Dassault-Breguet Super Étendard

The Dassault-Breguet Super Étendard (Étendard is French for "battle flag", cognate to English "standard") is a French carrier-borne strike fighter aircraft designed by Dassault-Breguet for service with the French Navy.

| Super Étendard | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| A Super Étendard at RIAT in 2005. | |

| Role | Strike fighter |

| National origin | France |

| Manufacturer | Dassault-Breguet |

| First flight | 28 October 1974 |

| Introduction | June 1978 |

| Retired | July 2016 (French Navy) |

| Status | In Limited service |

| Primary users | French Naval Aviation (historical) Argentine Naval Aviation (Limited service) Iraqi Air Force (historical) |

| Produced | 1974–1983 |

| Number built | 85 |

| Developed from | Dassault Étendard IV |

The aircraft is an advanced development of the Étendard IVM, which it replaced. The Super Étendard first flew in October 1974 and entered French service in June 1978. French Super Étendards have served in several conflicts such as the Kosovo war, the war in Afghanistan and the military intervention in Libya.

The Super Étendard was also operated by Iraq (on a temporary lease) and Argentina, which both deployed the aircraft during wartime. Argentina's Navy use of the Super Étendard and the Exocet missile during the 1982 Falklands War led to the aircraft gaining considerable popular recognition. The Super Étendard was used by Iraq to attack oil tankers and merchant shipping in the Persian Gulf during the Iraq-Iran War. In French service, the Super Étendard was replaced by the Dassault Rafale in 2016.[1]

Development

The Super Étendard is a development of the earlier Étendard IVM which had been developed in the 1950s. The Étendard IVM was originally to have been replaced by a navalised version of the SEPECAT Jaguar, designated as the Jaguar M; however the Jaguar M project was stalled by a combination of political problems and issues experienced during trial deployments on board carriers. Specifically, the Jaguar M had suffered handling problems when being flown on a single engine and a poor throttle response time that made landing back on a carrier after an engine failure difficult.[2] In 1973, all development work on the Jaguar M was formally cancelled by the French government.[3]

There were several proposed aircraft to replace the Jaguar M, including the LTV A-7 Corsair II and the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk. Dassault pulled some strings with the French government and produced its own proposal to meet the requirement.[4] According to Bill Gunston and Peter Gilchrist, Dassault had played a significant role in the cancellation of the Jaguar M with the aim of creating a vacancy for their own proposal – the Super Étendard.[5] The Super Étendard was essentially an improved version of the existing Étendard IVM, outfitted with a more powerful engine, a new wing and improved avionics. Dassault sold its plane as the only fully French-made candidate, and as cheaper than the other contestants, using modern technology already proven in existing Dassault planes. Dassault's Super Étendard proposal was accepted by the French Navy in 1973, leading to a series of prototypes being quickly assembled.[6]

The first of three prototypes to be built, an Étendard IVM which had been modified with the new engine and some of the new avionics,[6] made its maiden flight on 28 October 1974.[7][8][9] The original intention of the French Navy was to order a total of 100 Super Étendards, however the order placed was for 60 of the new model with options for a further 20; further budget cuts and an escalation in the aircraft's per unit price eventually led to only 71 Super Étendards being purchased.[9] Dassault began making deliveries of the type to the French Navy in June 1978.[7][10]

In the first year of production, 15 Super Étendards were produced for the French Navy, allowing the formation of the first squadron in 1979. Dassault produced the aircraft at a rough rate of two per month.[11]

The Argentine Navy was the only export customer. Argentina placed an order for 14 aircraft to meet their requirements for a capable new fighter that could operate from their sole aircraft carrier.[7] In 1983, all manufacturing activity was completed, the last delivery to the French Navy taking place that year.[9][12]

Design

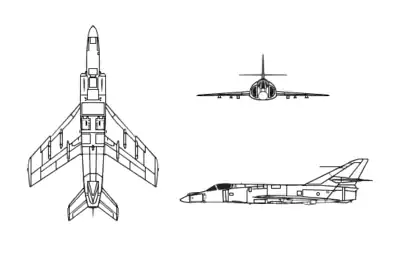

The Super Étendard is a small, single-engined, mid-winged aircraft with an all-metal structure. Both the wings and tailplane are swept, with the folding wings having a sweepback of about 45 degrees, while the aircraft is powered by a non-afterburning SNECMA Atar 8K-50 turbojet with a rating of 49 kN (11,025 lbf). Its performance was not much better than the Étendard IV, but its avionics were significantly improved.

