Dehua porcelain

Dehua porcelain (Chinese: 德化陶瓷; pinyin: Déhuà Táocí; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tek-hòe hûi), more traditionally known in the West as Blanc de Chine (French for "White from China"), is a type of white Chinese porcelain, made at Dehua in the Fujian province. It has been produced from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) to the present day. Large quantities arrived in Europe as Chinese export porcelain in the early 18th century and it was copied at Meissen and elsewhere. It was also exported to Japan in large quantities. In 2021, the kilns of Dehua were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List along with many other sites near Quanzhou for their importance for medieval maritime trade and the exchange of cultures and ideas around the world.[1]

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

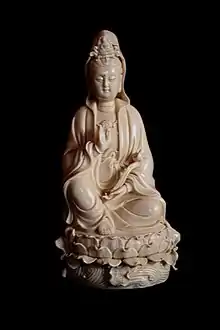

Dehua porcelain statue of Guanyin, Ming Dynasty | |

| Location | China |

| Part of | Quanzhou: Emporium of the World in Song-Yuan China |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iv) |

| Reference | 1561 |

| Inscription | 2021 (44th Session) |

History

The area along the Fujian coast was traditionally one of the main ceramic exporting centers. Over one-hundred and eighty kiln sites have been identified extending in historical range from the Song period to present. The two principal kiln sites were those of Qudougong (屈斗宫) and Wanpinglun (碗坪仑). The Wanpinglun site is the older of the two and manufactured pressed wares and others. The kilns of Dehua also produced other ceramic wares, including some with under glaze blue decoration.

From the Ming period porcelain objects were manufactured that achieved a fusion of glaze and body traditionally referred to as "ivory white" and "milk white." The special characteristic of Dehua porcelain is the very small amount of iron oxide in it, allowing it to be fired in an oxidising atmosphere to a warm white or pale ivory color. This color makes it instantly recognizable and quite different from the porcelain from the Imperial kilns of Jingdezhen, which contains more iron and has to be fired in reduction (i.e., an atmosphere with carbon monoxide) if it is not to appear an unpleasant straw color.[2]

The unfired porcelain body is not very plastic but vessel forms have been made from it. Donnelly lists the following types of product: figures, boxes, vases and jars, cups and bowls, fishes, lamps, cup-stands, censers and flowerpots, animals, brush holders, wine and teapots, Buddhist and Taoist figures, secular figures and puppets. There was a large output of figures, especially religious figures, e.g., Guanyin, Maitreya, Luohan and Ta-mo figures. Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy, was particularly revered in Fujian and there exist innumerable figures of her. Donnelly says, “There is no doubt that figures constitute the great glory of blanc de Chine.” Some have been produced with little modification from the late 16th or early 17th century.[3] Crisply modeled figures with a smooth white glaze were popular as were joss-stick holders, brush pots, Dogs of Fo, libation cups and boxes.

The devotional objects produced at Dehua (incense burners, candlesticks, flower vases and statuettes of saints) “conformed to the official stipulations of the early Ming period, not only in their whiteness but also in imitating the shape of archaic ritual objects”.[4] They were probably used in the domestic shrines that every Chinese home possessed. However, one Confucian polemicist, Wen Zhenheng (1585–1645), specifically forbade the use of Dehua wares for religious purposes, presumably for their lack of antiquity: “Among the censers the use of which should be specifically forbidden are those recently made in the kilns of Fujian (Dehua).”[4]

The numerous Dehua porcelain factories today make figures and tableware in modern styles. During the Cultural Revolution “Dehua artisans applied their very best skills to produce immaculate statuettes of the Great Leader and the heroes of the revolution. Portraits of the stars of the new proletarian opera in their most famous roles were produced on a truly massive scale.”[4] Mao Zedong figures later fell out of favor but have been revived for foreign collectors.

Precise dating of blanc de Chine of the Ming and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties is often difficult because the conservatism of the Dehua potters led them to produce similar pieces for decades or even for centuries. There are blanc de Chine figures being made in Dehua today (e.g. the popular Guanyin and Maitreya figures) little different from those made in the Ming dynasty.

Notable artists in blanc de Chine, such as the late Ming period He Chaozong, signed their creations with their seals. Wares include crisply modeled figures, cups, bowls and joss stick-holders.

In Japan

Many of the best examples of blanc de Chine can also be found in Japan where they are used in family altars (butsudan) and other funerary and religious uses. In Japan the white variety was termed hakuji, hakugorai or "Korean white", a term often found in tea ceremony circles. The British Museum in London has a large number of blanc de Chine pieces, having received the entire collection of P.J.Donnelly as a gift in 1980.[5]

Dehua white porcelain was traditionally known in Japan as hakugorai or “Korean White Ware.” Although Korai was a term for an ancient Korean kingdom, the term also functioned as a ubiquitous term for various products from the Korean peninsula.

