Drumlin

A drumlin, from the Irish word droimnín ("little ridge"), first recorded in 1833, in the classical sense is an elongated hill in the shape of an inverted spoon or half-buried egg[1][2] formed by glacial ice acting on underlying unconsolidated till or ground moraine. Assemblages of drumlins are referred to as fields or swarms;[3][4] they can create a landscape which is often described as having a 'basket of eggs topography'.[5]

The low ground between two drumlins is known as a dungeon; dungeons have colder microclimates in winter from settling cold air.

Morphology

Drumlins occur in various shapes and sizes,[6] including symmetrical (about the long axis), spindle, parabolic forms, and transverse asymmetrical forms. Generally, they are elongated, oval-shaped hills, with a long axis parallel to the orientation of ice flow and with an up-ice (stoss) face that is generally steeper than the down-ice (lee) face.[7]

Drumlins are typically between 250 and 1,000 m (820 and 3,280 ft) long and between 120 and 300 m (390 and 980 ft) wide.[8] Drumlins generally have a length:width ratio of between 1.7 and 4.1[8] and it has been suggested that this ratio can indicate the velocity of the glacier. That is, since ice flows in laminar flow, the resistance to flow is frictional and depends on area of contact; thus, a more elongated drumlin would indicate a lower velocity and a shorter one would indicate a higher velocity.[9]

Occurrence

Drumlins and drumlin swarms are glacial landforms composed primarily of glacial till. They form near the margin of glacial systems, and within zones of fast flow deep within ice sheets, and are commonly found with other major glacially-formed features (including tunnel valleys, eskers, scours, and exposed bedrock erosion).[10]

Drumlins are often encountered in drumlin fields of similarly shaped, sized and oriented hills. Many Pleistocene drumlin fields are observed to occur in a fan-like distribution.[11] The long axis of each drumlin is parallel to the direction of movement of the glacier at the time of formation.[12] Inspection of aerial photos of these fields reveals glacier's progress through the landscape. The Múlajökull drumlins of Hofsjökull are also arrayed in a splayed fan distribution around an arc of 180°.[13] This field surrounds the current lobe of the glacier and provide a view into the past, showing the previous extent and motion of the ice.

Composition

Drumlins may comprise layers of clay, silt, sand, gravel and boulders in various proportions; perhaps indicating that material was repeatedly added to a core, which may be of rock or glacial till. Alternatively, drumlins may be residual, with the landforms resulting from erosion of material between the landforms. The dilatancy of glacial till was invoked as a major factor in drumlin formation.[14] In other cases, drumlin fields include drumlins made up entirely of hard bedrock (e.g. granite or well-lithified limestone).[15] These drumlins cannot be explained by the addition of soft sediment to a core. Thus, accretion and erosion of soft sediment by processes of subglacial deformation do not present unifying theories for all drumlins—some are composed of residual bedrock.

Formation

There are two main theories of drumlin formation.[16] The first, constructional, suggests that they form as sediment is deposited from subglacial waterways laden with till including gravel, clay, silt, and sand. As the drumlin forms, the scrape and flow of the glacier continues around it and the material deposited accumulates, the clasts[17] align themselves with direction of flow.[18] It is because of this process that geologists are able to determine how the drumlin formed using till fabric analysis, the study of the orientation and dip of particles within a till matrix.[19] By examining the till particles and plotting their orientation and dip on a stereonet, scientists are able to see if there is a correlation between each clast and the overall orientation of the drumlin: the more similar in orientation and dip of the clasts throughout the drumlin, the more likely it is that they had been deposited during the formation process. If the opposite is true, and there doesn't seem to be a link between the drumlin and the till, it suggests that the other main theory of formation could be true.

The second theory proposes that drumlins form by erosion of material from an unconsolidated bed. Erosion under a glacier in the immediate vicinity of a drumlin can be on the order of a meter's depth of sediment per year, depending heavily on the shear stress acting on the ground below the glacier from the weight of the glacier itself, with the eroded sediment forming a drumlin as it is repositioned and deposited.[8]

A hypothesis that catastrophic sub-glacial floods form drumlins by deposition or erosion challenges conventional explanations for drumlins.[20] It includes deposition of glaciofluvial sediment in cavities scoured into a glacier bed by subglacial meltwater, and remnant ridges left behind by erosion of soft sediment or hard rock by turbulent meltwater. This hypothesis requires huge, subglacial meltwater floods, each of which would raise sea level by tens of centimeters in a few weeks. Studies of erosional forms in bedrock at French River, Ontario, Canada, provide evidence for such floods.

