Darkness at Noon

Darkness at Noon (German: Sonnenfinsternis) is a novel by Hungarian-born novelist Arthur Koestler, first published in 1940. His best known work, it is the tale of Rubashov, an Old Bolshevik who is arrested, imprisoned, and tried for treason against the government that he helped to create.

First US edition | |

| Author | Arthur Koestler |

|---|---|

| Original title | Sonnenfinsternis |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | German/English[nb 1] |

| Publisher | Macmillan |

Publication date | 1940 |

Published in English | 1940, 2019 |

| Pages | 254 pp (Danube edition) |

| OCLC | 21947763 |

| Preceded by | The Gladiators |

| Followed by | Arrival and Departure |

The novel is set between 1938 and 1940, after the Stalinist Great Purge and Moscow show trials. Despite being based on real events, the novel does not name either Russia or the Soviets, and tends to use generic terms to describe people and organizations: for example the Soviet government is referred to as "the Party" and Nazi Germany is referred to as "the Dictatorship". Joseph Stalin is represented by "Number One", a menacing dictator. The novel expresses the author's disillusionment with the Bolshevik ideology of the Soviet Union at the outset of World War II.

In 1998, the Modern Library ranked Darkness at Noon number eight on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century, even though Koestler wrote it in German.

Background

Koestler wrote Darkness at Noon as the second part of a trilogy: the first volume was The Gladiators (1939), first published in Hungarian. It was a novel about the subversion of the Spartacus revolt. The third novel was Arrival and Departure (1943), about a refugee during World War II. Koestler, who was by then living in London, rewrote that novel in English after the original German version had been lost.

Darkness at Noon was commenced in German while Koestler was living in Paris, and, as he describes in the first chapter of Scum of the Earth, completed in the summer of 1939, just outside the village of Belvédère in the Alpes-Maritimes where he was staying with his companion, the sculptor Daphne Hardy, who translated it into English while she was living with him. For decades the German text was thought to have been lost during the escape of Koestler and Hardy from Paris in May 1940, just before the German occupation of France. However, a copy had been sent to Swiss publisher Emil Oprecht. Rupert Hart-Davis, Koestler's editor at Jonathan Cape in London had misgivings about the English text but agreed to publish it when a request to Oprecht for his copy went unanswered.[1] At Hart-Davis' prompting, and unable to reach Koestler, Hardy changed the title from The Vicious Circle to Darkness at Noon.[1] The new title is a reference to Job 5:14: "They meet with darkness in the daytime, and grope in the noonday as in the night"— a description of the moral dilemmas faced by the book's protagonist, as well as Koestler's own escape from the Nazis.[2] In August 2015, Oprecht's copy was identified in a Zurich library by a doctoral candidate of the University of Kassel.[1][3] The original German manuscript was published as Sonnenfinsternis (Solar Eclipse) in May 2018 by Elsinor Verlag.[4] A new professional English translation based on the newfound text was published in 2019.[5]

In his introduction to the 2019 translation, Koestler biographer Michael Scammell writes that a fresh translation was desirable because Hardy's, though "serving the novel well for over seven decades", had difficulties. "She had been forced by circumstances to work in haste, with no dictionaries or other resources available for consultation, which exposed her understandable lack of familiarity with the Soviet and Nazi machinery of totalitarianism.... The text she worked on was not quite final either.... It seemed that a fresh and up-to-date translation of the novel would be helpful, preferably by a seasoned translator with the knowledge and experience to clarify the jargon of Marxism–Leninism and present it in terminology that is both accurate and makes sense to an English-speaking reader". Philip Boehm, Scammell writes, "proved the ideal choice for the job".[6][7]

In his autobiographical The Invisible Writing (1954), Koestler states that he finished Darkness at Noon in April 1940, after many troublesome months of 1939, caused mainly by financial difficulties and the later outbreak of World War II. Koestler notes:

The first obstacle was that, half-way through the book, I again ran out of money. I needed another six months to finish it, and to secure the necessary capital I had to sacrifice two months - April and May 1939 - to the writing of yet another sex book (L'Encyclopédie de la famille), the third and last. Then, after three months of quiet work in the South of France, came the next hurdle: on September 3 the War broke out, and on October 2 I was arrested by the French police.

