History of Finland

The history of Finland begins around 9,000 BC during the end of the last glacial period. Stone Age cultures were Kunda, Comb Ceramic, Corded Ware, Kiukainen, and Pöljä cultures. The Finnish Bronze Age started in approximately 1,500 BC and the Iron Age started in 500 BC and lasted until 1,300 AD. Finnish Iron Age cultures can be separated into Finnish proper, Tavastian and Karelian cultures.[1] The earliest written sources mentioning Finland start to appear from the 12th century onwards when the Catholic Church started to gain a foothold in Southwest Finland.[2]

| Part of a series on |

| Scandinavia |

|---|

|

Due to the Northern Crusades and Swedish colonisation of some Finnish coastal areas, most of the region became a part of the Kingdom of Sweden and the realm of the Catholic Church from the 13th century onwards. After the Finnish War in 1809, Finland was ceded to the Russian Empire, making this area the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland. The Lutheran religion dominated. Finnish nationalism emerged in the 19th century. It focused on Finnish cultural traditions, folklore, and mythology, including music and—especially—the highly distinctive language and lyrics associated with it. One product of this era was the Kalevala, one of the most significant works of Finnish literature. The catastrophic Finnish famine of 1866–1868 was followed by eased economic regulations and extensive emigration.

In 1917, Finland declared independence. A civil war between the Finnish Red Guards and the White Guard ensued a few months later, with the Whites gaining the upper hand during the springtime of 1918. After the internal affairs stabilized, the still mainly agrarian economy grew relatively quickly. Relations with the West, especially Sweden and Britain, were strong but tensions remained with the Soviet Union. During World War II, Finland fought twice against the Soviet Union, first defending its independence in the Winter War and then invading the Soviet Union in the Continuation War. In the peace settlement Finland ended up ceding a large part of Karelia and some other areas to the Soviet Union. However, Finland remained an independent democracy in Northern Europe.

In the latter half of its independent history, Finland has maintained a mixed economy. Since its post–World War II economic boom in the 1970s, Finland's GDP per capita has been among the world's highest. The expanded welfare state of Finland from 1970 and 1990 increased the public sector employees and spending and the tax burden imposed on the citizens. In 1992, Finland simultaneously faced economic overheating and depressed Western, Russian, and local markets. Finland joined the European Union in 1995, and replaced the Finnish markka with the euro in 2002. According to a 2016 poll, 61% of Finns preferred not to join NATO.[3] Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the numbers had shifted significantly, with 62% in favour of Finland joining NATO and 16% against.[4] Finland started to pursue membership in the alliance and eventually joined NATO on 4 April 2023.

Stone Age

Paleolithic

If confirmed, the oldest archeological site in Finland would be the Wolf Cave in Kristinestad, in Ostrobothnia. The site would be the only pre-glacial (Neanderthal) site so far discovered in the Nordic countries, and it is approximately 125,000 years old.[6]

Mesolithic

The last ice age in the area of the modern-day Finland ended c. 9000 BC. Starting about that time, people migrated to the area of Finland from the south and southeast. Their culture represented a mixture of Kunda, Butovo, and Veretje cultures. At the same time, northern Finland was inhabited via the coast of Norway.[7] The oldest confirmed evidence of post-glacial human settlements in Finland is from the area of Ristola in Lahti and from Orimattila, from c. 8900 BC. Finland has been continuously inhabited at least since the end of the last ice age up to the present.[8] The earliest post-glacial inhabitants of the present-day area of Finland were probably mainly seasonal hunter-gatherers. Among finds is the net of Antrea, the oldest fishing net known ever to have been excavated (calibrated carbon dating: ca. 8300 BC).

Neolithic

By 5300 BC, pottery was present in Finland. The earliest samples belong to the Comb Ceramic cultures, known for their distinctive decorating patterns. This marks the beginning of the neolithic period for Finland, although subsistence was still based on hunting and fishing. Extensive networks of exchange existed across Finland and northeastern Europe during the 5th millennium BC. For example, flint from Scandinavia and the Valdai Hills, amber from Scandinavia and the Baltic region, and slate from Scandinavia and Lake Onega found their way into Finnish archaeological sites, while asbestos and soap stone from Finland (e.g. the area of Saimaa) were found in other regions. Rock paintings—apparently related to shamanistic and totemistic belief systems—have been found, especially in Eastern Finland, e.g. Astuvansalmi.

Between 3500 and 2000 BC, monumental stone enclosures, colloquially known as Giant's Churches (Finnish: Jätinkirkko), were constructed in the Ostrobothnia region.[9] The purpose of the enclosures is unknown.[9]

In recent years, a dig at the Kierikki site north of Oulu on the River Ii has changed the image of Finnish neolithic Stone Age culture. The site had been inhabited year-round and its inhabitants traded extensively. Kierikki culture is also seen as a subtype of Comb Ceramic culture. More of the site is excavated annually.[10]

From 3200 BC onwards, either immigrants or a strong cultural influence from south of the Gulf of Finland settled in southwestern Finland. This culture was a part of the European Battle Axe cultures, which have often been associated with the movement of the Indo-European speakers. The Battle Axe, or Cord Ceramic, culture seems to have practiced agriculture and animal husbandry outside of Finland, but the earliest confirmed traces of agriculture in Finland date later, approximately to the 2nd millennium BC. Further inland, societies retained their hunting-gathering lifestyles for the time being.[11]

The Battle Axe and Comb Ceramic cultures eventually merged, giving rise to the Kiukainen culture that existed between 2300 BC and 1500 BC, and was fundamentally a comb ceramic tradition with cord ceramic characteristics.

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age began some time after 1500 BC. The coastal regions of Finland were a part of the Nordic Bronze Culture, whereas in the inland regions the influences came from the bronze-using cultures of northern and eastern Russia.[12]

Iron Age

The Iron Age in Finland is considered to have lasted from c. 500 BC until c. 1300 AD.[13] Written records of Finland become more common due to the Northern Crusades led by the Catholic Church in the 12th and 13th centuries. As the Finnish Iron Age lasted almost two millennia, it is further divided into six sub-periods:[13]

- Pre-Roman period: 500 BC – 1 BC

- Roman period: 1 AD – 400 AD

- Migration period: 400 AD – 575 AD

- Merovingian period: 575 AD – 800 AD

- Viking age period: 800 AD – 1025 AD

- Crusade period: 1033 AD – 1300 AD

Very few written records of Finland or its people remain in any language of the era. Written sources are of foreign origin and include Tacitus's description of Fenni in his work Germania, runestones, the sagas written down by Snorri Sturluson, as well as the 12th- and 13th-century ecclesiastical letters by the Pope. Numerous other sources from the Roman period onwards contain brief mentions of ancient Finnish kings and place names, as such defining Finland as a kingdom and noting the culture of its people.

The oldest surviving mention of the word Suomi (Finland in Finnish) is in the annals of the Frankish Empire written between 741 and 829. At 811, annals mention a person named Suomi in connection with a peace agreement.[14][15] The name Suomi as the name of Finland is nowadays used in Finnic languages, Sámi, Latvian, Lithuanian and Scottish Gaelic.

Currently the oldest known Scandinavian documents mentioning Finland are two runestones: Söderby, Sweden, with the inscription finlont (U 582), and Gotland with the inscription finlandi (G 319) dating from the 11th century.[16] However, as the long continuum of the Finnish Iron Age into the historical Medieval period of Europe suggests, the primary source of information of the era in Finland is based on archaeological findings[13] and modern applications of natural scientific methods like those of DNA analysis[17] or computer linguistics.

Production of iron during the Finnish Iron Age was adopted from the neighboring cultures in the east, west and south about the same time as the first imported iron artifacts appear.[13] This happened almost simultaneously in various parts of the country.