The recent retreat of a marginal outlet glacier of Hofsjökull in Iceland[21] exposed a drumlin field with more than 50 drumlins ranging from 90 to 320 m (300–1,050 ft) in length, 30 to 105 m (100–340 ft) in width, and 5 to 10 m (16–33 ft) in height. These formed through a progression of subglacial depositional and erosional processes, with each horizontal till bed within the drumlin created by an individual surge of the glacier.[13] The above theory for the formation of these Icelandic drumlins best explains one type of drumlin. However, it does not provide a unifying explanation of all drumlins. For example, drumlin fields including drumlins composed entirely of hard bedrock cannot be explained by deposition and erosion of unconsolidated beds.[15] Furthermore, hairpin scours around many drumlins are best explained by the erosive action of horseshoe vortices around obstacles in a turbulent boundary layer.[22][23]

Soil development on drumlins

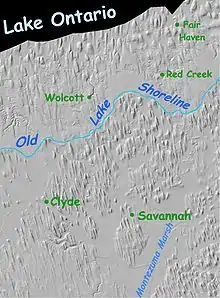

Recently formed drumlins often incorporate a thin "A" soil horizon (often referred to as "'topsoil'" which accumulated after formation) and a thin "Bw" horizon (commonly referred to as "'subsoil'"). The "C" horizon, which shows little evidence of being affected by soil forming processes (weathering), is close to the surface, and may be at the surface on an eroded drumlin. Below the C horizon the drumlin consists of multiple beds of till deposited by lodgment and bed deformation. On drumlins with longer exposure (e.g. in the Lake Ontario drumlin field in New York State) soil development is more advanced, for example with the formation of clay-enriched "Bt" horizons.[13]

Examples of drumlins

Europe

Besides the Icelandic drumlins mentioned above, the literature also documents extensive drumlin fields in England, Scotland and Wales,[8] Switzerland,[24] Poland, Estonia (Vooremaa), Latvia, Sweden, around Lake Constance north of the Alps, in the Republic of Ireland (County Leitrim, County Monaghan, County Mayo and County Cavan), in Northern Ireland (County Fermanagh, County Armagh, and in particular County Down), Germany, Hindsholm in Denmark, Finland and Greenland.[25][8]

North America

The majority of drumlins observed in North America were formed during the Wisconsin glaciation.

The largest drumlin fields in the world formed beneath the Laurentide Ice Sheet and are found in Canada — Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, northern Saskatchewan, northern Manitoba, northern Ontario and northern Quebec.[26] Drumlins occur in every Canadian province and territory. Clusters of thousands of drumlins are found in:[27]

- Southern Ontario (along eastern end of Oak Ridges Moraine near Peterborough, as well as areas to the west near Dundas and Guelph[28])

- Central-Eastern Ontario (Douro-Dummer)

- Ontario – most of Northumberland County (between Rice Lake and Trenton, including Trent Hills)

- The Thelon Plan of the Northwest Territories

- Alberta – drumlins are located on the Morley Flats in the Stony Indian Reserve west of Calgary, as well as south of the Ghost Reservoir.[29]

- Saskatchewan – 80 km (50 mi) south of the east end of Lake Athabasca[29]

- Southwest of Amundsen Gulf in Nunavut

- West Lawrencetown, Nova Scotia.

