Finland under Swedish rule

In Swedish and Finnish history, Finland under Swedish rule is the historical period when the bulk of the area that later came to constitute Finland was an integral part of Sweden. The starting point of Swedish rule is uncertain and controversial. Historical evidence of the establishment of Swedish rule in Finland exists from the late 13th century onwards.

| Finland | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Sweden | |||||||||

| 1150s–1809 | |||||||||

Map of Sweden (1747) | |||||||||

| Capital | Stockholm | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| Government | |||||||||

| • Type | Lands of Sweden | ||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||

• 1250–1275 | Valdemar | ||||||||

• 1792–1809 | Gustav IV Adolf (Last) | ||||||||

| Regent | |||||||||

• 1438–1440 | Karl Knutsson Bonde | ||||||||

• 1512–1520 | Sten Sture the Younger | ||||||||

| Legislature | Riksdag of the Estates | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages to Napoleonic Wars | ||||||||

| 1150s | |||||||||

• Established | 1150s | ||||||||

| 1397–1523 | |||||||||

| 1611–1721 | |||||||||

| 1808–1809 | |||||||||

| 1809 | |||||||||

| 17 September 1809 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Finland | ||||||||

Swedish rule ended in most of so-called Old Finland, the south-eastern part of the Finnish territories, in 1721 as a result of the Great Northern War. Sweden ceded the remainder of Old Finland in 1743 following the Hats' War. On 17 September 1809, the period of Swedish rule over the rest of Finland came to an end when the Treaty of Hamina was signed, ending the Finnish War. As a result, the eastern third of Sweden was ceded to the Russian Empire and became established as the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland.

Swedish rule in the area of modern-day Finland started as a result of the Northern Crusades. The Finnish upper class lost its position and lands to new Swedish and German nobility and to the Catholic Church.[1] The Swedish colonisation of some coastal areas of Finland with Christian population was a way to retain power in former pagan areas that had been conquered. It has been estimated that there were thousands of colonists.[2] Colonisation led to several conflicts between the colonists and local population which have been recorded in the 14th century. In colonised areas the Finnish population principally lost its fishing and cultivation rights to the colonists.[3][4] Though the Finnish provinces were an integral part of the Kingdom of Sweden with the same legal rights and duties as the rest of the realm, Finnish-speaking Swedish subjects faced comparative challenges in dealing with the authorities as Swedish was established as the sole official language of government. In fact, it remained a widely accepted view in Sweden proper that the Finns were in principle a separate and conquered people and therefore not necessarily entitled to be treated equitably with Swedes. Swedish kings visited Finland rarely and in Swedish contemporary texts Finns were often portrayed as primitive and their language inferior.[5] Approximately half of the taxes collected in Finland was used in the country, while the other half was transferred to Stockholm.[6]

Under Sweden, Finland was annexed as part of the Western Christian domain and the cultural, communal and economic order of Western Europe, on which the market economy, constitutional governments and legalistic principles were founded. Finland was the eastern frontier of the realm, which brought many wars and raids to the areas. The Finnish language, dating from prehistoric times, and some parts of folklore religion and culture remained under Swedish rule, even though they changed as they adapted to new circumstances.[7] For example, in this period Finnish adopted the Latin alphabet as its writing system and approximately 1100 Swedish loanwords, though most of them are originally from Latin or Greek.[8]

Swedish-ruled Finland has in the 20th century also been referred to as "Sweden–Finland". The term has been used to refer to the realm consisting of the main parts of current Sweden and Finland. The historian Peter Englund has noted that Swedish-ruled Finland was not so much part of a national union or a province as "the eastern half of the realm which was practically destroyed in 1809, when both parts went on along their separate ways." Englund thinks that the period of Sweden as a superpower was the common "property" of Sweden and Finland, because the rise as a superpower would have been impossible for a poor nation without the resources of the eastern part of the realm.[9]

For a time, Finns were considered by a majority of historians to be the first inhabitants of Sweden together with the Sámi. This was also believed by some Swedish historians, like Olof von Dalin (18th century), who believed them to be one of the biblical Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. This change in attitude largely stemmed from a need to create a more equal footing during the decline of the Swedish Empire. They still faced difficulties in dealing with higher Swedish authorities in Finnish and a lack of publications in Finnish. [10]

Middle Ages (c. 1150 – 1523)

Finland becomes part of Sweden

The starting point of the Swedish rule is under a large amount of uncertainty. It is connected to the efforts of the Catholic Church to expand the faith in the Eastern Baltic Sea region and to Northern Crusades.

According to the legend of Eric the Holy, written in the 1270s, the King of Sweden Eric the Holy and English bishop Henry made the first Swedish crusade to southwest Finland in the 1150s. According to the chronicle and other fabulous sources, the bishop Henry was converting people to Christianity in the areas of Finland Proper and Satakunta during the crusade. The crusade is not considered to be a real event.[13][14] Also, the Christianisation of the South-western part of Finland is known to have already started in the 10th century, and in the 12th century, the area was probably almost entirely Christian.[15] According to the Eric Chronicles the Swedish kingdom, which was only starting to form, made two crusades to Finland in the 13th century. The so-called Second Crusade against Tavastians was made in 1249–1250 and the so-called Third Crusade against Karelians in 1293. According to historical sources, the reason for the crusades besides spreading Catholic faith, were the numerous raids that Finnish tribes made to Sweden. Pope Alexander IV even accepted marriage between Swedish king Valdemar and Sophia, daughter of Danish king Eric IV, so they could better repel heathen attacks.[16][17]

By the 14th century, with the successful crusades and the partial colonization of Finnish coastline with Christian Swedish colonists, what is now Western and Southern Finland and the Karelian isthmus, had become part of Sweden, Catholic Church and the Uppsala diocese. Eastern Karelia, the Käkisalmi region and the Ladoga Karelia retained their ties to the Orthodox Church and to Novgorod.

The Treaty of Nöteborg, made in 1323 between Sweden and Novgorod, was the first treaty that defined the eastern boundary of the Swedish realm and Finland at least for Karelia. The boundary in northern Finland remained unclear. However, Sweden annexed the Finnish population on the shores of Northern Ostrobothnia in the 14th century to its realm.

Finland as part of the Kingdom of Sweden

.jpg.webp)

To help establish the power of the King of Sweden, three castles were built: the Turku Castle in Finland Proper, the Häme Castle in Tavastia and the Vyborg Castle in Karelia. In medieval times the castles were important for the defence of Finland and they also acted as government centers in Finland. The government area surrounding a castle was called a slottslän (linnalääni in Finnish). Sweden was an electoral kingdom in medieval times and the election was held at the Stones of Mora. Finland also received the right to send their representative to the election in 1362, which shows the established role of Finland as part of Sweden. The development of government and justice had a large role in the law established during the reign of king Magnus IV of Sweden.