Pre-Roman period: 500 BC – 1 BC

The Pre-Roman period of the Finnish Iron Age is scarcest in findings, but the known ones suggest that cultural connections to other Baltic cultures were already established.[13] The archeological findings of Pernå and Savukoski provides proof of this argument. Many of the era's dwelling sites are the same as those of the Neolithic. Most of the iron of the era was produced on site.[13]

Roman period: 1 AD – 400 AD

The Roman period brought along an influx of imported iron (and other) artifacts like Roman wine glasses and dippers as well as various coins of the Empire. During this period the (proto) Finnish culture stabilized on the coastal regions and larger graveyards become commonplace. The prosperity of the Finns rose to the level that the vast majority of gold treasures found within Finland date back to this period.[13]

Migration period: 400 AD – 575 AD

The Migration period saw the expansion of land cultivation inland, especially in Southern Bothnia, and the growing influence of Germanic cultures, both in artifacts like swords and other weapons and in burial customs. However most iron as well as its forging was of domestic origin, probably from bog iron.[13]

Merovingian period: 575 AD – 800 AD

The Merovingian period in Finland gave rise to a distinctive fine crafts culture of its own, visible in the original decorations of domestically produced weapons and jewelry. The finest luxury weapons, however, were imported from Western Europe. The very first Christian burials are from the latter part of this era as well. In the Leväluhta burial findings, the average height of a man was originally thought to be just 158 cm and that of a woman 147 cm,[13] but recent research has corrected these numbers upwards and has confirmed that the people buried in Leväluhta were of average height for that era in Europe.

Recent findings suggest that Finnish trade connections became more active during the 8th century, bringing an influx of silver onto Finnish markets.[13] The opening of the eastern route to Constantinople via Finland's southern coastline archipelago brought Arabic and Byzantine artifacts into the excavation findings of the era.

The earliest findings of imported iron blades and local iron working appear in 500 BC. From about 50 AD, there are indications of a more intense long-distance exchange of goods in coastal Finland. Inhabitants exchanged their products, presumably mostly furs, for weapons and ornaments with the Balts and the Scandinavians, as well as with the peoples along the traditional eastern trade routes. The existence of richly furnished burials, usually with weapons, suggests that there was a chiefly elite in the southern and western parts of the country. Hillforts spread over most of southern Finland at the end of the Iron and early Medieval Ages. There is no commonly accepted evidence of early state formations in Finland, and the presumably Iron Age origins of urbanization are contested.

Chronology of languages in Finland

The question of the timelines for the evolution and the spreading of the current Finnic languages is controversial, and new theories challenging older ones have been introduced continuously.

It was for a long time widely believed[18][19][20] that Finno-Ugric (the western branch of the Uralic) languages were first spoken in Finland and the adjacent areas during the Comb Ceramic period, around 4000 BC at the latest. During the 2nd millennium BC these evolved—possibly under an Indo-European (most likely Baltic) influence—into proto-Sami (inland) and Proto-Finnic (coastland). In contrast, A. Aikio and J. Häkkinen propose that the Finno-Ugric languages arrived in the Gulf of Finland area during the Late Bronze Age. Valter Lang has proposed that the Finnic and Saami languages arrived there in the early Bronze Age, possibly connected to the Seima-Turbino phenomenon.[21][22][23] This would also imply that Finno-Ugric languages in Finland were preceded by a Northwestern Indo-European language, at least to the extent the latter can be associated with the Cord Ceramic culture, as well as by hitherto unknown Paleo-European languages.[23] The center of expansion for the Proto-Finnic language is posited to have been located on the southern coast of the Gulf of Finland.[23][24] The Finnish language is thought to have started to differentiate during the Iron Age starting from the earliest centuries of the Common Era.

Cultural influences from a variety of places are visible in the Finnish archaeological finds from the very first settlements onwards. For example, archaeological finds from Finnish Lapland suggest the presence of the Komsa culture from Norway. The Sujala finds, which are equal in age with the earliest Komsa artifacts, may also suggest a connection to the Swiderian culture.[25] Southwestern Finland belonged to the Nordic Bronze Age, which may be associated with Indo-European languages, and according to Finnish Germanist Jorma Koivulehto speakers of Proto-Germanic language in particular. Artifacts found in Kalanti and the province of Satakunta, which have long been monolingually Finnish, and their place names have made several scholars argue for an existence of a proto-Germanic speaking population component a little later, during the Early and Middle Iron Age.[26][27]

The Swedish colonisation of the Åland Islands, Turku archipelago and Uusimaa could possibly have started in the 12th century but reached its height in the 13th and 14th centuries, when it also affected the Eastern Uusimaa and Pohjanmaa regions.[28][29] The oldest Swedish place names in Finland are from this period[30] as well as the Swedish-speaking population of Finland.[29]

Finland under Swedish rule

Middle Ages

Contact between Sweden and what is now Finland was considerable even during pre-Christian times; the Vikings were known to the Finns due to their participation in both commerce and plundering. There is possible evidence of Viking settlement in the Finnish mainland.[31] The Åland Islands probably had Swedish settlement during the Viking Period. However, some scholars claim that the archipelago was deserted during the 11th century. According to the archaeological finds, Christianity gained a foothold in Finland during the 11th century. According to the very few written documents that have survived, the church in Finland was still in its early development in the 12th century. Later medieval legends from late 13th century describe Swedish attempts to conquer and Christianize Finland sometime in the mid-1150s.

In the early 13th century, Bishop Thomas became the first known bishop of Finland. There were several secular powers who aimed to bring the Finnish tribes under their rule. These were Sweden, Denmark, the Republic of Novgorod in northwestern Russia, and probably the German crusading orders as well. Finns had their own chiefs, but most probably no central authority. At the time there can be seen three cultural areas or tribes in Finland: Finns, Tavastians and Karelians.[32] Russian chronicles indicate there were several conflicts between Novgorod and the Finnic tribes from the 11th or 12th century to the early 13th century.

It was the Swedish regent, Birger Jarl, who allegedly established Swedish rule in Finland through the Second Swedish Crusade, most often dated to 1249. The Eric Chronicle, the only source narrating the crusade, describes that it was aimed at Tavastians. A papal letter from 1237 states that the Tavastians had reverted from Christianity to their old ethnic faith.

Novgorod gained control in Karelia in 1278, the region inhabited by speakers of Eastern Finnish dialects. Sweden however gained the control of Western Karelia with the Third Swedish Crusade in 1293. Western Karelians were from then on viewed as part of the western cultural sphere, while eastern Karelians turned culturally to Russia and Orthodoxy. While eastern Karelians remain linguistically and ethnically closely related to the Finns, they are generally considered a separate people.[33] Thus, the northern part of the border between Catholic and Orthodox Christendom came to lie at the eastern border of what would become Finland with the Treaty of Nöteborg with Novgorod in 1323.

During the 13th century, Finland was integrated into medieval European civilization. The Dominican order arrived in Finland around 1249 and came to exercise great influence there. In the early 14th century, the first records of Finnish students at the Sorbonne appear. In the southwestern part of the country, an urban settlement evolved in Turku. Turku was one of the biggest towns in the Kingdom of Sweden, and its population included German merchants and craftsmen. Otherwise the degree of urbanization was very low in medieval Finland. Southern Finland and the long coastal zone of the Gulf of Bothnia had sparse farming settlements, organized as parishes and castellanies. In the other parts of the country a small population of Sami hunters, fishermen, and small-scale farmers lived. These were exploited by the Finnish and Karelian tax collectors. During the 12th and 13th centuries, great numbers of Swedish settlers moved to the southern and northwestern coasts of Finland, to the Åland Islands, and to the archipelago between Turku and the Åland Islands. In these regions, the Swedish language is widely spoken even today. Swedish came to be the language of the upper class in many other parts of Finland as well.

The name Finland originally signified only the southwestern province, which has been known as Finland Proper since the 18th century. The first known mention of Finland is in runestone Gs 13 from the 11th century. The original Swedish term for the realm's eastern part was Österlands ('Eastern Lands'), a plural, meaning the area of Finland Proper, Tavastia, and Karelia. This was later replaced by the singular form Österland, which was in use between 1350 and 1470.[34] In the 15th century Finland began to be used synonymously with Österland. The concept of a Finnish country in the modern sense developed slowly from the 15th to 18th centuries.

