Italo Balbo

Italo Balbo (6 June 1896 – 28 June 1940) was an Italian fascist politician and Blackshirts' leader who served as Italy's Marshal of the Air Force, Governor-General of Italian Libya and Commander-in-Chief of Italian North Africa. Due to his young age, he was sometimes seen as a possible successor of dictator Benito Mussolini.

Italo Balbo | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Governor-General of Italian Libya | |

| In office 1 January 1934 – 28 June 1940 | |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Rodolfo Graziani |

| Minister of the Air Force | |

| In office 12 September 1929 – 6 November 1933 | |

| Prime Minister | Benito Mussolini |

| Preceded by | Benito Mussolini |

| Succeeded by | Benito Mussolini |

| Quadrumvir in the Grand Council of Fascism | |

| In office 12 January 1923 – 28 June 1940 | |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 24 May 1924 – 2 March 1939 | |

| Constituency | Emilia-Romagna |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 6 June 1896 Ferrara, Kingdom of Italy |

| Died | 28 June 1940 (aged 44) Tobruk, Italian Libya |

| Political party | Italian Fasces of Combat (1919–1921) National Fascist Party (1921–1940) |

| Spouse |

Emanuela Florio (m. 1924) |

| Children | 3 |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | MVSN Regia Aeronautica |

| Years of service | 1915–1940 |

| Rank | Maresciallo dell'Aria (Marshal of the Air Force) |

| Battles/wars | World War I: |

After serving in World War I, Balbo became the leading Fascist party organizer in his home region of Ferrara. He was one of the Quadrumvirs the four principal architects (Quadrumviri del Fascismo) of the March on Rome that brought Mussolini and the Fascists to power in 1922, along with Michele Bianchi, Emilio De Bono and Cesare Maria De Vecchi. In 1926, he began the task of building the Italian Royal Air Force and took a leading role in popularizing aviation in Italy, and promoting Italian aviation to the world. In 1933, perhaps to relieve tensions surrounding him in Italy, he was given the government of Italian Libya, where he resided for the remainder of his life. Balbo, hostile to antisemitism,[1] was among a minority of leading Fascists to oppose Mussolini's alliance with Nazi Germany.[2] Early in World War II, he was accidentally killed by friendly fire when his plane was shot down over Tobruk by Italian anti-aircraft guns who misidentified it.[3]

Early life

.jpg.webp)

In 1896, Balbo was born in Quartesana (part of Ferrara) in the Kingdom of Italy. Balbo was very politically active from an early age. At 14 years of age, he attempted to join in a revolt in Albania under Ricciotti Garibaldi, Giuseppe Garibaldi's son.[4]

As World War I broke out and Italy declared its neutrality, Balbo supported joining the war on the side of the Allies. He joined in several pro-war rallies. Once Italy entered the war in 1915, Balbo joined the Italian Royal Army (Regio Esercito) as an officer candidate and served with the Alpini mountain infantry. His first assignment was with the Alpini Battalion "Val Fella", 8th Alpini Regiment, before volunteering for flight training on 16 October 1917. A few days later the Austro-Hungarian and German armies broke the Italian lines in the Battle of Caporetto, and Balbo returned to the front, now assigned to the Alpini Battalion "Pieve di Cadore", 7th Alpini Regiment, where he took command of an assault platoon. At the end of the war, Balbo had earned one bronze and two silver medals for military valour and reached the rank of Captain (Capitano) due to courage under fire.[2]

After the war, Balbo completed the studies he had begun in Florence in 1914–15. He obtained a law degree and a degree in Social Sciences. His final thesis was written on "the economic and social thought of Giuseppe Mazzini", and he researched under the supervision of the patriotic historian Niccolò Rodolico. Balbo was a Republican, but he hated Socialists and the unions and cooperatives associated with them.

Balbo returned to his home town to work as a bank clerk. In 1920, Balbo was initiated in the regular Masonic Lodge "Giovanni Bovio", affiliated to the Gran Loggia d'Italia. Subsequently, he received the degree of Orator in the Masonic Lodge" Girolamo Savonarola" in Ferrara,[5] joined by various other party officials.[6] He left the lodge on 18 February 1923,[7] just three days before the vote of the Grand Council of Fascism which forbid fascists to be members of the Freemasonry.

