Death and legacy of Tom Thomson

The death of Tom Thomson, the Canadian painter, occurred on 8 July 1917, on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Provincial Park in Nipissing District, Ontario, Canada. After Thomson drowned in the water, his upturned canoe was discovered later that afternoon and his body eight days later. Many theories regarding Thomson's death—including that he was murdered or committed suicide—have become popular in the years since his death, though these ideas lack any substantiation.

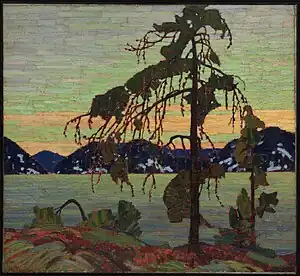

Thomson stands tall as a figure in Canadian art. His later work has had a profound influence on both the artists contemporary to him as well as those coming much later. Paintings such as The Jack Pine and The West Wind have taken a prominent place in the culture of Canada and are some of the country's most iconic pieces of art. In addition to his prominence as an artist, he has developed a reputation as an ideal Canadian outdoorsman, proficient in canoeing and fishing, though his talents in the former have come to be doubted.

Background

The outdoorsman

Though he is most known for his painting, Tom Thomson is often mythologized as a veritable outdoorsman.[1] He was taken out of school at an early age, possibly due to a lung condition.[2][3][4] This afforded him time to explore wooded areas and develop a deep appreciation for nature.[5] He spent much of his time on walks with his grandmother's first cousin, Dr. William Brodie, a well known entomologist, ornithologist and botanist.[6][7] He similarly developed a love for both fishing and hunting,[8][9] though he eventually gave up hunting after shooting a deer "as the look in its eyes was too human."[9][10]

Dr. James MacCallum contributed stories to Thomson's image as an outdoorsman, including one story that Thomson encountered a large wolf who, after sniffing him briefly, left him alone.[1] He further wrote,

[Thomson] was wont to paddle out into the centre of the lake on which he happened to be camping and spend the whole night there in order to get away from the flies and mosquitos [sic]. Motionless he studied the night skies and the changing outline of the shores while beaver and otter played around his canoe.[1][11]

Thomson has often been remembered as an expert canoeist. David Silcox has argued that this image is likely romanticized.[12] A. Y. Jackson wrote that Thomson "paddled like an Indian," holding his abilities in high esteem.[12] Despite this, Park ranger Mark Robinson said that Thomson admitted to him in 1913 that he did not know much about canoeing.[12] In addition, there are multiple stories of him capsizing.[13][14][15] In 1912, after hearing that Thomson had capsized and lost most of his supplies on a canoeing trip up the Mississagi River, friend John McRuer replied saying, "You might have been drowned you devil; and that was not the first time you were bumped, eh!"[12]

Despite these romantic images, an area that Thomson was no doubt proficient in was fishing. The deep love of fishing he developed while young remained for his entire life, so much so that his reputation through Algonquin Park was equally divided between art and angling.[16] While most who visited the Park were led by hired guides, Thomson moved through on his own. Indeed, many of his fishing locations appear in his work.[17] Upon visiting Canoe Lake for the first time in 1914, A. Y. Jackson wrote to J. E. H. MacDonald, "It appears that Tom Thomson is some fisherman, quite noted round here."[18][19][20]

1917 sketching season

From 1914 onward, Thomson regularly traveled to Algonquin Park in the spring, either camping on Canoe Lake or staying at the Mowat Lodge hotel. He spent his time there sketching and working as a fishing guide, returning to Toronto in the fall, producing larger canvas works from his original sketches.[21] In 1917 Thomson returned to Canoe Lake at the beginning of April, arriving early enough to paint the remaining snow and the ice breaking up on the surrounding lakes.[21][22] The paintings became his own visual diary of the day,[21][23] morphing into a series that he described as, "a record of the weather for 62 days, rain or shine, or snow, dark or bright."[24] He wrote home to his father saying that, though he had not sold many sketches that year, that he thought he could "get along for another year at least while I stick to painting as long as I can."[25] In his final letter to MacCallum — sent only one day before his disappearance — he complained of flies and mosquitoes. He had not done much sketching since they emerged, but was hopeful the warmer weather would soon kill them off. He promised to send along some of his winter sketches and was looking forward to sketching on several trips planned for the next two months.[26][note 1]

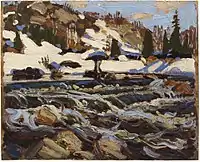

The works he completed over this spring display the masterful control of colour he had come to develop—especially apparent in a painting like The Rapids[28]—and are painted with a particular "crispness and freshness."[22] His sketches in particular show how he matured into "a subtlety of expression, using a brisk but delicate handling."[21] The bold and expressive brushstrokes that he is now famous for are evident in paintings like Path Behind Mowat Lodge and Tea Lake Dam.[29] Also on display in the former are small areas of bare wood panel, visible through the paint. This device further adds to the lighting of the scene.[30] The aggressive style of painting Thomson utilized was seen consistently in the Expressionist movement that followed his death.[31] His final works have been described by art historians David Silcox and Harold Town as moving in the direction of abstraction.[32][33][note 2] This is especially evident in what is perhaps his final work, After the Storm, which, "When viewed up close, Thomson's thick, broad application of paint in this landscape melts into pure abstraction."[34] The landscapes of his final works in late spring and early summer often contain these types of bold, generalized forms.[35]