During the 13th century, the bishopric of Turku was established. Turku Cathedral was the center of the cult of Saint Henry of Uppsala, and naturally the cultural center of the bishopric. The bishop had ecclesiastical authority over much of today's Finland, and was usually the most powerful man there. Bishops were often Finns, whereas the commanders of castles were more often Scandinavian or German noblemen. In 1362, representatives from Finland were called to participate in the elections for the king of Sweden. As such, that year is often considered when Finland was incorporated into the Kingdom of Sweden. As in the Scandinavian part of the kingdom, the gentry or (lower) nobility consisted of magnates and yeomen who could afford armament for a man and a horse; these were concentrated in the southern part of Finland.

The strong fortress of Viborg (Finnish: Viipuri, Russian: Vyborg) guarded the eastern border of Finland. Sweden and Novgorod signed the Treaty of Nöteborg (Pähkinäsaari in Finnish) in 1323, but that did not last long. In 1348 the Swedish king Magnus Eriksson staged a failed crusade against Orthodox "heretics", managing only to alienate his supporters and ultimately lose his crown. The bones of contention between Sweden and Novgorod were the northern coastline of the Gulf of Bothnia and the wilderness regions of Savo in Eastern Finland. Novgorod considered these as hunting and fishing grounds of its Karelian subjects, and protested against the slow infiltration of Catholic settlers from the West. Occasional raids and clashes between Swedes and Novgorodians occurred during the late 14th and 15th centuries, but for most of the time an uneasy peace prevailed.

During the 1380s, a civil war in the Scandinavian part of Sweden brought unrest to Finland as well. The victor of this struggle was Queen Margaret I of Denmark, who brought the three Scandinavian kingdoms of Sweden, Denmark and, Norway under her rule (the Kalmar Union) in 1389. One of the phenomena that appeared in those days with the unrest, was the notorious pirates, known as the Victual Brothers, who operated in the Baltic Sea in the Middle Ages to terrorize the coastal areas of Finland, and among other things, Korsholm Castle in Ostrobothnia, Turku Castle in the Finland Proper and also the Turku's Archipelago Sea were the most significant domains for the pirates.[35] The next 130 years or so were characterized by attempts of different Swedish factions to break out of the Union. Finland was sometimes involved in these struggles, but in general the 15th century seems to have been a relatively prosperous time, characterized by population growth and economic development. Towards the end of the 15th century, however, the situation on the eastern border became more tense. The Principality of Moscow conquered Novgorod, preparing the way for a unified Russia, and from 1495 to 1497 a war was fought between Sweden and Russia. The fortress-town of Viborg withstood a Russian siege; according to a contemporary legend, it was saved by a miracle.

16th century

_en2.png.webp)

In 1521 the Kalmar Union collapsed and Gustav Vasa became the King of Sweden. During his rule, the Swedish church was reformed. The state administration underwent extensive reforms and development too, giving it a much stronger grip on the life of local communities—and ability to collect higher taxes. Following the policies of the Reformation, in 1551 Mikael Agricola, bishop of Turku, published his translation of the New Testament into the Finnish language.

In 1550 Helsinki was founded by Gustav Vasa under the name of Helsingfors, but remained little more than a fishing village for more than two centuries.

King Gustav Vasa died in 1560 and his crown was passed to his three sons in separate turns. King Erik XIV started an era of expansion when the Swedish crown took the city of Tallinn in Estonia under its protection in 1561. This action contributed to the early stages of the Livonian War which was a warlike era which lasted for 160 years. In the first phase, Sweden fought for the lordship of Estonia and Latvia against Denmark, Poland and Russia. The common people of Finland suffered because of drafts, high taxes, and abuse by military personnel. This resulted in the Cudgel War of 1596–1597, a desperate peasant rebellion, which was suppressed brutally and bloodily. A peace treaty (the Treaty of Teusina) with Russia in 1595 moved the border of Finland further to the east and north, very roughly where the modern border lies.

An important part of the 16th-century history of Finland was growth of the area settled by the farming population. The crown encouraged farmers from the province of Savonia to settle the vast wilderness regions in Middle Finland. This often forced the original Sami population to leave. Some of the wilderness settled was traditional hunting and fishing territory of Karelian hunters. During the 1580s, this resulted in a bloody guerrilla warfare between the Finnish settlers and Karelians in some regions, especially in Ostrobothnia.

17th century

In 1611–1632 Sweden was ruled by King Gustavus Adolphus, whose military reforms transformed the Swedish army from a peasant militia into an efficient fighting machine, possibly the best in Europe. The conquest of Livonia was now completed, and some territories were taken from internally divided Russia in the Treaty of Stolbovo. In 1630, the Swedish (and Finnish) armies marched into Central Europe, as Sweden had decided to take part in the great struggle between Protestant and Catholic forces in Germany, known as the Thirty Years' War. The Finnish light cavalry was known as the Hakkapeliitat.[36][37]

After the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, the Swedish Empire was one of the most powerful countries in Europe. During the war, several important reforms had been made in Finland:

- 1637–1640 and 1648–1654: Count Per Brahe functioned as general governor of Finland. Many important reforms were made and many towns were founded. His period of administration is generally considered very beneficial to the development of Finland.

- 1640: Finland's first university, the Academy of Åbo, was founded in Turku at the proposal of Count Per Brahe by Queen Christina of Sweden.

- 1642: the whole Bible was published in Finnish.

However, the high taxation, continuing wars and the cold climate (the Little Ice Age) made the Imperial era of Sweden rather gloomy times for Finnish peasants. In 1655–1660, the Northern Wars were fought, taking Finnish soldiers to the battle-fields of Livonia, Poland and Denmark. In 1676, the political system of Sweden was transformed into an absolute monarchy.

In Middle and Eastern Finland, great amounts of tar were produced for export. European nations needed this material for the maintenance of their fleets. According to some theories, the spirit of early capitalism in the tar-producing province of Ostrobothnia may have been the reason for the witch-hunt wave that happened in this region during the late 17th century. The people were developing more expectations and plans for the future, and when these were not realized, they were quick to blame witches—according to a belief system the Lutheran church had imported from Germany.

The Empire had a colony in the New World in the modern-day Delaware-Pennsylvania area between 1638 and 1655. At least half of the immigrants were of Finnish origin.

The 17th century was an era of very strict Lutheran orthodoxy. In 1608, the law of Moses was declared the law of the land, in addition to secular legislation. Every subject of the realm was required to confess the Lutheran faith and church attendance was mandatory. Ecclesiastical penalties were widely used.[38] The rigorous requirements of orthodoxy were revealed in the dismissal of the Bishop of Turku, Johan Terserus, who wrote a catechism which was decreed heretical in 1664 by the theologians of the academy of Åbo.[39] On the other hand, the Lutheran requirement of the individual study of Bible prompted the first attempts at wide-scale education. The church required from each person a degree of literacy sufficient to read the basic texts of the Lutheran faith. Although the requirements could be fulfilled by learning the texts by heart, also the skill of reading became known among the population.[40]

In 1696–1699, a famine caused by climate decimated Finland. A combination of an early frost, the freezing temperatures preventing grain from reaching Finnish ports, and a lackluster response from the Swedish government saw about one-third of the population die.[41] Soon afterwards, another war determining Finland's fate began (the Great Northern War of 1700–21).

18th century

The Great Northern War (1700–1721) was devastating, as Sweden and Russia fought for control of the Baltic. Harsh conditions—worsening poverty and repeated crop failures—among peasants undermined support for the war, leading to Sweden's defeat. Finland was a battleground as both armies ravaged the countryside, leading to famine, epidemics, social disruption and the loss of nearly half the population. By 1721 only 250,000 remained.[43] Landowners had to pay higher wages to keep their peasants. Russia was the winner, annexing the south-eastern part, including the town of Viborg, after the Treaty of Nystad. The border with Russia came to lie roughly where it returned to after World War II. Sweden's status as a European great power was forfeited, and Russia was now the leading power in the North. The absolute monarchy ended in Sweden. During this Age of Liberty, the Parliament ruled the country, and the two parties of the Hats and Caps struggled for control leaving the lesser Court party, i.e. parliamentarians with close connections to the royal court, with little to no influence. The Caps wanted to have a peaceful relationship with Russia and were supported by many Finns, while other Finns longed for revenge and supported the Hats.

