Denazification

Denazification (German: Entnazifizierung) was an Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of the Nazi ideology following the Second World War. It was carried out by removing those who had been Nazi Party or SS members from positions of power and influence, by disbanding or rendering impotent the organizations associated with Nazism, and by trying prominent Nazis for war crimes in the Nuremberg trials of 1946. The program of denazification was launched after the end of the war and was solidified by the Potsdam Agreement in August 1945. The term denazification was first coined as a legal term in 1943 by the U.S. Pentagon, intended to be applied in a narrow sense with reference to the post-war German legal system. However, it later took on a broader meaning.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Nazism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Fascism |

|---|

|

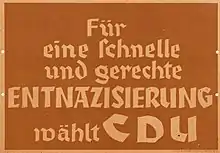

In late 1945 and early 1946, the emergence of the Cold War and the economic importance of Germany caused the United States in particular to lose interest in the program, somewhat mirroring the Reverse Course in American-occupied Japan. The British handed over denazification panels to the Germans in January 1946, while the Americans did likewise in March 1946. The French ran the mildest denazification effort. Denazification was carried out in an increasingly lenient and lukewarm way until being officially abolished in 1951. Additionally, the program was hugely unpopular in West Germany, where many Nazis maintained positions of power. Denazification was opposed by the new West German government of Konrad Adenauer,[2] who declared that ending the process was necessary for West German rearmament. On the other hand, denazification in East Germany was considered a critical element of the transformation into a socialist society, and the country was stricter in opposing Nazism than its counterpart. However, not all former Nazis faced judgment. Doing special tasks for the occupation governments could protect Nazi members from prosecution, enabling them to continue working and in some cases reach prominence as was the case of Wernher von Braun, a former Nazi Party member who among other German scientists was recruited by the United States through Operation Paperclip and later led the American lunar program,[3][4][5][6] as did special connections with the occupiers.[7]

Overview

About 8 million Germans, or 10% of the population, had been members of the Nazi Party. Nazi-related organizations also had huge memberships, such as the German Labor Front (25 million), the National Socialist People's Welfare organization (17 million), the League of German Women, and others.[8] It was through the Party and these organizations that the Nazi state was run, involving as many as 45 million Germans in total.[9] In addition, Nazism found significant support among industrialists, who produced weapons or used slave labor, and large landowners, especially the Junkers in Prussia. Denazification after the surrender of Germany was thus an enormous undertaking, fraught with many difficulties.

The first difficulty was the enormous number of Germans who might have to be first investigated, then penalized if found to have supported the Nazi state to an unacceptable degree. In the early months of denazification there was a great desire to be utterly thorough, to investigate every suspect and hold every supporter of Nazism accountable; however, it was decided that the numbers simply made this goal impractical. The Morgenthau Plan had recommended that the Allies create a post-war Germany with all its industrial capacity destroyed, reduced to a level of subsistence farming; however, that plan was soon abandoned as unrealistic and, because of its excessive punitive measures, liable to give rise to German anger and aggression.[10] As time went on, another consideration that moderated the denazification effort in the West was the concern to keep enough good will of the German population to prevent the growth of communism.[11]

The denazification process was often completely disregarded by both the Soviets and the Western powers for German rocket scientists and other technical experts, who were taken out of Germany to work on projects in the victors' own countries or simply seized in order to prevent the other side from taking them. The US took 785 scientists and engineers from Germany to the United States, some of whom formed the backbone of the US space program (see Operation Paperclip).[12]

In the case of the top-ranking Nazis, such as Göring, Hess, von Ribbentrop, Streicher, and Speer, the initial proposal by the British was to simply arrest them and shoot them,[13] but that course of action was replaced by putting them on trial for war crimes at the Nuremberg Trials in order to publicize their crimes while demonstrating that the trials and the sentences were just, especially to the German people. However, the legal foundations of the trials were questioned, and many Germans were not convinced that the trials were anything more than "victors' justice".[14]

Many refugees from Nazism were Germans and Austrians, and some had fought for Britain in the Second World War. Some were transferred into the Intelligence Corps and sent back to Germany and Austria in British uniform. However, German-speakers were small in number in the British zone, which was hampered by the language deficit. Due to its large German-American population, the US authorities were able to bring a larger number of German-speakers to the task of working in the Allied Military Government, although many were poorly trained.[15][16] They were assigned to all aspects of military administration, the interrogation of POWs, collecting evidence for the War Crimes Investigation Unit and the search for war criminals.

Application

American zone

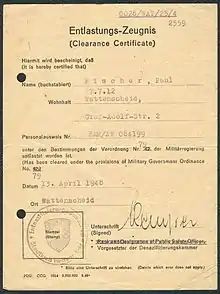

The Joint Chiefs of Staff Directive 1067 directed US Army General Dwight D. Eisenhower's policy of denazification. A report of the Institute on Re-education of the Axis Countries in June 1945 recommended: "Only an inflexible long-term occupation authority will be able to lead the Germans to a fundamental revision of their recent political philosophy." The United States military pursued denazification in a zealous and bureaucratic fashion, especially during the first months of the occupation.[17] It had been agreed among the Allies that denazification would begin by requiring Germans to fill in a questionnaire (German: Fragebogen) about their activities and memberships during Nazi rule. Five categories were established: Major Offenders, Offenders, Lesser Offenders, Followers, and Exonerated Persons. The Americans, unlike the British, French, and Soviets, interpreted this to apply to every German over the age of eighteen in their zone.[18] Eisenhower initially estimated that the denazification process would take 50 years.[19]

When the nearly complete list of Nazi Party memberships was turned over to the Allies (by a German anti-Nazi who had rescued it from destruction in April 1945 as American troops advanced on Munich), it became possible to verify claims about participation or non-participation in the Party.[20] The 1.5 million Germans who had joined before Hitler came to power were deemed to be hard-core Nazis.[9]

Progress was slowed by the overwhelming numbers of Germans to be processed, but also by difficulties such as incompatible power systems and power outages, as with the Hollerith IBM data machine that held the American vetting list in Paris. As many as 40,000 forms could arrive in a single day to await processing. By December 1945, even though a full 500,000 forms had been processed, there remained a backlog of 4,000,000 forms from POWs and a potential case load of 7,000,000.[21] The Fragebögen were, of course, filled out in German. The number of Americans working on denazification was inadequate to handle the workload, partly as a result of the demand in the US by families to have soldiers returned home.[22] Replacements were mostly unskilled and poorly trained.[23] In addition, there was too much work to be done to complete the process of denazification by 1947, the year American troops were expected to be completely withdrawn from Europe.

