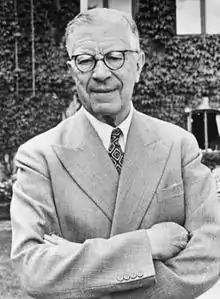

Gustaf VI Adolf

Gustaf VI Adolf (Oscar Fredrik Wilhelm Olaf Gustaf Adolf; 11 November 1882 – 15 September 1973) was King of Sweden from 29 October 1950 until his death in 1973. He was the eldest son of Gustaf V and his wife, Victoria of Baden. Before Gustaf Adolf ascended the throne, he had been crown prince for nearly 43 years during his father's reign. As king, and shortly before his death, he gave his approval to constitutional changes which removed the Swedish monarchy's last nominal political powers. He was a lifelong amateur archeologist particularly interested in Ancient Italian cultures.

| Gustaf VI Adolf | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Gustaf VI Adolf in November 1962 | |||||

| King of Sweden | |||||

| Reign | 29 October 1950 – 15 September 1973 | ||||

| Enthronement | 30 October 1950 | ||||

| Predecessor | Gustaf V | ||||

| Successor | Carl XVI Gustaf | ||||

| Prime ministers | See list | ||||

| Born | 11 November 1882 Stockholm Palace, Stockholm, Sweden | ||||

| Died | 15 September 1973 (aged 90) Helsingborg Hospital, Helsingborg, Sweden | ||||

| Burial | 25 September 1973 | ||||

| Spouses | |||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

| House | Bernadotte | ||||

| Father | Gustaf V of Sweden | ||||

| Mother | Victoria of Baden | ||||

| Religion | Church of Sweden | ||||

| Signature |  | ||||

Birth

He was born at Stockholm Palace and at birth created Duke of Scania. A patrilineal member of the Bernadotte family, he was also a descendant of the House of Vasa through maternal lines. Through his mother, Victoria, he was a descendant of Gustav IV Adolf of the House of Holstein-Gottorp (Swedish line). In addition to this, he was also a great-grandson of Kaiser Wilhelm I of Germany and had a connection to the House of Hohenzollern (his maternal grandmother being the Kaiser’s only daughter).

Crown Prince (1907–1950)

_Adolf_wearing_coronet.jpg.webp)

Gustaf Adolf became Crown Prince of Sweden on the death of his grandfather, King Oscar II on 8 December 1907.

1934–35 trip to the Near East

From September to December 1934, the Crown Prince, Crown Princess Louise, Princess Ingrid and Prince Bertil visited a number of countries in the Near East. The journey began on 13 September from Stockholm. The journey went by rail via Malmö, Berlin and Rome to Messina, where the royals boarded the Swedish Oriental Line motor ship Vasaland, destined for Greece. They stopped at Patras and then the journey continued to Aegion.[1] On 20 September, they arrived in Piraeus, from where the royals took a train to Athens, where they were received by the President of Greece and representatives of government agencies. Furthermore, an excursion was made to Delphi, Nafplio and Delos with the cruiser Hellas. After returning to Athens, Vasaland departed for Thessaloniki on 28 September, where the international fair was visited. On 2 October, they arrived in Istanbul. After the ship dropped anchor, the royals were landed on the Asian side of the strait. The sloop docked at the quay in front of Haydarpaşa railway station. At the platform, President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's caravan waited, in which the journey continued to Ankara. At the station, the guests were received by Atatürk, members of the government and the administration. After his arrival, the Crown Prince visited Atatürk as well as Foreign Minister Tevfik Rüştü Aras. The visit to Ankara lasted from 3 to 5 October. On 5 October, a two-day visit to Bursa was made. The stay in Turkey ended with a four-day incognito break in Istanbul, during which several receptions were held at the Swedish legation.[1]

