Human interactions with insects

Human interactions with insects include both a wide variety of uses, whether practical such as for food, textiles, and dyestuffs, or symbolic, as in art, music, and literature, and negative interactions including damage to crops and extensive efforts to control insect pests.

Academically, the interaction of insects and society has been treated in part as cultural entomology, dealing mostly with "advanced" societies, and in part as ethnoentomology, dealing mostly with "primitive" societies, though the distinction is weak and not based on theory. Both academic disciplines explore the parallels, connections and influence of insects on human populations, and vice versa. They are rooted in anthropology and natural history, as well as entomology, the study of insects. Other cultural uses of insects, such as biomimicry, do not necessarily lie within these academic disciplines.

More generally, people make a wide range of uses of insects, both practical and symbolic. On the other hand, attitudes to insects are often negative, and extensive efforts are made to kill them. The widespread use of insecticides has failed to exterminate any insect pest, but has caused resistance to commonly-used chemicals in a thousand insect species.

Practical uses include as food, in medicine, for the valuable textile silk, for dyestuffs such as carmine, in science, where the fruit fly is an important model organism in genetics, and in warfare, where insects were successfully used in the Second World War to spread disease in enemy populations. One insect, the honey bee, provides honey, pollen, royal jelly, propolis and an anti-inflammatory peptide, melittin; its larvae too are eaten in some societies. Medical uses of insects include maggot therapy for wound debridement. Over a thousand protein families have been identified in the saliva of blood-feeding insects; these may provide useful drugs such as anticoagulants, vasodilators, antihistamines and anaesthetics.

Symbolic uses include roles in art, in music (with many songs featuring insects), in film, in literature, in religion, and in mythology. Insect costumes are used in theatrical productions and worn for parties and carnivals.

Context

Culture

Culture consists of the social behaviour and norms found in human societies and transmitted through social learning. Cultural universals in all human societies include expressive forms like art, music, dance, ritual, religion, and technologies like tool usage, cooking, shelter, and clothing. The concept of material culture covers physical expressions such as technology, architecture and art, whereas immaterial culture includes principles of social organization, mythology, philosophy, literature, and science.[1] This article describes the roles played by insects in human culture so defined.

Cultural entomology and ethnoentomology

Ethnoentomology developed from the 19th century with early works by authors such as Alfred Russel Wallace (1852) and Henry Walter Bates (1862). Hans Zinsser's classic Rats, Lice and History (1935) showed that insects were an important force in human history. Writers like William Morton Wheeler, Maurice Maeterlinck, and Jean Henri Fabre described insect life and communicated their meaning to people "with imagination and brilliance". Frederick Simon Bodenheimer's Insects as Human Food (1951) drew attention to the scope and potential of entomophagy, and showed a positive aspect of insects. Food is the most studied topic in ethnoentomology, followed by medicine and beekeeping.[2]

In 1968, Erwin Schimitschek claimed cultural entomology as a branch of insect studies, in a review of the roles insects played in folklore and culture including religion, food, medicine and the arts.[3] In 1984, Charles Hogue covered the field in English and from 1994 to 1997, Hogue's The Cultural Entomology Digest served as a forum on the field.[4][5] Hogue argued that "Humans spend their intellectual energies in three basic areas of activity: surviving, using practical learning (the application of technology); seeking pure knowledge through inductive mental processes (science); and pursuing enlightenment to taste a pleasure by aesthetic exercises that may be referred to as the 'humanities.' Entomology has long been concerned with survival (economic entomology) and scientific study (academic entomology), but the branch of investigation that addresses the influence of insects (and other terrestrial Arthropoda, including arachnids and myriapods) in literature, language, music, the arts, interpretive history, religion, and recreation has only become recognized as a distinct field" through Schimitschek's work.[3][6][7] Hogue set out the boundaries of the field by saying: "The narrative history of the science of entomology is not part of cultural entomology, while the influence of insects on general history would be considered cultural entomology."[8] He added: "Because the term "cultural" is narrowly defined, some aspects normally included in studies of human societies are excluded."[8]

Darrell Addison Posey, noting that the boundary between cultural entomology and ethnoentomology is difficult to draw, cites Hogue as limiting cultural entomology to the influence of insects on "the essence of humanity as expressed in the arts and humanities". Posey notes further that cultural anthropology is usually restricted to the study of "advanced", industrialised, and literate societies, whereas ethnoentomology studies "the entomological concerns of 'primitive' or 'noncivilized' societies". Posey states at once that the division is artificial, complete with an unjustified us/them bias.[2] Brian Morris similarly criticises the way that anthropologists treat non-Western attitudes to nature as monadic and spiritualist, and contrast this "in gnostic fashion" with a simplistic treatment of Western, often 17th-century, mechanistic attitude. Morris considers this "quite unhelpful, if not misleading", and offers instead his own research into the multiple ways that the people of Malawi relate to insects and other animals: "pragmatic, intellectual, realist, practical, aesthetic, symbolic and sacramental."[9]

Benefits and costs

Insect ecosystem services

_pollinating_Avocado_cv.jpg.webp)

The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) report 2005 defines ecosystem services as benefits people obtain from ecosystems, and distinguishes four categories, namely provisioning, regulating, supporting, and cultural. A fundamental tenet is that a few species of arthropod are well understood for their influence on humans (such as honeybees, ants, mosquitoes, and spiders). However, insects offer ecological goods and services.[10] The Xerces Society calculates the economic impact of four ecological services rendered by insects: pollination, recreation (i.e. "the importance of bugs to hunting, fishing, and wildlife observation, including bird-watching"), dung burial, and pest control. The value has been estimated at $153 billion worldwide.[11] As the ant expert[12] E. O. Wilson observed: "If all mankind were to disappear, the world would regenerate back to the rich state of equilibrium that existed ten thousand years ago. If insects were to vanish, the environment would collapse into chaos."[13] A Nova segment on the American Public Broadcasting Service framed the relationship with insects in an urban context: "We humans like to think that we run the world. But even in the heart of our great cities, a rival superpower thrives ... These tiny creatures live all around us in vast numbers, though we hardly even notice them. But in many ways, it is they who really run the show.[14] The Washington Post stated: "We are flying blind in many aspects of preserving the environment, and that's why we are so surprised when a species like the honeybee starts to crash, or an insect we don't want, the Asian tiger mosquito or the fire ant, appears in our midst. In other words: Start thinking about the bugs."[15]