Pressure also came from the need to find Germans to run their own country. In January 1946 a directive came from the Control Council entitled "Removal from Office and from Positions of Responsibility of Nazis and Persons Hostile to Allied Purposes". One of the punishments for Nazi involvement was to be barred from public office and/or restricted to manual labor or "simple work". At the end of 1945, 3.5 million former Nazis awaited classification, many of them barred from work in the meantime.[24] By the end of the winter of 1945–1946, 42% of public officials had been dismissed.[25] Malnutrition was widespread, and the economy needed leaders and workers to help clear away debris, rebuild infrastructure, and get foreign exchange to buy food and other essential resources.[9]

Another concern leading to the Americans relinquishing responsibility for denazification and handing it over to the Germans arose from the fact that many of the American denazifiers were German Jews, former refugees returning to administer justice against the tormentors and killers of their relatives. It was felt, both among Germans and top American officials, that their objectivity might be contaminated by a desire for revenge.[26]

As a result of these various pressures, and following a January 15, 1946, report of the Military Government decrying the efficiency of denazification, saying, "The present procedure fails in practice to reach a substantial number of persons who supported or assisted the Nazis", it was decided to involve Germans in the process. In March 1946 the Law for Liberation from National Socialism and Militarism (German: Befreiungsgesetz) came into effect, turning over responsibility for denazification to the Germans.[27] Each zone had a Minister of Denazification. On April 1, 1946, a special law established 545 civilian tribunals under German administration (German: Spruchkammern), with a staff of 22,000 of mostly lay judges, enough, perhaps, to start to work but too many for all the staff themselves to be thoroughly investigated and cleared.[28] They had a case load of 900,000. Several new regulations came into effect in the setting up of the German-run tribunals, including the idea that the aim of denazification was now rehabilitation rather than merely punishment, and that someone whose guilt might meet the formal criteria could also have their specific actions taken into consideration for mitigation.[29] Efficiency thus improved, while rigor declined.

Many people had to fill in a new background form, called a Meldebogen (replacing the widely disliked Fragebogen), and were given over to justice under a Spruchkammer,[18] which assigned them to one of five categories:[27][30][31]

- V. Persons Exonerated (German: Entlastete). No sanctions.

- IV. Followers (German: Mitläufer). Possible restrictions on travel, employment, political rights, plus fines.

- III. Lesser Offenders (German: Minderbelastete). Placed on probation for 2–3 years with a list of restrictions. No internment.

- II. Offenders: Activists, Militants, and Profiteers, or Incriminated Persons (German: Belastete). Subject to immediate arrest and imprisonment up to ten years performing reparation or reconstruction work plus a list of other restrictions.

- I. Major Offenders (German: Hauptschuldige). Subject to immediate arrest, death, imprisonment with or without hard labor, plus a list of lesser sanctions.

Again because the caseload was impossibly large, the German tribunals began to look for ways to speed up the process. Unless their crimes were serious, members of the Nazi Party born after 1919 were exempted on the grounds that they had been brainwashed. Disabled veterans were also exempted. To avoid the necessity of a slow trial in open court, which was required for those belonging to the most serious categories, more than 90% of cases were judged not to belong to the serious categories and therefore were dealt with more quickly.[32] More "efficiencies" followed. The tribunals accepted statements from other people regarding the accused's involvement in Nazism. These statements earned the nickname of Persilscheine, after advertisements for the laundry and whitening detergent Persil.[33] There was corruption in the system, with Nazis buying and selling denazification certificates on the black market. Nazis who were found guilty were often punished with fines assessed in Reichsmarks, which had become nearly worthless.[34] In Bavaria, the Denazification Minister, Anton Pfeiffer, bridled under the "victor's justice", and presided over a system that reinstated 75% of officials the Americans had dismissed and reclassified 60% of senior Nazis.[35] The denazification process lost a great deal of credibility, and there was often local hostility against Germans who helped administer the tribunals.[36]

By early 1947, the Allies held 90,000 Nazis in detention; another 1,900,000 were forbidden to work as anything but manual laborers.[37] From 1945 to 1950, the Allied powers detained over 400,000 Germans in internment camps in the name of denazification.[38]

By 1948, the Cold War was clearly in progress and the US began to worry more about a threat from the Eastern Bloc rather than the latent Nazism within occupied Germany.[39]

The delicate task of distinguishing those truly complicit in or responsible for Nazi activities from mere "followers" made the work of the courts yet more difficult. US President Harry S. Truman alluded to this problem: "though all Germans might not be guilty for the war, it would be too difficult to try to single out for better treatment those who had nothing to do with the Nazi regime and its crimes."[40] Denazification was from then on supervised by special German ministers, like the Social Democrat Gottlob Kamm in Baden-Württemberg, with the support of the US occupation forces.

Contemporary American critics of denazification denounced it as a "counterproductive witch hunt" and a failure; in 1951 the provisional West German government granted amnesties to lesser offenders and ended the program.[41]

Censorship

While judicial efforts were handed over to German authorities, the US Army continued its efforts to denazify Germany through control of German media. The Information Control Division of the US Army had by July 1946 taken control of 37 German newspapers, six radio stations, 314 theaters, 642 cinemas, 101 magazines, 237 book publishers, and 7,384 book dealers and printers.[42] Its main mission was democratization but part of the agenda was also the prohibition of any criticism of the Allied occupation forces.[43] In addition, on May 13, 1946, the Allied Control Council issued a directive for the confiscation of all media that could contribute to Nazism or militarism. As a consequence a list was drawn up of over 30,000 book titles, ranging from school textbooks to poetry, which were then banned. All copies of books on the list were confiscated and destroyed; the possession of a book on the list was made a punishable offense. All the millions of copies of these books were to be confiscated and destroyed. The representative of the Military Directorate admitted that the order was in principle no different from the Nazi book burnings.[44]

The censorship in the US zone was regulated by the occupation directive JCS 1067 (valid until July 1947) and in the May 1946 order valid for all zones (rescinded in 1950), Allied Control Authority Order No. 4, "No. 4 – Confiscation of Literature and Material of a Nazi and Militarist Nature". All confiscated literature was reduced to pulp instead of burning.[Notes 1] It was also directed by Directive No. 30, "Liquidation of German Military and Nazi Memorials and Museums". An exception was made for tombstones "erected at the places where members of regular formations died on the field of battle".

