Battle of Actium

The Battle of Actium was a naval battle fought between Octavian's maritime fleet, led by Marcus Agrippa, and the combined fleets of both Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII Philopator. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC in the Ionian Sea, near the former Roman colony of Actium, Greece, and was the climax of over a decade of rivalry between Octavian and Antony.

| Battle of Actium | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of Actium | |||||||

Anachronistic baroque painting of the battle of Actium by Laureys a Castro, 1672 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Romans supporting Octavian |

Romans supporting Antony Ptolemaic Egypt | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Octavian Marcus Agrippa Lucius Arruntius Marcus Lurius |

Mark Antony Gaius Sosius Lucius Gellius Poplicola Cleopatra | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

400 galleys 3,000 archers 16,000 infantry on ships[1][2][3] |

250 larger galleys 30–50 transports 20,000 infantry on ships 2,000 archers[1][2][3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| About 2,500 killed |

Over 5,000 killed 250 ships sunk or captured | ||||||

Location within Greece  Battle of Actium (Mediterranean)  Battle of Actium (Europe) | |||||||

In early 31 BC, the year of the battle, Antony and Cleopatra were temporarily stationed in Greece. Mark Antony possessed 500 ships and 70,000 infantry, and made his camp at Actium, and Octavian, with 400 ships and 80,000 infantry, arrived from the north and occupied Patrae and Corinth, where he managed to cut Antony's southward communications with Egypt (via the Peloponnese) with help from Marcus Agrippa. Octavian previously gained a preliminary victory in Greece, where his navy successfully ferried troops across the Adriatic Sea under the command of Marcus Agrippa. Octavian landed on mainland Greece, opposite of the island of Corcyra (modern Corfu) and proceeded south, on land.

Trapped on both land and sea, portions of Antony's army deserted and fled to Octavian's side (daily), and Octavian's forces became comfortable enough to make preparations for battle.[4] Antony's fleet sailed through the bay of Actium on the western coast of Greece, in a desperate attempt to break free of the naval blockade. It was there that Antony's fleet faced the much larger fleet of smaller, more manoeuvrable ships under commanders Gaius Sosius and Agrippa.[5] Antony and his remaining forces were spared only due to a last-ditch effort by Cleopatra's fleet that had been waiting nearby.[6] Octavian pursued them and defeated their forces in Alexandria on 1 August 30 BC—after which Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide.

Octavian's victory enabled him to consolidate his power over Rome and its dominions. He adopted the title of Princeps ("first citizen"), and in 27 BC was awarded the title of Augustus ("revered") by the Roman Senate. This became the name by which he was known in later times. As Augustus, he retained the trappings of a restored Republican leader, but historians generally view his consolidation of power and the adoption of these honorifics as the end of the Roman Republic and the beginning of the Roman Empire.[7]

Background

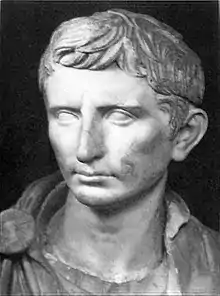

The alliance among Octavian, Mark Antony and Lepidus, commonly known as the Second Triumvirate, was renewed for a five-year term at Tarentum in 37 BC.[8] However, the triumvirate broke down when Octavian saw Caesarion, the professed son of Julius Caesar[9] and Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt, as a major threat to his power.[10] This occurred when Mark Antony, the other most influential member of the triumvirate, abandoned his wife, Octavian's sister Octavia Minor. Afterward he moved to Egypt to start a long-term romance with Cleopatra, becoming Caesarion's de facto stepfather. Octavian and the majority of the Roman Senate saw Antony as leading a separatist movement that threatened to break the Roman Republic's unity.

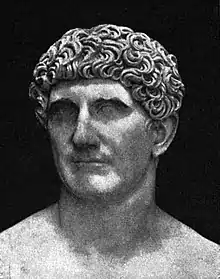

Octavian's prestige and, more importantly, his legions' loyalty had been boosted by Julius Caesar's legacy of 44 BC, by which he was officially adopted as Caesar's only son and the sole legitimate heir of his enormous wealth. Antony had been the most important and most successful senior officer in Caesar's army (magister equitum) and, thanks to his military record, claimed a substantial share of the political support of Caesar's soldiers and veterans. Both Octavian and Antony had fought against their common enemies in the Liberators' civil war that followed the assassination of Caesar.