On 10 October, the royal travelers continued with Vasaland, which arrived on 12 October in Smyrna. From here, the departure took place on 15 October with the president's own train and on the 17 October it arrived in Aleppo, after Prince Bertil and a representative of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs joined the party on the way. In Aleppo, the stay was extended to about 14 days, when the Crown Prince contracted a mild intestinal catarrh due to the stressful climate. On 1 November, the journey continued. The Crown Prince Couple, Princess Ingrid and Prince Bertil then boarded a British military plane and arrived in Baghdad on the same day. The King Ghazi of Iraq met at his country retreat Kasr-el-Zuhoor, from where he accompanied his guests to Bilatt Castle. At all the official events that followed, except for King Ghazi of Iraq, his uncle and father-in-law, King Ali of Hejaz, the President of the Council and members of the Cabinet, the President of the Senate and others.[1] On 6 November, the royals left by train for Khanaqin, where cars were ready to take them to Tehran. At the border, they were received by a representative of the Persian government and in Tehran by the Foreign Minister and the Grand Master of the Ceremonies, as well as representatives of government agencies. The Crown Prince's family went in a procession to the castle, where the Shah for the Crown Prince represented the council president and others were present. The Shah then accompanied the Crown Prince to the Golestan Palace. After several days in the Persian capital, he left for Mazandaran Province to study for three days the ongoing construction work for the Trans-Iranian Railway. He then returned to Tehran to say goodbye to the Shah. The Crown Prince's family then left on 17 November in Volvo cars for Isfahan and Persepolis. In the latter place, the royals lived in the so-called Xerxes' harem and visited the city under the leadership of Professor Ernst Herzfeld. On 25 November, the return journey to Baghdad began over the snowy passes along the Kum-Sultanabad-Kermanshah road, a three-day uninterrupted journey by car.[1]

After a week-long unofficial stay in Baghdad with visits to modern factories and excursions to Ur and Babylon, the Crown Prince Couple and Princess Ingrid left for Damascus on 5 December by plane. Prince Bertil accompanied the car caravan through the desert, where camel troops paraded at Rutbah station. On 6 December, the President of the Syrian Republic hosted a banquet for the Crown Prince's family, who stayed in Syria for four days. During the return journey to Beirut, Baalbek and the ruins of the old sun city were visited. In Beirut, the royals were received with military honors and were guests of the French government. The High Commissioner of the Levant, with whom the Crown Prince and Crown Princess stayed, hosted a dinner, as did the President of the Lebanese Republic.[1] The Crown Prince also visited the new port facilities in Beirut and visited the offices of the Swedish Oriental Line, Volvo and SKF. Furthermore, the journey went to Jerusalem. The royals arrived on 11 December by car in Palestine and met at the border by the English Commissioner for the Northern District. A two-day break was made in Haifa, where the royals lived in the government building on Mount Carmel. Visits were made on board the Swedish Orient Line's motor ship Hemland. During his stay in Haifa, the Crown Prince laid a wreath at the monument to King Faisal I of Iraq. Excursions were made to Capernaum, Acre, Nazareth and Nablus as well as the modern Jewish cooperative colony of Nahallah. The Crown Prince's family arrived in Jerusalem on 13 December and immediately went to their residence during their stay there, the residence of the English High Commissioner. The program for the following days included a two-day break in Jaffa and Tel Aviv. Visits were made to the offices of Volvo, SKF, ASEA and other Swedish companies.[1] A two-day excursion was made around 20 December to Jericho, the Dead Sea, Transjordan's capital Amman and Petra. The travelers were received by the Emir of Transjordan. After their return to Jerusalem, the royals continued immediately with train to Cairo, where they were guests of the Egyptian government. Due to King Fuad's illness, the Prime Minister hosted the reception banquet at Zafaran Palace on 22 December. The royal guests spent Christmas in stillness, partly in a villa at the foot of the pyramids, partly on the Swedish legation. The Crown Prince and Prince Bertil then visited for a couple of days Alexandria. The Swedish consul Carl Wilhelm von Gerber arranged a reception for the governor, the chief officials, the consuls and the judiciary and the Swedish deputy consul and such for the leading trade representatives.[1]

