estonians are among the genetically closest populations of Finns, but they are drawn towards the Lithuanians and Latvians. Swedes, while being distinct from the Finns, are also closer to Finns than most European populations.[75][76][77]

Finns being an outlier population has to do with Finns having a homogenous and East Eurasian influenced gene pool.[72] Most Europeans can be modelled to have three ancestral components (hunter-gatherer, farmer and steppe), but this model does not work as such for some northeastern European populations, like the Finns and the Sami.[78] While their genome is still mostly European, they also have some additional East Asian ancestry (varies from 5 up to 10[79]–13[80] % in Finns). This component is most likely Siberian-related, best represented by the north Siberian Nganasans. The specific Siberian-like ancestry is suggested to have arrived in Northern Europe during the early Iron Age, linked to the arrival of Uralic languages.[68][78] Finns share more identity-by-descent (IBD) segments with several other Uralic-speaking peoples, including groups like Estonians, the Sami and the geographically distant Komis and Nganasans, than with their Indo-European-speaking neighbours.[68]

Finns can be roughly divided into Western and Eastern Finnish sub-clusters, which in a fine-scale analysis contain more precise clusters that are consistent with traditional dialect areas.[81] The division is related to the later settlement of Eastern Finland by a small number of Finns, who then experienced separate founder and bottleneck effects and genetic drift.[82] Variation within Finns is, according to fixation index (FST) values, exceptional in Europe. Greatest intra-Finnish FST distance is found about 60; for comparison, greatest intra-Swedish FST distance is about 25.[76][77] FST distances between Germans, French and Hungarians, for example, is only 10.[75] Thus, Finns from different parts of the country are more remote from each other genetically compared to many European peoples between themselves.[83] This is noticeable in the distances from other Europeans, as the isolation is even more profound in Eastern Finns than in Western Finns.[76] A difference can also be seen in distribution of the two major Y-DNA haplogroups of Finland: N1c, common in both Eastern Finland and Western Finland, and I1a, which is common among Western Finns but remarkably less so in Eastern Finland.[84][65] According to more detailed estimations, the frequencies of N1c and I1a are 70.9% and 19.6% in northeastern Finland, but 41.3% and 41.3% in southwestern Finland, respectively.[85] This suggests that there is also an additional Western component in the Western Finnish gene pool.[86] Despite the differences, the IBS analysis points out that Western and Eastern Finns share overall a largely similar genetic foundation.[82][87]

Theories of the origins of Finns

In the 19th century, the Finnish researcher Matthias Castrén prevailed with the theory that "the original home of Finns" was in west-central Siberia.[88]

Until the 1970s, most linguists believed that Finns arrived in Finland as late as the first century AD. However, accumulating archaeological data suggests that the area of contemporary Finland had been inhabited continuously since the end of the ice age, contrary to the earlier idea that the area had experienced long uninhabited intervals. The hunter-gatherer Sámi were pushed into the more remote northern regions.[89]

A hugely controversial theory is so-called refugia. This was proposed in the 1990s by Kalevi Wiik, a professor emeritus of phonetics at the University of Turku. According to this theory, Finno-Ugric speakers spread north as the Ice age ended. They populated central and northern Europe, while Basque speakers populated western Europe. As agriculture spread from the southeast into Europe, the Indo-European languages spread among the hunter-gatherers. In this process, both the hunter-gatherers speaking Finno-Ugric and those speaking Basque learned how to cultivate land and became Indo-Europeanized. According to Wiik, this is how the Celtic, Germanic, Slavic, and Baltic languages were formed. The linguistic ancestors of modern Finns did not switch their language due to their isolated location.[90] The main supporters of Wiik's theory are Professor Ago Künnap of the University of Tartu, Professor Kyösti Julku of the University of Oulu and Associate Professor Angela Marcantonio of the University of Rome. Wiik has not presented his theories in peer-reviewed scientific publications. Many scholars in Finno-Ugrian studies have strongly criticized the theory. Professor Raimo Anttila, Petri Kallio and brothers Ante and Aslak Aikio have rejected Wiik's theory with strong words, hinting strongly to pseudoscience, and even alt-right political biases among Wiik's supporters.[89][91] Moreover, some dismissed the entire idea of refugia, due to the existence even today of arctic and subarctic peoples. The most heated debate took place in the Finnish journal Kaltio during autumn 2002. Since then, the debate has calmed, each side retaining their positions.[92] Genotype analyses across the greater European genetic landscape have provided some credibility to the theory of the Last Glacial Maximum refugia.[93][94][95][96][97] But this does not in any way corroborate or prove that these 'refugia' spoke Uralic/Finnic, as it belies wholly independent variables that are not necessarily coeval (i.e. language spreads and genetic expansions can occur independently, at different times and in different directions).

