Demographics of Generation Alpha

Generation Alpha is a social cohort born between the early 2010s and mid 2020s. The birth years of Generation Alpha have seen a decline in birth rates, especially in the developed world.

Global trends

As of 2015, there were some two and a half million people born every week around the globe; Generation Alpha is expected to reach close to two billion by 2025.[1] For comparison, the United Nations estimated that the human population was about 7.8 billion in 2020, up from 2.5 billion in 1950. Roughly three-quarters of all people reside in Africa and Asia in 2020.[2] In fact, most human population growth comes from these two continents, as nations in Europe and the Americas tend to have too few children to replace themselves.[3]

.jpg.webp)

2018 was the first time when the number of people above 65 years of age (705 million) exceeded those between the ages of zero and four (680 million). If current trends continue, the ratio between these two age groups will top two by 2050.[4] In fact, about half of all countries had sub-replacement fertility in the mid-2010s. The global average fertility rate in 1950 was 4.7 but dropped to 2.4 in 2017. However, this average masks the huge variation between countries. Niger has the world's highest fertility rate at 7.1 while Cyprus has one of the lowest at 1.0. In general, the more developed countries, including much of Europe, the United States, South Korea, and Australia, tend to have lower fertility rates.[5] People in such places tend to have children later and fewer of them.[4] However, surveys conducted in developed economies suggest that women's desired family sizes tend to be higher than their completed fertility. Stagnant wages and eroding welfare programs are the contributing factors. While some countries, such as Sweden and Singapore, have tried various incentives to raise their fertility rates, such policies have not been particularly successful. Moreover, birth rates following the COVID-19 global pandemic might drop significantly due to economic recession.[6] As a matter of fact, data from late 2020 and early 2021 suggests that despite hopes of a baby boom due to the lockdowns, precisely the opposite happened, at least in developed nations like France or the United States, but not necessarily developing ones, such as Brazil or Uganda.[7][8][9]

Education is in fact one of the most important determinants of fertility. The more educated a woman is, the later she tends to have children, and fewer of them.[3] At the same time, the global average life expectancy has gone from 52 in 1960 to 72 in 2017.[4] Higher interest in education brings about an environment in which mortality rates fall, which in turn, increases population density. All these factors reduce fertility, as does cultural transmission.[10] Increasing immigration is problematic while policies that encourage people to have more children rarely succeed. Moreover, immigration is not an option at the global level.[5]

Half of the human population lived in urban areas in 2007, and this figure became 55% in 2019. If the current trend continues, it will reach two thirds by the middle of the century. A direct consequence of urbanization is falling fertility. In rural areas, children can be considered an asset, that is, additional labor. But in the cities, children are a burden. Moreover, urban women demand greater autonomy and exercise more control over their fertility.[11] The United Nations estimated in mid-2019 that the human population will reach about 9.7 billion by 2050, a downward revision from an older projection to account for the fact that fertility has been falling faster than previously thought in the developing world. The global annual rate of growth has been declining steadily since the late twentieth century, dropping to about one percent in 2019.[12] In fact, by the late 2010s, 83 of the world's countries had sub-replacement fertility.[13]

During the early to mid-2010s, more babies were born to Christian mothers than to those of any other religion in the world, reflecting the fact that Christianity remained the most popular religion in existence. However, it was the Muslims who had a faster rate of growth. About 33% of the world's babies were born to Christians who made up 31% of the global population between 2010 and 2015, compared to 31% to Muslims, whose share of the human population was 24%. During the same period, the religiously unaffiliated (including atheists and agnostics) made up 16% of the population but gave birth to only 10% of the world's children.[14]

Africa

.jpg.webp)

Egypt's population reached the 100-million milestone in February 2020. According to government figures, during the 1990s and 2000s, Egypt's fertility rate fell from 5.2 down to 3.0, but then rose up to 3.5 in 2018, according to the United Nations. If the current rate of growth continues, Egypt will be home to more than 128 million people by 2030. Such rapid population growth is a cause for concern in a country marked by poverty, unemployment, shortages of clean water, lack of affordable housing, and traffic congestion. Harsh geography exacerbates the problem: 95% of the population lives on just 4% of the land, a region in the neighborhood of the Nile River roughly half the size of Ireland. Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi claimed that overpopulation posed as much a threat to national security as terrorism. He launched a campaign called “Two Is Enough” in order to curb the problem, but to no avail. Egypt's fertility rate surged at around the Arab Spring, likely as a result of political chaos, economic uncertainty, and funds for birth control from Western governments drying up. Fertility rates remained the highest in rural areas, where children are considered a blessing, but the impact is most visible in Greater Cairo, a megalopolis home to over 20 million people. In general, Egypt's densely populated cities and towns have one million additional residents each year between 2008 and 2018.[15]

Nigeria was experiencing a population boom in the 2010s and is on track to become the world's third most populous nation by century's end, according to United Nations figures. However, this demographic trend comes with its own risks, namely environmental, health, and food security problems. Moreover, the nation is already battling deadly infectious diseases, which spread more easily with higher population densities, such as HIV/AIDS, malaria, and Lassa fever.[16]

Statistical projections from the United Nations in 2019 suggest that, by 2020, the people of Niger would have a median age of 15.2, Mali 16.3, Chad 16.6, Somalia, Uganda, and Angola all 16.7, the Democratic Republic of the Congo 17.0, Burundi 17.3, Mozambique and Zambia both 17.6. (This means that more than half of their populations were born in the first two decades of the twenty-first century.)[17] Benin, Burundi, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Malawi, Nigeria, Tanzania, Zambia, Yemen, and Timor-Leste had a median age of 17 in 2017, according to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluations, University of Washington.[18] These are the world's youngest countries by median age. While a booming population can induce substantial economic growth, if healthcare, education, and economic needs were not met, there would be chronic youth unemployment, low productivity, and social unrest. Investing in human capital is crucial.[17] Curbing population growth could help Africa take advantage of the demographic dividend that enabled the Asian Tigers to develop so rapidly during the late twentieth century. Africa's population boom could have a significant international impact, as many of its natives seek to migrate to other countries both within and outside Africa seeking a better life.[16]

While Africa is the world's most fertile region, it also has the world's highest child mortality rates.[4] Nevertheless, Africa is largely responsible for human population growth in the twenty-first century, overtaking Asia.[12] Moreover, sub-Saharan Africa is the only major region that is an exception to the general trend of falling family size seen around the world.[13]

Asia

East Asia

.jpg.webp)