Reign (1950–1973)

On 29 October 1950, Crown Prince Gustaf Adolf became king a few days before his 68th birthday, upon the death of his father, King Gustaf V. He was at the time the world's oldest heir apparent to a monarchy (this in turn was broken by his grandnephew Charles, Prince of Wales on 2 November 2016). On 30 October he took the regal assurance and was enthroned on queen Christina's Silver Throne. He then delivered his accession speech and adopted Plikten framför allt ("Duty before all"), as his personal motto.

During Gustaf VI Adolf's reign, work was underway on a new Instrument of Government to replace the 1809 constitution and produce reforms consistent with the times. Among the reforms sought by some Swedes was the replacement of the monarchy or at least some moderation of the old constitution's provision that "The King alone shall govern the realm."

Gustaf VI Adolf's personal qualities made him popular among the Swedish people and, in turn, this popularity led to strong public opinion in favour of the retention of the monarchy. Gustaf VI Adolf's expertise and interest in a wide range of fields (architecture and botany being but two) made him respected, as did his informal and modest nature and his purposeful avoidance of pomp. While the monarchy had been de facto subordinate to the Riksdag and ministers since the definitive establishment of parliamentary rule in 1917, the king still nominally retained considerable reserve powers. With few exceptions, though, Gustaf Adolf chose to act on the advice of the ministers.

The King died in 1973, at the old hospital in Helsingborg, Scania, close to his summer residence, Sofiero Castle, after a deterioration in his health that culminated in pneumonia. He was succeeded on the throne by his 27-year-old grandson Carl XVI Gustaf, son of the late Prince Gustaf Adolf. He died the day before the election of 1973, which is suggested to have swayed it in support of the incumbent Social Democratic government.[2] In a break with tradition, he was not buried in Riddarholmskyrkan in Stockholm, but in the Royal Cemetery in Haga alongside his wives.

Not long before his death, Gustaf Adolf approved a new constitution that stripped the monarchy of its remaining political powers. The new document took effect in 1975, two years after Gustaf Adolf's death, leaving his grandson as a ceremonial figurehead.

Personal interests

The King's reputation as a "professional amateur professor" was widely known; nationally and internationally, and among his relatives. Gustaf VI Adolf was a devoted archaeologist, and was admitted to the British Academy for his work in botany in 1958. Gustaf VI Adolf participated in archaeological expeditions in China, Greece, Korea and Italy, and founded the Swedish Institute in Rome.

Gustaf VI Adolf had an enormous private library consisting of 80,000 volumes and – nearly more impressively – he actually had read the main part of the books. He had an interest in specialist literature on Chinese art and East Asian history. Throughout his life, King Gustaf VI Adolf was particularly interested in the history of civilization, and he participated in several archaeological expeditions. His other great area of interest was botany, concentrating in flowers and gardening. He was considered an expert on the Rhododendron flower. At Sofiero Castle (the king's summer residence) he created an admired Rhododendron collection.

Like his sons, Prince Gustaf Adolf and Prince Bertil, Gustaf VI Adolf maintained wide, lifelong interests in sports. He enjoyed tennis and golf, and fly fishing for charity. He was president of the Swedish Olympic Committee and the Swedish Sports Confederation from their foundations and until 1933, and these positions were then taken over by his sons in succession, Gustaf Adolf until 1947 and then Bertil until 1997.

According to all six books of memoires by his sons Sigvard[3] and Carl Johan,[4] nephew Lennart[5] and of wives of the two sons,[6] Gustaf Adolf from the 1930s on took a great and abiding interest in removing their royal titles and privileges (because of marriages that were unconstitutional at the time), persuaded his father Gustaf V to do so and to have the Royal Court call the three family members only Mr. Bernadotte.