See also

Explanatory notes

- East Karelians are generally considered to be a closely related but separate ethnic group from Finns, rather than a regional subgroup. Not only because of their Eastern Orthodox faith, but also because of their language and ethnic identity.

References

- "Population". Statistics Finland. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

Persons with Finnish background: 5,115,300

Native Finnish speakers: 4,778,490 - "Suomen ennakkoväkiluku tammikuun lopussa 5 402 758" [Finnish preliminary population by the end of January stood at 5,402,758] (in Finnish). Statistics Finland. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- "Preliminary population statistics". Statistics Finland. 23 March 2021. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- "The World Factbook – Finland". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 20 December 2022. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

Finns 93.4%, Swede 5.6%, other 1% (2006).

- "Table B04006 – People Reporting Ancestry – 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- "Foreign-born persons by country of birth and year". Statistics Sweden. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- "Fler med finsk bakgrund i Sverige" [Number of people with Finnish background in Sweden is rising]. Sveriges Radio (in Swedish). 22 February 2013. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- Statistics Canada. "Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity Highlight Tables". Archived from the original on 6 July 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- № 689–690 – Национальный состав населения России по данным переписей населения (тысяч человек) [№ 689–690 – Ethnic composition of the population of Russia according to census data (in thousands of people)] (in Russian). Demoscope Weekly. 30 June 2016. Archived from the original on 7 May 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- Australian Government – Department of Immigration and Border Protection. "Finnish Australians". Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- regionaldepartementet, Kommunal- og (8 December 2000). "St.meld. nr. 15 (2000–2001)". Regjeringa.no. Archived from the original on 21 August 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2008.

- Saressalo, L. (1996), Kveenit. Tutkimus erään pohjoisnorjalaisen vähemmistön identiteetistä. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran Toimituksia, 638. Helsinki.