Besides the deep love he had come to develop for Algonquin Park, Thomson was beginning to show an eagerness to depict areas beyond the park and explore other northern subjects.[36] In a May 1917 letter to his brother-in-law, he wrote:

I may possibly go out on the Canadian Northern [Railway] this summer to paint the Rockys [sic] but have not made all the arrangements yet. If I go it will be in July & August.[37][38]

A. Y. Jackson suggested Thomson would have traveled even further north, just as the other members of the Group of Seven eventually did.[39]

The Rapids, Spring 1917. Private collection, Toronto

The Rapids, Spring 1917. Private collection, Toronto Tea Lake Dam, Summer 1917. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

Tea Lake Dam, Summer 1917. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg After the Storm, Summer 1917. Private collection

After the Storm, Summer 1917. Private collection

Death

On the morning of 8 July 1917, Thomson was seen walking to Joe Lake Dam with Shannon Fraser, the owner of the Mowat Lodge.[40] He often spent his night there when the park proved too cold for camping.[36] Mark Robinson, a park ranger, noted in his diary that Thomson "left Fraser's Dock after 12:30 pm to go to Tea Lake Dam or West Lake."[40] Thomson disappeared during this canoeing trip on Canoe Lake.[41][note 3][note 4] His upturned canoe was spotted later in the afternoon, while his body was discovered in the lake eight days later on 16 July.[40][41][note 5] His watch had stopped at 12:14[35][45] and he had a four inch bruise on his right temple.[46]

The body was examined by Dr. Goldwin Howland who concluded that the official cause of death was drowning.[41][47][note 6] The coroner, Dr. Arthur E. Ranney, supported Howland's conclusion that the drowning was accidental, further writing that "the evidence from the other six witnesses points that the cause of death was drowning."[48] Regarding the four inch bruise on Thomson's temple, he wrote that, "no doubt, [it] was caused by stricking [sic] some [obstacle], like a stone, when the body was drowned."[48]

The day after the body was discovered, it was interred in Mowat Cemetery near Canoe Lake.[41][35][49][note 7] Under the direction of Thomson's older brother George, the body was exhumed two days later and was shipped to Owen Sound. It was re-interred in the family plot beside the Leith Presbyterian Church on 21 July in what is now the Municipality of Meaford.[50][51]

With financial assistance provided by MacCallum, on 27 September 1917 J. E. H. MacDonald, John William Beatty, Shannon Fraser, George Rowe and local residents erected a memorial cairn at Hayhurst Point on Canoe Lake, where Thomson died.[52][note 8] Because of Thomson's deep love for the area, the Group "had not the heart to go back to Algonquin Park, so they moved to Algoma and Lake Superior, and then to the Arctic, Yukon, Labrador, and other parts of the country."[54][55]

Legacy

"Your Canadian art apparently, for now at least, went down in Canoe Lake. Tom Thomson still stands as the Canadian painter, harsh, brilliant, brittle, uncouth, not only most Canadian but most creative. How the few things of his stick in one's mind."

—David Milne in a letter to H. O. McCurry, 1930[56][57]

Since his death, Thomson's work has grown in value and popularity. Scholar Sherrill Grace has written that Thomson is a "haunting presence" for Canadian artists and that he "embodies the Canadian artistic identity."[58] Group of Seven member Arthur Lismer similarly wrote that "Tom Thomson is the manifestation of the Canadian character."[59]

In 2002, the National Gallery of Canada staged a major exhibition of his work, giving Thomson the same level of prominence afforded Picasso, Renoir, and the Group of Seven in previous years.[60] As of 2009, the highest price achieved by a Thomson sketch was Early Spring, Canoe Lake (1917) which sold in 2009 for $2,749,500 (equivalent to C$3,403,000 in 2021). Few major canvases remain in private collections, making the record unlikely to be broken.[61] One example of the demand Thomson's work has achieved is the previously lost Sketch for Lake in Algonquin Park (1912/13). The painting was discovered in an Edmonton basement in 2018 and went on to sell for nearly half a million dollars at a Toronto auction.[62][63] The increased value of Thomson's work has led to the discovery of numerous forgeries of his work on the market.[64][65][66]

In the summer of 2004 another historical marker honouring Thomson was moved from its previous location nearer the centre of Leith to the graveyard in which Thomson is now buried. The grave site has become a popular spot for visitors to the area with many fans of Thomson's work leaving pennies or small art supplies behind as tribute.[67]

In 1967, the Tom Thomson Art Gallery opened in Owen Sound.[68] In 1968 Thomson's shack from behind the Studio Building was moved to the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg.[69] Numerous examples of his work are also on display at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario. Thomson's influence can be seen in the work of later Canadian artists, including Emily Carr, Goodridge Roberts, Harold Town, and Joyce Wieland.[70]