In 2016, the People's Republic of China replaced one-child policy with the two-child policy; the nation's birth rate briefly surged before continuing on a downward path. In 2019, 14.65 million babies were born in China, the lowest since 1961. Although demographers and economists have urged the Chinese Central Government to eliminate all birth restrictions, they have been reluctant to do so. Economist Ren Zeping of Evergrande calculated that between 2013 and 2028, the number of Chinese women between the ages of 20 and 35 would drop by 30%. Official data is often unreliable and even self-contradictory. "China's birth numbers are very sloppy and highly influenced by politics," demographer Yi Fuxian of the University of Wisconsin – Madison told the South China Morning Post. Overall, China's population grew to 1.4 billion in 2019 from 1.39 billion the year before.[19] In a 2019 paper, Yi Fuxian estimated that China's average annual fertility rate was 1.18 between 2010 and 2018.[20] Less than 6% of China's population was under five years old in 2018, compared to 3.85% in Japan.[4] A Chinese person born in the late 2010s has a life expectancy of 76 years, up from 44 in 1960. According to a projection by the United Nations, China's median age would reach that of the United States in 2020 and would subsequently converge with Europe's but would remain below that of Japan. If the current trend continues, by 2050, the median age of China will be 50, compared to 42 for the United States and 38 for India.[21]

Such a trend has fueled predictions of dreadful socioeconomic problems.[22] A study by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) published in January 2020 predicts that China's population would peak in 2029 at 1.44 billion, after which decline would be "unstoppable." CASS calculated that China's population will fall to 1.36 billion by mid-century, losing almost 200 million workers. CASS recommended that the government implement policies that would address the problems of a shrinking labor force and an increasing elderly population, which means a growing dependency rate.[23] A large and young labor force and domestic consumption have driven China's rapid economic growth. Yet due to a shrinking pool of young people, China has suffered from labor shortages and reduced growth in the 2010s. Young Chinese women living in the twenty-first century tend to be reluctant to have children for a number of reasons. In large cities, such as Shanghai, people typically spend at least a third of their income on raising a child. Chinese women have become a lot more career-oriented. On top of that, Chinese workplaces generally do not offer accommodations for women with young children, who often face demotion or even unemployment after returning from maternity leave.[24] Not only do shortages of young workers have implications for China's economic prospects, they also pose a serious burden on young people being born today. They will have to take care of four grandparents and two parents on their own, as their siblings will not have been born.[25]

.jpg.webp)

As a result of cultural ideals, government policy, and modern medicine, there have been severe gender imbalances in China and India. According to the United Nations, in 2018, China and India had a combined 50 million of excess males under the age of 20. Such a discrepancy fuels loneliness epidemics, human trafficking (from elsewhere in Asia, such as Cambodia and Vietnam), and prostitution, among other societal problems.[26]

Japan at present has one of the oldest populations in the world and persistently sub-replacement fertility, currently 1.4 children per woman. Japan's population peaked in 2017.[27] In South Korea, a baby boom occurred in the aftermath of the Korean War, and the government subsequently encouraged people to have no more than two children per couple. As a result, South Korea's fertility has been falling ever since.[28] South Korea's fertility rate dropped below 1.0 in 2018 for the first time since the country began keeping statistics in 1970. The figure for 2017 was also a record low, at 1.05. Since 2005, the government has spent a fortune on child subsidies and campaigns promoting reproduction, but has had little success. Possible reasons for Korea's low fertility rate include the high cost of raising a child, high youth unemployment, the burden of childcare on career-minded women, a stressful education system, and high levels of competition in Korean society. In South Korea, because marriage is usually associated with child-rearing, it is extremely rare for children to be born out of wedlock. That figure stood at 1.9% as of 2017. By contrast, in some other developed countries, such as France and Norway, it is not uncommon for children to be born to unmarried couples, at 55% or higher.[29] Government figures show that the average age at first marriage for women climbed from 24.8 in 1990 to 30.2 in 2018 while the age of first birth was 31.6. According to Statistics Korea, women who give birth to their first child in their early 30s are unlikely to have more than one. In Korea's traditionalist society, new mothers face discrimination in the work force, and as such delaying childbirth becomes commonplace. Such a low fertility rate endangers the nation's welfare programs (including healthcare and pensions), and causes more and more schools to close. It also has implications for national security, as the South Korean military relies on conscription to confront North Korean threats.[28]

.jpg.webp)

According to the National Development Council of Taiwan (NDC), the nation's population could start shrinking by 2022 and the number of people of working age could fall by 10% by 2027. About half of Taiwanese would be aged 50 or over by 2034.[30] According to the NDC, Taiwan reached the stage of being an aging society—one in which the number of people aged 65 and above is about 7%—in 1993. Like South Korea, Taiwan has since moved from being an aging society to an aged one, where the number of elderly people exceeds 14% of the total population. It therefore took the country 25 years to make this demographic transition, compared to 17 years in South Korea. During the 2010s, Taiwan's fertility rate hovered just above 1.0, making it one of the lowest in the world.[31][32] In fact, data from the Ministry of the Interior shows the fertility rate has consistently been below 1.5 since 2001.[32] (In 2010, Taiwan's fertility rate actually fell below 1.0 because it was thought to be a bad year to have children in, the previous year having been considered inauspicious for marriage.[33]) Many couples still live with their parents, and the older generation expects women to stay at home, take care of children, and do house chores.[33] Stipends and subsidies from the government have been unsuccessful in encouraging more people to reproduce,[33] but the government has added more money for childcare, education, and birth subsidies.[30] The government is also considering immigration policies that attract highly skilled workers from other countries,[32] and making English an official language.[30]

At the current rate, Taiwan is set to transition from an aged to a super-aged society, where 21% of the population is over 65 years of age, in eight years, compared to seven years for Singapore, eight years for South Korea, 11 years for Japan, 14 for the United States, 29 for France, and 51 for the United Kingdom.[31] As of 2018, Japan was already a super-aged society,[32] with 27% of its people being older than 65 years.[4] According to government data, Japan's total fertility rate was 1.43 in 2017.[34] According to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Japan has one of the oldest populations in the world, with a median age of 47 years in 2017.[18]

Southeast Asia

.jpg.webp)

Singapore's total fertility rate continues to decline in the 2010s, as more and more young people are choosing to delay or eschew marriage and parenthood. It reached 1.14 in 2018, making it the lowest since 2010 and one of the lowest in the world.[35] Reasons for this include long work hours, digital disruption, uncertainties surrounding global trade, climate change, high cost of living, and long wait times for public housing.[36][37] The median age for first-time mothers rose from 29.7 in 2009 to 30.6 in 2018, which poses a problem because fertility declines with age. Meanwhile, the death rate has been increasing since 1998; Singapore now faces an aging population.[36] In fact, Singapore's birth rate has been below the replacement level of 2.1 since the 1980s, and appears to have stabilized during the first two decades of the twenty-first century. Government incentives such as the baby bonus have proven insufficient to raise the birth rate.[35] The number of women in their prime childbearing years (25–29) who remained single increased from 60.9% in 2007 to 68.1% in 2017. For men, the corresponding numbers were 77.5% and 80.7%, respectively. In Singapore, the singleness rate is a major determinant of fertility because only 10% of married couples have no children at all. While it is not unusual for men to marry late because they are expected to have established themselves before getting married and to be the primary breadwinner, one major reason why women are marrying later is because higher education eliminates the need to get married for economic survival.[37][note 1]

