History of Kosovo

The history of Kosovo dates back to pre-historic times when the Starčevo culture, Vinča culture, Bubanj-Hum culture, and Baden culture were active in the region. Since then, many archaeological sites have been discovered due to the abundance of natural resources which gave way to the development of life.

| History of Kosovo |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Kosovo |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Mythology and Folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Sport |

| Monuments |

In antiquity the area was part of the Kingdom of Dardania. It was annexed by the Roman Empire toward the end of the 1st century BC and incorporated into the province of Moesia. In the Middle Ages, the region became part of the Bulgarian Empire, the Byzantine Empire and the Serbian mediaeval states. In 1389 the Battle of Kosovo was fought between a coalition of Balkan states and the Ottoman Empire, resulting in a Serbian decline and eventual Ottoman conquest in 1459.

Kosovo's modern history can be traced to the Ottoman Sanjak of Prizren, of which parts were organised into Kosovo Vilayet in 1877. This was when Kosovo was used as the name of the entire territory for the first time. In 1913 the Kosovo Vilayet was incorporated into the Kingdom of Serbia, which in 1918 formed Yugoslavia. Kosovo gained autonomy in 1963 under Josip Broz Tito's direction. This autonomy was significantly extended by Yugoslavia's 1974 Constitution, but was lost in 1990. In 1999 UNMIK stepped in. On 17 February 2008, representatives of the people of Kosovo[1] unilaterally declared Kosovo's independence and subsequently adopted the Constitution of Republic of Kosovo, which came into effect on 15 June 2008.

Prehistory

In prehistory, the succeeding Starčevo culture, Vinča culture, Bubanj-Hum culture, Baden culture were active in the region.[2] The area in and around Kosovo has been inhabited for nearly 10,000 years. During the Neolithic age, Kosovo lay within the areal of the Vinča-Turdaş culture which is characterised by West Balkan black and grey pottery. Bronze and Iron Age tombs have been found in Rrafshi i Dukagjinit.[3]

The favourable Geo-strategic position, as well as abundant natural resources, were ideal for the development of life since the prehistoric periods, proven by hundreds of archaeological sites discovered and identified throughout Kosovo, which proudly present its rich archaeological heritage.[4] The number of sites with archaeological potential is increasing, this as a result of findings and investigations that are carried out throughout Kosovo but also from many superficial traces which offer a new overview of antiquity of Kosovo.[4]

The earliest traces documented in the territory of Kosovo belong to the Stone Age Period, namely there are indications that cave dwellings might have existed like for example the Radivojce Cave set near the spring of the Drin river, then there are some indications at Grnčar Cave in the Viti municipality, Dema and Karamakaz Caves of Peja and others. However, life during the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age is not confirmed yet and not scientifically proven. Therefore, until arguments of Paleolithic and Mesolithic man are confirmed, Neolithic man, respectively the Neolithic sites are considered as the chronological beginning of population in Kosovo. From this period until today Kosovo has been inhabited, and traces of activities of societies from prehistoric, ancient and up to mediaeval time are visible throughout its territory, whereas, in some archaeological sites, multilayer settlements clearly reflect the continuity of life through centuries.[5]

Vlashnjë and Runik are two of the most significant Neolithic sites which have been found and excavated in a series of expeditions. Vlashnjë is a multi-layered settlement and site area. Archaeological excavations have identified habitation and use of the area since the Neolithic era. The rock art paintings at Mrrizi i Kobajës (late Neolithic-early Bronze Age) are the first find of prehistoric rock art in Kosovo. In late antiquity, Vlashnja was a fortified settlement part of the fortification network which Justinian I rebuilt along the White Drin in Dardania. Crkvina near Miokovci, Serbia and Runik have been identified as the two oldest settlements of the Starčevo culture. They are statistically indistinguishable to each other and have been dated to ca. 6238 BC (6362–6098 BC at 95% CI) and ca. 6185 BC (6325–6088 BC at 95% Cl).[6]

Antiquity

During the Neolithic age, Kosovo lay within the area of the Vinča-Turdaş culture, Starčevo and Baden culture, which is characterised by West Balkan black and grey pottery. Bronze and Iron Age tombs have been found only in Rrafshi i Dukagjinit which is located in Kosovo.[3]

In classical antiquity, the area of Kosovo was part of Dardania. The name comes from the Dardani, a tribe that lived in the region and formed the Kingdom of Dardania in the 4th century BC. In archaeological research, Illyrian names are predominant in western Dardania (present-day Kosovo), while Thracian names are mostly found in eastern Dardania (present-day south-eastern Serbia). The eastern parts of the region were at the Thraco-Illyrian contact zone. Thracian names are absent in western Dardania; some Illyrian names appear in the eastern parts. The correspondence of Illyrian names – including those of the ruling elite – in Dardania with those of the southern Illyrians suggests a "thracianisation" of parts of Dardania.[7] The Dardani became one of the most powerful Illyrian states of their time under their king Bardylis.[8] Under the leadership of Bardylis, the Dardani defeated the Macedonians and Molossians several times, reigning over upper Macedonia and Lynkestis. Bardylis also led raids against Epirus.[8] Along with the Ardiaei and Autariatae, the Dardani are mentioned in Roman times by ancient Greek and Roman sources as one of the three strongest "Illyrian" peoples[9]

In addition, an ancient funeral inscription of the Albanoi was found near Skopje, corresponding to the ancient Dardania region.[10]

In 1854, Johann Georg von Hahn was the first to propose that the names Dardanoi and Dardania were related to the Albanian word dardhë ("pear, pear-tree"), stemming from Proto-Albanian *dardā, itself a derivative of derdh, "to tip out, pour", or *derda in Proto-Albanian.[11] A common Albanian toponym with the same root is Dardha, found in various parts of Albania, including Dardha in Berat, Dardha in Korça, Dardha in Librazhd, Dardha in Puka, Dardhas in Pogradec, Dardhaj in Mirdita, and Dardhës in Përmet. Dardha in Puka is recorded as Darda in a 1671 ecclesiastical report and on a 1688 map by a Venetian cartographer. Dardha is also the name of an Albanian tribe in the northern part of the District of Dibra.[12]

The region of Illyria was conquered by Rome in 168 BC, and made into the Roman province of Illyricum in 59 BC. The Kosovo region probably became part of Moesia Superior in AD 87, although archaeological evidence suggests that it may have been divided between Dalmatia and Moesia.[3]

.svg.png.webp)

After 284 Diocletian further divided Upper Moesia into the smaller provinces of Dardania, Moesia Prima, Dacia Ripensis, and Dacia Mediterranea. Dardania's capital was Naissus, previously a Celts settlement.[13] The Roman province of Dardania included eastern parts of modern Kosovo, while its western part belonged to the newly formed Roman province of Prevalitana with its capital Doclea. The Romans colonised the region and founded several cities.

The Hunnic invasions of 441 and 447–49 were the first barbarian invasions that were able to take Eastern Roman fortified centres and cities. Most Balkan cities were sacked by Attila, and recovered only partially if at all. While there is no direct written evidence of Hunnic invasion of Kosovo, its economic hinterland will anyway have been affected for centuries.[14] Justinian I, who assumed the throne of the Byzantine Empire in 527, oversaw a period of Byzantine expansion into former Roman territories, and re-absorbed the area of Kosovo into the empire.

Slavic migrations

Slavic migrations to the Balkans took place between the 6th to 7th centuries. The region had been part of the Roman and Byzantine empires until the first major Slav raids took place in the middle of Justinian's reign. In 547 and 548 the Slavs invaded the territory of modern Kosovo, and then got as far as Durrës on the Northern Albanian coast and reached all the way down to Greece.[15] The overwhelming number of municipalities in modern-day Kosovo being Slavic in their toponymy suggests that these Slavic raiders either assimilated, or expelled the local non-Slavic populations inhabiting the region of Kosovo prior to their arrival.[16] The plague of Justinian had killed millions of native Balkan people and as a result many regions had become depopulated and neglected by the government, this gave the Slavs a chance into settle in the Balkans.[17]

According to some historians, although some Slavs did spread out through these areas, there is one intriguing argument that suggests Slavic settlement in Kosovo and the Southern Morava Valley was weak in the first one or two centuries of Slavic settlement.[18] According to some historians and linguists, if Slavs had spread evenly in this part of the Balkans it would be hard to explain the clear linguistic division that occurred between the Bulgarian-Macedonian and Serbo-Croat language.[19] The scholar who first proposed this theory also noticed in the area that divided the early Serbs and the Bulgarians many Latin place-names in these areas survived long enough to be eventually adapted into Slavic ones, such as Naissus (Nis), Lypenion (Lipljan), Scupi (Skopje) etc.[20]

According to De Administrando Imperio, the ancestors of Serbs and Croats were part of the Slavic migrations into the Balkans, the Croats settled in modern Croatia and Western Bosnia whereas the Serbs in the rest of Bosnia, Travunija, Zahumlje and Duklja, lands situated North-West of Kosovo.