After years of loyal cooperation with Octavian, Antony started to act independently, eventually arousing his rival's suspicion that he was vying to become sole master of Rome. When he left Octavia Minor and moved to Alexandria to become Cleopatra's official partner, many Roman politicians suspected that he was trying to become the unchecked ruler of Egypt and other eastern kingdoms while still maintaining his command over the many Roman legions in the East. As a personal challenge to Octavian's prestige, Antony tried to get Caesarion accepted as a true heir of Caesar, even though the legacy did not mention him. Antony and Cleopatra formally elevated Caesarion, then 13, to power in 34 BC, giving him the title "King of the Kings" (Donations of Alexandria).[11][12] Such an entitlement was seen as a threat to Roman republican traditions. It was widely believed that Antony had once offered Caesarion a diadem. Thereafter, Octavian started a propaganda war, denouncing Antony as an enemy of Rome and asserting that he intended to establish a monarchy over the Roman Empire on Caesarion's behalf, circumventing the Roman Senate. It was also said that Antony intended to move the imperial capital to Alexandria.[13][14]

As the Second Triumvirate formally expired on the last day of 33 BC, Antony wrote to the Senate that he did not wish to be reappointed. He hoped that it might regard him as its champion against the ambition of Octavian, whom he presumed would not be willing to abandon his position in a similar manner. The causes of mutual dissatisfaction between the two had been accumulating. Antony complained that Octavian had exceeded his powers in deposing Lepidus, in taking over the countries held by Sextus Pompeius and in enlisting soldiers for himself without sending half to him. Octavian complained that Antony had no authority to be in Egypt; that his execution of Sextus Pompeius was illegal; that his treachery to the king of Armenia disgraced the Roman name; that he had not sent half the proceeds of the spoils to Rome according to his agreement; and that his connection with Cleopatra and acknowledgement of Caesarion as a legitimate son of Caesar were a degradation of his office and a menace to himself.[15]

In 32 BC, one-third of the Senate and both consuls, Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and Gaius Sosius, allied with Antony. The consuls had determined to conceal the extent of Antony's demands. Ahenobarbus seems to have wished to keep quiet, but on 1 January Sosius made an elaborate speech in favor of Antony, and would have proposed the confirmation of his act had it not been vetoed by a tribune. Octavian was not present, but at the next meeting made a reply that provoked both consuls to leave Rome to join Antony; Antony, when he heard of it, after publicly divorcing Octavia, went at once to Ephesus with Cleopatra, where a vast fleet was gathered from all parts of the East, of which Cleopatra furnished a large proportion.[15] After staying with his allies at Samos, Antony moved to Athens. His land forces, which had been in Armenia, came down to the coast of Asia and embarked under Publius Canidius Crassus.[16]

Octavian kept up his strategic preparations. Military operations began in 32 BC, when his general Agrippa captured Methone, a Greek town allied to Antony. But by the publication of Antony's will, which Lucius Munatius Plancus had put into Octavian's hands, and by carefully letting it be known in Rome what preparations were going on at Samos and how Antony was effectively acting as the agent of Cleopatra, Octavian produced such a violent outburst of feeling that he easily obtained Antony's deposition from the consulship of 31 BC, for which Antony had been designated. In addition to the deposition, Octavian procured a proclamation of war against Cleopatra. This was well understood to mean against Antony, though he was not named.[16] In issuing a war declaration, the Senate deprived Antony of any legal authority.