In the United States, drumlins are common in:

- Central New York (between the south shore of Lake Ontario and Cayuga Lake)[30][31]

- The lower Connecticut River valley

- Long Island[32][33]

- Manhattan[33]

- Eastern Massachusetts

- Eastern Connecticut in Windham and New London Counties

- The Monadnock Region of New Hampshire

- Michigan (central and southern Lower Peninsula)[34]

- Minnesota[35][8]

- The Puget Sound region of Washington state[36]

- Wisconsin

Asia

Drumlins are found at Tiksi, Sakha Republic, Russia.[8]

South America

Extensive drumlin fields are found in Patagonia.[8] A major drumlin field extends on both sides of the Strait of Magellan covering the surroundings of Punta Arenas' Carlos Ibáñez del Campo Airport, Isabel Island and an area south of Gente Grande Bay in Tierra del Fuego Island.[37]

Land areas around Beagle Channel host also drumlin fields; for example Gable Island and northern Navarino Island.

Antarctica

In 2007, drumlins were observed to be forming beneath the ice of a West Antarctic ice stream.[38]

See also

- Crag and tail – Geographic feature created by glaciation, a similar formation, with a more resilient core (generally composed of igneous or metamorphic rock)

- Glacial landform – Landform created by the action of glaciers

- Landform – Feature of the solid surface of a planetary body

- Lincoln Hills – hill range in Missouri

- Mima mounds

- Ribbed moraines – Landform of ridges deposited by a glacier or ice sheet transverse to ice flow

- Roche moutonnée – Rock formation created by the passing of a glacier

- Sediment – Particulate solid matter that is deposited on the surface of land

References

- Menzies(1979) quoted in Benn, D.I. & Evans, D.J.A. 2003 Glaciers & Glaciation, Arnold, London (p431) ISBN 0-340-58431-9

- Bryce, James (1838). "On the evidences of diluvial action in the north of Ireland". Journal of the Geological Society of Dublin. 1: 34–44. Archived from the original on 2021-06-03. Retrieved 2021-06-03. Originally presented in 1833 by Irish geologist James Bryce (1806–1877). From p. 37: "This peculiar form is so striking that the peasantry have appropriated an expressive name to such ridges; while Knock, Sleive, Ben, have each their peculiar significations, the names Drum and Drumlin (Dorsum) have been applied to such hills as we have been describing."

- Benn, Douglas I.; Evans, David J.A. (2003). Glaciers and Glaciation (First ed.). London: Arnold. p. 434. ISBN 0340584319.

- "Glacial Landforms". Bitesize. BBC. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- "Cavan" (PDF). Geoschol – Geology for schools in Ireland. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-11-22.

- Spagnolo, Matteo; Clark, Chris D.; Hughes, Anna L.C.; Dunlop, Paul; Stokes, Chris R. (2010). "The planar shape of drumlins". Sedimentary Geology. 232 (3–4): 119–129. Bibcode:2010SedG..232..119S. doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2010.01.008.

- Menzies (1979). "A review of the literature on the formation and location of drumlins". Earth-Science Reviews. 14 (4): 315–359. Bibcode:1979ESRv...14..315M. doi:10.1016/0012-8252(79)90093-X.

- Clark, Chris D.; Hughes, Anna L.C.; Greenwood, Sarah L.; Spagnolo, Matteo; Ng, Felix S.L. (April 2009). "Size and shape characteristics of drumlins, derived from a large sample, and associated scaling laws" (PDF). Quaternary Science Reviews. 28 (7–8): 677–692. Bibcode:2009QSRv...28..677C. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2008.08.035.

- Nye, J (1952). "The Mechanics of Glacier Flow". Journal of Glaciology. 2 (12): 82. Bibcode:1952JGlac...2...82N. doi:10.1017/S0022143000033967.

- Shaw, J.; Kvill, D. (1984). "A glaciofluvial origin for drumlins of the Livingstone Lake area, Saskatchewan". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 21 (12): 1442–1459. Bibcode:1984CaJES..21.1442S. doi:10.1139/e84-150.

- Patterson, C.J.; Hooke, R.L. (1995). "Physical environment of drumlin formation". Journal of Glaciology. 41 (137): 30–38. Bibcode:1995JGlac..41...30P. doi:10.1017/S0022143000017731.

- Spagnolo, M.; Clark, C.D.; Hughes, A.L.C.; Dunlop, P.; Stokes, C.R. (2010). "The planar shape of drumlins". Sedimentary Geology. 232 (3–4): 119–129. Bibcode:2010SedG..232..119S. doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2010.01.008.

