Geology of Finland

The geology of Finland is made up of a mix of geologically very young and very old materials. Common rock types are orthogneiss, granite, metavolcanics and metasedimentary rocks. On top of these lies a widespread thin layer of unconsolidated deposits formed in connection to the Quaternary ice ages, for example eskers, till and marine clay. The topographic relief is rather subdued because mountain massifs were worn down to a peneplain long ago.

Precambrian shield

The bedrock of Finland belongs to the Fennoscandian Shield[1] and was formed by a succession of orogenies during the Precambrian.[2] The oldest rocks of Finland, those of Archean age, are found in the east and north. These rocks are chiefly granitoids and migmatitic gneiss.[1] Rocks in central and western Finland originated or were emplaced during the Svecokarelian orogeny.[1] Following this last orogeny rapakivi granites intruded various locations of Finland during the Mesoproterozoic and Neoproterozoic, especially in Åland and in the southeast.[1] Jotnian sediments occur usually together with rapakivi granites.[3]

Mountains that existed in Precambrian time were eroded into a level terrain already during the Late Mesoproterozoic.[2][4] With Proterozoic erosion amounting to tens of kilometers,[5] many of the Precambrian rocks seen today in Finland are the "roots" of ancient massifs.[2]

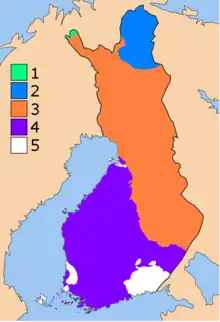

As Finland is in the older part of the Fennoscandian Shield, its basement rocks are within three of the shield's older subdivisions known as domains: the Kola, Karelian and Svecofennian domains. This subdivision, established by Gaál and Gorbachev in 1987, is based on the different geological histories of the domains prior to their final amalgamation 1,800 million years ago.[6]

Kola Domain

The extreme northeast of Finland is part of the Kola Domain because it shows considerable affinity with the geology of the Kola Peninsula in Russia. Around Lake Inari there are paragneiss, orthogneiss and greenstone belts. Rocks in this part of Finland are of Archean and Proterozoic age.[7]

To the south and west of Lake Inari lies an elongate and arcuate zone of granulite rock known as the Lapland Granulite Belt. The belt is up to 80 km wide. The main rocks of the belt are migmatized greywacke and argillites. Studies of detrital zircon show that the sedimentary protolith of the metamorphic rocks of the belt could not be more than 2900–1940 million years old.[8] The belt has norite and enderbite intrusions of calc-alkaline chemistry.[9]

Karelian Domain

The Karelian Domain, or Karelian Block, makes up most of the bedrock of the northeastern part of Finland[10] extending into nearby areas of Russia.[6] The Karelian domain is made up of a collage of rock formed during Archean and Paleoproterozoic times.[10][7] The boundary to the Kola Domain is made up of a gently dipping décollement where the Lapland Granulite Belt has been thrust southward over rocks of the Karelian Domain.[11]

Archean rocks in the Karelian Domain are north-south medium grade greenstone and metasedimentary belts. The belts are intruded by granitoids, usually monzogranite and granodiorite. Besides these belts and intrusions there is also metasedimentary gneiss formed at intermediate pressures.[6] Along the central part of the Finland–Russia border lies the Belomorian terrane, a subunit of the Karelian Domain thought to have formed by a collision between the Kola Domain with the Karelian Domain in the Paleoproterozoic.[6][11] This collision marked the final merger of both crustal blocks.[12] Rocks of the Belomorian terrane, like the granitoid gneisses common there, are of high grade.[11]

The Central Lapland granitoid complex covers up much of the interior of northern Finland. These rocks were formed in the final stages of the Svecofennian orogeny and are mostly made up of coarse-grained granites.[13] An alignment of granitoid intrusions southeast of Oulu likely shares the same origin.[14]

Finland's three ophiolites crop out within the Karelian Domain. These are the Jormua, Outokumpu and Nuttio ophiolite complexes.[15] All of them were emplaced in Paleoproterozoic times.[16] The Jormua and Outokumpu ophiolites lie parallel to and near the boundary with the Svecofennian Domain.[15] Also towards the border with the Svecovefennian Domain there is a series of metamorphosed Archean rocks that are stacked into an imbrication pattern.[11]