Artworks were under the same censorship as other media: "all collections of works of art related or dedicated to the perpetuation of German militarism or Nazism will be closed permanently and taken into custody." The directives were very broadly interpreted, leading to the destruction of thousands of paintings and thousands more were shipped to deposits in the US. Those confiscated paintings still surviving in US custody include for example a painting "depicting a couple of middle aged women talking in a sunlit street in a small town".[45] Artists were also restricted in which new art they were allowed to create; "OMGUS was setting explicit political limits on art and representation".[45]

The publication Der Ruf (The Call) was a popular literary magazine first published in 1945 by Alfred Andersch and edited by Hans Werner Richter. Der Ruf, also called Independent Pages of the New Generation, claimed to have the aim of educating the German people about democracy. In 1947 its publication was blocked by the American forces for being overly critical of occupational government.[46] Richter attempted to print many of the controversial pieces in a volume entitled Der Skorpion (The Scorpion). The occupational government blocked publication of Der Skorpion before it began, saying that the volume was too "nihilistic".[47]

Publication of Der Ruf resumed in 1948 under a new publisher, but Der Skorpion was blocked and not widely distributed. Unable to publish his works, Richter founded Group 47.

The Allied costs for occupation were charged to the German people. A newspaper which revealed the charges (including, among other things, thirty thousand bras) was banned by the occupation authorities for revealing this information.[48]

Soviet zone

From the beginning, denazification in the Soviet zone was considered a critical element of the transformation into a socialist society and was quickly and effectively put into practice.[5] Members of the Nazi Party and its organizations were arrested and interned.[49] The NKVD was directly in charge of this process, and oversaw the camps. In 1948, the camps were placed under the same administration as the gulag in the Soviet government. According to official records, 122,600 people were interned. 34,700 of those interned in this process were considered to be Soviet citizens, with the rest being German.[50] This process happened at the same time as the expropriation of large landowners and Junkers, who were also often former Nazi supporters.[51]

Because part of the intended goal of denazification in the Soviet zone was also the removal of anti-socialist sentiment, the committees in charge of the process were politically skewed. A typical panel would have one member from the Christian Democratic Union, one from the Liberal Democratic Party of Germany, three from the Socialist Unity Party of Germany, and three from political mass organizations (who were typically also supportive of the Socialist Unity Party).[52]

Former Nazi officials quickly realized that they would face fewer obstacles and investigations in the zones controlled by the Western Allies. Many of them saw a chance to defect to the West on the pretext of anti-communism.[53] Conditions in the internment camps were terrible, and between 42,000 and 80,000 prisoners died. When the camps were closed in 1950, prisoners were handed over to the East German government.[54]

Because many of the functionaries of the Soviet occupation zone were themselves formerly prosecuted by the Nazi regime, mere former membership in the NSDAP was judged as a crime.[49]

Even before denazification was officially abandoned in West Germany, East German propaganda frequently portrayed itself as the only true anti-fascist state, and argued that the West German state was simply a continuation of the Nazi regime, employing the same officials that had administered the government during the Nazi dictatorship. From the 1950s, reasoning for these accusations focused on the fact that many former functionaries of Nazi regime were employed in positions in the West German government. However, East German propaganda also attempted to denounce as Nazis even politicians such as Kurt Schumacher, who had been imprisoned by the Nazi regime himself.[55] Such allegations appeared frequently in the official Socialist Unity Party of Germany newspaper, the Neues Deutschland. The East German uprising of 1953 in Berlin was officially blamed on Nazi agents provocateurs from West Berlin, who the Neues Deutschland alleged were then working in collaboration with the Western government with the ultimate aim of restoring Nazi rule throughout Germany. The Berlin Wall was officially called the Anti-Fascist Security Wall (German: Antifaschistischer Schutzwall) by the East German government.[56] As part of the propagandistic campaign against West Germany, Theodor Oberländer and Hans Globke, both former Nazi leaders involved in genocide, were among the first federal politicians to be denounced in the GDR. Both were sentenced to life imprisonment in absentia by the GDR in April 1960, and in July 1963.[57] The president of West Germany Heinrich Lübke, in particular, was denounced during the official commemorations of the liberation of the concentration camps of Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen held at the GDR's National Memorials.[58]

Not all former Nazis faced judgment. Doing special tasks for the Soviet government could protect Nazi members from prosecution, enabling them to continue working.[4][6] Having special connections with the occupiers in order to have someone vouch for them could also shield a person from the denazification laws.[7] In particular, the districts of Gera, Erfurt, and Suhl had significant amounts of former Nazi Party members in their government.[55]

British zone

The British prepared a plan from 1942 onwards, assigning a number of quite junior civil servants to head the administration of liberated territory in the rear of the Armies, with draconian powers to remove from their post, in both public and private domains, anyone suspected, usually on behavioral grounds, of harboring Nazi sympathies. For the British government, the rebuilding of German economic power was more important than the imprisonment of Nazi criminals.[59] Economically hard pressed at home after the war, they did not want the burden of feeding and otherwise administering Germany.[60]

In October 1945, in order to constitute a working legal system, and given that 90% of German lawyers had been members of the Nazi Party, the British decided that 50% of the German Legal Civil Service could be staffed by "nominal" Nazis. Similar pressures caused them to relax the restriction even further in April 1946.[61] In industry, especially in the economically crucial Ruhr area, the British began by being lenient about who owned or operated businesses, turning stricter by autumn of 1945. To reduce the power of industrialists, the British expanded the role of trade unions, giving them some decision-making powers.[62]

They were, however, especially zealous during the early months of occupation in bringing to justice anyone, soldiers or civilians, who had committed war crimes against POWs or captured Allied aircrew.[63] In June 1945 an interrogation center at Bad Nenndorf was opened, where detainees were allegedly tortured via buckets of cold water, beatings, being burnt with lit cigarettes, etc. A public scandal ensued, with the center eventually being closed down.[64]

The British to some extent avoided being overwhelmed by the potential numbers of denazification investigations by requiring that no one need fill in the Fragebogen unless they were applying for an official or responsible position. This difference between American and British policy was decried by the Americans and caused some Nazis to seek shelter in the British zone.[65]

In January 1946, the British handed over their denazification panels to the Germans.[66]

French zone

The French were less vigorous, for a number of reasons, than the other Western powers, not even using the term "denazification", instead calling it "épuration" (purification). At the same time, some French occupational commanders had served in the collaborationist Vichy regime during the war where they had formed friendly relationships with Germans. As a result, in the French zone mere membership in the Nazi Party was much less important than in the other zones.[67]

Because teachers had been strongly Nazified, the French began by removing three-quarters of all teachers from their jobs. However, finding that the schools could not be run without them, they were soon rehired, although subject to easy dismissal. A similar process governed technical experts.[68] The French were the first to turn over the vetting process to Germans, while maintaining French power to reverse any German decision. Overall, the business of denazification in the French zone was considered a "golden mean between an excessive degree of severity and an inadequate standard of leniency", laying the groundwork for an enduring reconciliation between France and Germany. In the French zone only thirteen Germans were categorized as "major offenders".[69]