At the 2019 Forbes Global CEO Conference, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said that one of the top issues facing his country is finding the right demographic balance. "To secure our future, we must make our own babies, enough of them. Because if all of the next generation are not our own, then where do they come from and what is the point of this?" he said. Lee added that the long-term goal of his government is to maintain a workforce that is two-thirds Singaporean, with the rest being brought in from overseas. He argued that such a ratio is manageable while relaxing immigration restriction would be "unwise" because "there is no shortage of people who want to come."[38]

Singapore's experience mirrors those of Japan and South Korea.[35]

.jpg.webp)

Vietnam's population grew from 60 million in 1986 to 97 million in 2018, with the rate of growth falling to about one percent in the late 2010s. Like Bangladesh and unlike Egypt, Vietnam is a developing country that has successfully curbed its population growth.[15] Vietnam's median age in 2018 was 26 years and is rising. Between the 1970s and the late 2010s, life expectancy climbed from 60 to 76 years.[39] It is now the second highest in Southeast Asia. Vietnam's fertility rate dropped from 5 children per woman in 1980 to 3.55 in 1990 and then to 1.95 in 2017. In that same year, 23% of the Vietnamese population was 15 years of age or younger, down from almost 40% in 1989. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Vietnam's population is one of the fastest aging in the world. The WHO projected that the proportion of people above the age of 65 would rise from 4% in 2017 to almost 7% by 2030. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), "Vietnam is at risk of growing old before it grows rich."[40] The share of working-age Vietnamese peaked in 2011, when the country's annual GDP per capita at purchasing power parity was $5,024, compared to $32,585 for South Korea, $31,718 for Japan, and $9,526 for China.[39]

In April 2020, Prime Minister of Vietnam Nguyễn Xuân Phúc issued a decision on attaining a demographic balance in the country by raising the fertility rate of localities that are below 2.2, which his government considers the replacement rate, and reducing the number of births in places that are above that mark. To this end, local governments are to invest in family-friendly services such as babysitting and family medicine. A 2016 report from the Ministry of Labor, Invalids, and Social Affairs stated that Vietnam became one of the fasting aging societies on Earth in 2015. Government data showed that in 2019, Vietnam's population was 96.2 million people, the third largest in Southeast Asia, and the fifteenth-largest in the world. Yet many localities had fertility rates well below replacement level, such as Dong Thap (1.34), Ba Ria-Vung Tau (1.37), Ho Chi Minh City (1.36), and Hau Giang (1.57). Phúc's decision discourages women from having children after the age of 35 and instead urges people to marry before the age of 30 and have children early.[41] But some newspaper readers pointed out that such a policy ignores cultural, economic, and social realities. Reasons for Vietnam's falling fertility rate include high costs of child-rearing, youth unemployment leading many to continue to live with their parents until the age of 30, career aspirations, high costs of living in the cities, concerns over national problems (such as child abuse, school violence, food safety, pollution, traffic congestion, and overcrowded hospitals), and international issues (namely overpopulation and climate change).[42] Other rapidly growing Southeast Asian economies, such as the Philippines, saw similar demographic trends.[43]

South Asia and the Middle East

In India, the fertility rate has fallen from 5.9 in 1960 to 2.0 in 2020. In addition, the number of women who would like to have more than one child has declined significantly. The National Family Health Survey of 2018 found that only 24% of Indian women were interested in having a second child, down from 68% a decade prior. As of 2021, India's total fertility rate stood at 2.0, falling below the replacement level of 2.1. Only five states - Bihar, Meghalaya, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand and Manipur have fertility rates above the replacement level.[44] In general, India's falling fertility is correlated with increasing women's literacy rates and level of education, rising economic prosperity, improved mobility, and later marriage.[13] Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been urging couples to have fewer children to make sure they are better taken care of.[27]

Afghanistan's median age in 2017 was 16 years, making it the only country outside of Africa with a median age below 17.[18]

A 2019 study by the Taub Center for Social Policy Studies showed that Israel's fertility rate was 3.1 children per woman, well above all other members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). For comparison, Mexico was in second place at 2.2. Israel therefore had nothing short of a baby boom, comparable to what the United States experienced after World War II. Although ultra-Orthodox women in Israel had a phenomenal birth rate of about seven, Israel's comparatively high rate is not due to highly religious women alone, but rather the national culture and attitude towards having a family. Secular Israeli women had a fertility rate of about 2.2, also high by the standards of the OECD. However, among Arabs living in Israel, family size has declined significantly since the 1960s, to a level less than that of their Jewish counterparts and comparable with the developed world, where women have become more active in the work place. Among Israeli women in general, women's participation in the labor force has increased, as is the case with other developed countries, yet their fertility has not declined, unlike said countries.[45]

Europe

In 2015, a woman living in the European Union had on average 1.5 children, down from 2.6 in 1960.[2]

.jpg.webp)

Italy's fertility rate dropped from about four in the 1960s down to 1.2 in the 2010s. This is not because young Italians do not want to procreate. Quite the contrary, having a lot of children is an Italian ideal. But its economy has been floundering since the Great Recession of 2008, with the youth unemployment rate at 35% in 2019. Many Italians have moved abroad – 150,000 did in 2018 – and many are young people pursuing educational and economic opportunities.[46] The Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) reported that the number of babies born in 2018 in Italy was the lowest since the unification of Italy in 1861.[22] Moreover, the Baby Boomers are retiring in large numbers, and their numbers eclipse those of the young people taking care of them. Only Japan has an age structure more tilted towards the elderly.[46] One possible solution to this problem is incentivizing reproduction, as France has done, by investing in longer parental leaves, daycare, and tax exemptions for parents. As of 2019, France has approximately the same population as Italy but 65% more births.[46] In 2015, Italy introduced a cash handout of €800 per couple per child. This does not seem to have had an impact in the long run. People may choose to have a child earlier, but ultimately, this does not increase the nation's fertility rate. This pattern has also been observed in other countries, family study expert Anne Gauthier of the University of Groningen told the BBC. In Italy's case, the subsidy does not address economic concerns or social attitudes.[47]

.jpg.webp)