Svecofennian Domain

The southwestern part of Finland is mainly made up of rocks of the Svecofennian Domain or Svecofennian orogen.[10] These rocks are invariably of Proterozoic age. Its boundary with the Karelian Domain (of mixed Archean and Paleoproterozoic rocks) is a northwest-southeast diagonal.[10] Plutonic rocks that formed during accretion of volcanic arcs or continental collisions of the Svecofennian orogeny are common in Svecofennian Domain.[17][18] Among these rocks the largest grouping is the Central Finland granitoid complex covering up much of Central Finland, Southern Ostrobothnia and Pirkanmaa.[18] Granitoids that intruded in the aftermath of the Svercofennian orogeny are common in southern Finland occurring mostly within ca. 100 km of the Gulf of Finland or Lake Ladoga.[18][19] These so-called Lateorogenic granites are distinguished by usually containing garnet and cordierite and being accompanied by rather few rocks of mafic and intermediate composition.[19] Scattered small granitoids crop out within the same zone. Formed 1810–1770 million years ago, these are the youngest granitoids in southern Finland associated with the Svecofennian orogeny.[14]

Rapakivi granite and Jotnian sediment

Jotnian sediments are the oldest known sediments in the Baltic area that have not been subject to significant metamorphism.[20][21] These sediments are typically quartz-rich sandstones, siltstones, arkose, shale and conglomerates.[22][20] The characteristic red colour of Jotnian sediments is due to their deposition in subaerial (e.g. non-marine) conditions.[21] In Finland, Jotnian sediments occur in the Muhos Graben near Oulu at the northeastern end of the Gulf of Bothnia[23][21] and further south near the coast at Satakunta.[23][24] Jotnian rocks are also found offshore between Finland and Sweden in the Gulf of Bothnia and the Åland Sea including South Kvarken.[23][25][26] Known Jotnian rocks at the Åland Sea are sandstones belonging to the informally defined Söderarm Formation. Above these there are Upper Riphean and Vendian sandstones and shales.[27] There is evidence suggesting that Jotnian rocks, or even a Jotnian platform, once covered much of Fennoscandia and were not restricted to a few localities like today.[26][28] The limited geographical extent of Jotnian sediments at present is indebted to their erosion over geological time.[26] Sedimentary rocks as old as the Jotnian sediments have a low preservation potential.[29]

The distribution of some Jotnian sediments is spatially associated with the occurrence of rapakivi granite.[22] Korja and co-workers (1993) claim the Jotnian sediment–rapakivi granite coincidence at the Gulf of Finland and the Gulf of Bothnia is related to the existence of thin crust at these locations.[3]

Alkaline rocks

Small outcrops of alkaline rocks, carbonatites and kimberlites exist in Finland[30] including the western and southernmost outcrops of the Permian-aged Kola Alkaline Province.[31][30] The Kola Alkaline Province is commonly presumed to represent an igneous hotspot created by a mantle plume.[32] Carbonatites in Finland have wide range in ages but they all derive from a "well-mixed" portion of the upper mantle. The Siilinjärvi carbonatite complex of Archean age is one of the Earth's oldest carbonatites.[30] All known kimberlites are concentrated near the towns of Kuopio and Kaavi. These are grouped in two clusters and include diatremes and dykes.[33]

Caledonian rocks

The youngest rocks in Finland are those found near Kilpisjärvi in Enontekiö (the northwesternmost part of the country's northwestern arm).[35] These rocks belong to the Scandinavian Caledonides that assembled in Paleozoic times.[2] During the Caledonian orogeny Finland was likely a sunken foreland basin covered by sediments; subsequent uplift and erosion would have eroded all of these sediments.[36] In Finland, Caledonian nappes overlie shield rocks of Archean age.[7] Despite occurring in about the same area the Scandinavian Caledonides and the modern Scandinavian Mountains are unrelated.[37][38]

