Dedham, Massachusetts in the American Revolution

The town of Dedham, Massachusetts, participated in the American Revolutionary War and the protests and actions that led up to it in a number of ways. The town protested the Stamp Act and then celebrated its repeal by erecting the Pillar of Liberty. Townsmen joined in the boycott of British goods following the Townshend Acts, and they supported the Boston Tea Party. Dedham's Woodward Tavern was the site where the Suffolk Resolves gathering was first convened.

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Dedham |

|---|

|

| Main article |

| Dedham, Massachusetts |

| By year |

| By topic |

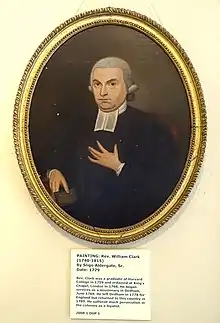

At the outset of the war, nearly every man in town went off when the alarm was sounded following the Battles of Lexington and Concord. There were several Tories in the community, notably Rev. William Clark, but they were largely ostracized and even arrested for being traitors. Many soldiers passed through the town during the war, including George Washington. There was also an encampment of French troops under the command of Count Rochambeau.

In May 1776, several months before Congress acted, Town Meeting voted that "if the Honourable Congress should, for the safety of the Colonies, declare their independence of the Kingdom of Great Britain, they, the said Inhabitants, will solemnly engage with their lives and fortunes to support them in the measure."

Prelude to war

Stamp Act and the Pillar of Liberty

When Parliament imposed the Stamp Act 1765 on the 13 colonies, there was little effect in Dedham and thus little outcry.[1] The one person most affected was Dr. Nathaniel Ames who would have to pay for each sheet of paper used in his almanac, his liquor license, and for his medical papers.[1] He began stirring up his fellow townsmen, and Town Meeting appointed a committee to draft a set of instructions to Samuel Dexter, their representative in the Great and General Court.[1] Seven men were appointed to the committee, but their draft was likely written by Ames.[2] The letter, which instructed Dexter to oppose the Act, was unanimously approved on October 21, 1765.[1]

When the act was repealed, there was great rejoicing in Boston but just an "illumination" at the Ames Tavern.[3] Some of those celebrating included the Sons of Liberty, whose Dedham Chapter included Nathaniel Ames, Ebenezer Battelle, Abijah Draper, and Dr. John Sprague, as well as the Free Brothers, a similar group which included Ames, Battelle, Sam West, Manasseh Cutler, Nat Fisher, and Joseph Ellis Jr.[3]

On July 22, 1766, Nathaniel Ames and the Sons of Liberty erected the Pillar of Liberty on the church green at the Corner of High and Court streets.[4] A "vast concourse of people" attended its erection.[4] All that was there on that date as a block of granite from Battelle's farm that had been squared, polished, and had an inscription written by Ames.[4] It is the only monument known to have been erected by the Sons of Liberty.

Seven months later, a 10' pillar was added with a bust of William Pitt the Elder.[4] Pitt was credited, according to the inscription on the base, of having "saved America from impending slavery, and confirmed our most loyal affection to King George III by procuring a repeal of the Stamp Act."[4] The bust was carved by Skilling, a Boston craftsman best known producing figureheads for ships.[4] The monument was destroyed on the night of May 11, 1769.[5]

In inscription stated on the base's north face:

The Pillar of Liberty

To the Honor of William Pitt Esqr

& other Patriots who saved

America from impending slavery

and confirmed our most loyal Affections

to King George III by pro

curing the repeal of the Stamp Act

18th March 1766

[4]

And on its west face:

The Pillar of Liberty

Erected by the Sons of Liberty

in this Vicinity

Laus DEO REGI et Immunitatm

autoribusq. maxine Patrono

Pitt, qui Rempub. rurfum evulfit

Faucibus Orci.

[Praise to God, the King, and the

exceptional work of Pitt, the great-

est benefactor, who plucked the

republic from the jaws of Hell.