Battle

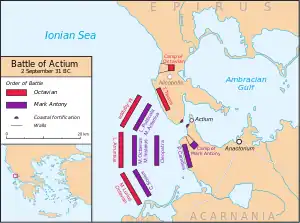

Antony initially planned to anticipate an attack by descent upon Italy toward the end of 32 BC; he went as far as Corcyra. Finding the sea guarded by a squadron of Octavian's ships, Antony retired to winter at Patrae while his fleet for the most part lay in the Ambracian Gulf, and his land forces encamped near the promontory of Actium, while the opposite side of the narrow strait into the Ambracian Gulf was protected by a tower and troops.[16]

After Octavian's proposals for a conference with Antony were scornfully rejected, both sides prepared for the struggle the next year. The early months passed without any notable events, other than some successful forays by Agrippa along the coasts of Greece, primarily designed to divert Antony's attention. In August, troops landed near Antony's camp on the north side of the strait. Still, Antony could not be tempted out. It took some months for his full strength to arrive from the various places in which his allies or his ships had wintered. During these months Agrippa continued his attacks upon Greek towns along the coast, while Octavian's forces engaged in various successful cavalry skirmishes, so that Antony abandoned the strait's north side between the Ambracian Gulf and the Ionian Sea and confined his soldiers to the southern camp. Cleopatra now advised that garrisons be put into strong towns and that the main fleet return to Alexandria. The large contingent furnished by Egypt gave her advice as much weight as her personal influence over Antony, and it appears that this movement was agreed to.[16]

Octavian learned of this and debated how to prevent it. At first of a mind to let Antony sail and then attack him, he was prevailed upon by Agrippa to give battle.[17] On 1 September he addressed his fleet, preparing them for battle. The next day was wet and the sea was rough. When the trumpet signal for the start rang out, Antony's fleet began issuing from the straits and the ships moved into line and remained quiet. Octavian, after a short hesitation, ordered his vessels to steer to the right and pass the enemy's ships. For fear of being surrounded, Antony was forced to give the word to attack.[16]

Order of battle

The two fleets met outside the Gulf of Actium on the morning of 2 September. Antony's fleet had 250 larger galleys,[16] with towers full of armed men. He led them through the straits towards the open sea. Octavian's fleet had 400 galleys.[18] His fleet was waiting beyond the straits, led by the experienced admiral Agrippa, commanding from the left wing of the fleet, Lucius Arruntius the centre[19] and Marcus Lurius the right.[20] Titus Statilius Taurus[20] commanded Octavian's armies, and observed the battle from shore to the north of the straits. Antony and Lucius Gellius Poplicola commanded the Antonian fleet's right wing, Marcus Octavius and Marcus Insteius commanded the centre, while Gaius Sosius commanded the left wing; Cleopatra's squadron was behind them. Sosius launched the initial attack from the fleet's left wing while Antony's chief lieutenant Publius Canidius Crassus commanded the triumvir's land forces.[20]

Pelling notes that the presence of two former consuls on Antony's side commanding the wings indicates that it was there that the major action was expected to take place. Octavius and Insteius, commanding Antony's centre, were lower-profile figures.[21]

Combat

It is estimated that Antony had around 140 ships,[22] to Octavian's 260. Antony had shown up to Actium with a much larger force of around 500 ships, but could not man all of them. The problem facing Antony was desertion. Plutarch and Dio speak of how desertion and disease plagued Antony's camp. What Antony lacked in quantity was made up for in quality: his ships were mainly the standard Roman warship, quinqueremes with smaller quadriremes, heavier and wider than Octavian's, making them ideal weapon platforms, however, due to their larger size they were less manoeuvrable than Octavian's ships.[23] Antony's personal flagship, like his admirals', was a "ten". An "eight" war galley had around 200 heavy marines, archers and at least six ballista catapults. Larger than Octavian's ships, Antony's war galleys were very difficult to board in close combat and his troops were able to rain missiles onto smaller and lower ships. The harpax, Agrippa's device made for grappling and boarding enemy ships, made this task a bit easier. The galleys' bows were armoured with bronze plates and square-cut timbers, making a successful ramming attack with similar equipment difficult. The only way to disable such a ship was to smash its oars, rendering it immobile and isolated from the rest of its fleet. Antony's ships' main weakness was lack of manoeuvrability; such a ship, once isolated from its fleet, could be swamped with boarding attacks. Also, many of his ships were undermanned with rowing crews; there had been a severe malaria outbreak while they were waiting for Octavian's fleet to arrive.[24]

