Cyrus Cylinder

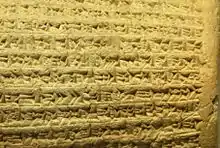

The Cyrus Cylinder is an ancient clay cylinder, now broken into several pieces, on which is written a Achaemenid royal inscription in Akkadian cuneiform script in the name of Persian king Cyrus the Great.[2][3] It dates from the 6th century BC and was discovered in the ruins of the ancient Mesopotamian city of Babylon (now in modern Iraq) in 1879.[2] It is currently in the possession of the British Museum. It was created and used as a foundation deposit following the Persian conquest of Babylon in 539 BC, when the Neo-Babylonian Empire was invaded by Cyrus and incorporated into his Persian Empire.

| Cyrus Cylinder | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) The Cyrus Cylinder, obverse and reverse sides, and transcription | |

| Material | Baked clay |

| Size | 21.9 centimetres (8.6 in) x 10 centimetres (3.9 in) (maximum) x (end A) 7.8 centimetres (3.1 in) x (end B) 7.9 centimetres (3.1 in)[1] |

| Writing | Akkadian cuneiform script |

| Created | About 539–538 BC |

| Period/culture | Achaemenid Empire[1] |

| Discovered | Babylon, Baghdad Vilayet of Ottoman Iraq, by Hormuzd Rassam in March 1879[1] |

| Present location | Room 52,[1] British Museum (London) |

| Identification | BM 90920 [1] |

| Registration | 1880,0617.1941 [1] |

The text on the Cylinder praises Cyrus, sets out his genealogy and portrays him as a king from a line of kings. The Babylonian king Nabonidus, who was defeated and deposed by Cyrus, is denounced as an impious oppressor of the people of Babylonia and his low-born origins are implicitly contrasted to Cyrus' kingly heritage. The victorious Cyrus is portrayed as having been chosen by the chief Babylonian god Marduk to restore peace and order to the Babylonians. The text states that Cyrus was welcomed by the people of Babylon as their new ruler and entered the city in peace. It appeals to Marduk to protect and help Cyrus and his son Cambyses. It extols Cyrus as a benefactor of the citizens of Babylonia who improved their lives, repatriated displaced people and restored temples and cult sanctuaries across Mesopotamia and elsewhere in the region. It concludes with a description of how Cyrus repaired the city wall of Babylon and found a similar inscription placed there by an earlier king.[3]

The Cylinder's text has traditionally been seen by biblical scholars as corroborative evidence of Cyrus' policy of the repatriation of the Jewish people following their Babylonian captivity[4] (an act that the Book of Ezra attributes to Cyrus[5]), as the text refers to the restoration of cult sanctuaries and repatriation of deported peoples.[6] This interpretation has been disputed, as the text identifies only Mesopotamian sanctuaries, and makes no mention of Jews, Jerusalem, or Judea.[7] Nonetheless, it has been seen as a sign of Cyrus's relatively enlightened approach towards cultural and religious diversity. The former Director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, said that the cylinder was "the first attempt we know about running a society, a state with different nationalities and faiths – a new kind of statecraft".[8]

In modern times, the Cylinder was adopted as a national symbol of Iran by the ruling Pahlavi dynasty, which put it on display in Tehran in 1971 to commemorate the 2,500-year celebration of the Persian Empire.[9] Princess Ashraf Pahlavi presented United Nations Secretary General U Thant with a replica of the Cylinder. The princess asserted that "the heritage of Cyrus was the heritage of human understanding, tolerance, courage, compassion and, above all, human liberty".[10] Her brother, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, promoted the Cylinder as a "charter of human rights", though this interpretation has been described by various historians as "rather anachronistic" and controversial.[11][12][13][14]

Discovery

The Assyro-British archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam discovered the Cyrus Cylinder in March 1879 during a lengthy programme of excavations in Mesopotamia carried out for the British Museum.[15] It had been placed as a foundation deposit in the foundations of the Ésagila, the city's main temple.[3] Rassam's expedition followed on from an earlier dig carried out in 1850 by the British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard, who excavated three mounds in the same area but found little of importance.[16] In 1877, Layard became Britain's ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, which ruled Mesopotamia at the time. He helped Rassam, who had been his assistant in the 1850 dig, to obtain a firman (decree) from the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II to continue the earlier excavations. The firman was only valid for a year but a second firman, with much more liberal terms, was issued in 1878. It was granted for two years (through to 15 October 1880) with the promise of an extension to 1882 if required.[17] The Sultan's decree authorised Rassam to "pack and dispatch to England any antiquities [he] found ... provided, however, there were no duplicates". A representative of the Sultan was instructed to be present at the dig to examine the objects as they were uncovered.[18]

With permission secured, Rassam initiated a large-scale excavation at Babylon and other sites on behalf of the Trustees of the British Museum.[16] He undertook the excavations in four distinct phases. In between each phase, he returned to England to bring back his finds and raise more funds for further work. The Cyrus Cylinder was found on the second of his four expeditions to Mesopotamia, which began with his departure from London on 8 October 1878. He arrived in his home town of Mosul on 16 November and travelled down the Tigris to Baghdad, which he reached on 30 January 1879. During February and March, he supervised excavations on a number of Babylonian sites, including Babylon itself.[17]

He soon uncovered a number of important buildings including the Ésagila temple, a major shrine to the chief Babylonian god Marduk, although its identity was not fully confirmed until the German archaeologist Robert Koldewey's excavation of 1900.[19] The excavators found a large number of business documents written on clay tablets buried in the temple's foundations where they discovered the Cyrus Cylinder.[16] Rassam gave conflicting accounts of where his discoveries were made. He wrote in his memoirs, Asshur and the land of Nimrod, that the Cylinder had been found in a mound at the southern end of Babylon near the village of Jumjuma or Jimjima.[20][21] However, in a letter sent on 20 November 1879 to Samuel Birch, the Keeper of Oriental Antiquities at the British Museum, he wrote, "The Cylinder of Cyrus was found at Omran [Tell Amran-ibn-Ali] with about six hundred pieces of inscribed terracottas before I left Baghdad."[22] He left Baghdad on 2 April, returning to Mosul and departing from there on 2 May for a journey to London which lasted until 19 June.[17]

The discovery was announced to the public by Sir Henry Rawlinson, the President of the Royal Asiatic Society, at a meeting of the Society on 17 November 1879.[23] He described it as "one of the most interesting historical records in the cuneiform character that has yet been brought to light", though he erroneously described it as coming from the ancient city of Borsippa rather than Babylon.[24] Rawlinson's "Notes on a newly-discovered Clay Cylinder of Cyrus the Great" were published in the society's journal the following year, including the first partial translation of the text.[25]

Description

The Cyrus Cylinder is a barrel-shaped cylinder of baked clay measuring 22.5 centimetres (8.9 in) by 10 centimetres (3.9 in) at its maximum diameter.[1] It was created in several stages around a cone-shaped core of clay within which there are large grey stone inclusions. It was built up with extra layers of clay to give it a cylindrical shape before a fine surface slip of clay was added to the outer layer, on which the text is inscribed. It was excavated in several fragments, having apparently broken apart in antiquity.[1] Today it exists in two main fragments, known as "A" and "B", which were reunited in 1972.[1]

The main body of the Cylinder, discovered by Rassam in 1879, is fragment "A". It underwent restoration in 1961, when it was re-fired and plaster filling was added.[1] The smaller fragment, "B", is a section measuring 8.6 centimetres (3.4 in) by 5.6 centimetres (2.2 in). The latter fragment was acquired by J.B. Nies[22] of Yale University from an antiquities dealer.[26] Nies published the text in 1920.[27] The fragment was apparently broken off the main body of the Cylinder during the original excavations in 1879 and was either removed from the excavations or was retrieved from one of Rassam's waste dumps. It was not confirmed as part of the Cylinder until Paul-Richard Berger of the University of Münster definitively identified it in 1970.[28] Yale University lent the fragment to the British Museum temporarily (but, in practice, indefinitely) in exchange for "a suitable cuneiform tablet" from the British Museum collection.[1]

Although the Cylinder clearly post-dates Cyrus the Great's conquest of Babylon in 539 BC, the date of its creation is unclear. It is commonly said to date to the early part of Cyrus's reign over Babylon, some time after 539 BC. The British Museum puts the Cylinder's date of origin at between 539 and 530 BC.[4]

Text

The surviving inscription on the Cyrus Cylinder consists of 45 lines of text written in Akkadian cuneiform script. The first 35 lines are on fragment "A" and the remainder are on fragment "B".[28] A number of lines at the start and end of the text are too badly damaged for more than a few words to be legible.