An "untainted" artist

In the years since his death, Thomson has often been described as being independent of previous artistic traditions.[71][72][73] Many have pointed to the fact that he never visited Europe or museums in the United States as evidence that he managed to avoid the developments of Modernist experiment.[73] Thomson's lack of formal art education similarly caused the other members of the group to later see him as a natural, untainted artist, and this view has entered the myth and public perception surrounding him.[72][74]

David Silcox and Andrew Hunter have argued that these perceptions were primarily propagated by his friends, those who formed the Group of Seven in the years following his death and others in the Canadian art scene,[note 9] nearly all of whom relied on the same basic details in their treatments of Thomson's life and career.[75] Lismer, for example, wrote, "[Thomson] had no connection with styles or schools... He had nothing to do with Europe and in his art there is not a trace of inherited style or influence from abroad... If one knew Thomson, one also realized that he knew nothing of such as things as [Art Nouveau or Impressionism]."[73] Jackson similarly wrote that Thomson's "rugged individuality was never dominated by any outside influence,"[73] and that Thomson was the "Instigator of the movement to the North Country."[76] Lawren Harris echoed these views, saying "There was nothing that interfered with Tom's direct, primal vision of nature. He was completely innocent of any of the machinery of civilization and was happiest when away from it in the north."[77] Barker Fairley wrote that, "Neither theory nor any acquired opinion can have had any permanent place in Thomson's mind. He was naïve throughout."[78] Harold Mortimer-Lamb wrote, "With his equipment he went to Nature and communed with her in all her moods."[79] Blodwen Davies wrote, "Through the story of painting in Canada there stalks a tall, lean trailsman, with his sketch box and paddle, an artist and dreamer who made the wilderness his cloister and there worshipped Nature in her secret moods."[80][81] F. B. Housser wrote, "Never before had such knowledge and the feeling for such things been given to expression in paint. Thomson's canvases are unique in the annals of all art especially when it is remembered that he was untrained as a painter. His master was nature."[82] In general, members of the Group claimed that their art did not originate in established artistic traditions but was instead dictated by the landscape itself.[71][note 10] A. Y. Jackson described Thomson as "the guide, the interpreter" who introduced his friends to "a new world, the north country."[83][84] Dennis Reid argued similarly, writing that Thomson's death was seen "almost as a sacrifice to the idea of an indigenous Canadian art... Thomson was... to become Canada's first Old Master, and as an idea he has acted as a constant inspiration to all who believed that the secret of Canada's self-knowledge is somehow contained in the land."[83][84] Revisionist art historians have criticized the view that Thomson and the Group of Seven were originators of a new Canadian nationalist style of art.[85][note 11]

Despite the popular notion that Thomson had no formal art instruction, it is possible that he briefly studied under British artist William Cruikshank around 1905.[86] Only two sources corroborate this however. The first is a single undated note from Cruikshank to professor James Mavor, arranging to bring a "Tomson" [sic] to meet him.[87][88] Further complicating the matter is that the original class list no longer survives.[88] The second is a letter from H. B. Jackson to Blodwen Davies, writing, "Tom studied from life & the antique in art school. If I remember right Cruikshank was the instructor."[89][90] Besides in-person instruction, it is also possible that he read John Ruskin's 1857 handbook, The Elements of Drawing, while learning to draw.[91] Outside of these possibilities, it seems that he had no other art instruction.[92] Thomson's work in commercial art however did seem to have an influence on his painting, leading him to familiarity with the Art Nouveau as well as Arts and Crafts movements.[3][93] Similarly, working with his fellow artists caused him to become aware of the techniques of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.[94][95] Regarding Art Nouveau tendencies, Jackson wrote that, "We (the Group of Seven and Tom Thomson) treated our subjects with the freedom of designers. We tried to emphasize colour, line and pattern."[96] These techniques can be seen within Thomson's work, whether it be Impressionism in The Pointers (1916–17); Art Nouveau in Northern River (1914–15), Decorative Landscape, Birches (1915–16), Spring Ice (1915–16) and The West Wind (1916–17); or Expressionism in After the Storm (1917) and Cranberry Marsh (1916).[97]

Popular culture and other honours

Cedar and jagged fir

uplift sharp barbs

against the gray

and cloud-piled sky;

and in the bay

blown spume and windrift

and thin, bitter spray

snap

at the whirling sky;

and the pine trees

lean one way.

A wild duck calls

to her mate,

and the ragged

and passionate tones

stagger and fall,

and recover,

and stagger and fall,

on these stones—

are lost

in the lapping of water

on smooth, flat stones.

This is a beauty

of dissonance,

this resonance

of stony strand,

this smoky cry

curled over a black pine

like a broken

and wind-battered branch

when the wind

bends the tops of the pines

and curdles the sky

from the north.

This is the beauty

of strength

broken by strength

and still strong.