Greece's heavy demographic aging comes as a result of economic hardship which has prompted many young people to leave the country in search of better opportunities elsewhere. Between 2009 and 2018, about half a million people left the country, many of them of child-bearing age.[48] In 2010, 115,000 children were born; that number dropped to 92,000 in 2015,[49] and then to below 89,000 in 2017, the lowest on record.[48] In 2019, the fertility rate fell to just 1.3 per woman, well below the replacement level and one of the lowest in Europe. Some of the more remote regions of Greece suffer from shortages of obstetricians and gynecologists, many of whom have gone abroad, which deters would-be parents. In general, the Greeks are having children later and having fewer children in the 2010s compared to the 1980s.[48]

The Spanish National Institute of Statistics reported that the number of babies born in Spain in 2018 was the lowest since 1998 and a 40.7% drop compared to 2008. This is due to the fact that there were fewer women of childbearing age in Spain than in the past, and that modern Spaniards are having fewer children.[22] In Portugal, the fertility rate dropped to 1.3 in the late 2010s. Across Southern Europe, about 20% of women born in the 1970s are childless, a number not seen since the First World War. More and more schools have been forced to close and many towns are becoming empty. Southern Europe could become countries of old people by the late 2030s (when people born in the early 2010s and mid-2020s come of age) if the current trend continues.[50]

Hungary's birth rate was about 1.48 in 2018. For the government of Prime Minister Viktor Orban, which favors "procreation over immigration," raising the national fertility rate is a matter of "strategic importance." In December 2018, the Hungarian government nationalized six fertility clinics and said it would offer free in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment starting February 2020, though the details of who would be eligible for this program remain unclear. Like other Eastern European countries, Hungary faces a declining population not just due to its low birth rate, now half of what it was in 1950, but also to emigration to Western Europe. About one in every seven Hungarian children was born outside Hungary in the 2010s.[51][52]

.jpg.webp)

The United Nations Population Division projected that Russia, which had a birth rate of 1.75 in 2018, would find its population drop from 143 million down to 132 million by 2050.[4] Russia's population has been on the decline since the 1990s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union.[53] Another reason for Russia's demographic decline is the nation's low life expectancy for men, at only 64 years in 2015, or 15 years less than that in Italy, Germany, or Sweden. This is due to a combination of unusually high rates of alcoholism, smoking, untreated cancer, tuberculosis, suicides, violence, and HIV/AIDS.[54] Although previous attempts to raise the birth rate have failed, in 2018, President Vladimir Putin proposed giving money to low-income families, first-time mothers, families with many children, and the creation of more nurseries. This is part of a massive spending package aimed at revitalizing the struggling Russian economy.[53]

Throughout the 2000s, France maintained a fertility rate of about 2.0, but from the early 2010s onward, the country has seen its fertility rate falling gradually.[55] Despite recent declines, France retains one of the highest birth rates in Europe at 1.92 in 2017, according to the World Bank. While many countries have introduced policies intended to incentivize people to have more children, these might be counter-balanced by other policies, such as taxes. In France, the Ministry of Families is solely responsible for family and child benefits packages, which are more generous for larger families.[47]

Germany's fertility rate rose from 1.33 in 2006 to 1.57 in 2017, moving the country away from Spain and Italy and closer to the E.U. average. This is due to a few reasons. Older women were having children, which caused the rate to increase slightly. New immigrants, who arrived in Germany in great numbers in that decade, tend to have more children than natives, though their children will likely assimilate into German society and will have smaller families of their own than their parents and grandparents. In the former West Germany, working mothers were once stigmatized, but this is no longer the case in unified Germany. In the late 2000s and early 2010s, the German federal government introduced more generous parental leave, encouraged fathers to take (more) time off, and increased the number of nurseries, to which the government declared children over one year old were entitled to. Although the supply of nurseries remained insufficient, the number of children enrolled in them rose from 286,000 in 2006 to 762,000 in 2017.[56]

.jpg.webp)

In Sweden, generous pro-natalist policies contribute to the nation having a birth rate of 1.9 in 2017, which was high compared to the rest of Europe. Swedish parents are entitled to 480 days of parental leave to share between both parents, with fathers claiming on average 30% of the amount. According to the European Commission, Sweden has one of the lowest child poverty rates in the E.U. Nevertheless, Sweden's birth rate has begun to fall in the late 2010s.[57] One of the reasons why Sweden has maintained a relatively high birth rate is because the country has for decades been accepting immigrants, who tend to have more children than the average Swede.[58]

Other Nordic countries face the same situation. Denmark, Norway, Finland, and Iceland all saw their fertility rates decline in the late 2010s to between 1.49 and 1.71 from previously near replacement level, although their economies had already recovered from the Great Recession by that time. "The number of childless individuals is growing rapidly, and the number of women having three or more children is going down. This kind of fall is unheard of in modern times in Finland," family sociologist Anna Rotkirch told AFP.[58] According to Statistics Finland, the total fertility rate of that country in 2019 was 1.35, the lowest on record.[59] Causes for this decline include financial uncertainty, urbanization, rising unemployment, declining median income, and high cost of living. Falling fertility rates jeopardize the much prized Nordic welfare systems.[58][60] Generous parental benefits, including subsidized childcare, have proven ineffective in halting the demographic decline.[13] According to a 2020 report from Nordic Council of Ministers, the Finns were aging at a faster rate than any of their counterparts in the Nordic region.[60] Statistics Finland predicted in 2019 that given current trends in fertility and migration, Finland's population would begin to decline by 2031.[61]

.jpg.webp)

According to the World Bank, the Faroe Islands had a birth rate of about 2.5 in 2018, one of the highest in Europe, a position they have maintained for decades. Like the rest of the Nordic region, the territory has implemented a variety of family-friendly policies, such as 46 weeks of parental leave, numerous and cheap kindergartens, and tax cuts, including one for seven-seat vehicles. But unlike the rest of the Nordic region, its urbanization rate is far lower.[62] Accordingly, traditional family values and family ties remain strong. Sociologist Hans Pauli Strøm of Statistics Faroe Islands told the AFP, "In our culture, we perceive a person more as a member of a family than as an independent individual. This close and intimate contact between generations makes it easier to have children." In addition, women's workforce participation is comparatively high, at 82%, compared to an average of 59% for the European Union, of which the Islands are not a member. More than half of Faroese women work part-time as a matter of personal choice rather than labor-market conditions. The autonomous Danish territory in the North Atlantic, in fact, had a prosperous economy, as of the 2010s.[63]

