Politics of Finland

The politics of Finland take place within the framework of a parliamentary representative democracy. Finland is a republic whose head of state is President Sauli Niinistö, who leads the nation's foreign policy and is the supreme commander of the Finnish Defence Forces.[1] Finland's head of government is Prime Minister Petteri Orpo, who leads the nation's executive branch, called the Finnish Government.[2] Legislative power is vested in the Parliament of Finland (Finnish: Suomen eduskunta, Swedish: Finlands riksdag),[3] and the Government has limited rights to amend or extend legislation. The Constitution of Finland vests power to both the President and Government: the President has veto power over parliamentary decisions, although this power can be overruled by a majority vote in the Parliament.[4]

Politics of the Republic of Finland | |

|---|---|

| |

| Polity type | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Constitution | Constitution of Finland |

| Legislative branch | |

| Name | Eduskunta/Riksdagen |

| Type | Unicameralism |

| Meeting place | Parliament House |

| Presiding officer | Jussi Halla-aho, Speaker of the Parliament |

| Executive branch | |

| Head of State | |

| Title | President |

| Currently | Sauli Niinistö |

| Appointer | Popular vote |

| Head of Government | |

| Title | Prime Minister |

| Currently | Petteri Orpo |

| Appointer | President |

| Cabinet | |

| Name | Finnish Government |

| Current cabinet | Orpo Cabinet |

| Leader | Prime Minister |

| Appointer | President |

| Headquarters | Government Palace |

| Ministries | 12 |

| Judicial branch | |

| Name | Judicial system of Finland |

| Courts | General Courts |

|

|---|

The judiciary is independent of the executive and legislative branches. The judiciary consists of two systems: regular courts and administrative courts. The judiciary's two systems are headed by the Supreme Court and the Supreme Administrative Court, respectively. Administrative courts process cases in which official decisions are contested. There is no constitutional court in Finland: the constitutionality of a law can be contested only as applied to an individual court case.

The citizens of Finland enjoy many individual and political freedoms, and suffrage is universal at the age of 18; Finnish women became the first in the world to have unrestricted rights both to vote and to run for public office.

The country's population is ethnically homogeneous with no sizable immigrant population. Few tensions exist between the Finnish-speaking majority and the Swedish-speaking minority, although in certain circles there is an unending debate about the status of the Swedish language.

Finland's labor agreements are based on collective bargaining. Bargaining is highly centralized, and often the government participates to coordinate fiscal policy. Finland has universal validity of collective labour agreements and often, but not always, the trade unions, employers, and the Government reach a national income policy agreement. Significant Finnish trade unions include SAK, STTK, AKAVA, and EK.[5]

The Economist Intelligence Unit rated Finland a "full democracy" in 2022.[6]

History

Autonomous but under Russian rule

A Finnish political identity and distinctively Finnish politics first developed under the Russian rule in the country from 1809 to 1917. During the era Finland had an autonomous position within the Russian Empire with its own legislative powers. However, all bills had to be signed into law by the Russian Emperor who was the Grand Duke of Finland. Also, military power was firmly in Russian hands. Previously Finland had been a part of Sweden and did not have any political institutions of its own, rather people of Finnish ethnicity participated in Swedish politics.[7]

Independence and civil war

The Finnish Senate issued a declaration of independence on 6 December 1917, after Russia's second revolution in October 1917. The Council of People's Commissars of Soviet Russia, chaired by Lenin, recognized Finland's independence on 31 December 1917, and soon after that many other states followed.

On 28 January 1918, a civil war broke out that ended in the victory of German-backed Whites against Bolsheviks-backed Reds. In the same year the volunteers made some armed expeditions into Soviet Russia, including Karelia, and also Estonia. The Finnish Civil War was part of the First World War. The war was fought between the Finnish Senate, i.e. the forces led by the government, and the Finnish People's Delegation, from 27 January to 16 May 1918. The Senate forces were called Whites and the People's Delegation forces Reds.