A. J. M. Smith, 1926

Canadian poet and member of the Montreal Group, A. J. M. Smith wrote in a letter to Sandra Djwa that it was Thomson's painting The Jack Pine that helped him get started on his poem, "The Lonely Land."[99][100] The poem, perhaps Smith's most known and most anthologized, was first published in The McGill Fortnightly Review on 9 January 1926, subtitled "Group of Seven."[99][101] It underwent several revisions, appearing in Canadian Forum in July 1927 and the American magazine The Dial in June 1929.[102] Smith had not seen the painting in person, but only as a colour reproduction.[99][100] The first stanza utilizes the texture ("jagged," "smooth") and rhythmic movement ("sharp," "bitter," "barbs") of a painting as it describes a northern landscape.[103] Smith's 1925 poem "Prayer" proceeds similarly, even referencing a jack pine in one of the early stanzas.[104] Several other books of poetry inspired by Thomson have also been published, including George Whipple's Tom Thomson and Other Poems (2000),[105] Troy Jollimore's Tom Thomson in Purgatory (2006),[106] and Kevin Irie's Viewing Tom Thomson: A Minority Report (2012).[107]

Joyce Wieland's 1976 film The Far Shore is based on the life and death of Tom Thomson.[108] Journalist Roy MacGregor's 1980 novel Shorelines—later reissued in 2002 as Canoe Lake—is a fictional interpretation of Thomson's death.[109] Neil Lehto's 2005 book Algonquin Elegy is a self-described piece of historical fiction, focusing on Thomson's death.[110] Several songs reference Thomson's death, including The Tragically Hip's 1991 single "Three Pistols."[111]

In 2018, a section of Ontario Highway 60—the primary corridor through Algonquin Park—was renamed "Tom Thomson Parkway."[112] Canada Post has issued multiple stamps of Thomson's work from as early as 1967. Works depicted have included The Jack Pine (printed in 1967), April in Algonquin Park (1977), Autumn Birches (1977), The West Wind (1990) and In the Northland (2016).[113]

Alternative theories

Many alternative theories have swirled around the nature of Tom Thomson's death, including that he was murdered or committed suicide. Though these ideas lack substantiation, they have continued to persist in the popular culture.[41][114][115] Andrew Hunter has pointed to Robinson as being largely responsible for the suggestion that there was more to Thomson's death than accidental drowning. Hunter expanded on this thought, writing, "... I am convinced that people's desire to believe the Thomson murder mystery/soap opera is rooted in the firmly fixed idea that he was an expert woodsman, intimate with nature. Such figures aren't supposed to die by 'accident'. If they do, it is like Grey Owl's being exposed as an Englishman."[116]

In 1935, Blodwen Davies published the first exploration of Thomson's death outside of newspaper accounts from the time of Thomson's death.[117] A self-published edition of 500 copies, her doubts about the official decision of cause of death sold poorly.[118] In 1970, Judge William Little's book, The Tom Thomson Mystery, recounted how in 1956 Little and three friends dug up Thomson's original gravesite in Mowat Cemetery on Canoe Lake.[119] They believed that the remains they found were Thomson's. In the fall of 1956, medical investigators determined that the body was that of an unidentified Aboriginal.[120] Canadian newspaper columnist Roy MacGregor has described his 2009 examination of records of the 1956 remains unearthed by William Little (the remains have been reburied or lost) and concluded that the body was actually Thomson's, indicating "that Thomson never left Canoe Lake."[121]

Debunking

David Silcox and Harold Town have pointed out incorrect evidence being used to justify the belief that Thomson was murdered. Chief among these is that Thomson's feet were found tangled in wire. This claim is a misinterpretation of Robinson's 1930s observation that the body had a carefully bound fishing line around a sprained ankle, actually a common remedy for arthritis or a sore joint.[41] Silcox has proposed that it is easy to imagine Thomson standing in his canoe to cast a fishing line, losing his balance in the process, hitting his head on the gunwale and falling into the water unconscious, only to drown.[41]

In an essay titled "The Many Deaths of Tom Thomson," published in 2011, Gregory Klages describes how testimony and theories regarding Thomson's death have evolved since 1917.[114] Assessing the secondary accounts against the primary evidence, Klages concludes that Thomson's death is consistent with the official assessment of an accidental drowning. Historians Kathleen Garay and Christl Verduyn state, "Klages' forensic archival sleuthing does provide for the first time some degree of certainty regarding this event."[122] Klages expanded on these ideas in a book with a similar name, The Many Deaths of Tom Thomson: Separating Fact from Fiction, published in 2016. He particularly challenges MacGregor's claims, suggesting MacGregor is guilty of misrepresenting evidence.[115]

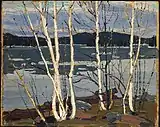

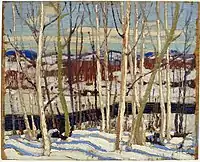

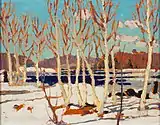

Selection of Thomson's final sketches

Thomson produced roughly three dozen sketches in his final spring. His landscapes illustrate several snowy scenes in Algonquin Park and indicate an increasing fascination in birch trees.

