Death of Cleopatra

The death of Cleopatra VII, the last ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt, occurred on either 10 or 12 August, 30 BC, in Alexandria, when she was 39 years old. According to popular belief, Cleopatra killed herself by allowing an asp (Egyptian cobra) to bite her, but for the Roman-era writers Strabo, Plutarch, and Cassius Dio, Cleopatra poisoned herself using either a toxic ointment or by introducing the poison with a sharp implement such as a hairpin. Modern scholars debate the validity of ancient reports involving snakebites as the cause of death and if she was murdered or not. Some academics hypothesize that her Roman political rival Octavian forced her to kill herself in a manner of her choosing. The location of Cleopatra's tomb is unknown. It was recorded that Octavian allowed for her and her husband, the Roman politician and general Mark Antony, who stabbed himself with a sword, to be buried together properly.

|

| Part of a series on |

| Cleopatra VII |

|---|

|

|

Cleopatra's death effectively ended the final war of the Roman Republic between the remaining triumvirs Octavian and Antony, in which Cleopatra aligned herself with Antony, father to three of her children. Antony and Cleopatra fled to Egypt following their loss at the 31 BC Battle of Actium in Roman Greece, after which Octavian invaded Egypt and defeated their forces. Committing suicide allowed her to avoid the humiliation of being paraded as a prisoner in a Roman triumph celebrating the military victories of Octavian, who would become Rome's first emperor in 27 BC and be known as Augustus. Octavian had Cleopatra's son Caesarion (also known as Ptolemy XV), rival heir of Julius Caesar, killed in Egypt but spared her children with Antony and brought them to Rome. Cleopatra's death marked the end of the Hellenistic period and Ptolemaic rule of Egypt, as well as the beginning of Roman Egypt, which became a province of the Roman Empire.[note 1]

The death of Cleopatra has been depicted in various works of art throughout history. These include the visual, literary, and performance arts, ranging from sculptures and paintings to poetry and plays, as well as modern films. Cleopatra featured prominently in the prose and poetry of ancient Latin literature. While surviving ancient Roman depictions of her death in visual arts are rare, Medieval, Renaissance, Baroque, and Modern works are numerous. Ancient Greco-Roman sculptures such as the Esquiline Venus and Sleeping Ariadne served as inspirations for later artworks portraying her death, universally involving the snakebite of an asp. Cleopatra's death has evoked themes of eroticism and sexuality in works that include paintings, plays, and films, especially from the Victorian era. Modern works depicting Cleopatra's death include Neoclassical sculpture, Orientalist painting, and cinema.

Prelude

Following the First Triumvirate and assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BC, the Roman statesmen Octavian, Mark Antony, and Aemilius Lepidus were elected as triumvirs to bring Caesar's assassins to justice, forming the Second Triumvirate.[4][5] With Lepidus marginalized in Africa and eventually placed under house arrest by Octavian,[6][7][8] the two remaining triumvirs divided control over the Roman world between the Greek East and Latin West, Antony taking the former and Octavian the latter.[9][10] Cleopatra VII of Ptolemaic Egypt, a pharaoh of Macedonian Greek descent who ruled from Alexandria,[11][12][13] had an extramarital affair with Julius Caesar that produced a son and eventual Ptolemaic co-ruler Caesarion.[14][15][16] After Caesar's death she developed a relationship with Antony.[9][17][18]

With encouragement from Cleopatra, Antony officially divorced Octavian's sister Octavia Minor in 32 BC.[19][20][21] It is likely he had already married Cleopatra during the Donations of Alexandria in 34 BC.[22][21][note 2] Antony's divorce from Octavia, Octavian's public revelation of Antony's will outlining Cleopatra's ambitions for Roman territory in the Donations of Alexandria and her continued illegal military support for a Roman citizen currently without an elected office convinced the Roman Senate, now under Octavian's control,[23][24][25] to declare war on Cleopatra.[26][27][28]

Following their defeat in the naval Battle of Actium at the Ambracian Gulf of Greece in 31 BC, Cleopatra and Antony retreated to Egypt to recuperate and prepare for an assault by Octavian, whose forces grew larger with the surrender of many of Antony's officers and soldiers in Greece.[29][30][31][note 3] After a long period of failed negotiations, Octavian's forces invaded Egypt early in 30 BC.[32][33] While Octavian captured Pelousion near the eastern borders of Ptolemaic Egypt, his officer Cornelius Gallus marched from Cyrene and captured Paraitonion to the west.[34][35] Although Antony scored a small victory over Octavian's worn out troops as they approached Alexandria's hippodrome on 1 August, 30 BC, his naval fleet and cavalry defected soon afterward.[34][31][36]

Suicide of Antony and Cleopatra

With Octavian's forces in Alexandria, Cleopatra withdrew to her tomb[note 4] with her closest attendants and had a message sent to Antony that she had died by suicide. Antony ordered his slave Eros to kill him, but instead, Eros killed himself with his sword.[39][40] In despair, Antony stabbed himself through the stomach with a sword, inflicting a fatal wound.[34][31][41] In Plutarch's telling, Antony was still alive as he was carried into Cleopatra's tomb, telling her in his dying words that he would die honorably and that she could trust a certain Gaius Proculeius on Octavian's side to treat her well.[34][42][43] The same Proculeius used a ladder to breach a window of Cleopatra's tomb and detain her inside before she could have a chance to burn herself to death along with her vast treasure.[34][44] Cleopatra was allowed to embalm Antony's body before she was forcefully escorted to the palace, where she eventually met with Octavian, who had also detained three of her children: Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene II, and Ptolemy Philadelphus.[41][45][46]

As related by Livy, in her meeting with Octavian, Cleopatra told him candidly, "I will not be led in a triumph" (Ancient Greek: οὐ θριαμβεύσομαι, romanized: ou thriambéusomai), but Octavian only gave the cryptic answer that her life would be spared.[47][48] He did not offer her any specific details about his plans for Egypt or her royal family.[49] After a spy informed Cleopatra that Octavian intended to bring her back to Rome to be paraded as a prisoner in his triumph, she avoided this humiliation by taking her own life.[31][50][51][note 5] Plutarch elaborates on how Cleopatra approached her suicide in an almost ritual process that involved bathing and then having a fine meal including figs brought to her in a basket.[52][53][54]