Second World War

During the Second World War, Finland fought three wars: the Winter War, the Continuation War and the Lapland War.[8]

According to the ceasefire agreement, in addition to the territorial losses following the Winter War, Finland had to hand over Petsamo and lease Porkkala as a base for 50 years. War reparations were set at USD 300 million. The terms of the ceasefire agreement were finally confirmed in the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty.

Urho Kekkonen's rule

After the wars, Finland became a Nordic welfare state.

At the beginning of 1973, Kekkonen was exceptionally elected president without elections or candidates, which today is considered by some to be the nadir of Finnish democracy and marked the beginning of the final era for Kekkonen.

Integration to the West

In 1982, Mauno Koivisto was elected president, promising to reduce the powers of the president and increase those of the prime minister.

The convergence of Finland and the European Community began in the autumn of 1989 with the decision to join the European Economic Area (EEA).

Following a positive vote in Parliament, Finland's application for EC membership was submitted on 18 March 1992, and membership negotiations began on 1 February 1993 at the same time as with Sweden and Austria.

Finland joined the European Union in 1995. In 2002, the euro replaced the markka as Finland's official currency.

Constitution

The current version of the constitution of Finland was written on 1 March 2000. The first iteration of the constitution was adopted on 17 July 1919. The original comprised four constitutional laws and several amendments, which the latter replaced.[9]

According to the constitution, the legislative powers are exercised by the Parliament, the governmental powers are exercised by the President of the Republic and the Government, and the judicial powers are exercised by government-independent courts of law.[10] The Supreme Court may request legislation that interprets or modifies existing laws. Judges are appointed by the President.[11]

The constitution of Finland and its place in the judicial system are unusual in that there is no constitutional court and the Supreme Court does not have the explicit right to declare a law unconstitutional. In principle, the constitutionality of laws in Finland is verified by a simple vote by Parliament (see parliamentary sovereignty). However, the Parliament's Constitutional Law Committee reviews any doubtful bills and recommends changes, if needed. In practice, the Constitutional Law Committee fulfils the duties of a constitutional court. A Finnish peculiarity is the possibility of making exceptions to the constitution in ordinary laws that are enacted in the same procedure as constitutional amendments. An example of such a law is the State of Preparedness Act, which gives the Government certain exceptional powers in cases of national emergency. As these powers, which correspond to US executive orders, affect constitutional basic rights, the law was enacted in the same manner as a constitutional amendment. However, it can be repealed in the same manner as an ordinary law. In addition to preview by the Constitutional Law Committee, all Finnish courts are obligated to give precedence to the constitution when there is an obvious conflict between the constitution and a regular law. Such a case is, however, very rare.

Some matters are decided by the President of Finland, the Head of State, in plenary meetings with the government, echoing the constitutional history of a privy council. The President is otherwise not present in the government, but decides on issues such as personal appointments and pardons on the advice of the relevant minister. In the ministries, matters of secondary importance are decided by individual ministers, advised by the minister's State Secretary. The Prime Minister and the other ministers in the government are responsible for their actions in office to the Parliament.

Executive branch

Finland has a parliamentary system, even if the President of Finland is formally responsible for foreign policy. Most executive power lies in the cabinet (the Finnish Government) headed by the prime minister. Responsibility for forming the cabinet out of several political parties and negotiating its platform is granted to the leader of the party gaining largest support in the elections for the parliament. This person also becomes prime minister of the cabinet. Any minister and the cabinet as a whole, however, must have continuing trust of the parliament and may be voted out, resign or be replaced. The Government is made up of the prime minister and the ministers for the various departments of the central government as well as an ex officio member, the Chancellor of Justice.

In the official usage, the "cabinet" (valtioneuvosto) are the ministers including the prime minister and the Chancellor of Justice, while the "government" (hallitus) is the cabinet presided by the president. In the popular usage, hallitus (with the president) may also refer to valtioneuvosto (without the president).