Early Spring, Spring 1917. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Early Spring, Spring 1917. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto Canoe Lake, Spring 1917. Private collection, Calgary

Canoe Lake, Spring 1917. Private collection, Calgary Early Spring, Canoe Lake, Spring 1917. Private collection, Toronto

Early Spring, Canoe Lake, Spring 1917. Private collection, Toronto Ice Covered Lake, Spring 1917. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound

Ice Covered Lake, Spring 1917. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound

Birches, Spring 1917. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound

Birches, Spring 1917. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound Spring in Algonquin Park, Spring 1917. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

Spring in Algonquin Park, Spring 1917. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg Open Water, Joe Creek, Spring 1917. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Open Water, Joe Creek, Spring 1917. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto April in Algonquin Park, Spring 1917. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound

April in Algonquin Park, Spring 1917. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound

Woods in Winter, Spring 1917. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound

Woods in Winter, Spring 1917. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound Spring Break-up, Spring 1917. Private collection, Montreal

Spring Break-up, Spring 1917. Private collection, Montreal Spring Flood, Spring 1917. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

Spring Flood, Spring 1917. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg Lowery Dickson's Cabin, Spring 1917. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Lowery Dickson's Cabin, Spring 1917. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Northern Lights, Spring 1917. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Northern Lights, Spring 1917. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa Northern Lights, Spring 1917. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Northern Lights, Spring 1917. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto Dark Waters, Spring 1917. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Dark Waters, Spring 1917. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa Spring, Spring 1917. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Spring, Spring 1917. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

References

Footnotes

- Mowat P. O., July 7, 1917

Dear Sir:

I am still around Frasers and have not done any sketching since the flies started. The weather has been wet and cold all spring and the flies and mosquitos much worse than I have seen them any year and the fly dope doesnt [sic] have any effect on them. This however is the second warm day we have had this year and another day or so like this will finish them. Will send my winter sketches down in a day or two and have every intention of making some more but it has been almost impossible lately. Have done a great deal of paddling this spring and the fishing has been fine. Have done some guiding for fishing parties and will have some other trips this month and next with probably sketching in between. [...]

Hoping you are well, I am

Yours truly / Tom Thomson[26][27] - For more regarding Thomson's later abstract tendencies, refer to:

- On 10 July, Fraser sent a telegram to MacCallum, writing:

DR MCCALLUM [sic] BLULER (Bloor) ST TORONTO ONT TOMES [sic] CANOE FOUND UPSIDE DOWN NO TRACE OF TOM SUNCE [sic] SUNDAY NOON J S FRASER[42]

- A popular—if unverifiable—story recounts that he was attempting to catch a particularly large bass on Joe Lake the day he disappeared.[43]

- The telegram from J.S. Fraser to Tom's brother John read simply:

Canoe Lake Ont July 16–17 J Thomson Owen Sound.

- Found tom [sic] this morning.

- Howland later recounted the following:

I saw body of man floating in Canoe Lake Monday, July 16th, at about 10 A. M. and notified Mr. George Rowe a resident who removed body to shore. On 17th Tuesday, I examined [the body] and found it to be that of a man aged about 40 years in advanced stage of decomposition, face abdomen and limbs swollen, blisters on limbs, was a bruise on right temple size of 4" long, no other sign of external marks visible on body, air issuing from mouth, some bleeding from right ear, cause of death drowning.[47]

- Mowat Cemetery was located at 45°33′47″N 78°43′42″W.

- MacDonald wrote to Thomson's father,

I have just returned from Canoe Lake where I spent the weekend helping Mr. [J. W.] Beatty to put on the plate and give the cairn a few finishing touches. The cairn is a fine piece of work, and with the brass plate in position it looks quite imposing. It stands on a prominent point in Canoe Lake right at the head of the lake facing north and can be seen from all directions. It is situated near an old favorite camping spot of Tom's. [...] The result goes a long way to beautifying the tragedy of Tom's death.[53]

- Hunter has pointed to F. B. Housser, Newton McTavish, Albert H. Robson, Barker Fairley, Harold Mortimer-Lamb and Dr. James MacCallum as being major influences in propagating the Thomson legends.[75]

- For example, see:

- Harris (1929), p. 185

- Jackson (1958), p. 22

- For example, see:

- Dawn (2007)

- Jessup (2007)

- McKay (2011), Ch. 8–9

Citations

- Silcox & Town (2017), p. 236.

- Silcox & Town (2017), p. 41.

- Hill (2002), p. 113.

- MacDonald (1917b), p. 47.

- Silcox (2015), p. 4.

- Murray (1999), pp. 6–7.

- Wadland (2002), p. 93.

- Hunter (2002), pp. 28–29.

- Murray (2015), "Prologue".

- Henry (1931).

- MacCallum (1918), p. 382.

- Silcox & Town (2017), p. 237.

- Silcox (2015), p. 15.

- Silcox & Town (2017), pp. 215, 237.

- Wadland (2002), pp. 94–95.

- Hunter (2002), pp. 28, 28n39.

- Hunter (2002), p. 29.