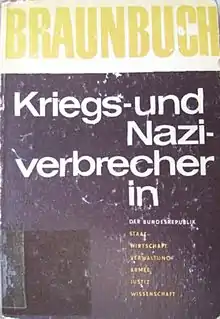

Brown Book

Braunbuch — Kriegs- und Naziverbrecher in der Bundesrepublik: Staat - Wirtschaft - Verwaltung - Armee - Justiz - Wissenschaft (English title: Brown Book — War and Nazi Criminals in the Federal Republic: State, Economy, Administration, Army, Justice, Science) is a book written by Albert Norden in 1965. In this book Norden detailed 1,800 Nazis who maintained high-ranking positions in postwar West Germany.[70]

Altogether 1,800 West German persons and their past were covered: especially 15 Ministers and state secretaries, 100 admirals and generals, 828 judges or state lawyers and high law officers, 245 officials of the Foreign Office and of embassies and consulates in leading position, 297 high police officers and officers of the Verfassungsschutz. The first brown book was seized in West Germany — on Frankfurt Book Fair — by judicial resolution.[71]

The contents of this book received substantial attention in West Germany and other countries. The West German government stated, at that time, that it was "all falsification".[72] Later on, however, it became clear that the data of the book were largely correct. Hanns Martin Schleyer, for example, really had been a member of the SS. The book was translated into 10 languages. Amongst the reactions to it was also a similar West German book of the same name, covering the topic of Nazis re-emerging in high-level positions in the GDR.[73]

In addition to the Braunbuch the educational booklet Das ganze System ist braun (The whole system is brown) was published in the GDR.[74]

Responsibility and collective guilt

The ideas of collective guilt and collective punishment originated not with the US and British people, but on higher policy levels.[76] Not until late in the war did the US public assign collective responsibility to the German people.[76] The most notable policy document containing elements of collective guilt and collective punishment is JCS 1067 from early 1945.[76] Eventually horrific footage from the concentration camps would serve to harden public opinion and bring it more in line with that of policymakers.[76]

Already in 1944, prominent US opinion makers had initiated a domestic propaganda campaign (which was to continue until 1948) arguing for a harsh peace for Germany, with a particular aim to end the apparent habit in the US of viewing the Nazis and the German people as separate entities.[77]

Statements made by the British and US governments, both before and immediately after Germany's surrender, indicate that the German nation as a whole was to be held responsible for the actions of the Nazi regime, often using the terms "collective guilt" and "collective responsibility".[78]

To that end, as the Allies began their post-war denazification efforts, the Psychological Warfare Division (PWD) of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force undertook a psychological propaganda campaign for the purpose of developing a German sense of collective responsibility.[79]

The Public Relations and Information Services Control Group of the British Element (CCG/BE) of the Allied Control Commission for Germany began in 1945 to issue directives to officers in charge of producing newspapers and radio broadcasts for the German population to emphasize "the moral responsibility of all Germans for Nazi crimes".[80] Similarly, among US authorities, such a sense of collective guilt was "considered a prerequisite to any long-term education of the German people".[79]

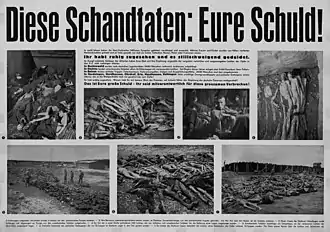

Using the German press, which was under Allied control, as well as posters and pamphlets, a program was conducted to acquaint ordinary Germans with what had taken place in the concentration camps. For example, using posters with images of concentration camp victims coupled to text such as "YOU ARE GUILTY OF THIS!"[81][82] or "These atrocities: your fault!"[Notes 2]

English writer James Stern recounted an example in a German town soon after the German surrender:

[a] crowd is gathered around a series of photographs which though initially seeming to depict garbage instead reveal dead human bodies. Each photograph has a heading "WHO IS GUILTY?". The spectators are silent, appearing hypnotised and eventually retreat one by one. The placards are later replaced with clearer photographs and placards proclaiming "THIS TOWN IS GUILTY! YOU ARE GUILTY!"[83]

The introduction text of one pamphlet published in 1945 by the American War Information Unit (Amerikanischen Kriegsinformationsamt) entitled Bildbericht aus fünf Konzentrationslagern (Photo Report from Five Concentration Camps) contained this explanation of the pamphlet's purpose:[84][85]

Thousands of Germans who live near these places were led through the camps to see with their own eyes which crimes were committed in their name. But it is not possible for most Germans to view a KZ. This pictorial report is intended for them.[86]

A number of films showing the concentration camps were made and screened to the German public, such as Die Todesmühlen, released in the US zone in January 1946, and Welt im Film No. 5 in June 1945. A film that was never finished due partly to delays and the existence of the other films was Memory of the Camps. According to Sidney Bernstein, chief of Psychological Warfare Division, the objective of the film was:

To shake and humiliate the Germans and prove to them beyond any possible challenge that these German crimes against humanity were committed and that the German people – and not just the Nazis and SS – bore responsibility.[87]

Immediately upon the liberation of the concentration camps, many German civilians were forced to see the conditions in the camps, bury rotting corpses and exhume mass graves.[88] In some instances, civilians were also made to provide items for former concentration camp inmates.[88]

Surveys

The US conducted opinion surveys in the American zone of occupied Germany.[89] Tony Judt, in his book Postwar: a History of Europe since 1945, extracted and used some of them.[90]

- A majority in the years 1945–1949 stated Nazism to have been a good idea but badly applied.[89]

- In 1946, 6% of Germans said the Nuremberg trials had been unfair.[89]

- In 1946, 37% in the US occupation zone said about the Holocaust that "the extermination of the Jews and Poles and other non-Aryans was necessary for the security of Germans".[89]

- In 1946, 1 in 3 in the US occupation zone said that Jews should not have the same rights as those belonging to the Aryan race.[89]

- In 1950, 1 in 3 said the Nuremberg trials had been unfair.[89]

- In 1952, 37% said Germany was better off without the Jews on its territory.[89]

- In 1952, 25% had a good opinion of Hitler.[89]

British historian Ian Kershaw in his book The "Hitler Myth": Image and Reality in the Third Reich[91] writes about the various surveys carried out at the German population:

- In 1945, 42% of young Germans and 22% of adult Germans thought that the reconstruction of Germany would be best applied by a "strong new Führer".

- In 1952, 10% of Germans thought that Hitler was the greatest statesman and that his greatness would only be realized at a later date; and 22% thought he had made "some mistakes" but was still an excellent leader.

- In 1953, 14% of Germans said they would vote for someone like Hitler again.