Pests and propaganda

Human attitudes toward insects are often negative, reinforced by sensationalism in the media.[16] This has produced a society that attempts to eliminate insects from daily life.[17] For example, nearly 75 million pounds of broad-spectrum insecticides are manufactured and sold each year for use in American homes and gardens. Annual revenues from insecticide sales to homeowners exceeded $450 million in 2004. Out of the roughly a million species of insects described so far, not more than 1,000 can be regarded as serious pests, and less than 10,000 (about 1%) are even occasional pests.[17] Yet not one species of insect has been permanently eradicated through the use of pesticides. Instead, at least 1,000 species have developed field resistance to pesticides, and extensive harm has been done to beneficial insects including pollinators such as bees.[18]

During the Cold War, the Warsaw Pact countries launched a widespread war against the potato beetle, blaming the introduction of the species from America on the CIA, demonising the species in propaganda posters, and urging children to gather the beetles and kill them.[19]

Practical uses

As food

Entomophagy is the eating of insects. Many edible insects are considered a culinary delicacy in some societies around the world, and Frederick Simon Bodenheimer's Insects as Human Food (1951) drew attention to the scope and potential of entomophagy, but the practice is uncommon and even taboo in other societies. Sometimes insects are considered suitable only for the poor in the third world, but in 1975 Victor Meyer-Rochow suggested that insects could help ease global future food shortages and advocated a change in western attitudes towards cultures in which insects were appreciated as a food item.[20] P. J. Gullan and P. S. Cranston felt that the remedy for this may be marketing of insect dishes as suitably exotic and costly to make them acceptable. They also note that some societies in sub-Saharan Africa prefer caterpillars to beef, while Chakravorty et al. (2011)[21] point out that food insects (highly appreciated in North-East India) are more expensive than meat. The economics, i.e., the costs involved collecting food insects and the money earned through the sale of such insects, have been studied in a Laotian setting by Meyer-Rochow et al. (2008).[22] In Mexico, ant larvae and corixid water boatman eggs are sought out as a form of caviar by gastronomes. In Guangdong, water beetles fetch a high enough price for these insects to be farmed. Especially high prices are fetched in Thailand for the giant water bug Lethocerus indicus.[23]

Insects used in food include honey bee larvae and pupae,[24][25] mopani worms,[26] silkworms,[27] Maguey worms,[28] Witchetty grubs,[29] crickets,[30] grasshoppers[31] and locusts.[32] In Thailand, there are 20,000 farmers rearing crickets, producing some 7,500 tons per year.[33]

In medicine

Insects have been used medicinally in cultures around the world, often according to the Doctrine of Signatures. Thus, the femurs of grasshoppers, which were said to resemble the human liver, were used to treat liver ailments by the indigenous peoples of Mexico.[34] The doctrine was applied in both Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and in Ayurveda. TCM uses arthropods for various purposes; for example, centipede is used to treat tetanus, seizures, and convulsions,[35] while the Chinese Black Mountain Ant, Polyrhachis vicina, is used as a cure all, especially by the elderly, and extracts have been examined as a possible anti-cancer agent.[36] Ayurveda uses insects such as Termite for conditions such as ulcers, rheumatic diseases, anaemia, and pain. The Jatropha leaf miner's larvae are used boiled to induce lactation, reduce fever, and soothe the gastrointestinal tract.[21][37] In contrast, the traditional insect medicine of Africa is local and unformalised.[37] The indigenous peoples of Central America used a wide variety of insects medicinally. Mayans used Army ant soldiers as living sutures.[34] The venom of the Red harvester ant was used to cure rheumatism, arthritis, and poliomyelitis via the immune reaction produced by its sting.[34] Boiled silkworm pupae were taken to treat apoplexy, aphasy, bronchitis, pneumonia, convulsions, haemorrhages, and frequent urination.[34]

Honey bee products are used medicinally in apitherapy across Asia, Europe, Africa, Australia, and the Americas, despite the fact that the honey bee was not introduced to the Americas until the colonization by Spain and Portugal. They are by far the most common medical insect product both historically and currently, and the most frequently referenced of these is honey.[37] It can be applied to skin to treat excessive scar tissue, rashes, and burns,[38] and as an eye poultice to treat infection.[21] Honey is taken for digestive problems and as a general health restorative. It is taken hot to treat colds, cough, throat infections, laryngitis, tuberculosis, and lung diseases.[34] Apitoxin (honey bee venom) is applied via direct stings to relieve arthritis, rheumatism, polyneuritis, and asthma.[34] Propolis, a resinous, waxy mixture collected by honeybees and used as a hive insulator and sealant, is often consumed by menopausal women because of its high hormone content, and it is said to have antibiotic, anesthetic, and anti-inflammatory properties.[34] Royal jelly is used to treat anaemia, gastrointestinal ulcers, arteriosclerosis, hypo- and hypertension, and inhibition of sexual libido.[34] Finally bee bread, or bee pollen, is eaten as a generally health restorative, and is said to help treat both internal and external infections.[34] One of the major peptides in bee venom, melittin, has the potential to treat inflammation in sufferers of rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis.[39]

The rise of antibiotic resistant infections has sparked pharmaceutical research for new resources, including into arthropods.[40]

Maggot therapy uses blowfly larvae to perform wound-cleaning debridement.[41]

Cantharidin, the blister-causing oil found in several families of beetles described by the vague common name Spanish fly has been used as an aphrodisiac in some societies.[39]