- Johnson, M. D.; Schomacker, A.; Benediktsson, I. O.; Geiger, A. J.; Ferguson, A.; Ingolfsson, O. (2010). "Active drumlin field revealed at the margin of Mulajokull, Iceland: A surge-type glacier". Geology. 38 (10): 943–946. Bibcode:2010Geo....38..943J. doi:10.1130/G31371.1.

- Smalley, Ian J.; Unwin, David J. (1968). "The Formation and Shape of Drumlins and their Distribution and Orientation in Drumlin Fields". Journal of Glaciology. 7 (51): 377–390. doi:10.3189/S0022143000020591. S2CID 129285660.

- Lesemann, Jerome-Etienne; Brennand, Tracy A. (November 2009). "Regional reconstruction of subglacial hydrology and glaciodynamic behaviour along the southern margin of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet in British Columbia, Canada and northern Washington State, USA". Quaternary Science Reviews. 28 (23–24): 2420–2444. Bibcode:2009QSRv...28.2420L. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.04.019.

- Yu, Peter; Eyles, Nick; Sookhan, Shane (2015). "Automated drumlin shape and volume estimation using high resolution LiDAR imagery (Curvature Based Relief Separation): A test from the Wadena Drumlin Field, Minnesota". Geomorphology. 246: 589–601. Bibcode:2015Geomo.246..589Y. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2015.07.020.

- "Clast Shape, Till Fabrics and Striae". Archived from the original on 2020-11-19. Retrieved 2020-11-25.

- Hermanowski, Piotrowski, Duda (2020). "Till kinematics in the Stargard drumlin field, NW Poland constrained by microstructural proxies". Journal of Quaternary Science. 35 (7): 920–934. Bibcode:2020JQS....35..920H. doi:10.1002/jqs.3233. S2CID 225275064.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Andrews, JT (1971). "Techniques of Till Fabric Analysis". Technical Bulleting, British Geomorphological Society. Archived from the original on 2020-02-19. Retrieved 2020-11-25.

- Shaw, John (April 2002). "The meltwater hypothesis for subglacial bedforms". Quaternary International. 90 (1): 5–22. Bibcode:2002QuInt..90....5S. doi:10.1016/S1040-6182(01)00089-1.

- A satellite image of the region of Hofsjökull where drumlin growth has been observed (see 64°39′25″N 18°41′41″W). The drumlins can be observed between pools of water.

- Paik, Joongcheol; Escauriaza, Cristian; Sotiropoulos, Fotis (1 April 2007). "On the bimodal dynamics of the turbulent horseshoe vortex system in a wing-body junction". Physics of Fluids. 19 (4): 045107–045107–20. Bibcode:2007PhFl...19d5107P. doi:10.1063/1.2716813.

- Shaw, John (June 1994). "Hairpin erosional marks, horseshoe vortices and subglacial erosion". Sedimentary Geology. 91 (1–4): 269–283. Bibcode:1994SedG...91..269S. doi:10.1016/0037-0738(94)90134-1.

- Fiore, Julien Thomas (2007). Quaternary subglacial processes in Switzerland : geomorphology of the Plateau and seismic stratigraphy of Western Lake Geneva (Thesis). doi:10.13097/archive-ouverte/unige:714.

- O'Dwyer, Barry; Crockford, Lucy; Jordan, Phil; Hislop, Lindsay; Taylor, David (July 2013). "A palaeolimnological investigation into nutrient impact and recovery in an agricultural catchment". Journal of Environmental Management. 124: 147–155. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.01.034. PMID 23490624.

- Shaw, John; Sharpe, Davis; Harris, Jeff (January 2010). "A flowline map of glaciated Canada based on remote sensing data". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 47 (1): 89–101. doi:10.1139/E09-068.

- Gray, Charlotte (2004). The Museum Called Canada: 25 Rooms of Wonder. Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-31220-8.

- "Ontario Drumlins". The Creation Concept. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-12-14.

- Smith, D.G (1987). Landforms of Alberta interpreted from airphotos and satellite imagery. Edmonton, Alberta: Alberta Remote Sensing Center, Alberta Environment. pp. 41–43. ISBN 0-919975-10-0.

