Depression of 1920–1921

The Depression of 1920–1921 was a sharp deflationary recession in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries, beginning 14 months after the end of World War I. It lasted from January 1920 to July 1921.[1] The extent of the deflation was not only large, but large relative to the accompanying decline in real product.[2]

There was a two-year post–World War I recession immediately following the end of the war, complicating the absorption of millions of veterans into the economy. The economy started to grow, but it had not yet completed all the adjustments in shifting from a wartime to a peacetime economy. Factors identified as contributing to the downturn include returning troops, which created a surge in the civilian labor force and problems in absorbing the veterans; Spanish flu;[3][4] a decline in labor union strife;[6] changes in fiscal and monetary policy; and changes in price expectations.

Following the end of the depression, the Roaring Twenties brought a period of economic prosperity between August 1921 and August 1929, one month before the stock market crash that triggered the start of the Great Depression.

Overview

| Economic data for 1920–1921 recession[2][7][8] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Production | Prices | Ratio |

| 1920–1921 (Commerce) | −6.9% | −18% | 2.6 |

| 1920–1921 (Balke & Gordon) | −3.5% | −13% | 3.7 |

| 1920–1921 (Romer) | −2.4% | −14.8% | 6.3 |

| 1929–1930 | −8.6% | −2.5% | 0.3 |

| 1930–1931 | −6.5% | −8.8% | 1.4 |

| 1931–1932 | −13.1% | −10.3% | 0.8 |

The recession lasted from January 1920 to July 1921, or 18 months, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research. This was longer than most post–World War I recessions, but was shorter than recessions of 1910–1912 and 1913–1914 (24 and 23 months respectively). It was significantly shorter than the Great Depression (132 months).[1][9] Estimates for the decline in Gross National Product also vary: The U.S. Department of Commerce estimates that GNP declined 6.9%; Nathan Balke and Robert J. Gordon estimate a decline of 3.5%; and Christina Romer estimates a decline of 2.4%.[2][10] There is no formal definition of economic depression, but two informal rules are a 10% decline in GDP or a recession lasting more than three years, and the unemployment rate climbing above 10%.[11]

The recession of 1920–1921 was characterized by extreme deflation, the largest one-year percentage decline in around 140 years of data.[2] The Department of Commerce estimates 18% deflation, Balke and Gordon estimate 13% deflation, and Romer estimates 14.8% deflation. Wholesale prices fell 36.8%, the most severe drop since the American Revolutionary War. This is worse than any year during the Great Depression (although adding all the years of the Great Depression together yields more cumulative deflation). The deflation of 1920–21 was extreme in absolute terms, and also unusually extreme given the relatively small decline in gross domestic product.[2]

| Unemployment rate[12] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Lebergott | Romer |

| 1919 | 1.4% | 3.0% |

| 1920 | 5.2% | 5.2% |

| 1921 | 11.7% | 8.7% |

| 1922 | 6.7% | 6.9% |

| 1923 | 2.4% | 4.8% |

Unemployment rose sharply during the recession. Romer estimates a rise to 8.7% from 5.2% and an older estimate from Stanley Lebergott says unemployment rose from 5.2% to 11.7%. Both agree that unemployment quickly fell after the recession, and by 1923 had returned to a level consistent with full employment.[12] During the recession, there was an extremely sharp decline in industrial production. From May 1920 to July 1921, automobile production declined by 60% and total industrial production by 30%.[13] At the end of the recession, production quickly rebounded. Industrial production returned to its peak levels by October 1922. The AT&T Index of Industrial Productivity showed a decline of 29.4%, followed by an increase of 60.1%—by this measure, the recession of 1920–21 had the most severe decline and most robust recovery of any recession between 1899 and the Great Depression.[14]

Using a variety of indexes, Victor Zarnowitz found the recession of 1920–21 to have the largest drop in business activity of any recession between 1873 and the Great Depression. (By this measure, Zarnowitz finds the recession to be only slightly larger than the Recession of 1873–1879, Recession of 1882–1885, Recession of 1893–1894, and the Recession of 1907–1908.)[14]

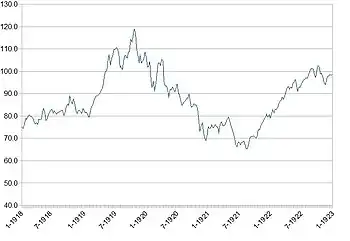

Stocks fell dramatically during the recession. The Dow Jones Industrial Average reached a peak of 119.6 on November 3, 1919, two months before the recession began. The market bottomed on August 24, 1921, at 63.9, a decline of 47% (by comparison, the Dow fell 44% during the Panic of 1907 and 89% during the Great Depression).[15] The climate was terrible for businesses—from 1919 to 1922 the rate of business failures tripled, climbing from 37 failures to 120 failures per every 10,000 businesses. Businesses that avoided bankruptcy saw a 75% decline in profits.[13]