Blood-feeding insects like ticks, horseflies, and mosquitoes inject multiple bioactive compounds into their prey. These insects have long been used by practitioners of Eastern Medicine to prevent blood clot formation or thrombosis, suggesting possible applications in scientific medicine.[42] Over 1280 protein families have been associated with the saliva of blood feeding organisms, including inhibitors of platelet aggregation, ADP, arachidonic acid, thrombin, PAF, anticoagulants, vasodilators, vasoconstrictors, antihistamines, sodium channel blockers, complement inhibitors, pore formers, inhibitors of angiogenesis, anaesthetics, AMPs and microbial pattern recognition molecules, and parasite enhancers/activators.[39][43][44][45]

In science and technology

.jpg.webp)

Insects play an important role in biological research. Because of its small size, short generation time and high fecundity, the common fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster was selected as a model organism for studies of the genetics of higher eukaryotes. D. melanogaster has been an essential part of studies into principles like genetic linkage, interactions between genes, chromosomal genetics, evolutionary developmental biology, animal behaviour and evolution. Because genetic systems are well conserved among eukaryotes, understanding basic cellular processes like DNA replication or transcription in fruit flies helps scientists to understand those processes in other eukaryotes, including humans.[46] The genome of D. melanogaster was sequenced in 2000, reflecting the fruit fly's important role in biological research. 70% of the fly genome is similar to the human genome, supporting the Darwinian theory of evolution from a single origin of life.[47]

Some hemipterans are used to produce dyestuffs such as carmine (also called cochineal). The scale insect Dactylopius coccus produces the brilliant red-coloured carminic acid to deter predators. Up to 100,000 scale insects are needed to make a kilogram (2.2 lbs) of cochineal dye.[48][49]

A similarly enormous number of lac bugs are needed to make a kilogram of shellac, a brush-on colourant and wood finish.[50] Additional uses of this traditional product include the waxing of citrus fruits to extend their shelf-life, and the coating of pills to moisture-proof them, provide slow-release or mask the taste of bitter ingredients.[51]

Kermes is a red dye from the dried bodies of the females of a scale insect in the genus Kermes, primarily Kermes vermilio. Kermes are native to the Mediterranean region, living on the sap of the kermes oak. They were used as a red dye by the ancient Greeks and Romans. The kermes dye is a rich red, and has good colour fastness in silk and wool.[52][53][54][55][56]

Insect attributes are sometimes mimicked in architecture, as at the Eastgate Centre, Harare, which uses passive cooling, storing heat in the morning and releasing it in the warm parts of the day.[57] The target of this piece of biomimicry is the structure of the mounds of termites such as Macrotermes michaelseni which effectively cool the nests of these social insects.[58][59] The properties of the Namib desert beetle's exoskeleton, in particular its wing-cases (elytra) which have bumps with hydrophilic (water-attracting) tips and hydrophobic (water-shedding) sides, have been mimicked in a film coating designed for the British Ministry of Defence, to capture water in arid regions.[60][61]

In textiles

_by_Emperor_Huizong.jpg.webp)

Silkworms, the caterpillars and pupae of the moth Bombyx mori, have been reared to produce silk in China from the Neolithic Yangshao period onwards, c. 5000 BC.[62][63] Production spread to India by 140 AD.[64] The caterpillars are fed on mulberry leaves. The cocoon, produced after the fourth moult, is covered with a continuous filament of the silk protein, fibroin, gummed together with sericin. In the traditional process, the gum is removed by soaking in hot water, and the silk is then unwound from the cocoon and reeled. Filaments are spun together to make silk thread.[65] Commerce in silk between China and countries to its west began in ancient times, with silk known from an Egyptian mummy of 1070 BC, and later to the ancient Greeks and Romans. The silk road leading west from China was opened in the 2nd century AD, helping to drive trade in silk and other goods.[66]

In warfare

The use of insects for warfare may have been attempted in the Middle Ages or earlier, but was first systematically researched by several nations during the 20th century. It was put into practice by the Japanese army's Unit 731 in attacks on China during the Second World War, killing almost 500,000 Chinese people with fleas infected with plague and flies infected with cholera.[67][68] Also in the Second World War, the French and Germans explored the use of Colorado beetles to destroy enemy potato crops.[69] During the Cold War, the US Army considered using yellow fever mosquitoes to attack Soviet cities.[67]

Symbolic uses

In mythology and folklore

Insects have appeared in mythology around the world from ancient times. Among the insect groups featuring in myths are the bee, butterfly, cicada, fly, dragonfly, praying mantis and scarab beetle. Scarab beetles held religious and cultural symbolism in Old Egypt, Greece and some shamanistic Old World cultures. The ancient Chinese regarded cicadas as symbols of rebirth or immortality.[23][70] In the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite, the goddess Aphrodite retells the legend of how Eos, the goddess of the dawn, requested Zeus to let her lover Tithonus live forever as an immortal.[71] Zeus granted her request, but, because Eos forgot to ask him to also make Tithonus ageless, Tithonus never died, but he did grow old.[71] Eventually, he became so tiny and shriveled that he turned into the first cicada.[71]

In an ancient Sumerian poem, a fly helps the goddess Inanna when her husband Dumuzid is being chased by galla demons.[72] Flies also appear on Old Babylonian seals as symbols of Nergal, the god of death[72] and fly-shaped lapis lazuli beads were often worn by many different cultures in ancient Mesopotamia, along with other kinds of fly-jewellery.[72] The Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh contains allusions to dragonflies, signifying the impossibility of immortality.[23][70]

Amongst the Arrernte people of Australia, honey ants and witchety grubs served as personal clan totems. In the case of the San bushmen of the Kalahari, it is the praying mantis which holds much cultural significance including creation and zen-like patience in waiting.[23][70]: 9

Insects feature in folklore around the world. In China, farmers traditionally regulated their crop planting according to the Awakening of the Insects, when temperature shifts and monsoon rains bring insects out of hibernation. Most "awakening" customs are related to eating snacks like pancakes, parched beans, pears, and fried corn, symbolizing harmful insects in the field.[73]

In the Great Lakes region of the United States, there is an annual Woollybear Festival that has been celebrated for over 40 years. The larvae of the species Pyrrharctia isabella (commonly known as the isabella tiger moth), with their 13 distinct segments of black and reddish brown, have the reputation in common folklore of being able to forecast the coming winter weather.[74]