- "Bevölkerung in Privathaushalten nach Migrationshintergrund im weiteren Sinn nach ausgewählten Geburtsstaaten" (in German). Statistisches Bundesamt. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- "Kahdesta miljoonasta ulkosuomalaisesta suuri osa on "kateissa" – Ulkomailla asuvat ovat aina poikkeama tilastoissa" (in Finnish). YLE. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Kahdenväliset suhteet" (in Finnish). Embassy of Finland, Madrid. Archived from the original on 26 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Paljonko suomalaisia asuu Espanjassa?" (in Finnish). Suomi-Espanja Seura. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Suomi Virossa" (in Finnish). Embassy of Finland, Tallinn. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Présentation de la Finlande". France Diplomatie – Ministère de l'Europe et des Affaires étrangères. Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- "Kahdenväliset suhteet" (in Finnish). Embassy of Finland, The Hague. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- "Kahdenväliset suhteet" (in Finnish). Embassy of Finland, Rome. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Suomi Sveitsissä" (in Finnish). Embassy of Finland, Bern. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Imigrantes internacionais registrados no Brasil". nepo.unicamp.br. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- "Kahdenväliset suhteet" (in Finnish). Embassy of Finland, Copenhagen. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Kahdenväliset suhteet" (in Finnish). Embassy of Finland, Brussels. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Kahdenväliset suhteet" (in Finnish). Embassy of Finland, Athens. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Maatiedosto Thaimaa" (in Finnish). Embassy of Finland, Bangkok. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Kahdenväliset suhteet" (in Finnish). Embassy – Embassy of Finland, Abu Dhabi. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Kahdenväliset suhteet" (in Finnish). Embassy of Finland, Beijing. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Kahdenväliset suhteet" (in Finnish). Consulate General of Finland, Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Embassy – Embassy of Finland, Dublin". Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Sefstat" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 June 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- "Suomi Itävallassa" (in Finnish). Embassy of Finland, Vienna. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Suomalaiset Puolassa" (in Finnish). Embassy of Finland, Warsaw. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Finland in Japan". Embassy of Finland, Tokyo. Archived from the original on 3 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- "Kahdenväliset suhteet" (in Finnish). Embassy of Finland, Singapore. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Suomi Israelissa" (in Finnish). Embassy of Finland, Tel Aviv. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "2013 Census ethnic group profiles". Stats.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- "Suomi Brasiliassa" (in Finnish). Embassy of Finland, Nicosia. Archived from the original on 17 April 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Population". Statistics Finland. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- "Suomalaisten esi-isät olivat maahanmuuttajia seilatessaan Suomenlahden yli – perillä odottivat muinaisgermaaniset asukkaat". Länsi-Uusimaa (in Finnish). 10 September 2020. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- "Finn noun" The Oxford Dictionary of English (revised edition). Ed. Catherine Soanes and Angus Stevenson. Oxford University Press, 2005. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Tampere University of Technology. 3 August 2007 Archived 9 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Rapo, Markus. "Tilastokeskus – Suomen väestö 2006". Tilastokeskus.fi. Archived from the original on 16 April 2008. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- "PX-Web – Valitse taulukko". pxnet2.stat.fi. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Êîìè íàðîä / Ôèííî-óãðû / Íàðîäû / Ôèííû-èíãåðìàíëàíäöû". Kominarod.ru. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- "Traditionally, immigrants were described in English and most other languages by an adjective indicating the new country of residence and a noun indicating their country of origin or their ethnic group. The term "Sweden Finns" corresponds to this naming method. Immigrants to the U.S. have, however, always been designated the "other way around" by an adjective indicating the ethnic or national origin and a noun indicating the new country of residence, for example "Finnish Americans" (never "American Finns"). The term "Finnish Swedes" corresponds to this more modern naming method that is increasingly used in most countries and languages because it emphasises the status as full and equal citizens of the new country while providing information about cultural roots. (For more information about these different naming methods see Swedish-speaking Finns.) Other possible modern terms are "Finnish ethnic minority in Sweden" and "Finnish immigrants". These may be preferable because they make a clear distinction between these two very different population groups for which use of a single term is questionable and because "Finnish Swedes" is often used like "Finland Swedes" to mean "Swedish-speaking Finns". It should perhaps also be pointed out that many Finnish and Swedish speakers are unaware that the English word "Finn" elsewhere than in this article usually means "a native or inhabitant of Finland" ("Finn". American Heritage Dictionary. 2000. Archived from the original on 27 October 2007 – via Bartleby.com.

- "Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura". Sgr.fi. Archived from the original on 8 July 2004. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- https://www.hs.fi/kuukausiliite/art-2000009054909.html Archived 26 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine (in Finnish)

- Kallio, Petri 1998: Suomi(ttavia etymologioita) – Virittäjä 4 / 1998.

- "Archived copy". vesta.narc.fi. Archived from the original on 6 October 2007. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

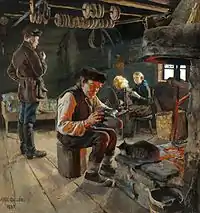

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "vanhempi mies "muinaissuomalaisessa kansanpuvussa" Mikkelin Tuukkalan löytöjen mukaan". Finna (Catalogue record). Archived from the original on 1 January 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- Lang, Valter (2020). Homo Fennicus – Itämerensuomalaisten etnohistoria. Finnish Literature Society. pp. 253–255. ISBN 978-951-858-130-0.

- Lang, Valter (2020). Homo Fennicus – Itämerensuomalaisten etnohistoria. Finnish Literature Society. p. 269. ISBN 978-951-858-130-0.