Koestler, then, describes the unfolding of what he calls 'Kafkaesque events' in his life; spending four months in the concentration camp in the Pyrenees and being released in January 1940, only to be continuously harassed by the police. "During the next three months I finished the novel in the hours snatched between interrogations and searches of my flat, in the constant fear that I would be arrested again and the manuscript of Darkness at Noon confiscated".

After Hardy mailed her translation to London in May 1940, she fled to London. Meanwhile, Koestler joined the French Foreign Legion, deserted it in North Africa, and made his way to Portugal.[8][9][7]

Waiting in Lisbon for passage to Great Britain, Koestler heard a false report that the ship taking Hardy to England had been torpedoed and all persons lost (along with his only manuscript); he attempted suicide.[10][11] (He wrote about this incident in Scum of the Earth (1941), his memoir of that period.) Koestler finally arrived in London, and the book was published there in early 1941.

Setting

Darkness at Noon is an allegory set in the USSR (not named) during the 1938 purges as Stalin consolidated his dictatorship by eliminating potential rivals within the Communist Party: the military, and also the professionals. None of this is identified explicitly in the book. Most of the novel occurs within an unnamed prison and in the recollections of the main character, Rubashov.

Koestler drew on the experience of being imprisoned by Francisco Franco's officials during the Spanish Civil War, which he described in his memoir, Dialogue with Death. He was kept in solitary confinement and expected to be executed. He was permitted to walk in the courtyard in the company of other prisoners. Though he was not beaten, he believed that other prisoners were.

Characters

The main character is Nikolai Salmanovich Rubashov, a man in his fifties whose character is based on "a number of men who were the victims of the so-called Moscow trials", several of whom "were personally known to the author".[12] Rubashov is a stand-in for the Old Bolsheviks as a group,[13] and Koestler uses him to explore their actions at the 1938 Moscow Show Trials.[14][15]

Secondary characters include some fellow prisoners:

- No. 402 is a Czarist army officer and veteran inmate[16] with, as Rubashov would consider it, an archaic sense of personal honor.

- "Rip Van Winkle", an old revolutionary demoralised and apparently driven to madness by 20 years of solitary confinement and further imprisonment.[17]

- "Harelip", who "sends his greetings" to Rubashov, but insists on keeping his name secret.[18]

Two other secondary characters never make a direct appearance but are mentioned frequently:

- Number One, representing Joseph Stalin, dictator of the USSR. He is depicted in a widely disseminated photograph, a "well-known color print that hung over every bed or sideboard in the country and stared at people with its frozen eyes".[19]

- Old Bolsheviks. They are represented by an image in his "mind's eye, a big photograph in a wooden frame: the delegates to the first congress of the Party", in which they sat "at a long wooden table, some with their elbows propped on it, others with their hands on their knees, bearded and earnest".[20]

Rubashov has two interrogators:

- Ivanov, a comrade from the civil war and old friend.

- Gletkin, a young man characterised by starching his uniform so that it "cracks and groans" whenever he moves.[21]

Character described in flashbacks and in the third interrogation:

- Orlova, Rubashov's secretary and lover.

Plot summary

Structure

Darkness at Noon is divided into four parts: The First Hearing, The Second Hearing, The Third Hearing, and The Grammatical Fiction. In the original English translation, Koestler's word that Hardy translated as "Hearing" was "Verhör". In the 2019 translation, Boehm translated it as "Interrogation". In his introduction to that translation, Michael Scammell writes that "hearing" made the Soviet and Nazi "regimes look somewhat softer and more civilized than they really were".