Plutarch writes that Octavian ordered his freedman Epaphroditus to guard her and prevent a suicide attempt, but Cleopatra and her handmaidens were able to deceive him and kill themselves nonetheless.[55] When Octavian received a note from Cleopatra requesting that she be buried next to Antony, he had his messengers rush to her. The servant broke down her door but was too late.[52] Plutarch states that she was found with her handmaiden, Iras, dying at her feet and Charmion adjusting Cleopatra's diadem before she herself fell.[52][56][57][note 6] It is unclear from primary sources if their suicides took place within the palace or inside Cleopatra's tomb.[50] Cassius Dio claims that Octavian called on trained snake charmers of the Psylli tribe of Ancient Libya to attempt an oral venom extraction and revival of Cleopatra, but their efforts failed.[58][59] Although Octavian was outraged by these events and "was robbed of the full splendor of his victory" according to Cassius Dio,[59] he had Cleopatra interred next to Antony in their tomb as requested, and also gave Iras and Charmion proper burials.[52][60][54]

Date of death

There are no surviving records indicating an exact date of Cleopatra's death.[61] Theodore Cressy Skeat deduced that she died on 12 August 30 BC, on the basis of contemporary records of fixed events along with cross examination of historical sources.[61] His supposition is supported by Stanley M. Burstein,[41] James Grout,[58] and Aidan Dodson and Dyan Hilton, although the latter are more cautious by qualifying it was circa 12 August.[62] An alternative date of 10 August 30 BC is supported by scholars such as Duane W. Roller,[50] Joann Fletcher,[63] and Jaynie Anderson.[53]

Cause of death

Cleopatra's personal physician Olympos, cited by Plutarch, mentioned neither a cause of death nor an asp bite or Egyptian cobra.[67][note 7] Strabo, who provides the earliest known historical account, believed that Cleopatra committed suicide either by asp bite or poisonous ointment.[53][68][69][note 8] Plutarch mentions the tale of the asp brought to her in a basket of figs, although he offers other alternatives for her cause of death, such as use of a hollow implement (Greek: κνηστίς, romanized: knestis), perhaps a hairpin,[54] which she used to scratch open the skin and introduce the toxin.[67] According to Cassius Dio small puncture wounds were found on Cleopatra's arm, but he echoed the claim by Plutarch that nobody knew the true cause of her death.[70][67][58] Dio mentioned the claim of the asp and even suggested use of a needle (Greek: βελόνη, romanized: belone), possibly from a hairpin, which would seem to corroborate Plutarch's account.[70][67][58] Other contemporary historians such as Florus and Velleius Paterculus supported the asp bite version.[71][72] Roman physician Galen mentioned the asp story,[72] but he advances a version where Cleopatra bit her own arm and introduced venom brought in a container.[73] Suetonius relayed the story of the asp but expressed doubt about its validity.[72]

The cause of Cleopatra's death was rarely mentioned and debated in early modern scholarship.[74] The encyclopedic writer Thomas Browne, in his 1646 Pseudodoxia Epidemica, explained that it was uncertain how Cleopatra had died and that artistic depictions of small snakes biting her failed to accurately show the large size of the "land asp".[75] In 1717 the anatomist Giovanni Battista Morgagni maintained a brief, recreational literary correspondence with the papal physician Giovanni Maria Lancisi about the queen's cause of death, as referenced in Morgagni's 1761 De Sedibus and published as a series of epistles in his 1764 Opera omnia.[76] Morgagni argued that Cleopatra was likely killed by a snakebite and contested Lancisi's suggestion that consumption of venom was more plausible, noting that no ancient Greco-Roman authors had mentioned her drinking it. Lancisi rebutted by arguing that accounts offered by Roman poets were unreliable since they often exaggerated events.[77] In his literary memoirs published in 1777, the physician Jean Goulin supported Morgagni's argument of the snakebite being the most probable cause of death.[78]

Modern scholars have also cast doubt on the story of the venomous snakebite as the cause of death. Roller notes the prominence of snakes in Egyptian mythology while also asserting that no surviving historical account discusses the difficulty of smuggling a large Egyptian cobra into Cleopatra's chambers and then having it behave as intended.[67] Roller also claims the venom is only fatal if injected into a vital area of the body.[67] Egyptologist Wilhelm Spiegelberg (1870–1930) argued that Cleopatra's choice of suicide by asp bite was one that befitted her royal status, the asp representing the uraeus, sacred serpent of the ancient Egyptian sun god Ra.[79] Robert A. Gurval, Associate Professor of Classics at UCLA, points out that the Athenian strategos Demetrios of Phaleron (c. 350 – c. 280 BC), confined by Ptolemy II Philadelphus in Egypt, committed suicide by asp bite in a "curiously similar" manner, one that also demonstrated that it was not exclusive to Egyptian royalty.[80][note 9] Gurval notes that the bite of an Egyptian cobra contains around 175–300 mg of neurotoxin, lethal to humans with only 15–20 mg, although death would not have been immediate as victims usually stay alive for several hours.[81] François Pieter Retief, retired lecturer and dean of medicine at the University of the Free State, and Louise Cilliers, honorary research fellow at their Department of Greek, Latin and Classical Studies, argue that a large snake would not have fit into a basket of figs and it was more likely that poisoning would have so rapidly killed the three adult women, Cleopatra and her handmaidens Charmion and Iras.[82] Noting the example of Cleopatra's hairpin, Cilliers and Retief also highlight how other ancient figures poisoned themselves in similar ways, including Demosthenes, Hannibal, and Mithridates VI of Pontus.[83]

According to Gregory Tsoucalas, lecturer in the history of medicine at the Democritus University of Thrace, and Markos Sgantzos, Associate Professor of Anatomy at the University of Thessaly, evidence suggests that Octavian ordered the poisoning of Cleopatra.[84] In Murder of Cleopatra, the criminal profiler Pat Brown argues that Cleopatra was murdered and the details of it were covered up by Roman authorities.[85] Claims that she was murdered contradict the majority of primary sources that report her cause of death as suicide.[86] Historian Patricia Southern speculates that Octavian could have possibly allowed Cleopatra to choose the manner of her death instead of executing her.[39] Grout writes that Octavian may have wanted to avoid the sort of sympathy espoused for Cleopatra's younger sister Arsinoe IV when she was paraded in chains but spared during Julius Caesar's triumph.[58] Octavian perhaps permitted Cleopatra to die by her own hand after considering the political issues that could have risen from the murder of a queen whose statue had been erected in the Temple of Venus Genetrix by his adoptive father.[58] An alternative theory emerged in 1888 when Ambroise Viaud Grand Marais suggested Cleopatra had died of carbon monoxide poisoning.[87]