- Kerr, Michael; Eyles, Nick (January 2007). "Origin of drumlins on the floor of Lake Ontario and in upper New York State". Sedimentary Geology. 193 (1–4): 7–20. Bibcode:2007SedG..193....7K. doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2005.11.025.

- White, William A. (1985). "Drumlins carved by rapid water-rich surges". Northeastern Geology. 7: 161–166.

- Fuller, M. L. (1914). The geology of Long Island, New York. doi:10.3133/pp82.

- Sanders, John E.; Merguerian, Charles. Benimoff, A. I. (ed.). The glacial geology of New York City and vicinity (PDF). The Geology of Staten Island, New York, Field guide and proceedings, The Geological Association of New Jersey, XI Annual Meeting. pp. 93–200. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-03.

- Kehew, Alan E.; Esch, John M.; Kozlowski, Andrew L.; Ewald, Stephanie K. (2012). "Glacial landsystems and dynamics of the Saginaw Lobe of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, Michigan, USA". Quaternary International. 260: 21–31. Bibcode:2012QuInt.260...21K. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.07.021.

- Toimi Uplands Subsection Archived 2016-10-21 at the Wayback Machine of the Northern Superior Uplands, Ecological Classification System. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 2016.

- Goldstein, Barry (June 1994). "Drumlins of the Puget Lowland, Washington State, USA". Sedimentary Geology. 91 (1–4): 299–311. Bibcode:1994SedG...91..299G. doi:10.1016/0037-0738(94)90136-8.

- Prieto V., Ximena; Margaret, Winslow. "El cuaternario del estrecho de Magallanes I: Sector Punta Arenas-Primera Angostura" [Quaternary in Magallanes Strait: Punta Arenas-Primera Angostura] (PDF). Anales del Instituto de la Patagonia (in Spanish). 22: 85–95.

- Smith, A.M.; Murray, T.; Nicholls, K.W.; Makinson, K.; Aðalgeirsdóttir, G.; Behar, A.E.; Vaughan, D.G. (2007). "Rapid erosion, drumlin formation, and changing hydrology beneath an Antarctic ice stream". Geology. 35 (2): 127–130. Bibcode:2007Geo....35..127S. doi:10.1130/G23036A.1.

Further reading

- Bouton, G.S. (1987). "A theory of drumlin formation by subglacial sediment deformation". In Menzies, J.; Rose, J. (eds.). Drumlin Symposium. Taylor & Francis. pp. 25–80. ISBN 978-90-6191-792-2.

- Charlesworth, J. Kaye (1938). "Some Observations on the Glaciation of North-East Ireland". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Section B: Biological, Geological, and Chemical Science. 45: 255–295. JSTOR 20490769.

- Finch, T. F.; Walsh, M. (1973). "Drumlins of County Clare". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Section B: Biological, Geological, and Chemical Science. 73: 405–413. JSTOR 20518928.

- Linton, D. L. (1963). "The Forms of Glacial Erosion". Transactions and Papers (Institute of British Geographers) (33): 1–28. doi:10.2307/620998. JSTOR 620998.

- Menzies, J. (April 1979). "A review of the literature on the formation and location of drumlins". Earth-Science Reviews. 14 (4): 315–359. Bibcode:1979ESRv...14..315M. doi:10.1016/0012-8252(79)90093-X.

- Millis, John (1911). "What Caused the Drumlins?". Science. 34 (863): 60–62. Bibcode:1911Sci....34...60M. doi:10.1126/science.34.863.60. JSTOR 1638735. PMID 17775311.

- Patterson, Carrie J.; Hooke, Roger LeB (1995). "Physical environment of drumlin formation". Journal of Glaciology. 41 (137): 30–38. doi:10.3189/S0022143000017731. S2CID 140583314.

External links

- Diagrams of an idealized drumlin, The Geography Site, United Kingdom. Last accessed January 9, 2023.

- Drumlin field, northwestern Manitoba, image from Canadian Landscapes Photo Collection, Geological Survey of Canada. Last accessed January 9, 2023.

- Word of the day defines drumlin., Anu Garg, A.Word.A.Day. Last accessed January 9, 2023.

- French River: Ice Age Outburst on YouTube. Last accessed January 9, 2023.