The First Hearing

The line "Nobody can rule guiltlessly", by Louis Antoine de Saint-Just, appears as the epigraph. The action begins with Rubashov's arrest in the middle of the night by two men from the secret police (in the USSR, this would be the NKVD). When they came for Rubashov they woke him from a recurring dream, a replay of the first time he was arrested by the Gestapo.[22] One of the men is about Rubashov's age, the other is somewhat younger. The older man is formal and courteous, the younger is brutal.[23]

Imprisoned, Rubashov is at first relieved to be finished with the anxiety of dread during mass arrests. He is expecting to be kept in solitary confinement until he is shot.[24] He begins to communicate with No. 402, the man in the adjacent cell, by using a tap code. Unlike Rubashov, No. 402 is not an intellectual, but rather a Tsarist army officer, who hates communists. Their relationship begins on a sour note as No. 402 expresses delight at Rubashov's political misfortune; however No. 402 has non-political urges too, and when he pleads for Rubashov to give him details about the last time he slept with a woman, once Rubashov does so No. 402 warms up to him. The two grow closer over time and exchange information about the prison and its inmates.[25]

Rubashov thinks of the Old Bolsheviks, Number One, and the Marxist interpretation of history. Throughout the novel Rubashov, Ivanov, and Gletkin speculate about historical processes and how individuals and groups are affected by them. Each hopes that, no matter how vile his actions may seem to their contemporaries, history will eventually absolve them. This is the faith that makes the abuses of the regime tolerable as the men consider the suffering of a few thousand, or a few million people against the happiness of future generations. They believe that gaining the socialist utopia, which they believe is possible, will cause the imposed suffering to be forgiven.

Rubashov meditates on his life: since joining the Party as a teenager, Rubashov has officered soldiers in the field,[26] won a commendation for "fearlessness",[27] repeatedly volunteered for hazardous assignments, endured torture,[28] betrayed other communists who deviated from the Party line,[29] and proven that he is loyal to its policies and goals. Recently he has had doubts. Despite 20 years of power, in which the government caused the deliberate deaths and executions of millions, the Party does not seem to be any closer to achieving the goal of a socialist utopia. That vision seems to be receding.[30] Rubashov is in a quandary, between a lifetime of devotion to the Party on the one hand, and his conscience and the increasing evidence of his own experience on the other.

From this point, the narrative switches back and forth between his current life as a political prisoner and his past life as one of the Party elite. He recalls his first visit to Berlin about 1933, after Adolf Hitler gained power. Rubashov was to purge and reorganise the German communists. He met with Richard, a young German communist cell leader who had distributed material contrary to the Party line. In a museum, underneath a picture of the Pietà, Rubashov explains to Richard that he has violated Party discipline, become "objectively harmful", and must be expelled from the Party. A Gestapo man hovers in the background with his girlfriend on his arm. Too late, Richard realises that Rubashov has betrayed him to the secret police. He begs Rubashov not to "throw him to the wolves", but Rubashov leaves him quickly. Getting into a taxicab, he realises that the taxicab driver is also a communist. The taxicab driver, implied to be a communist, offers to give him free fare, but Rubashov pays the fare. As he travels by train, he dreams that Richard and the taxicab driver are trying to run him over with a train.

This scene introduces the second and third major themes of Darkness at Noon. The second, suggested repeatedly by the Pieta and other Christian imagery, is the contrast between the brutality and modernity of communism on the one hand, and the gentleness, simplicity, and tradition of Christianity. Although Koestler is not suggesting a return to Christian faith, he implies that communism is the worse of the two alternatives.

The third theme is the contrast between the trust of the rank and file communists, and the ruthlessness of the Party elite. The rank and file trust and admire men like Rubashov, but the elite betrays and uses them with little thought. As Rubashov confronts the immorality of his actions as a party chief, his abscessed tooth begins to bother him, sometimes reducing him to immobility.

Rubashov recalls being arrested soon after by the Gestapo and imprisoned for two years. Although repeatedly tortured, he never breaks down. After the Nazis finally release him, he returns to his country to a hero's welcome. Number One's increasing power makes him uncomfortable but he does not act in opposition; he requests a foreign assignment. Number One is suspicious but grants the request. Rubashov is sent to Belgium to enforce Party discipline among the dock workers. After the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935, the League of Nations and the Party condemned Italy and imposed an international embargo on strategic resources, especially oil, which the Italians needed. The Belgian dock workers are determined not to allow any shipments for Italy to pass through their port. As his government intends to supply the Italians with oil and other resources secretly, Rubashov must convince the dock workers that, despite the official policy, as communists they must unload the materials and not send them to the Italians.