Middle Ages

According to historian Noel Malcolm the Vlach-Romanian and Aromanian languages originated in the region and surrounding areas from Romanised Illyrians and Thracians,[21][22] possibly a contact zone between the Albanian and Romanian language.[23][24][25]

.svg.png.webp)

The region of Kosovo was incorporated into the Bulgarian Empire during the reign of Khan Presian (836–852).[26] It remained within the borders of Bulgaria for 150 years until 1018, when it was retaken by the Byzantine Empire under Basil II (r. 976–1025) after half a century of campaigning. According to De Administrando Imperio of the 10th century Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII, the Serbian-populated lands lay to the north-west of Kosovo and the region was Bulgarian. One of the historical cities of Kosovo, Prizren is mentioned for the first time in 1019 in the form of Prisdriana. In 1072, the leaders of the Bulgarian Uprising of Georgi Voiteh traveled from their center in Skopje in the area of Prizren and held a meeting in which they invited Mihailo Vojislavljević of Duklja to send them assistance. Mihailo sent his son, Constantine Bodin with 300 of his soldiers. Dalassenos Doukas, dux of Bulgaria was sent against the combined forced but was defeated near Prizren, which was extensively plundered by the Serbian army after the battle.[27] The Bulgarian magnates proclaimed Bodin "Emperor of the Bulgarians" after this initial victory.[28] They were defeated by Nikephoros Bryennios in the area of northern Macedonia by the end of 1072. After the Byzantine Empire fully re-established itself, the region became part of the Byzantine Empire again and stayed under Byzantine rule until the 12th century.[29]

Stefan Nemanja had seized the surrounding area along the White Drin in 1185–95 and the ecclesiastical split from the Patriarchate in 1219 was the final act of establishing Nemanjić rule in Prizren and Kosovo. Prizren and its fort were the administrative and economic center of the župa of Podrimlje (in Albanian, Podrima or Anadrini). Demetrios Chomatenos is the last Byzantine archbishop of Ohrid to include Prizren in his jurisdiction until 1219.[30] Kosovo was fully annexed by Serbia during this period [31] and was part of the Serbian Empire (1346-1371). From the mid-13th century to the end of the century, the Nemanjić rulers had their main residences in Kosovo.[32] Large estates were given to the monasteries in Western Kosovo (Metohija). The most prominent churches in Kosovo – the Patriarchate of Peć at Peja, the church at Gračanica and the monastery at Visoki Dečani near Deçan – were all founded during this period. Kosovo was economically important and mining was an important industry in Novo Brdo and Janjevo which had its communities of émigré Saxon miners and Ragusan merchants. In 1450 the mines of Novo Brdo were producing about 6,000 kg of silver per year. The ethnic composition of Kosovo's population during this period included Serbs, Albanians, and Vlachs along with a token number of Greeks, Croats, Armenians, Saxons, and Bulgarians, according to Serbian monastic charters or chrysobulls.

.jpg.webp)

In 1355, the Serbian state fell apart on the death of Tsar Stefan Dušan and dissolved into squabbling fiefdoms. The timing fell perfectly within the Ottoman expansion. This enabled Albanian chieftains to create small principalities who had revolted several times with the aid of the Catholic Western powers. The First Battle of Kosovo occurred on the field of Kosovo Polje on June 28, 1389, when the ruling knez (prince) of Serbia, Lazar Hrebeljanović, marshalled a coalition of Christian soldiers led by Serbs that also included Bosnians, Albanians, Bulgarians, Magyars and a troop of Saxon mercenaries. Sultan Murad I also gathered a coalition of soldiers and volunteers from neighbouring countries in Anatolia and Rumelia. Although the battle has been mythologised as a great Christian defeat, at the time opinion was divided as to whether it was a Christian defeat, a stalemate or possibly even a Christian victory. Murad I was killed, according to tradition by Miloš Obilić, or Kobilić as he was always called until the 18th century. Serbian principalities continued their existence, usually as vassals of the Ottomans, and maintained sporadic control of Kosovo, until the final extinction of the Despotate of Serbia in 1459, following which Serbia became part of the Ottoman Empire. The fortress of Novo Brdo, important at the time due to its rich silver mines, came under siege for forty days by the Ottomans during that year, capitulating and becoming occupied by the Ottomans on June 1, 1455.[33] The Battle of Kosovo of 1389 had completely disorganised the Serb state, and left the field open to the most dynamic local lords, including among them the Albanian princes of the North and the Northeast. One of them was Gjon Kastrioti, the father of Skanderbeg, from the high region of Mati. At the end of the fourteenth and the start of the fifteenth century he managed to carve a principality from Ishmi to Prizren at the heart of region of Kosovo.[34] Part of western Kosovo was part of the Albanian principality of Dukagjini after which western Kosovo is known in Albanian as Dukagjin.[35]

Stefan Lazarević, Lazar's son, became a loyal ally of Bayezid, and contributed significant forces to many of Bayezid's future military engagements, including the Battle of Nicopolis, where Vuk Branković another Serbian magnate who ruled in parts of Kosovo had joined the anti-Ottoman coalition. As a reward for his contribution to the Ottoman victory, Lazarević was given a large part of Branković's lands, including the lands he held in Kosovo (1396-97). Branković himself died as an Ottoman prisoner, although in all later "Kosovo myth" narratives first created by Stefan Lazarević, he is portrayed as a betrayer of the Christians. The Second Battle of Kosovo was fought over two days in October 1448, between a Hungarian force led by John Hunyadi and an Ottoman army led by Murad II. John Hunyadi joined forces with Albania's Skanderbeg.[36][37] The Albanian army under Skanderbeg was delayed as it was prevented from linking with Hunyadi's army by the Ottomans and their allies. It is believed that the Albanian army was delayed by Serbian despot Đurađ Branković.[38] The Serbs had declined joining Hunyadi's forces following an earlier truce with the Turks.[39] As a result, Skanderbeg ravaged Brankovic's domains as punishment for the Serbian desertion of the Christian cause.[40] After Mehmed's death in 1421, Lazarević was one of the vassals who strongly supported the coalition against the future Mehmed the Conqueror who ultimately prevailed. This move led Mehmed to punish the Serbian and all other vassals who supported the other claimants to the throne by campaigning against them to directly annex their lands.[41]

Ottoman Period

_map.png.webp)

Western Kosovo had a significant reservoir of a native Albanian population by the time of the full Ottoman take over.[42][43][44][45] According to Malcolm, a major part of the Albanian demographic growth was the expansion of an indigenous Albanian population within Kosovo itself.[46]

While Serbian scholars may have come to the conclusion that the defter from 1455 indicates an overwhelmingly Serbian local population, other scholars have other views. Madgearu instead argues that the series of defters from 1455 onward "shows that Kosovo... was a mosaic of Serbian and Albanian villages", while Prishtina and Prizren already had significant Albanian Muslim populations.[47]

The Ottoman officials noted which heads of families were new arrivals in their places of residence; in the Sanjak of Prizren in 1591 only five new arrivals out of forty-one bore Albanian names. In the nahiye of Pec in 1485, the majority of new arrivals had Slavic names. In several Kosovo towns in the 1580s and 1590s; twenty five new Albanian immigrants were recorded and 133 immigrants with Slav names, several of them described coming from Bosnia.[48]