The text is written in an extremely formulaic style that can be divided into six distinct parts:

- Lines 1–19: an introduction reviling Nabonidus, the previous king of Babylon, and associating Cyrus with the god Marduk;

- Lines 20–22: detailing Cyrus's royal titles and genealogy, and his peaceful entry to Babylon;

- Lines 22–34: a commendation of Cyrus's policy of restoring Babylon;

- Lines 34–35: a prayer to Marduk on behalf of Cyrus and his son Cambyses;

- Lines 36–37: a declaration that Cyrus has enabled the people to live in peace and has increased the offerings made to the gods;

- Lines 38–45: details of the building activities ordered by Cyrus in Babylon.[29]

The beginning of the text is partly broken; the surviving content reprimands the character of the deposed Babylonian king Nabonidus. It lists his alleged crimes, charging him with the desecration of the temples of the gods and the imposition of forced labor upon the populace. According to the proclamation, as a result of these offenses, the god Marduk abandoned Babylon and sought a more righteous king. Marduk called forth Cyrus to enter Babylon and become its new ruler.[30]

In [Nabonidus's] mind, reverential fear of Marduk, king of the gods, came to an end. He did yet more evil to his city every day; … his [people ................…], he brought ruin on them all by a yoke without relief … [Marduk] inspected and checked all the countries, seeking for the upright king of his choice. He took the hand of Cyrus, king of the city of Anshan, and called him by his name, proclaiming him aloud for the kingship over all of everything.[30]

Midway through the text, the writer switches to a first-person narrative in the voice of Cyrus, addressing the reader directly. A list of his titles is given (in a Mesopotamian rather than Persian style): "I am Cyrus, king of the world, great king, powerful king, king of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad, king of the four quarters [of the earth], son of Cambyses, great king, king of Anshan, descendant of Teispes, great king, king of Anshan, the perpetual seed of kingship, whose reign Bel [Marduk] and Nebo love, and with whose kingship, to their joy, they concern themselves."[30] He describes the pious deeds he performed after his conquest: he restored peace to Babylon and the other cities sacred to Marduk, freeing their inhabitants from their "yoke," and he "brought relief to their dilapidated housing (thus) putting an end to their (main) complaints".[31] He repaired the ruined temples in the cities he conquered, restored their cults, and returned their sacred images as well as their former inhabitants which Nabonidus had taken to Babylon.[31] Near the end of the inscription Cyrus highlights his restoration of Babylon's city wall, saying: "I saw within it an inscription of Ashurbanipal, a king who preceded me."[30] The remainder is missing but presumably describes Cyrus's rededication of the gateway mentioned.[32]

A partial transcription by F. H. Weissbach in 1911 was supplanted by a much more complete transcription after the identification of the "B" fragment;[33] this is now available in German and in English.[34][31][35] Several editions of the full text of the Cyrus Cylinder are available online, incorporating both "A" and "B" fragments.

A false translation of the text – affirming, among other things, the abolition of slavery and the right to self-determination, a minimum wage and asylum – has been promoted on the Internet and elsewhere.[36] As well as making claims that are not found on the real cylinder, it refers to the Zoroastrian divinity Ahura Mazda rather than the Mesopotamian god Marduk.[37] The false translation has been widely circulated; alluding to its claim that Cyrus supposedly has stated that "Every country shall decide for itself whether or not it wants my leadership."[36] Iranian Nobel Peace Prize winner Shirin Ebadi in her acceptance speech described Cyrus as "the very emperor who proclaimed at the pinnacle of power 2,500 years ago that … he would not reign over the people if they did not wish it".[36][38][39]

Associated fragments

The British Museum announced in January 2010 that two inscribed clay fragments, which had been in the museum's collection since 1881, had been identified as part of a cuneiform tablet that was inscribed with the same text as the Cyrus Cylinder. The fragments had come from the small site of Dailem near Babylon and the identification was made by Professor Wilfred Lambert, formerly of the University of Birmingham, and Irving Finkel, curator in charge of the museum's Department of the Middle East.[40][41]

Relation to a Chinese bone inscription

In 1983 two fossilized horse bones inscribed with cuneiform signs surfaced in China which Professor Oliver Gurney at Oxford later identified as coming from the Cyrus Cylinder. The discovery of these objects aroused much discussion about possible connections between ancient Mesopotamia and China, although their authenticity was doubted by many scholars from the beginning and they are now generally regarded as forgeries.

The history of the putative artifact goes back almost a century.[42] The earliest record goes back to a Chinese doctor named Xue Shenwei, who sometime prior to 1928 was shown a photo of a rubbing of one of the bones by an antiquities dealer named Zhang Yi'an.[43] Although not able to view the bones at that time, Xue Shenwei later acquired one of them from another antiquities dealer named Wang Dongting in 1935 and then the second via a personal connection named Ke Yanling around 1940. While Xue did not recognize the script on the bones he guessed at its antiquity and buried the bones for safekeeping during the Cultural Revolution. Then, in 1983 Xue presented the bones to the Palace Museum in Beijing where Liu Jiuan and Wang Nanfang of the State Administration of Cultural Heritage undertook their study.[43] These officials identified the script as cuneiform and asked the Assyriologists Chi Yang and Wu Yuhong to work on the inscriptions. Identification of the source text proceeded slowly until 1985, when Wu Yuhong along with Oxford Assyriologist Stephanie Dalley and Oliver Gurney recognized the text in one bone as coming from the Cyrus Cylinder. One year later Wu Yuhong presented his findings at the 33rd Rencontre Assyriologique and published them in a journal article.[44]

After that the second bone inscription remained undeciphered until 2010, when Irving Finkel worked on it. In that same year the British Museum held a conference dedicated to the artifacts. Based on the serious textual errors in the inscription, including the omission of a large number of signs from the Cyrus Cylinder, Wu Yuhong argued the inscriptions were most likely copied from the cylinder while housed in the British Museum or from an early modern publication based upon it. However he acknowledged the remote possibility it was copied in late antiquity.[43] Irving Finkel disputed this conclusion based on the relative obscurity of the Cyrus Cylinder until recent decades and the mismatch in paleography between the bone inscriptions and the hand copies found in early editions from the 1880s.

Finally, after the workshop concluded, an 1884 edition of the Cyrus Cylinder by E. A. Wallis Budge came to Irving Finkel's attention. This publication used an idiosyncratic typeface and featured a handcopy for only a section of the whole cylinder. However the typeface in that edition matched the paleography on the bone inscriptions and the extract of the cylinder published in the book matched that of the bone as well. This convinced Finkel that the bone inscriptions were early modern forgeries and that has remained the majority opinion since then.

Interpretations

Mesopotamian and Persian tradition and propaganda

According to the British Museum, the Cyrus Cylinder reflects a long tradition in Mesopotamia where, from as early as the third millennium BC, kings began their reigns with declarations of reforms.[4] Cyrus's declaration stresses his legitimacy as the king, and is a conspicuous statement of his respect for the religious and political traditions of Babylon. The British Museum and scholars of the period describe it as an instrument of ancient Mesopotamian propaganda.[45][46]

The text is a royal building inscription, a genre which had no equivalent in Old Persian literature. It illustrates how Cyrus co-opted local traditions and symbols to legitimize his conquest and control of Babylon.[32][47] Many elements of the text were drawn from long-standing Mesopotamian themes of legitimizing rule in Babylonia: the preceding king is reprimanded and he is proclaimed to have been abandoned by the gods for his wickedness; the new king has gained power through the divine will of the gods; the new king rights the wrongs of his predecessor, addressing the welfare of the people; the sanctuaries of the gods are rebuilt or restored, offerings to the gods are made or increased and the blessings of the gods are sought; and repairs are made to the whole city, in the manner of earlier rightful kings.[3]

Both continuity and discontinuity are emphasized in the text of the Cylinder. It asserts the virtue of Cyrus as a gods-fearing king of a traditional Mesopotamian type. On the other hand, it constantly discredits Nabonidus, reviling the deposed king's deeds and even his ancestry and portraying him as an impious destroyer of his own people. As Fowler and Hekster note, this "creates a problem for a monarch who chooses to buttress his claim to legitimacy by appropriating the 'symbolic capital' of his predecessors".[48] The Cylinder's reprimand of Nabonidus also discredits Babylonian royal authority by association. It is perhaps for this reason that the Achaemenid rulers made greater use of Assyrian rather than Babylonian royal iconography and tradition in their declarations; the Cylinder refers to the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal as "my predecessor", rather than any native Babylonian ruler.[48]

The Cylinder itself is part of a continuous Mesopotamian tradition of depositing a wide variety of symbolic items, including animal sacrifices, stone tablets, terracotta cones, cylinders and figures. Newly crowned kings of Babylon would make public declarations of their own righteousness when beginning their reigns, often in the form of declarations that were deposited in the foundations of public buildings.[49] Some contained messages, while others did not, and they had a number of purposes: elaboration of a building's value, commemoration of the ruler or builder and the magical sanctification of the building, through the invocation of divine protection.