Blackshirt leader

In 1921, Balbo joined the newly created National Fascist Party (Partito Nazionale Fascista, or PNF) and soon became a secretary of the Ferrara Fascist organization. He began to organize Fascist gangs and formed his own group nicknamed Celibano, after their favorite drink. They broke strikes for local landowners and attacked communists and socialists in Portomaggiore, Ravenna, Modena, and Bologna. The group once raided the Estense Castle in Ferrara. Italo Balbo had become one of the "Ras", adopted from an Ethiopian title somewhat equivalent to a duke, of the Fascist hierarchy by 1922, establishing his local leadership in the party. The "Ras" typically wished for a more decentralized Fascist Italian state to be formed, against Mussolini's wishes.[8]

At 26 years of age, Balbo was the youngest of the "Quadrumvirs": the four main planners of the "March on Rome." The "Quadrumvirs" were Michele Bianchi (age 39), Cesare Maria De Vecchi (38), Emilio De Bono (56), and Balbo. Mussolini himself (39) would not participate in the risky operation that ultimately brought Italy under Fascist rule.[9] In 1923, as one of the "Quadrumvirs", Balbo became a founding member of the Grand Council of Fascism (Gran Consiglio del Fascismo). This same year, he was implicated in the murder of anti-Fascist parish priest Giovanni Minzoni in Argenta. He fled to Rome and in 1924 became General Commander of the Fascist militia and undersecretary for National Economy in 1925.

Aviator

On 6 November 1926, though he had only a little experience in aviation, Balbo was appointed Secretary of State for Air. He went through an intensive course of flying instruction and began building the Italian Royal Air Force (Regia Aeronautica Italiana). On 19 August 1928, he became General of the Air Force and on 12 September 1929 Minister of the Air Force.

In Italy, this was a time of great interest in aviation. In 1925, Francesco de Pinedo flew a seaplane from Italy to Australia to Japan and back again to Italy. Mario De Bernardi successfully raced seaplanes internationally. In 1928, Arctic explorer Umberto Nobile piloted the airship Italia on a polar expedition.

Balbo himself led some transatlantic flights. The first was the 1930 flight of twelve Savoia-Marchetti S.55 flying boats from Orbetello Seaplane Base, Italy to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil between 17 December 1930 and 15 January 1931.

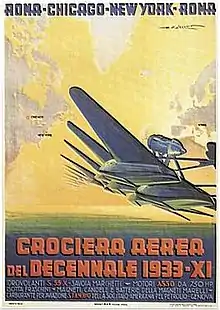

The Crociera del Decennale featured the so-called "Italian Air Armada." From 1 July to 12 August 1933, twenty-four seaplanes flew round-trip from Rome to the Century of Progress in Chicago, Illinois. The flight had eight legs: Orbetello – Amsterdam – Derry – Reykjavík – Cartwright – Shediac – Montreal ending on Lake Michigan near Burnham Park and New York City.[10][11][12] In honor of this feat, Mussolini donated a column from Ostia to the city of Chicago: the Balbo Monument. It can still be seen along the Lakefront Trail, a little south of Soldier Field. Chicago renamed the former 7th Street "Balbo Drive" and staged a great parade in his honor. The Newfoundland Post Office overprinted one of their 75-cent airmail stamps, that had been issued just two months previously, for the event:[13] General Balbo Flight, Labrador, The Land of Gold.[14]

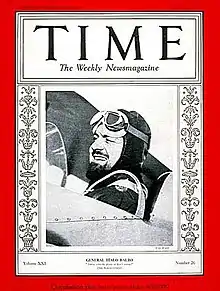

From Chicago they flew to New York City with an escort of 36 U.S. airplanes. New York gave a warm welcome to the pilots on Broadway (Manhattan). Millions of people watched the parade of dozens of cars escorted by police horses along the streets of Manhattan.[15] Balbo was featured on 26 June 1933 cover of Time.[16]

During Balbo's stay in the United States, President Franklin Roosevelt invited him to lunch and presented him with the Distinguished Flying Cross.[17] He was awarded the 1931 Harmon Trophy. The Sioux even honorarily adopted Balbo as "Chief Flying Eagle".[18] Balbo received a warm welcome in the United States, especially by the large Italian-American populations in Chicago and New York City. To a cheering mass in Madison Square Garden he said: "Be proud you are Italians. Mussolini has ended the era of humiliations."[19] The term "Balbo" entered common usage to describe any large formation of aircraft.

The return flight from New York stopped in Shoal Harbour at Clarenville, Newfoundland on 26 July. A road overlooking the bay used by the flying boats was renamed Balbo Drive, a name it still carries today. On 12 August 1933, Balbo's formation departed Clarenville for the Azores, Lisbon, and Rome.[20] Back home in Italy, he was promoted to the newly created rank of Marshal of the Air Force (Maresciallo dell'Aria).