- Lang, Valter (2020). Homo Fennicus – Itämerensuomalaisten etnohistoria. Finnish Literature Society. p. 275. ISBN 978-951-858-130-0.

- Lang, Valter (2020). Homo Fennicus – Itämerensuomalaisten etnohistoria. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. p. 275. ISBN 978-951-858-130-0.

- Lang, Valter (2020). Homo Fennicus – Itämerensuomalaisten etnohistoria. Finnish Literature Society. pp. 316–317. ISBN 978-951-858-130-0.

- Helminen, MInna. "Legenda piispa Henrikistä ja Lallista". opinnot.internetix.fi. Otavan Opisto. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- Heimo is often mistranslated as "tribe", but a heimo is a dialectal and cultural kinship rather than a genetic kinship, and represents a much larger and disassociated group of people. Suomalaiset heimot Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. From the book Hänninen, K. Kansakoulun maantieto ja kotiseutuoppi yksiopettajaisia kouluja varten. Osakeyhtiö Valistus, Raittiuskansan Kirjapaino Oy, Helsinki 1929, neljäs painos. The excerpt from a 1929 school book shows the generalized concept. Retrieved 13 January 2008. (in Finnish)

- Sedergren, J (2002) Evakko – elokuva ja romaani karjalaispakolaisista"Ennen & nyt 3/02, Jari Sedergren: Evakko - elokuva ja romaani pakolaisuudesta". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Ennen & nyt 3/2002. Retrieved 13 January 2008. (in Finnish) The reference is a movie review, which however discusses the cultural phenomenon of the evacuation of Finnish Karelia using and analyzing the heimo concept rather generally. - Topelius, Z. (1876) Maamme kirja. Lukukirja alimmaisille oppilaitoksille Suomessa. Toinen jakso. Suom. Johannes Bäckvall. Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (in Finnish) Retrieved 13 January 2008. (in Finnish) Pp. 187 onwards shows the stereotypical generalizations of the heimos listed here.

- Malmberg, Ilkka; Vanhatalo, Tapio (1985). Heimoerot esiin ja härnäämään!. Weilin+Göös. pp. 5–6. ISBN 951-35-3386-7.

- "Studies on Finnish attitudes and identities | The Finnish Cultural Foundation". skr.fi. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Nelis, Mari; Esko, Tõnu; Mägi, Reedik; Zimprich, Fritz; Zimprich, Alexander; Toncheva, Draga; Karachanak, Sena; Piskáčková, Tereza; Balaščák, Ivan; Peltonen, Leena; Jakkula, Eveliina (8 May 2009). "Genetic Structure of Europeans: A View from the North–East". PLOS ONE. 4 (5): e5472. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.5472N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005472. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2675054. PMID 19424496.

- "Atlas of the Human Journey – The Genographic Project". 5 April 2008. Archived from the original on 5 April 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Science: Stone Age Skeletons Suggest Europe's First Farmers Came From Southern Europe". AAAS – The World's Largest General Scientific Society. 26 April 2012. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- Lappalainen, T; Koivumäki, S; Salmela, E; Huoponen, K; Sistonen, P; Savontaus, M. L.; Lahermo, P (2006). "Regional differences among the Finns: A Y-chromosomal perspective". Gene. 376 (2): 207–15. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2006.03.004. PMID 16644145.

- Rootsi, Siiri; Zhivotovsky, Lev A; Baldovič, Marian; Kayser, Manfred; Kutuev, Ildus A; Khusainova, Rita; Bermisheva, Marina A; Gubina, Marina; Fedorova, Sardana A; Ilumäe, Anne-Mai; Khusnutdinova, Elza K; Voevoda, Mikhail I; Osipova, Ludmila P; Stoneking, Mark; Lin, Alice A; Ferak, Vladimir; Parik, Jüri; Kivisild, Toomas; Underhill, Peter A; Villems, Richard (2007). "A counter-clockwise northern route of the Y-chromosome haplogroup N from Southeast Asia towards Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 15 (2): 204–211. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201748. ISSN 1018-4813. PMID 17149388.