The cylinder was not intended to be seen again after its burial, but the text inscribed on it would have been used for public purposes. Archive copies were kept of important inscriptions and the Cylinder's text may likewise have been copied.[50] In January 2010, the British Museum announced that two cuneiform tablets in its collection had been found to be inscribed with the same text as that on the Cyrus Cylinder,[51] which, according to the museum, "show that the text of the Cylinder was probably a proclamation that was widely distributed across the Persian Empire".[52] A statue of the cylinder is now on exhibit in Los Angeles on the Avenue of the Stars as a gift from the Persian people to the city of Los Angeles

Similarities with other royal inscriptions

The Cyrus Cylinder bears striking similarities to older Mesopotamian royal inscriptions. Two notable examples are the Cylinder of Marduk-apla-iddina II, who seized the Babylonian throne in 722/1 BC, and the annals of Sargon II of Assyria, who conquered Babylon twelve years later. As a conqueror, Marduk-apla-iddina faced many of the same problems of legitimacy that Cyrus did when he conquered Babylon. He declares himself to have been chosen personally by Marduk, who ensured his victory. When he took power, he performed the sacred rites and restored the sacred shrines. He states that he found a royal inscription placed in the temple foundations by an earlier Babylonian king, which he left undisturbed and honored. All of these claims also appear in Cyrus's Cylinder. Twelve years later, the Assyrian king Sargon II defeated and exiled Marduk-apla-iddina, taking up the kingship of Babylonia. Sargon's annals describe how he took on the duties of a Babylonian sovereign, honouring the gods, maintaining their temples and respecting and upholding the privileges of the urban elite. Again, Cyrus's Cylinder makes exactly the same points. Nabonidus, Cyrus's deposed predecessor as king of Babylon, commissioned foundation texts on clay cylinders – such as the Cylinder of Nabonidus, also in the British Museum – that follows the same basic formula.[53]

The text of the Cylinder thus indicates a strong continuity with centuries of Babylonian tradition, as part of an established rhetoric advanced by conquerors.[53] As Kuhrt puts it:

[The Cylinder] reflects the pressure that Babylonian citizens were able to bring to bear on the new royal claimant … In this context, the reign of the defeated predecessor was automatically described as bad and against the divine will – how else could he have been defeated? By implication, of course, all his acts became, inevitably and retrospectively, tainted.[53]

The familiarity with long-established Babylonian tropes suggests that the Cylinder was authored by the Babylonian priests of Marduk, working at the behest of Cyrus.[54] It can be compared with another work of around the same time, the Verse Account of Nabonidus, in which the former Babylonian ruler is excoriated as the enemy of the priests of Marduk and Cyrus is presented as the liberator of Babylon.[55] Both works make a point of stressing Cyrus's qualifications as a king from a line of kings, in contrast to the non-royal ancestry of Nabonidus, who is described by the Cylinder as merely maţû, "insignificant".[56]

The Verse Account is so similar to the Cyrus Cylinder inscription that the two texts have been dubbed an example of "literary dependence" – not the direct dependence of one upon the other, but mutual dependence upon a common source. This is characterised by the historian Morton Smith as "the propaganda put out in Babylonia by Cyrus's agents, shortly before Cyrus's conquest, to prepare the way of their lord".[57] This viewpoint has been disputed; as Simon J. Sherwin of the University of Cambridge puts it, the Cyrus Cylinder and the Verse Account are "after the event" compositions which reuse existing Mesopotamian literary themes and do not need to be explained as the product of pre-conquest Persian propaganda.[58]

The German historian Hanspeter Schaudig has identified a line on the Cylinder ("He [i.e. Marduk] saved his city Babylon from its oppression") with a line from tablet VI of the Babylonian "Epic of Creation", Enûma Eliš, in which Marduk builds Babylon.[59] Johannes Haubold suggests that reference represents Cyrus's takeover as a moment of ultimate restoration not just of political and religious institutions, but of the cosmic order underpinning the universe.[60]

Analysis of the Cyrus Cylinder's claims

Vilification of Nabonidus

The Cyrus Cylinder's vilification of Nabonidus is consistent with other Persian propaganda regarding the deposed king's rule. In contrast to the Cylinder's depiction of Nabonidus as an illegitimate ruler who ruined his country, the reign of Nabonidus was largely peaceful, he was recognised as a legitimate king and he undertook a variety of building projects and military campaigns commensurate with his claim to be "the king of Babylon, the universe, and the four corners [of the Earth]".[61]

Nabonidus as actually seen in Babylon

The Assyriologist Paul-Alain Beaulieu has interpreted Nabonidus's exaltation of the moon god Sin as "an outright usurpation of Marduk's prerogatives by the moon god".[62] Although the Babylonian king continued to make rich offerings to Marduk, his greater devotion to Sin was unacceptable to the Babylonian priestly elite.[63] Nabonidus came from the unfashionable north of Babylonia, introduced foreign gods and went into a lengthy self-imposed exile which was said to have prevented the celebration of the vital New Year festival.[64]

Nabonidus as seen in the Harran Stela, contrasted with the Cyrus Cylinder

The Harran Stela[65] is generally acknowledged as a genuine document commissioned by Nabonidus.[66] In it, Nabonidus seeks to glorify his own accomplishments, notably his restoration of the Elhulhul Temple, which was devoted to the moon-god Sin. In this regard, the Harran Stela verifies the picture that is dwelt on in the Cyrus Cylinder, that Nabonidus had largely abandoned the homage due to Marduk, chief god of Babylon, in favor of the worship of Sin. Since his mother Addagoppe was apparently a priestess of Sin, or at least a lifelong devotee, this helps explain the unwise political decision regarding Marduk on the part of Nabonidus, a decision that Cyrus takes great advantage of in the Cyrus Cylinder. His mother was also a resident of Harran, which affords another reason why Nabonidus moved there in the third year of his reign (553 BC), at which time he “entrusted the “Camp” to his oldest (son) [Belshazzar], the first-born . . . He let (everything) go, entrusted the kingship to him.”[67]

In at least one respect, however, the Harran Stela is incongruous with the portrayal of events in the Cyrus Cylinder. In the Stela, Nabonidus lists the enemies of Babylon as “the king of Egypt, the Medes and the land of the Arabs, all the hostile kings.” The significance of this lies in the date the Stela was composed: According to Paul-Alain Beaulieu, its composition dates to the latter part of the reign of Nabonidus, probably the fourteenth or fifteenth year, i.e. 542–540 BC.[68] The problem with this is that, according to the current consensus view, based largely on the Cyrus Cylinder and later Persian documents that followed in its genre, the Persians should have been named here as a major enemy of Babylon at a time three years or less before the fall of the city to the forces under Cyrus. Nabonidus, however, names the Medes, not the Persians, as a main enemy; as king of the realm he would certainly know who his enemies were. By naming the Medes instead of the Persians, the Harran Stela is more in conformity with the narration of events in Xenophon's Cyropaedia, where Cyrus and the Persians were under the de jure suzerainty of the Medes until shortly after the fall of Babylon, at which time Cyrus, king of Persia, became king of the Medes as well.

A further discussion of the relationship of the Harran Stela (=Babylonian propaganda) to the Cyrus Cylinder (=Persian propaganda) is found on the Harran Stela page, including a discussion of why the Cyrus Cylinder and later Persian texts never name Belshazzar, despite his close association with events associated with the fall of Babylon, as related both in the Bible (Daniel, chapter 5) and in Xenophon's Cyropaedia.[69]

Conquest and local support

Cyrus's conquest of Babylonia was resisted by Nabonidus and his supporters, as the Battle of Opis demonstrated. Iranologist Pierre Briant comments that "it is doubtful that even before the fall of [Babylon] Cyrus was impatiently awaited by a population desperate for a 'liberator'."[70] However, Cyrus's takeover as king does appear to have been welcomed by some of the Babylonian population.[71] The Judaic historian Lisbeth S. Fried says that there is little evidence that the high-ranking priests of Babylonia during the Achaemenid period were Persians and characterises them as Babylonian collaborators.[72]

The text presents Cyrus as entering Babylon peacefully and being welcomed by the population as a liberator. This presents an implicit contrast with previous conquerors, notably the Assyrian rulers Tukulti-Ninurta I, who invaded and plundered Babylon in the 12th century BC, and Sennacherib, who did the same thing 150 years before Cyrus conquered the region.[13] The massacre and enslavement of conquered people was common practice and was explicitly highlighted by conquerors in victory statements. The Cyrus Cylinder presents a very different message; Johannes Haubold notes that it portrays Cyrus's takeover as a harmonious moment of convergence between Babylonian and Persian history, not a natural disaster but the salvation of Babylonia.[59]