Finland by this time was depopulated, with a population in 1749 of 427,000. However, with peace the population grew rapidly, and doubled before 1800. 90% of the population were typically classified as peasants, most being free taxed yeomen. Society was divided into four Estates: peasants (free taxed yeomen), the clergy, nobility and burghers. A minority, mostly cottagers, were estateless, and had no political representation. Forty-five percent of the male population were enfranchised with full political representation in the legislature—although clerics, nobles and townsfolk had their own chambers in the parliament, boosting their political influence and excluding the peasantry on matters of foreign policy.

The mid-18th century was a relatively good time, partly because life was now more peaceful. However, during the Lesser Wrath (1741–1742), Finland was again occupied by the Russians after the government, during a period of Hat party dominance, had made a botched attempt to reconquer the lost provinces. Instead the result of the Treaty of Åbo was that the Russian border was moved further to the west. During this time, Russian propaganda hinted at the possibility of creating a separate Finnish kingdom.

Both the ascending Russian Empire and pre-revolutionary France aspired to have Sweden as a client state. Parliamentarians and others with influence were susceptible to taking bribes which they did their best to increase. The integrity and the credibility of the political system waned, and in 1771 the young and charismatic king Gustav III staged a coup d'état, abolished parliamentarism and reinstated royal power in Sweden—more or less with the support of the parliament. In 1788, he started a new war against Russia. Despite a couple of victorious battles, the war was fruitless, managing only to bring disturbance to the economic life of Finland. The popularity of King Gustav III waned considerably. During the war, a group of officers made the famous Anjala declaration demanding peace negotiations and calling of the Riksdag (Parliament). An interesting sideline to this process was the conspiracy of some Finnish officers, who attempted to create an independent Finnish state with Russian support. After an initial shock, Gustav III crushed this opposition. In 1789, the new constitution of Sweden strengthened the royal power further, as well as improving the status of the peasantry. However, the continuing war had to be finished without conquests—and many Swedes now considered the king as a tyrant.

With the interruption of the Gustav III's war (1788–1790), the last decades of the 18th century had been an era of development in Finland. New things were changing even everyday life, such as starting of potato farming after the 1750s. New scientific and technical inventions were seen. The first hot air balloon in Finland (and in the whole Swedish kingdom) was made in Oulu (Uleåborg) in 1784, only a year after it was invented in France. Trade increased and the peasantry was growing more affluent and self-conscious. The Age of Enlightenment's climate of broadened debate in the society on issues of politics, religion and morals would in due time highlight the problem that the overwhelming majority of Finns spoke only Finnish, but the cascade of newspapers, belles-lettres and political leaflets was almost exclusively in Swedish—when not in French.

The two Russian occupations had been harsh and were not easily forgotten. These occupations were a seed of a feeling of separateness and otherness, that in a narrow circle of scholars and intellectuals at the university in Turku was forming a sense of a separate Finnish identity representing the eastern part of the realm. The shining influence of the Russian imperial capital Saint Petersburg was also much stronger in southern Finland than in other parts of Sweden, and contacts across the new border dispersed the worst fears for the fate of the educated and trading classes under a Russian régime. At the turn of the 19th century, the Swedish-speaking educated classes of officers, clerics and civil servants were mentally well prepared for a shift of allegiance to the strong Russian Empire.

King Gustav III was assassinated in 1792, and his son Gustav IV Adolf assumed the crown after a period of regency. The new king was not a particularly talented ruler; at least not talented enough to steer his kingdom through the dangerous era of the French Revolution and Napoleonic wars.

Meanwhile, the Finnish areas belonging to Russia after the peace treaties in 1721 and 1743 (not including Ingria), called "Old Finland", were initially governed with the old Swedish laws (a not uncommon practice in the expanding Russian Empire in the 18th century). However, gradually the rulers of Russia granted large estates of land to their non-Finnish favorites, ignoring the traditional landownership and peasant freedom laws of Old Finland. There were even cases where the noblemen punished peasants corporally, for example by flogging. The overall situation caused decline in the economy and morale in Old Finland, worsened since 1797 when the area was forced to send men to the Imperial Army. The construction of military installations in the area brought thousands of non-Finnish people to the region. In 1812, after the Russian conquest of Finland, "Old Finland" was attached to the rest of the country, though the landownership question remained a serious problem until the 1870s.

Peasants

While the king of Sweden sent in his governor to rule Finland, in day to day reality the villagers ran their own affairs using traditional local assemblies (called the ting) which selected a local lagman, or lawman, to enforce the norms. The Swedes used the parish system to collect taxes. The socken (local parish) was at once a community religious organization and a judicial district that administered the king's law. The ting participated in the taxation process; taxes were collected by the bailiff, a royal appointee.[44]

In contrast to serfdom in Germany and Russia, the Finnish peasant was typically a freeholder who owned and controlled his small plot of land. There was no serfdom in which peasants were permanently attached to specific lands, and were ruled by the owners of that land. In Finland (and Sweden) the peasants formed one of the four estates and were represented in the parliament. Outside the political sphere, however, the peasants were considered at the bottom of the social order—just above vagabonds. The upper classes looked down on them as excessively prone to drunkenness and laziness, as clannish and untrustworthy, and especially as lacking honor and a sense of national spirit. This disdain dramatically changed in the 19th century when everyone idealised the peasant as the true carrier of Finnishness and the national ethos, as opposed to the Swedish-speaking elites.

The peasants were not passive; they were proud of their traditions and would band together and fight to uphold their traditional rights in the face of burdensome taxes from the king or new demands by the landowning nobility. The great Cudgel War in the south in 1596–1597 attacked the nobles and their new system of state feudalism; this bloody revolt was similar to other contemporary peasant wars in Europe.[45] In the north, there was less tension between nobles and peasants and more equality among peasants, due to the practice of subdividing farms among heirs, to non farm economic activities, and to the small numbers of nobility and gentry. Often the nobles and landowners were paternalistic and helpful. The Crown usually sided with the nobles, but after the "restitution" of the 1680s it ended the practice of the nobility extracting labor from the peasants and instead began a new tax system whereby royal bureaucrats collected taxes directly from the peasants, who disliked the efficient new system. After 1800 growing population pressure resulted in larger numbers of poor crofters and landless laborers and the impoverishment of small farmers.[46]

Historical population of Finland

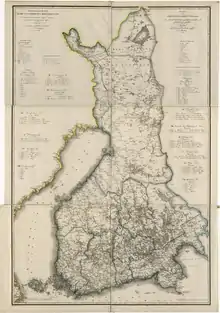

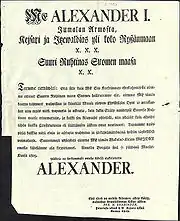

Grand Duchy of Finland

.jpg.webp)

During the Finnish War between Sweden and Russia, Finland was again conquered by the armies of Tsar Alexander I. The four Estates of occupied Finland were assembled at the Diet of Porvoo on 29 March 1809, to pledge allegiance to Alexander I of Russia. Following the Swedish defeat in the war and the signing of the Treaty of Fredrikshamn on 17 September 1809, Finland remained a Grand Duchy in the Russian Empire until the end of 1917, with the czar as Grand Duke. Russia assigned Karelia ("Old Finland") to the Grand Duchy in 1812. During the years of Russian rule the degree of autonomy varied. Periods of censorship and political prosecution occurred, particularly in the two last decades of Russian control, but the Finnish peasantry remained free (unlike the Russian serfs) as the old Swedish law remained effective (including the relevant parts from Gustav III's Constitution of 1772). The old four-chamber Diet was re-activated in the 1860s agreeing to supplementary new legislation concerning internal affairs. In addition, Finns remained free of obligations connected to the empire, such as the duty to serve in tsarist armies, and they enjoyed certain rights that citizens from other parts of the empire did not have.[50]

Economy

.jpg.webp)

Before 1860 overseas merchant firms and the owners of landed estates had accumulated wealth that became available for industrial investments. After 1860 the government liberalized economic laws and began to build a suitable physical infrastructure of ports, railroads and telegraph lines. The domestic market was small but rapid growth took place after 1860 in export industries drawing on forest resources and mobile rural laborers. Industrialization began during the mid-19th century from forestry to industry, mining and machinery and laid the foundation of Finland's current day prosperity, even though agriculture employed a relatively large part of the population until the post–World War II era.