Their cell leader, a German communist immigrant nicknamed Little Loewy, tells Rubashov his life's story. He is a communist who has sacrificed much for the Party, but is still completely dedicated. When all the workers have gathered, Rubashov explains the situation. They react with disgust and refuse his instructions. Several days later, Party publications denounce the entire cell by name, virtually guaranteeing arrest by the Belgian authorities, who were trying to suppress communism. Little Loewy hangs himself. Rubashov then begins a new assignment.

In the novel, after about a week in prison, he is brought in for the first examination or hearing, which is conducted by Ivanov, an old friend. Also a veteran of the Civil War, he is an Old Bolshevik who shares Rubashov's opinion of the Revolution. Rubashov had then convinced Ivanov not to commit suicide after his leg was amputated due to war wounds. Ivanov says that if he can persuade Rubashov to confess to the charges, he will have repaid his debt. With confession, Rubashov can lessen his sentence, to five or 10 years in a labour camp, instead of execution. He simply has to co-operate. The charges are hardly discussed, as both men understand they are not relevant. Rubashov says that he is "tired" and does not "want to play this kind of game anymore". Ivanov sends him back to his cell, asking him to think about it. Ivanov implies that Rubashov can perhaps live to see the socialist utopia they have both worked so hard to create, and gives Rubashov two weeks to think matters over.

The Second Hearing

The next section of the book begins with an entry in Rubashov's diary; he struggles to find his place and that of the other Old Bolsheviks, within the Marxist interpretation of history.

Ivanov and a junior examiner, Gletkin, discuss Rubashov's fate. Gletkin urges using harsh, physical methods to demoralise the prisoner and force his confession, while Ivanov insists that Rubashov will confess after realising it is the only "logical" thing to do, given his situation and also his past commitment to the party. Gletkin recalls that, during the collectivisation of the peasants, they could not be persuaded to surrender their individual crops until they were tortured (and killed). Since that helped enable the ultimate goal of a socialist utopia, it was both the logical and the virtuous thing to do. Ivanov is disgusted but cannot refute Gletkin's reasoning. Ivanov believes in taking harsh actions to achieve the goal, but he is troubled by the suffering he causes. Gletkin says the older man must not believe in the coming utopia. He characterises Ivanov as a cynic and claims to be an idealist.

Their conversation continues the theme of the new generation taking power over the old: Ivanov is portrayed as intellectual, ironical, and at bottom humane, while Gletkin is unsophisticated, straightforward, and unconcerned with others' suffering. Being also a Civil War veteran, Gletkin has his own experience of withstanding torture, yet still advocates its use. Ivanov has not been convinced by the younger man's arguments. Rubashov continues in solitary.

News is tapped through to Rubashov that a prisoner is about to be executed. The condemned man is Michael Bogrov, the one-time distinguished revolutionary naval commander, who had a personal friendship with Rubashov. As Bogrov is carried off crying and screaming, all the prisoners, as is their tradition, drum along the walls to signal their brotherhood. Bogrov, as he passes Rubashov's cell, despairingly calls out his name; Rubashov, having watched him pass by through the spy-hole in the door, is shocked at the pathetic figure Bogrov has become.

Some time later Ivanov visits Rubashov in his cell. He tells Rubashov that every aspect of Bogrov's execution had been orchestrated by Gletkin to weaken Rubashov's resolve, but that he (Ivanov) knows it will have the opposite effect. Ivanov tells Rubashov that he knows Rubashov will only confess if he resists his growing urge to sentimentality and instead remains rational, “[f]or when you have thought the whole thing to a conclusion – then, and only then, will you capitulate”. The two men have a discussion about politics and ethics. Afterwards Ivanov visits Gletkin in his office and insultingly tells him he was able to undo the damage that Gletkin's scheme would have done.