Family and issue

_Adolf_of_Sweden_w_fam_07729v.jpg.webp)

Gustaf Adolf married Princess Margaret of Connaught on 15 June 1905 in St. George's Chapel, at Windsor Castle. Princess Margaret was the daughter of Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught, third son of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert of the United Kingdom. Gustaf Adolf and Margaret had five children:

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prince Gustaf Adolf, Duke of Västerbotten | 22 April 1906 | 26 January 1947 (aged 40) | Married Princess Sibylla of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, his second cousin; died in a plane crash at Copenhagen Airport, father of King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden |

| Prince Sigvard, Duke of Uppland | 7 June 1907 | 4 February 2002 (aged 94) | later Prince Sigvard Bernadotte, Count of Wisborg |

| Queen Ingrid | 28 March 1910 | 7 November 2000 (aged 90) | Queen of Denmark; wife of Frederick IX of Denmark and mother of Queen Margrethe II of Denmark and Queen Anne-Marie of Greece |

| Prince Bertil, Duke of Halland | 28 February 1912 | 5 January 1997 (aged 84) | married Lillian Davies, no issue |

| Prince Carl Johan, Duke of Dalarna | 31 October 1916 | 5 May 2012 (aged 95) | later Prince Carl Johan Bernadotte, Count of Wisborg. |

Crown Princess Margaret died suddenly on 1 May 1920 with her cause of death given as an infection following surgery. At the time, she was eight months pregnant and expecting their sixth child.

Gustaf Adolf married Lady Louise Mountbatten, formerly Princess Louise of Battenberg, on 3 November 1923 at St. James's Palace with a celebration at Kensington Palace.[7] She was the sister of Lord Mountbatten and aunt of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh and a niece of Empress Alexandra of Russia. She was also a first cousin once removed of her husband’s first wife both being descendants of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. It was Lady Louise who became Queen of Sweden. Both Queen Louise and her stepchildren were great-grandchildren of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom, Crown Princess Margaret having been a first cousin of Queen Louise's mother, Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine.

His second marriage produced only one stillborn daughter on 30 May 1925.

While his first wife visited her native Britain in the early years of their marriage, it was widely rumored in Sweden that Gustaf Adolf had an affair there with operetta star Rosa Grünberg.[8] Swedish vocalist Carl E. Olivebring (1919–2002) in a press interview claimed to be an extramarital son of Gustaf VI Adolf, a claim taken seriously by the king's biographer Kjell Fridh (1944–1998).[9]

King Gustaf VI Adolf of Sweden was the grandfather of his direct successor King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden, of Queen Margrethe II of Denmark and also of former Queen Anne-Marie of Greece.

By his second marriage King Gustaf VI Adolf was an uncle to Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

Honours

Swedish

| Country | Date | Appointment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 November 1882 – 19 October 1950 | Knight with Collar | Royal Order of the Seraphim | |

| 11 November 1882 – 19 October 1950 | Commander Grand Cross | Order of the Sword | |

| 11 November 1882 – 19 October 1950 | Commander Grand Cross | Order of the Polar Star | |

| 1 June 1912 – 19 October 1950 | Commander Grand Cross | Order of Vasa | |

| 11 November 1882 – 19 October 1950 | Knight with Collar | Order of Charles XIII | |

| 18 September 1897 | King Oscar II's Jubilee Commemorative Medal | ||

| 20 September 1906 | Crown Prince Gustaf's and Crown Princess Victoria's Silver Wedding Medal | ||

| 6 June 1907 | King Oscar II and Queen Sofia's Golden Wedding Medal | ||

| 16 June 1928 | King Gustaf V's Jubilee Commemorative Medal | ||

| 16 June 1948 | King Gustaf V's Jubilee Commemorative Medal | ||

- Quasi-Official Orders

- High Protector (and Honorary Knight) of the Order of St John in Sweden

- The Medal Illis quorum meruere labores of the 18th size, 1939[11]