Aftermath

During her final days, Cleopatra had Caesarion sent away to Upper Egypt and perhaps planned for him to eventually flee to Nubia, Ethiopia, or India in exile.[72][90][35] Caesarion reigned as Ptolemy XV for only eighteen days, when he was captured and executed on Octavian's orders on 29 August, 30 BC.[91][92] This was done following the advice of the Alexandrian Greek philosopher Arius Didymus, who cautioned that two rival heirs to Julius Caesar could not share the world together.[91][92]

The deaths of Cleopatra and Caesarion marked the end of both the Ptolemaic dynasty's rule of Egypt and the Hellenistic period,[93][94][95] which had lasted since the reign of Alexander the Great (r. 336–323 BC).[note 1] Egypt became a province of the newly established Roman Empire, with Octavian renamed in 27 BC as Augustus, the first Roman emperor,[93][94][95][note 10] ruling with the facade of a Roman Republic.[96] Roller affirms that Caesarion's alleged reign was "essentially a fiction" invented by chroniclers of Egypt, such as Clement of Alexandria in his Stromata, to explain the gap between Cleopatra's death and the induction of Egypt as a Roman province directly ruled by Octavian as pharaoh of Egypt.[97][note 11] Antony's three children with Cleopatra were spared and sent to Rome; their daughter Cleopatra Selene II eventually married Juba II of Mauretania.[46][98][99]

Tomb of Antony and Cleopatra

The site of the mausoleum of Cleopatra and Mark Antony is uncertain.[46] The Egyptian Antiquities Service believes that it is in or near a temple of Taposiris Magna, southwest of Alexandria.[101][102] In their excavations of the temple of Osiris at Taposiris Magna, archaeologists Kathleen Martinez and Zahi Hawass have discovered six burial chambers and their artifacts, including forty coins minted by Cleopatra and Antony as well as an alabaster bust depicting Cleopatra.[103] An alabaster mask with a cleft chin discovered at the site bears a resemblance to ancient portraits of Mark Antony.[104] In an early 1st century AD painting from the House of Giuseppe II in Pompeii, a rear wall depicted with a set of double doors positioned very high above the scene of a woman wearing a royal diadem and committing suicide among her attendants suggests the described layout of Cleopatra's tomb in Alexandria.[1]

Depictions in art and literature

Hellenistic and Roman eras

.jpg.webp)

In his triumphant procession at Rome in 29 BC, Octavian paraded Cleopatra's children Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene II, but he also presented an effigy to the crowd depicting Cleopatra with an asp clinging to her.[105][53][106] This was likely the same painting discovered in emperor Hadrian's Villa in 1818, now lost but described in an archaeological report and depicted in a steel engraving by John Sartain.[64][65] The poet Propertius, an eyewitness of Octavian's triumph along the Via Sacra, noted that the paraded image of Cleopatra contained multiple snakes biting each of her arms.[81][107] Citing Plutarch, Giuseppe Pucci indicates that the effigy may have even been a statue.[108] In his "Notes isiaques I" (1989), French Archaeologist Jean-Claude Grenier observed that an ancient Roman statue of a woman wearing a knot of Isis in the Vatican Museums portrays a snake crawling up her right breast, perhaps a depiction of Cleopatra's suicide while dressed as the Egyptian goddess Isis.[109] Cleopatra's association with Isis continued in Egypt after her death, at least until 373 AD, when the Egyptian scribe Petesenufe compiled a book of Isis and explained how he decorated images of Cleopatra with gold.[110]

A mid-1st century BC Roman wall painting from Pompeii most likely depicting Cleopatra with her infant son Caesarion was walled off by its owner around 30 BC, perhaps in reaction to Octavian's proscription against images depicting Caesarion, the rival heir of Julius Caesar.[88][89] Although statues of Mark Antony were torn down, those of Cleopatra were generally spared this program of destruction, including the one erected by Caesar in the Temple of Venus Genetrix in the Forum of Caesar.[111][112] An early 1st century AD painting from Pompeii most likely depicts the suicide of Cleopatra, accompanied by attendants and even her son Caesarion wearing a royal diadem like his mother, although an asp is absent from the scene, perhaps reflecting the different causes of death provided in Roman historiography.[113][2][note 13] Some posthumous images of Cleopatra meant for common consumption were perhaps less flattering. A Roman terracotta lamp in the British Museum made c. 40–80 AD contains a relief depicting a nude woman with the queen's distinct hairstyle. In it she holds a palm branch, rides an Egyptian crocodile and sits on a large phallus in a Nilotic scene.[114]

A Roman cameo glass vessel in the British Museum known as the Portland Vase contains a possible depiction of Cleopatra and her imminent death.[115] Dated to the reign of Augustus, it depicts various other figures often identified as Augustus, his sister Octavia Minor, Mark Antony and his alleged ancestor Anton. The seated woman identified as Cleopatra grasps and pulls Antony toward her while a serpent rises from between her legs and the Greek god of love Eros (Cupid) floats above them.[116]

The story of the asp was widely accepted among the Augustan-period Latin poets such as Horace and Virgil, in which two snakes were even suggested as biting Cleopatra.[53][117][118] Although retaining the negative views of Cleopatra apparent in other pro-Augustan Roman literature,[119] Horace depicted Cleopatra's suicide as a bold act of defiance and liberation.[120] Virgil established the view of Cleopatra as a figure of epic melodrama and romance.[121]

Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque periods

The story of Cleopatra's suicide by snakebite was often depicted in Medieval and Renaissance art. The artist known as the Boucicaut Master, in a 1409 AD miniature for an illuminated manuscript of Des cas de nobles hommes et femmes by the 14th-century AD poet Giovanni Boccaccio, depicted Cleopatra and Antony lying together in a Gothic-style tomb, with a snake near Cleopatra's chest and a bloody sword driven through Antony's chest.[122] Illustrated versions of Boccaccio's written works, including images of Cleopatra and Antony committing suicide, first appeared in France during the Quattrocento (i.e. 15th century AD), authored by Laurent de Premierfait.[124] Woodcut illustrations of Boccaccio's De Mulieribus Claris published at Ulm in 1479 and Augsburg in 1541 depict Cleopatra's discovery of Antony's body after his suicide by stabbing.[125]

Like much of Medieval literature about Cleopatra, Boccaccio's writings are largely negative and misogynistic. The 14th-century poet Geoffrey Chaucer counters these depictions, offering a positive view of Cleopatra.[126] Chaucer began his hagiography on virtuous pagan women with the life of Cleopatra, depicted in a satirical fashion as a queen engaged in courtly love with her knight Mark Antony.[127][128] His depiction of her suicide included a pit of serpents rather than the Roman tale of the asps.[129][130]

Free-standing nude depictions of Cleopatra poisoned by an asp became common during the Italian Renaissance.[131] The 16th-century Venetian artist Giovanni Maria Padovano (i.e. Mosca) created two marble reliefs of the suicide of Antony and Cleopatra, as well as several free-standing nude statues of Cleopatra being bitten by the asp that were partly inspired by ancient Roman sculptures such as the Esquiline Venus.[132][note 14] Bartolommeo Bandinelli created a drawing of Cleopatra as a free-standing nude committing suicide that served as the basis for a similar engraving by Agostino Veneziano.[131] Another engraving by Veneziano and a drawing by Raphael depicting Cleopatra's suicide as she slumbered were inspired by the ancient Greco-Roman Sleeping Ariadne, which at the time was thought to depict Cleopatra.[133][134] Works of the French Renaissance also depict Cleopatra slumbering while pressing a snake to her breast.[135] Michelangelo created a black-chalk drawing of Cleopatra's suicide by asp bite around 1535.[136] The 17th-century Baroque painter Guido Reni depicted Cleopatra's death by asp bite, albeit with a snake that is tiny compared to a real Egyptian cobra.[137]

The Sleeping Ariadne, acquired by Pope Julius II in 1512, inspired three poems of Renaissance literature eventually carved into the pilaster frame of the statue.[138] The first of these was published by Baldassare Castiglione, which became widely circulated by 1530 and inspired the other two poems by Bernardino Baldi and Agostino Favoriti.[107] Castiglione's poem depicted Cleopatra as a tragic but honorable ruler in a doomed love affair with Antony, a queen whose death freed her from the ignominy of Roman imprisonment.[139] The Sleeping Ariadne was also commonly depicted in paintings, including those by Titian, Artemisia Gentileschi, and Edward Burne-Jones.[134] These works tended to eroticize the moment of Cleopatra's death, while Victorian era artists found the unconscious, recumbent female form as an acceptable outlet for their eroticism.[134]

Cleopatra's death features in several works of the performing arts. In the 1607 play Devil's Charter by Barnabe Barnes, a snake handler brings two asps to Cleopatra and allows them to bite both her breasts in a racy manner.[136] In William Shakespeare's 1609 play Antony and Cleopatra the snake represents both death as well as a lover who Cleopatra desires, yielding to his pinch.[136] Shakespeare relied on Thomas North's 1579 translation of Plutarch for crafting his play, which can be viewed as both a comedy and a tragedy.[140] The play involved use of multiple asps, as well as the character of Charmion who killed herself by asp bite after Cleopatra.[141]

Modern era

In modern literature, Ted Hughes' poem "Cleopatra to the Asp" (1960) creates a monologue of Cleopatra speaking to the asp that is about to kill her.[142] During the Victorian era, plays such as Cléopâtre (1890) by Victorien Sardou became popular, although audiences were generally shocked by the emotional intensity of stage actress Sarah Bernhardt's depiction of Cleopatra reacting to Antony's suicide.[143] In opera, Samuel Barber's Antony and Cleopatra, first performed in 1966 and based on Shakespeare's play, Cleopatra recounts a dream that Antony, now dead before her, would become emperor of Rome.[144] When Dollabella informs her that Caesar intends to march her in his triumph in Rome, she commits suicide with Charmion by asp bite, before being carried off to be buried with Antony.[145]

The 1940 poem Cleopatra by Russian poet Anna Akhmatova portrays the death, with its 12 lines ending as: "heedless hand drops short black asp upon a swarthy breast".[147]

The character of Cleopatra had appeared in forty-three films by the end of the 20th century.[148] Georges Méliès' Robbing Cleopatra's Tomb (French: Cléopâtre), an 1899 French silent horror film, was the first to depict the character of Cleopatra.[149] Following the Italo-Turkish War (1911–1912), the 1913 Italian film Marcantonio e Cleopatra by Enrico Guazzoni depicted Cleopatra as the embodiment of the cruel Orient, a queen who had defied Rome, while the actions of her lover Antony, after his suicide, are forgiven by Octavian.[150] In cultivating a stage persona for her character in the 1917 US film Cleopatra, actress Theda Bara was seen in public petting snakes while the Fox Film Corporation posed her in front of Cleopatra's alleged mummified remains in a museum, where she announced that she was the reincarnation of Cleopatra, having received hieroglyphic tributary offerings from a reincarnated servant.[151] Fox Studios also had Bara dress as a leader of the occult and associated her with perverse death and sexuality.[151] The 1963 Hollywood film Cleopatra by Joseph L. Mankiewicz contains a dramatic scene where the Egyptian queen, portrayed by Elizabeth Taylor, is engaged in a slap-fight with her lover Mark Antony, portrayed by Richard Burton, inside the tomb where they would be interred.[152]