Quaternary deposits

The ice sheet that covered Finland intermittently during the Quaternary grew out from the Scandinavian Mountains.[39][upper-alpha 1] By some estimates the Quaternary glaciers eroded away on average 25 m of rock in Finland,[2] with the degree of erosion being highly variable.[5] Some of the material eroded in Finland has ended up in Germany, Poland, Russia and the Baltic states.[2] Ground till left by the Quaternary ice sheets is ubiquitous in Finland.[2] Relative to the rest of Finland, the southern coastal areas have a thin and patchy cover of till evidencing a more prominent role of glacial erosion in the area, whereas Ostrobothnia and parts of Lapland stand out for their thick till cover.[40][upper-alpha 2] The central parts of the Weichsel ice sheet had cold-based conditions during the times of maximum extent. Therefore, pre-existing landforms and deposits in northern Finland escaped glacial erosion and are now particularly well preserved.[42] Northwest to southeast movement of the ice has left a field of aligned drumlins in central Lapland. Ribbed moraines found in the same area reflect a later west to east change in movement of the ice.[42]

During the last deglaciation, the first part of Finland to become ice-free was the southeastern coast; this occurred shortly before the Younger Dryas cold-spell 12,700 years before present (BP). While the ice cover continued to retreat in the southeast after Younger Dryas, retreat also occurred in the east and northeast. The retreat was fastest from the southeast resulting in the lower course of the Tornio river in northwest Finland becoming the last part of the country to be ice-free. Finally, by 10,100 years BP, the ice cover had all but left Finland, retreating to Sweden and Norway before fading away.[43] Ice retreat was accompanied by the formation of eskers and the dispersal of fine-grained sediment deposited as varves.[2]

As the ice sheet became thinner and retreated, the land began to rise due to post-glacial rebound. Much of Finland was under water when the ice retreated and was gradually uplifted in a process that continues today.[44][upper-alpha 3] Not all areas were drowned at the same time and it is estimated that, at one time or another, about 62% has been under water.[45] The maximum height of the ancient shoreline varied from region to region: in southern Finland 150 to 160 m, in central Finland about 200 m and in eastern Finland up to 220 m.[44] Once free of ice and water, soils have developed in Finland. Podzols with till as parent material now cover about 60% of Finland's land area.[46]

| Material | Land surface % | Cultivated soil % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Till | 53 | 16 | |

| Peat thicker than 30 cm | 15 | 18 | |

| Bare rock | 13 | - | |

| Marine and lacustrine silt and clay | 8 | 66 | |

| Eskers and glacifluvial material | 5 | ||

Economic geology

Mining for metals in Finland began in 1530 at the Ojamo iron mine[47][upper-alpha 4] but mining in the country was minimal until the 1930s.[48] The Outokumpu ore deposit, discovered in 1910, was key to the development of mining in Finland during the 20th century. When Outokumpu opened in 1910 it was Finland's first sulphide ore to be mined. This mine closed in 1989.[47] Another important Finnish mining resource was the nickel of Petsamo, which was mined by Canadian INCO from the 1920s onwards. Petsamo and its mines were, however, lost to the Soviet Union in 1944 as result of the Moscow Armistice.[48]

From 2001 to 2004 the number of metallic ores being mined dropped from eleven to the following four:[48]

- Pyhäsalmi zinc mine, Immet Mining Corporations (Canadian financed)

- Nivala nickel mine, Outokumpu

- Keminmaa chromium mine, Avesta Polarit

- Sodankylä gold mine, ScanMining (Swedish financed)

There are some uranium resources in Finland, but to date no commercially viable deposits have been identified for exclusive mining of uranium.[49] In the Karelian Domain, there are various layered mafic intrusions of early Paleoproterozoic age that have been exploited for vanadium.[50]

Most of Finland's metallic ores formed in the Paleoproterozoic during the Svecofennian orogeny or during the period of complex extensional tectonics that preceded it.[51]

Non-metallic resources

Non-metallic resources Finland include phosphorus that has been mined at the Siilinjärvi carbonatite since 1979, the outcrop being originally discovered in 1950.[30] The bedrock of Finland contain various types of gemstones.[48] The Lahtojoki kimberlite has gem quality garnet and diamond xenocrysts.[52]

Finland has a thriving quarrying industry. Finnish dimension stone has been used historically for buildings in Helsinki and imperial Russia's Saint Petersburg and Reval. Today, the main importers of Finnish stone are China, Germany, Italy and Sweden. The dimension stone quarried in Finland includes granites, such as the wiborgite variety of rapakivi granite, and marble. Soapstone from Finland's schist zone is also quarried for use in ovens.[53]