- Gustav V medal for the 300th Anniversary of the New Sweden Settlement, 1938[11]

- St. Eric's Medal, 1938[11]

- Society for the Promotion of Ski Sport and Open Air Life Royal Jubilee Medal (Skid- och friluftsfrämjandets kungliga jubileumsmedalj), 1967[11]

- Swedish Association of Conscript Non-Commissioned Officers Medal of Merit in gold (Värnpliktiga underofficerares riksförbunds förtjänstmedalj i guld)[11]

- Lunds Studentsångförening's badge of honour[11]

Foreign

Norway:

Norway:

- Grand Cross of St. Olav, with Collar, 11 November 1882[12]

- Knight of the Order of the Norwegian Lion, 21 January 1904[13]

- Austria:

.svg.png.webp) Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Royal Order of Leopold

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Royal Order of Leopold Brazil: Grand Cross of the Southern Cross[10]

Brazil: Grand Cross of the Southern Cross[10] Denmark:[16]

Denmark:[16]

- Knight of the Elephant, 28 October 1903

- Cross of Honour of the Order of the Dannebrog, 31 May 1935

- King Christian X's Liberty Medal, 1946[11]

- Grand Commander of the Dannebrog, 24 March 1952

Iceland:

Iceland:

- Medal for the 1000th Anniversary of the Althing (Heiðursmerki Alþingishátíðarinnar), 1930[11]

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Falcon, 26 June 1930[17]

- Collar with Grand Cross Breast Star of the Order of the Falcon, 1954[11]

.svg.png.webp) Egypt: Collar of the Order of Muhammad Ali

Egypt: Collar of the Order of Muhammad Ali.svg.png.webp) Ethiopia: Collar of the Order of Solomon, 1945[18]

Ethiopia: Collar of the Order of Solomon, 1945[18] Finland:

Finland:

- Grand Cross of the White Rose, with Collar, 1925[19]

- 1939–1940 War Commemorative Medal, 1946[lower-alpha 1]

.svg.png.webp) France: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour

France: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour- Germany:

.svg.png.webp) German Empire:

German Empire:

- Knight of the Black Eagle

- Grand Cross of the Red Eagle

.svg.png.webp) Baden: Knight of the House Order of Fidelity[11]

Baden: Knight of the House Order of Fidelity[11] Oldenburg: Grand Cross of the Order of Duke Peter Friedrich Ludwig[11]

Oldenburg: Grand Cross of the Order of Duke Peter Friedrich Ludwig[11].svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp) Ernestine duchies: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order[11]

Ernestine duchies: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order[11].svg.png.webp) Saxony: Knight of the Rue Crown[11]

Saxony: Knight of the Rue Crown[11].svg.png.webp) Prussia: Centenary Medal[11]

Prussia: Centenary Medal[11]- Grand Commander of the House Order of Hohenzollern[11]

Federal Republic of Germany: Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, Special Class

Federal Republic of Germany: Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, Special Class

.svg.png.webp) Greece:

Greece:

.svg.png.webp) Iran: Grand Collar of the Order of Pahlavi

Iran: Grand Collar of the Order of Pahlavi.svg.png.webp) Iraq: Grand Cross of the Two Rivers[11]

Iraq: Grand Cross of the Two Rivers[11]- Italy:

_crowned.svg.png.webp) Kingdom of Italy:[20]

Kingdom of Italy:[20]

- Knight of the Annunciation, 1 April 1905

- Grand Cross of Saints Maurice and Lazarus, 1 April 1905

- Grand Cross of the Crown of Italy, 1 April 1905

Italian Republic: Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic, 14 June 1966

Italian Republic: Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic, 14 June 1966

.svg.png.webp) Japan: Collar of the Order of the Chrysanthemum

Japan: Collar of the Order of the Chrysanthemum Netherlands: Grand Cross of the Netherlands Lion

