Daju kingdom

The Daju kingdom was a medieval monarchy that existed in Darfur (Sudan) from possibly the 12th–15th century. Its name stems from the Daju people, the ruling ethnic group. The Daju were eventually ousted from power by the Tunjur and the last Daju king subsequently fled to present-day Chad. The sources for the Daju kingdom are almost entirely local traditions collected in the 19th and 20th century and mentions by medieval Arab historians.

Daju kingdom | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12th century–15th century | |||||||||||

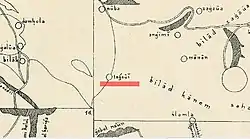

The Daju on the small map by al-Idrisi (1192 AD). North and south are swapped. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Varied per king | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Daju | ||||||||||

| Religion | Traditional African religion | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

• Established | 12th century | ||||||||||

• Last king flees to Chad | 15th century | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Sudan | ||||||||||

History

According to oral traditions, the Daju arrived in Darfur from the east or south, most likely the Shendi region in Nubia.[1] The Daju languages bear great similarity with Nobiin, matching between 10 and 25% of its vocabulary.[2] Arkell claims that Daju pottery is virtually indistinguishable from that produced in the late Meroitic kingdom.[3] Arriving in Darfur, the Daju probably supplanted the local Tora culture.[4] The Daju established their kingdom in southern Jebel Marra, from where they also exercised their influence over the adjacent regions to the south and south-east.[5] Since the 12th century they were mentioned by several contemporary Arab historians. The first is the Sicilian al-Idrisi, who wrote in 1154 that they flourished between the kingdom of Kanem and Nubia. The Daju were pagans and subject to being raided by their neighbours. He also claims that they were in fact nomads breeding camels, having only two towns; Tajuwa and Samna.[4] The latter town, he claimed, was eventually destroyed by a Nubian governor.[6] More than a century later, Ibn Sa'id writes that the Daju were now partially Islamized, while also adding that they have become vassals of Kanem.[4] Arkell postulates that Kanem not only incorporated Darfur at this time, but even stretched as far east as the Nile Valley. This large empire eventually started to collapse after the death of Dunama Dabbalemi.[7] The theory that Kanem had political dominance over Darfur is, however, contested.[8] Al-Maqrizi, who lived in the late 14th and early 15th century, repeats the information provided by Ibn Sa'id, while also adding that the Daju worked in stone and waged war against an otherwise unknown people called the Watkhu.[9]

In the 15th century the Tunjur arrived in Darfur, where they established themselves in northern Jebel Marra and ruled simultaneously with the Daju for some time.[10] They eventually seized power under unclear circumstances,[11] and the last Daju king, whose name is mostly given by the local traditions as Ahmad al-Daj,[12] fled to present-day Chad, where his successors ruled as sultans of Dar Sila.[13] The Dar Sila Daju place the migration in the early 18th century, but this would have been too late. Instead, Balfour Paul suggests the late 15th century as a more fitting date.[13]

Government

Rene Gros believes that the Daju kingdom was rather primitive in its organization, being based mainly on military dominance.[14] It was only under the Tunjur that sophisticated state organization was introduced.[15] The Daju reign is not fondly remembered in Darfur and is equated with tyranny.[1] The kings are remembered as pagans, ignorant and as raiders of the plains outside of Jebel Marra.[16] It is possible that the Daju monarchs reigned as divine kings. By drawing parallels to other divine kingships in Africa, this would mean that the king would not have shown himself in public and that he would have been ascribed to have magic abilities.[17] The title of the king was probably Bugur, a variant of the modern Daju term Buge ("sultan/chief").[18] Each king had his own palatial residence built for him.[15] After their death the Daju kings might have been buried near the Dereiba lakes, volcanic lakes at the top of Gebel Marra which served as places of pilgrimage and as oracles until the 20th century.[19]

Trading and cultural relations with Medieval Nubia

The Jewish merchant Benjamin of Tudela wrote in the 12th century that the Nubian kingdom of Alodia maintained a trading network terminating in Zwila, Libya, suggesting that the trade route went through Darfur.[20] Two Christian Nubian pottery sherds, datable to the mid-6th century-1100, were allegedly discovered in Ain Farah.[21] It has been suggested that aspects of the Medieval Nubian culture, like for example the purse as part of the royal regalia, were transmitted to the Chad basin through the Darfur area.[22]

Notes

- McGregor 2011, p. 131.

- Beswick 2004, p. 21.

- McGregor 2000, p. 50.

- McGregor 2000, p. 34.

- McGregor 2000, p. 221.

- McGregor 2000, pp. 52–53.

- Arkell 1952, pp. 264–265.

- McGregor 2000, p. 175.

- McGregor 2000, p. 36.

- McGregor 2000, pp. 221–222.

- McGregor 2000, p. 222.

- McGregor 2000, pp. 45–46.

- McGregor 2000, p. 42.

- McGregor 2000, p. 47.

- McGregor 2011, p. 132.

- McGregor 2000, p. 46.

- Arkell 1951, p. 236.

- McGregor 2000, p. 46, note 67.

- McGregor 2000, pp. 55–57.

- Zarroug 1991, pp. 87&98.

- McGregor 2011, p. 134.

- Welsby 2002, p. 87.

References

- Arkell, A. J. (1951). "History of Darfur 1200–1700 A. D." (PDF). Sudan Notes and Records. 32: 37–70, 207–238.

- Arkell, A. J. (1952). "History of Darfur 1200–1700 A. D.". Sudan Notes and Records. 33: 244–275.

- Beswick, Stephanie (2004). Sudan's Blood Memory. University of Rochester. ISBN 1580462316.

- McGregor, Andrew (2000). The Stone Monuments and Antiquities of the Jebel Marra Region, Darfur, Sudan c. 1000–1750 (PDF).

- McGregor, Andrew (2011). "Palaces in the Mountains: An Introduction to the Archaeological Heritage of the Sultanate of Darfur". Sudan&Nubia. 15: 129–141.

- Welsby, Derek (2002). The Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia. Pagans, Christians and Muslims Along the Middle Nile. British Museum. ISBN 0714119474.

- Zarroug, Mohi El-Din Abdalla (1991). The Kingdom of Alwa. University of Calgary. ISBN 0-919813-94-1.