The main new weapon of the Super Étendard was the French anti-shipping missile, the Aérospatiale AM 39 Exocet.[6] The aircraft had a Thomson-CSF Agave radar which, amongst other functions, was essential to launch the Exocet missile.[6] One of the major technical advances of the Super Étendard was its onboard UAT-40 central computer; this managed most mission-critical systems, integrating navigational data and functions, radar information and display, and weapons targeting and controls.[13]

In the 1990s, significant modifications and upgrades were made to the type, including an updated UAT-90 computer and a new Thomson-CSF Anemone radar which provided nearly double the range of the previous Agave radar.[14] Other upgrades at this time included an extensively redesigned cockpit with HOTAS controls, and airframe life-extension work was undertaken; a total of 48 aircraft received these upgrades, at a rate of 15 per year.[14] During the 2000s, further improvements included significantly improved self-defence ECM capability to better evade enemy detection and attacks,[15] cockpit compatibility with night vision goggles, a new inertial data system partly integrating GPS, and compatibility with the Damocles Laser designator pod.[14]

The Super Étendard could also deploy tactical nuclear weapons;[16] initially these were unguided gravity bombs only, however, during the 1990s the Super Étendard was extensively upgraded, enabling the deployment of the Air-Sol Moyenne Portée, a ramjet-powered air-launched nuclear missile.[6] The aircraft was also refitted with the ability to operate a range of laser-guided bombs and, to enable the type to replace the retiring Étendard IV in the reconnaissance mission, the Super Étendard was fitted to carry a specialist reconnaissance pod as well.[15] However, the aircraft is unable to perform naval landings without jettisoning unexpended ordnance.[14]

Operational history

Argentina

The Argentine Naval Aviation decided to buy 14 Super Étendards in 1979 after the United States put an arms embargo in place, due to the Dirty War and refused to supply spare parts for Argentina's fleet of A-4Q Skyhawks. Between August and November 1981, five Super Étendards and five anti-ship sea-skimming Exocet missiles were shipped to Argentina.[17] The Super Étendards, armed with Exocet anti-ship missiles played a key role in the Falklands War between Argentina and the United Kingdom in 1982. The 2nd Naval Squadron was stationed at the Río Grande, Tierra del Fuego naval air base; during the conflict. The threat posed to British naval forces led to the planning of Operation Mikado and other proposed infiltration missions to raid the airbase, aiming to destroy the Super Étendards to prevent their use.[18][19] A total of four Super Étendards were operational during the conflict.[9]

A first attempt to attack the British fleet was made on 2 May 1982, but this was abandoned due to in-flight-refuelling problems.[20] On 4 May, two Super Étendards, guided by a Lockheed P-2H Neptune, each launched one Exocet at the British destroyer HMS Sheffield, with one missile crippling Sheffield.[20][21] On 25 May, another attack by two Super Étendards resulted in two missiles hitting the merchant ship Atlantic Conveyor, which was carrying several helicopters and other supplies to the front line.[21][22][23] The Exocets that struck Atlantic Conveyor had been inadvertently redirected by decoy chaff deployed as a defensive measure by other ships;[24] Both Sheffield and Atlantic Conveyor sank whilst under tow some days later following these Exocet strikes.[25]

On May 30 two Super Étendards, one carrying Argentina's last remaining Exocet, escorted by four A-4C Skyhawks each with two 500lb bombs, took off to attack the carrier HMS Invincible. The missile was shot down by a Sea Dart fired by HMS Exeter.

Following the end of the conflict, by 1984 Argentina had received all the 14 Super Étendards ordered, and Exocets with which to arm them.[26] Super Étendards performed qualifications on the aircraft carrier ARA 25 de Mayo until the ship's final retirement.[27] Since 1993, Argentine pilots have practised on board the neighbouring Brazilian Navy's aircraft carrier São Paulo. Touch-and-go landing exercises were also common on US Navy carriers during Gringo-Gaucho manoeuvres and joint exercises.[28]

In 2009, an agreement was signed between Argentina and France to upgrade Argentina's remaining fleet of Super Étendards.[29] An earlier proposal to acquire former French Naval Super Étendards was rejected due to high levels of accumulated flight hours; instead equipment and hardware would be removed from retiring French airframes and installed into Argentine aircraft, effectively upgrading them to the Super Étendard Modernisé (SEM) standard.[30] By March 2014, while the Argentine Navy continued to seek the upgrade kits for 10 of its 11 remaining Super Étendards; this ambition appears to have been complicated by several factors, France has been non-committal regarding the sought sale; critically, political developments between France and the UK may potentially allow the UK to obstruct the supply of military equipment to Argentina such as the upgrade kits and the Exocet missile.[31]