In medieval times, the historical regions of Finland Proper and Satakunta were part of the central area of the Swedish government and retained the ties to Scandinavia they had formed already during prehistory. In Southwest Finland, Tavastia, southern Karelia there was permanent agricultural population, which gradually condensed and spread to a larger area. The spreading and establishment of the new population in Middle and North Ostrobothnia was one of the most notable events in the history of the Finnish population during the medieval ages. In Åland, the Turku archipelago and the coastal regions of Ostrobothnia and Nylandia there also was a Swedish-speaking population. In the medieval ages, peasants were by far the largest population group in Finland. A large part of the area of current Finland was a wilderness in medieval times, where people from Satakunta, Tavastia and Karelia held hunting trips, and which was inhabited by the Sámi pepole, at least some of which spoke Sami. The wilderness was not part of any government area in practical terms.

In the early times of the Swedish rule, official government documents were often written in Latin, which emphasised the role of the clergy also in secular government. The use of old Swedish as a written government language increased during the 14th century. In local governments in cities, particularly concerning international trade, the Middle Low German language was also largely used. It is however impossible to present accurate approximations of the relations of different languages in medieval times.

The countryside and cities

Unlike the situation in central Europe, peasants in Sweden were free and feudalism never developed in the Swedish realm in the proportion it did in central Europe. The local government was based on local settlements (socken) and parishes in the countryside.

In the medieval times, the concept of cities was introduced to Finland. The bourgeoisie living in the cities, such as merchants and handicraft workers, only represented a small part of the population. The most important medieval cities in Finland were Turku and Viipuri. Other cities were Naantali, Rauma, Ulvila and Porvoo. Faraway trade in Finland and other Nordic countries in the medieval times was mostly in the hands of German Hanseatic League merchants and as such a significant portion of the bourgeoisie in Turku and Viipuri were Germans. In cities, the local government was in the hands of a court led by a mayor.

The frälse

The Ordinance of Alsnö, given during the reign of Magnus III of Sweden, established a small secular frälse (Finnish: rälssi) or nobility, freed from tax, in Sweden and Finland in 1280. The spiritual frälse meant spiritual people who were exempt from paying tax to the secular government (such as priests, nuns and beggar brothers).

The parishes of the Catholic church in the area of Finland belonged to the Archdiocese of Turku. The bishop of Turku, the head of the diocese, had as well as power over the church, a large amount of secular power, and he was a member of the Privy Council of Sweden. One of the most notable medieval bishops of Turku was Magnus II Tavast, who held the office from 1412 to 1450. The spiritual frälse were the educated, literate intellectuals in medieval Finland. Its members had often attended the Turku cathedral school and some had also studied in foreign universities.

Finland as part of the Kalmar Union

_effigy_2010_(2).jpg.webp)

The Nordic Kalmar Union was founded by Queen of Denmark Margaret I in 1397. In practice, conflicts arose within the union, as the Swedish high classes with their expansion policy were interested in the east, the direction of Russia, whereas the Danish were more interested in the south – the direction of the German lands. There were also internal conflicts between the high class of individual nations. The struggle to power was not only the result of "foreign political" differences in modern parlance.

Even in the union age, Finland did not form a continuous governmental area but was divided into two separate governmental districts. Viipuri acted as a significant, sometimes almost independent centre, whereas Turku was a more integral part of the governmental area of the central authority. According to Kauko Pirinen, "In the decentralised union nation Finland was also decentralised. In practical terms, it was not a continuous political entity."

The independent position of Viipuri was evident in that although Finland was divided into two separate lawspeaker areas, Southern and Northern Finland, in 1435, Viipuri had its own independent Karelian lawspeaker area already in the 1440s, with the lawspeaker probably appointed by the chief of the Viipuri Castle. However, the Karelian lawspeaker had no authority in the Turku land court.[18]

In the union age, Finland's position as part of the realm changed. For four decades, the monarch's grasp of Finland was tighter than before. King Eric of Pomerania visited Finland twice, in 1403 and in 1407. With the union, the leading authorities in Finland also changed, as the king placed his own trustees to lead the castles. Abraham Broderson rose as the chief of the Turku Castle and the Danish Klaus Fleming was appointed as lawspeaker. Later, Klaus Lydekesson Djäkn and Krister Nilsson Vasa rose to significant positions. The bishop Magnus II Tavast was a supporter of the union power.

The community under the union times

The frälse and the clergy formed the leading political group under the union times. Finland's own frälse only rarely ruled over larger slottslän, which were mostly ruled by Swedes or Danes, sometimes even German-born men, who had however lived in Finland for decades. The Finnish frälse was mostly responsible for the lower government, military duty and especially justice. The most significant duties in the church were also assigned to sons of the Finnish frälse under the union times. However, peasants could also participate in the activities of different courts and have an effect in political decisions, such as the election of the king.

Apart from Turku and Viborg, cities under union times were small, and numbered very few. As such, foreign trade was modest. Even Viborg could not compete with Reval (Tallinn) as the centre of Russian trade. Domestic trade was economically more significant than foreign trade.

Under the union times, the Finnish government was reorganised to help the economic situation. In 1405, hundreds of farms had their tax exemption status revoked. With this, the foundation for systematic agricultural taxing was created. The crown attempted to raise tax income also by settler activities: farming fields caused tax income, whereas work in the wilderness did not. Tax income could be raised by dealing out wilderness areas for permanent population. In 1409, Turku started minting its own money, which had a different value than the money used in the rest of Sweden. They were örtugs made of silver and six penny coins. In 1407, Finland got its own supreme court, the Turku land court, which was also given governmental powers. The leaders of Finland could now decide on their country's matters in their own meetings.

The union begins to fall apart

Externally, the early times of the Kalmar Union were a time of peace for Finland. With his active foreign policy, the king Eric of Pomerania ran into conflict with the Hanseatic League, which made trade more difficult. In the 1430s, the upper class and peasant rebel movements in Sweden did not really have an effect on Finland. The opposition to the upper class caused by the minor peasant rebel movements in Finland can be explained by the expansion of the property of the crown and the frälse.[19] The best known of these rebel movements was the so-called "David rebellion" in Tavastia in 1439. It was directed at the Viikki manor.[20][21]

No one from Finland participated in the Arboga meeting in 1435. In the same autumn, the bishop Magnus II Tavast and Krister Nilsson arrived in Sweden, and in the negotiations there they participated in the discharge of the leaders of the Engelbrekt Engelbrektsson rebellion and the forming of a compromise. Krister Nilsson became the drots (seneschal) and Karl Knutsson Bonde became the marshal. After Nilsson had returned to Finland in the same autumn, rebel movements started in Sweden again.