- Lang, Valter (2020). Homo Fennicus – Itämerensuomalaisten etnohistoria. Finnish Literature Society. p. 95. ISBN 9789518581300.

- Tambets, Kristiina; Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Hudjashov, Georgi; Ilumäe, Anne-Mai; Rootsi, Siiri; Honkola, Terhi; Vesakoski, Outi; Atkinson, Quentin; Skoglund, Pontus; Kushniarevich, Alena; Litvinov, Sergey (21 September 2018). "Genes reveal traces of common recent demographic history for most of the Uralic-speaking populations". Genome Biology. 19 (1): 139. doi:10.1186/s13059-018-1522-1. ISSN 1474-7596. PMC 6151024. PMID 30241495.

- Zhernakova, Daria V.; Brukhin, Vladimir; Malov, Sergey; Oleksyk, Taras K.; Koepfli, Klaus Peter; Zhuk, Anna; Dobrynin, Pavel; Kliver, Sergei; Cherkasov, Nikolay; Tamazian, Gaik; Rotkevich, Mikhail; Krasheninnikova, Ksenia; Evsyukov, Igor; Sidorov, Sviatoslav; Gorbunova, Anna (January 2020). "Genome-wide sequence analyses of ethnic populations across Russia". Genomics. 112 (1): 442–458. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2019.03.007. ISSN 1089-8646. PMID 30902755. S2CID 85455300.

- Pankratov, Vasili; Montinaro, Francesco; Kushniarevich, Alena; Hudjashov, Georgi; Jay, Flora; Saag, Lauri; Flores, Rodrigo; Marnetto, Davide; Seppel, Marten; Kals, Mart; Võsa, Urmo; Taccioli, Cristian; Möls, Märt; Milani, Lili; Aasa, Anto (25 July 2020). "Differences in local population history at the finest level: the case of the Estonian population". European Journal of Human Genetics. 28 (11): 1580–1591. doi:10.1038/s41431-020-0699-4. ISSN 1476-5438. PMC 7575549. PMID 32712624.

- Kushniarevich, Alena; Utevska, Olga; Chuhryaeva, Marina; Agdzhoyan, Anastasia; Dibirova, Khadizhat; Uktveryte, Ingrida; Möls, Märt; Mulahasanovic, Lejla; Pshenichnov, Andrey; Frolova, Svetlana; Shanko, Andrey; Metspalu, Ene; Reidla, Maere; Tambets, Kristiina; Tamm, Erika (2 September 2015). "Genetic Heritage of the Balto-Slavic Speaking Populations: A Synthesis of Autosomal, Mitochondrial and Y-Chromosomal Data". PLOS ONE. 10 (9): e0135820. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1035820K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135820. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4558026. PMID 26332464.

- Översti, Sanni; Majander, Kerttu; Salmela, Elina; Salo, Kati; Arppe, Laura; Belskiy, Stanislav; Etu-Sihvola, Heli; Laakso, Ville; Mikkola, Esa; Pfrengle, Saskia; Putkonen, Mikko; Taavitsainen, Jussi-Pekka; Vuoristo, Katja; Wessman, Anna; Sajantila, Antti; Oinonen, Markku; Haak, Wolfgang; Schuenemann, Verena J.; Krause, Johannes; Palo, Jukka U.; Onkamo, Päivi (15 November 2019). "Översti, S., Majander, K., Salmela, E. et al. Human mitochondrial DNA lineages in Iron-Age Fennoscandia suggest incipient admixture and eastern introduction of farming-related maternal ancestry. Sci Rep 9, 16883 (2019)". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 16883. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-51045-8. PMC 6858343. PMID 31729399.

Finns are also genetically distinct from their neighboring populations and form outliers in the genetic variation within Europe. This genetic uniqueness derives from both reduced genetic diversity and an Asian influence to the gene pool.