In 2017 five Super Étendard Modernisé were purchased from France to bolster the fleet at a cost of €12.5 million, along with a simulator, eight spare engines, and a large batch of spares and tooling.[32][33][34][35] However, while these aircraft were delivered in 2019, as of 2020 they still await the delivery of key spare parts and may not be in operational service for a further two years.[36] In 2021, it was reported that the aircraft also remained non-operational due to problems obtaining components for the Martin Baker ejection seats manufactured in the U.K.. As a result, alternative parts were being sought in the United States.[37] In early 2022, it was reported that the spare parts problem remained unresolved and the aircraft remained in storage.[38]

France

Deliveries of the Super Étendard to the French Navy started in 1978, with the first squadron, Flottille 11F becoming operational in February 1979. As they offered no air combat capabilities France had to extend useful life of its Crusaders fighters, as no replacement option was found.

In total, three operational squadrons and a training unit were equipped with the Super Étendard.[6] The Super Étendards would operate from both of France's aircraft carriers at that time, Clemenceau and Foch; either carrier's air wing typically comprised 16 Super Étendards, 10 F-8 Crusaders, 3 Étendard IVPs, 7 Breguet Alizé anti-submarine aircraft, as well as numerous helicopters.[39]

The first fighting operational missions took place in Lebanon during Operation Olifant. On 22 September 1983, French Navy Super Étendards operating from Foch bombed and destroyed Syrian forces positions after a few artillery rounds were fired at the French peace keepers.[40] On November 10, a Super Étendard dodged a Syrian SA-7 shoulder-launched missile near Bourj el-Barajneh while flying over Druze positions.[41] On 17 November 1983, the same airplanes attacked and destroyed an Islamic Amal training camp in Baalbeck after a terrorist attack on French paratroopers in Beirut.[42]

From 1991, the original pure attack Étendard IVMs were withdrawn from French service;[43] though the reconnaissance version of the Étendard IV, the IVP, remained in service until July 2000.[44] In response, the Super Étendards underwent a series of upgrades throughout the 1990s to add new capabilities and update existing systems for use in the modern battlefield. Designated Super Étendard Modernisé (SEM), the first combat missions for the type came during NATO's Allied Force operations over Serbia in 1999 flying 400 combat missions. An Étendard IVPM from the Flottile 16.F was hit by a Serb SAM on 15 April 1994, while flying a reconnaissance mission over Gorazde, Bosnia, as part of Operation Deny Flight. The pilot managed to safely land on Clemenceau despite heavy damage on its tailpipe, elevators and fin.[45]

The SEM also flew strike missions in Operation Enduring Freedom. Mission Héraclès starting 21 November 2001 saw the deployment of the aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle and its Super Étendards in Afghanistan. Operation Anaconda, starting on 2 March 2002 saw extensive use of the Super Étendard in support of French and allied ground troops. Super Étendards returned to operations over Afghanistan in 2004, 2006, 2007, 2008 and 2010–2011. One of their main roles was to carry laser designation pods to illuminate targets for Dassault Rafales.[46]

In March 2011, Étendards were deployed as a part of Task Force 473, during France's Opération Harmattan in support of UN resolution 1973 during the Libyan conflict.[47] They were paired again with Dassault Rafales on interdiction missions.[48] The final Super Étendards in French naval aviation were in one "flottille" (squadron) called flottille 17F. All Super Étendards were retired from French service on 12 July 2016 to be replaced by the Dassault Rafale M, 42 years after the subsonic attack jet performed its first flight.[1] The Super Étendard's last operational deployment from Charles de Gaulle was in support of Opération Chammal against Islamic State militants in Iraq and Syria, which began in late 2015.[49] On 16 March 2016, the aircraft undertook its final launch from Charles de Gaulle ahead of its final withdrawal from service in July.