Netherlands: Grand Cross of the Netherlands Lion.svg.png.webp) Ottoman Empire: Order of Osmanieh, 1st Class[11]

Ottoman Empire: Order of Osmanieh, 1st Class[11] Peru: Grand Cross of the Sun of Peru, in Diamonds

Peru: Grand Cross of the Sun of Peru, in Diamonds.svg.png.webp) Portugal: Grand Cross of the Tower and Sword[12]

Portugal: Grand Cross of the Tower and Sword[12] Romania: Collar of the Order of Carol I[10]

Romania: Collar of the Order of Carol I[10] Russia

Russia

.svg.png.webp) Spain: Knight of the Golden Fleece, 31 January 1910[21]

Spain: Knight of the Golden Fleece, 31 January 1910[21].svg.png.webp) Siam: Knight of the Order of the Royal House of Chakri, 25 October 1911[22]

Siam: Knight of the Order of the Royal House of Chakri, 25 October 1911[22] United Kingdom:

United Kingdom:

- Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order, 12 May 1905[23]

- Honorary Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (civil), 14 June 1905[24]

- Recipient of the King George V Coronation Medal, 1911[11]

- Recipient of the Royal Victorian Chain, 1923[11]

- Recipient of the King George VI Coronation Medal, 1937[11]

- Knight of the Garter, 28 June 1954[25]

Liberia: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Pioneers of Liberia[11]

Liberia: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Pioneers of Liberia[11] Guatemala: Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of the Quetzal[11]

Guatemala: Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of the Quetzal[11] Chile: Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Merit[11]

Chile: Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Merit[11] Tunisia: Grand Cross of the Order of Independence[11]

Tunisia: Grand Cross of the Order of Independence[11] Mexico: Collar of the Order of the Aztec Eagle[11]

Mexico: Collar of the Order of the Aztec Eagle[11].svg.png.webp) Vatican City: Knight with the Collar of the Order of Pope Pius IX[11]

Vatican City: Knight with the Collar of the Order of Pope Pius IX[11]

- Honorary degrees

- Doctor of Philosophy, Lund University (1918)[26]

- Doctor of Laws, Yale University (15 June 1926)[27]

- Doctor of Laws, University of Chicago (25 June 1926)[28]

- Doctor of Laws, Princeton University (1926)[29]

- Doctor of Science, Clark University (1926)[30]

- Doctor of Laws, Cambridge University (4 June 1929)[31]

- Doctor of Laws, University of Dorpat (1932)[32]

- Doctor of Philosophy, Chernivtsi University (1937)[32]

- Doctor of Laws, Lafayette College (6 July 1938)[33]

- Legum Doctor, Harvard University (11 July 1938)[34]

- Legum Doctor, University of Pennsylvania (1938)[35]

- Doctor of Technology, KTH Royal Institute of Technology (1944)[36]

- Doctor of Philosophy, University of Helsinki (1952)[32]

- Honorary Doctorate, Oxford University (19 May 1955)[32]

- Jubilee doctor honoris causa, Lund University (1968)[26]

Military ranks

1902: Underlöjtnant[37]

1902: Underlöjtnant[37] 1903: Lieutenant[38]

1903: Lieutenant[38] 1909: Captain[39]

1909: Captain[39] 1913: Major[39]

1913: Major[39] 1916: Lieutenant colonel[39]

1916: Lieutenant colonel[39] 1918: Colonel[39]

1918: Colonel[39] 1928: Lieutenant general[39]

1928: Lieutenant general[39] 1932: General[40]

1932: General[40]

Honorary military ranks

Admiral (Royal Navy) 1 May 1951[41]

Admiral (Royal Navy) 1 May 1951[41] Colonel-in-Chief, Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) 10 August 1956[42]

Colonel-in-Chief, Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) 10 August 1956[42] Air Chief Marshal (Royal Air Force) 15 September 1959[43]