In order to fight the rebel movements, the Finnish peasants were promised a cut in taxes in a letter dated 24 June 1436, signed by the archbishop, the drots and the marshal, under authority from the government. The stated reason was that the Finns had proven to be loyal to the realm and sworn never to take up a leader of their own, and promised not to rise up in rebellion, and accepted the leader appointed by the government. Seppo Suvanto has interpreted this so that Sweden feared that the Finnish local government would detach itself from the Swedish realm and the Finns would choose a leader of their own.[22]

Clashes of power between Finland and Sweden

The king was finally deposed in 1439, after which Sweden was ruled by a council of aristocrats. It was composed of bishops and leading noblemen. The mightiest of this group was Karl Knutsson, who was elected leader of the realm in 1438. His biggest competitor, the drots Krister retreated to Vyborg after this. After the fall of the absolutist government, Finland's connections to Denmark were severed. However, the connections to Sweden were not really strengthened but local slottslän governors mostly ruled the country.

In 1440, the Danish invited Christopher of Bavaria to their country and elected him as their king. In Sweden, negotiations were being held about the conditions of his recognition. Charles VIII of Sweden moved to Finland in the same year and took hold of the Turku and Kastelholm castles, promising to denounce his position as leader of the realm if he were to receive the whole of Finland as his county. This wish was granted, apart from Åland. However, the situation changed very quickly, and Charles VIII had to contend himself with the Vyborg slottslän. Turku returned to the power of an official appointed by the king. The king's intention was to prevent the forming of a continuous Finland.

After Christopher died in 1448, Charles VIII sailed from Vyborg to Stockholm with 800 armed men, where he was elected king (1448 to 1457), apparently because of his military superiority. His term was marked by a war with Christian I of Denmark, which caused taxes to rise also in Finland. During this period, Finland was the king's most significant support area. In 1457, the Swedish high nobility rebelled against the king, and he fled to Danzig. Christian I was elected as king of Sweden. He ruled from 1457 to 1464. However, not all people supported the new king – especially in Vyborg.

Dispute over the eastern border

The next period was marked by problems in the eastern parts of the realm. As population spread to the wilderness, border disputes and fights with Novgorod and the Karelians started. As Savonian population spread, Northern Karelia was also populated. In 1478, Novgorod was annexed to Moscow, and a new power arose beyond the eastern border. To secure the border, the Olavinlinna castle was built to protect the new settlers. The Russians viewed this as a breach of the border treaty, and open war reigned for many years until the interim peace in 1482. However, the parties could not agree on where the border was to be located.

From Axelsson to Sten Sture

.jpg.webp)

In the battle for the Swedish crown, Finnish castles were also conquered and persuaded to the union king's side. The Danish knight Erik Axelsson Tott came with his brothers to conquer castles in the 1480s, and in the end, all the castles were under the power of the Axelssons. After Erik's death he left the Vyborg, Hämeenlinna and Savonlinna counties to his brothers Ivar and Lauri, who already ruled over Raseborg. However, the formation of a continuous circle of power did not fit to the regent Sten Sture's plans. In 1481 Sten Sture arrived in Finland, all the way to Vyborg. The regent and the local governors could not come to an agreement: the regent promised tax cuts to the people; the local landowners could not accept this.

In the end of the union times, no regent had universal acceptance from all the Nordic countries any more. The King of Denmark John (reigned 1481–1513) was not accepted in the union countries, and the councils took power into their own hands. In 1483 Sten Sture received power over three counties in Finland: Vyborg, Savonlinna and Hämeenlinna. The former realm of the Axelssons became the regent's support area and Finland became an even more integral part of the central government; especially as even Raseborg came to the power of Sten Sture's supporter Knut Posse. Sture did not distribute the castles to the nobility, but ruled over them through officials dependent on him, gathering a significant amount of tax income to himself.

Unrest during the end of medieval times

In the late 15th century, previous skirmishes with Moscow escalated into a war. In 1495, the Vyborg Castle was sieged. People from Western Finland were also drafted to war. In threatened areas, all people over 15 years of age were called to arms, and in addition, German mercenaries and people from Sweden arrived in the country. The Russian attacks stretched from Karelia to Ostrobothnia, Savonia and Tavastia. Peace was made in 1497.

In the same year, the Privy Council of Sweden deposed Sten Sture as regent. However, the Finnish slottsläns remained under his control. A civil war followed, where King John beat the regent's troops, becoming King of Sweden himself (1497–1501). In 1499, Sture had to renounce his areas in Finland. In 1503, Svante Nilsson Sture (reigned 1504–1512) was elected as regent, and the Finnish leaders swore their loyalty to him. In a meeting held in Turku, the people showed their support for his position. However, the unanimity was only specious, as part of the leaders of Finland supported their own political standpoint together with Sten Sture's family. Their goals have remained somewhat unclear. However, national history has emphasised the role of eastern politics in the disagreements.

The age of Vasa (1523–1617)

The final battles of the union

The final times of the union were a time of unrest in most of Finland, not only in Vyborg. In the late 16th century, the Danish went on pillages on the Finnish coast, and the pirate captain Otto Rudi robbed Turku and its cathedral's treasures. As the Danish union king Christian II of Denmark came to power, in his coronation he had tens of Swedish noblemen beheaded. This was called the Stockholm Bloodbath. The Swedish nobleman Gustav Vasa rose up to oppose the union king and won the peasants on his side. The German Hanseatic merchants also supported Gustav Vasa and provided him with weapons and money. The Finnish-born brothers Erik and Ivar Fleming conquered the Finnish castles for Gustav Vasa and drove the Danish away from Finland in 1523. The age of the Nordic union came to an end, and Gustav Vasa became king of Sweden and Finland.

An early modern state is born

During the reign of Gustav Vasa, a continuous Swedish realm started to form. He managed to suppress the regional communities who had been driving their own politics. In turn, the reformation suppressed the church. The high nobility, already weakened by the bloodbath, was now attached to support royal politics. However, the governing was still done in the medieval tradition: the king had numerous noblemen and scribes to help him, but these were not really officials. Also the government did not have a clear distinction of jobs, but tasks under the king's service changed according to the situation. In the 1530s, Gustav Vasa started to bring in German government officials to the country, along with whom new visions of royal power arrived in Sweden. During the 1544 Västerås Diet, the royalty was changed to hereditary and Gustav Vasa's eldest son Erik was named heir to the throne.