In 2018–19, Ireland had the highest birth rate and the lowest death rate in the European Union, according to Eurostat.[64] Although Ireland had a thriving economy in the mid- to late-2010s, only 61,016 babies were born here in 2018 down from 75,554 in 2009. Ireland's birth rate fell from 16.8 in 2008 to 12.6 in 2018, a drop of about a quarter. The average age of first-time mothers in Ireland was 32.9 in 2018, up by over two years compared to the mid-2000s. Between 2006 and 2016, the number of babies born to women in their 40s doubled while that to teenagers fell by 52.8%. Economist Edgar Morgenroth of Dublin City University told the Irish Times that one of the reasons behind Ireland's falling fertility rate was the fact that Ireland had a baby burst in the 1980s after a baby boom in the 1970s, and the people born in the 1980s were starting families in the 2010s. He further explained that high housing and childcare costs could be behind Irish couples' reluctance. The marriage rate was 4.3 per 1,000 in 2018, the lowest since 1997 even though same-sex marriages were included. In addition, people were getting married later. In 2018, the average age at first marriage for a man was 36.4, up from 33.6 in 2008; for a woman, those figures were 34.4 and 31.7, respectively. Usually, rising birth and marriage rates correspond to a healthy economy, but the present statistics seem to have buckled that trend.[65] As of 2016, Ireland was, demographically, a young country by European standards. However, the country is aging quite quickly. According to the Central Statistics Office, although Ireland had more people below the age of 14 than above the age of 65 in 2016, the situation could flip by 2031 in all projected scenarios, which will pose a problem for public policy. For instance, Ireland's healthcare system, already operating on a tight budget, will be under even more pressure.[66]

.jpg.webp)

England and Wales were experiencing a baby boom in the early 2010s which peaked in 2012.[67] With more children being born in the UK between the middle of 2011 and the middle of 2012 than any year since 1972.[68] However, fertility rates declined as the decade progressed. According to the United Kingdom Office for National Statistics, the fertility rates of England and Wales fell to a record low in 2018. Moreover, they fell for women of all age groups except those in their 40s. A total of 657,076 children were born in England and Wales in 2018, down 10% from 2012. 1977 and 1992-2002 were the only years where these jurisdictions had lower fertility rates on record. As has been the case since the start of the new millennium, the birth rate of women below the age of 20 continues to fall, down to 11.9 in 2018. Before 2004, women in their mid- to late-20s had the highest fertility rate, but between the mid-2000s and the late-2010s, those in their early- to mid-30s held that position. Social statistician and demographer Ann Berrington of the University of Southampton told The Guardian that access to education, "changing aspirations" in life, the availability of emergency and long-acting contraception, and the lack of affordable housing were among the reasons behind the decline in fertility among people in their 20s and 30s.[69] If women were merely delaying childbirth, the fertility of women in their 20s would decline while that of women in their 30s would rise. But this was not the case in the late 2010s. Women in their 40s saw a slight increase, but they accounted for only 5% of all births in the same period. Immigrants have contributed to this decline. Whereas previously they tended to have more children on average than native Britons and were indeed above replacement level, their fertility rate in England and Wales dropped from 2.46 in 2004 to 1.97 in 2020. In other words, the proportions of births to immigrant women have fallen and are now below replacement. The fertility gap is closing.[55] There were 11.1 births per thousand people in 2018, compared to a peak of 20.5 in 1947, and the total fertility rate was 1.70, down from 1.76 in 2017. At the same time, the number of stillbirths – when a baby is born after at least 24 weeks of pregnancy but with no signs of life – fell to a record low for the second consecutive year, standing at 4.1 per a thousand births in 2018.[70] Meanwhile, in Scotland, the fertility rate continues its downward trend since 2008. Figures from the National Records of Scotland (NRS) reveal that 12,580 births were registered in the final quarter of 2018. Except for 2002, this is the lowest since record-keeping began in 1855. NRS explained that economic insecurity and the postponement of motherhood, which often means having fewer children, are among the reasons why.[71]

North America

.jpg.webp)

In Canada, about one in five Millennials were delaying having children because of financial worries. Canada's average non-mortgage debt was CAN$20,000 in 2018. One in three Millennials felt "overwhelmed" by their liabilities, compared to 26% of Generation X and 13% of Baby Boomers, according to consultant firm BDO Canada. More than one in three Canadians with children felt stressed out by debt, compared with one-fifth of those without children. Many Canadian couples in their 20s and 30s are also struggling with their student loan debts.[72] Research by the Royal Bank of Canada suggests that Canadian Millennials have been flocking to the large cities in spite of their expensive costs of living between the mid- and late 2010s in search of economic opportunities and cultural amenities.[73] Data from Statistics Canada reveals that between 2000 and 2017, the birth rate among women under 30 years old fell in all provinces and territories except New Brunswick women between the ages of 25 and 29 whereas that of women of age 30 and over rose everywhere except in Nunavut among women aged 35 to 39. Meanwhile, the adolescent fertility rate (15 to 19) halved in most of Canada, thus leading to fewer teenage pregnancies, a result likely due to improved sex education. The comparatively low birth rate of women in their 20s living in British Columbia and Ontario was correlated with the high housing costs in these provinces. On the other hand, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut had relatively high fertility rates because they have large Indigenous populations, and Indigenous women tend to have more children. (Data for Yukon was not available.)[74]

Statistics Canada reported in 2015 that for the first time in Canadian history, there were more people aged 65 and over than people below the age of 15. One in six Canadians were above the age of 65 in July 2015. If this trend continues, there would be three seniors for every two children below the age of 15 in 20 years.[75]

During the early 2010s, among the various religious groups in Canada, Muslims had the highest fertility rate of all. At 2.4 per woman, they outpaced Hindus (2.0) Sikhs (1.9), Jews (1.8), Christians (1.6), and secular people (1.4).[76] Nationwide, 38.6% of Canadian couples had only one child during the late 2010s.[13]

.jpg.webp)

As their economic prospects improve, most American Millennials say they desire marriage, children, and home ownership.[77] While Millennials were initially responsible for the so-called "back-to-the-city" trend,[78] by the late 2010s, Millennial homeowners were more likely to be in the suburbs than the cities.[79] Besides the cost of living, including housing costs, people are leaving the big cities in search of warmer climates, lower taxes, better economic opportunities, and better school districts for their children.[80][81][82] Exurbs have become quite popular among Millennials as well. The return of suburbanization in the United States is due to not just Millennials reaching a stage in their lives where they start to have children but also to the new economics of space made possible by fast telecommunications technology and e-commerce, effectively cutting perceived distances.[83] According to the Pew Research Center, by 2016, the cumulative number of American women of the millennial generation who had given birth at least once reached 17.3 million. About 1.2 million Millennial women had their first child that year. By the mid-2010s, Millennials, who made up 29% of the adult population and 35% of the workforce of the U.S., were responsible for a majority of births in the nation. In 2016, 48% of Millennial women were mothers, compared to 57% of Generation-X women in 2000 when they were the same age. The increasing age of women when they become mothers for the first time is a trend that can be traced back to the 1970s, if not earlier.[note 2] Factors behind this trend include a declining interest in marriage, the growth in educational attainment, and the rise of women's participation in the workforce.[84] Single-child families were the fastest-growing type of family units in the U.S. during the late 2010s.[13]