Air Chief Marshal (Royal Air Force) 15 September 1959[43].svg.png.webp) General (Royal Danish Air Force) 1952[44][11]

General (Royal Danish Air Force) 1952[44][11]

Other Honors

- Caxton Club, Chicago Honorary Member 1952-1973[45]

- In 1938 he was elected an honorary member of the Virginia Society of the Cincinnati

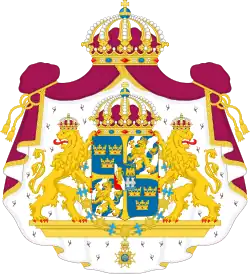

Arms and monogram

Upon his creation as Duke of Skåne, Gustaf Adolf was granted a coat of arms with the arms of Skåne in base. These arms can be seen on his stall-plates both as Knight of the Swedish order of the Seraphim in the Riddarholm Church in Sweden, but also the Frederiksborg Chapel in Copenhagen, Denmark, as a Knight of the Danish Order of the Elephant. Upon his accession to the throne in 1950, he assumed the Royal Arms of Sweden.

As prince of Sweden and Norway and Duke of Scania 1882 to 1905 |

2.svg.png.webp) As crown prince of Sweden and Duke of Scania 1907 to 1950 |

Greater Coat of Arms of Sweden, also the King's coat of arms |

Royal Monogram of King Gustaf VI Adolf of Sweden |

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Gustaf VI Adolf |

|---|

Footnotes

- One of seven gold medals awarded in 1941 by Field Marshal Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim.[11]

References

- Kjellberg, H. E., ed. (1934). Svenska Dagbladets årsbok (Händelserna 1934) [Svenska Dagbladet's yearbook (Events of 1934)] (in Swedish). Vol. 12. Stockholm: Svenska Dagbladet. pp. 73–77. SELIBR 283647.

- Magnusson, Jane (25 November 2011). "När Martin Luther King träffade kungen". Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- Sigvard Bernadotte's memoires

- Carl Johan Bernadotte's memoires

- Lennart Bernadotte's first book & second book

- Marianne Bernadotte's memoires & Kerstin Bernadotte's

- "Royal Wedding 1923". British Pathe News.

- Elgklou, Lars (1978). Bernadotte: historien - och historier - om en familj (in Swedish). Stockholm: Askild & Kärnekull. p. 170. ISBN 91-7008-882-9. SELIBR 7589807.

- Fridh, Kjell (1995). Gamle kungen: Gustaf VI Adolf : en biografi (in Swedish). Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand. ISBN 91-46-16462-6. SELIBR 7281986.

- Sveriges statskalender för året 1947 (in Swedish). Uppsala: Fritzes offentliga publikationer. 1947. p. 5.

- Påhlsson, Leif (25 September 1973). "Kung Gustaf Adolfs medaljer och ordnar" [King Gustaf Adolf's medals and orders]. Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). p. 9. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- Norges Statskalender (in Norwegian), 1890, pp. 589–590, retrieved 6 January 2018 – via runeberg.org

- "The Order of the Norwegian Lion". Royal Court of Norway. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "A Szent István Rend tagjai" Archived 22 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Reply to a parliamentary question" (PDF) (in German). National Council. p. 95. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- Bille-Hansen, A. C.; Holck, Harald, eds. (1969) [1st pub.:1801]. Statshaandbog for Kongeriget Danmark for Aaret 1969 [State Manual of the Kingdom of Denmark for the Year 1969] (PDF). Kongelig Dansk Hof- og Statskalender (in Danish). Copenhagen: J.H. Schultz A.-S. Universitetsbogtrykkeri. pp. 18, 20. Retrieved 29 May 2020 – via da:DIS Danmark.