However, in Hitler, Germans, and the "Jewish Question", Sarah Ann Gordon notes the difficulty of drawing conclusions from the surveys. For example, respondents were given three alternatives from which to choose, as in question 1:

| Statement | Percentage agreeing |

|---|---|

| Hitler was right in his treatment of the Jews: | 0% |

| Hitler went too far in his treatment of the Jews, but something had to be done to keep them in bounds: | 19% |

| The actions against the Jews were in no way justified: | 77% |

To the question of whether an Aryan who marries a Jew should be condemned, 91% responded "No". To the question of whether "All those who ordered the murder of civilians or participated in the murdering should be made to stand trial", 94% responded "Yes".[92]

Gordon singles out the question "Extermination of the Jews and Poles and other non-Aryans was not necessary for the security of the Germans", which included an implicit double negative to which the response was either yes or no. She concludes that this question was confusingly phrased (given that in the German language the affirmative answer to a question containing a negative statement is "no"): "Some interviewees may have responded 'no' they did not agree with the statement, when they actually did agree that the extermination was not necessary."[93] She further highlights the discrepancy between the antisemitic implications of the survey results (such as those later identified by Judt) with the 77% percent of interviewees who responded that actions against Jews were in no way justified.[93]

Gordon states that if the 77 percent result is to be believed then an "overwhelming majority" of Germans disapproved of extermination, and if the 37 percent result is believed to be correct then over one third of Germans were willing to exterminate Poles and Jews and others for German security.[93] She concludes that the phrasing of the question on German security lowers the confidence in the latter interpretation.[93]

Gordon follows this with another survey where interviewees were asked if Nazism was good or bad (53% chose bad) and reasons for their answer. Among the nine possible choices on why it was bad, 21% chose the effects on the German people before the war, while 3–4 percent chose the answer "race policy, atrocities, pogroms".[93] However, Gordon highlights the issue that it is difficult to pin down at which point in time respondents became aware of the exterminations, before or after they were interviewed: questionnaire reports indicate that a significant minority claimed they had had no knowledge until the Nuremberg trials.

She also notes that when confronted with the exterminations there was an element of denial, disbelief, and confusion. Asked about concentration camps, very few Germans associated them with the Jews, leading to the conclusion that they did not understand how they had been used against the Jews during the war and instead continued to think of them as they were before the war, the place where political opponents to the Nazis were kept. "This naivete is only understandable if large numbers of Germans were truly ignorant of the existence of these camps".[94] A British study on the same attitudes concluded that

Those who said National Socialism was a good idea pointed to social welfare plans, the lack of unemployment, the great construction plans of the Nazis ... Nearly all those who thought it a good idea nevertheless rejected Nazi racial theories and disagreed with the inhumanity of the concentration camps and the 'SS'.[94]

Sarah Gordon writes that a majority of Germans appeared to approve of nonviolent removal of Jews from civil service and professions and German life.[93] The German public also accepted the Nuremberg laws because they thought they would act as stabilizers and end violence against Jews.[94] The German public had as a result of the Nazi antisemitic propaganda hardened their attitudes between 1935 and 1938 from the originally favorable stance. By 1938, the propaganda had taken effect and antisemitic policies were accepted, provided no violence was involved.[94] Kristallnacht caused German opposition to antisemitism to peak, with the vast majority of Germans, including Nazis, rejecting the violence and destruction, and many Germans aiding the Jews.[95]

The Nazis responded by intimidation in order to discourage opposition, those aiding Jews being victims of large-scale arrests and intimidation.[94] With the start of the war the antisemitic minority that approved of restrictions on Jewish domestic activities was growing, but there is no evidence that the general public had any acceptance for labor camps or extermination.[94] As the number of antisemites grew, so too did the number of Germans opposed to racial persecution, and rumors of deportations and shootings in the east led to snowballing criticism of the Nazis. Gordon states that "one can probably conclude that labor camps, concentration camps, and extermination were opposed by a majority of Germans".[94]

Gordon concludes in her analysis on German public opinion based German SD-reports during the war and the Allied questionnaires during the occupation:

it would appear that a majority of Germans supported elimination of Jews from the civil service; quotas on Jews in professions, academic institutions, and commercial fields; restrictions on intermarriage; and voluntary emigration of Jews. However, the rabid antisemites' demands for violent boycotts, illegal expropriation, destruction of Jewish property, pogroms, deportation, and extermination were probably rejected by a majority of Germans. They apparently wanted to restrict Jewish rights substantially, but not to annihilate Jews.[94]

End

_had_besprekingen_met_Kiesinger_te_Bonn%252C_Johnson_en_Kiesi%252C_Bestanddeelnr_920-2595.jpg.webp)

The West German political system, as it emerged from the occupation, was increasingly opposed to the Allied denazification policy.[96] As denazification was deemed ineffective and counterproductive by the Americans, they did not oppose the plans of the West German chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, to end the denazification efforts. Adenauer's intention was to switch government policy to reparations and compensation for the victims of Nazi rule (Wiedergutmachung), stating that the main culprits had been prosecuted.[97] In 1951 several laws were passed, ending the denazification. Officials were allowed to retake jobs in the civil service, and hiring quotas were established for these previously-excluded individuals,[98] with the exception of people assigned to Group I (Major Offenders) and II (Offenders) during the denazification review process. These individuals were referred to as "131-ers", after Article 131 of Federal Republic’s Basic Law.[99][100]

Several amnesty laws were also passed which affected an estimated 792,176 people. Those pardoned included people with six-month sentences, 35,000 people with sentences of up to one year and include more than 3,000 functionaries of the SA, the SS, and the Nazi Party who participated in dragging victims to jails and camps; 20,000 other Nazis sentenced for "deeds against life" (presumably murder); 30,000 sentenced for causing bodily injury, and 5,200 who committed "crimes and misdemeanors in office".[101] As a result, many people with a former Nazi past ended up again in the political apparatus of West Germany. In 1957, 77% of the German Ministry of Justice's senior officials were former Nazi Party members.[102]

Hiding one's Nazi past

Membership in Nazi organizations is still not an open topic of discussion. German President Walter Scheel and Chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger were both former members of the Nazi Party. In 1950, a major controversy broke out when it emerged that Konrad Adenauer's State Secretary Hans Globke had played a major role in drafting antisemitic Nuremberg Race Laws in Nazi Germany.[103] In the 1980s former UN Secretary General and President of Austria Kurt Waldheim was confronted with allegations he had lied about his wartime record in the Balkans.