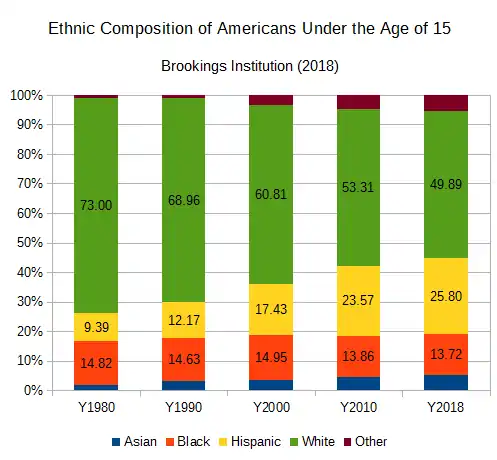

A report from the Brookings Institution stated that in the United States, the Millennials are a bridge between the largely Caucasian pre-Millennials (Generation X and their predecessors) and the more diverse post-Millennials (Generation Z and their successors).[77] Overall, the number of births to Caucasian women in the United States dropped 7% between 2000 and 2018. Among foreign-born Caucasian women, however, the number of births increased by 1% in the same period. Although the number of births to foreign-born Hispanic women fell from 58% in 2000 to 50% in 2018, the share of births due to U.S.-born Hispanic women increased from 20% in 2000 to 24% in 2018. The number of births to foreign-born Asian women rose from 19% in 2000 to 24% in 2018 while that due to U.S.-born Asian women went from 1% in 2000 to 2% in 2018. In all, between 2000 and 2017, more births were to foreign-born than U.S.-born women.[85]

By analyzing data from the Census Bureau, the Pew Research Center discovered that in 2017, at least 20% of kindergartners in public schools were Hispanics in a grand total of 18 U.S. states plus the District of Columbia, compared to only eight states in 2000 and 17 in 2010. Between 2010 and 2017, Massachusetts and Nebraska joined the list while Idaho left. Hispanics, who comprised 18% of the U.S. population (or about 60 million people) have been spreading across the United States since the 1980s and are now the largest minority ethnic group in the nation. They also made up 28% of the students in K-12 public schools in 2019, up from 14% in 1995. For comparison, the number of Asian public-school students increased slightly, from 4% to 6% during the same period. Blacks fell slightly from 17% to 15%, and whites dropped from 65% to 47%. Overall, the number of children born to ethnic minorities has exceeded 50% of the total since 2015.[86]

Provisional data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reveal that U.S. fertility rates have fallen below the replacement level of 2.1 since 1971. In 2017, it dropped to 1.765, the lowest in three decades.[87] 15.4% of the U.S. population was over 65 years of age in 2018.[4] After the Second World War, the U.S. fertility rate peaked in 1958 at 3.77 births per woman, fell to 1.84 in 1980, and climbed to 2.08 in 1990 before declining again in 2007.[88] However, there is great variation in terms of geography, age groups, and ethnicity. South Dakota had the highest birth rate at 2,228 per a thousand women and the District of Columbia the lowest at 1,421. Besides South Dakota, only Utah (2,121) had a birth rate above replacement level.[87] From 2006 to 2016, women whose ages range from the mid-20s to the mid-30s maintained the highest birth rates of all while those in their late 30s and early 40s saw significant increases in birth rates.[89] American women are having children later in life, with the average age at first birth rising to 26.4 in the late 2010s,[88] up from 23 in the mid-1990s.[90] Falling teenage birth rates play a role in this development.[90] In fact, the number of births given by teenagers, which reached ominous levels in the 1990s, have plummeted by about 60% between 2006 and 2016. This is thanks in no small part to the collapse of birth rates among black and Hispanic teens, down 50% from 2006.[91] Overall, births fell for Asians, blacks, Hispanics, and whites but remained stable for native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders.[92] While Hispanic American women still maintained the highest fertility rate of any racial or ethnic groups in the United States, their birth rate dropped 31% between 2007 and 2017. Like their American peers and unlike their immigrant parents and grandparents, young Hispanic American women in the 2010s were more focused on their education and careers and less interested in having children.[93]

That U.S. fertility rates continue to drop is anomalous to demographers because fertility rates typically track the nation's economic health. It was no surprise that U.S. fertility rates dropped during the Great Recession of 2008. But the U.S. economy has shown strong signs of recovery for some time, and birthrates continue to fall. In general, however, American women still tend to have children earlier than their counterparts from other developed countries and the U.S. total fertility rate remains comparatively high for a rich country.[92] In fact, compared with their counterparts from other countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), first-time American mothers were among the youngest on average, on par with Latvian women (26.5 years) during the 2010s. At the other extreme end were women from Italy (30.8), and South Korea (31.4). During the same period, American women ended their childbearing years with more children on average (2.2) than most other developed countries, with the notable exception of Icelandic women (2.3). At the other end were women from Germany, Italy, Spain, and Japan (all 1.5).[94]

Below-replacement-level fertility rates could lead to labor shortages in the future. Speaking to the Associated Press, family specialist Karen Benjamin Guzzo from Bowling Green State University in Ohio recommended childcare subsidies, preschool expansion, (paid) parental leave, housing assistance, and student debt reduction or forgiveness.[92] In any case, while the United States is indeed an aging society, its demographic decline is not as serious as that faced by many other major economies. The number of Americans of working age is predicted to increase by 10% between 2019 and 2040.[20]

In 2019, the fertility rate of Mexico was about 2.2, higher than that of any other member of the OECD except Israel at 3.1.[45]

Oceania

.jpg.webp)

Australia's total fertility rate has fallen from above three in the post-war era, to about replacement level (2.1) in the 1970s to below that in the late 2010s. It stood at 1.74 in 2017. However, immigration has been offsetting the effects of a declining birthrate. In the 2010s, among the residents of Australia, 5% were born in the United Kingdom, 2.5% from China, 2.2% from India, and 1.1% from the Philippines. 84% of new arrivals in the fiscal year of 2016 were below 40 years of age, compared to 54% of those already in the country. Like other immigrant-friendly countries, such as Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, Australia's working-age population is expected to grow till about 2025. However, the ratio of people of working age to dependents and retirees (the dependency ratio) has gone from eight in the 1970s to about four in the 2010s. It could drop to two by the 2060s, depending on immigration levels.[95] "The older the population is, the more people are on welfare benefits, we need more health care, and there's a smaller base to pay the taxes," Ian Harper of the Melbourne Business School told ABC News (Australia).[96] While the government has scaled back plans to increase the retirement age, to cut pensions, and to raise taxes due to public opposition, demographic pressures continue to mount as the buffering effects of immigration are fading away.[95] Australians coming of age in the early twenty-first century are more reluctant to have children compared to their predecessors due to economic reasons: higher student debt, expensive housing, and negative income growth.[96]