There is a common misconception that cockroaches are serious vectors of disease, but while they can carry bacteria they do not travel far, and have no bite or sting.[75][76] Their shells contain a protein, arylphorin, implicated in asthma and other respiratory conditions.[77]

Among the deep-sea fishermen of Greenock in Scotland, there is a belief that if a fly falls into a glass from which a person has been drinking, or is about to drink, it is a sure omen of good luck to the drinker.[78]

Many people believe the urban myth that the daddy longlegs (Opiliones) has the most poisonous bite in the spider world, but that the fangs are too small to penetrate human skin. This is untrue on several counts. None of the known species of harvestmen have venom glands; their chelicerae are not hollowed fangs but grasping claws that are typically very small and definitely not strong enough to break human skin.[79][80]

In Japan, the emergence of fireflies and rhinoceros beetles signify the anticipated changing of the seasons.[81]

In religion

In the Brazilian Amazon, members of the Tupí–Guaraní language family have been observed using Pachycondyla commutata ants during female rite-of-passage ceremonies, and prescribing the sting of Pseudomyrmex spp. for fevers and headaches.[82]

The red harvester ant Pogonomyrmex californicus has been widely used by natives of Southern California and Northern Mexico for hundreds of years in ceremonies conducted to help tribe members acquire spirit helpers through hallucination. During the ritual, young men are sent away from the tribe and consume large quantities of live, unmasticated ants under the supervision of an elderly member of the tribe. Ingestion of ants should lead to a prolonged state of unconsciousness, where dream helpers appear and serve as allies to the dreamer for the rest of his life.[83]

In art

Both the symbolic form and the actual body of insects have been used to adorn humans in ancient and modern times. A recurrent theme for ancient cultures in Europe and the Near East regarded the sacred image of a bee or human with insect features. Often referred to as the bee "goddess", these images were found in gems and stones. An onyx gem from Knossos (ancient Crete) dating to approximately 1500 BC illustrates a Bee goddess with bull horns above her head. In this instance, the figure is surrounded by dogs with wings, most likely representing Hecate and Artemis – gods of the underworld, similar to the Egyptian gods Akeu and Anubis.[84]

Beetlewing art is an ancient craft technique using iridescent beetle wings practiced traditionally in Thailand, Myanmar, India, China and Japan. Beetlewing pieces are used as an adornment to paintings, textiles and jewelry. Different species of metallic wood-boring beetle wings were used depending on the region, but traditionally the most valued were those from beetles belonging to the genus Sternocera. The practice comes from across Asia and Southeast Asia, especially Thailand, Myanmar, Japan, India and China. In Thailand beetlewings were preferred to decorate clothing (shawls and Sabai cloth) and jewellery in former court circles.[85]

_Dragon-fly_moths_spider_beetles_with_strawberries.jpg.webp)

The Canadian entomologist Charles Howard Curran's 1945 book, Insects of the Pacific World, noted women from India and Sri Lanka, who kept 1+1⁄2 inch (38 mm) long, iridescent greenish coppery beetles of the species Chrysochroa ocellata as pets. These living jewels were worn on festive occasions, probably with a small chain attached to one leg anchored to the clothing to prevent escape. Afterwards, the insects were bathed, fed, and housed in decorative cages. Living jewelled beetles have also been worn and kept as pets in Mexico.[86]

Butterflies have long inspired humans with their life cycle, color, and ornate patterns. The novelist Vladimir Nabokov was also a renowned butterfly expert. He published and illustrated many butterfly species, stating:

I discovered in nature the nonutilitarian delights that I sought in art. Both were a form of magic, both were games of intricate enchantment and deception.[87]

It was the aesthetic complexity of insects that led Nabokov to reject natural selection.[88][89]

The naturalist Ian MacRae writes of butterflies:

the animal is at once awkward, flimsy, strange, bouncy in flight, yet beautiful and immensely sympathetic; it is painfully transient, albeit capable of extreme migrations and transformations. Images and phrases such as "kaleidoscopic instabilities," "oxymoron of similarities," "rebellious rainbows," "visible darkness" and "souls of stone" have much in common. They bring together the two terms of a conceptual contradiction, thereby facilitating the mixing of what should be discrete and mutually exclusive categories ... In positing such questions, butterfly science, an inexhaustible, complex, and finely nuanced field, becomes not unlike the human imagination, or the field of literature itself. In the natural history of the animal, we begin to sense its literary and artistic possibilities.[90]

The photographer Kjell Sandved spent 25 years documenting all 26 characters of the Latin alphabet using the wing patterns of butterflies and moths as The Butterfly Alphabet.[91]

In 2011, the artist Anna Collette created over 10,000 individual ceramic insects at Nottingham Castle, "Stirring the Swarm". Reviews of the exhibit offered a compelling narrative for cultural entomology: "the unexpected use of materials, dark overtones, and the straightforward impact of thousands of tiny multiples within the space. The exhibition was at once both exquisitely beautiful and deeply repulsive, and this strange duality was fascinating."[92][93]

In literature and film

The Ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus has a gadfly pursue and torment Io, a maiden associated with the moon, watched constantly by the eyes of the herdsman Argus, associated with all the stars: "Io: Ah! Hah! Again the prick, the stab of gadfly-sting! O earth, earth, hide, the hollow shape—Argus—that evil thing—the hundred-eyed." William Shakespeare, inspired by Aeschylus, has Tom o'Bedlam in King Lear, "Whom the foul fiend hath led through fire and through flame, through ford and whirlpool, o'er bog and quagmire", driven mad by the constant pursuit.[94] In Antony and Cleopatra, Shakespeare similarly likens Cleopatra's hasty departure from the Actium battlefield to that of a cow chased by a gadfly.[95] H. G. Wells introduced giant wasps in his 1904 novel The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth,[96] making use of the newly discovered growth hormones to lend plausibility to his science fiction.[97] Lafcadio Hearn's essay Butterflies analyses the treatment of the butterfly in Japanese literature, both prose and poetry. He notes that these often allude to Chinese tales, such as of the young woman that the butterflies took to be a flower. He translates 22 Japanese haiku poems about butterflies, including one by the haiku master Matsuo Bashō, said to suggest happiness in springtime: "Wake up! Wake up!—I will make thee my comrade, thou sleeping butterfly."[98]