In other modern visual arts, Cleopatra has been depicted in mediums such as paintings and sculptures. In her 1876 sculpture The Death of Cleopatra, African American artist Edmonia Lewis, despite championing the non-white female form in artworks, chose to depict Cleopatra with Caucasian features, perhaps in keeping with Cleopatra's recorded lineage as a Macedonian Greek.[146][note 15] Lewis' Neoclassical sculpture offers a post-mortem view of Cleopatra dressed in Egyptian regalia and sitting on her throne, which is decorated with two sphinx heads that represent the twins she bore with Mark Antony: Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene II.[153] An 1880 plaster sculpture of Cleopatra committing suicide, now found in Lille, France, was once thought to be a work by Albert Darcq, but restoration and cleaning of the sculpture revealed the signature of Charles Gauthier, to whom the work is now attributed.[154] The 1874 painting Death of Cleopatra by Jean-André Rixens depicts a dead Cleopatra with very light skin, accompanied by maidservants with rather dark skin, a combination frequently found in modern artworks portraying the scene of Cleopatra's death.[155] Orientalist paintings by Rixens and others influenced the hybrid Ancient-Egyptian and Middle-Eastern decor found in the J. Gordon Edwards' film Cleopatra starring Bara, seen standing on a Persian carpet but with Egyptian wall paintings in the background.[156]

Paintings

The Death of Cleopatra by Guido Cagnacci, 1658

The Death of Cleopatra by Guido Cagnacci, 1658 The Death of Cleopatra by Jean-André Rixens, 1874[58]

The Death of Cleopatra by Jean-André Rixens, 1874[58] The Death of Cleopatra by Juan Luna, 1881

The Death of Cleopatra by Juan Luna, 1881 The Death of Cleopatra by Reginald Arthur, 1892

The Death of Cleopatra by Reginald Arthur, 1892

Prints

Cleopatra, by Jan Muller, after Adriaen de Vries, c. 1598

Cleopatra, by Jan Muller, after Adriaen de Vries, c. 1598 The suicide of Cleopatra: the asp is wriggling up the left arm of the sleeping Cleopatra (after the Sleeping Ariadne), engraving by Jean-Baptiste de Poilly (1669–1728)

The suicide of Cleopatra: the asp is wriggling up the left arm of the sleeping Cleopatra (after the Sleeping Ariadne), engraving by Jean-Baptiste de Poilly (1669–1728) Cleopatra, by Robert Strange (after Guido Reni), 1777

Cleopatra, by Robert Strange (after Guido Reni), 1777

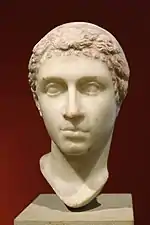

Statues, busts and other sculptures

The Esquiline Venus, 1st century AD Roman copy of a late Hellenistic artwork from the 1st century BC, with a snake depicted on the vase at the base and a woman wearing a royal diadem.[88]

The Esquiline Venus, 1st century AD Roman copy of a late Hellenistic artwork from the 1st century BC, with a snake depicted on the vase at the base and a woman wearing a royal diadem.[88] Cleopatra taking her own life with the bite of a venomous serpent, Adam Lenckhardt (1610–1661), Ivory, Walters Art Museum[157]

Cleopatra taking her own life with the bite of a venomous serpent, Adam Lenckhardt (1610–1661), Ivory, Walters Art Museum[157] Bust of Cleopatra committing suicide, by Claude Bertin (d. 1705)

Bust of Cleopatra committing suicide, by Claude Bertin (d. 1705) Cleopatra, by Charles Gauthier, 1880

Cleopatra, by Charles Gauthier, 1880

See also

Notes

- Grant 1972, pp. 5–6 notes that the Hellenistic period, beginning with the reign of Alexander the Great (336–323 BC), came to an end with the death of Cleopatra in 30 BC. Michael Grant stresses that the Hellenistic Greeks were viewed by contemporary Romans as having declined and diminished in greatness since the age of Classical Greece, an attitude that has continued even into the works of modern historiography. In regards to Hellenistic Egypt, Grant argues that "Cleopatra VII, looking back upon all that her ancestors had done during that time, was not likely to make the same mistake. But she and her contemporaries of the first century BC had another, peculiar, problem of their own. Could the 'Hellenistic Age' (which we ourselves often regard as coming to an end in about her time) still be said to exist at all, could any Greek age, now that the Romans were the dominant power? This was a question never far from Cleopatra's mind. But it is quite certain that she considered the Greek epoch to be by no means finished, and intended to do everything in her power to ensure its perpetuation."

- Roller (2010, p. 100) says that it is unclear if Antony and Cleopatra were ever truly married. Burstein (2004, pp. xxii, 29) says that the marriage publicly sealed Antony's alliance with Cleopatra and in defiance of Octavian he would divorce Octavia in 32 BC. Coins of Antony and Cleopatra depict them in the typical manner of a Hellenistic royal couple, as explained by Roller (2010, p. 100).

- For further validation, see Southern 2009, pp. 149–150 and Grout 2017.

- The tomb had been built during her lifetime, in keeping with ancient Egyptian practice.

- For further validation, see Jones 2006, p. 180 and Grout 2017.

- For primary source translations of Plutarch's account of the deaths of Charmion and Iras, see Plutarch 1920, p. 85, Grout 2017, and Jones 2006, pp. 193–194.

- Historian Duane W. Roller, in Roller 2010, pp. 148–149, provides a thorough explanation of the various claims about Cleopatra's cause of death in Roman historiography and primary sources. He states unequivocally that Olympos did not describe any cause of death, only that Plutarch discussed the cause of death only after he was finished relaying the report by Olympos, introducing the tale of the asp bite in such a way that he expected his readers to have already had foreknowledge of it.

- For further validation, see Roller 2010, p. 148.

- For further validation that Demetrios of Phaleron, adviser to Ptolemy I Soter, died from an asp bite, see Roller 2010, p. 149.

- For further validation, see Jones 2006, pp. 197–198.

- For further information, see Skeat 1953, pp. 99–100.

Plutarch, translated by Jones 2006, p. 187, wrote in vague terms that "Octavian had Caesarion killed later, after Cleopatra's death."