In 1557 the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć was re-established and many new Orthodox churches were built.[49] Orthodox Serbs gained the status of Millet, a religious community that enjoyed high levels of autonomy.[50] By the time the Patriarchate had been re-established in 1557 at Peja, the town of Peja may have gained a majority Muslim population.[51] The growth of Islam in early Ottoman Kosovo was mostly urban and from native people in the region converting to Islam.[52]

According to Frederick Anscombe, the town of Gjakova was Albanian since its founding in the late 1500s.[53] Antonio Bruni, writing in the late 1500s, stated that part of Dardania was inhabited by Albanians.[54] Lazaro Soranzo wrote of Albanians who lived as Catholics in the 1500s and noted that they inhabited the city of Prizren.[55] Catholic bishop Pjetër Mazreku noted in 1624 that the Catholics of Prizren were 200, the Serbs (Orthodox) 600, and Muslims, almost all of whom were Albanians, numbered 12,000.[56] In his 1662 work, Ottoman traveller Evliya Çelebi noted that the residents of Vushtrri were mostly Albanians.[57] Celebi described Western and parts of Central Kosovo as inhabited by Albanians.[58] According to sources from 17th century Kosovo, those in Western Kosovo spoke Albanian while those in Eastern Kosovo spoke Serbo-Croatian.[59]

Around the 17th century, there is a mention of some Catholic Albanians moving from the mountains of Northern Albania and into the plains of Kosovo. These families moved because they had fled blood feuds or they had been punished under the Kanun of Lek Dukagjin. However, the number of these people migrating into the area was, compared to the already existing Albanian population in Kosovo, extremely small.[60]

Albanian Catholic Gregor Mazrreku reported in the year 1651 that in Western Kosovo there had previously been many Catholics but converted to Islam in order to avoid taxes and impositions.[61][55] In Suha Reka where there had been previously 160 Catholic households, all the men had gone over to Islam.[61] Many Catholics in Kosovo also converted to Islam due to lack of priests, pressure from Ottoman authorities and the Orthodox church.[62] The Catholic church in Kosovo was poor and Catholics were pressured to pay taxes to the Orthodox Church.[62] According to Malcolm, compared to the Catholic church, the Serbian Orthodox church was larger, richer, more established and more privileged which led to less conversion to Islam.[63]

Kosovo in the Great Turkish War (1683-1699)

In 1689 during the Austrian-Ottoman wars, the Albanian Catholic Pjeter Bogdani organised a pro-Austrian movement and a resistance against the Ottomans in Kosovo together with the Albanian Catholic Toma Raspasani that included both Muslims and Christians.[64] An English embassy in Istanbul in 1690 reported of Austrians having made contact with 20,000 Albanians in Kosovo that had turned their weapons against the Turks.[55] A great deal of Albanians and Serbs alike joined the Austrians, while others fought on the side of the Ottomans. Ultimately the Austrians were driven back through the Danube, resulting in an influx of refugees and atrocities against the civilian population.[65] Toma Raspasani, writing in 1693 about the Catholics of Kosovo, observed that many of them had gone to Budapest where most of them died, some of hunger, others of disease.[66]

Aftermath

Serbian Patriarch Arsenije III Crnojević travelled to Belgrade which had been under Austrian rule and led 30,000 - 40,000 refugees to Hungary. According to Malcolm, most of the refugees that had gathered were from Niš and Belgrade area, along with a smaller number of Serb refugees from Eastern Kosovo that had managed to escape. This event is known as the Great Migrations of the Serbs. Malcolm believes that the historical evidence does not support a sudden mass exodus of Serbs out of Kosovo in 1690. If the Serb population was depleted in 1690, it looks as if it must have been replaced by inflows of Serbs from other areas.[67] Such flows did happen and from many different areas.[68] There was also a migration of Albanians from the Malsi but these were slow, long-term processes rather than involving sudden surges of population into a vacuum.[68]

Modern

During the period of Ottoman rule, several administrative districts known as sanjaks ("banners" or districts) each ruled by a sanjakbey (roughly equivalent to "district lord") have included parts of the territory. Despite the imposition of Muslim rule, large numbers of Christians continued to live and sometimes even prosper under the Ottomans. A process of Islamisation began shortly after the beginning of Ottoman rule but it took a considerable amount of time – at least a century – and was concentrated at first on the towns. A large part of the reason for the conversion was probably economic and social, as Muslims had considerably more rights and privileges than Christian subjects. Christian religious life nonetheless continued, while churches were largely left alone by the Ottomans, but both the Serbian Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches and their congregations suffered from high levels of taxation.

From the Establishment in 1757 until its dissolution following a War with the Ottomans in 1831, most of Kosovo was ruled by the Pashalik of Scutari and its Albanian dynasty under Kara Mahmud Pasha.[69][70] He conquered parts of Southern Albania and much of Kosovo.[71]

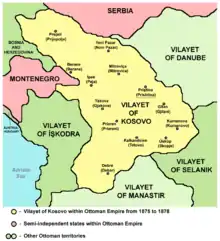

In 1877 the Vilayet of Kosovo was formed by the Ottoman administration. This was when Kosovo was used as the name of the entire territory for the first time,[72] a derivation from the Serbian word "Kos" (which means black bird).[73] It is shortened from Kosovo Polje meaning "Field of the Blackbirds",[74] where the Battle of Kosovo of 1389 was fought.

The vilayet was one of four with Albanian inhabitants that formed the League of Prizren. The League's purpose was to resist both Ottoman rule and incursions by the newly emerging Balkan nations.

In 1910, an Albanian insurrection, which was possibly aided surreptitiously by the Young Turks to put pressure on the Sublime Porte, broke out in Pristina and soon spread to the entire vilayet of Kosovo, lasting for three months. The Sultan visited Kosovo in June 1911 during peace settlement talks covering all Albanian-inhabited areas.

Albanian National Movement

The Albanian national movement was inspired by various factors. Besides the National Renaissance that had been promoted by Albanian activists, political reasons were a contributing factor. In the 1870s the Ottoman Empire experienced a tremendous contraction in territory and defeats in wars against the Slavic monarchies of Europe. During and after the Serbian–Ottoman War of 1876–78, between 30,000 and 70,000 Muslims, mostly Albanians, were expelled by the Serb army from the Sanjak of Niș and fled to the Kosovo Vilayet.[75][76][77][78][79][80] Furthermore, the signing of the Treaty of San Stefano marked the beginning of a difficult situation for the Albanian people in the Balkans, whose lands were to be ceded from Turkey to Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria.[81][82][83]

Fearing the partitioning of Albanian-inhabited lands among the newly founded Balkan kingdoms, the Albanians established their League of Prizren on June 10, 1878, three days prior to the Congress of Berlin that would revise the decisions of San Stefano.[84] Though the League was founded with the support of the Sultan who hoped for the preservation of Ottoman territories, the Albanian leaders were quick and effective enough to turn it into a national organisation and eventually into a government. The League had the backing of the Italo-Albanian community and had well developed into a unifying factor for the religiously diverse Albanian people. During its three years of existence the League sought the creation of an Albanian vilayet within the Ottoman Empire, raised an army and fought a defensive war. In 1881 a provisional government was formed to administer Albania under the presidency of Ymer Prizreni, assisted by prominent ministers such as Abdyl Frashëri and Sulejman Vokshi. Nevertheless, military intervention from the Balkan states, the Great Powers as well as Turkey divided the Albanian troops in three fronts, which brought about the end of the League.[84][85][86]

Kosovo was yet home to other Albanian organisations, the most important being the League of Peja, named after the city in which it was founded in 1899. It was led by Haxhi Zeka, a former member of the League of Prizren and shared a similar platform in quest for an autonomous Albanian vilayet. The League ended its activity in 1900 after an armed conflict with the Ottoman forces. Zeka was assassinated by a Serbian agent in 1902 with the backing of the Ottoman authorities.[87]

Balkan Wars

The demands of the Young Turks in early 20th century sparked support from the Albanians, who were hoping for a betterment of their national status, primarily recognition of their language for use in offices and education.[88][89] In 1908, 20,000 armed Albanian peasants gathered in Ferizaj to prevent any foreign intervention, while their leaders, Bajram Curri and Isa Boletini, sent a telegram to the sultan demanding the promulgation of a constitution and the opening of the parliament.