The novelist Vladimir Nabokov was the son of a professional lepidopterist, and was interested in butterflies himself.[99] He wrote his novel Lolita while travelling on his annual butterfly-collection trips in the western United States.[100] He eventually became a leading lepidopterist. This is reflected in his fiction, where for example The Gift devotes two whole chapters (of five) to the tale of a father and son on a butterfly expedition.[101]

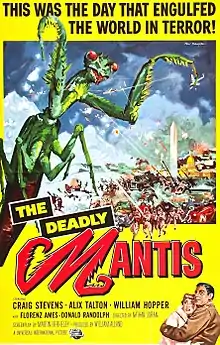

Horror films involving insects, sometimes called "big bug movies", include the pioneering 1954 Them!, featuring giant ants mutated by radiation, and the 1957 The Deadly Mantis.[102][103][104]

The Far Side, a newspaper cartoon, has been used by professor of Michael Burgett as a teaching tool in his entomology class; The Far Side and its author Gary Larson have been acknowledged by biologist Dale H. Clayton his colleague for "the enormous contribution" Larson has made to their field through his cartoons.[105][106]

In music

Some popular and influential pieces of music have had insects as their subjects. The French Renaissance composer Josquin des Prez wrote a frottola entitled El Grillo (lit. 'The Cricket'). It is among the most frequently sung of his works.[107] Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov wrote the "Flight of the Bumblebee" in 1899–1900 as part of his opera The Tale of Tsar Saltan. The piece is one of the most recognizable pieces in classical composition. The bumblebee in the story is a prince who has been transformed into an insect so that he can fly off to visit his father.[108][109][110] The play upon which the opera was based – written by Alexander Pushkin – originally had two more insect themes: the Flight of the Mosquito and the Flight of the Fly.[111] The Hungarian composer Béla Bartók explained in his diary that he was attempting to depict the desperate attempts to escape of a fly caught in a cobweb in his piece From the Diary of a Fly, for piano (Mikrokosmos Vol. 6/142).[112]

The jazz musician and philosophy professor David Rothenberg plays duets with singing insects including cicadas, crickets, and beetles.[113]

In astronomy and cosmology

In astronomy, constellations named after arthropods include the zodiacal Scorpius, the scorpion,[114][115] and Musca, the fly, also known as Apis, the bee, in the deep southern sky. Musca, the only recognised insect constellation, was named by Petrus Plancius in 1597.[116]

"The Bug Nebula", also called "The Butterfly Nebula", is a more recent discovery. Known as NGC 6302 is one of the brightest and most popular stars in the universe – popular in that its features draw the attention of a lot of researchers. It happens to be located in the Scorpius constellation. It is perfectly bipolar, and until recently, the central star was unobservable, clouded by gas, but estimated to be one of the hottest in the galaxy – 200,000 degrees Fahrenheit, perhaps 35 times hotter than the Sun.[117][118]

The honey bee played a central role in the cosmology of the Mayan people. The stucco figure at the temples of Tulum known as "Ah Mucen Kab" – the Diving Bee God – bears resemblance to the insect in the Codex Tro-Cortesianus identified as a bee. Such reliefs might have indicated towns and villages that produce honey. Modern Mayan authorities say the figure also have a connection to modern cosmology. Mayan mythology expert Migel Angel Vergara relates that the Mayans held a belief that bees came from Venus, the "Second Sun." The relief might be indicative of another "insect deity", that of Xux Ex, the Mayan "wasp star."[119] The Mayan embodied Venus in the form of the god Kukulkán (also known as or related to Gukumatz and Quetzalcoatl in other parts of Mexico), Quetzalcoatl is a Mesoamerican deity whose name in Nahuatl means "feathered serpent". The cult was the first Mesoamerican religion to transcend the old Classic Period linguistic and ethnic divisions. This cult facilitated communication and peaceful trade among peoples of many different social and ethnic backgrounds.[120] Although the cult was originally centered on the ancient city of Chichén Itzá in the modern Mexican state of Yucatán, it spread as far as the Guatemalan highlands.[121]

In costumes

Bee and other insect costumes are worn in a variety of countries for parties, carnivals and other celebrations.[122][123]

Ovo is an insect-themed production by the world renowned Canadian entertainment company Cirque du Soleil. The show looks at the world of insects and its biodiversity where they go about their daily lives until a mysterious egg appears in their midst, as the insects become awestruck about this iconic object that represents the enigma and cycles of their lives. The costuming was a fusion of arthropod body types blended with superhero armour. Liz Vandal, the lead costume designer, has a special affinity for the world of the insect:[124]

When I was just a kid I put rocks down around the yard near the fruit trees and I lifted them regularly to watch the insects who had taken up residence underneath them. I petted caterpillars and let butterflies into the house. So when I learned that OVO was inspired by insects, I immediately knew that I was in a perfect position to pay tribute to this majestic world with my costumes. All insects are beautiful and perfect; it is what they evoke for each of us that changes our perception of them."[124]

The Webby award-winning video series Green Porno was created to showcase the reproductive habits of insects. Jody Shapiro and Rick Gilbert were responsible for translating the research and concepts that Isabella Rossellini envisioned into the paper and paste costumes which directly contribute to the series' unique visual style. The film series was driven by the creation of costumes to translate scientific research into "something visual and how to make it comical."[125]

See also

References

- Macionis, John J.; Gerber, Linda Marie (2011). Sociology. Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 53. ISBN 978-0137001613. OCLC 652430995.

- Posey, Darrell Addison (1986). "Topics And Issues In Ethnoentomology With Some Suggestions For The Development Of Hypothesis-Generation And Testing In Ethnobiology" (PDF). Journal of Ethnobiology. 6 (1): 99–120. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 August 2014.

- Schimitschek, E. (1968). "Insekten als Nahrung, Brauchtum, Kult und Kultur". In Helmcke J.G.; Stark D.; Wermuth H. (eds.). Handbuch der Zoologie. Vol. 4. Berliner Akademie Verlag. pp. 1–62.