However, the Cylinder's account of Cyrus's conquest clearly does not tell the whole story, as it suppresses any mention of the earlier conflict between the Persians and the Babylonians;[59] Max Mallowan describes it as a "skilled work of tendentious history".[64] The text omits the Battle of Opis, in which Cyrus's forces defeated and apparently massacred Nabonidus's army.[3][73][74] Nor does it explain a two-week gap reported by the Nabonidus Chronicle between the Persian entry into Babylon and the surrender of the Esagila temple. Lisbeth S. Fried suggests that there may have been a siege or stand-off between the Persians and the temple's defenders and priests, about whose fate the Cylinder and Chronicle makes no mention. She speculates that they were killed or expelled by the Persians and replaced by more pro-Persian members of the Babylonian priestly elite.[75] As Walton and Hill put it, the claim of a wholly peaceful takeover acclaimed by the people is "standard conqueror's rhetoric and may obscure other facts".[76] Describing the claim of one's own armies being welcomed as liberators as "one of the great imperial fantasies", Bruce Lincoln, Professor of Divinity at the University of Chicago, notes that the Babylonian population repeatedly revolted against Persian rule in 522 BC, 521 BC, 484 BC and 482 BC (though not against Cyrus or his son Cambeses). The rebels sought to restore national independence and the line of native Babylonian kings – perhaps an indication that they were not as favourably disposed towards the Persians as the Cylinder suggests.[77]

Restoration of temples

The inscription goes on to describe Cyrus returning to their original sanctuaries the statues of the gods that Nabonidus had brought to the city before the Persian invasion. This restored the normal cultic order to the satisfaction of the priesthood. It alludes to temples being restored and deported groups being returned to their homelands but does not imply an empire-wide programme of restoration. Instead, it refers to specific areas in the border region between Babylonia and Persia, including sites that had been devastated by earlier Babylonian military campaigns. The Cylinder indicates that Cyrus sought to acquire the loyalty of the ravaged regions by funding reconstruction, the return of temple properties and the repatriation of the displaced populations. However, it is unclear how much actually changed on the ground; there is no archaeological evidence for any rebuilding or repairing of Mesopotamian temples during Cyrus's reign.[47]

Internal policy

The Persians' policy towards their subject people, as described by the Cylinder, was traditionally viewed as an expression of tolerance, moderation and generosity "on a scale previously unknown".[78] The policies of Cyrus toward subjugated nations have been contrasted to those of the Assyrians and Babylonians, who had treated subject peoples harshly; he permitted the resettling of those who had been previously deported and sponsored the reconstruction of religious buildings.[79] Cyrus was often depicted positively in Western tradition by sources such as the Old Testament of the Bible and the Greek writers Herodotus and Xenophon.[80][81] The Cyropaedia of Xenophon was particularly influential during the Renaissance when Cyrus was romanticised as an exemplary model of a virtuous and successful ruler.[82]

Modern historians argue that while Cyrus's behavior was indeed conciliatory, it was driven by the needs of the Persian Empire, and was not an expression of personal tolerance per se.[83] The empire was too large to be centrally directed; Cyrus followed a policy of using existing territorial units to implement a decentralized system of government. The magnanimity shown by Cyrus won him praise and gratitude from those he spared.[84] The policy of toleration described by the Cylinder was thus, as biblical historian Rainer Albertz puts it, "an expression of conservative support for local regions to serve the political interests of the whole [empire]".[85] Another biblical historian, Alberto Soggin, comments that it was more "a matter of practicality and economy … [as] it was simpler, and indeed cost less, to obtain the spontaneous collaboration of their subjects at a local level than to have to impose their sovereignty by force".[86]

Differences between the Cyrus Cylinder and previous Babylonian and Assyrian cylinders

There are scholars who agree that the Cyrus Cylinder demonstrates a break from past traditions, and the ushering in of a new era.[87] A comparison of the Cyrus Cylinder with the inscriptions of previous conquerors of Babylon highlights this sharply. For instance, when Sennacherib, king of Assyria(705-681 BC) captured the city in 690 BC after a 15-month siege, Babylon endured a dreadful destruction and massacre.[88] Sennacharib describes how, having captured the King of Babylon, he had him tied up in the middle of the city like a pig. Then he describes how he destroyed Babylon, and filled the city with corpses, looted its wealth, broke its gods, burned and destroyed its houses down to foundations, demolished its walls and temples and dumped them in the canals. This is in stark contrast to Cyrus the Great and the Cyrus Cylinder. The past Assyrian, and Babylonian tradition of victor's justice was a common treatment for a defeated people at this time. Sennacherib's tone for instance, reflected his relish of and pride in massacre and destruction, which is totally at odds with the message of the Cyrus Cylinder.[88][89]

Another difference between the previously mentioned texts and the Cyrus Cylinder is that no other king ever returned captives to their homes as Cyrus did.[90] The Assyrians sometimes gave limited religious freedom to local cults and the people they conquered, but after a military conquest, the conquered people usually had to submit to the 'exalted might' of the Assyrian god Ashur; their own shrines and gods were demolished and people put under 'the yoke of Ashur.' Even Babylon itself did not show tolerance towards other beliefs and cults, for it had destroyed the temple of Jerusalem as well as the temple in Harran; furthermore, Nabonidus took other gods from their sacred shrines, and carried them to Babylon. This clearly shows that the Cyrus Cylinder was not a typical declaration that was keeping with the old traditions of the past.[90]

However, Sennacherib's destruction of Babylon can not be taken as the norm, and solely judging from Sennacherib’s own inscriptions, the destruction was already bad by Neo-Assyrian standards.[91] The destruction of cult statues has precedence in the Ancient Near East, such as Lugalzagesi claiming to have plundered the shrines and destroyed the cult statues of his enemy state Lagash,[92] but the destruction of cult statues was the more severe and extreme treatment.[93] Nabonidus likely gathered cult statues to Babylon to prepare for an incoming Persian attack, and this tradition has precedence with Merodach-Baladan who also brought the statues to Dur-Yakin to keep them from the Assyrians, and some Babylonian cities also sent their statues to Babylon in 626 BCE in light of Sin-shar-ishkun's advance.[94]

Other scholars disagree with the view that Cyrus had a policy of religious tolerance, which stood in contrast to the Assyrians and Babylonians. This assumes a religious discourse that compelled the ancients to suppress the worship of other gods, but no such discourse existed.[95] Reverence for the gods of Assyria did not prevent the existence of local cults, for example Sargon after his conquest of the Harhar region reconstructed the local temples and returned the statues of the gods.[96] In treaties conducted with vassals, local gods were invoked alongside Assyrian gods in the oath treaties in the curse sections,[97] indicating that the presence of the gods of both parties were required for the oath[98] and the oath treaties never carried a stipulation on the worship of Assyrian gods or the hindrance of worship on local gods.[99] Similar to Achaemenid ideology, the acceptance of the power of the Assyrian king was synonymous to the acceptance of the power of their god, particularly Assur, but worship of the Assyrian gods were not forcibly imposed and recognition of Assyrian power entails the recognition of the superior strength of their gods.[100]

The return of divine statues and people, commonly seen as a special Achaemenid policy, was also attested in Assyrian sources. Esarhaddon, after repairing the statues of the Arabian gods and engraving an inscription to serve as remembrance of Assyria's power, returned the statues on Hazail's request.[101] accounts on returning statues are also found in the epithets of Esarhaddon.[102] Adad-nirari III claims to have brought back abducted people, and Esarhaddon brought back Babylonians who had been displaced following Sennacherib’s destruction of the city to the reconstructed Babylon.[103] Briant summarizes that this view that Cyrus was exceptional only arises if one only takes into account Jewish sources, and the idea disappears if placed in the context of the Ancient Near East. [104]

Biblical interpretations

The Bible records that some Jews (who were exiled by the Babylonians), returned to their homeland from Babylon, where they had been settled by Nebuchadnezzar, to rebuild the temple following an edict from Cyrus. The Book of Ezra (1–4:5) provides a narrative account of the rebuilding project.[105] Scholars have linked one particular passage from the Cylinder to the Old Testament account:[46]

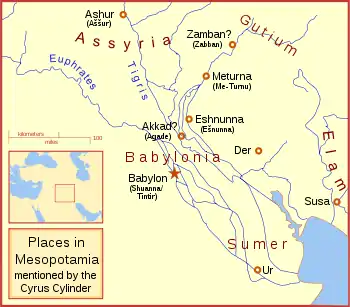

From [?][106] to Aššur and [from] Susa, Agade, Ešnunna, Zabban, Me-Turnu, Der, as far as the region of Gutium, the sacred centers on the other side of the Tigris, whose sanctuaries had been abandoned for a long time, I returned the images of the gods, who had resided there [i.e., in Babylon], to their places and I let them dwell in eternal abodes. I gathered all their inhabitants and returned to them their dwellings.[107]

This passage has often been interpreted as a reference to the benign policy instituted by Cyrus of allowing exiled peoples, such as the Jews, to return to their original homelands.[6] The Cylinder's inscription has been linked with the reproduction in the Book of Ezra of two texts that are claimed to be edicts issued by Cyrus concerning the repatriation of the Jews and the reconstruction of the Temple in Jerusalem.[108] The two edicts (one in Hebrew and one in Aramaic) are substantially different in content and tone, leading some historians to argue that one or both may be a post hoc fabrication.[109] The question of their authenticity remains unresolved, though it is widely believed that they do reflect some sort of Persian royal policy, albeit perhaps not one that was couched in the terms given in the text of the biblical edicts.

The dispute over the authenticity of the biblical edicts has prompted interest in this passage from the Cyrus Cylinder, specifically concerning the question of whether it indicates that Cyrus had a general policy of repatriating subject peoples and restoring their sanctuaries.[110] The text of the Cylinder is very specific, listing places in Mesopotamia and the neighboring regions. It does not describe any general release or return of exiled communities but focuses on the return of Babylonian deities to their own home cities. It emphasises the re-establishment of local religious norms, reversing the alleged neglect of Nabonidus – a theme that Amélie Kuhrt describes as "a literary device used to underline the piety of Cyrus as opposed to the blasphemy of Nabonidus". She suggests that Cyrus had simply adopted a policy used by earlier Assyrian rulers of giving privileges to cities in key strategic or politically sensitive regions and that there was no general policy as such.[111] Lester L. Grabbe, a historian of early Judaism, has written that "the religious policy of the Persians was not that different from the basic practice of the Assyrians and Babylonians before them" in tolerating – but not promoting – local cults, other than their own gods.[112]

Cyrus may have seen Jerusalem, situated in a strategic location between Mesopotamia and Egypt, as worth patronising for political reasons. His Achaemenid successors generally supported indigenous cults in subject territories and thereby curried favour with the cults' devotees.[113] Conversely, Persian kings might destroy the shrines of peoples who had rebelled against them, as happened at Miletos in 494 BC following the Ionian Revolt.[114] The Cylinder's text does not describe any general policy of a return of exiles or mention any sanctuary outside Babylonia[7] therein supporting Peter Ross Bedford's argument that the Cylinder is "not a manifesto for a general policy regarding indigenous cults and their worshippers throughout the empire".[115] Amélie Kuhrt notes that "the purely Babylonian context of the Cylinder provides no proof" that Cyrus gave attention to the Jewish exiles or the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem[46] and biblical historian Bob Becking concludes that "it has nothing to do with Judeans, Jews or Jerusalem". Becking also points to the lack of reference to the Jews in surviving Achaemenid texts as an indication that they were not considered of any particular importance.[6]

The German scholar Josef Wiesehöfer summarizes the widely held traditional view by noting that "Many scholars have read into [... the text of Cylinder] a confirmation of the Old Testament passages about the steps taken by Cyrus towards the erection of the Jerusalem temple and the repatriation of the Judaeans" and that this interpretation undergirded a belief "that the instructions to this effect were actually provided in these very formulations of the Cyrus Cylinder".[29]

Human rights

The Cylinder gained new prominence in the late 1960s when the last Shah of Iran called it "the world's first charter of human rights".[116] The cylinder was a key symbol of the Shah's political ideology and is still regarded by some commentators as a charter of human rights, despite the disagreement of some historians and scholars.[9]

Pahlavi Iranian government's view

The Cyrus Cylinder was dubbed the "first declaration of human rights" by the pre-Revolution Iranian government,[117] a reading prominently advanced by Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, in a 1967 book, The White Revolution of Iran. The Shah identified Cyrus as a key figure in government ideology and associated his government with the Achaemenids.[118] He wrote that "the history of our empire began with the famous declaration of Cyrus, which, for its advocacy of humane principles, justice and liberty, must be considered one of the most remarkable documents in the history of mankind."[119] The Shah described Cyrus as the first ruler in history to give his subjects "freedom of opinion and other basic rights".[119] In 1968, the Shah opened the first United Nations Conference on Human Rights in Tehran by saying that the Cyrus Cylinder was the precursor to the modern Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[120]

In his 1971 Nowruz (New Year) speech, the Shah declared that 1350 AP (1971–1972) would be Cyrus the Great Year, during which a grand commemoration would be held to celebrate 2,500 years of Persian monarchy. It would serve as a showcase for a modern Iran in which the contributions that Iran had made to world civilization would be recognized. The main theme of the commemoration was the centrality of the monarchy within Iran's political system, associating the Shah of Iran with the famous monarchs of Persia's past, and with Cyrus in particular.[9] The Shah looked to the Achaemenid period as "a moment from the national past that could best serve as a model and a slogan for the imperial society he hoped to create".[121]

The Cyrus Cylinder was adopted as the symbol for the commemoration, and Iranian magazines and journals published numerous articles about ancient Persian history.[9] The British Museum loaned the original Cylinder to the Iranian government for the duration of the festivities; it was put on display at the Shahyad Monument (now the Azadi Tower) in Tehran.[122] The 2,500 year celebrations commenced on October 12, 1971, and culminated a week later with a spectacular parade at the tomb of Cyrus in Pasargadae. On October 14, the shah's sister, Princess Ashraf Pahlavi, presented the United Nations Secretary General U Thant with a replica of the Cylinder. The princess asserted that "the heritage of Cyrus was the heritage of human understanding, tolerance, courage, compassion and, above all, human liberty".[10] The Secretary General accepted the gift, linking the Cylinder with the efforts of the United Nations General Assembly to address "the question of Respect for Human Rights in Armed Conflict".[10] Since then the replica Cylinder has been kept at the United Nations Headquarters in New York City on the second floor hallway.[10] The United Nations continues to promote the cylinder as "an ancient declaration of human rights".[36]

Reception in the Islamic Republic

In September 2010, former Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad officially opened the Cyrus Cylinder exhibition at the National Museum of Iran. After the Pahlavi era, it was the second time the cylinder was brought to Iran. It was also its longest-running exhibition inside the country. Ahmadinejad considers the Cyrus Cylinder as the incarnation of human values and a cultural heritage for all humanity, and called it the "First Charter of Human Rights". The British Museum had loaned the Cyrus Cylinder to the National Museum of Iran for four months.

The Cylinder reads that everyone is entitled to freedom of thought and choice and all individuals should pay respect to one another. The historical charter also underscores the necessity of fighting oppression, defending the oppressed, respecting human dignity, and recognizing human rights. The Cyrus Cylinder bears testimony to the fact that the Iranian nation has always been the flag-bearer of justice, devotion and human values throughout history.

Some Iranian politicians such as MP Ali Motahari criticized Ahmadinejad for bringing the Cyrus Cylinder to Iran, although Tehran daily Kayhan, viewed as an ultra-conservative newspaper, had opined that the Islamic Republic should never have returned the Cyrus Cylinder to Britain (note that the cylinder was not discovered in Iran, but in present-day Iraq):

There is an important question: Doesn't the cylinder belong to Iran? And hasn't the British government stolen ancient artifacts from our country? If the answers to these questions are positive, then why should we return this stolen historical and valuable work to the thieves?

— Kayhan newspaper during Cyrus Cylinder exhibition in Iran

At the time, the Curator of the National Museum of Iran, Azadeh Ardakani, reported approximately 48,000 visitors to the Cylinder exhibition, amongst whom over 2000 were foreigners, including foreign ambassadors.

Scholarly views

The interpretation of the Cylinder as a "charter of human rights" has been described by various historians as "rather anachronistic" and tendentious.[11][123][124][125][14] It has been dismissed as a "misunderstanding"[12] and characterized as political propaganda devised by the Pahlavi regime.[111] The German historian Josef Wiesehöfer comments that the portrayal of Cyrus as a champion of human rights is as illusory as the image of the "humane and enlightened Shah of Persia".[118] D. Fairchild Ruggles and Helaine Silverman describe the Shah's aim as being to legitimise the Iranian nation and his own regime, and to counter the growing influence of Islamic fundamentalism by creating an alternative narrative rooted in the ancient Persian past.[126]

Writing in the immediate aftermath of the Shah's anniversary commemorations, the British Museum's C.B.F. Walker comments that the "essential character of the Cyrus Cylinder [is not] a general declaration of human rights or religious toleration but simply a building inscription, in the Babylonian and Assyrian tradition, commemorating Cyrus's restoration of the city of Babylon and the worship of Marduk previously neglected by Nabonidus".[22] Two professors specialising in the history of the ancient Near East, Bill T. Arnold and Piotr Michalowski, comment: "Generically, it belongs with other foundation deposit inscriptions; it is not an edict of any kind, nor does it provide any unusual human rights declaration as is sometimes claimed."[13] Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones of the University of Edinburgh notes that "there is nothing in the text" that suggests the concept of human rights.[124] Neil MacGregor comments:

Comparison by scholars in the British Museum with other similar texts, however, showed that rulers in ancient Iraq had been making comparable declarations upon succeeding to the [Babylonian] throne for two millennia before Cyrus […] it is one of the museum's tasks to resist the narrowing of the object's meaning and its appropriation to one political agenda.[116]