- Lao, Oscar; Lu, Timothy T.; Nothnagel, Michael; Junge, Olaf; Freitag-Wolf, Sandra; Caliebe, Amke; Balascakova, Miroslava; Bertranpetit, Jaume; Bindoff, Laurence A.; Comas, David; Holmlund, Gunilla; Kouvatsi, Anastasia; Macek, Milan; Mollet, Isabelle; Parson, Walther (2008). "Correlation between Genetic and Geographic Structure in Europe". Current Biology. 18 (16): 1241–1248. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.049. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 18691889. S2CID 16945780.

- Santos, Patrícia; Gonzàlez-Fortes, Gloria; Trucchi, Emiliano; Ceolin, Andrea; Cordoni, Guido; Guardiano, Cristina; Longobardi, Giuseppe; Barbujani, Guido (2020). "More Rule than Exception: Parallel Evidence of Ancient Migrations in Grammars and Genomes of Finno-Ugric Speakers". Genes. 11 (12): 1491. doi:10.3390/genes11121491. ISSN 2073-4425. PMC 7763979. PMID 33322364.

- Nelis; et al. (2009). "Genetic Structure of Europeans: A View from the North-East". PLOS ONE. 4 (5): e5472. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.5472N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005472. PMC 2675054. PMID 19424496.

- Salmela; et al. (2011). "Swedish Population Substructure Revealed by Genome-Wide Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Data". PLOS ONE. 6 (2): e16747. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...616747S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016747. PMC 3036708. PMID 21347369.

- Jakkula; et al. (2008). "The Genome-wide Patterns of Variation Expose Significant Substructure in a Founder Population". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 83 (6): 787–794. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.11.005. PMC 2668058. PMID 19061986.

- Lamnidis, Thiseas C.; Majander, Kerttu; Jeong, Choongwon; Salmela, Elina; Wessman, Anna; Moiseyev, Vyacheslav; Khartanovich, Valery; Balanovsky, Oleg; Ongyerth, Matthias; Weihmann, Antje; Sajantila, Antti (27 November 2018). "Ancient Fennoscandian genomes reveal origin and spread of Siberian ancestry in Europe". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 5018. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.5018L. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07483-5. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6258758. PMID 30479341.

This model, however, does not fit well for present-day populations from north-eastern Europe such as Saami, Russians, Mordovians, Chuvash, Estonians, Hungarians, and Finns: they carry additional ancestry seen as increased allele sharing with modern East Asian populations1,3,9,10. Additionally, within the Bolshoy population, we observe the derived allele of rs3827760 in the EDAR gene, which is found in near-fixation in East Asian and Native American populations today, but is extremely rare elsewhere37, and has been linked to phenotypes related to tooth shape38 and hair morphology39 (Supplementary Data 2). To further test differential relatedness with Nganasan in European populations and in the ancient individuals in this study, we calculated f4(Mbuti, Nganasan; Lithuanian, Test) (Fig. 3). Consistent with f3-statistics above, all the ancient individuals and modern Finns, Saami, Mordovians and Russians show excess allele sharing with Nganasan when used as Test populations.

- "Keitä me olemme?". HS.fi (in Finnish). 2018. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- Qin, Pengfei; Zhou, Ying; Lou, Haiyi; Lu, Dongsheng; Yang, Xiong; Wang, Yuchen; Jin, Li; Chung, Yeun-Jun; Xu, Shuhua (2 April 2015). "Quantitating and Dating Recent Gene Flow between European and East Asian Populations". Scientific Reports. 5 (1): 9500. Bibcode:2015NatSR...5E9500Q. doi:10.1038/srep09500. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4382708. PMID 25833680.

- "Itä- ja länsisuomalaiset erottaa jo geeneistä – raja noudattaa Pähkinäsaaren rauhan rajaa". paivanlehti.fi (in Finnish). 2017. Archived from the original on 1 August 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- Salmela, Elina; Lappalainen, Tuuli; Fransson, Ingegerd; Andersen, Peter M.; Dahlman-Wright, Karin; Fiebig, Andreas; Sistonen, Pertti; Savontaus, Marja-Liisa; Schreiber, Stefan; Kere, Juha; Lahermo, Päivi (24 October 2008). "Genome-Wide Analysis of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms Uncovers Population Structure in Northern Europe". PLOS ONE. 3 (10): e3519. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3519S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003519. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2567036. PMID 18949038.