The Third Hearing and The Grammatical Fiction

Rubashov continues to write in his diary, his views very much in line with Ivanov's. He tells No. 402 that he intends to capitulate, and when No. 402 scolds him they get into a dispute over what honor is and break off contact with each other. Rubashov signs a letter to the state authorities in which he pledges "utterly to renounce [my] oppositional attitude and to denounce publicly [my] errors".

Gletkin takes over the interrogation of Rubashov, using physical stresses such as sleep deprivation and forcing Rubashov to sit under a glaring lamp for hours, to wear him down. Later, when Gletkin refers to Ivanov in the past tense, Rubashov inquires about it, and Gletkin informs him that Ivanov has been executed. Rubashov notices that news of Ivanov's fate has not made a meaningful impression on him, as he has evidently reached a state that precludes any deep emotion. Rubashov finally capitulates.

As he confesses to the false charges, Rubashov thinks of the many times he betrayed agents in the past: Richard, the young German; Little Loewy in Belgium; and Orlova, his secretary-mistress. He recognises that he is being treated with the same ruthlessness. His commitment to following his logic to its final conclusion—and his own lingering dedication to the Party—causes him to confess fully and publicly.

The final section of the novel begins with a four-line quotation ("Show us not the aim without the way...") by the German socialist Ferdinand Lassalle. Rubashov has a final tapped conversation with No. 402, and then is led away from his cell as the other prisoners, from behind the walls, drum in fraternity. The novel ends with Rubashov's execution.

Reception

Darkness at Noon was very successful, selling half a million copies in France alone.[31] Kingsley Martin described the novel as "one of the few books written in this epoch which will survive it".[32] The New York Times described Darkness at Noon as "a splendid novel, an effective explanation of the riddle of the Moscow treason trials...written with such dramatic power, with such warmth of feeling and with such persuasive simplicity that it is absorbing as melodrama".[32]

George Steiner said it was one of the few books that may have "changed history", while George Orwell, who reviewed the book for the New Statesman in 1941, stated:

Brilliant as this book is as a novel, and a piece of brilliant literature, it is probably most valuable as an interpretation of the Moscow "confessions" by someone with an inner knowledge of totalitarian methods. What was frightening about these trials was not the fact that they happened—for obviously such things are necessary in a totalitarian society—but the eagerness of Western intellectuals to justify them.[33]

Adaptations

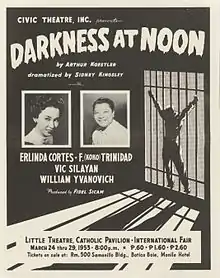

The novel was adapted as a stage play by Sidney Kingsley circa 1950, which was made into a 1955 television production on the American television series Producer’s Showcase.

Influence and legacy

Writers interested in the political struggles of the time followed Koestler and other Europeans closely. Orwell wrote, "Rubashov might be called Trotsky, Bukharin, Rakovsky or some other relatively civilised figure among the Old Bolsheviks".[34] In 1944, Orwell thought that the best political writing in English was being done by Europeans and other non-native British. His essay on Koestler discussed Darkness at Noon.[35] Orwell's Homage to Catalonia, about the Spanish Civil War, sold poorly; he decided after reviewing Darkness at Noon that fiction was the best way to describe totalitarianism, and wrote Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four.[31] When reviewing Nineteen Eighty-Four, Arthur Mizener said that Orwell drew on his feelings about Koestler's handling of Rubashov's confession when he wrote his extended section of the conversion of Winston Smith.[36]

In 1954, at the end of a long government inquiry and a show trial, Lucreţiu Pătrăşcanu, the former high-ranking Romanian Communist Party member and government official, was sentenced to death in Romania.[37][38] According to his collaborator Belu Zilber, Pătrăşcanu read Darkness at Noon in Paris while envoy to the 1946 Peace Conference, and took the book back to Romania.[37][38]