The crown's local government concentrated in the hands of officials after land grants had been revoked. Their jobs were numerous, but collecting taxes was one of the most important ones. During Gustav Vasa's reign, tax collecting switched to literal government; first, systematic land documents (of ownership of land) were kept to help in taxation, other kinds of catalogues and literal accounts soon followed. The officials were also responsible for repopulating vacated houses, providing transport and roads. The officials also had to prevent illegal trade and handwork practiced in the countryside. Also overall peacekeeping and justice work belonged to the officials' duties – this way the crown's share of tax and fine income could be secured. Enhancing government raised the crown's tax income by tens of percents.

The war against Russia

Continuing conflicts with Russia were still significant in Finnish foreign politics. In the start of Gustav Vasa's reign, negotiations were held in an attempt to regain an idea of where the borderline went. The Swedish tried to postpone checking the borderline for as long as possible, and despite temporary agreements, conflicts and raids on both sides continued. In a nobility meeting held in Vyborg in 1555, the king was advised to go to war. The attack resulted in a counter-attack by Ivan the Terrible from the direction of Vyborg and Savonia. Negotiations held from 1556 to 1557 resulted in an interim peace lasting 40 years. There was a plan to hold a new negotiation about the borderline in 1559, but this never happened.

Misconduct by the nobility

In war times, the king had spent a long time in Finland. There he ordered an extensive investigation of misconduct by the nobility. This investigation resulted in the so-called Jakob Teit complaint list, which is a significant source of community history in the 16th century. In summer 1556, the king made Finland into its own duchy, and named his son John as its ruler. Gustav Vasa died in September 1560. Erik XIV of Sweden succeeded him on the throne.

The reign of Erik XIV

Erik XIV was crowned as king in 1561. He attempted to strengthen the monarchy even more in regard to the nobility and also to his brothers. To weaken their position, Erik founded new counties and baronships to divide the power of dukes. In Finland, the king's politics also resulted in new lawspeakers being appointed to the country. In 1561 the king approved the so-called Arboga articles at a diet, which submitted the dukes to the king's control and stripped them of a chance for independent foreign politics.

Destroying the position of John, the duke of Finland, was important to the king. As John's duchy, Finland became a "feudal minicountry" subject to the realm, with its own chancery, tax chamber and council, which could be compared to a state council. John's prerogatives in Livonia were also in conflict with the king: through a planned marriage with Catherine Jagiellon, John could receive numerous castles under his power in Livonia. At the same time, Erik XIV was being driven to war with Poland because of his expansion politics directed at Livonia. In 1561, the Tallinn city council had already given the city to the protection of the king, and during the same spring the Virumaa and Harjumaa nobility also resigned from the German knighthood.

The struggle for power

After the conflict had intensified, the king assembled a diet in 1563, where John was sentenced to death. The development led to the siege of the Turku Castle in summer 1563. After conflicts and bombardments, the castle surrendered on 12 August 1563, after which the luxury of the castle was destroyed, the duke and his wife were arrested and sent to Sweden for imprisonment. In the 1560s, Swedish foreign policy was marked by war against Poland in the Baltics. As well as this, Erik XIV was driven to war against Denmark-Norway and Lübeck. This required good relations to the east: concentrating military forces elsewhere required good relations towards Moscow. Erik XIV's era ended in 1568 after the nobility rose up against the king. This time even the Finnish nobility was on the side of the rebels, both old supporters of John and Erik's trusted men. The Turku Castle fell under the power of the rebels. Erik spent the next years in prison, until he was sentenced to death and poisoned in 1577.

The long wrath

Under the reign of John III of Sweden, the border conflicts at the border of Käkisalmi county led to a new war (1570–1595), which is now known as the "25-year war". It was mostly a brutal war with guerilla warfare on both sides. In its beginnings, the war was well organised, and there was a truce on the Finnish front from 1573 to 1577. In the middle of the decade the peasant conflicts started again: the Karelians attacked in the direction of Oulujärvi and Iijoki, forces from Southern Finland travelled across the Gulf of Finland. At the end of the decade, organised warfare started again with an attack to Narva (1579) and the conquest of Käkisalmi in 1580. Narva was conquered the next year, after which negotiations led to an interim peace lasting until the year 1590. Despite the interim peace, guerilla warfare continued on both sides of the eastern border, which led to Kainuu and Northern Ostrobothnia being largely deserted in the 1580s. Led by Pekka Vesainen, the Ostrobothnians made vengeance trips to Viena Karelia. The war ended in 1595 with the Treaty of Teusina.

A new struggle for the throne

After John III died in 1592, the throne was left vacant. There were two candidates for his successor: Sigismund and the duke Karl. The question of the monarchy was entwined with church politics: in the time of the counter-reformation in Europe Sigismund was a Catholic, which made his position even more problematic in Lutheran Sweden. In 1593, Sigismund arrived in the country to be crowned. He took his oath as a ruler in the autumn of the next year. At the same time, he accepted the Lutheran line of the Uppsala estate and church meeting (1593). With Sigismund's coronation, a personal union between Sweden and Poland, lasting a few years, was born; Sigismund was king of Poland until 1632.

After the king returned to Poland, conflicts arose among the nobility about Karl's position as a regent. In this conflict, Finland's leader Klaus Fleming sided with the king. At the Arboga diet in 1597, Karl was still named as regent. At this time, he declared his opponents, especially Klaus Fleming, to be rebels.