The Japanese knew of the existence of the Fujian province kilns and their porcelain, now known as Dehua or Blanc de Chine ware. The Dehua kilns are located in Fujian province opposite the island of Taiwan. Coastal Fujian province was traditionally a trade center for the Chinese economy with its many ports and urban centers. Fujian white ware was meant for export to all of maritime Asia.

However a large quantity of these ceramics was intended for a Japanese market, before drastic trade restrictions by the mid 17th century. Items were largely Buddhist images and ritual utensils utilized for family altar use. An association with funerals and the dead has perhaps led to a disinterest in this ware among present day Japanese, despite a strong interest in other aspects of Chinese ceramic culture and history.

The very plain white incense tripods and associated objects for Japanese religious and ritual observance are also likely designed specifically for a Japanese market, as are the Buddhist Goddesses of Mercy with child figurines that closely resemble the Christian Madonna and Child. Such figurines were known as Maria Kannon or “Blessed Virgin Goddesses of Mercy” and were part of the “hidden Christian” culture of Tokugawa Japan which had strictly banned the religion.

White porcelain Buddhist statuary was extensively produced in Japan at the Hirado kilns and elsewhere. The two wares can be easily distinguished. Japanese figures are usually closed on the base and a small hole for ventilation can be seen. Hirado Ware also displays a slightly orange tinge on unglazed areas.

Gallery

Guanyin Bodhisattva made by He Chaozong, a famed 17th-century artist from the Ming dynasty who fashioned mainly Buddhist white porcelain statuary in the tradition of the Dehua kilns in Fujian province.

Guanyin Bodhisattva made by He Chaozong, a famed 17th-century artist from the Ming dynasty who fashioned mainly Buddhist white porcelain statuary in the tradition of the Dehua kilns in Fujian province. Ascetic Buddha from late Ming dynasty

Ascetic Buddha from late Ming dynasty A decorated cup from late Ming dynasty

A decorated cup from late Ming dynasty A white teapot from Dehua, ca. 1690-1720. The base is inscribed with the name of the Emperor Xuande, who reigned from 1426 to 1435, more than 250 years before the teapot was made. The use of earlier reign marks has a long history in China, much to the vexation of modern researchers, and was intended to indicate respect rather than to deceive. The teapot's bold geometric design anticipates the forms of European modernism by more than two centuries.

A white teapot from Dehua, ca. 1690-1720. The base is inscribed with the name of the Emperor Xuande, who reigned from 1426 to 1435, more than 250 years before the teapot was made. The use of earlier reign marks has a long history in China, much to the vexation of modern researchers, and was intended to indicate respect rather than to deceive. The teapot's bold geometric design anticipates the forms of European modernism by more than two centuries. A cup made at Meissen Porcelain Manufactory, Germany, ca. 1725-1730. Although long-known in China, the technique of making true or hard-paste porcelain was not rediscovered in Europe until J. F. Böttger's experiments at Meissen in the early 18th century. This little porcelain cup with its applied prunus or plum blossom decoration reflects the influence of a Chinese, "Blanc de Chine" porcelain prototype.

A cup made at Meissen Porcelain Manufactory, Germany, ca. 1725-1730. Although long-known in China, the technique of making true or hard-paste porcelain was not rediscovered in Europe until J. F. Böttger's experiments at Meissen in the early 18th century. This little porcelain cup with its applied prunus or plum blossom decoration reflects the influence of a Chinese, "Blanc de Chine" porcelain prototype._Blanc_de_Chine_(5175943649).jpg.webp) A modern Blanc de Chine teapot design

A modern Blanc de Chine teapot design

See also

Notes

- "Quanzhou: Emporium of the World in Song-Yuan China". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 22 Aug 2021.

- Wood, N., Chinese Glazes: Their Chemistry, Origins and Re-creation, A & C Black, London, and University of Pennsylvania Press, USA, 2007

- Donnelly, P.J., Blanc de Chine, Faber and Faber, London, 1969

- Ayers, J. and Bingling, Y., Blanc de Chine: Divine Images in Porcelain, China Institute, New York, 2002

- Harrison-Hall, J., Ming Ceramics in the British Museum, British Museum, London, 2001

References

- Ayers, J and Kerr, R., (2000), Blanc de Chine Porcelain from Dehua, Art Media Resources Ltd., google books

- Moujian, S., (1986) An Encyclopedia of Chinese Art, p. 292.

- Shanghai Art Museum, Fujian Ceramics and Porcelain, Chinese Ceramics, vol. 27, Kyoto, 1983.

- Kato Tokoku, Genshoku toki daijiten (A Dictionary of Ceramics in Color), Tokyo, 1972, p. 777.

External links

- A Handbook of Chinese Ceramics from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- https://www.britannica.com/art/Dehua-porcelain

.jpg.webp)