David IV of Georgia

David IV, also known as David IV the Builder[1] (Georgian: დავით IV აღმაშენებელი, Davit IV Aghmashenebeli) (1073–1125), of the Bagrationi dynasty, was the 5th king of United Georgia from 1089 until his death in 1125.[2]

| David IV the Builder დავით IV აღმაშენებელი | |

|---|---|

| King of Kings of Georgia | |

.jpg.webp) A fresco of King David IV from Gelati Monastery | |

| King of Georgia | |

| Reign | 1089–1125 |

| Predecessor | George II |

| Successor | Demetrius I |

| Born | 1073 Kutaisi |

| Died | 1125 (aged 51–52) Tbilisi |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Rusudan of Armenia Gurandukht of the Kipchaks |

| Issue | Demetrius I Vakhtang George Tamar Kata |

| Dynasty | Bagrationi |

| Father | George II of Georgia |

| Mother | Elene |

| Religion | Georgian Orthodox Church |

| Khelrtva | |

Popularly considered to be the greatest and most successful Georgian ruler in history and an original architect of the Georgian Golden Age, he succeeded in driving the Seljuk Turks out of the country, winning the Battle of Didgori in 1121. His reforms of the army and administration enabled him to reunite the country and bring most of the lands of the Caucasus under Georgia's control. A friend of the Church and a notable promoter of Christian culture, he was canonized by the Georgian Orthodox Church.

Sobriquet and regnal ordinal

The epithet aghmashenebeli (აღმაშენებელი), which is translated as "the Builder" (in the sense of "built completely"), "the Rebuilder",[3] or "the Restorer",[4][5] first appears as the sobriquet of David in the charter issued in the name of "King of Kings Bagrat" in 1452 and becomes firmly affixed to him in the works of the 17th- and 18th-century historians such as Parsadan Gorgijanidze, Beri Egnatashvili and Prince Vakhushti.[6] Epigraphic data also provide evidence for the early use of David's other epithet, "the Great" (დიდი, didi).[7]

Retrospectively, David the Builder has been variously referred to as David II, III, and IV, reflecting substantial variation in the ordinals assigned to the Georgian Bagratids, especially in the early period of their history, owing to the fact that the numbering of successive rulers moves between the many branches of the family.[8][9] Scholars in Georgia favor David IV,[8] his namesake predecessors being: David I Curopalates (died 881), David II Magistros (died 937), and David III Curopalates (died 1001), all members of the principal line of the Bagratid dynasty.[10]

Family background and early life

The year of David's birth can be calculated from the date of his accession to the throne recorded in the Life of King of Kings David (ცხორებაჲ მეფეთ-მეფისა დავითისი), written c. 1123–1126,[11][12] as k'oronikon (Paschal cycle) 309, that is, 1089, when he was 16 years old. Thus, he would have been born in k'oronikon 293 or 294, that is, c. 1073. According to the same source, he died in k'oronikon 345, when he would have been in his 52nd or 53rd year. Professor Cyril Toumanoff gives 1070 and 24 January 1125 as the dates for David.[13] The earliest known document that makes mention of David is the royal charter of his father, George II of Georgia (r. 1072–1089), granted to the Mghvime monastery and dated to 1073.

According to the Life of King of Kings David, David was the only son of George II. The contemporaneous Armenian chronicler Matthew of Edessa mentions David's brother Totorme,[14] who, according to the modern historian Robert W. Thomson, was his sister.[13] The name of David's mother, Elene, is recorded in a margin note in the Gospel of Matthew from the Tskarostavi monastery; she is otherwise unknown. David bore the name of the biblical king-prophet, from whom the Georgian Bagratids claimed their descent and whose 78th descendant David was proclaimed to be.[13]

David's father, George II, was confronted by a major threat to the kingdom of Georgia. The country was invaded by the Seljuq Turks, which were part of the same wave which had overrun Anatolia, defeating the Byzantine Empire and taking captive the emperor Romanos IV Diogenes at the battle of Manzikert in 1071.[15] In what the medieval Georgian chronicle refers to as didi turkoba, "the Great Turkish Invasion", several provinces of Georgia became depopulated and George was forced to sue for peace, becoming a tributary of the sultan Malik-Shah I in 1083 when David was 10. The great noble houses of Georgia, capitalizing on the vacillating character of the king, sought to assert more autonomy for themselves; Tbilisi, the ancient capital of Kartli, remained in the hands of its Muslim rulers, and a local dynasty, for a time suppressed by George's energetic father Bagrat IV, maintained its precarious independence in the eastern region of Kakheti under the Seljuq suzerainty.[16]