The Albanians did not receive any of the promised benefits from the Young Turkish victory. Considering this, an unsuccessful uprising was organised by Albanian highlanders in Kosovo in February 1909. The adversity escalated after the takeover of the Turkish government by an oligarchic group later that year. In April 1910, armies led by Idriz Seferi and Isa Boletini rebelled against the Turkish troops, but were finally forced to withdraw after having caused many casualties amongst the enemy.[90]

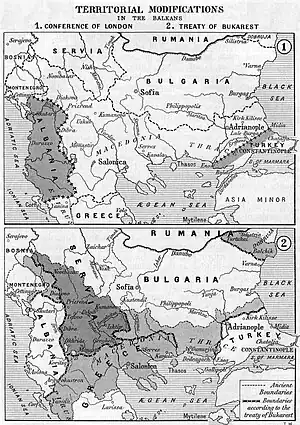

A further Albanian rebellion in 1912 was the pretext for Greece, Serbia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria beginning the First Balkan War against the Ottoman Empire. Most of Kosovo was incorporated into the Kingdom of Serbia, while the region of Metohija (Albanian: Dukagjini Valley) was taken by the Kingdom of Montenegro. Kosovo was split into four counties: three being a part of the entity of Serbia (Zvečan, Kosovo and southern Metohija); one of Montenegro (Northern Metohija).

The Albanian revolt of 1912 weakened the Ottoman Empire and resulted in an Albanian victory. This further persuaded other Balkan states that it was time for an anti-Ottoman war. The Ottomans had been so fatally weakened by the Albanian revolt of 1912 that the war was quickly won.[91][92]

Serbia took advantage of the Albanian rebellion after seeing a weakened Ottoman Empire and annexed Kosovo. The Albanians organised a resistance under the leadership of Isa Boletini. Serbia eventually managed to fight through and suppress the rebels. During the conflicts a number of massacres took place by the Serbian army and paramilitaries. Almost half of Albanian inhabited lands, including Kosovo, were left outside of what then formed as Albania and which were annexed by Montenegro and Serbia.[93]

During this period, the majority of the population of Kosovo was Albanian and did not welcome Serb rule.[94]

According to historian Noel Malcolm, the region was conquered, but not legally annexed, by Serbia in 1912 and remained occupied territory until 1918 when it became part of a Yugoslav kingdom.[94][95]

Many Albanians still kept resisting Serbian army and fought for the unification of Kosovo with Albania. Both Isa Boletini and Idriz Seferi continued fighting.[96] Other well known rebels at the time were Azem Galica, also known as Azem Bejta, and his wife Shote Galica.[97]

Interbellum Period

The 1918–1929 period of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians witnessed a rise of the Serbian population in the region and a decline in the non-Serbian. In 1929, Kosovo was split between the Zeta Banovina in the west with the capital in Cetinje, Vardar Banovina in the southeast with the capital in Skopje and the Morava Banovina in the northeast with the capital in Niš.[98]

Serbian troops attempted to alter the region's demographic structure through murders and mass expulsions. Between 1918 and 1945, over 100,000 Albanians left Kosovo[99][100]

Albanian schools and language were prohibited.[99] Tens of thousands of Serbs were settled in the region and land was confiscated from Albanian villagers.[99][100]

In 1938, more than 6000 people, in 23 villages, in the Drenica region of Kosovo were deprived of their land[101] The colonisation had put the Serb population at less than 24% in the start to 38%.[101] It was proposed to bring another 470,000 Serbs and expel 300,000 Albanians[101] but the outbreak of World War II prevented it from being put into effect.[101]

Second World War

After the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia in 1941, most of Kosovo was assigned to Italian-controlled Albania, with the rest being controlled by Germany and Bulgaria. A three-dimensional conflict ensued, involving inter-ethnic, ideological, and international affiliations, with the first being most important. Nonetheless, these conflicts were relatively low-level compared with other areas of Yugoslavia during the war years, with one Serb historian estimating that 3,000 Albanians and 4,000 Serbs and Montenegrins were killed, and two others estimating war dead at 12,000 Albanians and 10,000 Serbs and Montenegrins.[102] "We should endeavor to ensure that the Serb population of Kosovo should be removed as soon as possible ... All indigenous Serbs who have been living here for centuries should be termed colonialists and as such, via the Albanian and Italian governments, should be sent to concentration camps in Albania. Serbian settlers should be killed." Mustafa Kruja, the then Prime Minister of Albania, declared in June 1942.[103] The persecution of Serb and Montenegrin settlers by Albanian collaborationists resulted in thousands killed while between 70,000 and 100,000 were expelled or transferred to concentration camps in Pristina and Mitrovica.[104][105]

During the New Year's Eve between 1943 and 1944, Albanian and Yugoslav partisans gathered at the town of Bujan, near Kukës in northern Albania, where they held a conference in which they discussed the fate of Kosovo after the war. Both Albanian and Yugoslav communists signed the agreement, according to which Kosovo would have the right to democratically decide whether it wants to remain in Albania or become part of Serbia. This was seen as the Marxist solution for Kosovo. The agreement was not respected by Yugoslavia, since Tito knew that Serbia would not accept it.[106] Some Albanians, especially in the region in and around Drenica in central Kosovo revolted against the Yugoslav communists for not respecting the agreement. In response, the Yugoslavs called the rebels Nazi and Fascist collaborators and responded with violence. The Albanian Kosovar military leader Shaban Polluzha, who first fought with Yugoslav partisans but then refused to collaborate further, was attacked and killed.[107] Between 400 and 2,000 Kosovar Albanian recruits of the Yugoslav Army were shot in Bar.[108]

Yugoslavian Period

Following the end of the war and the establishment of Communist Yugoslavia, Kosovo was granted the status of an autonomous region of Serbia in 1946 and became an autonomous province in 1963. The Communist government did not permit the return of all of the refugees.

With the passing of the 1974 Yugoslavia constitution, Kosovo gained virtual self-government. The province's government has applied Albanian curriculum to Kosovo's schools: surplus and obsolete textbooks from Enver Hoxha's Albania were obtained and put into use.

Throughout the 1980s tensions between the Albanian and Serb communities in the province escalated.[109][110] The Albanian community favoured greater autonomy for Kosovo, whilst Serbs favoured closer ties with the rest of Serbia. There was little appetite for unification with Albania itself, which was ruled by a Stalinist government and had considerably worse living standards than Kosovo. Beginning in March 1981, Kosovar Albanian students organised protests seeking that Kosovo become a republic within Yugoslavia. Those protests rapidly escalated into violent riots "involving 20,000 people in six cities"[111] that were harshly contained by the Yugoslav government. The demonstrations of March and April 1981 were started by Albanian students[112] in Priština, protesting against poor living conditions and the lack of prospects (unemployment was rampant in the province and most of the university educated ended up as the unemployed). In addition, calls for a separate Albanian republic within Yugoslavia were voiced.

Serbs living in Kosovo were discriminated against by the provincial government, notably by the local law enforcement authorities failing to punish reported crimes against Serbs.[113] The increasingly bitter atmosphere in Kosovo meant that even the most farcical incidents could become causes célèbres. When a Serbian farmer, Đorđe Martinović, turned up at a Kosovo hospital with a bottle in his rectum after claiming to have been assaulted in his field by masked men (he later admitted the bottle ended up in his rectum through a mishap during masturbation),[114][115][116] 216 prominent Serbian intellectuals signed a petition declaring that "the case of Đorđe Martinović has come to symbolise the predicament of all Serbs in Kosovo."[117]

Perhaps the most politically explosive complaint levelled by the Kosovo Serbs was that they were being neglected by the Communist authorities in Belgrade.[118] In August 1987, Slobodan Milošević, then a rising politician, visited Kosovo. He appealed to Serb nationalism to further his career. Having drawn huge crowds to a rally commemorating the Battle of Kosovo, he pledged to Kosovo Serbs that "No one should dare to beat you", and became an instant hero of Kosovo's Serbs. By the end of the year Milošević was in control of the Serbian government.