Justice becomes stricter

In general, secular courts in Europe during the start of the New Age in the 16th and 17th centuries started using the so-called "Law of Moses", that is to say, some parts of the Bible. According to the Law of Moses, witchcraft and magic was forbidden, and for example blasphemy, swearing, betraying one's parents, perjury, killing, demanding too high interest, false testimony and numerous sexual crimes could be punished by death. The Law of Moses became a general guide of justice in the Swedish realm in 1608 and remained in force until the new law of the realm in 1734. However, the law was often not used to the full extent of its cruelty, and death penalties were replaced with lesser penalties in about half of the cases.[23][24]

The peasant unrest in the 16th century and the Cudgel War

Unrest increased among the peasants during Gustav Vasa's reign, because of both heightened taxes and the struggle for power amongst his sons. The unrest resulted in the Cudgel War from 1596 to 1597. It ended bloodily, with the army beating the Ostrobothnian and Savonian peasants, armed by cudgels, spears and bows. The rebellion in Finland was directed at the nobility in power and especially at Klaus Fleming. The rebels sought help from the duke Karl who had been trying to usurp the throne. According to current research, the reasons for the rebellion included strain left from the 25-year war, financial setbacks and suffering caused by the castle camp system. Researchers disagree on how big an effect the duke Karl's leading the rebels against Klaus Fleming had on the outbreak of the Cudgel War.[25][26]

The Great Power age (1611–1721)

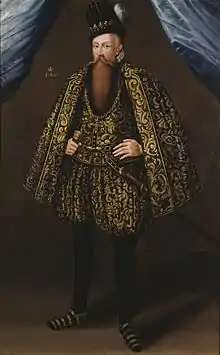

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

The Treaty of Stolbovo

_en2.png.webp)

From 1604 to 1611, the duke Karl of Södermanland was king Charles IX of Sweden. During his reign, the realm was almost constantly at war with Russia and Poland, especially about the ownership of the Baltic lands of Estonia and Livonia. Also, a war with Denmark was fought from 1611 to 1613, resulting in a loss for Sweden. After Charles IX died, his son Gustav II Adolf inherited the throne. The realm was in a bad state and Sweden had to sign a peace treaty with Denmark in 1613. The Treaty of Stolbovo was signed with Russia in 1617, which resulted in the Käkisalmi county, Nöteborg and part of Ingria being annexed into Sweden.

Modernisation and renewals

Under the leadership of the king and the chancellor of state Axel Oxenstierna, significant renewals were made in Sweden and Finland once the foreign political situation had calmed down. The army and the military organisation were reorganised especially based on the model of the Dutch Mortis of Orania. The realm received a new form of government and was divided into counties. Also, a Governor General was appointed to Finland in the 17th century to improve the conditions in the country. Governor Generals of Finland included Niels Bielke and count Per Brahe the Younger, whose official residence was the Turku Castle. During the superpower age, new cities were founded in Finland, as well as the Turku court of justice and in 1640, Finland's first university, the Royal Academy of Turku.

The Thirty Years' War

In the Baltics, Sweden was still at war with Poland, and in 1629 the temporary Truce of Altmark was made. In Germany, Gustav II Adolf joined the Thirty Years' War between the Catholic emperor and the Protestant princes in 1630 after making landfall in Northern Germany. Sweden's aim in the war was to support the German Protestants and strengthen its own position. However, Gustav II Adolf died in the Battle of Lützen in 1632 and his daughter Christina succeeded him on the throne while still a minor. In practice, the realm was ruled by a caretaker government led by Axel Oxenstierna. In the Peace of Westphalia that had ended the Thirty Years' War in 1648, Sweden secured its position as a superpower. However, the Thirty Years' War and other conflicts in the superpower age drained Sweden's and Finland's resources badly. A significant part of the peasants had to serve in the army and the navy, and many of them died in service.

From the wars to the age of peace

During Christina's reign from 1632 to 1654, a large amount of lands were given as feudal lands to the nobility. The nobility had the right to collect taxes on their lands, which made the crown's financial position more difficult. After Christina had renounced the crown, Charles X Gustav of Sweden followed her on the throne and ruled over the Swedish realm from 1654 to 1660. Charles X died in 1660, and was followed by Charles XI of Sweden, during whose reign from 1660 to 1697, a large reduction was made, which returned most of the feudal lands to the crown. Charles XI weakened the power of the nobility and ruled the realm as an autocrat. Charles XI's reign meant a long time of peace for Finland. The Protestant clergy was responsible for teaching literacy to the people, and clerical life was dominated by religious purism. From 1695 to 1697 Finland was devastated by the Great Famine, which resulted in a significant part of the population dying of hunger and illnesses.

The Great Northern War

During the reign of Charles XI's successor Charles XII of Sweden, the Great Northern War erupted in 1700, resulting in Sweden losing its superpower position. The cause of the war was an alliance against Sweden made by its enemies Denmark, Russia, Poland and Saxony. In the 1617 Treaty of Stolbovo, Russia had lost its connection to the Baltic Sea. The renovation-minded tsar Peter the Great sought to reopen a connection to the Baltic Sea for Russia, so that its connections and trade to Western Europe would become easier.

Although Charles XII managed to beat Denmark, Russia's attacking troops (in the Battle of Narva) and Poland, one at a time, the Swedish finally suffered a decisive defeat to the Russians in the Battle of Poltava in 1709. After this, the king fled to Turkey and the realm was open to an enemy attack. Vyborg was conquered in 1710, and the Russians occupied the rest of Finland after the Battle of Pälkäne in Pälkäne, the Battle of Storkyro in Ostrobothnia and the Battle of Gangut in front of Hanko by 1714. The Russian invasion period from 1714 to 1721 is commonly called the Greater Wrath. The occupation period was destructive to Finland. Thousands of people were killed and even more were sent to Russia, and a large part of the country's officials and clergy fled to Sweden. The Great Northern War and the Greater Wrath ended in the Treaty of Nystad in 1721. In the treaty, Ingria, Estonia, Livonia, the Käkisalmi county and Vyborg were annexed to Russia. The part of Karelia annexed to Russia is commonly called Old Finland. Russians also sometimes enslaved large parts of the Finnish population, both Swedes and Finns. Swedish boys were praised for their high literacy and almost all Swedish slaves were able to read. They were considered luxury goods by Russian and Ottoman nobles for their beautiful eyes and blonde hair. Slavery was banned in Sweden in the 14th century. But the primitive ruling system in Russia enabled slavery to remain economically feasible. During the Swedish and Russian wars, Finns were frequently sold into slavery by Russian Cossacks. Due to the Swedish state, higher morals and political pressure concerning slavery created a demand to stop the trade of Finnish and Swedish slaves in Russia among Russian noblemen.[27][28]

Karl XII also spoke some Finnish with the Finnish part of the Swedish military.[29]

Proposals about the Swedification of Finland

During the Great Northern War, professor Israel Nesselius of the Turku Academy wrote several articles about the fate of the Finnish language. In one of his articles, he proposed the Swedification of Finland by teaching the Swedish language to the people of Finland and by bringing more population from Sweden to strengthen and expand the Swedish population. He thought that the Finnish language was so peculiar that only a couple of villages on the border of Lapland should be allowed to keep their language. According to Nesselius, this could be handled by bringing army recruits from Skåne as immigrants to Finland to defend the country against Russian attacks. In return, Finnish soldiers could be moved to Skåne as farmers and to defend the border against Denmark. Also the Finnish sauna custom – "that constant sauna bathing" – should be eliminated as it wasted firewood and was different from the Swedish customs.[30]