Octavian's fleet was largely made up of smaller "Liburnian" vessels.[16] His ships, though smaller, were still manageable in the heavy surf and could outmanoeuvre Antony's ships, get in close, attack the above-deck crew with arrows and ballista-launched stones, and retreat.[25] Moreover, his crews were better-trained, professional, well-fed and rested. A medium ballista could penetrate the sides of most warships at close range and had an effective range of around 200 yards. Most ballistas were aimed at the marines on the ships' fighting decks.

Before the battle one of Antony's generals, Quintus Dellius, defected to Octavian, bringing with him Antony's battle plans.[26]

Shortly after midday, Antony was forced to extend his line from the protection of the shore and finally engage the enemy. Seeing this, Octavian's fleet put to sea. Antony had hoped to use his biggest ships to drive back Agrippa's wing on the north end of his line, but Octavian's entire fleet, aware of this strategy, stayed out of range. By about noon the fleets were in formation but Octavian refused to be drawn out, so Antony was forced to attack. The battle raged all afternoon without decisive result.

Cleopatra's fleet, in the rear, retreated to the open sea without engaging. A breeze sprang up in the right direction and the Egyptian ships were soon out of sight.[16] Lange argues that Antony would have had victory within reach were it not for Cleopatra's retreat.[27]

Antony had not observed the signal, and believing that it was mere panic and all was lost, followed the fleeing squadron. The contagion spread fast; everywhere sails unfurled and towers and other heavy fighting gear went by the board. Some fought on, and only long after nightfall, when many a ship was blazing from the firebrands thrown upon them, was the work done.[16] Making the best of the situation, Antony burned the ships he could no longer man while clustering the remainder tightly together. With many oarsmen dead or unfit to serve, the powerful, head-on ramming tactic for which the Octaries had been designed was now impossible. Antony transferred to a smaller vessel with his flag and managed to escape, taking a few ships with him as an escort to help break through Octavian's lines. Those left behind were captured or sunk.

J. M. Carter gives a differing account of the battle. He postulates that Antony knew he was surrounded and had nowhere to run. To turn this to his advantage, he gathered his ships around him in a quasi-horseshoe formation, staying close to the shore for safety. Then, should Octavian's ships approach his, the sea would push them into the shore. Antony foresaw that he would not be able to defeat Octavian's forces, so he and Cleopatra stayed in the rear of the formation. Eventually Antony sent the ships on the northern part of the formation to attack. He had them move out to the north, spreading out Octavian's ships, which until this point were tightly arranged. He sent Sosius to spread the remaining ships to the south. This left a hole in the middle of Octavian's formation. Antony seized the opportunity and, with Cleopatra on her ship and him on a different ship, sped through the gap and escaped, abandoning his entire force.

With the end of the battle, Octavian exerted himself to save the crews of the burning vessels and spent the whole night on board. The next day, as much of the land army had not escaped to their own lands, submitted, or were followed in their retreat to Macedonia and forced to surrender, Antony's camp was occupied, bringing an end to the war.[16]

Alternative theories

Scientists researching the "dead water" phenomenon are investigating whether the Egyptian fleet may have been trapped in dead water, which can substantially reduce the speed of a ship.[28][29]

Aftermath

The battle had extensive political consequences. Under cover of darkness some 19 legions and 12,000 cavalry fled before Antony was able to engage Octavian in a land battle. Thus, after Antony lost his fleet, his army, which had been equal to Octavian's, deserted. Though he had not laid down his imperium, Antony was a fugitive and a rebel without that shadow of a legal position the presence of the consuls and senators had given him in the previous year. Some of the victorious fleet went in pursuit of him, but Octavian visited Greece and Asia and spent the winter at Samos, though he had to briefly visit Brundisium to settle a mutiny and arrange for assignations of land.[16]