The beginnings of industrialism took place in Helsinki. Alfred Kihlman (1825–1904) began as a Lutheran priest and director of the elite Helsingfors boys' school, the Swedish Normal Lyceum. He became a financier and member of the diet. There was little precedent in Finland in the 1850s for raising venture capital. Kihlman was well connected and enlisted businessmen and capitalists to invest in new enterprises. In 1869, he organized a limited partnership that supported two years of developmental activities that led to the founding of the Nokia company in 1871.[51]

After 1890 industrial productivity stagnated because entrepreneurs were unable to keep up with technological innovations made by competitors in Germany, Britain and the United States. However, Russification opened up a large Russian market especially for machinery.

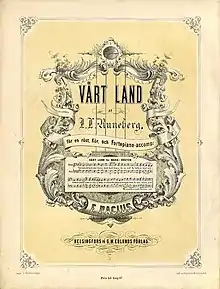

Nationalism

The Finnish national awakening in the mid-19th century was the result of members of the Swedish-speaking upper classes deliberately choosing to promote Finnish culture and language as a means of nation building, i.e. to establish a feeling of unity among all people in Finland including (and not of least importance) between the ruling elite and the ruled peasantry. The publication in 1835 of the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala, a collection of traditional myths and legends which is the folklore of the Karelian people (the Finnic Eastern Orthodox people who inhabit the Lake Ladoga-region of eastern Finland and present-day NW Russia), stirred the nationalism that later led to Finland's independence from Russia.

Particularly following Finland's incorporation into the Swedish central administration during the 16th and 17th centuries, Swedish was spoken by about 15% of the population, especially the upper and middle classes. Swedish was the language of administration, public institutions, education and cultural life. Only the peasants spoke Finnish. The emergence of Finnish to predominance resulted from a 19th-century surge of Finnish nationalism, aided by Russian bureaucrats attempting to separate Finns from Sweden and to ensure the Finns' loyalty.[52]

In 1863, the Finnish language gained an official position in administration. In 1892 Finnish finally became an equal official language and gained a status comparable to that of Swedish. Nevertheless, the Swedish language continued to be the language of culture, arts and business all the way to the 1920s.

Movements toward Finnish national pride, as well as liberalism in politics and economics involved ethnic and class dimensions. The nationalist movement against Russia began with the Fennoman movement led by Hegelian philosopher Johan Vilhelm Snellman in the 1830s. Snellman sought to apply philosophy to social action and moved the basis of Finnish nationalism to establishment of the language in the schools, while remaining loyal to the czar. Fennomania became the Finnish Party in the 1860s.[53]

Liberalism was the central issue of the 1860s to 1880s. The language issue overlapped both liberalism and nationalism, and showed some a class conflict as well, with the peasants pitted against the conservative Swedish-speaking landowners and nobles. Finnish activists divided themselves into "old" (no compromise on the language question and conservative nationalism) and "young" (liberation from Russia) Finns. The leading liberals were Swedish-speaking intellectuals who called for more democracy; they became the radical leaders after 1880. The liberals organized for social democracy, labor unions, farmer cooperatives, and women's rights.[54]

Nationalism was contested by the pro-Russian element and by the internationalism of the labor movement. The result was a tendency to class conflict over nationalism, but the early 1900s the working classes split into the Valpas (class struggle emphasis) and Mäkelin (nationalist emphasis).[55]

Religion

During that period Lutheranism and Eastern Orthodoxy were official religions of the Finnish Grand Duchy. The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland was separated from Church of Sweden in the early 19th century. Immediately after the Finnish War, Finnish Lutheran clergy feared state-led proselytism to Orthodoxy. The majority of Finns were Lutheran Christians, but an ancient prominent Orthodox minority lived in Karelian Isthmus and Ladoga Karelia. The monasteries of Valaam and Konevets were important religious centres and pilgrimage sites of Orthodox faithful. There were also Orthodox churches built in Finnish cities and towns, where there were Russian garrisons. During this period, Roman Catholism, Judaism and Islam came to Finland with Russian soldiers and merchants.

While the vast majority of Finns were Lutheran, there were two strains to Lutheranism that eventually merged to form the modern Finnish church. On the one hand was the high-church emphasis on ritual, with its roots in traditional peasant collective society. Paavo Ruotsalainen (1777–1852) on the other hand was a leader of the new pietism, with its subjectivity, revivalism, emphasis on personal morality, lay participation, and the social gospel. The pietism appealed to the emerging middle class. The Ecclesiastical Law of 1869 combined the two strains. Finland's political and Lutheran leaders considered both Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism to be threats to the emerging nation. Eastern Orthodoxy was rejected as a weapon of Russification, while anti-Catholicism was long-standing. Anti-Semitism was also a factor, so the Dissenter Law of 1889 upgraded the status only of the minor Protestant sects.[56] Founding monasteries was forbidden.

Music

Before 1790 music was found in Lutheran churches and in folk traditions.[57] In 1790 music lovers founded the Åbo Musical Society; it gave the first major stimulus to serious music by Finnish composers. In the 1880s, new institutions, especially the Helsinki Music Institute (since 1939 called the Sibelius Academy), the Institute of Music of Helsinki University and the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, integrated Finland into the mainstream of European music. By far the most influential composer was Jean Sibelius (1865–1957); he composed nearly all his music before 1930.[58] In April 1892 Sibelius presented his new symphony Kullervo in Helsinki. It featured poetry from the Kalevala, and was celebrated by critics as truly Finnish music.[59]

Politics

Despite certain freedoms granted to Finland, the Grand Duchy was not a democratic state. The tsar retained supreme power and ruled through the highest official in the land, the governor general, almost always a Russian officer. Alexander dissolved the Diet of the Four Estates shortly after convening it in 1809, and it did not meet again for half a century. The tsar's actions were in accordance with the royalist constitution Finland had inherited from Sweden. The Finns had no guarantees of liberty, but depended on the tsar's goodwill for any freedoms they enjoyed. When Alexander II, the Tsar Liberator, convened the Diet again in 1863, he did so not to fulfill any obligation but to meet growing pressures for reform within the empire as a whole. In the remaining decades of the century, the Diet enacted numerous legislative measures that modernized Finland's system of law, made its public administration more efficient, removed obstacles to commerce, and prepared the ground for the country's independence in the next century.[50]

Russification

The policy of Russification of Finland (1899–1905 and 1908–1917, called sortokaudet/sortovuodet ('times/years of oppression') in Finnish) was the policy of the Russian czars designed to limit the special status of the Grand Duchy of Finland and more fully integrate it politically, militarily, and culturally into the empire.[60] Finns were strongly opposed and fought back by passive resistance and a strengthening of Finnish cultural identity.[61] Key provisions were, first, the February Manifesto of 1899 which asserted the imperial government's right to rule Finland without the consent of local legislative bodies; second, the Language Manifesto of 1900 which made Russian the language of administration of Finland; and third, the conscription law of 1901 which incorporated the Finnish army into the imperial army and sent conscripts away to Russian training camps.[62]

Democratic change

In 1906, as a result of the Russian Revolution of 1905 and the associated Finnish general strike of 1905, the old four-chamber Diet was replaced by a unicameral Parliament of Finland (the Eduskunta). For the first time in Europe, universal suffrage (right to vote) and eligibility was implemented to include women: Finnish women were the first in Europe to gain full eligibility to vote; and have membership in an estate; land ownership or inherited titles were no longer required. However, on the local level things were different, as in the municipal elections the number of votes was tied to amount of tax paid. Thus, rich people could cast a number of votes, while the poor perhaps none at all. The municipal voting system was changed to universal suffrage in 1917 when a left-wing majority was elected to Parliament.

Emigration trends

Emigration was especially important 1890–1914,[63] with many young men and some families headed to Finnish settlements in the United States, and also to Canada. They typically worked in lumber and mining, and many were active in Marxist causes on the one hand, or the Finnish Evangelical Lutheran Church of America on the other. In the 21st century about 700,000 Americans and 140,000 Canadians claim Finnish ancestry.