Following his return to Italy, Balbo proposed his vision for a reorganised Italian army. Balbo advocated that the army be reduced to twenty divisions, of which there would be ten motorised, five Alpine and five armoured, all well-equipped, trained and prepared for amphibious warfare, while the navy would have three marine divisions. The idea was that the army would become an expeditionary force that could rapidly deploy by sea or train to Italy's borders (including Libya). However, such a proposal was financially impossible as it would require an unprecedented increase in the defence budget.[21]

Governor of Libya

On 7 November 1933, Balbo was appointed Governor-General of the Italian colony of Libya. Mussolini looked to the flamboyant Air Marshal to be the condottiero of Italian ambition and extend Italy's new horizons in Africa. Balbo's task was to assert Italy's rights in the indeterminate zones leading to Lake Chad from Tummo in the west and from Kufra in the east towards the Sudan. Balbo had already made a flying visit to Tibesti. By securing the "Tibesti-Borku strip" and the "Sarra Triangle", Italy would be in a good position to demand further territorial concessions in Africa from France and Britain. Mussolini even had his sights set on the former German colony of Kamerun. From 1922, the colony had become the League of Nations mandate territories of French Cameroun and British Cameroons. Mussolini pictured an Italian Cameroon and a territorial corridor connecting that territory to Libya. An Italian Cameroon would give Italy a port on the Atlantic Ocean, the mark of a world power. Ultimately, control of the Suez Canal and of Gibraltar would complete the picture.[22]

As of 1 January 1934, Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and Fezzan were merged to form the new colony and Balbo moved to Libya. At that stage, Balbo had apparently caused bad blood in the party, possibly because of jealousy and individualist behavior. Being appointed Governor-General of Libya was an effective exile from politics in Rome where Mussolini considered him a threat,[2] both for his fame and, more importantly, because of his close relationship with the possibly anti-fascist Crown Prince Umberto. Italian newspapers reportedly could not mention Balbo's name more than once a month.[23] "Benito in Balboland," an article in 22 March 1937 issue of Time Magazine, played with the conflict between Mussolini and Balbo. Balbo was still well known in the United States for his visit to the Century of Progress exhibition.[24] While Governor, Balbo ordered Jews who closed their businesses on the Sabbath to be whipped.[25][26] Balbo commissioned the Marble Arch to mark the border between Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. It was unveiled on 16 March 1937.

Abyssinia crisis

In 1935, as the "Abyssinia Crisis" worsened, Balbo began preparing plans to attack Egypt and Sudan. As Mussolini made his intentions to invade Ethiopia clear, relations between Italy and the United Kingdom became more tense. Fearing a "Mad Dog" act by Mussolini against British forces and possessions in the Mediterranean, Britain reinforced its fleet in the region and also its military forces in Egypt. Balbo reasoned that, should Britain choose to close the Suez Canal, Italian troop transports would be prevented from reaching Eritrea and Somalia. Thinking that the planned attack on Abyssinia would be crippled, Balbo asked for reinforcements in Libya. He calculated that such a gesture would make him a national hero and restore him to the centre of the political stage. The 7th Blackshirt Division (Cirene) and 700 aircraft were immediately sent from Italy to Libya. Balbo may have received intelligence concerning the feasibility of advancing into Egypt and Sudan from the famous desert researcher László Almásy.[27]

By 1 September 1935, Balbo secretly deployed Italian forces along the border with Egypt without the British knowing anything about it. At the time, British intelligence concerning what was going on in Libya was woefully inadequate. In the end, Mussolini rejected Balbo's over-ambitious plan to attack Egypt and Sudan and London learned about his deployments in Libya from Rome.[28]

Munich crisis

The "Anglo-Italian Agreement" of April 1938 brought a temporary cessation of tensions between the United Kingdom and the Kingdom of Italy. For Balbo, the agreement meant the immediate loss of 10,000 Italian troops; it was characterised by renewed promises of undertakings that Mussolini had previously broken and he could easily break again. By the time of the "Munich Crisis", Balbo had his 10,000 troops back.[29]

At this time, Italian aircraft were making frequent overflights of Egypt and Sudan and Italian pilots were being familiarised with the routes and airfields. In 1938 and 1939, Balbo himself made a number of flights from Libya across the Sudan to Italian East Africa ('Africa Orientale Italiana', or AOI). He even flew along the border between AOI and British East Africa (modern Kenya). In January 1939, Balbo was accompanied on one of his flights by German Colonel-General Ernst Udet.[29]

There were distinct signs of German military and diplomatic co-operation with the Italians. General Udet was accompanied by the Head of the German Mechanization Department, and the German military attache to Rome paid a long visit to Egypt. A German Military Mission was present in Benghazi and German pilots were engaged in navigational training flights.[29]

Balbo began road construction projects such as the Via Balbia in an attempt to attract Italian immigrants to Libya. He also made efforts to draw Muslims into the Fascist cause. In 1938, Balbo was the only member of the Fascist regime who strongly opposed the new legislation against the Jews, the Italian "Racial Laws".