Contrary to regular Roman provinces, Octavian established Egypt as territory under his personal control, barring the Roman Senate from intervening in any of its affairs and appointing his own equestrian governors of Egypt, the first of whom was Cornelius Gallus. For further information, see Southern 2014, p. 185 and Roller 2010, p. 151. - Fletcher 2008, p. 87 describes the painting from Herculaneum further: "Cleopatra's hair was maintained by her highly skilled hairdresser Eiras. Although rather artificial looking wigs set in the traditional tripartite style of long straight hair would have been required for her appearances before her Egyptian subjects, a more practical option for general day-to-day wear was the no-nonsense 'melon hairdo' in which her natural hair was drawn back in sections resembling the lines on a melon and then pinned up in a bun at the back of the head. A trademark style of Arsinoe II and Berenike II, the style had fallen from fashion for almost two centuries until revived by Cleopatra; yet as both traditionalist and innovator, she wore her version without her predecessor's fine head veil. And whereas they had both been blonde like Alexander, Cleopatra may well have been a redhead, judging from the portrait of a flame-haired woman wearing the royal diadem surrounded by Egyptian motifs which has been identified as Cleopatra."

- For further information about the painting in the House of Giuseppe II (i.e. Joseph II) at Pompeii and the possible identification of Cleopatra as one of the figures, see Pucci 2011, pp. 206–207, footnote 27

- As outlined by Pina Polo 2013, pp. 186, 194 footnote 10, Roller 2010, p. 175, Anderson 2003, p. 59, scholars debate whether or not the Esquiline Venus—discovered in 1874 on the Esquiline Hill in Rome and housed in the Palazzo dei Conservatori of the Capitoline Museums—is a depiction of Cleopatra, based on the hairstyle and facial features of the woman in the sculpture, her apparent royal diadem worn over the head, and the uraeus Egyptian cobra wrapped around a vase or column at the base. As explained by Roller 2010, p. 175, the Esquiline Venus is generally thought to be a mid-1st century AD Roman copy of a 1st century BC Greek original from the school of Pasiteles.

- Pucci 2011, p. 201 affirms that "to give Cleopatra a white complexion is quite correct, given her Macedonian descent. In literature, however, Cleopatra's racial features are more ambiguous."

For Cleopatra's European origins through her ancestor Ptolemy I Soter, a general of Alexander the Great from the kingdom of Macedonia in northern Greece, see Fletcher 2008, pp. 1, 23 and Southern 2009, p. 43.

References

Citations

- Roller (2010), pp. 178–179.

- Elia (1956), pp. 3–7.

- Walker & Higgs (2001), pp. 314–315.

- Roller (2010), p. 75.

- Burstein (2004), pp. xxi, 21–22.

- Bringmann (2007), p. 301.

- Roller (2010), p. 98.

- Burstein (2004), p. 27.

- Grant & Badian (2018).

- Roller (2010), p. 76.

- Roller (2010), pp. 15–16.

- Jones (2006), pp. xiii, 3, 279.

- Southern (2009), p. 43.

- Bringmann (2007), p. 260.

- Fletcher (2008), pp. 162–163.

- Jones (2006), p. xiv.

- Roller (2010), pp. 76–84.

- Burstein (2004), pp. xxii, 25.

- Roller (2010), p. 135.

- Bringmann (2007), p. 303.

- Burstein (2004), pp. xxii, 29.

- Roller (2010), p. 100.

- Roller (2010), p. 134.

- Bringmann (2007), pp. 302–303.

- Burstein (2004), pp. 29–30.

- Roller (2010), pp. 136–137.

- Burstein (2004), pp. xxii, 30.

- Jones (2006), p. 147.

- Roller (2010), p. 140.

- Burstein (2004), pp. xxii–xxiii, 30–31.

- Bringmann (2007), p. 304.

- Burstein (2004), pp. xxiii, 31.

- Roller (2010), pp. 144–145.

- Roller (2010), p. 145.

- Southern (2009), p. 153.

- Southern (2009), pp. 153–154.

- Pina Polo (2013), pp. 184–186.

- Roller (2010), pp. 54, 174–175.

- Southern (2009), p. 154.

- Jones (2006), p. 184.

- Burstein (2004), p. 31.

- Southern (2009), pp. 154–155.

- Jones (2006), pp. 184–185.

- Jones (2006), pp. 185–186.

- Roller (2010), p. 146.

- Southern (2009), p. 155.

- Roller (2010), pp. 146–147, 213 footnote83.

- Gurval (2011), p. 61.

- Roller (2010), pp. 146–147.

- Roller (2010), pp. 147–148.

- Burstein (2004), pp. xxiii, 31–32.

- Roller (2010), p. 147.

- Anderson (2003), p. 56.

- Jones (2006), p. 194.

- Plutarch (1920), p. 79.

- Anderson (2003), pp. 56, 62.

- Gurval (2011), p. 72.

- Grout (2017).

- Jones (2006), p. 195.

- Burstein (2004), p. 65.

- Skeat (1953), pp. 98–100.

- Dodson & Hilton (2004), p. 277.

- Fletcher (2008), p. 3.

- Pratt & Fizel (1949), pp. 14–15.

- Sartain (1885), pp. 41, 44.

- Plutarch (1920), p. 54.

- Roller (2010), p. 148.

- Jones (2006), p. 197.

- Gurval (2011), p. 55.

- Jones (2006), pp. 194–195.

- Jones (2006), pp. 189–190.

- Roller (2010), p. 149.

- Jones (2006), pp. 195–197.

- Jarcho (1969), pp. 305–306.

- Jarcho (1969), p. 306.

- Jarcho (1969), pp. 299–300, 303–307.

- Jarcho (1969), pp. 303–304, 307.

- Jarcho (1969), p. 306, footnote 11.

- Gurval (2011), p. 56.

- Gurval (2011), p. 58.

- Gurval (2011), p. 60.

- Cilliers & Retief (2006), pp. 85–87.

- Cilliers & Retief (2006), p. 87.

- Tsoucalas & Sgantzos (2014), pp. 19–20.

- Nuwer (2013).

- Jones (2006), pp. 180–201.

- Hopper et al. (2021).

- Roller (2010), p. 175.

- Walker (2008), pp. 35, 42–44.

- Burstein (2004), p. 32.

- Roller (2010), pp. 149–150.

- Burstein (2004), pp. xxiii, 32.

- Burstein (2004), pp. xxiii, 1.

- Bringmann (2007), pp. 304–307.

- Roller (2010), pp. 150–151.

- Eder (2005), pp. 24–25.

- Roller (2010), pp. 149, 151, 214, footnote 103.

- Burstein (2004), pp. 32, 76–77.

- Roller (2010), pp. 153–155.

- Fletcher (2008), pp. 87, 246–247, see image plates and captions.