Accession to the throne

Watching his kingdom slip into chaos, George II ceded the crown to his 16-year-old son David in 1089. Although the historical tradition founded by Prince Vakhushti in the 18th century and followed by Marie-Félicité Brosset in the 19th states that David succeeded George upon his death, a number of surviving documents suggest that George died around 1112, and that although he retained the royal title until his death,[17][18] he played no significant political role, real power having passed on to David.[18] Moreover, David himself had been a co-ruler with his father sometime before his becoming a king-regnant in 1089; a document of 1085 mentions David as "king and sebastos", the latter being a Byzantine title,[17] frequently held, like other imperial dignities, by the members of the Georgian royal family. David's formal cooption into government may have occurred even earlier, in 1083, when George II left Georgia for the negotiations at the court of the Seljuq sultan Malik-Shah I.

Revival of the Georgian State

.jpg.webp)

Despite his young age, he was actively involved in Georgia's political life. Backed by his tutor and an influential churchman George of Chqondidi, David IV pursued a purposeful policy, taking no unconsidered step. He was determined to bring order to the land, bridle the unsubmissive secular and ecclesiastic feudal lords, centralize the state administration, form a new type of army that would stand up better to the Seljuk Turkish military organization, and then go over to a methodical offensive with the aim of expelling the Seljuks first from Georgia and then from the whole Caucasus. Between 1089 and 1100, King David organized small detachments of his loyal troops to restore order and destroy isolated enemy troops. He began the resettlement of devastated regions and helped to revive major cities.[19] Encouraged by his success, but more importantly the beginning of the Crusades in Palestine, he ceased payment of the annual contribution to the Seljuks and put an end to their seasonal migration to Georgia. In 1101, King David captured the fortress of Zedazeni, a strategic point in his struggle for Kakheti and Hereti, and within the next three years he liberated most of eastern Georgia.

In 1093, he arrested the powerful feudal lord Liparit Baghvashi, a long-time enemy of the Georgian crown, and expelled him from Georgia (1094). After the death of Liparit's son Rati, David abolished their duchy of Kldekari in 1103.

He slowly pushed the Seljuk Turks out of the country, recovering more and more land from them as they were now forced to focus not only on the Georgians but the newly begun Crusades in the eastern Mediterranean.[20] By 1099 David IV's power was considerable enough that he was able to refuse paying tribute to the Turks. By that time, he also rejected a Byzantine title of panhypersebastos [21] thus indicating that Georgia would deal with the Byzantine Empire only on a parity basis.

In 1103 a major ecclesiastical congress known as the Ruis-Urbnisi Synod was held at the monasteries of Ruisi and Urbnisi. David succeeded in removing oppositionist bishops, and combined two offices: courtier's (Mtsignobartukhutsesi, i.e. Chief Secretary) and clerical (Bishop of Tchqondidi) into a single institution of Tchqondidel-Mtzignobartukhutsesi corresponding roughly to the post of prime minister.

Next year, David's supporters in the eastern Georgian province of Kakheti captured the local king Aghsartan II (1102–1104), a loyal tributary of the Seljuk Sultan, and reunited the area with the rest of Georgia.

Military campaigns

Following the annexation of Kingdom of Kakheti, in 1105, David routed a Seljuk punitive force at the Battle of Ertsukhi, leading to momentum that helped him to secure the key fortresses of Samshvilde, Rustavi, Gishi, and Lori between 1110 and 1118.

Problems began to crop up for David now. His population, having been at war for the better part of twenty years, needed to be allowed to become productive again. Also, his nobles were still making problems for him, along with the city of Tbilisi which still could not be liberated from Seljuk grasp. Again David was forced to solve these problems before he could continue the reclamation of his nation and people. For this purpose, David IV radically reformed his military. He resettled a Kipchak tribe of 40,000 families from the Northern Caucasus in Georgia in 1118–1120. Every Georgian and Kipchak family was obliged to provide one soldier with a horse and weapons. Kipchaks were settled in different regions of Georgia. Some were settled in Inner Kartli province, others were given lands along the border. They were Christianized and quickly assimilated into Georgian society.

In 1120, David IV moved to western Georgia and, when the Turks began pillaging Georgian lands, he suddenly attacked them in Botori. Only an insignificant Seljuk force escaped. King David then entered the neighbouring Shirvan and took the town of Qabala. During that time Shirvanshahs were in position of power shifting between emerging Georgia and Seljuqid states.