[4]

On December 1, 1766, Town Meeting voted to condemn the mob action in Boston that destroyed property.[6] It also voted, as an act of thanks for repealing the Stamp Act, that those who suffered should be compensated by the province.[6]

Townshend Acts

After Parliament adopted the Townshend Acts, Town Meeting voted on November 16, 1767, to join in the boycott of imported goods:[7][8]

...that as this Town will in all prudent methods encourage the use of such articles as may be produced in the British American Colonies, particularly in this Province, and discourage the use of superfluities, imported from abroad, and will not purchase any article of foreign produce or manufacture of said Colonies.[7]

On March 5, 1770, the same day Parliament voted to repeal the act, Town Meeting that "we will not directly or indirectly have any commerce or dealing with those few traders... who have had so little regard to the good of their country" as to oppose the boycott.[9] It also voted that "we will not make use of any foreign tea, nor allow the consumption of it in our respective families."[9]

Boston Tea Party and the Intolerable Acts

Eleven days after the Sons of Liberty dumped tea into Boston Harbor, Town Meeting gathered to "highly approve" the actions taken by the mob and to create a Committee of Correspondence to keep in touch with other communities.[10] They also voted that

...as so many political evils have been brought about by an unreasonable liking to the use of tea, and as we are convinced that it us baneful to the human constitution, we will do all in our power to prevent the use of it in time to come; and if any shall refuse to comply...we shall consider them as unfriendly to the liberties of the people, as well as giving flagrant proof of their own stupidity under a most grievous oppression.[10]

Parliament responded by passing the Intolerable Acts which, among other things, banned town meetings unless they were approved in advance by the governor.[10] Dedham held five illegal town meetings despite the Act.[11] At these meetings, they supported the Suffolk Resolves, the Continental Congress, the Continental Association, and acts to further embarrass anyone in Dedham caught drinking tea.[12] This included publishing the names of anyone "so devoid of patriotism" to drink tea as a traitor.[8]

There was a great risk in doing so, as Dedham was so close to Boston and the troops amassed there under General Thomas Gage.[13] The troops frequently went out marching and were often spotted on roads in Dedham and surrounding towns.[13]

Suffolk Resolves

A general convention of delegates from every town in Suffolk County was called for August 16, 1774, at Doty's Tavern in Stoughton (today Canton).[11] The group agreed on the need to take a united stand against the Intolerable Acts but, since not every community was represented, it was decided to adjourn and try again to get every community represented.[11] Richard Woodward, a member of the Committee of Correspondence, offered to host the next gathering on September 6, 1774.[11] Woodword and Nathaniel Sumner were elected as delegates from Dedham.[14]

The Woodward Tavern at the corner of Ames and High Streets, where the Norfolk County Registry of Deeds sits today. When the more than 60 delegates gathered, they determined that such a large group made it impossible to accomplish their goals.[11] Instead, the group unanimously agreed on the need to oppose the British reprisals and then appointed a subcommittee draft a resolution.[11] Three days later, at the home of Daniel Vose in Milton, the Suffolk Resolves were adopted.[11]

The resolves were then rushed by Paul Revere to the First Continental Congress. The Congress in turn adopted as a precursor to the Declaration of Independence. The resolves denounced the Intolerable Acts as "gross infractions of those rights to which we are justly entitled by the laws of nature, the British constitution, and the charter of the province" and called on the towns to organize militias to protect "the rights of the people."[15] In 1774, the year after the Boston Tea Party, the Town outlawed India tea and appointed a committee to publish the names of any resident caught drinking it.[16]

Eliphalet Pond incident

In May 1774, Eliphalet Pond signed a letter with several other addressed to Governor Thomas Hutchinson that was, in the opinion of many in Dedham, too effusive in praise given the actions the British crown had recently taken on the colonies.[17] A group confronted him the day after the Powder Alarm.[17] What happened next is unclear. According to Pond's own account, he spoke calmly with the group and they were satisfied that he was a patriot.[17] In other accounts, he and his black servant, Jack, had to hold off a mob by pointing muskets out the second story window.[17]

Raising of militia company

On October 18, 1774, the first parish met to choose military officers.[13] There was a "long debate" about whether the Town should raise a militia company at the January 1775 town meeting but, unable to come to a consensus, the matter was deferred until March.[18] A company of 60 minutemen was established on March 6 and bound to serve for nine months.[18]