- Hunter (2002), p. 28.

- Hill (2002), p. 123.

- Jackson (1914).

- Murray (2015), "From the Studio Building to Algonquin Park and Home Again".

- Hill (2002), p. 141.

- Robinson (1930), p. 3.

- Murray (1999), p. 116.

- Murray (2002a), pp. 303–04.

- Thomson (1917b).

- Murray (2002a), p. 306.

- Silcox (2015), p. 17.

- Silcox (2015), pp. 17–18.

- Silcox (2015), pp. 74–75.

- Silcox (2015), p. 73.

- Silcox (2015), pp. 17–18, 44, 52, 57, 62, 68, 73.

- Silcox & Town (2017), p. 148.

- Silcox (2015), p. 52.

- Hill (2002), p. 142.

- Silcox (2015), p. 18.

- Thomson (1917a).

- Murray (2002a), pp. 304–05.

- Murray (1999), p. 122.

- Murray (2002b), p. 317.

- Silcox & Town (2017), p. 49.

- Fraser (1917a).

- Hunter (2002), p. 28n39.

- Fraser (1917b).

- Thomson (1934).

- Murray (1999), p. 23.

- Howland (1917).

- Ranney (1931).

- Robinson (1917).

-

- Hill (2002), p. 142

- Murray (2002b), p. 317

- Silcox & Town (2017), p. 49–50

- "Historic Leith Church". www.meaford.ca. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

-

- Hill (2002), p. 142

- Murray (2002b), p. 317

- Silcox (2006), p. 213

- Silcox & Town (2017), p. 240

- MacDonald (1917a).

- Roza (1997), p. 31.

- Jackson (1919), p. 5.

- Milne (1930).

- Dejardin (2018), pp. 17, 194.

- Grace (2004), p. 96.

- Lismer (1934), pp. 163–64.

- Reid (2002a).

- Silcox (2015), p. 66.

- Vikander (2018).

- The Canadian Press (2018).

- Silcox & Town (2017), p. 182.

- Silcox (2015), p. 74.

- Dellandrea (2017).

- "Leith United Church | Heritage Meaford". www.heritagemeaford.com. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- "Tom Thomson Art Gallery". City of Owen Sound. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- Dexter (1968).

- Stanners (2017).

- Silcox (2006), p. 29–30, 212.

- Roza (1997), pp. 29–30.

- Silcox & Town (2017), p. 85.

- Silcox (2006), p. 29–30.

- Hunter (2002), p. 35.

- Jackson (1935).

- McInnes (1944).

- Fairley (1920), p. 246.

- Mortimer-Lamb (1919), p. 124.

- Hunter (2002), p. 36.

- Davies (1930).

- Housser (1926).

- Roza (1997), p. 30n29.

- Reid (1971), p. 90.

- Silcox (2015), p. 58.

-

- Murray (1986), p. 6

- Reid (2002b), p. 70

- Silcox & Town (2017), p. 43

- Stacey (2002), p. 52

- Cruikshank.

- Reid (2002b), p. 70n21.

- Jackson (1931).

- Hill (2002), p. 113n18.

- Murray (1999), p. 2.

- Silcox (2015), p. 9.

- Reid (2002b), pp. 65–83.

- Roza (1997), p. 30n29.

- Silcox & Town (2017), p. 88.

- McKay (2011), p. 185.

- Silcox (2015), p. 68, 71.

- Silcox (2006), p. 214.

- Roza (1997), p. 74.

- Djwa (1992), p. 208.

- Smith (2006), p. 53n1.

- Roza (1997), pp. 75–76.

- Roza (1997), pp. 74–75.

- Roza (1997), pp. 67–68.

- Whipple (2000).

- Jollimore (2006).

- Irie (2012).

- Wieland (1976).

- MacGregor (1980).

- Lehto (2005).

- Silcox (2015), p. 65.

- Cilliers (2018).

- "Search Canadian Stamps - Canada - Tom Thomson". www.canadianpostagestamps.ca. Canadian Stamps. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- Klages (2011), pp. 274–97.

- Klages (2016).

- Hunter (2002), p. 39.

- Davies (1935), pp. 122–25.

- Davies (1935).

- Little (1970), pp. 110–127.

- Sharpe (1956).

- MacGregor (2010).

- Verduyn (2011), p. 7.

Sources

Primary sources

- Cruikshank, William. "to Prof. Mavor, no year" (14 February) [Letter]. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, Series: James Mavor Papers, Box: 4a. Toronto: University of Toronto.

- Davies, Blodwen. "Application for the exhumation of the body of one Thos. Thomson drowned in Canoe Lake in 1917" (27 July 1931). Attorney General Central Registry Criminal and Civil Files, Fonds: Blodwen Davies fond, File: 2225, ID: RG 4-32. North York: Archives of Ontario.

- Fraser, J.S. "Telegram to Dr. James MacCallum" (10 July 1917a) [Telegram]. Dr. James M. MacCallum Papers. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada Archives.

- ———. "Telegram to John Thomson" (16 July 1917b) [Telegram]. Tom Thomson Collection, File: 1.3, ID: MG30-D284. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada.