See also

Notes

- Perhaps the best modern analogues to this early glaciation are the ice fields of Andean Patagonia.[39]

- Among the glacial deposits of Finnish Lapland pre-Quaternary Cenozoic marine microfossils have been found. These findings were first reported by Astrid Cleve in 1934, leading to the assumption that the areas was drowned by the sea during the Eocene. However, as of 2013, no sedimentary deposit from this time has been found and the marine fossils may have arrived much later by wind transport.[41]

- It is predicted that ongoing post-glacial rebound will result in the splitting of the Gulf of Bothnia into a southern gulf and a northern lake across the Norra Kvarken area no earlier than in 2,000 years.[45]

- Mining in Finland developed later than in Sweden proper where mining had been going on since the High Middle Ages but earlier than in Russian Karelia where mining began in the 18th century.[47]

References

- Behrens, Sven; Lundqvist, Thomas. "Finland: Terrängformer och berggrund". Nationalencyklopedin (in Swedish). Cydonia Development. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- Lindberg, Johan (April 4, 2016). "berggrund och ytformer". Uppslagsverket Finland (in Swedish). Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- Korja, A.; Korja, T.; Luosto, U.; Heikkinen, P. (1993). "Seismic and geoelectric evidence for collisional and extensional events in the Fennoscandian Shield – implications for Precambrian crustal evolution". Tectonophysics. 219 (1–3): 129–152. Bibcode:1993Tectp.219..129K. doi:10.1016/0040-1951(93)90292-r.

- Lundmark, Anders Mattias; Lamminen, Jarkko (2016). "The provenance and setting of the Mesoproterozoic Dala Sandstone, western Sweden, and paleogeographic implications for southwestern Fennoscandia". Precambrian Research. 275: 197–208. Bibcode:2016PreR..275..197L. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2016.01.003.

- Lidmar-Bergström, Karna (1997). "A long-term perspective on glacial erosion". Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 22 (3): 297–306. Bibcode:1997ESPL...22..297L. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9837(199703)22:3<297::AID-ESP758>3.0.CO;2-R.

- Sorjonen-Ward & Luukkonen 2005, pp. 22–23.

- Vaasjoki et al. 2005, pp. 6–7.

- Lundqvist, Jan; Lundqvist, Thomas; Lindström, Maurits; Calner, Mikael; Sivhed, Ulf (2011). "Svekokarelska Provinsen". Sveriges Geologi: Från urtid till nutid (in Swedish) (3rd ed.). Spain: Studentlitteratur. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-91-44-05847-4.

- Lahtinen, Raimo; Korja, Annakaisa; Nironen, Mikko; Heikkinen, Pekka (2009). "Palaeoproterozoic accretionary processes in Fennoscandia". In Cawood, P.A.; Kröner, A. (eds.). Earth Accretionary Systems in Space and Time. Vol. 318. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. pp. 237–256.

- Vaasjoki et al. 2005, pp. 4–5.

- Sorjonen-Ward & Luukkonen 2005, pp. 24–25.

- Sorjonen-Ward & Luukkonen 2005, pp. 70–71.

- Nironen 2005, pp. 457–458.

- Nironen 2005, pp. 459–460.

- Peltonen 2005, pp. 239–240.

- Peltonen 2005, pp. 241–242.

- Nironen 2005, pp. 445–446.

- Nironen 2005, pp. 447–448.

- Nironen 2005, pp. 455–456.

- Usaityte, Daiva (2000). "The geology of the southeastern Baltic Sea: a review". Earth-Science Reviews. 50 (3): 137–225. Bibcode:2000ESRv...50..137U. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(00)00002-7.

- Simonen, Ahti (1980). "The Precambrian in Finland". Geological Survey of Finland Bulletin. 304.

- Kohonen & Rämö 2005, p. 567.

- Amantov, A.; Laitakari, I.; Poroshin, Ye (1996). "Jotnian and Postjotnian: Sandstones and diabases in the surroundings of the Gulf of Finland". Geological Survey of Finland, Special Paper. 21: 99–113. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- Paulamäki, Seppo; Paananen, Markku; Elo, Seppo (2004). "Structure and geological evolution of the bedrock of southern Satakunta SW Finland" (PDF). Working Report. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- Nagornji, M.A.; Nikolaev, V.G. (2005). "The quasiplatform sediments of the East European Platform". Russian Journal of Earth Sciences. 7 (5): 1–12. doi:10.2205/2005ES000171.