In 1988 and 1989, dominant forces in Serbian politics engaged in a series of moves that became known as the anti-bureaucratic revolution. The leading politicians of Kosovo and the northern province of Vojvodina were sacked and replaced, and the level of autonomy of the provinces started to be unilaterally reduced by the Serbian federal authority. In protest, the Kosovo Albanians engaged in mass demonstrations, and Trepča miners began a hunger strike.

The new constitution significantly reduced the provinces' rights, permitting the government of Serbia to exert direct control over many previously autonomous areas of governance. In particular, the constitutional changes handed control of the police, the court system, the economy, the education system and language policies to the Serbian government.[119] It was strongly opposed by many of Serbia's national minorities, who saw it as a means of imposing ethnically based centralised rule on the provinces.[120]

The Albanian representatives in provincial government largely opposed the constitutional changes and abstained from ratification in the Kosovo assembly.[119] In March 1989, preceding a final push for ratification, the Yugoslav police rounded up around 240 prominent Kosovo Albanians, apparently selected based on their anti-ratification sentiment, and detained them with complete disregard for due process.[121] When the assembly met to discuss the proposals, tanks and armoured cars surrounded the meeting place.[122] Though the final vote failed to reach the required two-thirds majority threshold, it was declared as having passed.[119]

Kosovo War

| Part of a series on the |

| Kosovo War |

|---|

| Before March 1999 |

| NATO intervention |

| Other articles |

|

|

After the constitutional changes, the parliaments of all Yugoslavian republics and provinces, which until then had MPs only from the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, were dissolved and multi-party elections were held for them. Kosovo Albanians refused to participate in the elections and held their own, unsanctioned elections instead. As election laws required turnout higher than 50%, the parliament of Kosovo could not be established.

The new constitution abolished the individual provinces' official media, integrating them within the official media of Serbia while still retaining some programmes in Albanian. The Albanian-language media in Kosovo was suppressed. Funding was withdrawn from state-owned media, including that in Albanian in Kosovo. The constitution made creating privately owned media possible, however their functioning was very difficult because of high rents and restricting laws. State-owned Albanian-language television or radio was also banned from broadcasting from Kosovo.[123] However, privately owned Albanian media outlets appeared; of these, probably the most famous is "Koha Ditore", which was allowed to operate until late 1998 when it was closed after it published a calendar which was claimed to be a glorification of ethnic Albanian separatists.

The constitution also transferred control over state-owned companies to the Serbian government (at the time, most of the companies were state-owned). In September 1990, up to 12,000 Albanian workers were fired from their positions in government and the media, as were teachers, doctors, and workers in government-controlled industries,[124] provoking a general strike and mass unrest. Some of those who were not sacked quit in sympathy, refusing to work for the Serbian government. Although the sackings were widely seen as a purge of ethnic Albanians, the government maintained that it was simply getting rid of old communist directors.

The old Albanian educational curriculum and textbooks were revoked and new ones were created. The curriculum was basically the same as Serbian and that of all other nationalities in Serbia except that it had education on and in Albanian. Education in Albanian was withdrawn in 1992 and re-established in 1994.[125] At the Pristina University, which was seen as a centre of Kosovo Albanian cultural identity, education in Albanian was abolished and Albanian teachers were also sacked en masse. Albanians responded by boycotting state schools and setting up an unofficial parallel system of Albanian-language education.[126]

Kosovo Albanians were outraged by what they saw as an attack on their rights. Following mass rioting and unrest from Albanians as well as outbreaks of inter-communal violence, in February 1990, a state of emergency was declared, and the presence of the Yugoslav Army and police was significantly increased to quell the unrest.

Unsanctioned elections were held in 1992, which overwhelmingly elected Ibrahim Rugova as "president" of a self-declared Republic of Kosovo; however these elections were not recognised by Serbian nor any foreign government. In 1995, thousands of Serb refugees from Croatia settled in Kosovo, which further worsened relations between the two communities.

Albanian opposition to sovereignty of Yugoslavia and especially Serbia had surfaced in rioting (1968 and March 1981) in the capital Pristina. Ibrahim Rugova initially advocated non-violent resistance, but later opposition took the form of separatist agitation by opposition political groups and armed action from 1996 by the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA; Alb. Ushtria Çlirimtare e Kosovës or UÇK).

The KLA launched a guerrilla war and terror campaign, characterised by regular bomb and gun attacks on Yugoslav security forces, state officials and civilians known to openly support the national government, this included Albanians who were non-sympathisers with KLA motives. In March 1998, Yugoslav army units joined Serbian police to fight the separatists, using military force. In the months that followed, thousands of Albanian civilians were killed and more than 10,000 fled their homes; most of these people were Albanian. Many Albanian families were forced to flee their homes at gunpoint, as a result of fighting between national security and KLA forces leading to expulsions by the security forces including associated paramilitary militias. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimated that 460,000 people had been displaced from March 1998 to the start of the NATO bombing campaign in March 1999.[127]

There was violence against non-Albanians as well: UNHCR reported (March 1999) that over 90 mixed villages in Kosovo "have now been emptied of Serb inhabitants" and other Serbs continue leaving, either to be displaced in other parts of Kosovo or fleeing into central Serbia. The Yugoslav Red Cross estimated there were more than 130,000 non-Albanian displaced in need of assistance in Kosovo, most of whom were Serb.[128]

Following the breakdown of negotiations between Serbian and Albanian representatives, under North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) auspices, NATO intervened on March 24, 1999, without United Nations authority. NATO launched a campaign of heavy bombing against Yugoslav military targets and then moved to wide range bombings (like bridges in Novi Sad). A full-scale war broke out as KLA continued to attack Serbian forces and Serbian/Yugoslav forces continued to fight KLA amidst a massive displacement of the population of Kosovo, which most human rights groups and international organisations regarded as an act of ethnic cleansing perpetrated by the government forces. A number of senior Yugoslav government officials and military officers, including President Milošević, were subsequently indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) for war crimes. Milošević died in detention before a verdict was rendered.[129]

The United Nations estimated that during the Kosovo War, nearly 40,000 Albanians fled or were expelled from Kosovo between March 1998 and the end of April 1999. Most of the refugees went to Albania, the Republic of Macedonia, or Montenegro. Government security forces confiscated and destroyed the documents and licence plates of many fleeing Albanians in what was widely regarded as an attempt to erase the identities of the refugees, the term "identity cleansing" being coined to denote this action. This made it difficult to distinguish with certainty the identity of returning refugees after the war. Serbian sources claim that many Albanians from Macedonia and Albania – perhaps as many as 300,000, by some estimates – have since migrated to Kosovo in the guise of refugees.

Independence

The war ended on June 10, 1999, with the Serbian and Yugoslav governments signing the Kumanovo Agreement which agreed to transfer governance of the province to the United Nations. A NATO-led Kosovo Force (KFOR) entered the province following the Kosovo War, tasked with providing security to the UN Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK). In the weeks after, as many as 164,000 non-Albanians, primarily Serbs but also Roma, fled the province for fear of reprisals, and many of the remaining civilians were victims of abuse.[130] The Roma in particular were regarded by many Albanians as having assisted the Serbs during the war. Thousands more were driven out by intimidation, attacks and a wave of crime after the war as KFOR struggled to restore order in the province.[130]

Large numbers of refugees from Kosovo still live in temporary camps and shelters in Serbia proper. In 2002, Serbia and Montenegro reported hosting 277,000 internally displaced people (the vast majority being Serbs and Roma from Kosovo), which included 201,641 persons displaced from Kosovo into Serbia proper, 29,451 displaced from Kosovo into Montenegro, and about 46,000 displaced within Kosovo itself, including 16,000 returning refugees unable to inhabit their original homes.[131][132] Some sources put the figure far lower; the European Stability Initiative estimates the number of displaced people as being only 65,000, with another 40,000 Serbs remaining in Kosovo, though this would leave a significant proportion of the pre-1999 ethnic Serb population unaccounted-for. The largest concentration of ethnic Serbs in Kosovo is in the north of the province above the Ibar river, but an estimated two-thirds of the Serbian population in Kosovo continues to live in the Albanian-dominated south of the province.[133]

Right: 14th-century icon from UNESCO World Heritage Site Our Lady of Ljeviš in Prizren damaged during 2004 unrest.