Iraq

A total of five Super Étendards were loaned to Iraq in 1983 while the country was waiting for deliveries of Agave-equipped Dassault Mirage F1s capable of launching Exocet missiles that had been ordered; the first of these aircraft arrived in Iraq on 8 October 1983.[50] The provision of Super Étendards to Iraq was politically controversial, the United States and Iraq's neighbour Iran were vocal in their opposition while Saudi Arabia supported the loan; the aircraft were seen as an influential factor in the 1980–88 Iraq-Iran War as they could launch Exocet strikes on Iranian merchant shipping traversing the Persian Gulf.[51][52] The Super Étendards began maritime operations over Persian Gulf in March 1984; a total of 34 attacks were carried out on Iranian shipping through the rest of 1984.[53] Tankers of any nationality that were carrying Iranian crude oil were also subject to Iraqi attacks.[54]

Iraq typically deployed the Super Étendards in pairs, escorted by Mirage F1 fighters from bases in Southern Iraq; once inside the mission zone, the Super Étendards would search for targets using their onboard radar and engage suspected tankers at long range without visual identification.[55] While tankers would typically be struck by a launched Exocet, they were often only lightly damaged.[56] On 2 April 1984, an Iraqi Super Étendard was reportedly shot down by a AIM-7E-2 missile fired by an Iranian F-4 Phantom II piloted by Khosrow Adibi over Kharg Island.[57] Separately, on 26 July and 7 August 1984, claims of Super Étendard losses to Iranian Grumman F-14 Tomcats were reported.[58] Iran claimed a total of three Super Étendards to have been shot down by Iranian interceptors; France stated that four of the five leased aircraft were returned to France in 1985.[58]

Operators

- Argentine Navy originally received 14 aircraft, of which few are currently operational. A further 5 ex-French navy aircraft (Modernisé spec) were acquired for operational service and training/spare parts in 2017;[59] these aircraft remain non-operational as of 2021.[37] On 17 May 2023, on the occasion of the 209th anniversary of the Argentine Navy, Argentinean Minister of Defense Jorge Taiana, announced the withdrawal from service of all the Super Étendards of the Aviación Naval Argentina.[60]

- French Navy received 71 aircraft; retired from active service on 12 July 2016.[1]

- Iraqi Air Force was loaned five French aircraft between 1983 and 1985; one was lost during the Iran–Iraq War, the remainder returned to France in 1985.[61]

Specifications

Data from All The World's Aircraft 1982–83;[16]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 14.31 m (46 ft 11 in)

- Wingspan: 9.6 m (31 ft 6 in)

- Height: 3.86 m (12 ft 8 in)

- Wing area: 28.4 m2 (306 sq ft)

- Empty weight: 6,500 kg (14,330 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 12,000 kg (26,455 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × Snecma Atar 8K-50 turbojet, 49 kN (11,000 lbf) thrust

Performance

- Maximum speed: 1,205 km/h (749 mph, 651 kn) [62]

- Range: 1,820 km (1,130 mi, 980 nmi) [63]

- Combat range: 850 km (530 mi, 460 nmi) with one AM39 Exocet missile on one wing pylon and one drop tank on opposite pylon, hi-lo-hi profile

- Service ceiling: 13,700 m (44,900 ft)

- Rate of climb: 100 m/s (20,000 ft/min) [64]

- Wing loading: 423 kg/m2 (87 lb/sq ft)

- Thrust/weight: 0.77 (Empty), 0.42 (MTOW)

Armament

- Guns: 2× 30 mm (1.18 in) DEFA 552 cannons with 125 rounds per gun

- Hardpoints: 4× underwing and 2× under-fuselage with a capacity of 2,100 kg (4,600 lb) maximum

- Rockets: 4× Matra rocket pods with 18× SNEB 68 mm rockets each

- Missiles:

- 1× AM-39 Exocet Anti-shipping missile or

- 1× Air-Sol Moyenne Portée nuclear armed missile or

- 2× AS-30L or

- 2× Matra Magic Air-to-air missile

- Bombs: Conventional unguided or laser-guided bombs, provision for 1 × AN-52 free-fall nuclear bomb, provision for "buddy" air refuelling pod[65]

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

- Iranian aerial victories during the Iran-Iraq war

- List of fighter aircraft

- List of military aircraft of France

Current squadrons

Notes

- "Les Super Etendard français retirés du service" [The French Super Etendard retires from service] (in French). Mer et Marine. 13 July 2016.

- Jackson 1992, p. 77.

- Bowman 2007, p. 26.

- Information, Reed Business (14 December 1972), "An Embarrassment of Aeroplanes", New Scientist, vol. 56, no. 824, pp. 660–61

{{citation}}:|first1=has generic name (help). - Gunston and Gilchrist 1993, p. 169.

- Grolleau 2003, p. 40.

- Taylor 1982, p. 65.