- 1880s: 26,000

- 1890s: 59,000

- 20th century: 159,000

- 1910s: 67,000

- 1920s: 73,000

- 1930s: 3,000

- 1940s: 7,000

- 1950s: 32,000

By 2000 about 6% of the population spoke Swedish as their first language, or 300,000 people. However, since the late 20th century there has been a steady migration of older, better educated Swedish speakers to Sweden.[64]

Independence and Civil War

In the aftermath of the February Revolution in Russia, Finland received a new Senate, and a coalition Cabinet with the same power distribution as the Finnish Parliament. Based on the general election in 1916, the Social Democrats had a small majority, and the Social Democrat Oskari Tokoi became prime minister. The new Senate was willing to cooperate with the Provisional government of Russia, but no agreement was reached. Finland considered the personal union with Russia to be over after the dethroning of the Tsar—although the Finns had de facto recognized the Provisional government as the Tsar's successor by accepting its authority to appoint a new Governor General and Senate. They expected the Tsar's authority to be transferred to Finland's Parliament, which the Provisional government refused, suggesting instead that the question should be settled by the Russian Constituent Assembly.

For the Finnish Social Democrats it seemed as though the bourgeoisie was an obstacle on Finland's road to independence as well as on the proletariat's road to power. The non-Socialists in Tokoi's Senate were, however, more confident. They, and most of the non-Socialists in the Parliament, rejected the Social Democrats' proposal on parliamentarism (the so-called "Power Act") as being too far-reaching and provocative. The act restricted Russia's influence on domestic Finnish matters, but did not touch the Russian government's power on matters of defence and foreign affairs. For the Russian Provisional government this was, however, far too radical, exceeding the Parliament's authority, and so the Provisional government dissolved the Parliament.

The minority of the Parliament, and of the Senate, were content. New elections promised a chance for them to gain a majority, which they were convinced would improve the chances to reach an understanding with Russia. The non-Socialists were also inclined to cooperate with the Russian Provisional Government because they feared the Social Democrats' power would grow, resulting in radical reforms, such as equal suffrage in municipal elections, or a land reform. The majority had the completely opposite opinion. They did not accept the Provisional government's right to dissolve the Parliament.

The Social Democrats held on to the Power Act and opposed the promulgation of the decree of dissolution of the Parliament, whereas the non-Socialists voted for promulgating it. The disagreement over the Power Act led to the Social Democrats leaving the Senate. When the Parliament met again after the summer recess in August 1917, only the groups supporting the Power Act were present. Russian troops took possession of the chamber, the Parliament was dissolved, and new elections were held. The result was a (small) non-Socialist majority and a purely non-Socialist Senate. The suppression of the Power Act, and the cooperation between Finnish non-Socialists and Russia provoked great bitterness among the Socialists, and had resulted in dozens of politically motivated attacks and murders.

Independence

The October Revolution of 1917 turned Finnish politics upside down. Now, the new non-Socialist majority of the Parliament desired total independence, and the Socialists came gradually to view Soviet Russia as an example to follow. On 15 November 1917, the Bolsheviks declared a general right of self-determination "for the Peoples of Russia", including the right of complete secession. On the same day the Finnish Parliament issued a declaration by which it temporarily took power in Finland.

Worried by developments in Russia and Finland, the non-Socialist Senate proposed that Parliament declare Finland's independence, which was voted by the Parliament on 6 December 1917. On 18 December (31 December N. S.) the Soviet government issued a Decree, recognizing Finland's independence, and on 22 December (4 January 1918 N. S.) it was approved by the highest Soviet executive body (VTsIK). Germany and the Scandinavian countries followed without delay.

Civil war

Finland after 1917 was bitterly divided along social lines. The Whites consisted of the Swedish-speaking middle and upper classes and the farmers and peasantry who dominated the northern two-thirds of the land. They had a conservative outlook and rejected socialism. The Socialist-Communist Reds comprised the Finnish-speaking urban workers and the landless rural cottagers. They had a radical outlook and rejected capitalism.[65]

From January to May 1918, Finland experienced the brief but bitter Finnish Civil War. On one side there were the "white" civil guards, who fought for the anti-Socialists. On the other side were the Red Guards, which consisted of workers and tenant farmers. The latter proclaimed a Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic. World War I was still underway and the defeat of the Red Guards was achieved with support from Imperial Germany, while Sweden remained neutral and Russia withdrew its forces. The Reds lost the war and the White peasantry rose to political leadership in the 1920s–1930s. About 37,000 men died, most of them in prisoner camps ravaged by influenza and other diseases.

Finland in the inter-war era

After the civil war, the parliament controlled by the Whites voted to establish a constitutional monarchy to be called the Kingdom of Finland, with German prince Frederick Charles of Hesse as king. However, Germany's defeat in November 1918 made the plan impossible and Finland instead became a republic, with Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg elected as its first President in 1919. Despite the bitter civil war, and repeated threats from fascist movements, Finland became and remained a capitalist democracy under the rule of law. By contrast, nearby Estonia, in similar circumstances but without a civil war, started as a democracy and was turned into a dictatorship in 1934.[66]

Agrarian reform

Large scale agrarian reform in the 1920s involved breaking up the large estates controlled by the old nobility and selling the land to ambitious peasants. The farmers became strong supporters of the government.[67]

Diplomacy

Finland became member of the League of Nations on 16 December 1920.[68] The new republic faced a dispute over the Åland Islands, which were overwhelmingly Swedish-speaking and sought retrocession to Sweden. However, as Finland was not willing to cede the islands, they were offered an autonomous status. Nevertheless, the residents did not approve the offer, and the dispute over the islands was submitted to the League of Nations. The League decided that Finland should retain sovereignty over the Åland Islands, but they should be made an autonomous province. Thus Finland was under an obligation to ensure the residents of Åland a right to maintain the Swedish language, as well as their own culture and local traditions. At the same time, an international treaty was concluded on the neutral status of Åland, under which it was prohibited to place military headquarters or forces on the islands.

Prohibition

Alcohol abuse had a long history, especially regarding binge drinking and public intoxication, which became a crime in 1733. In the 19th century the punishments became stiffer and stiffer, but the problem persisted. A strong abstinence movement emerged that cut consumption in half from the 1880s to the 1910s, and gave Finland the lowest drinking rate in Europe. Four attempts at instituting prohibition of alcohol during the Grand Duchy period were rejected by the czar; with the czar gone Finland enacted prohibition in 1919. Smuggling emerged and enforcement was slipshod. Criminal convictions for drunkenness went up by 500%, and violence and crime rates soared. Public opinion turned against the law, and a national plebiscite went 70% for repeal, so prohibition was ended in early 1932.[69][70]

Politics

Nationalist sentiment remaining from the Civil War developed into the proto-Fascist Lapua Movement in 1929. Initially the movement gained widespread support among anti-Communist Finns, but following a failed coup attempt in 1932 it was banned and its leaders imprisoned.[71]

Relations with Soviet Union

In the wake of the Civil War there were many incidents along the border between Finland and Soviet Russia, such as the Aunus expedition and the Pork mutiny. Relations with the Soviets were improved after the Treaty of Tartu in 1920, in which Finland gained Petsamo, but gave up its claims on East Karelia.

Tens of thousands of radical Finns—from Finland, the United States and Canada—took up Stalin's 1923 appeal to create a new Soviet society in the Karelian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (KASSR), a part of Russia. Most were executed in the purges of the 1930s.[72]

The Soviet Union started to tighten its policy against Finland in the 1930s, limiting the navigation of Finnish merchant ships between Lake Ladoga and the Gulf of Finland and blocking it totally in 1937.

Finland in the Second World War

.jpg.webp)

In August 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, where Finland and the Baltic states were allocated to the Soviet "sphere of influence". After invading Poland, the Soviet Union sent ultimatums to the Baltic countries, where it demanded military bases on their soil. The Baltic states accepted Soviet demands, and lost their independence in the summer of 1940. In October 1939, the Soviet Union sent a similar request to Finland, but the Finns refused these demands.