Statistics New Zealand reported that the nation's fertility rate in 2017 was 1.81, the lowest on record. Although the total number of births went up, the birth rate went down because of country's larger population thanks to high levels of immigration. New Zealand's fertility rate remained more or less stable between the late 1970s and the late 2010s. Younger women were driving the birth rate down, with those between the ages of 15 and 29 having the lowest birth rates on record. In 2017, New Zealand teenagers had one half the number of babies of 2008, and under a quarter of 1972.[97] Meanwhile, women above the age of 30 were having more children. Between the late 2000s and late 2010s, an average of 60,308 babies were born in New Zealand.[98]

South America

Brazil's fertility rate has fallen from 6.3 in 1960 to 1.7 in 2020. For this reason, the nation's population is projected to decline by the end of the twenty-first century. According to a 2012 study, soap operas featuring small families have contributed to the growing acceptance of having just a few children in a predominantly Catholic country. However, Brazil continues to have relatively high rates of adolescent pregnancies, and the government is working to address this problem.[27]

Notes

- Also see how income affects human mating.

- More broadly, contemporary human females are evolving to reach menarche earlier and menopause later compared to their ancestral counterparts. See human evolution from the Early Modern Period to present.

References

- Williams, Alex (September 19, 2015). "Meet Alpha: The Next 'Next Generation'". Fashion. The New York Times. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- Barry, Sinead (June 19, 2019). "Fertility rate drop will see EU population shrink 13% by year 2100; active graphic". World. Euronews. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- AFP (November 10, 2018). "Developing nations' rising birth rates fuel global baby boom". The Straits Times. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- Duarte, Fernando (April 8, 2018). "Why the world now has more grandparents than grandchildren". Generation Project. BBC News. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Gallagher, James (November 9, 2018). "'Remarkable' decline in fertility rates". Health. BBC News. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Safi, Michael (July 25, 2020). "All the people: what happens if humanity's ranks start to shrink?". World. The Guardian. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- "The pandemic may be leading to fewer babies in rich countries". The Economist. October 28, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- Grantham-Philips, Wyatte (December 17, 2020). "COVID baby boom? No, 2020 triggered a baby bust - and that will have lasting impacts". USA Today. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- Nordstrom, Louise (January 22, 2021). "The baby boom that never was: France sees sharp decline in 'lockdown babies'". France24. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- Wodarz, Dominik; Stipp, Shaun; Hirshleifer, David; Komarova, Natalia L. (April 15, 2020). "Evolutionary dynamics of culturally transmitted, fertility-reducing traits". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 287 (1925). doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.2468. PMC 7211447. PMID 32290801.

- Bricker, Darrell; Ibbitson, John (January 27, 2019). "What goes up: are predictions of a population crisis wrong?". The Observer. The Guardian. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "The UN revises down its population forecasts". Demography. The Economist. June 22, 2019. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- Lopez, Rachel (February 29, 2020). "Baby monitor: See how family size is shrinking". Hindustan Times. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- "The Changing Global Religious Landscape". Religion. Pew Research Center. April 5, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- Walsh, Declan (February 11, 2020). "As Egypt's Population Hits 100 Million, Celebration Is Muted". World. The New York Times. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- Kight, Stef W. (July 21, 2018). "The dangers of Nigeria's population explosion". Axios. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- Myers, Joe (August 30, 2019). "19 of the world's 20 youngest countries are in Africa". World Economic Forum. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- Desjardins, Jeff (April 18, 2019). "Median Age of the Population in Every Country". Visual Capitalist.

- Leng, Sidney (January 17, 2020). "China's birth rate falls to near 60-year low, with 2019 producing fewest babies since 1961". Economy. South China Morning Post. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- LeVine, Steve (July 3, 2019). "Demographics may decide the U.S-China rivalry". World. Axios. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- "China's median age will soon overtake America's". Finance and Economics. The Economist. October 31, 2019. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- "Number of newborns in Japan fall below 900,000 for first time: 5 countries that face falling birth rates". East Asia. Straits Times. December 26, 2019. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- "China's population 'to peak' in 2029 at 1.44 billion". Asia-Pacific. BBC News. January 5, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- Yu, Sun (January 19, 2020). "China's falling birth rate threatens economic growth". The Financial Times. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- Zhang, Phoebe (November 24, 2019). "China's ageing population prompts plan to deal with looming silver shock". Society. South China Morning Post. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- Deyner, Simon; Gowen, Annie (April 24, 2018). "Too many men: China and India battle with the consequences of gender imbalance". South China Morning Post. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- "Seven countries with big (and small) population problems". World. BBC News. July 16, 2020. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- Haas, Benjamin (September 3, 2018). "South Korea's fertility rate set to hit record low of 0.96". South Korea. The Guardian. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- "South Korea's fertility rate drops below one for first time". AFP (via France24). February 27, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- Hsu, Crystal (August 31, 2018). "Population decline might start sooner than forecast". Taipei Times. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Liao, George (April 10, 2018). "MOI: Taiwan officially becomes an aged society with people over 65 years old breaking the 14% mark". Society. Taiwan News. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Steger, Isabella (August 31, 2018). "Taiwan's population could start shrinking in four years". Quartz. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Sui, Cindy (August 15, 2011). "Taiwanese birth rate plummets despite measures". Asia-Pacific. BBC News. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- "Japan enacts legislation making preschool education free in effort to boost low fertility rate". National. Japan Times. May 10, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- Sin, Yuen (March 2, 2018). "Govt aid alone not enough to raise birth rate: Minister". Singapore. Straits Times. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- Sin, Yuen (July 22, 2019). "Number of babies born in Singapore drops to 8-year low". Singapore. Straits Times. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- Au-Yong, Rachel (September 18, 2018). "Singapore's fertility rate down as number of singles goes up". Singapore. The Straits Times. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- Maria, Anna (October 19, 2019). "PM Lee—Singapore needs to make enough of our own babies to secure the future". The Independent (Singapore). Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- "Vietnam is getting old before it gets rich". The Economist. November 8, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- Hutt, David (October 2, 2017). "Will Vietnam Grow Old Before it Gets Rich?". ASEAN Beat. The Diplomat. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- Viet Tuan (May 5, 2020). "Marry early, have kids soon, Vietnam urges citizens". VN Express International. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- Linh Do (May 13, 2020). "Vietnam's about turn on ideal replacement fertility rate meets dissent". VN Express International. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- Business Wire (May 6, 2019). "Focus on the bleak ramifications of falling fertility rates in South East Asian countries". Associated Press. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - "National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5)". rchiips.org. Retrieved 2022-01-28.