- Polmar 2006, p. 330.

- Gunston and Gilchrist 1993, p. 170.

- Friedman 2006, p. 159.

- "France's Aerospace Industry – Programme by Programme." Flight International, 4 November 1978. p. 1647.

- Michell 1994, p. 65.

- Friedman 2006, pp. 159–60.

- Friedman 2006, p. 160.

- Grolleau 2003, pp. 40–41.

- Taylor 1982, pp. 65–66.

- Burden et al. 1986, p. 34.

- Smith, Michael (8 March 2002), "SAS 'suicide mission' to wipe out Exocets", The Daily Telegraph, London, ENG, UK.

- "Thatcher in the dark on sinking of Belgrano", The Times, London, ENG, UK, 27 June 2005.

- Burden 1986, p. 35.

- Huertas 1997, pp. 22–29.

- Burden 1986, p. 36

- Burden 1986, pp. 434, 438.

- Freedman 2005, p. 482.

- Freedman 2005, pp. 438, 482, 778.

- Freedman 2005, p. 701.

- Qualification Ops on YouTube

- Polmar 2006, pp. 329–30.

- Cooperación argentino-francesa en defensa [-Argentine-French defense cooperation] (news) (in Spanish), Argentine Ministry of Defence, 2 November 2011, archived from the original on 2011-07-18

- "Argentine Navy plans Super Étendard upgrade: Update." Jane's International Defence Review, 5 May 2009.

- Gonzalez, Diego (10 March 2014). "Argentine Super Etendard modernisation hits major snags". IHS Jane's Defence Weekly.

- Kraak, Jan (July 2017). "French Sale: Rafales, Mirage F1s and Jaguars". Air International. Vol. 93, no. 1. pp. 14–15. ISSN 0306-5634.

- "New Argentine Super Étendards". Air International. Vol. 93, no. 6. December 2017. p. 15. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Rivas, Santiago (14 May 2018). "Argentina finally buys five French Super Etendards". Janes.com. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- Charpentreau, Clément (17 May 2018). "Argentinian president approves lagging Super Etendard acquisition". Aerotime News Hub. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- "Los Super Étendard argentinos estarían operativos en dos años". Infodefensa - Noticias de defensa, industria, seguridad, armamento, ejércitos y tecnología de la defensa.

- "Argentina busca repuestos para los asientos eyectables de los Super Étendard Modernisé". Infodefensa - Noticias de defensa, industria, seguridad, armamento, ejércitos y tecnología de la defensa.

- "Argentine Navy warplanes still grounded due to lack of British-made spare parts". MercoPress.

- Jackson 2010, p. 76.

- Jackson 1986, p.66.

- Acig, archived from the original on 2013-10-07.

- Koven, Ronald. "France: Shiites Planned More Strikes." Boston Globe, 18 November 1983.

- Grolleau 2003, p.39.

- Grolleau 2003, pp. 39–40.

- Marie, Gaëtan (2016-11-07). "Dassault Etendard & Super Etendard". Gaëtan Marie's Aviation Profiles. Retrieved 2023-10-09.

- Wall, Robert (9 June 2008). "Super Étendards in Afghanistan". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- "Libye : première mission aérienne pour la TF 473" [Libya: first TF 473 aerial mission]. Opération Harmattan (in French). French Ministry of Defense. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- "Libye : point de situation opération Harmattan n°6" [Libya: status of operation Harmattan nº 6] (in French). French Ministry of Defense. Archived from the original on 2011-05-05. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- French Carrier Strike Group to Deploy to Eastern Mediterranean with Largest Airwing Ever – Navyrecognition.com, 16 November 2015

- Jackson 1986, p.69.

- "Étendards in Iraq since October 8." Flight International, 19 November 1983. p. 1342.

- Raj, Christopher S. "Shadow of Super Étendards over the Gulf." Strategic Analysis, 7(10). 1984. pp. 799–808.

- Kupersmith 1993, p. 29.

- Gunston and Gilchrist 1993, p. 171.

- Kupersmith 1993, p. 30.

- Kupersmith 1993, p. 43.

- Cooper and Bishop 2003, p. 88.

- Cooper 2004, p. 48.

- https://www.infobae.com/politica/2017/11/07/argentina-compro-cinco-aviones-militares-a-francia/ Argentina compró cinco aviones militares a Francia, Infobae, 7 November 2017

- "Argentina retired Super Etendard jets that sank two UK warships". 21 May 2023. Retrieved 2023-05-23.