- Häkkinen, Jaakko (2011). "Seven Finnish populations: the greatest intranational substructure in Europe". Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- Lang, Valter (2020). Homo Fennicus – Itämerensuomalaisten etnohistoria. Finnish Literature Society. ISBN 9789518581300.

- Assessing Finnish Y-chromosomal haplogroups using genotyping array data – Towards understanding the role of Y in complex disease – Annina Preussner 2021 University of Helsinki

- Lang, Valter (2020). Homo Fennicus – Itämerensuomalaisten etnohistoria. Finnish Literature Society. p. 94. ISBN 9789518581300.

- "Lehti: Geneettinen analyysi kertoo maakuntasi". www.iltalehti.fi (in Finnish). 2008. Archived from the original on 22 July 2023. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- (in Finnish) Lehikoinen, L. (1986) D.E.D Europaeus kirjasuomen kehittäjänä ja tutkijana Archived 27 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Virittäjä, 1986, 178–202. with German abstract. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- Aikio, A & Aikio, A. (2001). Heimovaelluksista jatkuvuuteen – suomalaisen väestöhistorian tutkimuksen pirstoutuminen. Muinaistutkija 4/2001. (in Finnish) Retrieved 1-7-2008 Archived 27 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Kaltio – Pohjoinen kulttuurilehti – Uusin kaltio". Kaltio.fi. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- "Kaltio – Pohjoinen kulttuurilehti – Uusin kaltio". Kaltio.fi. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- The debate (in Finnish) is accessible in Kaltio's website Archived 8 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- Semino O, Passarino G, Oefner PJ, Lin AA, Arbuzova S, Beckman LE, De Benedictis G, Francalacci P, Kouvatsi A, Limborska S, Marcikiae M, Mika A, Mika B, Primorac D, Santachiara-Benerecetti AS, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Underhill PA (10 November 2000). "The genetic legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in extant Europeans: a Y chromosome perspective". Science. 290 (5494): 1155–9. Bibcode:2000Sci...290.1155S. doi:10.1126/science.290.5494.1155. PMID 11073453.

- Malaspina P, Cruciani F, Santolamazza P, Torroni A, Pangrazio A, Akar N, Bakalli V, Brdicka R, Jaruzelska J, Kozlov A, Malyarchuk B, Mehdi SQ, Michalodimitrakis E, Varesi L, Memmi MM, Vona G, Villems R, Parik J, Romano V, Stefan M, Stenico M, Terrenato L, Novelletto A, Scozzari R (September 2000). "Patterns of male-specific inter-population divergence in Europe, West Asia and North Africa" (PDF). Ann Hum Genet. 64(Pt 5) (Pt 5): 395–412. doi:10.1046/j.1469-1809.2000.6450395.x. PMID 11281278. S2CID 10824631. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- Torroni, Antonio; Hans-Jürgen Bandelt; Vincent Macaulay; Martin Richards; Fulvio Cruciani; Chiara Rengo; Vicente Martinez-Cabrera; et al. (2001). "A signal, from human mtDNA, of postglacial recolonization in Europe". American Journal of Human Genetics. 69 (4): 844–52. doi:10.1086/323485. PMC 1226069. PMID 11517423.

- Achilli, Alessandro; Chiara Rengo; Chiara Magri; Vincenza Battaglia; Anna Olivieri; Rosaria Scozzari; Fulvio Cruciani; et al. (2004). "The molecular dissection of mtDNA haplogroup H confirms that the Franco-Cantabrian glacial refuge was a major source for the European gene pool". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 75 (5): 910–918. doi:10.1086/425590. PMC 1182122. PMID 15382008.

- Pala, Maria; Anna Olivieri; Alessandro Achilli; Matteo Accetturo; Ene Metspalu; Maere Reidla; Erika Tamm; et al. (2012). "Mitochondrial DNA Signals of Late Glacial Recolonization of Europe from Near Eastern Refugia". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 90 (5): 915–924. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.003. PMC 3376494. PMID 22560092.