- Keyser, Zachary (February 18, 2019). "Israel's fertility rate comparable to U.S. 'baby boom,' study finds". Israel News. Jerusalem Post. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- Livesay, Christopher (November 25, 2019). "In Italy, rising anxiety over falling birth rates". PBS Newshour. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- "How do countries fight falling birth rates?". Europe. BBC News. January 15, 2020. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- Harlan, Chico (December 1, 2018). "Where are all the children? How Greece's financial crisis led to a baby bust". Europe. The Washington Post. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- Brabant, Malcolm (November 13, 2017). "Brain drain and declining birth rate threaten the future of Greece". PBS Newshour. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- The New York Times (April 18, 2017). "S. Europe's birth rate falls to crisis levels". World. The Straits Times. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- "Hungary to provide free fertility treatment to boost population". Europe. BBC News. January 10, 2020. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- Kennedy, Merrit (January 10, 2020). "Hungary Says It Will Offer Free Fertility Treatments To Counter Population Decline". Europe. NPR. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- Soldatkin, Vladimir; Golubkova, Katya (January 15, 2020). "'Our historic duty': Putin plans steps to boost Russia's birth rate". World News. Reuters. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- Meakins, Josh (March 8, 2017). "Why Russia is far less threatening than it seems". Monkey Cage. The Washington Post. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- "Britain's baby bust". Demography. The Economist. July 23, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "Why Germany's birth rate is rising and Italy's isn't". Europe. The Economist. June 29, 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- "How do countries fight falling birth rates?". Europe. BBC News. January 15, 2020. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- AFP (January 1, 2019). "Babies wanted: Nordic countries struggle with falling birth rates". World. The Straits Times. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- Teivainen, Aleksi (January 24, 2020). "Finland's total fertility rate drops to levels of late 1830s, shows preliminary data". Finland. Helsinki Times. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- Teivainen, Aleksi (February 6, 2020). "Finland hit harder by demographic changes than other Nordics, shows report". Finland. Helsinki Times. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- Teivainen, Aleksi (October 1, 2019). "Statistics Finland unveils bleak population forecast – population to start decline in 2031". Finland. Helsinki Times. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- United Nations factsheet as to low urbanization in Faroe Islands

- AFP (June 20, 2018). "Family ties make Faroese women Europe's top baby makers". Denmark. The Local. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- Pope, Connor (July 10, 2019). "Ireland has highest birth rate and lowest death rate in EU". Ireland. Irish Times. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- McGreevy, Ronan (October 18, 2019). "Ireland's birth rate down 25% compared to Celtic Tiger period". Ireland. Irish Times. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- Wall, Martin; Horgan-Jones, Jack (August 24, 2019). "The old country: Get ready for an ageing Ireland". Irish Times. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- "Births in England and Wales - Office for National Statistics". cy.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 2021-10-23.

- "More UK births than any year since 1972, says ONS". BBC News. 2013-08-08. Retrieved 2021-10-23.

- Walker, Amy (August 1, 2019). "Birthrate in England and Wales at all-time low". Lifestyle. The Guardian. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- "Birth rate in England and Wales hits record low". Health. BBC News. August 1, 2019. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- "Scotland's birth rate continues to fall". UK. BBC News. March 13, 2019. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- Alini, Erica (October 10, 2018). "One in 5 Canadian millennials are delaying having kids due to money worries: BDO". Money. Global News. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- Hansen, Jacqueline (April 25, 2019). "Think millennials are leaving Canada's big cities? Think again, RBC report says". Business. CBC News. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- Gibson, John (April 25, 2019). "Who's having babies — and when — has changed dramatically in Canada". Canada. CBC News. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- "More Canadians are 65 and over than under age 15, StatsCan says". Business. CBC News. September 29, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- Todd, Douglas (October 12, 2014). "Think religion is in decline? Look at who is 'going forth and multiplying'". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- Frey, William H. (January 2018). "The millennial generation: A demographic bridge to America's diverse future". The Brookings Institution. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- Schmidt, Ann (July 3, 2019). "Millennials are leaving major cities in droves over rising costs". Fox Business. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- Adamczyk, Alicia (September 29, 2019). "Millennials are fleeing big cities for the suburbs". Money. CNBC. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- Sauter, Michael B. (October 4, 2018). "Population migration patterns: US cities we are flocking to". Money. USA Today. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- Daniels, Jeff (March 20, 2018). "Californians fed up with housing costs and taxes are fleeing state in big numbers". Politics. CNBC. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- Reyes, Cecilia; O'Connell, Patrick (September 25, 2019). "There's a lot of talk about an 'Illinois exodus.' We took a closer look at the reality behind the chatter". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- Adamczyk, Alicia (September 29, 2019). "Millennials are fleeing big cities for the suburbs". Money. CNBC. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- Livingston, Gretchen (May 4, 2018). "More than a million Millennials are becoming moms each year". Fact Tank. Pew Research Center. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Livingston, Gretchen (August 8, 2019). "Hispanic women no longer account for the majority of immigrant births in the U.S." Pew Research Center. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- Krogstad, Jens Manuel (July 31, 2019). "A view of the nation's future through kindergarten demographics". Fact Tank. Pew Research Center. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Howard, Jacqueline (January 10, 2019). "US fertility rate is below level needed to replace population, study says". CNN. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Searing, Linda (January 20, 2020). "The Big Number: U.S. birthrate drops to all-time low of 1.73". Health. The Washington Post. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- Cha, Ariana Eunjung (June 30, 2017). "The U.S. fertility rate just hit a historic low. Why some demographers are freaking out". Health. The Washington Post. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Livingston, Gretchen (January 18, 2018). "They're Waiting Longer, but U.S. Women Today More Likely to Have Children Than a Decade Ago". Social Trends. Pew Research Center. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- Cha, Ariana Eunjung (April 28, 2016). "Teen birthrate hits all-time low, led by 50 percent decline among Hispanics and blacks". Health. The Washington Post. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- Johnson, Carla K. (May 15, 2019). "US births lowest in 3 decades despite improving economy". Associated Press. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Tavernise, Sabrina (March 7, 2019). "Why Birthrates Among Hispanic Americans Have Plummeted". The New York Times. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- Livingston, Gretchen (June 28, 2018). "U.S. women are postponing motherhood, but not as much as those in most other developed nations". Fact Tank. Pew Research Center. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- Fensom, Anthony (December 1, 2019). "Australia's Demographic 'Time Bomb' Has Arrived". The National Interest. Yahoo! News. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- Kohler, Alan; Hobday, Liz. "So many baby boomers are retiring this doctor quit his job to go build them luxury homes". 7.30. ABC News (Australia). Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- Sargent, Ewan (February 19, 2018). "New Zealand's birthrate hits a new low". Lifestyle. Stuff. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- Parenting and fertility trends in New Zealand: 2018. October 23, 2019. ISBN 978-1-98-858364-8. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help)