On March 17 and 18, 2004, unrest in Kosovo led to 19 deaths (11 Kosovo Albanians and 8 Kosovo Serbs), the burning of at least 550 homes and the destruction of 27-35 Serbian Orthodox churches and monasteries in the province after Albanian rioting targeted Serbs.[134] Several thousand more Kosovo Serbs have left their homes to seek refuge in Serbia proper or in the Serb-dominated north of Kosovo.

Since the end of the war, Kosovo has been a major source and destination country in the trafficking of women, women forced into prostitution and sexual slavery. The growth in the sex trade industry has been fuelled by NATO forces in Kosovo.[135][136][137]

International negotiations began in 2006 to determine the final status of Kosovo, as envisaged under UN Security Council Resolution 1244 which ended the Kosovo conflict of 1999. Whilst Serbia's continued sovereignty over Kosovo was recognised by the international community, a clear majority of the province's population sought independence.

The United Nations-backed talks, led by UN Special Envoy Martti Ahtisaari, began in February 2006. Whilst progress was made on technical matters, both parties remained diametrically opposed on the question of status itself.[138] In February 2007, Ahtisaari delivered a draft status settlement proposal to leaders in Belgrade and Pristina, the basis for a draft UN Security Council Resolution which proposes 'supervised independence' for the province. As of early July 2007 the draft resolution, which is backed by the United States, United Kingdom and other European members of the Security Council, had been rewritten four times to try to accommodate Russian concerns that such a resolution would undermine the principle of state sovereignty.[139] Russia, which holds a veto in the Security Council as one of five permanent members, has stated that it will not support any resolution which is not acceptable to both Belgrade and Pristina.[140]

On 17 February 2008 Kosovo unilaterally declared its independence,[1] and subsequently adopted the Constitution of Republic of Kosovo, which came into effect on 15 June 2008.[141] Some Kosovo Serbs opposed to secession boycotted the move by refusing to follow orders from the central government in Pristina and attempted to seize infrastructure and border posts in Serb-populated regions. There have also been sporadic instances of violence against international institutions and governmental institutions, predominantly in Northern Kosovo (see 2008 unrest in Kosovo).

On July 25, 2011, Kosovan Albanian police wearing riot gear attempted to seize several border control posts in Kosovo's Serb-controlled north trying to enforce the ban on Serbian imports imposed in retaliation of Serbia's ban on import from Kosovo. It prompted a large crowd to erect roadblocks and Kosovan police units came under fire. An Albanian policeman died when his unit was ambushed and another officer was reportedly injured. Nato-led peacekeepers moved into the area to calm the situation and Kosovan police pulled back. The US and EU criticised the Kosovan government for acting without consulting international bodies.[142][143]

Some rapprochement between the two governments took place on 19 April 2013 as both parties reached the Brussels Agreement, an agreement brokered by the EU that allowed the Serb minority in Kosovo to have its own police force and court of appeals.[144] The accord was ratified by the Kosovo assembly on 28 June 2013.[145][146]

In April 2021, Kosovo parliament elected Vjosa Osmani as new president for a five-year term. She was Kosovo's seventh president, and the second female president, in the post-war period. Osmani had the backing of the left-wing Self-Determination Movement (Vetevendosje) of Prime Minister Albin Kurti, which won the February 2021 parliamentary election.[147]

In September 2021, Serbs from Kosovo's north had blocked two main roads, protesting a ban on cars with Serbian licence plates entering Kosovo without temporary printed registration details. Two interior ministry buildings in northern Kosovo, including a car registration office, were attacked. Serbia began military manoeuvres near the border and started flying military jets above the border crossing. Kosovo's NATO mission stepped up patrols near border crossings.[148] On September 30, 2021, an agreement between Kosovo and Serbia was reached to end the stand-off. Kosovo agreed to withdraw police special forces.[149] In late July 2022 tensions flared up again when the Kosovo government declared that Serb-issued identity documents and vehicle licence plates would be invalid, prompting Serbs in North Kosovo to protest by blocking roads. The decision on the part of Kosovo authorities was seen as a reciprocal move given that Kosovo documents are rejected in Serbia. In August, EU-mediated talks resulted in an agreement between Serbia and Kosovo whereby Serbia would abolish special document requirements for Kosovo ID holders and Kosovo would not introduce them for Serbian ID holders.[150] In November, ethnic Serbs resigned en masse from Kosovo state institutions in protest and tensions continued through the end of the year.[151]

See also

References

- "ACCORDANCE WITH INTERNATIONAL LAW OF THE UNILATERAL DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE IN RESPECT OF KOSOVO" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-08-21. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- Ajdini, Sh.; Bytyqi, Q.; Bycinca, H.; Dema, I.; et al. (1975), Ferizaj dhe rrethina, Beograd, pp. 43–45

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Djordje Janković: Middle Ages in Noel Malcolm's "Kosovo. A Short History" and Real Facts Archived 2015-02-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Milot Berisha, Archaeological Guide of Kosovo, Prishtinë, Kosovo Archaeological Institute and Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports, 2012, p. 7.

- Milot Berisha, Archaeological Guide of Kosovo, Prishtinë, Kosovo Archaeological Institute and Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports, 2012, p. 8.

- Porčić et al. 2020, p. 6.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 85

Whether the Dardanians were an Illyrian or a Thracian people has been much debated and one view suggests that the area was originally populated with Thracians who then exposed to direct contact with Illyrians over a long period. [..] The meaning of this state of affairs has been variously interpreted, ranging from notions of Thracianization' (in part) of an existing Illyrian population to the precise opposite. In favour of the latter may be the close correspondence of Illyrian names in Dardania with those of the southern 'real' lllyrians to their west, including the names of Dardanian rulers, Longarus, Bato, Monunius and Etuta, and those on later epitaphs, Epicadus, Scerviaedus, Tuta, Times and Cinna.

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1967). Epirus: the Geography, the Ancient Remains, the History and Topography of Epirus and Adjacent Areas. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198142536.

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1966). "The Kingdoms in Illyria circa 400-167 B.C.". The Annual of the British School at Athens. British School at Athens. 61: 239–253. JSTOR 30103175.

- Dragojević-Josifovska 1982, p. 32.

- Orel, Vladimir E. (1998). Albanian Etymological Dictionary. Brill. p. 56. ISBN 978-90-04-11024-3.

- Elsie, Robert (2015). The Tribes of Albania: History, Society and Culture. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857739322.

- "Nis | History, Facts, & Points of Interest". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire, 2005, pp. 325–350.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 23.

- Kingsley, Thomas (2022). "Albanian Onomastics - Using Toponymic Correspondences to Understand the History of Albanian Settlement". 6th Annual Linguistics Conference at the University of Georgia: 117. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- "The plague pandemic and Slavic expansion in the 6th–8th centuries". ResearchGate.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 26.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 27.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 26-27.

- Kosovo: A Short History, Origins: Serbs, Albanians and Vlachs. "The main area of the Balkan interior where a Latin-speaking population may have continued, in both towns and country, after the Slav invasion, has already been mentioned: it included the upper Morava valley, northern Macedonia, and the whole of Kosovo. It is, therefore, in the uplands of the Kosovo area (particularly, but not only, on the western side, including parts of Montenegro) that this Albanian-Vlach symbiosis probably developed. All the evidence comes together at this point. What it suggests is that the Kosovo region, together with at least part of northern Albania, was the crucial focus of two distinct but interlinked ethnic histories: the survival of the Albanians, and the emergence of the Romanians and Vlachs. One large group of Vlachs seems to have broken away and moved southwards by the ninth or tenth century; the proto-Romanians stayed in contact with Albanians significantly longer, before drifting north-eastwards, and crossing the Danube in the twelfth century."