Revolutionary War

Battles at Lexington and Concord

On the morning of April 19, 1775, a messenger came "down the Needham road" with news about the battle in Lexington.[5][18] He stopped at the home of Samuel Dexter and ran up to the front door.[18] Dexter met him at the front door and, upon hearing the news, nearly fainted.[18] He had to be helped back into his house.[18]

Church bells were rung and signal guns were fired to alert the minutemen and militia of the need to gather.[20] Captain Joseph Guild's company began leaving in small groups, as soon as enough men to form a platoon had assembled.[20] When "a croaker" claimed that it was a false alarm, Guild had him gagged and left under guard so that he could not dissuade any faint hearted men from heading off to the battle.[20][5]

Within an hour of the first notice, the "men of Dedham, even the old men, received their minister's blessing and went forth, in such numbers that scarce one male between sixteen and seventy was left at home."[21][22] A total of 89 men from the first parish went off, led by Captains Aaron Fuller and George Guild.[23] Captain William Bullard led 59 from the second parish, and Daniel Draper and William Ellis led 55 men from the third parish.[23] From the Springfield parish, David Fairbanks and Ebenezer Battle led 80.[23] By the end of the day, even the older veterans from the French and Indian War headed off to Lexington.[23] It total, there were four companies plus minutemen.[22]

Aaron Guild, a captain in the British Army during the French and Indian War, was plowing his fields in South Dedham (today Norwood) when he heard of the battle.[24] He immediately "left plough in furrow [and] oxen standing" to set forth for the conflict, arriving in time to fire upon the retreating British.[24] The companies led by Bullard, Draper, Ellis, Fairbanks, and Joseph Guild also took aim at the retreating redcoats.[23] They, along with units from Needham and Lynn, took up positions behind a wall and along a hill near the Jason Russell house in Menotomy.[23] They waited along the south side of the road for the British to retreat.[23] A British flanking company surprised them, pushed them back towards Russell's house, and killed 10 men, including Dedham's Elias Haven from Battle's company.[25] Dr. Nathaniel Ames tended to the wounded.[25]

Of the more than 300 men who responded to the Lexington alarm, some were only gone from home for a few hours while others stayed with the army for up to 13 days.[25] Battle's company walked the entire length of the battle, collecting weapons and burying the dead.[25]

Faith Huntington

Faith Huntington and several friends arrived in Roxbury to visit her brother, a soldier in the Continental Army, on June 17, 1775. Instead of a glamorous and exciting military display, they witnessed the brutality of the Battle of Bunker Hill. The realization that this might be the fate of her brothers and husband seems to have been too much for Huntington, and she began experiencing episodes of serious depression. As these bouts grew worse, and as her husband Jedediah, who was in Boston, did not feel he could leave his men, he and his mother brought Huntington to stay with friends in Dedham, where he could visit her frequently.[26] There, she was treated for depression by Dr. John Sprague.

On November 24, 1775, shortly after one of these visits, she hanged herself.[27] Her funeral was held at the Samuel Dexter House on November 28, 1775 and she was buried in the tomb of Nathaniel Ames.[27] Following the funeral, the mourners went to the Ames Tavern.[27]

Dedham soldiers

The Town voted to hire an additional 120 minutemen on May 29, 1775.[20] They were called into action just a few weeks later, but only 17 ended up fighting at the Battle of Bunker Hill.[20] There, they lined up between the breastwork and the rail fence.[20]

After the war moved south, the Continental Army issued the town a quota but, as the town had already run through its available men, it was forced to hire mercenaries from Boston.[28][20][29] The population at the time was between 1,500 and 2,000 persons, of which 672 men fought in the Revolution and 47 did not return.[30]

General George Washington gave Timothy Stowe[lower-alpha 1] a commission in the army as a captain during the war, and Stowe led a company to Fort Ticonderoga.[31]

Other troops

Following the outbreak of hostilities, military traffic from throughout southern and western New England was "marching thick" through Dedham on their way to Boston.[20] It was good for Dedham taverns and farmers who suddenly had a lot more customers, but it also brought disease.[20] The town suffered through waves of dysentery and smallpox.[20]

During the Revolution, the corner of modern-day Washington and Worthington Streets was the site of an encampment for French troops under the command of Count Rochambeau.[33][34] A monument to the soldiers stands at the corner of Marsh and Court streets.[35]

Tories

In 1770, Rev. William Clark of the Anglican St. Paul's Church commented with disdain on the republican sensibilities of Dedhamites.[36] He found their notions of liberty to be more akin to licentiousness, and asked to be transferred to congregations in Georgetown, Maine or Annapolis, Nova Scotia, but was refused by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.[37] As his territory stretched into Stoughton, he attempted to move there but the Dedham Selectmen declared him to be a non-resident and cut off his salary from the taxes his parishioners paid.[38]

In April 1776, the General Court ordered him to be arrested as a Tory, but he was never brought into custody.[38] The people of Dedham stoned his church and then took it over for use as a military storehouse.[39][38] From then on, Clark would secretly conduct services in his house.[39]

By March 1777, Clark announced that he would cease preaching; such an action was easier to swallow than eliminating prayers for the king.[38][39] On May 19, 1777, he was charged by the Board of Selectmen in Dedham of being a traitor to the American Revolution.[40][41] Samuel White, Tim Richards Jr., and Daniel Webb were all charged with the same offense.[40]

Two days later, on May 21, he was surrounded by a mob as he went home, but "escaped on my parole."[38] The mob was upset that he had provided a letter of recommendation to a loyalist whom they had previously run out of town after stealing his farming utensils and other property.[42][39]

Clark was arrested on June 5, 1777, and held for a day at the Woodward Tavern in a room with a picture of Oliver Cromwell.[43] After being denied bail, he was brought to Boston to stand before a military tribunal.[44][43] When his carriage broke, he was forced to walk several miles the rest of the way.[43] His trial, he said, "was carried on in so near a resemblance to the Romish Inquisition."[43] He was denied counsel and was not told what the evidence against him was.[43][45]

Clark was nearly found not guilty, as the only thing he had done was to provide aide to a fellow man in distress.[39] He refused to pledge allegiance to the Commonwealth, however, and so was sent onto a prison ship for 10 weeks.[43][45] While there, his health suffered greatly.[39][43] He was released on a £500 bond and prohibited from traveling more than one mile from his house.[43] In June 1778, Fisher Ames obtained a pass for him and Clark was allowed to leave America.[43][46]

Town Meeting supported independence

In May 1776, Town Meeting voted that "if the Honourable Congress should, for the safety of the Colonies, declare their independence of the Kingdom of Great Britain, they, the said Inhabitants, will solemnly engage with their lives and fortunes to support them in the measure."[47]

Notable visitors

George Washington

Following the evacuation of Boston General George Washington spent the night of April 4, 1776, at Samuel Dexter's home on his way to New York.[27][48] Dexter had retired to Connecticut, but his fellow Governor's Councilor Joshua Henshaw was living at the house.[20][27]

Adams family

During the revolution, Samuel Adams returned to Massachusetts for a two month break from the Continental Congress.[49] He found his home on Purchase Street in Boston had been destroyed.[49] The windowpanes were etched with insults and caricatures were drawn on the walls.[49] His garden was trampled, the outbuildings knocked down, and the house was robbed of all its furnishings.[49] Adams was unable to fix the house, so he moved his family to Dedham.[49]

In July 1775, Abigail Adams came to visit Sam Adams' wife, Betsy, and found her "comfortably situated, in a little Country cottage with patience, perseverance and fortitude for her companions, and in better Health than she has enjoyed for many months past."[50][51] The family later moved back to Boston.[52] Abigail also attended the First Church and Parish in Dedham to hear Jason Haven preach.[51]

On January 9, 1777, John Adams stayed at the home of Dr. John Sprague as he rode to Baltimore to attend the Second Continental Congress.[53]

Notes

References

- Hanson 1976, p. 140.

- Hanson 1976, p. 140-141.

- Hanson 1976, p. 141.

- Hanson 1976, p. 142.

- Abbott 1903, pp. 290–297.

- Hanson 1976, p. 142-143.

- Hanson 1976, p. 143.

- Warren 1931, p. 35.

- Hanson 1976, p. 146.

- Hanson 1976, p. 148.

- Hanson 1976, p. 149.

- Hanson 1976, p. 149-150.

- Hanson 1976, p. 150.

- Rudd 1908, p. 15.

- Suffolk County Convention (1774). "Suffolk Resolves". Constitution Society. Retrieved November 27, 2006.