In the 18th century, there was discussion about bringing Swedish population as immigrants to Finland in a different context. The idea was to kill two birds with one stone. On one hand, areas suffering from overpopulation, such as Dalarna County, would be addressed. On the other hand, farming could be extended to sparsely-populated areas in Finland. The Swedish official and economist Ulrik Rudenschöld specified in 1738 that this kind of migration would help develop bilingualism in the eastern parts of the realm.[30]

At the Diet of 1738, the president of the court Samuel Åkerhielm the younger started a discussion about languages at the discussion of the great secret court. According to Åkerhielm, the peculiarity of the eastern part of the realm was exaggerated and the use of the Finnish language was a lesser problem than what had been claimed. According to him it was short-sighted to demand knowledge of both languages in order to get official posts in the eastern parts of the realm. If posts in the eastern parts of the realm required knowledge of Finnish, which in practice meant being born in Finland, the same requirement had to be also in the western parts of the realm. He saw this as causing envy and striking a wedge between "our two nations", which would harm the realm. However, he saw it as an unchangeable fact that the people in the realm spoke two different languages. Jakob Faggot continued the same thought in his letter in 1745, but according to him, the Finnish people should be taught Swedish so they could become as good Swedes in their language as they were in their mind.[31]

The Diet of 1746–1747 saw the increase of the use of the Swedish language in Finland as favourable. It was seen as "strengthening the trust between two peoples". However, even the proponents of this matter saw its practical fulfilment as impossible.[30]

The Age of Liberty and the Gustavian Age (1721–1809)

Power away from the king

.png.webp)

In the Swedish realm after Charles XII, the estates took power away from the king in the 1719 and 1720 governments and the age of autocracy changed into the age of estate rule (the "Age of Liberty"). Economy and science progressed during this age, but on the other side, power politics among parties caused problems. France and Russia gained power in Sweden by financing competing parties, which were called the Caps and the Hats.[32]

Finnish became an official language of the Swedish administration in Civil Code of 1734. So monolingual Finnish parliamentarians could always use Swedish translators at the Riksdag of the Estates and use Finnish with local administrators. It was a new liberal reform made to modernize the Swedish state.[33] The reform had been proposed earlier in the 18th century but the invasion of Finland by Russia delayed the Swedish government from passing the new law until 1734. The law is also the oldest law both partially still in use in both Finland and Sweden. It was the first time in Sweden and Finland's history when the king and Riksdag created a unitary legal code applied to the entire country. It was also translated to Finnish so that Finnish speakers would understand.[34]

The Hats' War

The Hats' rise to power in the 1738–1739 diet led to a Russophobic foreign policy, which was a disadvantage for Finland. An attack war against Russia, known as the Hats' War, erupted in 1741. Sweden suffered a defeat in the battle of Lappeenranta in the same year, and the later stages of the war fared no better for it. In 1742, the Swedish army withdrew from a Russian attack and surrendered. Russia occupied Finland again from 1742 to 1743. This occupation period is known as the Lesser Wrath. The Russian empress Elizabeth spread a manifesto in 1742, urging Finns to abandon Sweden and form an autonomous state protected by Russia. However, after the occupation of Finland, promises of autonomy stopped.[35] The occupation ended in the Treaty of Åbo. The occupation during the Lesser Wrath did not cause as much damage as the longer and more violent Greater Wrath a couple of decades earlier.

Thoughts in the new age

After the war, the mercantilist principles in the trade led to the financial gain from tar and shipbuilding being left in Stockholm. In 1760, Anders Chydenius, the vicar of Kokkola, started demanding freedom of trade and speech.[32] During the last decades of the 18th century, interest to Finnish history and Finnish national poetry arose in the Royal Academy of Turku, especially because of Henrik Gabriel Porthan, the "father of Finnish history".[36] Of the researchers, Eino Jutikkala says: "People in various regions and of various estates in Finland in the late 18th century consciously considered themselves as Finnish as opposed to the Swedish who lived on the other side of the sea."[37]

The Swedish clergy demanded universal literacy. Finland and Sweden had the highest literacy rates in comparison to other European nations due to Lutheran priests demanding pupils and farmers to read the Bible, which led to quick development in reading skills. Already in the 1660s religious school classes could read with good scores for the time in comparison with other European nations. Charles XI of Sweden believed that an illiterate man could never become a full member of the Swedish church. Therefore, he could never join the church and would never marry if he were not a member of the church. In Carl av Forsell's official examinations of Finland and Sweden, he found high literacy an essential part of religious education for commoners in both countries in 1833.[38] The first Finnish papers only started to appear in the late 18th century.[10]

The restless reign of Gustav III

In 1772, after Gustav III of Sweden had seized power, a new constitution was made, giving power back to the king. The age tried to get rid of mercantilism. Freedom of speech and freedom of religion expanded. Finnish officers trusted the king less, because the nobility lost their power to the king, who was supported by the people. Some high-ranking soldiers moved to serve in Russia.[32]

From 1788 to 1790, the so-called Gustav III's war, started by Gustav III, was fought between Sweden and Russia. Sweden was also confronted by Denmark. The officers in the Anjala conspiracy, among others, opposed the war. Despite a decisive marine victory at the Battle of Svensksund, Sweden did not gain any new territories in the Treaty of Värälä. The Union and Security Act of 1789 strengthened the king's power even more. With the war, the nobility grew even more bitter towards the king, and this eventually led to the king's murder in 1792.[32]

Sweden loses Finland

The Finnish War was fought from 1808 to 1809 between Russia and Sweden. The reason for the war were the Treaties of Tilsit made between Russia and France on 7 July 1807. In the treaties, France and Russia had become allies and Russia had promised to pressure, with armed force if necessary, Sweden and other countries to join the Continental System against the United Kingdom, an embargo that France would have used to strengthen its position against the maritime power of the United Kingdom.