- Kosovo: A Short History, Origins: Serbs, Albanians and Vlachs. "Only the remnants of a Latin-speaking population survived in parts of the central and west-central Balkans; when it re-emerges into the historical record in the tenth and eleventh centuries, we find its members leading a semi-nomadic life as shepherds, horse-breeders and travelling muleteers. These were the Vlachs, who can still be seen tending their flocks in the mountains of northern Greece, Macedonia and Albania today. [14] The name 'Vlach' was a word used by the Slavs for those they encountered who spoke a strange, usually Latinate, language; the Vlachs' own name for themselves is 'Aromanians' (Aromani). As this name suggests, the Vlachs are closely linked to the Romanians: their two languages (which, with a little practice, are mutually intelligible) diverged only in the ninth or tenth century. While Romanian historians have tried to argue that the Romanian-speakers have always lived in the territory of Romania (originating, it is claimed, from Romanised Dacian tribes and/or Roman legionaries), there is compelling evidence to show that the Romanian-speakers were originally part of the same population as the Vlachs, whose language and way of life were developed somewhere to the south of the Danube. Only in the twelfth century did the early Romanian-speakers move northwards into Romanian territory."

- Kosovo: A Short History, Origins, Serbs, Albanians and Vlachs.

- The Early History of the Rumanian Language, Andre Du Nay.

- Endre Haraszti; (1977) Origin of the Rumanians (Vlach Origin, Migration and Infiltration to Transylvania) p. 60-61; Danubian Press.

- Elsie 2010, p. 54.

- Stojkovski 2020, p. 147.

- McGeer 2019, p. 149.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 28.

- Prinzing 2008, p. 30.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 44.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 50.

- Malcolm 1998, pp. 81–92.

- Lellio, Anna Di (July 10, 2006). The Case for Kosova: Passage to Independence. Anthem Press. ISBN 9781843312451 – via Google Books.

- Sellers, Mortimer; Tomaszewski, Tadeusz (July 23, 2010). The Rule of Law in Comparative Perspective. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9789048137497 – via Google Books.

- Turnbull 2012, p. 35.

- Phillips & Axelrod 2005, p. 20.

- Sedlar 2013, p. 393.

- Sedlar 2013, p. 248.

- Kenneth, Setton (1997) [1978]. The papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571: The thirteenth and fourteenth centuries p. 100.

- Djokić 2023, p. 131.

- Malcolm 1998, pp. 111–114.

- A.Hanzic – Nekoliko vijesti o Arbanasima na Kosovu I Metohiji v sredinom XV vijeka pp.201–9.

- Milan Sufflay: Povijest Sjevernih Arbanasa pp. 61–2.

- Selami Pulaha – Defteri I Regjistrimit te Sanxhakut te Shkodres I vitit 1485.

- Malcolm 1998, pp. 36, 111–112.

- Madgearu, Alexandru; Gordon, Martin (2008). The Wars of the Balkan Peninsula: Their Medieval Origins. Scarecrow Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8108-5846-6.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 112.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 109.

- Myths of Kosovo: The History of Kosovo Through the Eyes of Dusan T. Batakovic - Melle Havermans p. 30.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 111.

- Malcolm 1998, pp. 105–106.

- Frederick F Anscombe p. 785.

- Malcolm 2020, p. 46.

- Malcolm 2020.

- Malcolm 2020, p. 136.

- Çelebi, Evliya (2000). Dankoff, Robert; Kreiser, Klaus; Elsie, Robert (eds.). Evliya Çelebi in Albania and Adjacent Regions: Kossovo, Montenegro, Ohrid. BRILL. p. 17. ISBN 978-9-0041-1624-5.

- Anscombe, Frederic F, (2006). "The Ottoman Empire in Recent International Politics – II: The Case of Kosovo". The International History Review. 28.(4): 767–774, 785–788.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 137.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 138.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 131.

- Malcolm 1998, pp. 126–127.

- Malcolm 1998, pp. 127–128.

- Malcolm 2020, pp. 134–136.

- Lawson, Kenneth E. (2006). Faith and hope in a war-torn land. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 111. ISBN 9780160872792.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 162.

- Malcolm 2020, pp. 128–129, 143.

- Malcolm 2020, p. 143.

- Vickers, Miranda (1999). The Albanians: A Modern History. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-86064-541-9.

- Iseni, Bashkim (2008). La question nationale en Europe du Sud-Est: genèse, émergence et développement de l'indentité nationale albanaise au Kosovo et en Macédoine (in French). Peter Lang. p. 120. ISBN 978-3-03911-320-0.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 176.

- Fábián & Trost 2019, p. 349.

- Judah 2008, p. 31.

- Everett-Heath, John (2018). The Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names (Fourth ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 767. ISBN 978-0-19256-243-2.

- Pllana, Emin (1985). "Les raisons de la manière de l'exode des refugies albanais du territoire du sandjak de Nish a Kosove (1878–1878) [The reasons for the manner of the exodus of Albanian refugees from the territory of the Sanjak of Niš to Kosovo (1878–1878)] ". Studia Albanica. 1: 189–190.

- Rizaj, Skënder (1981). "Nënte Dokumente angleze mbi Lidhjen Shqiptare të Prizrenit (1878–1880) [Nine English documents about the League of Prizren (1878–1880)]". Gjurmine Albanologjike (Seria e Shkencave Historike). 10: 198.

- Şimşir, Bilal N, (1968). Rumeli’den Türk göçleri. Emigrations turques des Balkans [Turkish emigrations from the Balkans]. Vol I. Belgeler-Documents. p. 737.

- Bataković, Dušan (1992). The Kosovo Chronicles. Plato.

- Elsie 2010, p. XXXII.

- Stefanović, Djordje (2005). "Seeing the Albanians through Serbian eyes: The Inventors of the Tradition of Intolerance and their Critics, 1804–1939." European History Quarterly. 35. (3): 470.

- Hysni Myzyri, "Kriza lindore e viteve 70 dhe rreziku i copëtimit të tokave shqiptare," Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 151.

- "LIDHJA SHQIPTARE E PRIZRENIT – (1878–1881)". historia.shqiperia.com.

- "UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo – 11. Prizren Municipality". www.hrw.org.

- Г. Л. Арш, И. Г. Сенкевич, Н. Д. Смирнова «Кратая история Албании» (Приштина: Рилиндя, 1967) 104–116.

- Hysni Myzyri, "Kreu VIII: Lidhja Shqiptare e Prizrenit (1878–1881)," Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 149–172.

- "LIDHJA SHQIPTARE E PRIZRENIT – (1878–1881)". historia.shqiperia.com.

- Hysni Myzyri, "Kreu VIII: Lidhja Shqiptare e Prizrenit (1878–1881)," Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 182–185.

- Hysni Myzyri, "Lëvizja kombëtare shqiptare dhe turqit e rinj," Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 191.

- Г. Л. Арш, И. Г. Сенкевич, Н. Д. Смирнова «Кратая история Албании» (Приштина: Рилиндя, 1967) 140–160.

- Hysni Myzyri, "Kryengritjet shqiptare të viteve 1909–1911," Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 195–198.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 248.

- Anna Di Lellio - The Case for Kosova, p. 55.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 251.

- Malcolm, Noel (February 26, 2008). "Noel Malcolm: Is Kosovo Serbia? We ask a historian". the Guardian.

- Malcolm, Noel (December 1998). "Kosovo: Only Independence Will Work". The National Interest.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 252.

- Elsie 2010, p. XXXVI, 107.

- Mylonas, H. (2013). The Politics of Nation-Building: Making Co-Nationals, Refugees, and Minorities. Problems of International Politics. Cambridge University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-139-61981-3.

- . Political parties of Eastern Europe: a guide to politics in the post-Communist era p. 448-449.

- Anna Di Lellio The Case for Kosova p. 61.

- Anna Di Lellio - The Case for Kosova, p. 61.

- Malcolm 1998, p. 312.

- Pinos, J.C. (2018). Kosovo and the Collateral Effects of Humanitarian Intervention. Routledge Borderlands Studies. Taylor & Francis. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-351-37476-7.

- Bieber, Florian; Daskalovski, Zidas (2004). Understanding the War in Kosovo. Routledge. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-13576-155-4.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918-2005. Indiana University Press. pp. 114, 141. ISBN 978-0-25334-656-8.

- "The Resolution of Bujan". Albanian History. Robert Elsie. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- Elsie, R. (2004). Historical Dictionary of Kosova. European historical dictionaries. Scarecrow Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-8108-5309-6.

- Fevziu, B.; Elsie, R.; Nishku, M. (2016). Enver Hoxha: The Iron Fist of Albania. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-85772-703-9.

