John III of Sweden

John III (Swedish: Johan III, Finnish: Juhana III; 20 December 1537 – 17 November 1592) was King of Sweden from 1569 until his death. He was the son of King Gustav I of Sweden and his second wife Margaret Leijonhufvud. He was also, quite autonomously, the ruler of Finland, as Duke John from 1556 to 1563. In 1581 he assumed also the title Grand Prince of Finland. He attained the Swedish throne after a rebellion against his half-brother Eric XIV. He is mainly remembered for his attempts to close the gap between the newly established Lutheran Church of Sweden and the Catholic Church, as well as his conflict with and murder of his brother.

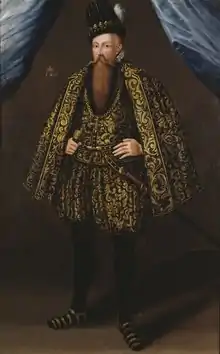

| John III | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Johan Baptista van Uther, 1582 | |

| King of Sweden Grand Duke of Finland | |

| Reign | January 1569 – 17 November 1592 |

| Coronation | 10 July 1569 |

| Predecessor | Eric XIV |

| Successor | Sigismund |

| Born | 20 December 1537 Stegeborg Castle |

| Died | 17 November 1592 (aged 54) Tre Kronor castle |

| Burial | 1 February 1594 |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | Sigismund III, King of Poland and Sweden Anna, Starosta of Brodnica and Golub John, Duke of Östergötland Sophia, Baroness de la Gardie (ill.) Lucretia Gyllenhielm (ill.) |

| House | Vasa |

| Father | Gustav I of Sweden |

| Mother | Margaret Leijonhufvud |

| Religion | mediating between Lutheranism and Catholicism[1] |

| Signature | |

%252C_1568.JPG.webp)

His first wife was Catherine Jagellonica of the Polish-Lithuanian ruling family, and their son Sigismund eventually ascended both the Polish-Lithuanian and Swedish thrones.

Biography

John was the second son of Gustav Vasa (1523–60). His mother was Margaret Leijonhufvud (1514–51), a Swedish noblewoman. Gustav had placed his son in Finland to secure Swedish territory in the eastern Baltic from a Russian threat. John was sent as an emissary to England to secure the hand of Queen Elizabeth I in marriage to his half-brother Crown Prince Erik (1559–60). The marriage would have secured Swedish access to Western Europe. That mission failed, but in England, John observed the reintroduction of Protestantism and the Book of Common Prayer (1559). The Finnish duke had liturgical and theological interests.

As Duke of Finland, he opposed the efforts of his half-brother King Eric XIV (1560–1569) to secure Reval and East Baltic ports. John and his wife, Katarina, were imprisoned in the Gripsholm in 1563 After his release from prison, probably because of his brother's insanity (see Sture Murders), John again joined the opposition of the nobles, deposed Eric and made himself the king. His important ally was his maternal uncle Sten Leijonhufvud, who at deathbed was made Count of Raseborg. Shortly after this John executed his brother's most trusted counsellor, Jöran Persson, whom he held largely responsible for his harsh treatment while in prison.

John further initiated peace talks with Denmark-Norway and Lübeck to end the Scandinavian Seven Years' War but rejected the resulting Treaties of Roskilde (1568) in which his envoys had accepted far-reaching Danish demands. After two more years of fighting, the war was concluded without many Swedish concessions in the Treaty of Stettin (1570). During the following years he successfully fought Russia in the Livonian War, concluded by the Treaty of Plussa in 1583, a war that meant a Swedish reconquest of Narva. As a whole his foreign policy was affected by his connection to Poland of which country his son Sigismund III Vasa was made king in 1587.

In domestic politics John showed clear Catholic sympathies, inspired by his Polish wife, a fact that created frictions to the Swedish clergy and nobility. He sought to enlist the help of the papacy in gaining release of his wife's family assets, which were frozen in Naples. He also allowed Jesuits to secretly staff the Royal Theological College in Stockholm. However, John himself was a learned follower of the mediating theologian George Cassander. He sought reconciliation between Rome and Wittenberg on the basis of the consensus of the first five centuries of Christianity (consensus quinquesaecularis). John approved the publication of the Lutheran Swedish Church Order of Archbishop Laurentius Petri in 1571 but also got the church to approve an addendum to the church order in 1575, Nova ordinantia ecclesiastica that displayed a return to patristic sources.[3] This set the stage for his promulgation of the Swedish-Latin Red Book, entitled Liturgia suecanae ecclesiae catholicae & orthodoxae conformis,[4][5] which reintroduced several Catholic customs and resulted in the Liturgical Struggle, which was not to end for twenty years. In 1575, he gave his permission for the remaining Catholic convents in Sweden to start receiving novices again. From time to time he was also at odds theologically with his younger brother Duke Charles of Sudermannia (afterwards Charles IX of Sweden), who had Calvinist sympathies, and did not promote King John's Liturgy in his duchy. John III was an eager patron of art and architecture. He turned the medieval Kalmar Castle into a Renaissance palace and often resided there because it was closer to Poland.

