Darlingtonia californica

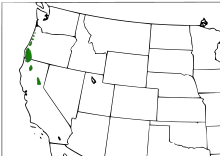

Darlingtonia californica /dɑːrlɪŋˈtoʊniə kælɪˈfɔːrnɪkə/, also called the California pitcher plant, cobra lily, or cobra plant, is a species of carnivorous plant. It is the sole member of the genus Darlingtonia in the family Sarraceniaceae. This pitcher plant is native to Northern California and Oregon, US, growing in bogs and seeps with cold running water usually on serpentine soils. This plant is designated as uncommon due to its rarity in the field.[2]

| Cobra lily | |

|---|---|

| |

| Darlingtonia's translucent leaves confuse insects trying to escape. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Ericales |

| Family: | Sarraceniaceae |

| Genus: | Darlingtonia Torr. (1853) |

| Species: | D. californica |

| Binomial name | |

| Darlingtonia californica Torr. | |

| |

| Darlingtonia distribution | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The name "cobra lily" stems from the resemblance of its tubular leaves to a rearing cobra, complete with a forked leaf – ranging from yellow to purplish-green – that resemble fangs or a serpent's tongue.

The plant was discovered during the Wilkes Expedition in 1841 by the botanist William D. Brackenridge at Mount Shasta. In 1853 it was described by John Torrey, who named the genus Darlingtonia after the Philadelphian botanist William Darlington (1782–1863).

Cultivation in the UK has gained the plant the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[3][4]

Biology

The cobra plant is not just restricted to nutrient-poor acidic bogs and seepage slopes, but many colonies actually thrive in ultramafic soils, which are in fact basic soils, within its range. In common with most carnivorous plants, the cobra lily is adapted to supplementing its nitrogen requirements through carnivory, which helps to compensate for the lack of available nitrogen in such habitats.

Root system

Because many carnivorous species live in hostile environments, their root systems are commonly as highly modified as their leaves. Darlingtonia californica is no exception. The cobra lily has a very large and rambling root system when compared to those of other carnivorous plants in the family Sarraceniaceae.[5] The cobra lily is able to survive fire by regenerating from its roots, but despite this important role the roots are very delicate organs. While the temperatures in much of the species's range can exceed 25 °C (77 °F), their roots die back after exposure to temperatures not much higher than 10 °C (50 °F) . Temperature plays a large part in the functioning of all plants, but it is very rare for individual organs to have such different temperature tolerances. The physiological mechanisms and evolutionary benefits of this discrepancy are not fully understood, however, in habitat the plants are normally found growing out of cold seeps, and this behavior would cause the plant to only expend energy growing roots in the direction of cold subsurface water sources. The reason for this extraordinary sensitivity of the roots to high temperatures is currently believed to be caused by a very low and limited optimal temperature of the ion pumps in root cells [5][6]

Modern cultivation efforts in breeding and selecting plants that can withstand higher temperatures without the roots dying back have met with significant success. As a result, there are several cultivars available as commercial house or garden plants which are more tolerant of higher temperatures. Many wild populations grow in serpentine (ultramafic) soils which are toxic to most green plants. Populations found growing on serpentine can withstand soil temperatures above 80 °F based on field studies of various cobra lily populations in Oregon, most of which are found growing on slopes composed of serpentine with cold subsurface water flow. The plants can suffer from root rot in cultivation if grown in stagnant, standing water and tend to thrive in areas where cold subsurface water slowly flows underground around their roots. It is not currently understood why the plants can withstand higher soil temperatures when found growing on serpentine soils.[7][8]

Pitcher mechanisms

The cobra lily is unique among the three genera of American pitcher plants. It does not trap rainwater in its pitcher. Instead, it regulates the level of water inside physiologically by releasing or absorbing water into the trap that has been pumped up from the roots. It was once believed that this species of pitcher plant did not produce any digestive enzymes and relied on symbiotic bacteria and protozoa to break down the captured insects into easily absorbed nutrients. However, recent studies have indicated that Darlingtonia secretes at least one proteolytic enzyme that digests captured prey.[9]: 61 The cells that absorb nutrients from the inside of the pitcher are the same as those on the roots that absorb soil nutrients. The efficiency of the plant's trapping ability is attested to by its leaves and pitchers, which are, more often than not, full of insects and their remains.[9]: 58

The slippery walls and hairs of the pitcher tube prevent trapped prey from escaping. In addition to the lubricating secretions and downward-pointing hairs common to all North American pitcher plants to force their prey into the trap, this species uses its curled operculum (hood) to hide the tiny exit hole from trapped insects and offers multiple translucent false exits. Upon trying many times to escape via the false exits, the insect will tire and fall down into the trap. Other species that use a low-hanging hood to hide the exit hole include the parrot pitcher plant, Sarracenia psittacina and the hooded pitcher plant, Sarracenia minor. S. psittacina also forms a curled operculum, while S. minor uses a leaf that is folded over the entrance. A misconception about Darlingtonia is that its forked tongue is an adaption to trap insects. However, a study done by American Journal of Botany determined that removal of the tongue does not affect prey biomass.[10]

Pollination

A remaining mystery surrounding the cobra lily is its means of pollination. Its flower is unusually shaped and complex, typically a sign of a close pollinator-plant specialization. The flower is yellowish purple in color and grows on a stalk which is slightly taller than the pitcher leaves. It has five sepals, green in color, which are longer than the red-veined petals. It is generally expected that the pollinator is either a fly or bee attracted to the flower's unpleasant smell or some nocturnal insect.[11]