- Hogue, Charles. "Cultural Entomology". Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- "Who? What? Why?". Cultural Entomology Digest. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Schimitschek, E. (1961). "Die Bedeutung der Insekten für Kultur und Wirtschaft des Menschen in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart". Istanbul Universitesi. 908: 1–48.

- Hogue, Charles (January 1987). "Cultural Entomology". Annual Review of Entomology. 32: 181–199. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.32.010187.001145.

- Hogue, Charles. "Cultural Entomology". Cultural Entomology Digest. Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Morris, 2006.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being : synthesis (PDF). Washington, DC: Island Press. ISBN 1-59726-040-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Lyman Kirst, Marian (29 Dec 2011). "Insect – the neglected 99%". High Country News. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- "Edward O. Wilson Biography". Biography.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- Wilson, E.O. (2006). The Creation: An Appeal to Save Life on Earth. Norton. ISBN 9780393062175.

- "Little Creatures Who Run the World". Nova. PBS Airdate: August 12, 1997. Archived from the original on October 1, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Higgins, Adrian (30 June 2007). "Saving Earth From the Ground Up". June 30, 2007. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Kellert, S. R. (1993). "Values and perceptions of invertebrates". Conservation Biology. 7 (4): 845–855. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1993.740845.x.

- Meyer, John (2006). "Chapter 18: Insects As Pests". North Carolina State University. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Miller G.T. (2004). Sustaining the Earth (6th ed.). Thompson Learning. pp. 211–216.

- Sindelar, Daisy (29 April 2014). "What's Orange and Black and Bugging Ukraine?". Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

Ukraine’s Reins Weaken as Chaos Spreads Archived 2017-08-23 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times (4 May 2014) - Meyer-Rochow, Victor Benno (1975). "Can insects help to ease the problem of world food shortage?". ANZAAS Journal: "Search". 6 (7): 261–262.

- Chakravorty, J., Ghosh, S., and V. B. Meyer-Rochow. (2011). Practices of entomophagy and entomotherapy by members of the Nyishi and Galo tribes, two ethnic groups of the state of Arunachal Pradesh (North-East India). Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 7 (5)

- Meyer-Rochow V. B., Nonaka K., Boulidam S. (2008) More feared than revered: Insects and their impacts on human societies (with specific data on the importance of entomophagy in a Laotian setting. Entomologie Heute 20: 3–25

- Gullan, P. J.; Cranston, P. S. (2009). The Insects: An Outline of Entomology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 9–13. ISBN 978-1-4051-4457-5.

- Holland, Jennifer (14 May 2013). "U.N. Urges Eating Insects: 8 Popular Bugs to Try". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- Haris, Emmaria (6 December 2013). "Sensasi Rasa Unik Botok Lebah yang Menyengat (Unique taste sensation botok with stinging bees)" (in Indonesian). Sayangi.com. Archived from the original on 22 June 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- "Worms! A look at Zimbabwe's favorite snack: mopane worms". New York Daily News. 25 January 2013. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- Robinson, Martin; Bartlett, Ray; Whyte, Rob. Korea (2007). Lonely Planet publications, ISBN 1-74104-558-4, ISBN 978-1-74104-558-1. page 63

- Tang, Philip. "The 10 tastiest insects and bugs in Mexico". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- Isaacs, Jennifer (2002). Bush Food: Aboriginal Food and Herbal Medicine. Frenchs Forest, New South Wales: New Holland Publishers (Australia). pp. 190–192. ISBN 1-86436-816-0.

- Bray, Adam (24 August 2010). "Vietnam's most challenging foods". CNN: Travel. Archived from the original on 3 June 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- Kenyon, Chelsie. "Chapulines". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Fromme, Alison (2005). "Edible Insects". Smithsonian Zoogoer. Smithsonian Institution. 34 (4). Archived from the original on November 11, 2005. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- Hanboonsong, Yupa; Tasanee, Jamjanya (2013-03-01). "Six-legged livestock" (PDF). FAO. Patrick B. Durst. Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-21. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- Ramos-Elorduy de Concini, J. and J.M. Pino Moreno. (1988). The utilization of insects in the empirical medicine of ancient Mexicans. Journal of Ethnobiology, 8(2), 195–202.

- "Wu Gong, Centipede, Acupuncture, Traditional Chinese Medicine, Acupuncture. Chinese Herb Picture, weblog, discussion board, bulletin board, forums". Archived from the original on 2012-09-17. Retrieved 2016-04-02.

- "BBC News | HEALTH | Insects boost immune system". 10 February 2002. Archived from the original on 2018-02-28. Retrieved 2016-04-02.

- Srivastava, S.K., Babu, N., and H. Pandey. (2009). Traditional insect bioprospecting—As human food and medicine. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge, 8(4): 485–494.

- Feng, Y., Zhao, M., He, Z., Chen, Z., and L. Sun. (2009). Research and utilization of medicinal insects in China. Entomological Research, 39: 313–316.

- Ratcliffe, N.A. et al. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 41 (2011) 747e769

- Dossey, A. T., 2010. Insects and their chemical weaponry: new potential for drug discovery. Nat. Prod. Rep 27, 1737e1757.

- Sun, Xinjuan; Jiang, Kechun; Chen, Jingan; Wu, Liang; Lu, Hui; Wang, Aiping; Wang, Jianming (2014). "A systematic review of maggot debridement therapy for chronically infected wounds and ulcers". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 25: 32–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2014.03.1397. PMID 24841930.

- Yang, X., Hu, K., Yan, G., et al., 2000. Fibrinogenolytic components in Tabanid, an ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine and their properties. J. Southwest Agric. Univ. 22, 173e176 (Chinese).

- Ribeiro, J.M.C., Arca, B., 2009. From sialomes to the sialoverse: an insight into salivary potion of blood-feeding insects. Adv. Insect Physiol. 37, 59e118.

- Francischetti, I.M.B., Mather, T.N., Ribeiro, J.M.C., 2005. Tick saliva is a potent inhibitor of endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Thromb. Haemost. 94, 167e174.