President

Though Finland has a primarily parliamentary system, the President has some notable powers. The foreign policy is led by the President in co-operation with the government, and the same applies to matters concerning national security. The main executive power lies in the cabinet, which is headed by the Prime Minister. Before the 2000 constitutional rewrite, the President enjoyed more governing power.

Elected for a six-year term, the president:

- Handles Finland's foreign affairs in cooperation with the Cabinet, except for certain international agreements and decisions of peace or war, which must be submitted to the parliament

- Is Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces;

- Has some decree and appointive powers

- Approves laws, and may call extraordinary parliamentary sessions

- Formally appoints the Prime Minister of Finland selected by the Parliament, and formally appoints the rest of the cabinet (Government) as proposed by the Prime Minister

Government

The Government is made up of the Prime Minister and other ministers for the various ministries of the central government as well as an ex officio member, the Chancellor of Justice. Ministers are not obliged to be members of Parliament and need not be formally identified with any political party.

The Government produces most of the material that the Parliament deals with, such as proposals for new laws or legislative reforms, and the annual budget. The ministers each direct their ministries with relative independence.[12] The current cabinet has 19 ministers in 12 ministries. The number of ministers can be decided by the Government.

The Prime Minister's Office and eleven other ministries make up the Government of Finland.[13]

The head of government is the Prime Minister, currently Petteri Orpo. The Prime Minister designate is subject to election by the Parliament and subsequent appointment by the President of Finland. All the ministers shall be Finnish citizens, known to be honest and competent.[14]

Ministries

The ministries function as administrative and political experts and prepare Government decisions within their mandates. They also represent their relevant administrative sectors in domestic and international cooperation.[15]

New laws are drafted in ministries. There is a tradition of substantial ministerial independence in law drafting. The drafts are then reviewed by government and parliament before enactment. The final legislative power is vested in Parliament, in conjunction with the President of the Republic, according to the Finnish Constitution.[16]

There are 12 ministries in Finland.[17] As the government tends to have more ministers than ministries, some ministries, such as the Ministry of Finance, are associated with multiple ministers.

- Prime Minister's Office

- Ministry for Foreign Affairs

- Ministry of Justice

- Ministry of the Interior

- Ministry of Defence

- Ministry of Finance

- Ministry of Education and Culture

- Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry

- Ministry of Transport and Communications

- Ministry of Employment and the Economy

- Ministry of Social Affairs and Health

- Ministry of the Environment

Parliament

The 200-member unicameral Parliament of Finland (Eduskunta (Finnish), Riksdag (Swedish)) is the supreme legislative authority in Finland. The parliament may alter the Constitution of Finland, bring about the resignation of the Government, and override presidential vetoes. Its acts are not subject to judicial review. Legislation may be initiated by the Government, or one of the members of Parliament, who are elected for a four-year term on the basis of proportional representation through open list multi-member districts. Persons 18 or older, except military personnel on active duty and a few high judicial officials, are eligible for election. The regular parliamentary term is four years; however, the president may dissolve the eduskunta and order new elections at the request of the prime minister and after consulting the speaker of parliament.

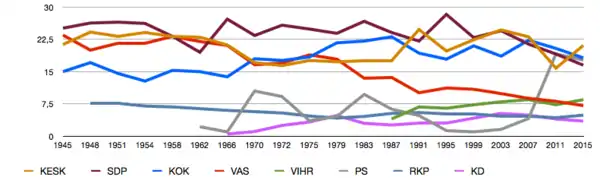

The parliament has, since equal and common suffrage was introduced in 1906, been dominated by secular Conservatives, the Centre Party (former Agrarian Union), and Social Democrats. Nevertheless, none of these has held a single-party majority, with the notable exception of 1916 elections where Social Democrats gained 103 of the 200 seats. After 1944, Communists were a factor to consider for a few decades, and the Finnish People's Democratic League, formed by Communists and others to the left of Social Democrats, was the largest party after 1958 elections. Support for Communists decreased sharply in the early 1980s, while later in the same decade environmentalists formed the Green League, which is now one of the largest parties. The Swedish People's Party represents the Finland-Swedes, especially in language politics. The relative strengths of the parties vary only slightly in the elections due to the proportional election from multi-member districts, but there are some visible long-term trends.