At Samos Octavian received a message from Cleopatra with the present of a gold crown and throne, offering to abdicate in favor of her sons. She was allowed to believe that she would be well treated, for Octavian was anxious to secure her for his triumph. Antony, who had found himself generally deserted, after vainly attempting to secure the army stationed near Paraetonium under Pinarius and sending his eldest son Antyllus with money to Octavian and an offer to live at Athens as a private citizen, found himself in the spring attacked on two sides. Cornelius Gallus was advancing from Paraetonium and Octavian landed at Pelusium, with the connivance, it was believed, of Cleopatra. Antony was defeated by Gallus and, returning to Egypt, advanced on Pelusium.

Despite a minor victory at Alexandria on 31 July 30 BC, more of Antony's men deserted, leaving him with insufficient forces to fight Octavian. A slight success over Octavian's tired soldiers encouraged him to make a general attack, in which he was decisively beaten. Failing to escape by ship, he stabbed himself in the stomach upon mistakenly believing false rumours propagated by Cleopatra claiming that she had committed suicide.[33] He did not die at once, and when he found out that Cleopatra was still alive, he insisted on being taken to the mausoleum where she was hiding and died in her arms. She was soon brought to the palace and vainly attempted to move Octavian to pity.[16]

Cleopatra killed herself on 12 August 30 BC. Most accounts say she put an end to her life by the bite of an asp conveyed to her in a basket of figs.[16] Octavian had Caesarion killed later that month, finally securing his legacy as Caesar's only 'son', while sparing Cleopatra's children by Antony, with the exception of Antony's older son.[34][35] Octavian admired the bravery of Cleopatra and gave her and Antony a public military funeral in Rome. The funeral was grand and a few of Antony's legions marched alongside the tomb. A day of mourning throughout Rome was enacted. This was partly due to Octavian's respect for Antony and partly because it further helped show the Roman people how benevolent Octavian was. Octavian had previously shown little mercy to surrendered enemies and acted in ways that had proven unpopular with the Roman people, yet he was given credit for pardoning many of his opponents after the Battle of Actium.[36] Further, after the battle, upon Octavian's return to Rome he celebrated his triple triumph spread over three days: the first for his victory over Illyria, the second for the Battle of Actium, and the third for his conquest of Egypt.

Octavian's victory at Actium gave him sole, uncontested control of "Mare Nostrum" ("Our Sea", i.e., the Roman Mediterranean) and he became "Augustus Caesar" and the "first citizen" of Rome. The victory, consolidating his power over every Roman institution, marked Rome's transition from republic to empire. Egypt's surrender after Cleopatra's death marked the demise of both the Hellenistic Period and the Ptolemaic Kingdom,[37] turning it into a Roman province.

To commemorate his victory, Octavian founded the nearby city of Nicopolis ("City of Victory") in 29 BC on the southernmost promontory of Epirus, opposite Actium at the mouth of the Ambracian Gulf.[38] On a hill just north of the new city, at the site where he had made his camp in 31 BC, he constructed a victory monument decorated with the bronze rostra (rams) taken from the captured warships of Antony's fleet.[39]

Notes

- Lendering, Jona (10 October 2020). "Actium (31 BCE)". Livius.org. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Kellum, Barbara (September 2010). "Representations and Re-presentations of the Battle of Actium". Oxford Scholarship Online. pp. 187–203. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195389579.003.0012. ISBN 978-0-19-538957-9. Retrieved 16 October 2020. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195389579.003.0012

- Migiro, Geoffrey (31 December 2017). "What Was the Battle of Actium?". WorldAtlas. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Eck (2003), 37.

- Eck (2003), 38.

- Eck (2003), 38–39.

- Davis, Paul K. (1999). 100 decisive battles: From ancient times to the present. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0195143669. OCLC 45102987.

- White Singer, Mary (1947). "Octavia's Mediation at Tarentum". The Classical Journal. 43 (3): 174–175. JSTOR 3293735 – via JSTOR.

- Roller, Duane W. (2010). Cleopatra: A Biography. US: Oxford University Press. pp. 70–73.