In 1939, after the German invasion of Poland, Balbo visited Rome to express his displeasure at Mussolini's support for German dictator Adolf Hitler. Balbo was the only Fascist of rank to publicly criticize this aspect of Mussolini's foreign policy. He argued that Italy should side with the United Kingdom, but he attracted little following to his argument. When informed of Italy's formal alliance with Nazi Germany, Balbo exclaimed: "You will all wind up shining the shoes of the Germans!"[2]

World War II

At the time of the Italian declaration of war on 10 June 1940, Balbo was the Governor-General of Libya and Commander-in-Chief of Italian North Africa (Africa Settentrionale Italiana, or ASI). He became responsible for planning an invasion of Egypt. After the surrender of France, Balbo was able to shift much of the men and material of the Italian Fifth Army on the Tunisian border to the Tenth Army on the Egyptian border. While he had expressed many legitimate concerns to Mussolini and to Marshal Pietro Badoglio, the Chief-of-Staff in Rome, Balbo still planned to invade Egypt as early as 17 July 1940.

Death

On 28 June 1940, Balbo was a passenger on a Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 headed for the Libyan airfield of Tobruk, arriving shortly after the airfield had been attacked by British aircraft. Italian anti-aircraft batteries defending the airfield misidentified the aircraft as British, opening fire upon it as it attempted a landing. It was downed and all on board perished.

Eyewitness General Felice Porro reported that the cruiser San Giorgio, serving as a floating anti-aircraft battery, began firing on Balbo's aircraft, followed by the airfield's anti-aircraft guns.[30] It remains unclear which of them ultimately led to his aircraft being downed.

Rumors that Balbo was assassinated on Mussolini's orders have been conclusively debunked.[31][32][33][34] Instead, it is generally accepted that Balbo's aircraft was simply misidentified as an enemy target,[2] as it was flying low and coming in against the sun, in addition to the fact of its arrival shortly after an aerial attack by British Bristol Blenheims.[35]

Upon hearing of the death of Balbo, the Commander-in-Chief of the RAF Middle East Command ordered an aircraft dispatched to fly over the Italian airfield to drop a wreath, with the following note of condolence:

The British Royal Air Force expresses its sympathy in the death of General Balbo – a great leader and gallant aviator, personally known to me, whom fate has placed on the other side. [signed] Arthur Longmore[36]

Balbo's remains were buried outside Tripoli on 4 July 1940. In 1970, Balbo's remains were brought back to Italy and buried in Orbetello by Balbo's family after Muammar Gaddafi threatened to disinter the Italian cemeteries in Tripoli.

Memorial

.jpg.webp)

In 1933, Benito Mussolini presented the city of Chicago with a monument to Balbo. Balbo Drive is a well-known street in the heart of downtown. In 2017, a campaign was launched to rename it.[37][38] After encountering opposition, the city instead elected to rename another street, Congress Parkway, in honor of Ida B. Wells, a leading Chicago journalist, anti-lynching activist and suffragette.[39]

In post-fascist Italy, most monuments and streets named after Balbo during the Fascist Regime reverted to their pre-Fascist names, such as in Palermo, liberated by the Allies in July 1943, where Piazza Italo Balbo reverted to its former name, Piazza Bologna, or were named after anti-fascist partisans, such as in Sanremo, where "Via Italo Balbo" was renamed after partisan Luigi Nuvoloni.[40]

Further reading

- Michel Pratt, Italo Balbo, la traversée de l'Atlantique. 24 hydravions de l'Italie fasciste en Amérique. Éditions Histoire Québec, collection Fédération Histoire Québec, 2014.

Notes

- De Felice, Renzo (2001). The Jews in Fascist Italy: A History. Enigma Books. p. 184. ISBN 9781929631018.

- Di Scala, Italy: From Revolution to Republic, 1700 to the Present, p. 234.

- Taylor, Blaine, Fascist Eagle: Italy's Air Marshal Italo Balbo

- Smith, Italy: A Modern History, p. 273.

- Rosario F. Esposito, La massoneria e l'Italia. Dal 1800 ai nostri giorni, Rome: Edizioni Paoline, 1979, p. 362.