There is no constitutional court; matters concerning constitutional rights or constitutional law are processed by the Constitutional Committee of the Parliament (perustuslakivaliokunta). Additionally, the Constitutional Committee has the sole power to refer a case to the High Court of Impeachment (valtakunnanoikeus) and to authorize police investigations for this purpose.

In addition to the parliament, the Cabinet and President may produce regulations (asetus) through a rulemaking process. These give more specific instructions on how to apply statutes, which often explicitly delegate regulation of specific details to the government. Regulations must be based on existing law, and they can clarify and specify, but not contradict the statute. Furthermore, the rights of an individual must always be based on a statute, not a regulation. Often the statute and the regulation come in similarly named pairs. For example, the law on primary education lists the subjects to be taught, and the regulation specifies the required number of teaching hours. Most of regulations are given by the Cabinet, but the President may give regulations concerning national security. Before 2000, the President had the right to enact regulations on matters not governed by parliamentary law, but this power was removed, and existing regulations were converted into regular statutes by the Parliament.

Political parties and elections

Finland's proportional representation system encourages a multitude of political parties and since about 1980 the trend has been that the same coalition rules for the whole period between elections.

Finland elects on national level a head of state—the president—and a legislature. The president is elected for a six-year term by the people. The Parliament has 200 members, elected for a four-year term by proportional representation in multi-seat constituencies. Finland has a multi-party system, with multiple strong parties, in which no one party often has a chance of gaining power alone, and parties must work with each other to form coalition governments.

In addition to the presidential and parliamentary elections, there are European Parliament elections every five years, and local municipal elections (held simultaneously in every municipality) every four years.

Judiciary

Finland has a civil law system, which is based on Swedish law, with the judiciary exercising limited powers.[20] Proceedings are inquisitorial, where judges preside, conduct finding of fact, adjudication and giving of sanctions such as sentences; no juries are used. In e.g. criminal and family-related proceedings in local courts, the panel of judges may include both lay judges and professional judges, while all appeals courts and administrative courts consist only of professional judges. Precedent is not binding, with the exception of Supreme Court and Supreme Administrative Court decisions.

The judicial system of Finland is divided between courts with regular civil and criminal jurisdiction and administrative courts with responsibility for litigation between the individuals and the administrative organs of the state and the communities. Finnish law is codified and its court system consists of local courts, regional appellate courts, and the Supreme Court. The administrative branch of justice consists of administrative courts and the Supreme Administrative Court.[21] The administrative process has more popularity as it is cheaper and has lower financial risk to the person making claims. In addition to the regular courts, there are a few special courts in certain branches of administration. There is also a High Court of Impeachment for criminal charges (for an offence in office) against the President of the Republic, the justices of the supreme courts, members of the Government, the Chancellor of Justice and the Ombudsman of Parliament.

Although there is no writ of habeas corpus or bail, the maximum period of pre-trial detention has been reduced to four days. For further detention, a court must order the imprisonment. One does not have the right for one phonecall: the police officer leading the investigation may inform relatives or similar if the investigation permits. However, a lawyer can be invited. Search warrants are not strictly needed, and are usually issued by a police officer. Wiretapping does need a court order.

Finland has a civil law (Roman law) system with an inquisitorial procedure. In accordance with the separation of powers, the trias politica principle, courts of law are independent of other administration. They base their decisions solely on the law in force.[22] Criminal cases, civil cases and petitionary matters are dealt in 27 district courts, and then, if the decision is not satisfactory to the involved parties, can be applied in six Courts of Appeal. The Supreme Court of Finland serves as the court of last instance. Appeals against decisions by authorities are considered in six regional administrative courts, with the Supreme Administrative Court of Finland as the court of last instance.[23] The President appoints all professional judges for life. Municipal councils appoint lay judges to district courts.