- BBC News.

- SBS News.

- Remezcla.

- Reuters.

- Roller (2010), pp. 149, 153.

- Burstein (2004), p. 66.

- Curran (2011), p. 116.

- Pucci (2011), p. 202.

- Pucci (2011), pp. 202–203, 207 footnote 28.

- Roller (2010), p. 151.

- Roller (2010), pp. 72, 151, 175.

- Varner (2004), p. 20.

- Roller (2010), pp. 148–149, 178–179.

- Bailey (2001), p. 337.

- Walker (2004), pp. 41–59.

- Roller (2010), p. 178.

- Roller (2010), pp. 148–149.

- Gurval (2011), pp. 61–69, 74.

- Roller (2010), pp. 8–9.

- Gurval (2011), pp. 65–66.

- Gurval (2011), pp. 66–70.

- Anderson (2003), pp. 53–54.

- Anderson (2003), p. 50.

- Anderson (2003), p. 51.

- Anderson (2003), pp. 50–52.

- Anderson (2003), pp. 51–54.

- Gurval (2011), pp. 73–74.

- Jones (2006), pp. 214–215.

- Gurval (2011), p. 74.

- Jones (2006), pp. 221–222.

- Anderson (2003), p. 60.

- Anderson (2003), pp. 56–59.

- Anderson (2003), pp. 60–61.

- Pucci (2011), p. 203.

- Anderson (2003), p. 61.

- Anderson (2003), p. 62.

- Gurval (2011), p. 59.

- Curran (2011), pp. 114–116.

- Curran (2011), pp. 116–117.

- Jones (2006), p. 223.

- Jones (2006), pp. 233–234.

- Jones (2006), pp. 303–304.

- DeMaria Smith (2011), p. 165.

- Martin (2014), pp. 16–17.

- Martin (2014), p. 17.

- Pucci (2011), pp. 201–202.

- Akhmatova.

- Pucci (2011), p. 195.

- Jones (2006), p. 325.

- Pucci (2011), pp. 203–204.

- Wyke & Montserrat (2011), p. 178.

- Wyke & Montserrat (2011), p. 190.

- Smithsonian American Art Museum.

- The Art Tribune.

- Manninen (2015), p. 221, footnote 11.

- Sully (2010), p. 53.

- Walters Art Museum.

Bibliography

Online sources

- "Cleopatra's tomb may have been found: Egypt's top archaeologist says the lost tomb of Mark Antony and Cleopatra may have been discovered". SBS News. 24 February 2015. Archived from the original on 10 December 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- "Dig 'may reveal' Cleopatra's tomb". BBC News. 15 April 2009. Retrieved 24 April 2009.

- "Cleopatra", The Walters Art Museum, retrieved 29 March 2018.

- "Inside a Dominican Archaeologist's Drama-Filled Quest to Find Cleopatra's Tomb". Remezcla.com. 24 April 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- "Restorations of 19th century sculptures in Lille", The Art Tribune, 11 February 2016, retrieved 3 May 2018.

- "The Death of Cleopatra", Smithsonian American Art Museum, retrieved 3 May 2018.

- Grant, Michael; Badian, Ernst (28 July 2018), "Mark Antony, Roman triumvir", Encyclopaedia Britannica, retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Grout, James (1 April 2017), "The Death of Cleopatra", Encyclopaedia Romana (University of Chicago), retrieved 3 May 2018.

- Nuwer, Rachel (29 March 2013), "Maybe Cleopatra Didn't Commit Suicide: Her murder, one author thinks, was covered up behind a veil of propaganda and lies put forth by the Roman Empire", Smithsonian, retrieved 3 May 2018.

- Plutarch (1920), Plutarch's Lives, translated by Bernadotte Perrin, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University), retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Rasmussen, Will (19 April 2009). "Archaeologists hunt for Cleopatra's tomb in Egypt". Reuters. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

Printed sources

- Anderson, Jaynie (2003), Tiepolo's Cleopatra, Melbourne: Macmillan, ISBN 9781876832445.

- Bailey, Donald (2001), "357 Roman terracotta lamp with a caricatured scene", in Walker, Susan; Higgs, Peter (eds.), Cleopatra of Egypt: from History to Myth, Princeton, N.J., p. 337, ISBN 9780691088358.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bringmann, Klaus (2007) [2002], A History of the Roman Republic, translated by W. J. Smyth, Cambridge: Polity Press, ISBN 9780745633718.

- Burstein, Stanley M. (2004), The Reign of Cleopatra, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, ISBN 9780313325274.

- Cilliers, L.; Retief, F. P. (1 January 2006), "The death of Cleopatra", Acta Theologica, 26 (2): 79–88, doi:10.4314/actat.v26i2.52563, ISSN 2309-9089

- Curran, Brian A (2011), "Love, Triumph, Tragedy: Cleopatra and Egypt in High Renaissance Rome", in Miles, Margaret M. (ed.), Cleopatra : a sphinx revisited, Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 96–131, ISBN 9780520243675.

- DeMaria Smith, Margaret Mary (2011), "HRH Cleopatra: the Last of the Ptolemies and the Egyptian Paintings of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema", in Miles, Margaret M. (ed.), Cleopatra : a sphinx revisited, Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 150–171, ISBN 9780520243675.

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004), The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 9780500051283.

- Eder, Walter (2005), "Augustus and the Power of Tradition", in Galinsky, Karl (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus, Cambridge Companions to the Ancient World, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 13–32, ISBN 9780521807968.

- Elia, Olga (1956) [1955], "La tradizione della morte di Cleopatra nella pittura pompeiana", Rendiconti dell'Accademia di Archeologia, Lettere e Belle Arti (in Italian), 30: 3–7, OCLC 848857115.

- Fletcher, Joann (2008), Cleopatra the Great: The Woman Behind the Legend, New York: Harper, ISBN 9780060585587.

- Grant, Michael (1972), Cleopatra, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson; Richard Clay (the Chaucer Press), ISBN 9780297995029.

- Gurval, Robert A. (2011), "Dying Like a Queen: the Story of Cleopatra and the Asp(s) in Antiquity", in Miles, Margaret M. (ed.), Cleopatra : a sphinx revisited, Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 54–77, ISBN 9780520243675.