- Gwertzman, Bernard (28 June 1983). "FRENCH AGREE TO LEND IRAQ PLANES TO USE IN FIRING ITS EXOCET MISSILES". New York Times. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- "Dassault Super Etendard Carrier-based Navy Strike Fighter Aircraft – France". MilitaryFactory. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- Flight International 25–31 May 2004, p. 53.

- Donald and Lake 1996, p. 142.

- Jackson 1986, p. 62.

Bibliography

- Burden, Rodney A., Michael A. Draper, Douglas A. Rough, Colin A Smith and David Wilton. Falklands: The Air War. Twickenham, UK: British Air Review Group, 1986. ISBN 0-906339-05-7.

- Carbonel, Jean-Christophe. French Secret Projects 1: Post War Fighters. Manchester, UK: Crecy Publishing, 2016 ISBN 978-1-91080-900-6

- Cooper, Tom. Iranian F-14 Tomcat Units in Combat. Osprey Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-841767-87-5.

- Donald, David and Jon Lake. Encyclopedia of World Military Aircraft. London, Aerospace Publishing, single volume ed., 1996. ISBN 1-874023-95-6.

- Freedman, Lawrence. The Official History of the Falklands Campaign: The 1982 Falklands War and Its Aftermath. Routledge, 2005. ISBN 0-714652-07-5.

- Friedman, Norman. The Naval Institute Guide to World Naval Weapon Systems, 5th ed. Naval Institute Press, 2006. ISBN 1-557502-62-5.

- Grolleau, Henri-Paul. "The Aéronavale Spearhead". Air International, January 2008, Vol 64 No 1. Stamford, UK: Key Publishing. ISSN 0306-5634, pp. 38–43.

- Gunston, Bill and Peter Gilchrist. Jet Bombers: From the Messerschmitt Me 262 to the Stealth B-2. Osprey, 1993. ISBN 1-85532-258-7.

- Hoyle, Craig. "World Air Forces Directory". Flight International, 13–19 December 2011, pp. 26–52.

- Huertas, Salvador Mafé. "Super Étendard in the Falklands: 2ª Escuadrilla Aeronaval de Caza y Ataque". Wings of Fame. Volume 8, 1997. London: Aerospace Publishing. ISBN 1-86184-008-X.

- Jackson, Paul (February 1986), "France's Superior Standard", Air International, Bromley, UK: Fine Scroll, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 49–69, ISSN 0306-5634.

- ——— (Winter 1992), "SEPECAT Jaguar", World Air Power Journal, London: Aerospace Publishing, vol. 11, pp. 52–111, ISBN 978-1-874023-96-8, ISSN 0959-7050.

- Jackson, Robert (2010), 101 Great Warships, Rosen, ISBN 978-1-4358-3596-2.

- Kupersmith, Douglas A (June 1993), The Failure of Third World Air Power (PDF), Air University Press.

- Michell, Simon (1994), Civil and Military Aircraft Upgrades 1994–95, Coulsdon, UK: Jane's, ISBN 978-0-7106-1208-3.

- Nunez Padin, Jorge Felix (November 1993). "Les Super Etendards argentins" [Argentinian Super Etendards]. Avions: Toute l'aéronautique et son histoire (in French) (9): 2–7. ISSN 1243-8650.

- Polmar, Norman (2006), Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and Its Influence on World Events, vol. I: 1909–1945, Potomac, ISBN 978-1-574886-63-4.

- Ripley, Tim. "Directory: Military Aircraft". Flight International, 25–31 May 2004. Sutton, UK: Reed Business Press, pp. 38–73.

- Taylor, John W.R. (ed). Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1982–83. London: Jane's Yearbooks, 1982. ISBN 0-7106-0748-2.

Further reading

- Lert, Frederic (2011). DASSAULT SUPER ETENDARD: De l'Etendard IV au Standard Modernise. Les Materiels de L'Armee De L'Air et de L'Aeronavale (in French). Vol. 10. Histoire and Collections. ISBN 978-2-35250-175-6. Archived from the original on 2014-08-26. Retrieved 2014-08-23.

- Núñez Padin, Jorge Felix (2012). Núñez Padin, Jorge Felix (ed.). Dassault Super Etendard. Serie Aeronaval (in Spanish). Vol. 30. Bahía Blanca, Argentina: Fuerzas Aeronavales. ISBN 978-987-1682-12-6. Archived from the original on 2014-05-09. Retrieved 2014-08-23.