Administrative divisions

Finland is divided into 313 democratically independent municipalities, which are grouped into 70 sub-regions.[24][25]

As the highest-level division, Finland is divided into 19 counties.[26]

A municipality in Finland can choose to call itself either a "city" or "municipality". A municipality is governed by a municipal council (or a city council) elected by proportional representation once every four years.[27] Democratic decision-making takes place on either the municipal or national level with few exceptions.

Until 2009, the state organization was divided into six provinces. However, the provinces were abolished altogether in 2010. Today, state local presence on mainland Finland is provided by 6 regional state administrative agencies (aluehallintovirasto, avi), and 15 Centres for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment (elinkeino-, liikenne- ja ympäristökeskus, ely-keskus). Regional state administrative agencies have mostly law enforcement, rescue and judicial duties: police, fire and rescue, emergency readiness, basic services, environmental permits and enforcement and occupational health and safety protection. The Centres implement labor and industrial policy, provide employment and immigration services, and promote culture; maintain highways, other transport networks and infrastructure; and protect, monitor and manage the environment, land use and water resources.

Åland is located near the 60th parallel between Sweden and Finland. It enjoys local autonomy by virtue of an international convention of 1921, implemented most recently by the Act on Åland Self-Government of 1951. The islands are further distinguished by the fact that they are entirely Swedish-speaking. Government is vested in the provincial council, which consists of 30 delegates elected directly by Åland's citizens.[28]

Regional and local administration

Finland is divided between six Regional State Administrative Agencies, which are responsible for basic public services and legal permits, such as rescue services and environmental permits.[29] The 15 Centres for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment (ELY Centres) are responsible for the regional implementation and development tasks of the central government.[30]

The basic units for organising government and public services in Finland are the municipalities.[31] As of 2017, there are 311 municipalities, which incorporate the entire country.[32]

Indirect public administration

Indirect public administration supplements and supports the authorities in managing the tasks of the welfare society.[22] It comprises organisations which are not authorities, but which carry out public tasks or execute public powers. Examples of this are issuing hunting licences or carrying out motor vehicle inspection.[33]

Wellbeing services counties

Wellbeing services counties are responsible for organising health, social and emergency services. There are 21 Wellbeing services counties, and the county structure is mainly based on the region structure. Wellbeing services districts are self-governing. They do not have the right to levy taxes. Their funding is based on central government funding. Central government allocates different amounts of funding to the different Wellbeing services counties depending on the structure of their population.[34]

The County Council is the highest decision-making body in the county and is responsible for operations, administration and finance. The delegates and deputy commissioners of the County Council are elected in county elections for a term of four years. The number of delegates varies from 59 to 89. It depends on the population of the county.[34]

Foreign relations

After the second world war, Paasikivi–Kekkonen doctrine was the foreign policy doctrine which aimed at Finland's survival as an independent sovereign, democratic, and capitalist country in the immediate proximity of the Soviet Union. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Finland freed itself from the last restrictions imposed on it by the Paris peace treaties of 1947. The Finnish-Soviet Agreement of Friendship, Co-operation, and Mutual Assistance (and the restrictions included therein) was annulled but Finland recognised the Russian Federation as the successor of the USSR and was quick to draft bilateral treaties of goodwill as well as reallocating Soviet debts.

Finland deepened her participation in the European integration by joining the European Union with Sweden and Austria in 1995. It could be perhaps said that the country's policy of neutrality has been moderated to "military non-alignment" with an emphasis on maintaining a competent independent defence. Peacekeeping under the auspices of the United Nations is the only real extra-national military responsibility which Finland undertakes.