Both American and European communists considered Darkness at Noon to be anti-Stalinist and anti-USSR. In the 1940s, numerous scriptwriters in Hollywood were still communists, generally having been attracted to the party during the 1930s. According to Kenneth Lloyd Billingsley in an article published in 2000, the communists considered Koestler's novel important enough to prevent its being adapted for movies; the writer Dalton Trumbo "bragged" about his success in that to the newspaper The Worker.[39]

U.S. Navy admiral James Stockdale used the novel's title as a code to his wife and the U.S. government to fool his North Vietnamese captors' censors when he wrote as a POW during the Vietnam War. He signaled the torture of American POW's by communist North Vietnam: "One thinks of Vietnam as a tropical country, but in January the rains came, and there was cold and darkness, even at noon." His wife contacted U.S. Naval Intelligence and Stockdale confirmed in code in other letters that they were being tortured.[40]

At the height of the media attention during the Clinton–Lewinsky scandal, U.S. President Bill Clinton reportedly referred to Koestler's novel, telling an aide "I feel like a character in the novel Darkness at Noon" and "I am surrounded by an oppressive force that is creating a lie about me and I can't get the truth out."[41]

The novel is of special interest to historians of British propaganda, due to the heavy financial support that the novel secretly received from the Information Research Department (IRD), a covert branch of the UK Foreign Office dedicated to disinformation, pro-colonial, and anti-communist propaganda.[42][43] The IRD bought thousands of copies to inflate sales statistics, and also used British embassies to translate and distribute the novel to be used as Cold War propaganda.[44][45][46]

Theory of the masses

Rubashov resigns himself to the reality that people are not capable of self-governance nor even of steering a democratic government to their own benefit. This he asserts is true for a period of time following technological advancements—a period in which people as a group have yet to learn to adapt to and harness, or at least respond to the technological advancements in a way that actually benefits them. Until this period of adaptation runs its course, Rubashov comes to accept that a totalitarian government is perhaps not unjustified as people would only steer society to their own detriment anyway. Having reached this conclusion, Rubashov resigns himself to execution without defending himself against charges of treason.

Every jump of technical progress leaves the relative intellectual development of the masses a step behind, and thus causes a fall in the political-maturity thermometer. It takes sometimes tens of years, sometimes generations, for a people's level of understanding gradually to adapt itself to the changed state of affairs, until it has recovered the same capacity for self-government as it had already possessed at a lower stage of civilization. (Hardy translation)

And so every leap of technical progress brings with it a relative intellectual regression of the masses, a decline in their political maturity. At times it may take decades or even generations before the collective consciousness gradually catches up to the changed order and regains the capacity to govern itself that it had formerly possessed at a lower stage of civilization. (Boehm translation)

― Arthur Koestler, Darkness at Noon

Footnotes

- The German manuscript was lost until 2015; the first published version was an English translation. Subsequent published translations until 2019, including the German version, derive from the English text.[1]

References

- Scammell, Michael (7 April 2016). "A Different 'Darkness at Noon'". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- Kirsch, Adam (23 September 2019). "The Desperate Plight Behind 'Darkness at Noon'". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X.

- "Long missing original manuscript of the novel "Darkness at Noon" by Koestler has been found" Archived 25 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Press release by the University of Kassel, 10 August 2015.

- "Neuerscheinungen, Elsinor Verlag". Archived from the original on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- After 80 years, Darkness at Noon's original text is finally translated The Guardian, 2019.

- Koestler, Arthur (17 September 2019) [1941]. "Introduction by Michael Scammell". Darkness at Noon. Simon and Schuster. p. xvi, xvii. ISBN 978-1-9821-3522-5.

- "The Eerily Prescient Lessons of Darkness at Noon"

- Arthur and Cynthia Koestler, Stranger on the Square, edited by Harold Harris, London: Hutchinson, 1984, pp. 20–22.

- Koestler, Arthur (17 September 2019) [1941]. "Introduction by Michael Scammell". Darkness at Noon. Simon and Schuster. p. xiii. ISBN 978-1-9821-3522-5.