- Fowler, Paul; Grocock, Christopher; Melville, James (2017). OCR Ancient History GCSE Component 2 : Rome. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-350-01520-3. OCLC 999629260.

- David & David 2002, p. 35.

- Kebric 2005, p. 109.

- Potter 2009, p. 161.

- Scullard 2013, p. 150.

- Shuckburgh 1917, pp. 775–79.

- Shuckburgh 1917, pp. 780–84.

- Dio Cassius 50.31.

- Shuckburgh 1917, p. 781.

- Plutarch, Antony 65–66.

- Velleius Paterculus, History of Rome, ii.85.

- Pelling 1988, p. 281.

- Shuckburgh 1917, pp. 780–84, says 500.

- Plutarch, Antony 61.

- Dio Cassius 50.13.

- Dio Cassius 50.32.

- Dio Cassius 50.23.1–3.

- Lange, Carsten (December 2011). "The Battle of Actium: A reconsideration". Classical Quarterly. New Series, 61 (2): 608–623. doi:10.1017/S0009838811000139. JSTOR 41301557. S2CID 171027512. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- CNRS (6 July 2020). "Behind the dead-water phenomenon". phys.org. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- "Scientists find clue to mysterious 'dead water' effect that stops a ship". The Week. July 15, 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- Raia, Ann R.; Sebesta, Judith Lynn (September 2017). "The World of State". College of New Rochelle. Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Lippold, Georg (1936). Die Skulpturen des Vaticanischen Museums (in German). Vol. 3. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co. pp. 169–71.

- Curtius, L. (1933). "Ikonographische Beitrage zum Portrar der romischen Republik und der Julisch-Claudischen Familie". RM (in German). 48: 184 ff. Abb. 3 Taf. 25–27.

- Plutarch, Antony 76.

- Green (1990), 697.

- Scullard (1982), 171.

- Eck (2003), 49.

- Actium – the solution Archived March 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Chronicon of Jerome, 2005 online edition (tertullian.org)

- Dio Cassius 51.1; Suetonius, Augustus 18.2; Murray and Petsas (1989).

References

- Carter, John M. (1970). The Battle of Actium: The Rise & Triumph of Augustus Caesar. Hamilton. ISBN 0241015162. OCLC 77602.

- David, Rosalie; David, Anthony E. (2002). A Biographical Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135377045.

- Everitt, Anthony (2006), Augustus: The Life of Rome's First Emperor, New York: Random House, ISBN 1-4000-6128-8

- Kebric, Robert B. (2005). Roman People. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0072869040.

- Pelling, C.B.R., ed. (1988). Plutarch: Life of Antony. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24066-2.

- Murray, William M.; Petsas, Photios M. (1989). Octavian's Campsite Memorial for the Actian War. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. Vol. 79. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

- Potter, D.S. (2009). Rome in the Ancient World: From Romulus to Justinian. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0500251522.

- Scullard, H. H. (2013). From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome 133 BC to AD 68. Routledge. ISBN 978-1136783876.

Attribution:

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Shuckburgh, Evelyn Shirley (1917). A History of Rome to the Battle of Actium. New York: Macmillan and Company.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Shuckburgh, Evelyn Shirley (1917). A History of Rome to the Battle of Actium. New York: Macmillan and Company.

Further reading

- Military Heritage published a feature about the Battle of Actium (Joseph M. Horodyski, August 2005, Volume 7, No. 1, pp. 58–63, 78), ISSN 1524-8666.

- Califf, David J. (2004). Battle of Actium. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0791074404. OCLC 52312409.

- Green, Peter (1990). Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age. University of California Press. ISBN 0520056116. OCLC 13332042.

- Gurval, Robert Alan (1995). Actium and Augustus: The Politics and Emotions of Civil War. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472105906. OCLC 32093780.

- Sheppard, Si (2009). Actium 31 BC: Downfall of Antony and Cleopatra (PDF). Oxford: Osprey Publishing (published 2009-06-10). ISBN 978-1-84603-405-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-23.

| Library resources about Battle of Actium |