It was not until 2006 that famous German writer Günter Grass, occasionally viewed as a spokesman of "the nation's moral conscience", spoke publicly about the fact that he had been a member of the Waffen-SS – he was conscripted into the Waffen-SS while barely seventeen years old and his duties were military in nature. Statistically, it was likely that there were many more Germans of Grass's generation (also called the "Flakhelfer-Generation") with biographies similar to his.[104]

Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI), on the other hand, was open about his membership at the age of fourteen of the Hitler Youth, when his church youth group was forced to merge with them.[105]

In other countries

In practice, denazification was not limited to Germany and Austria. In several European countries with a vigorous Nazi or fascist party, measures of denazification were carried out. In France the process was called épuration légale (legal cleansing). Prisoners of war held in detention in Allied countries were also subject to denazification qualifications before being returned to their countries of origin.

Denazification was also practiced in many countries which came under German occupation, including Belgium, Norway, Greece and Yugoslavia, because satellite regimes had been established in these countries with the support of local collaborators.

In Greece, for instance, Special Courts of Collaborators were created after 1945 to try former collaborators. The three Greek "quisling" prime ministers were convicted and sentenced to death or life imprisonment. Other Greek collaborators after German withdrawal underwent repression and public humiliation, besides being tried (mostly on treason charges). In the context of the emerging Greek Civil War, however, most wartime figures from the civil service, the Greek Gendarmerie and the notorious Security Battalions were quickly integrated into the strongly anti-Communist postwar establishment.

An attempt to ban the swastika across the EU in early 2005 failed after objections from the British government and others. In early 2007, while Germany held the European Union presidency, Berlin proposed that the European Union should follow German Criminal Law and criminalize the denial of the Holocaust and the display of Nazi symbols including the swastika, which is based on the Ban on the Symbols of Unconstitutional Organizations Act (Strafgesetzbuch section 86a). This led to an opposition campaign by Hindu groups across Europe against a ban on the swastika. They pointed out that the swastika has been around for 5,000 years as a symbol of peace.[106][107] The proposal to ban the swastika was dropped by the German government from the proposed European Union wide anti-racism laws on January 29, 2007.[108]

See also

- Collaboration with the Axis powers

- Damnatio memoriae

- De-Ba'athification

- Decommunization

- De-Francoization

- De-Stalinization

- Fascist (insult)

- German resistance to Nazism

- Gleichschaltung, the "Nazification" of Germany in the 1930s

- Historical Memory Law

- Holocaust trivialization

- List of streets named after Adolf Hitler

- Lustration

- Neulehrer

- Pursuit of Nazi collaborators

- Secondary antisemitism

- Street name controversy

- Transitional justice

- Vergangenheitsbewältigung

- Japanese People's Anti-war Alliance

- Japanese People's Emancipation League

Notes

- In August 1946 the order was amended so that "In the interest of research and scholarship, the Zone Commanders (in Berlin the Komendantura) may preserve a limited number of documents prohibited in paragraph 1. These documents will be kept in special accommodation where they may be used by German scholars and other German persons who have received permission to do so from the Allies only under strict supervision by the Allied Control Authority."

- Eric Voegelin, Brenden Purcell "Hitler and the Germans", Footnote 12, p. 5 "In the summer of 1945, the Allies publicly displayed horrifying posters and reports from the Dachau and Belsen concentration camps with the accusatory headline 'Diese Schandtaten: Eure Schuld!' ('These atrocities: Your fault!')." See Christoph Klessmann, Die doppelte Staatsgrundung: Deutsche Geschichte, 1945–1955'., p. 308

References

- Taylor, Frederick (2011). Exorcising Hitler: The Occupation and Denazification of Germany. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 253–254. ISBN 978-1408822128.

- Goda, Norman J. W. (2007). Tales from Spandau: Nazi Criminals and the Cold War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 101–149. ISBN 978-0-521-86720-7.

- Jacobsen, Annie (2014). Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program that Brought Nazi Scientists to America. bpb.

- Benz, Wolfgang (2005). Demokratisierung durch Entnazifizierung und Erziehung. bpb. p. 7.

- Sperk, Alexander (2003). Entnazifizierung und Personalpolitik in der sowjetischen Besatzungszone Köthen/Anhalt. Eine Vergleichsstudie (1945–1948) [Denazification and personal politics in the Soviet Occupied Zone of Köthen/Anhalt. A comparative study (1945–1948).] (in German). Dößel: Verlag Janos Stekovics. ISBN 3-89923-027-2.

- Kai Cornelius, Vom spurlosen Verschwindenlassen zur Benachrichtigungspflicht bei Festnahmen, BWV Verlag, 2004, pp. 126ff, ISBN 3-8305-1165-5

- Taylor (2011), p. 256.

- Taylor, Frederick (2011). Exorcising Hitler: The Occupation and Denazification of Germany. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 226. ISBN 978-1408822128.

- Taylor, Frederick (2011). Exorcising Hitler: The Occupation and Denazification of Germany. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 255. ISBN 978-1408822128.

- Taylor, Frederick (2011). Exorcising Hitler: The Occupation and Denazification of Germany. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 119–123. ISBN 978-1408822128.

- Taylor, Frederick (2011). Exorcising Hitler: The Occupation and Denazification of Germany. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 97-98. ISBN 978-1408822128.

- Taylor, Frederick (2011). Exorcising Hitler: The Occupation and Denazification of Germany. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 258. ISBN 978-1408822128.

- Taylor, Frederick (2011). Exorcising Hitler: The Occupation and Denazification of Germany. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 230. ISBN 978-1408822128.

- Taylor, Frederick (2011). Exorcising Hitler: The Occupation and Denazification of Germany. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 231. ISBN 978-1408822128.

- Taylor, Frederick (2011). Exorcising Hitler: The Occupation and Denazification of Germany. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 267. ISBN 978-1408822128.

- Taylor, Frederick (2011). Exorcising Hitler: The Occupation and Denazification of Germany. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 300. ISBN 978-1408822128.

- Taylor (2011), p. 253.

- Adam, p. 274

- Norgaard, Noland. (October 13, 1945). "Eisenhower Claims 50 Years Needed to Re-Educate Nazis". The Oregon Statesman. p. 2. Retrieved November 9, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- Taylor (2011), pp. 249–252.

- Taylor (2011), pp. 261–262.

- Taylor (2011), p. 266.

- Taylor (2011), p. 267.

- Taylor (2011), p. 268.

- Taylor (2011), p. 278.

- Taylor (2011), pp. 271–273.

- Junker, p. 68

- Taylor (2011), p. 281.

- Taylor (2011), p. 282.

- Adam, p. 275

- Control Council Directive No. 38, Articles 7–13 (October 12, 1946)

- Taylor (2011), p. 283.

- Adam, p. 275. Also see Katrin Himmler's book "The Brothers Himmler", about the Himmler family

- Taylor (2011), p. 290

- Taylor (2011), p. 284.