- Vittorio Gnocchini, L'Italia dei Liberi Muratori. Brevi biografie di Massoni famosi, Rome-Milan: Erasmo Edizioni-Mimesis, 2005, p. 22.

- Rosario F. Esposito, La massoneria e l'Italia. Dal 1800 ai nostri giorni, Rome: Edizioni Paoline, 1979, p. 372. OCLC 979542254

- Di Scala, Italy: From Revolution to Republic, 1700 to the Present, p. 234; Smith, Italy: A Modern History, p. 365.

- Di Scala, Italy: From Revolution to Republic, 1700 to the Present, p. 234; Smith, Italy: A Modern History, p. 365.

- "Italian Air Armada Hops 800 Miles (July 14, 1933)". Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- "Balbo Pillar Recalls Flight (July 22, 1965)". Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- "Balbo Here This Afternoon (July 15, 1933)". Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- Harmer, C.H.C. (1984). Newfoundland Air Mails. Cinnaminson, NJ: American Air Mail Society. p. 159.

- "Canadian Postal Archives Database". data4.collectionscanada.ca. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- "Great Italian armada is acclaimed by millions as it wings over the city". New York Times. 20 July 1933.

- "TIME Magazine – U.S. Edition – June 26, 1933 Vol. XXI No. 26". Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- Italo Balbo comandosupremo.com

- Taylor, Fascist Eagle: Italy's Air Marshal Italo Balbo, p. 63.

- Time Life Books, World War II: Italy at War

- "General Italo Balbo, Unofficial Clarenville Webpage – Clarenville, Newfoundland". clarenville.newfoundland.ws.

- Segrè, Claudio G. Italo Balbo: a fascist life. Univ of California Press, 1990, p.280

- Kelly, Saul, The Lost Oasis, p. 102

- Gunther, John (1940). Inside Europe. Harper & Brothers. pp. 259–260.

- Time Magazine Benito in Balboland

- Sarfatti, Michelle (2006). The Jews in Mussolini's Italy: From Equality to Persecution. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 102. ISBN 0299217302. OCLC 62324746.

- Segrè, G. Claudio (1987). Italo Balbo: a Fascist Life. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 348. ISBN 9780520910690. OCLC 44960352.

- Kelly, Saul, The Lost Oasis, p. 121

- Kelly, Saul, The Lost Oasis, p. 122

- Kelly, Saul, The Lost Oasis, p. 130

- General Felice Porro, "Come fu abbattuto l'aereo di Balbo", in Rivista Aeronautica, May 1948.

- Franco Pagliano, "La morte di Balbo", in La storia illustrata nº 6, Year IX, June 1965, p. 779.

- Giorgio Rochat (1986). Italo Balbo, Edizioni Utet, p. 301.

- Giordano Bruno Guerri, Italo Balbo, Mondadori, 1998

- Folco Quilici, Tobruk 1940. Dubbi e verità sulla fine di Italo Balbo, Mondadori, 2006.

- Taylor, Fascist Eagle: Italy's Air Marshal Italo Balbo, p. 124.

- Bechthold, Mike (2017). Flying to Victory: Raymond Collishaw and the Western Desert Campaign, 1940–1941. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 42. ISBN 9780806155968.

- Trip, Gabriel (25 August 2017), "Far From Dixie, Outcry Grows Over a Wider Array of Monuments", Washington Post, retrieved 5 December 2017

- Greenfield, John. "Monument to fascist Balbo likely to remain, but aldermen could still rename street". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- Ida B. Wells Campaign, 31 May 2018, archived from the original on 22 January 2019, retrieved 22 January 2019

- Carter, Nick (May 2019), "The meaning of monuments: remembering Italo Balbo in Italy and the United States", Cambridge University Press, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 219–235, doi:10.1017/mit.2019.12, S2CID 165043240

References

- Di Scala, Spencer (2004). Italy: From Revolution to Republic, 1700 to the Present. Boulder, CO: Westview Press ISBN 0-8133-4176-0

- Kelly, Saul (2002). The Lost Oasis: The Desert War and the Hunt for Zerzura. Westview Press ISBN 0-7195-6162-0 (HC)

- Smith, Denis Mack (1959). Italy: A Modern History. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. LCCN 59-62503

- Taylor, Blaine (1996). Fascist Eagle: Italy's Air Marshal Italo Balbo. Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company ISBN 1-57510-012-6

External links

- Berselli, Aldo (1963). "BALBO, Italo". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 5: Bacca–Baratta (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ISBN 978-8-81200032-6.

- Italo Balbo and the Sioux

- Doubts raised into official story of Balbo's death

- Newspaper clippings about Italo Balbo in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW