Decapoda

The Decapoda or decapods (literally "ten-footed") are an order of crustaceans within the class Malacostraca, including many familiar groups, including crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp, and prawns. Most decapods are scavengers. The order is estimated to contain nearly 15,000 extant species in around 2,700 genera, with around 3,300 fossil species.[1] Nearly half of these species are crabs, with the shrimp (about 3,000 species) and Anomura including hermit crabs, porcelain crabs, squat lobsters (about 2500 species) making up the bulk of the remainder.[1] The earliest fossils of the group date to the Devonian.

| Decapoda Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

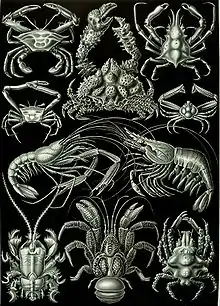

| From left to right: Grapsus grapsus (Brachyura), Coconut crab (Anomura), Lysmata amboinensis (Caridea), Homarus gammarus (Astacidea). | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Superorder: | Eucarida |

| Order: | Decapoda Latreille, 1802 |

| Suborders | |

|

Dendrobranchiata | |

Anatomy

Decapods can have as many as 38 appendages,[2] arranged in one pair per body segment. As the name Decapoda (from the Greek δέκα, deca-, "ten", and πούς / ποδός, -pod, "foot") implies, ten of these appendages are considered legs. They are the pereiopods, found on the last five thoracic segments.[2] In many decapods, one pair of these "legs" has enlarged pincers, called chelae, with the legs being called chelipeds. In front of the pereiopods are three pairs of maxillipeds that function as feeding appendages. The head has five pairs of appendages, including mouthparts, antennae, and antennules. There are five more pairs of appendages on the abdomen. They are called pleopods. There is one final pair called uropods, which, with the telson, form the tail fan.[2]

Evolution

A 2019 molecular clock analysis suggested decapods originated in the Late Ordovician around 455 million years ago, with the Dendrobranchiata (prawns) being the first group to diverge. The remaining group, called Pleocyemata, then diverged between the swimming shrimp groupings and the crawling/walking group called Reptantia, consisting of lobsters and crabs. High species diversification can be traced to the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, which coincides with the rise and spread of modern coral reefs, a key habitat for the decapods.[3] Despite the inferred early origin, the oldest fossils of the group such as Palaeopalaemon only date to the Late Devonian.[4]

The cladogram below shows the internal relationships of Decapoda, from analysis by Wolfe et al. (2019).[3]

| Decapoda |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the cladogram above, the clade Glypheidea is excluded due to lack of sufficient DNA evidence, but is likely the sister clade to Polychelida, within Reptantia.[3]

Classification

Classification within the order Decapoda depends on the structure of the gills and legs, and the way in which the larvae develop, giving rise to two suborders: Dendrobranchiata and Pleocyemata. The Dendrobranchiata consist of prawns, including many species colloquially referred to as "shrimp", such as the "white shrimp", Litopenaeus setiferus. The Pleocyemata include the remaining groups, including "true shrimp".[5] Those groups that usually walk rather than swim (Pleocyemata, excluding Stenopodidea and Caridea) form a clade called Reptantia.[6]

This classification to the level of superfamilies follows De Grave et al.[1]

Order Decapoda Latreille, 1802

- Suborder Dendrobranchiata Bate, 1888

- Penaeoidea Rafinesque, 1815

- Sergestoidea Dana, 1852

- Suborder Pleocyemata Burkenroad, 1963

- Infraorder Stenopodidea Bate, 1888

- Infraorder Caridea Dana, 1852

- Procaridoidea Chace & Manning, 1972

- Galatheacaridoidea Vereshchaka, 1997

- Pasiphaeoidea Dana, 1852

- Oplophoroidea Dana, 1852

- Atyoidea De Haan, 1849

- Bresilioidea Calman, 1896

- Nematocarcinoidea Smith, 1884

- Psalidopodoidea Wood-....., 1874

- Stylodactyloidea Bate, 1888

- Campylonotoidea Sollaud, 1913

- Palaemonoidea Rafinesque, 1815

- Alpheoidea Rafinesque, 1815

- Processoidea Ortmann, 1896

- Pandaloidea Haworth, 1825

- Physetocaridoidea Chace, 1940

- Crangonoidea Haworth, 1825

- Infraorder Astacidea Latreille, 1802

- Enoplometopoidea de Saint Laurent, 1988

- Nephropoidea Dana, 1852

- Astacoidea Latreille, 1802

- Parastacoidea Huxley, 1879

- Infraorder Glypheidea Winckler, 1882

- Glypheoidea Winckler, 1882

- Infraorder Axiidea de Saint Laurent, 1979b

- Infraorder Gebiidea de Saint Laurent, 1979

- Infraorder Achelata Scholtz & Richter, 1995

- Infraorder Polychelida Scholtz & Richter, 1995

- Infraorder Anomura MacLeay, 1838

- Aegloidea Dana, 1852

- Galatheoidea Samouelle, 1819

- Hippoidea Latreille, 1825a

- Chirostyloidea Ortmann, 1892

- Lithodoidea Samouelle, 1819

- Lomisoidea Bouvier, 1895

- Paguroidea Latreille, 1802

- Infraorder Brachyura Linnaeus, 1758

- Section Dromiacea De Haan, 1833

- Dromioidea De Haan, 1833

- Homolodromioidea Alcock, 1900

- Homoloidea De Haan, 1839

- Section Raninoida De Haan, 1839

- Section Cyclodorippoida Ortmann, 1892

- Section Eubrachyura de Saint Laurent, 1980

- Subsection Heterotremata Guinot, 1977

- Aethroidea Dana, 1851

- Bellioidea Dana, 1852

- Bythograeoidea Williams, 1980

- Calappoidea De Haan, 1833

- Cancroidea Latreille, 1802

- Carpilioidea Ortmann, 1893

- Cheiragonoidea Ortmann, 1893

- Corystoidea Samouelle, 1819

- Dairoidea Serène, 1965

- Dorippoidea MacLeay, 1838

- Eriphioidea MacLeay, 1838

- Gecarcinucoidea Rathbun, 1904

- Goneplacoidea MacLeay, 1838

- Hexapodoidea Miers, 1886

- Leucosioidea Samouelle, 1819

- Majoidea Samouelle, 1819

- Orithyioidea Dana, 1852c

- Palicoidea Bouvier, 1898

- Parthenopoidea MacLeay,

- Pilumnoidea Samouelle, 1819

- Portunoidea Rafinesque, 1815

- Potamoidea Ortmann, 1896

- Pseudothelphusoidea Ortmann, 1893

- Pseudozioidea Alcock, 1898

- Retroplumoidea Gill, 1894

- Trapezioidea Miers, 1886

- Trichodactyloidea H. Milne-Edwards, 1853

- Xanthoidea MacLeay, 1838

- Subsection Thoracotremata Guinot, 1977

- Cryptochiroidea Paul'son, 1875

- Grapsoidea MacLeay, 1838

- Ocypodoidea Rafinesque, 1815

- Pinnotheroidea De Haan, 1833

- Subsection Heterotremata Guinot, 1977

- Section Dromiacea De Haan, 1833

References

- Sammy De Grave; N. Dean Pentcheff; Shane T. Ahyong; et al. (2009). "A classification of living and fossil genera of decapod crustaceans" (PDF). Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. Suppl. 21: 1–109. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-06.

- "Decapoda characters and anatomy". University of Bristol: Decapoda characters. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- Wolfe, Joanna M.; Breinholt, Jesse W.; Crandall, Keith A.; Lemmon, Alan R.; Lemmon, Emily Moriarty; Timm, Laura E.; et al. (24 April 2019). "A phylogenomic framework, evolutionary timeline, and genomic resources for comparative studies of decapod crustaceans". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 286 (1901). doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.0079. PMC 6501934. PMID 31014217.

- Gueriau, Pierre; Rak, Štěpán; Broda, Krzysztof; Kumpan, Tomáš; Viktorýn, Tomáš; Valach, Petr; Zatoń, Michał; Charbonnier, Sylvain; Luque, Javier (2020-10-25). "Exceptional Late Devonian arthropods document the origin of decapod crustaceans". doi:10.1101/2020.10.23.352971. S2CID 226229304.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Elena Mente (2008). Reproductive Biology of Crustaceans: Case Studies of Decapod Crustaceans. Science Publishers. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-57808-529-3.

- G. Scholtz; S. Richter (1995). "Phylogenetic systematics of the reptantian Decapoda (Crustacea, Malacostraca)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 113 (3): 289–328. doi:10.1006/zjls.1995.0011.

External links

Data related to Decapoda at Wikispecies

Data related to Decapoda at Wikispecies- Decapod Crustacea "Tree of Life" page at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

- Decapoda at Curlie