In the winter of 1120–1121, the Georgian troops successfully attacked the Seljuk settlements on the eastern and southwestern approaches to the Transcaucasus.[22]

Muslim powers became increasingly concerned about the rapid rise of a Christian state in southern Caucasia. In 1121, Sultan Mahmud b. Muhammad (1118–1131) declared a holy war on Georgia and rallied a large coalition of Muslim states led by the Artuqid Ilghazi and Toğrul b. Muhammad. The size of the Muslim army is still a matter of debate with numbers ranging from a fantastic 600,000 men (Walter the Chancellor’s Bella Antiochena, Matthew of Edessa) to 400,000 (Smbat Sparapet’s Chronicle) to modern Georgian estimates of 250,000–400,000 men. All sources agree that the Muslim powers gathered an army that was much larger than the Georgian force of 56,000 men. However, on 12 August 1121, King David routed the enemy army on the field of Didgori, achieving what is often considered the greatest military success in Georgian history. The victory at Didgori signaled the emergence of Georgia as a great military power and shifted the regional balance in favor of Georgian cultural and political supremacy.

Following his success, David captured Tbilisi,[23] the last Muslim enclave remaining from the Arab occupation, in 1122 and moved the Georgian capital there. A well-educated man, he preached tolerance and acceptance of other religions, abrogated taxes and services for the Muslims and Jews, and protected the Sufis and Muslim scholars. In 1123, David’s army liberated Dmanisi, the last Seljuk stronghold in southern Georgia. In 1124, David finally conquered Shirvan and took the Armenian city of Ani from the Muslim emirs,[23] thus expanding the borders of his kingdom to the Araxes basin. Armenians met him as a liberator providing some auxiliary force for his army. It was then that the important component of "Sword of the Messiah" appeared in the title of David the Builder. It is engraved on a copper coin of David's day:

King of Kings, David, son of George, Sword of the Messiah.

Humane treatment of the Muslim population, as well as the representatives of other religions and cultures, set a standard for tolerance in his multiethnic kingdom. It was a hallmark not only for his enlightened reign, but for all of Georgian history and culture.

After Georgia's decisive victory at the battle of Didgori, Shirvanshah Manuchir, who was under the influence of his wife, Georgian princess Tamar, maintained a pro-Georgian orientation and rejected paying tribute to the Seljuqids. Deprived of the tribute, 40,000 dinars, the Seljuqid Sultan Mahmud directed to Shirvan at the beginning of 1123, captured Shamakhi and took Shah as hostage contrary to Manuchehr's betrayal. In the response to this, in June 1123 David IV attacked and defeated Sultan again and finally conquered Shirvan by capturing the cities and fortresses of Shamakhi, Bughurd, Gulustan, Shabran.

David the Builder died on 24 January 1125, and upon his death, as he had specified, was buried under the stone inside the main gatehouse of the Gelati Monastery so that anyone coming to his beloved Gelati Academy stepped on his tomb first. He was survived by three children, his eldest son Demetrius, who succeeded him and continued his father's victorious reign; and two daughters, Tamar, who was married to the Shirvan Shah Manuchihr III, and Kata (Katai), married to Isaac Comnenus, the son of the Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Comnenus. Beside his political and military skills, King David earned fame as a writer, composing Galobani sinanulisani (Hymns of Repentance, c. 1120), a powerful work of emotional free-verse psalms, which reveal the king's humility and religious zeal.

Cultural life

King David the Builder gave close attention to the education of his people. The king selected children who were sent to the Byzantine Empire "so that they be taught languages and bring home translations made by them there". Many of them later became well-known scholars.

At the time of David the Builder there were quite a few schools and academies in Georgia, among which Gelati occupies a special place. King David's historian calls Gelati Academy

a second Jerusalem of all the East for learning of all that is of value, for the teaching of knowledge – a second Athens, far exceeding the first in divine law, a canon for all ecclesiastical splendors.

Besides Gelati there also were other cultural-enlightenment and scholarly centers in Georgia at that time, e.g. the academy of Ikalto.