- Smith, Frank (July 4, 2007). "The Genealogical History of Dover, Massachusetts". Lazy Acres North. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007.

- Hanson 1976, p. 151.

- Hanson 1976, p. 152.

- Peter Schworm (October 1, 2006). "He was a patriot, not a redcoat". The Boston Globe. Retrieved November 27, 2006.

- Hanson 1976, p. 155.

- Bancroft, George (1912). History of the United States of America, from the Discovery of the Continent [to 1789]. D. Appleton. p. 164. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- Worthington 1869, p. 26.

- Hanson 1976, p. 153.

- From the Aaron Guild Memorial Stone, dedicated in 1903, which stands outside the Norwood public library and reads: "Near this spot/ Capt. Aaron Guild/ On April 19, 1775/ left plow in furrow, oxen standing/ and departing for Lexington/ arrived in time to fire upon/ the retreating British."

- Hanson 1976, p. 154.

- "General Huntington - Valley Forge National Historical Park". www.nps.gov. US National Park Service. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Warren 1931, p. 39.

- "A Capsule History of Dedham". Dedham Historical Society. 2006. Archived from the original on October 6, 2006. Retrieved November 10, 2006.

- Hanson 1976, p. 158-159.

- Rev. Elias Nason (1890). "A Gazetteer of the State of Massachusetts". Cape Cod History. Retrieved December 10, 2006.

- Clarke 1903, p. 1.

- Clarke 1903, p. 3.

- "Daniel Slattery's house and the Temperance Hall". The Dedham Times. August 8, 1995. p. 6.

- "First mass in Dedham, 1843, celebrated in Slattery home". The Boston Globe. September 29, 1923. p. 3. Retrieved September 20, 2019.

- Parr 2009, p. 108.

- Hanson 1976, p. 156.

- Hanson 1976, p. 156-157.

- Hanson 1976, p. 157.

- Worthington 1827, p. 70.

- Hanson 1976, p. 155-156.

- Dedham Historical Society 2001, p. 27.

- Hanson 1976, p. 157-158.

- Hanson 1976, p. 158.

- Worthington 1827, p. 70-71.

- Worthington 1827, p. 71.

- Hurd 1884, p. 56.

- Hanson 1976, p. 159.

- Guide Book To New England Travel. 1919.

- Schiff 2022, p. 308.

- Schiff 2022.

- Adams, Abigail (July 25, 1775). "Letter from Abigail Adams to John Adams, 25 July 1775". Massachusetts Historical Society. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- Schiff 2022, p. 318.

- Adams, John (July 25, 1775). "Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, 9 January 1777". Massachusetts Historical Society. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

Works cited

- Abbott, Katharine M. (1903). Old Paths And Legends Of New England (PDF). New York: The Knickerbocker Press. pp. 290–297. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- Clarke, Wm. Horatio (1903). Mid-Century Memories of Dedham. Dedham Historical Society.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Dedham Historical Society (2001). Images of America:Dedham. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-0944-0. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- Hanson, Robert Brand (1976). Dedham, Massachusetts, 1635-1890. Dedham Historical Society.

- Hurd, Duane Hamilton (1884). History of Norfolk County, Massachusetts: With Biographical Sketches of Many of Its Pioneers and Prominent Men. J. W. Lewis & Company. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- Parr, James L. (2009). Dedham: Historic and Heroic Tales From Shiretown. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-59629-750-0.

- Rudd, Edward Huntting (1908). Dedham's Ancient Landmarks and Their National Significance. Dedham Transcript Printing and Publishing Company.

- Schiff, Stacy (2022). The Revolutionary: Samuel Adams. Little, Brown & Co. ISBN 9780316441117.

- Warren, Charles (1931). Jacobin and Junto: Or, Early American Politics as Viewed in the Diary of Dr. Nathaniel Ames, 1758-1822. Harvard University Press.

- Worthington, Erastus (1827). The history of Dedham: from the beginning of its settlement, in September 1635, to May 1827. Dutton and Wentworth. Retrieved November 8, 2019.

- Worthington, Erastus (1869). Dedication of the Memorial Hall, in Dedham, September 29, 1868: With an Appendix. John Cox Jr. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.