- Maritz-Olivier, C., Stutzer, C., Jongejan, F., et al., 2007. Tick anti-hemostatics: targets for future vaccines and therapeutics. Trends Parasitol. 23, 397e407.

- Pierce, BA (2006). Genetics: A Conceptual Approach (2nd ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. p. 87. ISBN 0-7167-8881-0.

- Adams, MD; Celniker, SE; Holt, RA; Evans, CA; Gocayne, JD; Amanatides, PG; Scherer, SE; Li, PW; et al. (24 March 2000). "The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster". Science. 287 (5461): 2185–2195. Bibcode:2000Sci...287.2185.. doi:10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. PMID 10731132.

- "Cochineal and Carmine". Major colourants and dyestuffs, mainly produced in horticultural systems. FAO. Archived from the original on March 6, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- "Guidance for Industry: Cochineal Extract and Carmine". FDA. Archived from the original on 13 July 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- "How Shellac Is Manufactured". The Mail (Adelaide, SA : 1912 – 1954). 18 Dec 1937. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- Pearnchob, N.; Siepmann, J.; Bodmeier, R. (2003). "Pharmaceutical applications of shellac: moisture-protective and taste-masking coatings and extended-release matrix tablets". Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy. 29 (8): 925–938. doi:10.1081/ddc-120024188. PMID 14570313. S2CID 13150932.

- Barber, E. J. W. (1991). Prehistoric Textiles. Princeton University Press. pp. 230–231. ISBN 0-691-00224-X.

- Goodwin, Jill (1982). A Dyer's Manual. Pelham. ISBN 0-7207-1327-7.

- Schoeser, Mary (2007). Silk. Yale University Press. pp. 118, 121, 248. ISBN 978-0-300-11741-7.

- Munro, John H. (2007). Netherton, Robin; Owen-Crocker, Gale R. (eds.). The Anti-Red Shift – To the Dark Side: Colour Changes in Flemish Luxury Woollens, 1300–1500. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-1-84383-291-1.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Munro, John H. (2003). Jenkins, David (ed.). Medieval Woollens: Textiles, Technology, and Organisation. Cambridge University Press. pp. 214–215. ISBN 0-521-34107-8.

- "Biomimetic Building Uses Termite Mound As Model". Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- "Termite research". esf.edu. Archived from the original on 14 August 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- Pappagallo, Linda (30 January 2012). "Termite Mounds Inspire Energy Neutral Buildings". Green Prophet. Archived from the original on 8 June 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- "Namib Desert beetle inspires self-filling water bottle". BBC. 23 November 2012. Archived from the original on 18 July 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- Trivedi, Bijal P. "Beetle's Shell Offers Clues to Harvesting Water in the Desert". National Geographic Today. Archived from the original on November 5, 2001. Retrieved November 1, 2001.

- Vainker, Shelagh (2004). Chinese Silk: A Cultural History. Rutgers University Press. p. 20. ISBN 0813534461.

- Barber, E. J. W. (1992). Prehistoric textiles: the development of cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with special reference to the Aegean (reprint, illustrated ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-691-00224-8. Archived from the original on 6 November 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- Department of Sericulture. "History of Sericulture" (PDF). Government of Andhra Pradesh (India). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- Bezzina, Neville. "Silk Production Process". Sense of Nature Research. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012.

- Christian, David (2000). "Silk Roads or Steppe Roads? The Silk Roads in World History". Journal of World History. 2 (1): 1. doi:10.1353/jwh.2000.0004. S2CID 18008906.

- Lockwood, Jeffrey A. (24 October 2008). "Six-legged soldiers". The Scientist. Archived from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- Lockwood, Jeffrey A. (2009). Six-Legged Soldiers: Using Insects as Weapons of War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-73353-8.

- Lockwood, Jeffrey A. (21 October 2007). "Bug Bomb. Why our next terrorist attack could come on six legs". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- Gullan, P.J.; Cranston, P.S. (2005). The Insects: An Outline of Entomology (3 ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-1113-5.

- DuBois, Page (2010). Out of Athens: The New Ancient Greeks. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 51–53. ISBN 978-0-674-03558-4. Archived from the original on 2021-11-06. Retrieved 2020-10-22.

- Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992). Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. The British Museum Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 0-7141-1705-6. Archived from the original on 2020-11-20. Retrieved 2020-10-22.

- Shu, Catherine (27 February 2009). "South Village welcomes spring with snacks — and an eye on environmental awareness". Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- "Predicting Winter Weather: Woolly Bear Caterpillars". The Old Farmer's Almanac 2009. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- Roth, L. M.; Willis, E. R. (1960). "The biotic associations of cockroaches". Smithsonian Misc. Collect. 141: 1–470.

- "What are Cockroaches?". Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- Arruda, L. K; Chapman, M. D. (Jan 2001). "What are the cockroach asthma antigens?". Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 7 (1): 14–19. doi:10.1097/00063198-200101000-00003. PMID 11140401. S2CID 41075492.

- Cowan, Frank (1865). Curious Facts in the History of Insects. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co. Notes and Queries, xii. OCLC 1135622330.

- "Just Plain Weird Stories". Archived from the original on 10 August 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- "Daddy Longleg myth". Myth Busters. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- Takada, Kenta (2012). "Japanese Interest in "Hotaru" (Fireflies) and "Kabuto-Mushi" (Japanese Rhinoceros Beetles) Corresponds with Seasonality in Visible Abundance". Insects. 3 (4): 423–431. doi:10.3390/insects3020424. PMC 4553602. PMID 26466535.

- William Balée (2000), "Antiquity of Traditional Ethnobiological Knowledge in Amazonia: a Tupí–Guaraní Family and Time" Ethnohistory 47(2):399–422.