The Soviet Union invaded Finland on 30 November 1939, launching the Winter War, with the aim of annexing Finland into the Soviet Union.[73] The Finnish Democratic Republic was established by Joseph Stalin at the beginning of the war with the purpose of governing Finland after Soviet conquest.[74] The Red Army was defeated in numerous battles, notably at the Battle of Suomussalmi. After two months of negligible progress on the battlefield, as well as severe losses of men and materiel, the Soviets put an end to the Finnish Democratic Republic in late January 1940 and recognized the legal Finnish government as the legitimate government of Finland.[75] Soviet forces began to make progress in February and reached Vyborg in March. Fighting came to an end on 13 March 1940 with the signing of the Moscow Peace Treaty. Finland had successfully defended its independence, but ceded 9% of its territory to the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union was expelled from the League of Nations as a result of the invasion.

After the Winter War the Finnish Army was exhausted and needed recovery and support as soon as possible. The United Kingdom declined to help, but in autumn 1940, Nazi Germany offered weapon deals to Finland if the Finnish government would allow German troops to travel through Finland to German-occupied Norway. Finland accepted, weapons deals were made, and military co-operation began in December 1940.[76]

Hostilities resumed in June 1941 with the start of the Continuation War, when Finland aligned with Germany following Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union. Finland was involved with the Siege of Leningrad and occupied East Karelia from 1941 to 1944. This irredentist sentiment of a Greater Finland, whose inhabitants were culturally related to the Finnish people, although Eastern Orthodox by religion, resulted in other countries being considerably less sympathetic to the Finnish cause.

Finnish forces won several decisive battles during the Soviet Vyborg–Petrozavodsk offensive of 1944, including the Battle of Tali-Ihantala and the Battle of Ilomantsi. These victories helped ensure Finnish independence, and led to the Moscow Armistice with the Soviet Union. The armistice called for the expulsion of German troops residing in northern Finland, leading to the Lapland War whereby the Finns forced the Germans to withdraw into Norway (then under German occupation).[77][78]

Finland was never occupied by Soviet forces. Its army of over 600,000 soldiers saw only 3,500 prisoners of war. About 96,000 Finns died, or 2.5% of a population of 3.8 million; civilian casualties were under 2,500.[79] Finland managed to defend its democracy, contrary to most other countries within the Soviet sphere of influence, and suffered comparably limited losses in terms of civilian lives and property. It was, however, punished harsher than other German co-belligerents and allies, having to pay large reparations and resettle an eighth of its population after having lost an eighth of its territory, including the major city of Viipuri.[80] After the war, the Soviet government settled these gained territories with people from many different regions of the USSR, for instance from Ukraine.

The Finnish government did not participate in the systematic killing of Jews, although the country remained a "co-belligerent", a de facto ally of Germany until 1944. In total, eight German Jewish refugees were handed over to the German authorities. In the Tehran Conference of 1942, the leaders of the Allies agreed that Finland was fighting a separate war against the Soviet Union, and that in no way was it hostile to the Western allies. The Soviet Union was the only Allied country against which Finland had conducted military operations. Unlike any of the Axis nations, Finland was a parliamentary democracy throughout the 1939–1945 period. The commander of Finnish armed forces during the Winter War and the Continuation War, Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim, became the President of Finland at the very end of the Continuation War. Finland made a separate armistice agreement with the Soviet Union on 19 September 1944, and was the only bordering country of USSR in Europe (alongside Norway, which gained a border with the Soviet Union only after the war) that kept its independence after the war.

During and in between the wars, approximately 80,000 Finnish war-children were evacuated abroad: 5% went to Norway, 10% to Denmark, and the rest to Sweden. Most of the children were sent back by 1948, but 15–20% remained abroad.

The Moscow Armistice was signed between Finland on one side and the Soviet Union and Britain on the other side on 19 September 1944, ending the Continuation War. The armistice compelled Finland to drive German troops from its territory, leading to the Lapland War 1944–1945.

In 1947, Finland reluctantly declined Marshall aid in order to preserve good relations with the Soviets, ensuring Finnish autonomy.[81] Nevertheless, the United States shipped secret development aid and financial aid to the non-communist SDP (Social Democratic Party).[82] Establishing trade with the Western powers, such as Britain, and the reparations to the Soviet Union caused Finland to transform itself from a primarily agrarian economy to an industrialised one. After the reparations had been paid off, Finland continued to trade with the Soviet Union in the framework of bilateral trade.

Finland's role in the Second World War was unusual in several ways. Despite massive superiority in military strength, the Soviet Union was unable to conquer Finland when the former invaded in 1939. In late 1940, German-Finnish co-operation began; it took a form that was unique when compared to relations with the Axis. Finland signed the Anti-Comintern Pact, which made Finland an ally with Germany in the war against the Soviet Union. But, unlike all other Axis states, Finland never signed the Tripartite Pact, meaning that Finland was not de jure an Axis nation.

Memorials

Although Finland lost territory in both of its wars with the Soviets, the memory of these wars was sharply etched in the national consciousness. Finland celebrates these wars as a victory for the Finnish national spirit, which survived against long odds and allowed Finland to maintain its independence. Many groups of Finns are commemorated today, including not just fallen soldiers and veterans, but also orphans, evacuees from Karelia, the children who were evacuated to Sweden, women who worked during the war at home or in factories, and the veterans of the women's defense unit Lotta Svärd.

Some of these groups could not be properly commemorated until long after the war ended in order to preserve good relations with the Soviet Union. However, after a long political campaign backed by survivors of what Finns call the Partisan War, the Finnish Parliament passed legislation establishing compensation for the war's victims.[83][84]

Post WW2 and Cold War

Neutrality in Cold War

Finland retained a democratic constitution and free economy during the Cold War era. Treaties signed in 1947 and 1948 with the Soviet Union included obligations and restraints on Finland, as well as territorial concessions. The Paris Peace Treaty (1947) limited the size and the nature of Finland's armed forces. Weapons were to be solely defensive. A deepening of postwar tensions led a year later to the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance (1948) with the Soviet Union. The latter, in particular, was the foundation of Finno-Soviet relations in the postwar era. Under the terms of the treaty, Finland was bound to confer with the Soviets and perhaps to accept their aid if an attack from Germany, or countries allied with Germany, seemed likely. The treaty prescribed consultations between the two countries, but it had no mechanism for automatic Soviet intervention in a time of crisis.[50] Both treaties have been abrogated by Finland since the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union, while leaving the borders untouched. Even though being a neighbor to the Soviet Union sometimes resulted in overcautious concern in foreign policy ("Finlandization"), Finland developed closer co-operation with the other Nordic countries and declared itself neutral in superpower politics.

The Finnish post-war president, Juho Kusti Paasikivi, a leading conservative politician, saw that an essential element of Finnish foreign policy must be a credible guarantee to the Soviet Union that it need not fear attack from, or through, Finnish territory. Because a policy of neutrality was a political component of this guarantee, Finland would ally itself with no one. Another aspect of the guarantee was that Finnish defenses had to be sufficiently strong to defend the nation's territory. This policy remained the core of Finland's foreign relations for the rest of the Cold War era.[50]

In 1952, Finland and the countries of the Nordic Council entered into a passport union, allowing their citizens to cross borders without passports and soon also to apply for jobs and claim social security benefits in the other countries. Many from Finland used this opportunity to secure better-paying jobs in Sweden in the 1950s and 1960s, dominating Sweden's first wave of post-war labour immigrants. Although Finnish wages and standard of living could not compete with wealthy Sweden until the 1970s, the Finnish economy rose remarkably from the ashes of World War II, resulting in the buildup of another Nordic-style welfare state.

.jpg.webp)

Despite the passport union with Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Iceland, Finland could not join the Nordic Council until 1955 because of Soviet fears that Finland might become too close to the West. At that time the Soviet Union saw the Nordic Council as part of NATO of which Denmark, Norway and Iceland were members. That same year Finland joined the United Nations, though it had already been associated with a number of UN specialized organisations.[85] The first Finnish ambassador to the UN was G.A. Gripenberg (1956–1959), followed by Ralph Enckell (1959–1965), Max Jakobson (1965–1972), Aarno Karhilo (1972–1977), Ilkka Pastinen (1977–1983), Keijo Korhonen (1983–1988), Klaus Törnudd (1988–1991), Wilhelm Breitenstein (1991–1998) and Marjatta Rasi (1998–2005). In 1972 Max Jakobson was a candidate for Secretary-General of the UN. In another remarkable event of 1955, the Soviet Union decided to return the Porkkala peninsula to Finland, which had been rented to the Soviet Union in 1948 for 50 years as a military base, a situation which somewhat endangered Finnish sovereignty and neutrality.