- Paulamäki, Seppo; Kuivamäki, Aimo (2006). "Depositional History and Tectonic Regimes within and in the Margins of the Fennoscandian Shield During the Last 1300 Million Years" (PDF). Working Report. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- Amantov, Alexey; Hagenfeldt, Stefan; Söderberg, Per (1995). "The Mesoproterozoic to Lower Palaeozoic sedimentary bedrock sequence in the northern Baltic Proper, Åland Sea, Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga". Proceedings of the Third Marine Geological Conference "The Baltic". pp. 19–25.

- Rodhe, Agnes (1988). "The dolerite breccia of Tärnö, Late Proterozoic of southern Sweden". Geologiska Föreningen i Stockholm Förhandlingar. 110 (2): 131–142. doi:10.1080/11035898809452652.

- Rodhe, Agnes (1986). "Geochemistry and clay mineralogy of argillites in the Late Proterozoic Almesikra group, south Sweden". Geologiska Föreningen i Stockholm Förhandlingar. 107 (3): 175–182. doi:10.1080/11035898809452652. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- O'Brien et al. 2005, pp. 607–608.

- Downes, Hilary; Balaganskaya, Elena; Beard, Andrew; Liferovich, Ruslan; Demaiffe, Daniel (2005). "Petrogenetic processes in the ultramafic, alkaline and carbonatitic magmatism in the Kola Alkaline Province: a review" (PDF). Lithos. 85 (1–4): 48–75. Bibcode:2005Litho..85...48D. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2005.03.020.

- Lundqvist, Jan; Lundqvist, Thomas; Lindström, Maurits; Calner, Mikael; Sivhed, Ulf (2011). "Svekokarelska Provinsen". Sveriges Geologi: Från urtid till nutid (in Swedish) (3rd ed.). Spain: Studentlitteratur. p. 253. ISBN 978-91-44-05847-4.

- O'Brien, Hugh E.; Tyni, Matti (1999). "Mineralogy and Geochemistry of Kimberlites and Related Rocks from Finland". Proceedings of the 7th International Kimberlite Conference. pp. 625–636.

- Tikkanen, M. (2002). "The changing landforms of Finland". Fennia. 180 (1–2): 21–30.

- Puustinen, K., Saltikoff, B. and Tontti, M. (2000) Metallic Mineral Deposits Map of Finland, 1:1 million, Espoo, Geological Survey of Finland

- Murrell, G.R.; Andriessen, P.A.M. (2004). "Unravelling a long-term multi-event thermal record in the cratonic interior of southern Finland through apatite fission track thermochronology". Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C. 29 (10): 695–706. Bibcode:2004PCE....29..695M. doi:10.1016/j.pce.2004.03.007.

- Green, Paul F.; Lidmar-Bergström, Karna; Japsen, Peter; Bonow, Johan M.; Chalmers, James A. (2013). "Stratigraphic landscape analysis, thermochronology and the episodic development of elevated, passive continental margins". Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland Bulletin. 30: 18. doi:10.34194/geusb.v30.4673.

- Schiffer, Christian; Balling, Neils; Ebbing, Jörg; Holm Jacobsen, Bo; Nielsen, Søren Bom (2016). "Geophysical-petrological modelling of the East Greenland Caledonides – Isostatic support from crust and upper mantle". Tectonophysics. 692: 44–57. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2016.06.023.

- Fredin, Ola (2002). "Glacial inception and Quaternary mountain glaciations in Fennoscandia". Quaternary International. 95–96: 99–112. Bibcode:2002QuInt..95...99F. doi:10.1016/s1040-6182(02)00031-9.

- Kleman, J.; Stroeven, A.P.; Lundqvist, Jan (2008). "Patterns of Quaternary ice sheet erosion and deposition in Fennoscandia and a theoretical framework for explanation". Geomorphology. 97 (1–2): 73–90. Bibcode:2008Geomo..97...73K. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2007.02.049.