John III as king

In January 1569, John was recognized as king by the same riksdag that forced Eric XIV off the throne. But this recognition was not without influence from John; Duke Karl received confirmation on his dukedom without the restrictions on his power that the Arboga articles imposed. The nobilities' power and rights were extended and their responsibilities lessened.

John was still concerned about his position as king as long as Eric was alive. During the imprisonment of Eric, three major conspiracies were made to depose John: the 1569 Plot, the Mornay Plot, and the 1576 Plot.[6][7] The fear of a possible liberation of the imprisoned king worried him to the point that in 1571 he ordered the guards to murder the captured king if there were any suspicion of an attempt to liberate him. It is possible that this is how Eric died in 1577.

John III claimed that he had liberated Sweden from the "tyrant" Eric XIV, just as his father had liberated Sweden from the "bloodhound" Christian II. John was violent, hot-tempered, and greatly suspicious.

Family

John married his first wife, Catherine Jagellonica of Poland (1526–83), of the House of Jagiello, in Vilnius on 4 October 1562. In Sweden, she is known as Katarina Jagellonica. She was the sister of king Sigismund II Augustus of Poland. Their children were:

- Isabella (1564–1566)

- Sigismund (1566–1632), King of Poland (1587–1632), King of Sweden (1592–99), and Grand Duke of Finland and Lithuania

- Anna (1568–1625)

He married his second wife, Gunilla Bielke (1568–1592), on 21 February 1585; they had a son:

- John (1589–1618), firstly Duke of Finland, then from 1608 Duke of Ostrogothia. The young duke married his first cousin Maria Elisabet (1596–1618), daughter of Charles IX of Sweden (reigned 1599–1611)

With his mistress Karin Hansdotter (1532–1596) he had at least four illegitimate children:

- Sofia Gyllenhielm (1556–1583), who married Pontus De la Gardie

- Augustus Gyllenhielm (1557–1560)

- Julius Gyllenhielm (1559–1581)

- Lucretia Gyllenhielm (1560–1585)

John cared for Karin and their children even after he married Catherine Jagellonica, in 1562. He got Karin a husband who would care for her and the children: in 1561, she married nobleman Klas Andersson (Västgöte), a friend and servant of John. They had a daughter named Brita. He continued supporting Karin and his illegitimate children as king, from 1568. In 1572 Karin married again, as her first husband was executed for treason by Eric XIV in 1563, to a Lars Henrikson, whom John ennobled in 1576 to care for his issue with Karin. The same year, he made his daughter Sofia a lady in the castle, as a servant to his sister Princess Elizabeth of Sweden. In 1580, John married her to Pontus de la Gardie. She later died giving birth to Jacob De la Gardie.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of John III of Sweden | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- "was not a Lutheran": Encyclopedia of Martin Luther and the Reformation, Volume 2, page 737

- "Vaakuna - Kansallisarkisto". Europeana Heraldica. National Archives of Finland. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- Roland Persson, Johan III och Nova Ordinantia (CWK Glerups 1973)

- Sigtrygg Serenius, Liturgia svecanae ecclesiae catholicae et orthodoxae conformis (Abo 1966)

- Frank C. Senn, Christian Worship – Catholic and Evangelical (Fortress 1997), pp. 421–445

- Karin Tegenborg Falkdalen (2010). Vasadöttrarna (2). Falun: Historiska Media. ISBN 978-91-85873-87-6

- Nordisk familjebok / Uggleupplagan. 7. Egyptologi - Feinschmecker. pp. 787–788

- Signum svenska kulturhistoria: Renässansen (2005).

- Michael Roberts, The Early Vasas: A History of Sweden 1523–1611 (1968).

- Sigtrygg Serenius, Liturgia svecanae ecclesiae catholicae et Orthodoxae conformis (1966).

- Roland Persson, Johan III och Nova Ordinantia (1973).

- Frank C. Senn, Christian Liturgy – Catholic and Evangelical (1997), pp. 421–445.

External links

Media related to John III of Sweden at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to John III of Sweden at Wikimedia Commons