- Kevin Groark. Taxonomic Identity of "Hallucinogenic" Harvester Ant (Pogonomyrmex californicus) Confirmed. 2001. Journal of Ethnobiology 21(2):133–144

- Gough, Andrew. "The Bee Part 2 Beewildered". Archived from the original on 12 July 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- "A Beetle-Wing Tea-Cosy". Hampshire Cultural Trust. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- Rivers, Victoria. "Beetles in Textiles". Cultural Entomology Digest February. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- Nabokov, Vladimir (1989). Speak, Memory. New York: Vintage International. p. 129. Archived from the original on 2014-04-26. Retrieved 2012-10-17.

- Ahuja, Nitin. "Nabokov's Case Against Natural Selection". Tract. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- Nabokov, Vladimir (1990). Strong Opinions. Vintage International. ISBN 9780679726098.

- MacRae, Ian. "Butterfly Chronicles: Imagination and Desire in Natural & Literary Histories". Canadian Journal of Environ Education.

- "Kjell Sandved's Scaly Type". Archived from the original on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- French, Anneka. "Stirring the Swarm". Archived from the original on 6 November 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- "Stirring the Swarm". Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- Stagman, Myron (11 August 2010). Shakespeare's Greek Drama Secret. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 205–208. ISBN 978-1-4438-2466-8.

- Walker, John Lewis (2002). Shakespeare and the Classical Tradition: An Annotated Bibliography, 1961–1991. Taylor & Francis. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-8240-6697-0.

- Wells, H. G. (1904). Food of the Gods. Macmillan.

- Rothman, Sheila; Rothman, David (2011). The Pursuit of Perfection: The Promise and Perils of Medical Enhancement. Knopf Doubleday. pp. 49–. ISBN 978-0-307-76713-4. Archived from the original on 2020-01-05. Retrieved 2016-09-24.

- Hearn, Lafcadio (2015). Insect Literature (Limited (300 copies) ed.). Dublin: Swan River Press. pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-1-78380-009-4.

- Nabokov, Vladimir (April 2000). "Father's Butterflies". The Atlantic Online. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- Amis, Martin (1994) [1993]. Visiting Mrs Nabokov: And Other Excursions. Penguin Books. pp. 115–18. ISBN 0-14-023858-1.

- Boyd, Brian (April 2000). "Nabokov's Butterflies, Introduction". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- Gregersdotter, Katarina; Höglund, Johan; Hållén, Nicklas (2016). Animal Horror Cinema: Genre, History and Criticism. Springer. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-137-49639-3.

- Warren, Bill; Thomas, Bill (2009). Keep Watching the Skies!: American Science Fiction Movies of the Fifties, The 21st Century Edition. McFarland. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4766-2505-8.

- Crouse, Richard (2008). Son of the 100 Best Movies You've Never Seen. ECW Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-55490-330-6.

- All Things Considered (4 January 2005), "'Far Side' Entomology Class Has Students Abuzz", NPR, archived from the original on 10 October 2016, retrieved 9 July 2016

- Larson, Gary (1989). The Prehistory of the Far Side. Andrews and McMeel. ISBN 0-8362-1851-5.

- Macey, Patrick (1998). Bonfire Songs: Savonarola's Musical Legacy. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-19-816669-6.

- "Rimsky-Korsakov – The Flight of the Bumblebee (Homeschool Music Appreciation)". Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ""Eric Speed, Violinist, Flight of the Bumblebee, Nikon S9100, Montreal, 22 July 2011"". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2013-07-27. Retrieved 2012-04-21.

- "The Green Hornet". YouTube. Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- Neff, Lyle (1999). "The Tale of Tsar Saltan: A Centenary Appreciation of Rimski-Korsakov's Second Puškin Opera". The Pushkin Review. 2: 89–133.

- "From the Diary of a Fly, for piano (Mikrokosmos Vol. 6/142), Sz.107/6/142, BB 105/142". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 15 November 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- "David Rothenberg: "Bug Music: How Insects Gave Us Rhythm and Noise"". The Diana Rehm Show. Archived from the original on 2016-04-21. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Mark R. Chartrand III (1983) Skyguide: A Field Guide for Amateur Astronomers, p. 184 (ISBN 0-307-13667-1).

- Constellations: A Guide to the Night Sky, http://www.constellation-guide.com/constellation-list/scorpius-constellation/ Archived 2016-06-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Ridpath, Ian. "Frederick de Houtman's Catalogue". Star Tales. Archived from the original on 24 August 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- Matsuura, M.; Zijlstra, A. A.; Molster, F. J.; Waters, L. B. F. M.; Nomura, H.; Sahai, R.; Hoare, M. G. (2005). "The dark lane of the planetary nebula NGC 6302". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 359 (1): 383–400. Bibcode:2005MNRAS.359..383M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.08903.x.

- "Newly discovered star one of hottest in Galaxy". Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- Hunter, C. Bruce (1975). A Guide to Ancient Maya Ruins. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-8061-1992-2. Archived from the original on 2021-11-06. Retrieved 2020-10-22.

- Sharer, Robert J; Traxler, Loa P. (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. pp. 582–3. ISBN 0-8047-4817-9.

- Sharer, Robert J; Traxler, Loa P. (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. p. 619. ISBN 0-8047-4817-9.

- Philippines. Lonely Planet. 2000. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-86442-711-3. Archived from the original on 2016-07-22. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- Frank, Ze (2011). Young Me, Now Me: Identical Photos, Different Decades. Ulysses Press. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-1-61243-006-5. Archived from the original on 2020-01-04. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- "About the Show". Cirque du Soleil. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- Kung, Michelle. ""Green Porno" Creator Isabella Rossellini on Animal Sex, Crazed Fans and Web Entertainment". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

Further reading

- Hogue, James N. (2003). "Cultural Entomology". In Vincent H. Resh, Ring T. Cardé (ed.). Encyclopedia of Insects. Academic Press. pp. 273–281. ISBN 0-08-054605-6.

- Marren, Peter; Mabey, Richard (2010). Bugs Britannica. Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-8180-2.

- Meyer-Rochow, V. B.; et al. (2008). "More feared than revered: Insects and their impact on human societies (with specific data on the importance of entomophagy in a Laotian setting)". Entomologie Heute. 20: 3–25.

- Morris, Brian (2006) [2004]. Cultural Entomology. pp. 181–216. ISBN 978-1-84520-949-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)