- Hall, Adrian M.; Ebert, Karin (2013). "Cenozoic microfossils in northern Finland: Local reworking or distant wind transport?". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 388: 1–14. Bibcode:2013PPP...388....1H. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2013.07.012.

- Sarala, Pertti (2005). "Weichselian stratigraphy, geomorphology and glacial dynamics in southern Finnish Lapland". Bulletin of the Geological Society of Finland. 77 (2): 71–104. doi:10.17741/bgsf/77.2.001.

- Stroeven, Arjen P.; Hättestrand, Clas; Kleman, Johan; Heyman, Jakob; Fabel, Derek; Fredin, Ola; Goodfellow, Bradley W.; Harbor, Jonathan M.; Jansen, John D.; Olsen, Lars; Caffee, Marc W.; Fink, David; Lundqvist, Jan; Rosqvist, Gunhild C.; Strömberg, Bo; Jansson, Krister N. (2016). "Deglaciation of Fennoscandia". Quaternary Science Reviews. 147: 91–121. Bibcode:2016QSRv..147...91S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.09.016.

- Lindberg, Johan (May 2, 2011). "landhöjning". Uppslagsverket Finland (in Swedish). Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- Tikkanen, Matti; Oksanen, Juha (2002). "Late Weichselian and Holocene shore displacement history of the Baltic Sea in Finland". Fennia. 180 (1–2). Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- Tilberg, Ebba, ed. (1998). Nordic Reference Soils. Nordic Council of Ministers. p. 16.

- Eilu, P.; Boyd, R.; Hallberg, A.; Korsakova, M.; Krasotkin, S.; Nurmi, P.A.; Ripa, M.; Stromov, V.; Tontti, M. (2012). "Mining history of Fennoscandia". In Eilu, Pasi (ed.). Mineral deposits and metallogeny of Fennoscandia. Geological Survey of Finland, Special Paper. Vol. 53. Espoo. pp. 19–32. ISBN 978-952-217-175-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lindberg, Johan (June 17, 2009). "Gruvindustri". Uppslagsverket Finland (in Swedish). Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- "Uraanikaivokset". Gtk.fi. Archived from the original on 2015-03-18. Retrieved 2015-04-26.

- Iljina & Hanski 2005, p. 103.

- Eilu, P.; Ahtola, T.; Äikäs, O.; Halkoaho, T.; Heikura, P.; Hulkki, H.; Iljina, M.; Juopperi, H.; Karinen, T.; Kärkkäinen, N.; Konnunaho, J.; Kontinen, A.; Kontoniemi, O.; Korkiakoski, E.; Korsakova, M.; Kuivasaari, T.; Kyläkoski, M.; Makkonen, H.; Niiranen, T.; Nikander, J.; Nykänen, V.; Perdahl, J.-A.; Pohjolainen, E.; Räsänen, J.; Sorjonen-Ward, P.; Tiainen, M.; Tontti, M.; Torppa, A.; Västi, K. (2012). "Metallogenic areas in Finland". In Eilu, Pasi (ed.). Mineral deposits and metallogeny of Fennoscandia. Geological Survey of Finland, Special Paper. Vol. 53. Espoo. pp. 19–32. ISBN 978-952-217-175-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - O'Brien et al. 2005, pp. 637–638.

- Backman, Sigbritt (June 28, 2010). "Stenindustri". Uppslagsverket Finland (in Swedish). Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- Bibliography

- Lehtinen, Martti; Nurmi, Pekka A., eds. (2005). Precambrian Geology of Finland. Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-08-045759-8.

- Iljina, M.; Hanski, E. "Layered Mafic Intrusions of the Tornio-Näränkävaara Belt". pp. 100–137

- Kohonen, J.; Rämö, O.T. "Sedimentary Rocks, Diabases, and Late Cratonic Evolution". pp. 563–603.

- Nironen, M. "Proterozoic Orogenic Granitoid Rocks". pp. 442–479.

- O'Brien, H.E.; Peltonen, P.; Vartiainen, H. "Kimberlites, Carbonantites, and Alkaline Rocks". pp. 237–277.

- Peltonen, P. "Ophiolites". pp. 237–277.

- Sorjonen-Ward, P.; Luukkonen, E.J. "Archean Rocks". pp. 18–99.

- Vaasjoki, M.; Korsman, K.; Koistinen, T. "Overview". pp. 1–17.