The last Grand Duke of Finland during the Swedish era was Gustav IV Adolf's second son Karl Gustaf, who was born in 1802 and died as an infant in 1805.[39] Gustav IV Adolf of Sweden, the last Swedish king of Finland, ironically was one of few Swedish kings to learn Finnish. He also became popular among the people in Finland when he was nine years old and spoke Finnish with local Finns during his visit to Finland. Gustav travelled to Finland on several vacations because of his extensive knowledge of the language. But he was considered an incompetent ruler when it came to international politics and his management of Swedish Armed Forces.[40][41]

The Swedish attitude towards Finland

The Swedish thought Finland was far away from the centre of power and from Stockholm. From Stockholm's point of view, inhabitants of the eastern part of the realm were seen as "the people of that country". Royal letters about matters relating to Finland told that information had been gathered "from that area" and people came from Finland "over here to Sweden". Landlords in Finland could be called to come "here to Sweden". People who ended up in Finland from Sweden felt they had arrived in a strange and foreign environment. For example, troops from Småland stationed in Vyborg rebelled in 1754 because they had not received the benefits usually given to Swedish troops stationed abroad. They also felt that they were not required to defend Finland as it was not their home country. Governor-General Niels Bielke, who had arrived in Turku in the 1620s to strengthen the rule of the central power, described Finland as a repulsive land of barbarians, and the bishop Isaacus Rothovius felt he was "in the middle of scorpions and barbarians".

Professor Michael Gyldenstolpe, who had moved from Växjö to Turku in 1640, repeatedly wrote to Per Brahe the Younger that as a Smålandian, he was "a foreigner in this country" and he felt sorry for "the moment he arrived in this country". Carl Johan Ljunggren, who had served in the Västmanland regiment in the Finnish War in 1808 described the Swedish-speaking people of the coast as similar to the common people of Sweden, but the peasants in the inner country as looking repulsive and impolite. They wore dome-shaped caps on their heads and leather boots on their feet. Living in smoke cabins had made their skin a dirty shade of brown and they spoke "incomprehensible gobbledygook".[42]

During the period after the loss of the great Swedish power status and due to the potential growth of Finnish nationalism, a need among the Swedish nobles and historians for a common Swedish and Finnish identity arose. Instead of treating the Finnish culture and history as inferior, the Swedish historians and nobles sought to make Finnish culture appear more connected to the history of Sweden. The Swedish state (during the period) advocated that the Finns were the original Inhabitants of Sweden. According to Johannes Messenius, a Finnish king was the first monarch to rule Scandinavia. This thesis that the Finns were the first to rule Scandinavia launched during the 16th century, as previously mentioned this was to create a combined Finnish and Swedish identity. This idea conflicted with previous historical consensus which ruled that the Swedes settled Scandinavia before the Finns arrived.

The first king of Scandinavia was allegedly (according to Messenius) the first monarch of the Fornjót dynasty. This first king was of Finnish descent. Finland was the first kingdom in Scandinavia according to Sven Lagerbring and Johan Ihre.[43]

Swedish historians and politicians during the Great power era sought to make Sweden appear more prestigious. Considered being connected with a great and glorious past was deemed of great importance. Swedes and Finns being related to ancient peoples with a proud history was invented for Sweden to appear more prestigious among foreign nobles. Swedish historians believed Finns were still speaking Hebrew and were considered a lost tribe of Israel. Olof von Dalin in the 18th century was one of the advocates for Finns being a lost Scythian, Greek Hebrew tribe. Von Dalin stated in 1732: "they are a mix of Scythians, Greeks and Hebrews". Finns were to have been the creators of the first advanced civilization according to some Swedish historians.[10] He describes Finns as simple people that live simple lives but are as close to God as they can be: very happy and satisfied with their easy life and closeness to nature and God.[44] Von Dalin also claims Finns are as fast as trolls on their skis moving incredibly fast, but that their clothing style looks somewhat wild in comparison with Swedes making them look like trolls.[45]

According to von Dalin the Finnish and Swedish elite even before the Swedish crusades had close friendly connections but also fought some wars. Neurer or Finns, the first inhabitants of Scandinavia, according to Dalin already had an independent Finlandic kingdom with their own courts and kings before the Old Uppsala kingdom was created. The Finns, according to von Dalin, took part in the Gothic migration from Sweden into the Roman empire. When the East Geats together with the Finns made up the ancestors of the Gothic migration from Sweden.[46]

This noble Finnish past was also created by a geopolitical need to create a common identity between Swedes and Finns against Russia. The idea of Finns being a lost tribe of Israel became a consensus among Swedish historians. The Finnish language was ancient Hebrew according, to the Swedish priest Olof Rudbeck. Finnish was also, according to Rudbeck, related to the Gothic language. The idea of Finnish being ancient Hebrew soon had support among many Swedish historians. The German nationalist awakening claimed Germanic peoples or Swedes made up the bulk of early Swedish civilization. It got rejected by Swedish mainstream historians that meant it was Finnish tribes that first reached Sweden. The idea that Finnish was Hebrew was later abandoned by a majority of mainstream historians, though some stuck to the theory. But the Finns being the first people in Sweden stuck among the majority of historians.

When Finland was lost, the ideas of Finns being the original native population of Sweden and a lost tribe of Israel was gradually abandoned. It was abandoned since there were no geopolitical benefits for building a common identity any longer. New ideas began to develop; instead of the Swedes being mixed with Finnic peoples, the idea arose that Swedes were completely culturally clean both in history and archaeology. Especially due to the shared Viking history with Norway and Denmark, after the Union between Sweden and Norway, interests in regaining Finland ended. Sami and Finnish archaeological findings in Sweden began to be denied even though they had been widely examined and studied before. Even though there were clear traces of Finnic tribes in some parts of Sweden, archaeologists ended their research on Finnish history in Sweden. Some bitterness in Sweden remained in the hope of regaining Finland in a war with Russia, but the idea of Scandinavism or Scandinavian unification like in Germany and Italy started to develop among the Nordic language-speaking populations in Scandinavia in the 19th century.[10]

References

- Tarkiainen, Kari (2010). Ruotsin itämaa (in Finnish). Porvoo: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland. pp. 167–170. ISBN 9789515832122.

- Haggren, Georg; Halinen, Petri; Lavento, Mika; Raninen, Sami; Wessman, Anna (2015). Muinaisuutemme jäljet (in Finnish). Helsinki: Gaudeamus. pp. 420–421.

- Tarkiainen, Kari (2010). Ruotsin itämaa (in Finnish). Porvoo: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland. pp. 134–136.

- Tarkiainen, Kari (2010). Ruotsin itämaa (in Finnish). Porvoo: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland. pp. 143–147.

- Kemiläinen, Aira (2004). "Kansallinen identiteetti Ruotsissa ja Suomessa 1600-1700-luvuilla". Tieteessä Tapahtuu (in Finnish). Tieteessä tapahtuu 8/2004. 22 (8): 25–26. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- Engman, Max (2018). Kielikysymys (in Finnish). Helsinki: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland. p. 32. ISBN 978-951-583-425-6.

- "Suomi osana Ruotsin valtakuntaa". finnica.fi (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 17 February 2020.