He cautions that while the Cylinder is "clearly linked with the history of Iran," it is "in no real sense an Iranian document: it is part of a much larger history of the ancient Near East, of Mesopotamian kingship, and of the Jewish diaspora".[116] In a similar vein, Qamar Adamjee of the Asian Art Museum describes it as a "very traditional kingship document" and cautions that "it's anachronistic to use 20th century terms to describe events that happened two thousand five hundred years ago."[14]

Non-specialist writers on human rights have supported the interpretation of the Cyrus Cylinder as a human rights charter.[127][128] W.J. Talbott, an American philosopher, believes the concept of human rights is a 20th-century concept but describes Cyrus as "perhaps the earliest known advocate of religious tolerance" and suggests that "ideas that led to the development of human rights are not limited to one cultural tradition."[129] The Iranian lawyer Hirad Abtahi argues that viewing the Cylinder as merely "an instrument of legitimizing royal rule" is unjustified, as Cyrus issued the document and granted those rights when he was at the height of his power, with neither popular opposition nor visible external threat to force his hand.[130]

Exhibition history

The Cyrus Cylinder has been displayed in the British Museum since its formal acquisition in 1880.[1] It has been loaned four times – twice to Iran, between 7–22 October 1971 in conjunction with the 2,500 year celebration of the Persian Empire and again from September–December 2010, once to Spain from March–June 2006,[1] and once to the United States in a traveling exhibition from March–October 2013. Many replicas have been made. Some were distributed by the Shah following the 1971 commemorations, while the British Museum and National Museum of Iran have sold them commercially.[1]

The British Museum's ownership of the Cyrus Cylinder has been the cause of some controversy in Iran, although the artifact was obtained legally and was not excavated on Iranian soil but on former Ottoman territory (modern Iraq). When it was loaned in 1971, the Iranian press campaigned for its transfer to Iranian ownership. The Cylinder was brought back to London without difficulty, but the British Museum's Board of Trustees subsequently decided that it would be "undesirable to make a further loan of the Cylinder to Iran."[1]

In 2005–2006 the British Museum mounted a major exhibition on the Persian Empire, Forgotten Empire: the World of Ancient Persia. It was held in collaboration with the Iranian government, which loaned the British Museum a number of iconic artefacts in exchange for an undertaking that the Cyrus Cylinder would be loaned to the National Museum of Iran in return.[131]

The planned loan of the Cylinder was postponed in October 2009 following the June 2009 Iranian presidential election so that the British Museum could be "assured that the situation in the country was suitable".[132] In response, the Iranian government threatened to end cooperation with the British Museum if the Cylinder was not loaned within the following two months.[132][133] This deadline was postponed despite appeals by the Iranian government[132][134] but the Cylinder did eventually go on display in Tehran in September 2010 for a four-month period.[135] The exhibition was very popular, attracting 48,000 people within the first ten days and about 500,000 people by the time it closed in January 2011.[136][137] However, at its opening, Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad mingled Islamic Republican and ancient Persian symbology, which commentators inside and outside Iran criticised as an overt appeal to religious nationalism.[138]

On November 28, 2012, the BBC announced the first United States tour of the Cylinder. Under the headline "British Museum lends ancient 'bill of rights' cylinder to US", Museum director Neil MacGregor declared that "The cylinder, often referred to as the first bill of human rights, 'must be shared as widely as possible'".[139] The British Museum itself announced the news in its press release, saying "'First declaration of human rights' to tour five cities in the United States".[140] According to the British Museum's website for the Cylinder's US exhibition "CyrusCylinder2013.com", the tour started in March 2013 and included Washington D.C.'s Smithsonian's Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco and culminated at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, in October 2013.[141]

The cylinder, along with thirty two other associated objects from the British Museum collection, including a pair of gold armlets from the Oxus Treasure and the Darius Seal, were part of an exhibition titled 'The Cyrus Cylinder and Ancient Persia – A New Beginning' at the Prince of Wales Museum in Mumbai, India, from December 21, 2013, to February 25, 2014. It was organised by the British Museum and the Prince of Wales Museum in partnership with Sir Dorabji Tata Trust, Sir Ratan Tata Trust and Navajbai Ratan Tata Trust, all set up by luminaries from the Parsi community, who are descendants of Persian Zoroastrians, who hold Cyrus in great regard, as many scholars consider him as a follower of Zoroastrianism.[142]

The Freedom Sculpture

The Freedom Sculpture or Freedom: A Shared Dream (Persian: تندیس آزادی) is a 2017 stainless steel public art sculpture by artist and architect Cecil Balmond, located in Century City, California, and modeled on the Cyrus Cylinder.[143][144][145]

Notes and references

- "The Cyrus Cylinder (British Museum database)". Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- Dandamayev, (2010-01-26)

- Kuhrt (2007), p. 70, 72

- British Museum: The Cyrus Cylinder

- Free & Vos (1992), p. 204

- Becking, p. 8

- Janzen, p. 157

- Barbara Slavin (6 March 2013). "Cyrus Cylinder a Reminder of Persian Legacy of Tolerance". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- Ansari, pp. 218–19.

- United Nations Press Release 14 October 1971(SG/SM/1553/HQ263 Archived 2017-08-07 at the Wayback Machine)

- Daniel, p. 39

- Mitchell, p. 83

- Arnold, pp. 426–30

- "Oldest Known Charter of Human Rights Comes to San Francisco". 13 August 2013. Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- Finkel (2009), p. 172

- Vos (1995), p. 267

- Hilprecht (1903), pp. 204–05

- Rassam (1897), p. 223

- Koldewey, p. vi

- Rassam, p. 267

- Hilprecht (1903), p. 264

- Walker, pp. 158–59

- The Times (18 November 1879)

- The Oriental Journal (January 1880)

- Rawlinson (1880), pp. 70–97

- Curtis, Tallis & André-Salvini, p. 59

- Nies & Keiser (1920)

- Berger, pp. 155–59

- Wiesehöfer (2001), pp. 44–45.

- Translation of the text on the Cyrus Cylinder Archived 2017-04-06 at the Wayback Machine. Finkel, Irving.

- Pritchard

- Kutsko, p. 123

- Weissbach, p. 2

- Schaudig, pp. 550–56

- Hallo, p. 315

- Schulz (2008-07-15)

- compare "Cyrus Cylinder". Archived from the original on 2013-06-15. Retrieved 2013-04-12. with the British Museum translation at Archived 2015-10-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Foucart (2007-08-19)

- "Shirin Ebadi's 2003 Nobel Peace Prize lecture". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- British Museum. "Irving Finkel". Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- Cyrus Cylinder (press release) Archived 2011-09-22 at the Wayback Machine. British Museum, 20 January 2010

- Yang, Zhi (1987). "Brief Note on the Bone Cuneiform Inscriptions". Journal of Ancient Civilizations. 2: 30–33.

- Finkel, Irving, ed. (2013). The Cyrus Cylinder: The King of Persia's Proclamation from Ancient Babylon. I.B.Tauris. pp. 28–34. ISBN 978-1780760636.

- Wu, Yuhong (1986). "A Horse-Bone Inscription copied from the Cyrus Cylinder (Line 18-21) in the Palace Museum in Beijing". Journal of Ancient Civilizations. 1: 15–20.

- Inscription in the British Museum, Room 55

- Kuhrt (1982), p. 124

- Winn Leith, p. 285

- Fowler & Hekster, p. 33

- British Museum: The Cyrus Cylinder; Kuhrt (1983), pp. 83–97; Dandamaev, pp. 52–53; Beaulieu, p. 243; van der Spek, pp. 273–85; Wiesehöfer (2001), p. 82; Briant, p. 43

- Haubold, p. 52 fn. 24

- British Museum e-mail (2010-01-11)

- British Museum statement (2010-01-20)

- Kuhrt (2007), pp. 174–75.

- Dyck, pp. 91–94.

- Grabbe (2004), p. 267

- Dick, p. 10

- Smith, p. 78

- Sherwin, p. 122.

- Haubold, p. 51

- Haubold, p. 52

- Bidmead, p. 137

- Bidmead, p. 134

- Bidmead, p. 135

- Mallowan, pp. 409–11

- For the text, see J. B. Pritchard, ed., Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (3rd ed.; Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1969), 562a–563b.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (1989). The Reign of Nabonidus, King of Babylon 556–539 B.C. (PDF). New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 17. ISBN 0300043147.

- Pritchard, ed., Ancient Near Eastern Texts, 313b. This cuneiform text is called the “Verse Account of Nabonidus.”

- Beaulieu, Reign of Nabonidus, 32.

- Cyropaedia 4.6.3; 5.2.27; 5.4.12, 24, 26, 33; 7.5.29. The Cyropaedia refers to Belshazzar as “this young fellow who has just come to the throne.” His death is described as occurring on the night the city was captured, which was also the time of a festival (7.5.25), in agreement with the narration of these events in the book of Daniel (5:1, 30).

- Briant, p. 43

- Buchanan, pp. 12–13

- Fried, p. 30

- Oppenheim, A. Leo, in Pritchard, James B. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. Princeton University Press, 1950

- Briant, p. 41

- Fried, p. 29

- Walton & Hill, p. 172

- Lincoln, p. 40

- Masroori, pp. 13–15

- Dandamaev, pp. 52–53

- Brown, pp. 7–8

- Arberry, p. 8

- Stillman, p. 225

- Min, p. 94

- Evans, pp. 12–13

- Albertz, pp. 115–16

- Soggin, p. 295

- Razmjou, pp. 104–125.

- Razmjou, p. 122.

- John Curtis, The Cyrus Cylinder and Ancient Persia, A New Beginning For the Middle East, pp. 31–41 ISBN 978-0714111872

- Razmjou, p. 123.

- Nielsen 2018, p. 95.

- Schaudig 2012, p. 128.

- Zaia 2015, p. 37-39.

- Beaulieu 1986, p. 223.

- van der Spek 2014, p. 235.

- Cogan 1974, p. 55.

- Cogan 1974, p. 47-49.

- Zaia 2015, p. 27.

- Cogan 1993, p. 409.

- Kuhrt 2008, p. 124.

- Cogan 1974, p. 36.

- Zaia 2015, p. 36-37.

- van der Spek 2014, p. 258.

- Briant, p. 48

- Hurowitz, pp. 581–91

- Some translations give "Nineveh." The relevant passage is fragmentary, but Finkel has recently concluded that it is impossible to interpret it as "Nineveh". (I. Finkel, "No Nineveh in the Cyrus Cylinder", in NABU 1997/23)

- Lendering, Jona (5 February 2010). "Cyrus Cylinder (2)". Livius.org. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2007. Text adapted from Schaudig (2001). English translation adapted from Cogan's translation in Hallo & Younger (2003).

- Dandamaev (2010-01-26)

- Bedford, p. 113

- Bedford, p. 134

- Kuhrt (1983), pp. 83–97

- Grabbe (2006), p. 542

- Bedford, pp. 138–39

- Greaves, Alan M. Miletos: A History, p. 84. Routledge, 2002. ISBN 978-0415238465

- Bedford, p. 137

- MacGregor

- "United Nations Note to Correspondents no. 3699, 13 October 1971" (PDF).

- Wiesehöfer (1999), pp. 55–68

- Pahlavi, p. 9

- Robertson, p. 7

- Lincoln, p. 32.

- Housego (1971-10-15)

- Briant, p. 47

- Llewellyn-Jones, p. 104

- Curtis, Tallis & Andre-Salvini, p. 59

- Silverman, Helaine; Ruggles, D. Fairchild (2008). Cultural Heritage and Human Rights. Springer. p. 11. ISBN 978-0387765792.

- Damien Kingsbury, Human Rights in Asia: A Reassessment of the Asian Values Debate (Macmillan, 2008) p. 21; Sabine C. Carey, The Politics of Human Rights: The Quest for Dignity (2010) p. 19; Paul Gordon Lauren, The Evolution of International Human Rights (2003) p. 11; Willem Adriaan Veenhoven, Case Studies on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms: A World Survey: Volume 1 (1975) p. 244

- Decolonisation, Globalisation: Language-in-Education Policy and Practice, Peter W. Martin, p. 99

- Talbott, W.J. Which Rights Should be Universal?, p. 40. Oxford University Press US, 2005. ISBN 978-0195173475

- Abtahi, pp. 1–38.

- Jeffries (2005-10-22)

- Sheikholeslami (2009-10-12)

- Wilson (2010-01-24)

- "Iran severs cultural ties with British Museum over Persian treasure (2010-02-07)"

- "Cyrus Cylinder, world's oldest human rights charter, returns to Iran on loan," The Guardian (2010-09-10)

- "Cyrus Cylinder warmly welcomed at home Archived 2011-06-14 at the Wayback Machine". Tehran Times, September 26, 2010

- "Diplomatic whirl". The Economist. 2013-03-23. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2019-07-30.

- Esfandiari, Golnaz. Historic Cyrus Cylinder Called 'A Stranger In Its Own Home' Archived 2010-09-18 at the Wayback Machine. "Persian Letters", Radio Free Europe. September 14, 2010

- "Babylonian artefact to tour US". 2012-11-28. Retrieved 2019-07-30.

- "The Cyrus Cylinder travels to the US". British Museum (Press release). Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 2019-07-30.

- "Tour Venues and Dates". Cyrus Cylinder US Tour 2013. 2013-02-28. Retrieved 2019-07-30.

- "'The Cyrus Cylinder and Ancient Persia - A New Beginning', an exhibition in partnership with three Tata trusts - Tata Sons - Tata group". Archived from the original on 2015-05-13. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- Anderton, Frances (4 July 2017). "Cecil Balmond Designs 'Freedom Sculpture' for Los Angeles". KCRW. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- "Century City Freedom Sculpture unveiled on Santa Monica Boulevard median". 2017-07-05.

- "'Los Angeles embodies diversity.' the city's new sculpture celebrating freedom is unveiled". Los Angeles Times. 5 July 2017.

Further reading

Books and journals

- Abtahi, Hirad (2006). Abtahi, Hirad; Boas, Gideon (eds.). The Dynamics of International Criminal Justice: Essays in Honour of Sir Richard May. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-9004145870.

- Albertz, Rainer (2003). Israel in Exile: The History and Literature of the Sixth Century B.C.E. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1589830554.

- Ansari, Ali (2007). Modern Iran: The Pahlavis and After. Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-1405840842.

- Arberry, A.J. (1953). The Legacy of Persia. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821905-7. OCLC 1283292.

- Arnold, Bill T.; Michalowski, Piotr (2006). "Achaemenid Period Historical Texts Concerning Mesopotamia". In Chavelas, Mark W. (ed.). The Ancient Near East: Historical Sources in Translation. London: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0631235811.

- Bedford, Peter Ross (2000). Temple Restoration in Early Achaemenid Judah. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004115095.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (1986). The Reign of Nabonidus, King of Babylon (556-539 B.C.). Yale University.

- Beaulieu, P.-A. (Oct 1993). "An Episode in the Fall of Babylon to the Persians". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 52 (4): 241–61. doi:10.1086/373633. S2CID 162399298.

- Becking, Bob (2006). ""We All Returned as One!": Critical Notes on the Myth of the Mass Return". In Lipschitz, Oded; Oeming, Manfred (eds.). Judah and the Judeans in the Persian period. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1575061047.

- Berger, P.-R. (1970). "Das Neujahrsfest nach den Königsinschriften des ausgehenden babylonischen Reiches". In Finet, A. (ed.). Actes de la XVIIe Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale. Publications du Comité belge de recherches historiques, épigraphiques et archéologiques en Mésopotamie, nr. 1 (in German). Ham-sur-Heure: Comité belge de recherches en Mésopotamie.

- Bidmead, Julye (2004). The Akitu Festival: Religious Continuity And Royal Legitimation In Mesopotamia. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press LLC. ISBN 978-1593331580.

- Briant, Pierre (2006). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbraun. ISBN 978-1575061207.

- Brown, Dale (1996). Persians: Masters of Empire. Alexandra, VA: Time-Life Books. ISBN 978-0809491049.

- Buchanan, G. (1964). "The Foundation and Extension of the Persian Empire". In Bury, J.B.; Cook, S.A.; Adcock, F.E. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: IV. The Persian Empire and the West. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 57550495.

- Cogan, Mordechai (1974). Imperialism and religion : Assyria, Judah, and Israel in the eighth and seventh centuries B.C.E. [Missoula, Mont.] : Society of Biblical Literature : distributed by Scholars Press. ISBN 978-0-88414-041-2.

- Cogan, Mordechai (1993). "Judah under Assyrian Hegemony: A Reexamination of Imperialism and Religion". Journal of Biblical Literature. 112 (3): 403–414. doi:10.2307/3267741. ISSN 0021-9231.

- Curtis, John; Tallis, Nigel; André-Salvini, Béatrice (2005). Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520247314.

- Dandamaev, M.A. (1989). A political history of the Achaemenid Empire. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004091726.

- Daniel, Elton L. (2000). The History of Iran. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313307317.

- Dick, Michael B. (2004). "The "History of David's Rise to Power" and the Neo-Babylonian Succession Apologies". In Batto, Bernard Frank; Roberts, Kathryn L.; McBee Roberts, Jimmy Jack (eds.). David and Zion: Biblical Studies in Honor of J.J.M. Roberts. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1575060927.

- Dyck, Jonathan E. (1998). The Theocratic Ideology of the Chronicler. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004111462.

- Evans, Malcolm (1997). Religious Liberty and International Law in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521550215.

- Finkel, I.L.; Seymour, M.J. (2009). Babylon. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195385403.

- Fowler, Richard; Hekster, Olivier (2005). Imaginary kings: royal images in the ancient Near East, Greece and Rome. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3515087650.