- "ORÐUHAFASKRÁ" (in Icelandic). President of Iceland. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- "The Imperial Orders and Decorations of Ethiopia Archived 26 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine", The Crown Council of Ethiopia. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- "Suomen Valkoisen Ruusun Suurristi Ketjuineen". ritarikunnat.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Italy. Ministero dell'interno (1920). Calendario generale del regno d'Italia. p. 57.

- Boletín Oficial del Estado. boe.es. 1 February 1910. Vol. L, #32, p. 253

- Royal Thai Government Gazette (5 November 1911). "ส่งเครื่องราชอิสริยาภรณ์ไปพระราชทาน" (PDF) (in Thai). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "No. 27793". The London Gazette (Supplement). 15 May 1905. p. 3513.

- "No. 27807". The London Gazette. 16 June 1905. p. 4251.

- List of Knights of the Garter – 1348 to present – via heraldica.org.

- "Rektors tal vid doktorspromotionen den 25 maj 2018" [Rector's speech at the doctoral promotion on 25 May 2018] (PDF) (in Swedish). Lund University. 25 May 2018. p. 3. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- "SWEDISH PRINCE TO RECEIVE HONORARY DEGREE FROM YALE". The Harvard Crimson (in Swedish). 14 June 1926. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- "Past Honorary Degree Recipients" (in Swedish). University of Chicago. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- "Crown Prince Gustav Adolf of Sweden receives a doctorate at Princeton, 1926" (in Swedish). Bridgeman Images. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- Rudberg, Erik, ed. (1927). Svenska Dagbladets årsbok (Händelserna 1926) [Svenska Dagbladet's yearbook (Events of 1926)] (in Swedish). Vol. 12. Stockholm: Svenska Dagbladet. p. 46. SELIBR 283647.

- "Kronprinsen promoverad till juris hedersdoktor under akademisk ståt" [The Crown Prince promoted to honorary doctor of law under academic status]. Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). 5 June 1929. p. 1. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- "14 gånger hedersdoktor" [14 times honorary doctorate]. Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). 21 May 1955. p. 10A. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- Sandstedt, Sven (7 July 1938). "Två tal av kronprinsen sista jubileumsfestdagen" [Two speeches by the Crown Prince on the last anniversary celebration day]. Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). p. 1. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- "HARVARD TO HONOR PRINCE; Plans to Give Degree to Gustaf Adolf at July 11 Reception". The New York Times (in Swedish). 30 June 1938. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- "Honorary Degree Recipients" (in Swedish). University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- "Honorary doctors at KTH" (in Swedish). KTH Royal Institute of Technology. 28 June 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- Sveriges statskalender för år 1903 (PDF) (in Swedish). Stockholm: P.A. Nordstedt & Söner. 1902. p. 168.

- Sveriges statskalender för skottåret 1908 (PDF) (in Swedish). Stockholm: P.A. Nordstedt & Söner. 1908. p. 129.

- Älmeberg, Roger (2020). Gustaf VI Adolf: regenten som räddade monarkin (in Swedish). [Stockholm]: Norstedts. ISBN 9789113116648. SELIBR fstlmgqwcvcwh6mg.

- Sveriges statskalender för året 1933 (PDF) (in Swedish). Uppsala: Fritzes offentliga publikationer. 1933. p. 239.

- "No. 39237". The London Gazette (Supplement). 25 May 1951. p. 2927.

- "No. 40851". The London Gazette (Supplement). 7 August 1956. p. 4579.

- "No. 43174". The London Gazette (Supplement). 29 November 1963. p. 9907.

- Hånbog for flyvevåbnet 1963-64 (in Danish). Copenhagen: Ministry of Defence. 1963. p. 1.

- The Caxton Club Yearbook 1965 104 and The Caxton Club Yearbook 1971 supplement of 1973

External links

Media related to Gustaf VI Adolf of Sweden at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gustaf VI Adolf of Sweden at Wikimedia Commons- Newspaper clippings about Gustaf VI Adolf in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Portraits of Gustav VI Adolf, King of Sweden at the National Portrait Gallery, London