David himself composed, c. 1120, "Hymns of Repentance" (გალობანი სინანულისანი, galobani sinanulisani), a sequence of eight free-verse psalms, with each hymn having its own intricate and subtle stanza form. For all their Christianity, cult of the Mother of God, and the king's emotional repentance of his sins, David sees himself to be similar to the Biblical David, with a similar relationship to God and to his people. His hymns also share the idealistic zeal of the contemporaneous European crusaders to whom David was a natural ally in his struggle against the Seljuks.[24]

Family

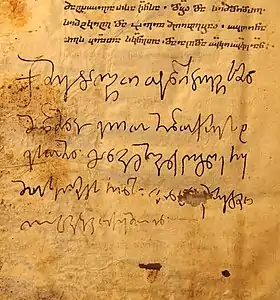

"მე დავით უნარჩევესმან მონამან ჴელითა მონითა ქრისტესთა მან გავგზავნე წიგნი ესე მთას წმიდას სინას ვინც მოიხმარებდეთ ლოცვა ყავთ ჩემთვინ"

"I David the servant of Jesus sent this book to Holy Mount Sinai and who uses it pray for me"

Document from Saint Catherine's Monastery, 12th century

Marriages

Issue

- Demetrius I

- Prince Vakhtang (1112–1138)

- Prince George (1114–1129)

- Princess Rusudan, who was married to Prince of Alania.

- Zurab, son of David IV of Georgia

- Princess Tamar, who married Shirvanshah Manuchehr III (died c. 1154), and became a nun in widowhood.

- Princess Kata, who has been theorized to be the same person as Irene who married the Byzantine prince Isaakios Comnenus.

Burial

Ⴕ ႤႱႤႠႰႱႢႠႬ

ႱႠႱႭႤႬႤ

ႡႤႪႨႹ[ႫႨ]

[ႭႩႨႭႩႤ]

[ႤႱႤ]ႫႧႬႠ

ႥႱႠႵႠႣႠ

ႥႤႫႩჃႣႰႭ

ႫႤ

A tombstone at the entrance of Gelati monastery, bearing a Georgian inscription in the asomtavruli script, has traditionally been considered to be that of David IV. Although there are no clear and reliable indications that David was indeed buried in Gelati and that the present epitaph is his, this popular belief had already been established by the mid-19th century as evidenced by the French scholar Marie-Félicité Brosset who published his study of the Georgian history between 1848 and 1858. The epitaph, modeled on the Psalm 131 (132), 14, reads: "Christ! This is my resting place for eternity. It pleases me; here I shall dwell."[25]

Legacy

Also known as David the Builder, he occupies a special place among the kings of the Georgian “Golden Age” in the period of the defense against the Seljuqs.[26] The "Order of David the Builder" is given to regular citizens, military and clerical personnel for outstanding contributions to the country, for fighting for the independence of Georgia and its revival, and for significantly contributing to social consolidation and the development of democracy.[27]

After being elected President of Georgia, Georgia's former leader Mikheil Saakashvili took an oath at David the Builder's tomb at Gelati Monastery on the day of his inauguration on 25 January 2004.

The airport at Kutaisi is known as David the Builder Kutaisi International Airport. The National Defense Academy is named after him.

See also

![]() Media related to David IV of Georgia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to David IV of Georgia at Wikimedia Commons

References

- Notes

- Britannica online

- Georgia in the Developed Feudal Period (XI–the first quarter of the XIII c.) www.parliament.ge/ Retrieved 13 August 2006.

- Rapp 2003, p. 161

- Massingberd 1980, p. 60

- Vasiliev 1936, p. 4

- Mariam Lortkipanidze, Roin Metreveli, Kings of Georgia, Tbilisi, 2007, pp. 122–130 ISBN 99928-58-36-2

- Otkhmezuri 2012, p. 38

- Rapp 2007, p. 189

- Eastmond 1998, p. 262

- Metreveli 1990, pp. 10–11

- Toumanoff 1943, p. 174

- Rapp 2007, p. 210

- Thomson 1996, p. 315

- Dostourian 1993, p. 231

- Rapp 2000, p. 572

- Toumanoff 1966, p. 624

- Toumanoff 1943, pp. 174–175, n. 63

- Eastmond 1998, p. 46

- "Blessed David IV the King of Georgia", Orthodox Church in America

- Fighting against the Seljuks, Georgia and the Crusaders developed fairly friendly relations. A 13th-century anonymous Georgian author (conventionally known as the First Chronicler of Queen Tamar) as well as Abul-Faraj gives a version, though unproven otherwise, about the participation of a Georgian auxiliary force in the Siege of Jerusalem (1099). Some 300 Crusaders (known to the Georgians as Franks) are also known to take part in the famous Battle of Didgori (1121). King Baldwin II of Jerusalem is said by the historian Ioane Bagrationi, who refers to unknown medieval sources, to have visited incognito David IV’s court

- Since the Bagrationi dynasty established the Tao-Klarjeti principality under the Byzantine protectorate in 813, representatives of the dynasty had been granted various Byzantine titles such as kouropalates, magistros, sebastos, etc. David was the last Georgian monarch to wear a Byzantine title.