- Free, Joseph P.; Vos, Howard Frederic (1992). Vos, Howard Frederic (ed.). Archaeology and Bible history. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. ISBN 978-0310479611.

- Fried, Lisbeth S. (2004). The priest and the great king: temple-palace relations in the Persian Empire. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1575060903.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2004). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period: Yehud, the Persian Province of Judah. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0567089984.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2006). "The "Persian Documents" in the Book of Ezra: Are They Authentic?". In Lipschitz, Oded; Oeming, Manfred (eds.). Judah and the Judeans in the Persian period. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1575061047.

- Hallo, William (2002). Hallo, William; Younger, K. Lawson (eds.). The Context of Scripture: Monumental inscriptions from the biblical world. Vol. 2. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004106192.

- Haubold, Johannes (2007). "Xerxes' Homer". In Bridges, Emma; Hall, Edith; Rhodes, P.J. (eds.). Cultural Responses to the Persian Wars: Antiquity to the Third Millennium. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199279678.

- Hilprecht, Hermann Volrath (1903). Explorations in Bible lands during the 19th century. Philadelphia: A.J. Molman and Company.

- Hurowitz, Victor Avigdor (Jan–Apr 2003). "Restoring the Temple: Why and when?". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 93 (3/4).

- Janzen, David (2002). Witch-hunts, purity and social boundaries: the expulsion of the foreign women in Ezra 9–10. London: Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 978-1841272924.

- Koldewey, Robert; Griffith Johns, Agnes Sophia (1914). The excavations at Babylon. London: MacMillan & co.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (1982). "Babylonia from Cyrus to Xerxes". In Boardman, John (ed.). The Cambridge Ancient History: Vol IV – Persia, Greece and the Western Mediterranean. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521228046.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (1983). "The Cyrus Cylinder and Achaemenid imperial policy". Journal for the Study of the Old Testament. 25. ISSN 1476-6728.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (2007). The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources of the Achaemenid Period. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415436281.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (2007). "Cyrus the Great of Persia: Images and Realities". In Heinz, Marlies; Feldman, Marian H. (eds.). Representations of Political Power: Case Histories from Times of Change and Dissolving Order in the Ancient Near East. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1575061351.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (27 August 2008). "The Problem of Achaemenid 'Religious Policy'" (PDF). Die Welt der Götterbilder (in German). De Gruyter: 117–144. doi:10.1515/9783110204155.1.117/html.

- Kutsko, John F. (2000). Between Heaven and Earth: Divine Presence and Absence in the Book of Ezekiel. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1575060415.

- Lincoln, Bruce (1992). Discourse and the Construction of Society: Comparative Studies of Myth, Ritual, and Classification. New York: Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0195079098.

- Lincoln, Bruce (2007). Religion, empire and torture: the case of Achaemenian Persia, with a postscript on Abu Ghraib. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226481968.

- Llewellyn-Jones, Lloyd (2009). "The First Persian Empire 550–330 BC". In Harrison, Thomas (ed.). The Great Empires of the Ancient World. Getty Publications. p. 104. ISBN 978-0892369874.

- Mallowan, Max (1968). "Cyrus the Great (558–529 B.C.)". In Frye, Richard Nelson; Fisher, William Bayne (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 2, The Median and Achaemenian periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2. OCLC 40820893.

- Masroori, C. (1999). "Cyrus II and the Political Utility of Religious Toleration". In Laursen, J. C. (ed.). Religious Toleration: "The Variety of Rites" from Cyrus to Defoe. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0312222338.

- Min, Kyung-Jin (2004). The Levitical Authorship of Ezra-Nehemiah. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0567082268.

- Mitchell, T.C. (1988). Biblical Archaeology: Documents from the British Museum. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521368674.

- Nielsen, John Preben (2018). The reign of Nebuchadnezzar I in history and historical memory. New-York (N.Y.): Routledge. ISBN 978-1138120402.

- Nies, J.B.; Keiser, C.E. (1920). Babylonian Inscriptions in the Collection of J.B. Nies. Vol. II.

- Pahlavi, Mohammed Reza (1967). The White Revolution of Iran. Imperial Pahlavi Library.

- Pritchard, James Bennett, ed. (1973). The Ancient Near East, Volume I: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton: Princeton University Press. OCLC 150577756.

- Razmjou, Shahrokh (2013). "The Cyrus Cylinder: A Persian Perspective". In Finkel, Irving (ed.). The Cyrus Cylinder: The King of Persia's Proclamation from Ancient Babylon. London: published by I. B. Tauris & Co. Ltd. pp. 104–125. ISBN 978-1-78076-063-6.

- Rassam, Hormuzd (1897). Asshur and the land of Nimrod. London: Curts & Jennings.

- Rawlinson, H. C. (1880). "Notes on a newly-discovered clay Cylinder of Cyrus the Great". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 12.

- Robertson, Arthur Henry; Merrills, J. G. (1996). Human rights in the world : an introduction to the study of the international protection of human rights. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719049231.

- Schaudig, Hanspeter (2001). Die Inschriften Nabonids von Babylon und Kyros' des Grossen samt den in ihrem Umfeld entstandenen Tendenzschriften : Textausgabe und Grammatik (in German). Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. ISBN 978-3927120754.

- Schaudig, Hanspeter (2012). "Death of Statues and Rebirth of Gods". Iconoclasm and Text Destruction in the Ancient Near East and Beyond. Oriental Institute Seminars 8: 123–149.

- Shabani, Reza (2005). Iranian History at a Glance. Mahmood Farrokhpey (trans.). London: Alhoda UK. ISBN 978-9644390050.

- Sherwin, Simon J. (2007). "Old Testament monotheism and Zoroastrian influence". In Gordon, Robert P (ed.). The God of Israel: Studies of an Inimitable Deity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521873659.

- Smith, Morton (1996). Cohen, Shaye J.D. (ed.). Studies in the cult of Yahweh, Volume 1. Leiden: Brill. p. 78. ISBN 978-9004104778.

- Soggin, J. Alberto (1999). An Introduction to the History of Israel and Judah. John Bowman (trans.). London: SCM-Canterbury Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0334027881.

- Stillman, Robert E. (2008). Philip Sidney and the poetics of Renaissance cosmopolitanism. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0754663690.

- van der Spek, R.J. (1982). "Did Cyrus the Great introduce a new policy towards subdued nations? Cyrus in Assyrian perspective". Persica. 10. OCLC 499757419.

- van der Spek, R. J (1 January 2014). "Cyrus the Great, Exiles, and Foreign Gods: A Comparison of Assyrian and Persian Policies on Subject Nations". Extraction & Control- Studies in Honor of Matthew W. Stolper. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization (68): 233–264.

- Vos, Howard Frederic (1995). "Archaeology of Mesopotamia". In Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (ed.). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0802837813.

- Walker, C.B.F. (1972). "A recently identified fragment of the Cyrus Cylinder". Iran: Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies. 10 (10): 158–159. doi:10.2307/4300475. ISSN 0578-6967. JSTOR 4300475.

- Walton, John H.; Hill, Andrew E. (2004). Old Testament Today: A Journey from Original Meaning to Contemporary Significance. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. ISBN 978-0310238263.

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (1999). "Kyros, der Schah und 2500 Jahre Menschenrechte. Historische Mythenbildung zur Zeit der Pahlavi-Dynastie". In Conermann, Stephan (ed.). Mythen, Geschichte(n), Identitäten. Der Kampf um die Vergangenheit (in German). Schenefeld/Hamburg: EB-Verlag. ISBN 978-3930826520.

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (2001). Ancient Persia: From 550 BC to 650 AD. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1860646751.

- Weissbach, Franz Heinrich (1911). Die Keilinschriften der Achämeniden. Vorderasiatische Bibliotek (in German). Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs.

- Winn Leith, Mary Joan (1998). "Israel among the Nations: The Persian Period". In Coogan, Michael David (ed.). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195139372.

- Zaia, Shana (1 December 2015). "State-Sponsored Sacrilege: "Godnapping" and Omission in Neo-Assyrian Inscriptions". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History. 2 (1): 19–54. doi:10.1515/janeh-2015-0006. ISSN 2328-9562.

- Farrokh, Kaveh (2007). "Cyrus the Great and early Achaemenids". Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1846031083.

- Lauren, Paul Gordon (2003). "Philosophical Visions: Human Nature, Natural Law, and Natural Rights". The Evolution of International Human Rights: Visions Seen. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812218541.

Media articles

- "Royal Asiatic Society". The Times. 18 November 1879.

- "A Monument of Cyrus the Great". The Oriental Journal. London. January 1880.

- Housego, David (1971-10-15). "Pique and peacocks in Persepolis". The Times.

- Foucart, Stéphane (2007-08-19). "Cyrus le taiseux". Le Monde (in French). Archived from the original on 2013-01-07. Retrieved 2008-07-30.