A new study suggests that it may be melittophilous after observing a miner bee species (Andrena nigrihirta). Pollinating by hand yielded poor results, therefore, melittophilous seems likely considering the complexity of the fruit. According to the study, "Observations of A. nigrihirta on flowers revealed that the shape and orientation of D. californica's ovary and petals promote stigma contact both when pollinators enter and exit a flower, contrary to previous thought. Our findings provide evidence that D. californica is melittophilous". Furthermore, Darlingtonia was pollen-limited in all five plants observed. However, in the case of male absence, Darlingtonia was still able to reproduce suggesting that self pollination may play a role as well.[12] It seems likely that both occur and only bolsters the reputation of hardiness in the wild.[13]

Infraspecific taxa

Two infraspecific taxa are recognized:[14]

Cultivation

Darlingtonia californica can be a difficult carnivorous plant to keep in cultivation, as they require specific environmental conditions.[15] They prefer cool to warm day-time temperatures and cold or cool night-time temperatures. Cobra lilies typically grow in bogs or streambanks that are fed by cold mountain water, and grow best when the roots are kept cooler than the rest of the plant.[15] It is best to mimic these conditions in cultivation, and water the plants with cold, purified water. On hot days, it helps to place ice cubes of purified water on the soil surface. They prefer sunny conditions if in a humid, warm location, and prefer part-shade if humidity is low or fluctuates often. Plants can adapt to low humidity conditions, but optimum growth occurs under reasonable humidity.

Growing cobra lilies from seed is extremely slow and cobra seedlings are difficult to maintain, so these plants are best propagated from the long stolons they grow in late winter and spring. When a minute cobra plant is visible at the end of the stolon (usually in mid to late spring), the whole stolon may be cut into sections a few inches long, each with a few roots attached. Lay these upon cool, moist, shredded long-fibered sphagnum moss and place in a humid location with bright light. In many weeks, cobra plants will protrude from each section of stolon.

Like many other carnivorous plants of temperate regions, cobra lilies require a cold winter dormancy in order to live long-term. Plants die down to their rhizomes in frigid winters and will maintain their leaves in cool winters during their dormancy period. This period lasts from 3 to 5 months during the year, and all growth stops. As spring approaches, mature plants may send up a single, nodding flower, and a few weeks later the plant will send up a few large pitchers. The plant will continue to produce pitchers throughout the summer, however much smaller than the early spring pitchers.

Many carnivorous plant enthusiasts have succeeded in cultivating these plants, and have developed or discovered three color morphs: all green, all red, and red-green bicolor.

Wild-type plants are all green in moderate light and bicolor in intense sunlight.

References

- Schnell, D.; Catling, P.; Folkerts, G.; Frost, C.; Gardner, R.; et al. (2000). "Darlingtonia californica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2000: e.T39714A10259059. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2000.RLTS.T39714A10259059.en. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- The Jepson Herbarium – University of California, Berkeley

- "RHS Plantfinder – Darlingtonia californica". Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- "AGM Plants – Ornamental" (PDF). Royal Horticultural Society. July 2017. p. 16. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Adlassnig, W.; Peroutka, M.; Lambers, H.; Lichtscheidl, I. K. (2005). "The roots of carnivorous plants" (PDF). Plant and Soil. 274 (1–2): 127–140. doi:10.1007/s11104-004-2754-2. S2CID 5038696. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-05-31.

- Ziemer, Robert R. "Some field observations of Darlingtonia and Pinguicula". Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 2(2): 25-27. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- "Growing Darlingtonia californica". International Carnivorous Plant Society. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- "Serpent of the Siskiyous - Darlingtonia californica". YouTube. 2022-06-08. Retrieved 2022-06-10.

- Pietropaolo, James (2005). Carnivorous Plants of the World. Timber Press. ISBN 0-88192-356-7.

- Armitage, David. W (2016). "The cobras tongue: rethinking the function of the 'fishtail appendage' on the pitcher plant Darlingtonia californica". American Journal of Botany. 103 (4): 780–785. doi:10.3732/ajb.1500524. PMID 27033318.

- John Brittnacher with help from Harry Tryon December 2011 Latest update January 2020 ©International Carnivorous Plant Society https://www.carnivorousplants.org/grow/guides/Darlingtonia

- George A. Meindl and Michael R. Mesler "Pollination Biology of Darlingtonia californica (Sarraceniaceae), the California Pitcher Plant," Madroño 58(1), 22-31, (31 August 2011). https://doi.org/10.3120/0024-9637-58.1.22 https://bioone.org/journals/madro%C3%B1o/volume-58/issue-1/0024-9637-58.1.22/Pollination-Biology-of-Darlingtonia-californica-Sarraceniaceae-the-California-Pitcher-Plant/10.3120/0024-9637-58.1.22.short

- Brittnacher, John; Tryon, Harry (Jan 2020). "Growing Darlingtonia californica". International Carnivorous Plant Society. Retrieved 2021-03-18.

- McPherson, S. & D. Schnell 2011. Sarraceniaceae of North America. Redfern Natural History Productions Ltd., Poole.

- "Darlingtonia californica". fs.fed.us. Retrieved 2019-03-11.

External links

- Calflora Database: Darlingtonia californica (California pitcherplant)

- USDA Plants Profile for Darlingtonia californica (California pitcherplant)

- Darlingtonia State Natural Site

- Botanical Society of America, Darlingtonia californica – the cobra lily Archived 2014-05-19 at the Wayback Machine

- U.C. Photos gallery – Darlingtonia californica

- RHS Gardening – Darlingtonia californica

- Growing Darlingtonia californica – ICPS