- Reuters 1986-05-27, "Kosovo Province Revives Yugoslavia's Ethnic Nightmare"

- Christian Science Monitor 1986-07-28, "Tensions among ethnic groups in Yugoslavia begin to boil over"

- New York Times 1981-04-19, "One Storm has Passed but Others are Gathering in Yugoslavia"

- "Die Zukunft des Kosovo". Bits.de. Retrieved 2012-11-09.

- New York Times 1982-07-12, "Exodus of Serbians Stirs Province in Yugoslavia"

- Sabrina P. Ramet, Angelo Georgakis. Thinking about Yugoslavia: Scholarly Debates about the Yugoslav Breakup and the Wars in Bosnia and Kosovo, pp. 153, 201. Cambridge University Press, 2005; ISBN 1-397-80521-8

- Sell, Louis (2003). Slobodan Milosevic and the Destruction of Yugoslavia. Durham. pp. 78–79. ISBN 0-8223-3223-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Zgodovina – Inštitut za sodno medicino". Ism-mf.si. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- Mertus, Julie (1999). Kosovo: How Myths and Truths Started a War. University of California Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-5202-1865-9.

- New York Times 1987-06-27, "Belgrade Battles Kosovo Serbs"

- Krieger 2001, p. 522.

- Yugoslavia The Old Demons Arise, Time Magazine, August 06, 1990.

- Anderson 1990, pp. 27–29.

- Judah 2008, p. 56.

- "Helsinki". www.hrw.org. Archived from the original on October 27, 2004.

- Wolfgang Plarre. "ON THE RECORD: //Civil Society in Kosovo// – Volume 9, Issue 1 – August 30, 1999 – THE BIRTH AND REBIRTH OF CIVIL SOCIETY IN KOSOVO – PART ONE: REPRESSION AND RESISTANCE". Bndlg.de. Retrieved 2012-11-09.

- Archived October 10, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- Clark, Howard. Civil Resistance in Kosovo. London: Pluto Press, 2000. ISBN 0-7453-1569-0

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Kosovo Crisis Update". UNHCR. Retrieved 2012-11-09.

- Archived December 10, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- Seth, Michael J. (2021). Not on the Map: The Peculiar Histories of De Facto States. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-7936-3253-1.

- "Abuses against Serbs and Roma in the new Kosovo". hrw.org. Human Rights Watch. August 1999.

- Archived October 29, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- Archived June 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "Chronology of all ESI publications – Reports – ESI". Esiweb.org. Retrieved 2012-11-09.

- "Failure to Protect: Anti-Minority Violence in Kosovo, March 2004". hrw.org. Human Rights Watch. July 2004.

- "Amnesty International | Working to Protect Human Rights". Web.amnesty.org. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2012-11-09.

- Ian Traynor in Zagreb (2004-05-07). "Nato force 'feeds Kosovo sex trade' | World news". The Guardian. Retrieved 2012-11-09.

- "Conflict, Sexual Trafficking, and Peacekeeping". Archived from the original on November 21, 2006. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- "UN frustrated by Kosovo deadlock ", BBC News, October 9, 2006.

- "Russia reportedly rejects fourth draft resolution on Kosovo status". SETimes.com. 2007-06-29. Retrieved 2012-11-09.

- "UN Security Council remains divided on Kosovo". SETimes.com. 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2012-11-09.

- Bilefsky, Dan (15 June 2008). "Tension mounts as Kosovo Constitution takes effect". The New York Times.

- "Nato Steps In Amid Kosovo-Serbia Border Row".

- "Kosovo tense after border clash". BBC News. 27 July 2011.

- "Serbia and Kosovo reach EU-brokered landmark accord". BBC News. 2013-04-19. Retrieved 2022-08-02.

- "LIGJI NR. 04/L-199 PËR RATIFIKIMIN E MARRËVESHJES SË PARË NDËRKOMBËTARE TË PARIMEVE QË RREGULLOJNË NORMALIZIMIN E MARRËDHËNIEVE MES REPUBLIKËS SË KOSOVËS DHE REPUBLIKËS SË SERBISË". 2020-10-24. Archived from the original on 2020-10-24. Retrieved 2022-08-02.

- "Kosovo MPs Defy Protests to Ratify Serbia Deal". Balkan Insight. 2013-06-28. Retrieved 2022-08-02.

- "Kosovo parliament elects Vjosa Osmani as new president". www.aljazeera.com.

- "NATO increases patrols near Kosovo-Serbia border blockage". CNN. 28 September 2021.

- "Kosovo, Serbia Agree to End Border Blockade Without Solution to Licence Plate Dispute". BalkanInsight. 30 September 2021.

- "EU official says Serbia, Kosovo agree on IDs in step forward". ABC News. The Associated Press. 27 August 2022.

- Bahri, Cani; Rujevic, Nemanja (27 December 2022). "What's behind the tensions between Kosovo and ethnic Serbs?". Deutsche Welle.

Sources

- Baker, Catherine. "Between the round table and the waiting room: Scholarship on war and peace in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo after the ‘Post-Cold War’." Contemporary European History 28.1 (2019): 107–119. online

- Anderson, Kenneth (1990). Yugoslavia, Crisis in Kosovo: A Report from Helsinki Watch and the International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights. Human Rights Watch. ISBN 9780929692562.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Ćurčić, Slobodan (1979). Gračanica: King Milutin's Church and Its Place in Late Byzantine Architecture. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 9780271002187.

- Djokić, Dejan (2023). A Concise History of Serbia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139236140.

- Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical Dictionary of Kosovo (Illustrated ed.). Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810874831.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472082604.

- Gavrilović, Zaga (2001). Studies in Byzantine and Serbian Medieval Art. London: The Pindar Press. ISBN 9781899828340.

- Judah, Tim (29 September 2008). Kosovo: what everyone needs to know. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195376739. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- Krieger, Heike (2001). The Kosovo Conflict and International Law: An Analytical Documentation 1974–1999. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521800716.

- Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: A Short History. Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-66612-7.

- Malcolm, Noel (2020). Rebels, Believers, Survivors: Studies in the History of the Albanians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19259-922-3.

- McGeer, Eric (2019). Byzantium in the Time of Troubles: The Continuation of the Chronicle of John Skylitzes (1057–1079). BRILL. ISBN 978-9004419407.

- Mojzes, Paul (2011). Balkan Genocides: Holocaust and Ethnic Cleansing in the 20th Century. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. ISBN 9781442206632. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- Pejin, Jovan (2006). "The Extermination of the Serbs in Metohia, 1941–1944" (PDF). Срби на Косову и у Метохији: Зборник радова са научног скупа. Београд: Српска академија наука и уметности. pp. 189–207.

- Porčić, Marko; Blagojević, Tamara; Pendić, Jugoslav; Stefanović, Sofija (2020). "The timing and tempo of the Neolithic expansion across the Central Balkans in the light of the new radiocarbon evidence". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 33: 102528. Bibcode:2020JArSR..33j2528P. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2020.102528.

- Prinzing, Günter (2008). "Demetrios Chomatenos, Zu seinem Leben und Wirken". Demetrii Chomateni Ponemata diaphora: [Das Aktencorpus des Ohrider Erzbischofs Demetrios. Einleitung, kritischer Text und Indices]. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110204506.

- Soulis, George Christos (1984). The Serbs and Byzantium during the reign of Tsar Stephen Dušan (1331–1355) and his successors. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Library and Collection. ISBN 9780884021377.

- Stojkovski, Boris (2020). "Byzantine military campaigns against Serbian lands and Hungary in the second half of the eleventh century.". In Theotokis, Georgios; Meško, Marek (eds.). War in Eleventh-Century Byzantium. Routledge. ISBN 978-0429574771.

- Wilkes, J. J. (1992). The Illyrians. Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-19807-5.

External links

Media related to History of Kosovo at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to History of Kosovo at Wikimedia Commons- Under Orders: War Crimes in Kosovo – Human Rights Watch (Online book)

- Report of the International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan War (1914)

- Richard Jansen: Albanians and Serbs in Kosovo: An Abbreviated History

- Tim Judah: Kosovo History, bloody history

- Dušan T. Bataković: The Kosovo Chronicles

- Serbian Orthodox Church: History of Kosovo, articles, studies

- Bloody Struggles from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

_-_Kosovo.jpg.webp)