- Taylor (2011), p. 285.

- Herbert Hoover's press release of The President's Economic Mission to Germany and Austria, Report No. 1: German Agriculture and Food Requirements Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, February 28, 1947. p. 2

- Beattie 2019.

- Taylor (2011), p. 277.

- Steven Bela Vardy and T. Hunt Tooley, eds. Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe Archived December 1, 2007, at the Wayback Machine ISBN 0-88033-995-0. Subsection by Richard Dominic Wiggers, "The United States and the Refusal to Feed German Civilians after World War II" p. 281

- JAMES L. PAYNE. "Did the United States Create Democracy in Germany?" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- "McClure article". Archived from the original on November 15, 2006. Retrieved October 22, 2006.

- "Lochner interview".

- "Germany: Read No Evil". Time. New York. May 27, 1946. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- Cora Goldstein "PURGES, EXCLUSIONS, AND LIMITS: ART POLICIES IN GERMANY 1933–1949, "Cultural Policy Program". Archived from the original on December 23, 2007. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- Theodore Ziolkowski (May 17, 1981). "Historical Analogy". New York Times. Retrieved November 4, 2007.

- Doris Betzl (April 3, 2003). "Geburt als Skorpion, Tod als Papiertiger". Rezensionsforum Literaturkritik, No. 4 (in German). Literaturkritik DE. Archived from the original on January 14, 2006. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- Did the United States Create Democracy in Germany? the Independent Institute

- Dieter Schenk: Auf dem rechten Auge blind. Köln 2001.

- Ritscher, Bodo (1999). Das Speziallager Nr. 2 1945–1950. Katalog zur ständigen historischen Ausstellung [Special Camp No. 2 1945–1950. A catalog of the historical site.]. Wallstein Verlag. ISBN 3-89244-284-3.

- Taylor (2011), pp. 236–241.

- van Mells, Damian (1999). Entnazifizierung in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern: Herrschaft und Verwaltung 1945–1948 [Denazification in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern: Rule and Administration 1945–1948]. Walter de Gruyter GmbH. p. 208. ISBN 3-486-56390-4.

- Ralph Giordano Die zweite Schuld. Köln 2000.

- Vollnhals, Clemens (1995). Entnazifizierung, Politische Säuberung unter alliierter Herrschaft [Denazification, Political cleansing under Allied administration]. Munich. p. 377. ISBN 3-492-12056-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wolle, Stefan (2013). Der große Plan - Alltag und Herrschaft in der DDR 1949–1961 [The Greatest Plan: Everyday life and governance in the GDR 1949–1961]. Christoph Links Verlag. pp. 205–207. ISBN 978-3-86153-738-0.

- "Rare East German Photographs: The Other Side of the Berlin Wall". Spiegel Online. 2011. Retrieved July 2, 2013.

- Weinke, Annette (2002). Die Verfolgung von NS-Tätern im geteilten Deutschland. Schöningh. p. 157. ISBN 978-3506797247.

- Tillack-Graf, Anne-Kathleen (2012). Erinnerungspolitik der DDR. Dargestellt an der Berichterstattung der Tageszeitung "Neues Deutschland" über die Nationalen Mahn- und Gedenkstätten Buchenwald, Ravensbrück und Sachsenhausen. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-3-631-63678-7.

- Wierskalla, Sven (2007). Die Vereinigung der Verfolgten des Naziregimes (VNN) in der Sowjetischen Besatzungszone und in Berlin 1945 bis 1948. Grin Verlag. p. 103.

- Taylor (2011), p. 299.

- Taylor (2011), p. 265.

- Taylor (2011), pp. 307–308.

- Taylor (2011), pp. 293–295.

- Taylor (2011), p. 305.

- Taylor (2011), pp. 302–303, 310.

- Taylor (2011), p. 303.

- Taylor (2011), pp. 317–321.

- Taylor (2011), p. 321.

- Taylor (2011), p. 322.

- Norden, Albert (1965). Braunbuch.Kriegs-und Naziverbrecher in der Bundesrepublik. Staatsverlag der DDR.

- Ditfurth, Jutta (2007). Ulrike Meinhof: Die Biography. Ullstein. ISBN 978-3-550-08728-8. pp. 274–275 (Greek version)

- Dieter Schenk, Auf dem rechten Auge blind. Die braunen Wurzeln des BKA (Kiepenheuer & Witsck, Köln 2001)

- Olaf Kappelt: Braunbuch DDR. Nazis in der DDR. Reichmann Verlag, Berlin (West) 1981. ISBN 3-923137-00-1

- Tillack-Graf, Anne-Kathleen (2012). Erinnerungspolitik der DDR. Dargestellt an der Berichterstattung der Tageszeitung "Neues Deutschland" über die Nationalen Mahn- und Gedenkstätten Buchenwald, Ravensbrück und Sachsenhausen. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. p. 48. ISBN 978-3-631-63678-7.

- Jeffrey K. Olick, "In the house of the hangman: the agonies of German defeat, 1943–1949", p. 98, footnote 12(books google)

- Nicosia, Francis R.; Huener, Jonathan (2004). Business and Industry in Nazi Germany (1 ed.). Berghahn Books. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-1-57181-653-5. JSTOR j.ctt1x76ff3.

- Steven Casey, (2005), The Campaign to sell a harsh peace for Germany to the American public, 1944–1948, [online]. London: LSE Research Online. [Available online at http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/archive/00000736 Archived January 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine] Originally published in History, 90 (297). pp. 62–92 (2005) Blackwell Publishing, "Indeed, in 1944 their main motive for launching a propaganda campaign was to try to put an end to the persistent American habit 'of setting the Nazis apart from the German people'".

- Balfour, Michael Leonard Graham; Balfour, Michael (1988). Withstanding Hitler in Germany, 1933-45. Routledge. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-415-00617-0.

- Janowitz, Morris (1946). "German Reactions to Nazi Atrocities". American Journal of Sociology. 52 (2): 141–146. doi:10.1086/219961. ISSN 0002-9602. JSTOR 2770938. PMID 20994277. S2CID 44356394.

- Balfour, Michael Leonard Graham; Balfour, Michael (1988). Balfour, p. 263. Routledge. ISBN 9780415006170.

- Marcuse, Harold (March 22, 2001). Marcuse, p. 61. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521552042.

- "NEVER AGAIN!: A review of David Goldhagen, Hitlers Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust (London, 1997)". pubs.socialistreviewindex.org.uk. Archived from the original on August 22, 2003. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- Therese O'Donnell Executioners, bystanders and victims: collective guilt, the legacy of denazification and the birth of twentieth-century transitional justice, Legal Studies Volume 25 Issue 4, pp. 627–667

- Marcuse, Harold (March 22, 2001). Marcuse, p. 426, footnote 77. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521552042.