- Tarkiainen, Kari (2010). Ruotsin itämaa (in Finnish). Helsinki: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland. p. 235. ISBN 978-951-583-212-2.

- Englund, Peter (2003). Suuren sodan vuodet, Finnish-language version, introduction. Helsinki, WSOY. ISBN 9789510279403 See also: finnica.fi Archived 17 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- Jensen, Ola W. (2009). "Sveriges och Finlands gemensamma forntid – en ambivalent historia: idéer om forntiden, kulturarvsbegreppet och den nationella självbilden före och efter 1809" (PDF). Fornvännen. Journal of Swedish Antiquarian Research (in Swedish). 104 (4). ISSN 0015-7813. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2021.

- Georg Haggren, Petri Halinen, Mika Lavento, Sami Raninen ja Anna Wessman (2015). Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Helsinki: Gaudeamus. p. 376.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Uino, Pirjo (1997). Ancient Karelia. Helsinki: Suomen muinaismuistoyhdistyksen aikakausikirja 104. p. 201.

- Zetterberg, Seppo, ed. (1987). "Eerik-kuningas ja Henrik-piispa Suomessa" Suomen historian pikkujättiläinen (in Finnish). Helsinki: WSOY. pp. 48–52. ISBN 951-0-14253-0.

- Tarkiainen, Kari (2010). Ruotsi itämaa (in Finnish). Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland. ISBN 978-951-583-212-2.

- Haggren, Georg; Halinen, Petri; Lavento, Mika; Raninen, Sami; Wessman, Anna (2015). Muinaisuutemme jäljet (in Finnish). Helsinki: Gaudeamus. p. 343.

- Linna, Martti, ed. (1989). Suomen varhaiskeskiajan lähteitä (in Finnish). Historian aitta. pp. 82–85. ISBN 9789519600611.

- Lönnroth, Harry; Linna, Martti (2013). Eerikronikka (in Finnish). Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. pp. 71–72.

- Holappa, Veli: Verot ja oikeuslaitos 1500–1600 -luvulla: Keskiaikainen oikeudenkäyttö Archived 14 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Katajala, Kimmo (2002). Suomalainen kapina (in Finnish). Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. p. 136. ISBN 9789517463065.

- Ylikangas, Heikki (2005). Nuijasota (in Finnish). Helsinki: Otava. p. 174. ISBN 9789511142539.

- Katajala, pp. 124–137.

- Salminen, Tapio: Suomen linnojen ja voutikuntien hallinto 1412–1448, pp. 37–38. Master's thesis, University of Tampere 1993.

- Nenonen, Marko; Kervinen, Timo: Finnish witch trials in synopsis (1500–1750) Archived 28 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Jumalan laki astuu voimaan". Archived from the original on 28 June 2008. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- Katajala, Kimmo. "Miksi nuijasota syttyi Pohjanmaalla?" (PDF) (in Finnish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 May 2016.

- Ylikangas, Heikki (1997). Nuijasota (in Finnish). Helsinki: Otava. pp. 358–359. ISBN 951-1-14253-4.

- "Slave trade continued in Russia even after the Middle Ages". EurekAlert!. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Dash, Mike (15 January 2015). "Slavery on the Steppes: Finnish children in the slave markets of medieval Crimea". A Blast From The Past. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- "Karl XII av Pfalz-Zweibrücken – Historiesajten". historiesajten.se (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Villstrand, Nils Erik (2012). Valtakunnanosa (in Finnish). Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-951-583-256-6.

- Villstrand, Nils Erik (2012). Valtakunnanosa (in Finnish). Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-951-583-256-6.

- "Suomi – Vapauden ja hyödyn aika". fennica.fi (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 5 August 2020.

- Vahtola, p. 162.

- Mattila, H.E.S. (29 June 2015). "Oikeustiede: kodifikaatio: laajempi kuvaus". Tieteen Termipankki (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- "Suomi". Pieni tietosanakirja (in Finnish). 1925–1928. pp. 478–490. Archived from the original on 16 November 2019.

- "Porthan-Seura" (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 1 November 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- Jutikkala-Pirinen: Kivikaudesta Koivistoon, 1989, pp. 194, 196, 205, the same in the 2002 edition.

- Graff, Harvey J. (2009). Understanding Literacy in Its Historical Contexts: Socio-Cultural History and the Legacy of Egil Johansson (PDF). Alison Mackinnon, Bengt Sandin, Ian Winchester. Lund: Nordic Academic Press. pp. 28–29, 34, 47. ISBN 978-91-87121-76-0. OCLC 797917608. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2021.

- Cederberg, A. R. (1947) [1942]. "Juva". Suomen historia vapauden ajalla, I-II (in Finnish). WSOY. p. 114.

- Chrispinsson, John (2014). Den glömda historien: om svenska öden och äventyr i öster under tusen år [new edition] (in Swedish). Norstedts. ISBN 9789113068541.

- Mäntylä, Ilkka (2014). "Gustav IV Adolf". Biografiskt lexikon för Finland (in Swedish). electronic edition: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021.

- Villstrand, Nils Erik (2012). Valtakunnanosa (in Finnish). Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland. pp. 23–28. ISBN 978-951-583-256-6.

- Jensen, Ola W. (2009). "Sveriges och Finlands gemensamma forntid – en ambivalent historia: idéer om forntiden, kulturarvsbegreppet och den nationella självbilden före och efter 1809" (PDF). Fornvännen (in Swedish). 104 (4): 290. ISSN 0015-7813. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2021.

- von Dalin, Olov (1747). Svea Rikes historia. Första Delen (in Swedish). p. 280. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- von Dalin, Olov (1747). Svea Rikes historia. Första Delen (in Swedish). p. 276. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- von Dalin, Olof (1750). Svea Rikes Historia. Andre Delen (in Swedish). pp. 100–104. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

Bibliography

- Vahtola, Jouko: Suomen historia: Jääkaudesta Euroopan unioniin. Otava, 2003, Helsinki (4th edition 2005). ISBN 951-1-17397-9.

- Zetterberg, Seppo (ed.): Suomen historian pikkujättiläinen. WSOY, 1987, Helsinki. ISBN 951-0-14253-0.

- Korhonen, Arvi (ed.): Suomen historian käsikirja, previous part. WSOY, 1949, Porvoo – Helsinki.

- Karonen, Petri: Pohjoinen suurvalta: Ruotsi ja Suomi 1521–1809. WSOY, 1999, Helsinki. ISBN 951-0-23739-6.

- Pohjolan-Pirhonen, Helge: Suomen historia 1523–1617. WSOY, 1960, Porvoo – Helsinki.