- A&C Koestler (1984), pp. 20–22

- Anne Applebaum, "Did the Death of Communism Take Koestler And Other Literary Figures With It?" Review of Michael Scammell, Koestler: The Literary and Political Odyssey of a Twentieth-Century Skeptic, in The New York Review of Books (11 Feb. 2010), reprinted in Huffington Post (28 Mar. 2010, updated 25 May 2011)

- Koestler, Arthur (1941). Darkness at Noon. Scribner. pp. ii.

- Calder, Jenni (1968). Chronicles of Conscience: A Study of George Orwell and Arthur Koestler. Martin Secker & Warburg Limited. p. 127.

- Koestler, Arthur (1945). The Yogi and the Commissar. Jonathan Cape Ltd. p. 148.

- Orwell, Sonia, ed. (1968). The Collected Essays, Journalism, and Letters of George Orwell, vol 3. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World. p. 239.

- Koestler (1941), Darkness, p. 27.

- Koestler (1941), Darkness, pp. 125–126.

- Koestler (1941), Darkness, p. 57.

- Koestler (1941), Darkness, p. 15.

- Koestler (1941), Darkness, p. 59

- Koestler (1941), Darkness, pp. 189, 212.

- Koestler (1941). Darkness. p. 4.

- Koestler (1941), Darkness, pp. 9–10.

- Koestler (1941). Darkness. pp. 2, 12.

- Koestler (1941), Darkness, pp. 25–30

- Koestler (1941), Darkness, p. 249

- Koestler (1941), Darkness, p. 178.

- Koestler (1941), Darkness, p. 51.

- Koestler (1941), Darkness, pp. 47, 75, 89.

- Koestler (1941), Darkness, pp. 161–163.

- Dalrymple, William. "Novel explosives of the Cold War". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Alt URL The first two of these links name Nicholas Shakespeare as the author; the third names William Dalrymple.

- Kati Marton, The Great Escape: Nine Jews who Fled Hitler and Changed the World. Simon and Schuster, 2006. ISBN 0743261151 (pp. 139–140).

- "The Untouched Legacy of Arthur Koestler and George Orwell". 24 February 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- "Arthur Koestler - Essay". The Complete Works of George Orwell. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- George Orwell, "Arthur Koestler (1944)" Archived 23 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine, in Collected Essays, (1944), ebooks at University of Adelaide, accessed 25 June 2012

- Arthur Mizener, "Truth Maybe, Not Fiction," The Kenyon Review, Vol. 1, No. 4 (Autumn 1949): 685.

- (in Romanian) Stelian Tănase, "Belu Zilber. Part III" (fragments of O istorie a comunismului românesc interbelic, "A History of Romanian Interwar Communism") Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, in Revista 22, Nr.702, August 2003

- Vladimir Tismăneanu, Stalinism for All Seasons: A Political History of Romanian Communism, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2003, ISBN 0-520-23747-1 pp. 75, 114.

- Kenneth Lloyd Billingsley, "Hollywood's Missing Movies: Why American Films Have Ignored Life under Communism" Archived 12 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine, in Reason, June 2000.

- Jane Meredith Adams, "In Love And War—and Now In Politics", Chicago Tribune, 30 October 1992.

- The Presidents: Clinton, program transcript, American Experience, PBS.

- Wilford, Hugh (2013). The CIA, the British Left and the Cold War: Calling the Tune?. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 58.

- Blotch, Jonathan; Fitzgerald, Patrick (1983). British Intelligence and Covert Action: Africa, Middle-East and Europe since 1945. London: Junction Books. p. 93.

- Defty, Andrew (2005). Britain, America and Anti-Communist Propaganda 1945-1953: The Information Research Department. eBook version: Routledge. p. 87.

- Jenks, John (2006). British Propaganda and News Media in the Cold War. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 64.

- Mitter, Rana; Major, Patrick (2005). Across the Block: Cold War Cultural and Social History. Taylor & Francis e-library: Frank Cass and Company Limited. p. 125.

External links

- Copy of Book on the Internet Archive. 1948.

- Harold Strauss, "The Riddle of Moscow's Trials" (book review of Darkness at Noon), The New York Times, 25 May 1941