- Bildbericht aus fünf Konzentrationslagern [Photo Report from Five Concentration Camps] (pamphlet) (in German), Amerikanischen Kriegsinformationsamt, 1945, 32 pages. 2006 reconstruction Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine available online by the Association of Persecutees of the Nazi Regime/Federation of Antifascists of North Rhine-Westphalia (Vereinigung der Verfolgten des Naziregimes – Bund der Antifaschistinnen und Antifaschisten Nordrhein-Westfalen) (VVN-BdA)

- Original German: "Tausende von Deutschen, die in der Nähe dieser Orte leben, wurden durch die Lager geführt, um mit eigenen Augen zu sehen, welche Verbrechen dort in ihrem Namen begangen worden sind. Aber für die meisten Deutschen ist es nicht möglich, ein K.Z. zu besichtigen. Für sie ist dieser Bildbericht bestimmt."

- "Frequently Asked Questions | Memory Of The Camps | FRONTLINE | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- Marcuse, Harold (March 22, 2001). Marcuse, p. 128. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521552042.

- Judt, Tony (2007), Postwar: a History of Europe since 1945, Pimlico, p. 58, ISBN 978-1446418024

- Judt Book Review Archived July 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Ian Kershaw (2001). The "Hitler Myth": Image and Reality in the Third Reich. Oxford University Press. pp. 264–66. ISBN 0192802062.

- Gordon, Sarah Ann (March 1, 1984). Hitler, Germans, and the "Jewish Question". Princeton University Press. pp. 202–205. ISBN 0-691-10162-0.

- Gordon, Sarah Ann (March 1, 1984). Hitler, Germans, and the "Jewish Question". Princeton University Press. pp. 199–200. ISBN 0-691-10162-0.

- Gordon, Sarah Ann (March 1, 1984). Hitler, Germans, and the "Jewish Question". Princeton University Press. pp. 201–208. ISBN 0-691-10162-0.

- Gordon, Sarah Ann (March 1, 1984). Hitler, Germans, and the "Jewish Question". Princeton University Press. pp. 201–208, 263-270. ISBN 0-691-10162-0.

- Frei, Norbert (1996). Vergangenheitspolitik: Die Anfänge der Bundesrepublik und die NS-Vergangenheit. C.H.Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-63661-5.

- Steinweis, Alan E.; Rogers, Daniel E., eds. (2003). The Impact of Nazism: New Perspectives on the Third Reich and Its Legacy. University of Nebraska Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0803222397.

- Gassert, Philipp (2006). Coping with the Nazi Past: West German Debates on Nazism and Generational Conflict, 1955-1975. Berghahn Books. p. 98. ISBN 1845450868.

- Art, David (2005). The Politics of the Nazi Past in Germany and Austria. Cambridge University Press. pp. 53–55. ISBN 978-0521673242.

- "Gesetz zur Regelung der Rechtsverhältnisse der unter Artikel 131 des Grundgesetzes fallenden Personen – 11 May 1951 (Bundesgesetzblatt I 22/1951, p. 307 ff.)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 6, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- Herf, Jeffrey (March 10, 2003). "Amnesty and Amnesia". The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- "Germany's post-war justice ministry was infested with Nazis protecting former comrades, study reveals". The Daily Telegraph. October 10, 2016. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022.

- Tetens, T.H. The New Germany and the Old Nazis, New York: Random House, 1961 pp. 37–40.

- Margolis, Karen (November 4, 2007). "Who wasn't a Nazi?". Mut gegen rechte Gewalt. Stern.

- Bernstein, Richard; Landler, Mark (April 21, 2005). "POPE BENEDICT XVI: THE NAZI YEARS; Few See Taint in Service By Pope in Hitler Youth". The New York Times. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- "Hindus opposing EU swastika ban". BBC News. January 17, 2007. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- "Hindus Against Proposed EU Swastika Ban". Der Spiegel. Hamburg, Germany. Reuters. January 17, 2007. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- McNern, Ethan (January 30, 2007). "Swastika ban left out of EU's racism law". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Archived from the original on August 5, 2011.

Further reading

- Adam, Thomas (2005). Germany and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History: A Multidisciplinary Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-628-0.

- Balfour, Michael Leonard Graham (1988). Withstanding Hitler in Germany, 1933–45. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00617-1.

- Beattie, Andrew H. (2019). Allied Internment Camps in Occupied Germany: Extrajudicial Detention in the Name of Denazification, 1945–1950. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108487634.

- Biddiscombe, Perry (2006). The Denazification of Germany 1945–48. The History Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7524-2346-3.

- The Department of State (1950). Germany 1947–1949: The Story In Documents. Archived from the original on April 20, 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Goldhagen, Daniel J. (1997). Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-77268-5.

- Hentschel, Klaus (2007). The Mental Aftermath: The Mentality of German Physicists 1945–1949. Ann M. Hentschel as translator. Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-920566-0.

- Howard, Lawrence E. (United States Army Reserve) (March 30, 2007). "Lessons Learned from Denazification and de-Ba'athification (strategy research project for a master of strategic studies degree)" (PDF). US Army War College. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 30, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- Janowitz, Morris (September 1946). "German Reactions to Nazi Atrocities". The American Journal of Sociology. The University of Chicago Press. 52 (2): 141–146. doi:10.1086/219961. JSTOR 2770938. PMID 20994277. S2CID 44356394.

- Junker, Detlef (2004). The United States and Germany in the Era of the Cold War: A Handbook. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79112-0.

- Lewkowicz, N. The German Question and the Origins of the Cold War (IPOC:Milan) (2008)

- Marcuse, Harold (2001). Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933–2001. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55204-4.

- Merritt, Anna J.; Merritt, Richard L.; United States. Office of High Commissioner for Germany. Reactions Analysis Staff (1980). Public opinion in semisovereign Germany : the HICOG surveys, 1949–1955. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-00731-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Taylor, Frederick (2011). Exorcising Hitler: The Occupation and Denazification of Germany. Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-60819-503-9.

External links

- Did the United States Create Democracy in Germany? (Analysis on Denazification effect)

- Control Council Directive No. 38 (October 12, 1946) Categories of offenders and sanctions.

- Example of a poster used by US forces to create "collective guilt" Archived October 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- THE U.S. MILITARY GOVERNMENT AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF DEMOCRATIC REFORM, FEDERALISM, AND CONSTITUTIONALISM DURING THE OCCUPATION OF BAVARIA, 1945–47

- The Denazification of Austria by France

- Denazification, cumulative review. Report, 1 April 1947 – 30 April 1948.

- East Germany did face up to its Nazi past