- Harris, Lawren (1929). "Creative Art and Canada". In Brooker, Bertram (ed.). Yearbook of the Arts in Canada, 1928–1929. Toronto: Macmillan Company of Canada. pp. 177–86.

- Henry, Louise. "to Blodwen Davies" (11 March 1931) [Letter]. Blodwen Davies collection, Fonds: Blodwen Davies, Box: 11, ID: MG30-D38. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada.

- Howland, Gordon W. "Copy of Dr. G. W. Howland's affidavit (Originals withdrawn from circulation. Copies available on microfilm C-4579)" (17 July 1917). 11, Fonds: Blodwen Davies fond, ID: MG30-D38. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada.

- Jackson, A. Y. "A. Y. Jackson to J. E. H. MacDonald" (14 February 1914) [Letter]. J. E. H. MacDonald collection, Fonds: MacDonald fonds, Box: 11, ID: MG30-D111. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada.

- ——— (1919). Foreword. Catalogue of an Exhibition of Paintings by the Late Tom Thomson, 1–21 March 1919. By Arts Club of Montreal.

- ——— (1935). Foreword. A Study of Tom Thomson: The Story of a Man Who Looked for Beauty and for Truth in the Wilderness. By Davies, Blodwen. Toronto: Discus Press.

- ——— (1958). A Painter's Country. Toronto: Clarke Irwin.

- Jackson, H. B. "H. B. Jackson to Blodwen Davies" (29 April 1931) [Letter]. Blodwen Davies collection, Fonds: Blodwen Davies fond, Box: 11, ID: MG30-D38. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada.

- Lismer, Arthur (January 1934). "The West Wind". McMaster Monthly. 43 (4): 163–64.

- MacCallum, James (31 March 1918). "Tom Thomson: Painter of the North". Canadian Magazine. pp. 375–85.

- MacDonald, J. E. H. (3 October 1917a). "Memorial cairn". Letter to John Thomson.

- MacDonald, J. E. H. (November 1917b). "Landmark of Canadian Art". Rebel. 2 (2).

- Milne, David (April 1930). "draft, in Milne family papers". Letter to H.O. McCurry.

- Ranney, A. E. "Letter to Blodwen Davies (Original withdrawn from circulation. Copies available on microfilm C-4579)" (7 May 1931). 11, Fonds: Blodwen Davies, ID: MG30-D38. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada.

- Robinson, Mark. "Mark Robinson's Daily journal" (16–18 July 1917) [Journal entry]. Addison family, Fonds: Addison family fonds, ID: 97-011. Peterborough: Trent University Archives.

- ——— (23 March 1930). "Tom Thomson". Letter to Blodwen Davies.

- Sharpe, Noble (1956). "Dr. Noble Sharpe, Re: Human Bones received from unmarked grave in Algonquin Park, Oct. 30, 1956". Centre for Forensic Sciences, Toronto. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- Thomson, George. "to Blodwen Davies" (23 April 1934) [Letter]. Blodwen Davies collection, Fonds: Blodwen Davies, Box: 11, ID: MG30-D38. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada.

- Thomson, Tom. "Tom Harkness" (23 April 1917a) [Letter]. Tom Thomson papers, ID: MG30-D284. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada Archives.

- Thomson, Tom. "James MacCallum" (7 July 1917b) [Letter]. Dr. James M. MacCallum papers. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada Archives.

Secondary sources

- Canadian Press, The (30 May 2018). "Tom Thomson sketch discovered in Edmonton basement sells for $481K at auction". thestar.com. Toronto Star. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- Cilliers, Roland (19 September 2018). "Section of Highway 60 officially becomes Tom Thomson Parkway". MuskokaRegion.com. Huntsville Forester. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- Davies, Blodwen (1930). Paddle & Palette: The Story of Tom Thomson. Toronto: Ryerson Press.

- ——— (1935). A Study of Tom Thomson: The Story of a Man Who Looked for Beauty and for Truth in the Wilderness. Toronto: Discuss Press.

- Dawn, Leslie (2007). "The Britishness of Canadian Art". In O'Brian, John; White, Peter (eds.). Beyond Wilderness: The Group of Seven, Canadian Identity, and Contemporary Art. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Dejardin, Ian A. C. (2018). "Dazzle and Kick: The Life of David Milne". In Milroy, Sarah; Dejardin, Ian A. C. (eds.). David Milne: Modern Painting. London: Philip Wilson Publishers. pp. 17–28. ISBN 978-1781300619.

- Dellandrea, Jon S. (July–August 2017). "Brush with Infamy". Literary Review Canada. Vol. 26, no. 6. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- Dexter, Gail (1 June 1968). "Tom Thomson's dollar-a-month shack becomes a Group of Seven shrine". Toronto Star.

- Djwa, Sandra (1992). "Who is This Man Smith?: Second and Third Thoughts on Canadian Modernism". In New, W. H. (ed.). Inside the Poem: Essays and Poems in Honour of Donald Stephens. Toronto: Oxford Press. pp. 205–15.