- Gocha Japaridze, Georgia and the Islamic world of the Near East in the first third of the XII–XIII centuries, Tbilisi, 1995, pp. 38–39

- Pubblici 2022, p. 20.

- Donald Rayfield, "Davit II", in: Robert B. Pynsent, S. I. Kanikova (1993), Reader's Encyclopedia of Eastern European Literature, p. 82. HarperCollins, ISBN 0-06-270007-3.

- Jost Gippert / Manana Tandashvili (2002), The Epitaph of David the Builder. Gelati Academy of Sciences Project: Old Georgian texts from the Gelati school (TITUS project). Accessed 19 June 2011.

- Hannick, Christian, “David IV of Georgia”, in: Religion Past and Present. First print edition: ISBN 978-9004146662, 2006

- "State Awards Issued by Georgian Presidents in 2003–2015"

- General

- Dostourian, Ara Edmond, ed. (1993). Armenia and the Crusades, Tenth to Twelfth Centuries: The Chronicle of Matthew of Edessa. Lanham, Md.: University Press of America. ISBN 0819189537.

- Eastmond, Antony (1998). Royal Imagery in Medieval Georgia. University Park: Pennsylvania State Press. ISBN 0271016280.

- Lordkipanidze, Mariam (1987). Georgia in the 11th–12th centuries. Tbilisi. pp. 80–118.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Metreveli, Roin (1990). Davitʻ Aġmašenebeli. Tʻbilisi: Ganatʻleba. ISBN 5-505-01428-3.

- Grand Larousse encyclopédique (in French). Vol. 5. Paris. 1962. pp. 452–453.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Enciclopedia Italiana (in Italian). Rome. 1950. pp. 641–643.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Massingberd, Hugh (1980). Burke's Royal Families of the World: Volume II Africa & the Middle East. pp. 56–67. ISBN 0-85011-029-7.

- Rapp, Stephen H. Jr. (2000). "Sumbat Davitʿis-dze and the Vocabulary of Political Authority in the Era of Georgian Unification". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 120 (4): 570–576. doi:10.2307/606617. JSTOR 606617.

- Rapp, Stephen H. (2003). Studies In Medieval Georgian Historiography: Early Texts And Eurasian Contexts. Leuven: Peeters. ISBN 9042913185.

- Rapp, Stephen H., Jr (2007). The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1444333619. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Otkhmezuri, Giorgi (2012), Epigraphic Monuments of the Epoch of David the Builder ("Agmashenebeli")

- Synod of Ruis-Urbnisi (1103), ed. E. Gabidzashvili, Tbilisi, 1978, on Georgian language.

- Khuroshvili, Giorgi (2018), Conceptions of Political Thought in Medieval Georgia: David IV “the Builder”, Arson of Ikalto. In: Veritas et subtilitas. Truth and Subtlety in the History of Philosophy. John Benjamins Publishing Company. Amsterdam/Philadelphia. pp. 149–156. ISBN 978-9027200686

- Kiziria, Dodona (1994). "The Prayers of Remorse of King David IV the Builder". Le Muséon. 107 (3): 335–347. doi:10.2143/MUS.107.3.2006012.

- Pubblici, Lorenzo (2022). Mongol Caucasia: Invasions, Conquest, and Government of a Frontier Region in Thirteenth-Century Eurasia (1204-1295). Brill.

- Thomson, Robert W. (1996). Rewriting Caucasian history: the medieval Armenian adaptation of the Georgian chronicles; the original Georgian texts and the Armenian adaptation. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198263732.

- Toumanoff, Cyril (1943). "Medieval Georgian Historical Literature (VIIth–XVth Centuries)". Traditio. I.

- Toumanoff, Cyril (1966). "Armenia and Georgia". The Cambridge Medieval History (Volume 4). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 593–637.

- Vasiliev, Alexander (January 1936). "The Foundation of the Empire of Trebizond (1204–1222)". Speculum. The University of Chicago Press. 11 (1): 3–37. doi:10.2307/2846872. JSTOR 2846872. S2CID 162791512.

Further reading

- Toria, Malkhaz; Javakhia, Bejan (2021). "Representing fateful events and imagining territorial integrity in Georgia: cultural memory of David the Builder and the Battle of Didgori". Caucasus Survey. 9 (3): 270–285. doi:10.1080/23761199.2021.1970914. S2CID 238993015.