- Hopper, Christopher P.; Zambrana, Paige N.; Goebel, Ulrich; Wollborn, Jakob (1 June 2021), "A brief history of carbon monoxide and its therapeutic origins", Nitric Oxide, 111–112: 45–63, doi:10.1016/j.niox.2021.04.001, ISSN 1089-8603, PMID 33838343, S2CID 233205099.

- Jarcho, Saul (1969), "The correspondence of Morgagni and Lancisi on the death of Cleopatra", Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 43 (4): 299–325, JSTOR 44449955, PMID 4900196.

- Jones, Prudence J. (2006), Cleopatra: a sourcebook, Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 9780806137414.

- Manninen, Alisa (2015), Royal Power and Authority in Shakespeare's Late Tragedies, Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, ISBN 9781443876223.

- Martin, Nicholas Ivor (2014), The Opera Manual, Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, ISBN 9780810888685.

- Pina Polo, Francisco (2013), "The Great Seducer: Cleopatra, Queen and Sex Symbol", in Knippschild, Silke; García Morcillo, Marta (eds.), Seduction and Power: Antiquity in the Visual and Performing Arts, London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 183–197, ISBN 9781441190659.

- Pratt, Frances; Fizel, Becca (1949), Encaustic Materials and Methods, New York: Lear, OCLC 560769.

- Pucci, Giuseppe (2011), "Every Man's Cleopatra", in Miles, Margaret M. (ed.), Cleopatra : a sphinx revisited, Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 195–207, ISBN 9780520243675.

- Roller, Duane W. (2010), Cleopatra: a biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195365535.

- Sartain, John (1885), On the Antique Painting in Encaustic of Cleopatra: Discovered in 1818, Philadelphia: George Gebbie & Co., OCLC 3806143.

- Skeat, T. C. (1953), "The Last Days of Cleopatra: A Chronological Problem", The Journal of Roman Studies, 43 (1–2): 98–100, doi:10.2307/297786, JSTOR 297786, S2CID 162835002.

- Southern, Patricia (2014) [1998], Augustus (2nd ed.), London: Routledge, ISBN 9780415628389.

- Southern, Patricia (2009) [2007], Antony and Cleopatra: The Doomed Love Affair That United Ancient Rome and Egypt, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing, ISBN 9781848683242.

- Sully, Jess (2010), "Challenging the Stereotype: the Femme-Fatale in Fin-de-Siècle Art and Early Cinema", in Hanson, Helen; O'Rawe, Catherine (eds.), The Femme Fatale: Images, Histories, Contexts, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 46–59, ISBN 9781349301447.

- Tsoucalas, Gregory; Sgantzos, Markos (2014), "The Death of Cleopatra: Suicide by Snakebite or Poisoned by Her Enemies?", in Philip Wexler (ed.), History of Toxicology and Environmental Health: Toxicology in Antiquity, vol. 1, Amsterdam: Academic Press (Elsevier), ISBN 9780128004630.

- Varner, Eric R. (2004), Mutilation and Transformation: Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 9789004135772.

- Walker, Susan (2004), The Portland Vase, British Museum Objects in Focus, British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714150222.

- Walker, Susan (2008), "Cleopatra in Pompeii?", Papers of the British School at Rome, 76: 35–46, 345–348, doi:10.1017/S0068246200000404, JSTOR 40311128.

- Walker, Susan; Higgs, Peter (2001), "Painting with a portrait of a woman in profile", in Walker, Susan; Higgs, Peter (eds.), Cleopatra of Egypt: from History to Myth, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press (British Museum Press), pp. 314–315, ISBN 9780691088358.

- Wyke, Maria; Montserrat, Dominic (2011), "Glamour Girls: Cleomania in Mass Culture", in Miles, Margaret M. (ed.), Cleopatra : a sphinx revisited, Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 172–194, ISBN 9780520243675.

Further reading

- Bradford, Ernle Dusgate Selby (2000). Cleopatra. London: Penguin Group. ISBN 9780141390147.

- Flamarion, Edith (1997). Cleopatra: The Life and Death of a Pharaoh. "Abrams Discoveries" series. Translated by Bonfante-Warren, Alexandra. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 9780810928053.

- Foss, Michael (1999). The Search for Cleopatra. New York: Arcade Publishing. ISBN 9781559705035.

- Fraser, P.M. (1985). Ptolemaic Alexandria. Vol. 1–3 (reprint ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198142782.

- Lindsay, Jack (1972). Cleopatra. New York: Coward-McCann. OCLC 671705946.

- Nardo, Don (1994). Cleopatra. San Diego, CA: Lucent Books. ISBN 9781560060239.

- Pomeroy, Sarah B. (1984). Women in Hellenistic Egypt: from Alexander to Cleopatra. New York: Schocken Books. ISBN 9780805239119.

- Southern, Pat (2000). Cleopatra. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus. ISBN 9780752414942.

- Syme, Ronald (1962) [1939]. The Roman Revolution. Oxford University Press. OCLC 404094.

- Volkmann, Hans (1958). Cleopatra: a Study in Politics and Propaganda. T.J. Cadoux, trans. New York: Sagamore Press. OCLC 899077769.

- Weigall, Arthur E. P. Brome (1914). The Life and Times of Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt. Edinburgh: Blackwood. OCLC 316294139.

External links

- Ancient Roman depictions of Cleopatra VII of Egypt, at YouTube.

- Eubanks, W. Ralph. (1 November 2010). "How History And Hollywood Got 'Cleopatra' Wrong". National Public Radio (NPR) (a book review of Cleopatra: A Life, by Stacy Schiff).

- Jarus, Owen (13 March 2014). "Cleopatra: Facts & Biography". Live Science.

- Watkins, Thayer. "The Timeline of the Life of Cleopatra Archived 2021-08-13 at the Wayback Machine." San Jose State University.

Cleopatra., a painting by Eliza Sharpe in Pictorial Album; or, Cabinet of Paintings for the year 1837, with a poetical illustration by Letitia Elizabeth Landon

Cleopatra., a painting by Eliza Sharpe in Pictorial Album; or, Cabinet of Paintings for the year 1837, with a poetical illustration by Letitia Elizabeth Landon

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

%252C_suicidio_di_cleopatra%252C_1560_ca._02.JPG.webp)