Officially claiming to be neutral, Finland lay in the grey zone between the Western countries and the Soviet Union, and it also developed into one of the centres of the East-West espionage, in which both the KGB and the CIA played their parts.[86][87][88][89][90] The 1949 established Finnish Security Intelligence Service (SUPO, Suojelupoliisi), an operational security authority and a police unit under the Interior Ministry, whose core areas of activity are counter-Intelligence, counter-terrorism and national security,[91] also participated in this activity in some places.[92][93] The Finno-Soviet Treaty of 1948 (Finno-Soviet Pact of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance) gave the Soviet Union some leverage in Finnish domestic politics. However, Finland maintained capitalism unlike most other countries bordering the Soviet Union. Property rights were strong. While nationalization committees were set up in France and UK, Finland avoided nationalizations. After failed experiments with protectionism in the 1950s, Finland eased restrictions and committed to a series of international free trade agreements: first an associate membership in the European Free Trade Association in 1961, a full membership in 1986 and also an agreement with the European Community in 1973. Local education markets expanded and an increasing number of Finns also went abroad to study in the United States or Western Europe, bringing back advanced skills. There was a quite common, but pragmatic-minded, credit and investment cooperation by state and corporations, though it was considered with suspicion. Support for capitalism was widespread.[94] Savings rate hovered among the world's highest, at around 8% until the 1980s. In the beginning of the 1970s, Finland's GDP per capita reached the level of Japan and the UK. Finland's economic development shared many aspects with export-led Asian countries.[94]

Building on its status as western democratic country with friendly ties with the Soviet Union, Finland pushed to reduce the political and military tensions of cold war. Since the 1960s, Finland urged the formation of a Nordic Nuclear Weapons Free Zone (Nordic NWFZ), and in 1972–1973 was the host of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE), which culminated in the signing of the Helsinki Accords in 1975 and lead to the creation of the OSCE.[50]

Society and the welfare state

Before 1940 Finland was a poor rural nation of urban and rural workers and independent farmers. There was a small middle class, employed chiefly as civil servants and in small local businesses. As late as 1950 half of the workers were in agriculture and only a third lived in urban towns.[95] The new jobs in manufacturing, services and trade quickly attracted people to the towns and cities. The average number of births per woman declined from a baby boom peak of 3.5 in 1947 to 1.5 in 1973.[95] When baby boomers entered the workforce, the economy did not generate jobs fast enough and hundreds of thousands emigrated to the more industrialized Sweden, migration peaking in 1969 and 1970 (today 4.7 percent of Swedes speak Finnish).[95]

By the 1990s, farm laborers had nearly all moved on, leaving owners of small farms. By 2000 the social structure included a politically active working class, a primarily clerical middle class, and an upper bracket consisting of managers, entrepreneurs, and professionals. The social boundaries between these groups were not distinct. Causes of change included the growth of a mass culture, international standards, social mobility, and acceptance of democracy and equality as typified by the welfare state.[96]

The generous system of welfare benefits emerged from a long process of debate, negotiations and maneuvers between efficiency-oriented modernizers on the one hand and Social Democrats and labor unions. A compulsory system provides old-age and disability insurance.[97] The national government provides unemployment insurance, maternity benefits, family allowances, and day-care centers. Health insurance covers most of the cost of outpatient care. The national health act of 1972 provided for the establishment of free health centers in every municipality.[98] There were major cutbacks in the early 1990s, but they were distributed to minimize the harm to the vast majority of voters.[99]

Economy

The post-war period was a time of rapid economic growth and increasing social and political stability for Finland. The five decades after the Second World War saw Finland turn from a war-ravaged agrarian society into one of the most technologically advanced countries in the world, with a sophisticated market economy and high standard of living.

In 1991, Finland fell into a depression caused by a combination of economic overheating, fixed currency, depressed Western, Soviet, and local markets. Stock market and housing prices declined by 50%.[100] The growth in the 1980s was based on debt and defaults started rolling in. GDP declined by 15% and unemployment increased from a virtual full employment to one fifth of the workforce. The crisis was amplified by trade unions' initial opposition to any reforms.[101] Politicians struggled to cut spending and the public debt doubled to around 60% of GDP.[100] Some 7–8% of GDP was needed to bail out failing banks and force banking sector consolidation.[102] After devaluations the depression bottomed out in 1993.

Post Cold War History

The GDP growth rate has since been one of the highest of OECD countries and Finland has topped many indicators of national performance.

Until 1991, President Mauno Koivisto and two of the three major parties, Center Party and the Social Democrats opposed the idea of European Union membership and preferred entering into the European Economic Area treaty.[103] However, after Sweden had submitted its membership application in 1991 and the Soviet Union was dissolved at the end of the year, Finland submitted its own application to the EU in March 1992. The accession process was marked by heavy public debate, where the differences of opinion did not follow party lines. Officially, all three major parties were supporting the Union membership, but members of all parties participated in the campaign against the membership. Before the parliamentary decision to join the EU, a consultative referendum was held on 16 April 1994, in which 56.9% of the votes were in favour of joining. The process of accession was completed on 1 January 1995, when Finland joined the European Union along with Austria and Sweden. Leading Finland into the EU is held as the main achievement of the Centrist-Conservative government of Esko Aho then in power. In the economic policy, the EU membership brought with it many large changes. While politicians were previously involved in setting interest rates, the Bank of Finland was given an inflation-targeting mandate until Finland joined the eurozone.[100] During Prime Minister Paavo Lipponen's two successive governments 1995–2003, several large state companies were privatized fully or partially.[104] Matti Vanhanen's two cabinets followed suit until autumn 2008, when the state became a major shareholder in the Finnish telecom company Elisa with the intention to secure the Finnish ownership of a strategically important industry.

In addition to fast integration with the European Union, safety against Russian leverage has been increased by building fully NATO-compatible military. 1000 troops (a high per-capita amount) are simultaneously committed in NATO and UN operations. Finland has also opposed energy projects that increase dependency on Russian imports.[105] For a long time, Finland remained one of the last non-NATO members in Europe, without enough support for full membership unless Sweden joined first.[106]

On 24 February 2022, the Russian president Vladimir Putin ordered the Russian Armed Forces to begin the invasion of Ukraine. On 25 February, a Russian Foreign Ministry spokesperson threatened Finland and Sweden with "military and political consequences" if they attempted to join NATO, which neither were actively seeking.[107] After the invasion public support for membership rose significantly.[4]

On 4 April 2023, the last NATO members ratified Finland's application to join the alliance, making Finland the 31st member.[108]

See also

- Diplomatic history of World War II#Finland

- Early Finnish wars

- Finns

- Finland–Russia relations

- Finland under Swedish rule

- Henrik Gabriel Porthan

- Kvenland

- List of Finnish treaties

- List of presidents of Finland

- List of prime ministers of Finland

- List of wars involving Finland

- Military history of Finland

- Monarchy of Finland

- Politics of Finland

- Timeline of Finnish history

References

- Georg Haggren, Petri Halinen, Mika Lavento, Sami Raninen ja Anna Wessman (2015). Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Helsinki: Gaudeamus. p. 339. ISBN 9789524953634.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Georg Haggren, Petri Halinen, Mika Lavento, Sami Raninen ja Anna Wessman (2015). Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Helsinki: Gaudeamus. p. 369. ISBN 978-952-495-363-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Poll: Finnish support for Nato membership still low". December 2016. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- "Ylen kysely: Nato-jäsenyyden kannatus vahvistuu – 62 prosenttia haluaa nyt Natoon". March 2022. Archived from the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- KM 11708 Kiuruveden kirves; Esinekuva (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 31 December 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- Kristiinankaupungin Susiluola ((archived))

- Georg Haggren, Petri Halinen, Mika Lavento, Sami Raninen ja Anna Wessman (2015). Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Gaudeamus. p. 25. ISBN 9789524953634.