Finland is highly dependent on foreign trade and actively participates in international cooperation. Finland is a member of the European Union, United Nations and World Bank Group and in many of their member organizations.[35]

Finland-Russia relations have been under pressure with annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation, which Finland considers illegal. Together with the rest of the European Union, Finland enforces sanctions against Russia that followed. Still, economic relations have not entirely deteriorated: 11.2% of imports to Finland are from Russia, and 5.7% of exports from Finland are to Russia, and cooperation between Finnish and Russian authorities continues.[36]

After almost 30 years of close partnership with NATO, Finland joined the Alliance on 4 April 2023. Finland's partnership with NATO was historically based on its policy of military non-alignment, which changed following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

See also

References

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Solsten, Eric; Meditz, Sandra W. (1990). Finland: A Country Study. Federal Research Division.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Solsten, Eric; Meditz, Sandra W. (1990). Finland: A Country Study. Federal Research Division.

- "Position and duties - The President of the Republic of Finland: Position and Duties". tpk.fi. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "Role of the Prime Minister". Valtioneuvosto. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "About Parliament". www.eduskunta.fi. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "Duties - The President of the Republic of Finland: Position and Duties: Duties". www.presidentti.fi. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- Finland, Stuart Allt Web Design, Turku. "Finnish Trade Unions: Structure, purpose, and which one to join". www.expat-finland.com. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Democracy Index 2022: Frontline democracy and the battle for Ukraine" (PDF). Economist Intelligence Unit. 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- Solsten, Eric; Meditz, Sandra W. (1990). Finland: a country study. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress.

- "Professori: Lapin sota on unohdettu, seurauksia kantavat lappilaiset". Studio 55. 2015.

- Nousiainen, Jaakko. "The Finnish System of Government: From a Mixed Constitution to Parliamentarism" (PDF). Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- "The Constitution of Finland - unofficial translation" (PDF). Finlex. The Ministry of Justice. 1999–2011.

- "Judicial Appointments Board". Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- Laine, Jarmo (2015). "Parliamentarism in Finland". This Is Finland. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- "Ministries". Suomi.fi. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- "Formation of the Government, Sections 60 and 61" (PDF). Finlex. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- "Ministries". Finnish State Treasury. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- "Law Drafting". Finlex. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- "Ministries". Finnish Government. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- "Suurimpien puolueiden kannatus eduskuntavaaleissa 1945 - 2003 (%)". tilastokeskus.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- "Puolueiden kannatus eduskuntavaaleissa 1991-2015 (%)". stat.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- "450-year-old judicial instructions". oikeus.fi. Ministry of Justice. 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- "Finnish courts". oikeus.fi. Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

-

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "State and municipalities". suomi.fi. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "State and municipalities". suomi.fi. Retrieved 19 January 2017. - "Courts of law". Suomi.fi. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- "Kaupunkien ja kuntien lukumäärä". Kunnat (in Finnish). 1 January 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- "Tilastokeskus - Luokitukset - Sub-regional units 2013 -". www.tilastokeskus.fi.

- "Regions and municipalities". Suomi.fi. 1 January 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- "Kuntalaki 4 §, 15§". Finlex (in Finnish). Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- Silverström, Sören, ed. (2005). "Åland in the European Union" (PDF). Europe Information, Ministry for Foreign A airs of Finland. p. 13.

- "Regional State Administrative Agencies". avi.fi. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- "Centre for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment". ely-keskus.fi. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- "Kuntarakennelaki". Finlex (in Finnish). Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- "Kuntien lukumäärä". vm (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- "Indirect public administration". Suomi.fi. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- "Wellbeing services counties will be responsible for organising health, social and rescue services on 1 January 2023". Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- The World Factbook: Finland (International organization participation) CIA

- "Ulkoasiainministeriö: Maat ja alueet: Kahdenväliset suhteet". Archived from the original on 25 November 2008. Retrieved 9 January 2018.