- Fairley, Barker (March 1920). "Tom Thomson and Others". The Rebel. 3 (6): 244–48.

- Grace, Sherril (2004). Inventing Tom Thomson: From Biographical Fictions to Fictional Autobiographies and Reproductions. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Hill, Charles (2002). "Tom Thomson, Painter". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre. pp. 111–143.

- Housser, F. B. (1926). A Canadian Art Movement: The Story of the Group of Seven. Toronto: Macmillan.

- Hunter, Andrew (2002). "Mapping Tom". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto/Ottawa: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 19–46.

- Irie, Kevin (2012). Viewing Tom Thomson: A Minority Report. Calgary: Frontenac House. ISBN 978-1897181638.

- Jessup, Lynda (2007). "Art for a Nation". In O'Brian, John; White, Peter (eds.). Beyond Wilderness: The Group of Seven, Canadian Identity, and Contemporary Art. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Jollimore, Troy (2006). Tom Thomson in Purgatory. Chesterfield: Margie Inc. ISBN 978-0971904057.

- Klages, Gregory (2011). "The Many Deaths of Tom Thomson". In Verduyn, Christl; Garay, Kathy (eds.). Archives & Canadian Narratives. Black Point, NS: Fernwood. pp. 274–297.

- ——— (2016). The Many Deaths of Tom Thomson: Separating Fact from Fiction. Toronto: Dundurn. ISBN 978-1459731967. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- Lehto, Neil J. (2005). Algonquin Elegy Tom Thomson's Last Spring. New York: Universe Inc. ISBN 978-0595361328.

- Little, William T. (1970). The Tom Thomson Mystery. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson Ltd.

- MacGregor, Roy (1980). Shorelines: a Novel. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. ISBN 978-0771054594.

- ——— (2010). Northern Light: The Enduring Mystery of Tom Thomson and the Woman Who Loved Him. Toronto: Random House Canada. ISBN 978-0307357397.

- McInnes, Graham (Director) (1944). West Wind (35mm film, colour). National Film Board of Canada.

- McKay, Marylin J. (2011). Picturing the Land: Narrating Territories in Canadian Landscape Art, 1500–1950. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Mortimer-Lamb, Harold (29 March 1919). "Letter to the editor, with attached draft article". Studio Magazine.

- Murray, Joan (1986). The Best of Tom Thomson. Edmonton: Hurtig.

- ——— (1999). Tom Thomson: Trees. Toronto: McArthur & Co. ISBN 978-1552780923.

- ——— (2002a). "Tom Thomson's Letters". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto/Ottawa: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 297–306.

- ——— (2002b). "Chronology". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto/Ottawa: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 307–317.

- ——— (2015). "Thomson-Algonquin / Algonquin-Thomson". tomthomsoncatalogue.org. Tom Thomson Catalogue. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Reid, Dennis (1971). A Bibliography of the Group of Seven. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada.

- ———, ed. (2002a). Tom Thomson. Toronto/Ottawa: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada.

- ——— (2002b). "Tom Thomson and the Arts and Crafts Movement in Toronto". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto/Ottawa: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 65–83.

- Roza, Alexandra M. (1997). Towards a Modern Canadian Art 1910–1936: The Group of Seven, A.J.M. Smith and F.R. Scott (PDF) (Thesis). McGill University.

- Silcox, David P. (2006). The Group of Seven and Tom Thomson. Richmond Hill: Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55407-154-8.

- ——— (2015). Tom Thomson: Life and Work. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. ISBN 978-1487100759.

- ———; Town, Harold (2017). The Silence and the Storm (Revised, Expanded ed.). Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. ISBN 978-1443442343.

- Smith, A. J. M. (2006). Gnarowski, Michael (ed.). Selected Writings. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1550026658.

- Stacey, Robert (2002). "Tom Thomson as Applied Artist". In Reid, Dennis; Hill, Charles C. (eds.). Tom Thomson. Toronto/Ottawa: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 47–63.

- Stanners, Sarah (2017). Passion Over Reason: Tom Thomson & Joyce Wieland. Kleinburg: McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

- Verduyn, Christl (2011). Garay, Kathleen (ed.). Archival Narratives for Canada: Re-telling Stories in a Changing Landscape. Winnipeg: Fernwood Pub. ISBN 978-1552664469.

- Vikander, Tessa (9 May 2018). "Tom Thomson sketch heads to Toronto auction block after languishing in Edmonton basement". thestar.com. Toronto Star. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- Wadland, John (2002). "Tom Thomson's Places". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre. pp. 85–109.

- Whipple, George (2000). Tom Thomson and other poems (1st ed.). Manotick: Penumbra Press. ISBN 978-1894131117.

- Wieland, Joyce (Director) (1976). The Far Shore (35mm film, colour). Toronto: Far Shore Inc.

External links

- Death on a Painted Lake: The Tom Thomson Tragedy, a website with a collection of archival information

- The Lonely Land, a 1926 poem by A. J. M. Smith directly inspired by Thomson's painting The Jack Pine