Causes

Factors that economists have pointed to as potentially causing or contributing to the downturn include troops returning from the war, which created a surge in the civilian labor force and more unemployment and wage stagnation; a decline in agricultural commodity prices because of the post-war recovery of European agricultural output, which increased supply; tighter monetary policy to combat the postwar inflation of 1919; and expectations of future deflation that led to reduced investment.[2]

End of World War I

Adjusting from war time to peacetime was an enormous shock for the U.S. economy. Factories focused on wartime production had to shut down or retool their production. A short recession occurring in the United States following Armistice Day was followed by a growth spurt. The recession that occurred in 1920, however, was also affected by the adjustments following the end of the war, particularly the demobilization of soldiers. One of the biggest adjustments was the re-entry of soldiers into the civilian labor force. In 1918, the Armed Forces employed 2.9 million people. This fell to 1.5 million in 1919 and 380,000 by 1920. The effects on the labor market were most striking in 1920, when the civilian labor force increased by 1.6 million people, or 4.1%, in a single year. (Though smaller than the numbers in post–World War II demobilization in 1946 and 1947, this is otherwise the largest documented one-year labor force increase.)[2] In the early 1920s, both prices and wages changed more quickly than today. Employers may have been quicker to offer reduced wages to returning troops, hence lowering their production costs, and lowering their prices.[2]

1918–1920 flu pandemic

The Spanish flu pandemic in the United States began in spring 1918 and returned in waves into 1920, killing about 675,000 Americans. Because a large fraction of the deaths were among working age adults, the resulting economic dislocation was especially severe. Work by economists Robert Barro and Jose Ursua suggests that the flu was responsible for declines in gross domestic product of 6 to 8 percent worldwide between 1919 and 1921.[3][4]

Labor unions

During World War I, labor unions had increased their power—the government had a great need for goods and services, and with so many young men in the military, there was a tight labor market. Following the war, however, there was a period of turmoil for labor unions, as they lost their bargaining power. In 1919, 4 million workers went on strike at some point, significantly more than the 1.2 million in the preceding years.[2] Major strikes included an iron and steel workers strike in September 1919, a bituminous coal miners strike in November 1919, and a major railroad strike in 1920. According to economist J. R. Vernon, "By the spring of 1920, with unemployment rates rising, labor ceased its aggressive stance and labor peace returned."[2]

Monetary policy

Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, in A Monetary History of the United States, consider mistakes in Federal Reserve policy as a key factor in the crisis. In response to post–World War I inflation the Federal Reserve Bank of New York began raising interest rates sharply. In December 1919 the rate was raised from 4.75% to 5%. A month later it was raised to 6%, and in June 1920 it was raised to 7% (the highest interest rates of any period except the 1970s and early 1980s).

Deflationary expectations

Under the gold standard, a period of significant inflation of bank credit and paper claims would be followed by a wave of redemptions as depositors and speculators moved to secure their assets. This would lead to a deflationary period as bank credit and claims diminished and the money supply contracted in line with gold reserves. The introduction of the Federal Reserve System in 1913 had not fundamentally altered this link to gold.[16] The economy had been generally inflationary since 1896, and from 1914 to 1920, prices had increased quickly. People and businesses thus expected prices to fall substantially.[2]

Government response

President Woodrow Wilson's slow response to the depression was criticized by those in the Republican party, catapulting them into the White House under the banner of Warren Harding. Once in office, Harding convened a President's Conference on Unemployment at the instigation of then Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover as a result of rising unemployment during the recession. About 300 eminent members of industry, banking, and labor were called together in September 1921 to discuss the problem of unemployment. Hoover organized the economic conference and a committee on unemployment. The committee established a branch in every state having substantial unemployment, along with sub-branches in local communities and mayors' emergency committees in 31 cities. The committee contributed relief to the unemployed, and also organized collaboration between the local and federal governments. President Harding signed the Emergency Tariff of 1921 and the Fordney–McCumber Tariff. Secretary of Treasury Andrew Mellon also successfully pushed for lower income tax rates to help the recovery.

Interpretations

According to a 1989 analysis by Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, the recession of 1920–1921 was the result of an unnecessary contractionary monetary policy by the Federal Reserve Bank.[17] Paul Krugman agrees that high interest rates due to the Fed's effort to fight inflation caused the problem. This did not cause a deficiency in aggregate demand but in aggregate supply. Once the Fed relaxed its monetary policy, the economy rapidly recovered.[18]

Additionally, Allan H. Meltzer suggests that since the U.S. was on the gold standard, the flight of gold from hyper-inflationary Europe to the U.S. raised the nominal stock of high-powered base money. This ended the deflation and contributed to the economic recovery.[19]

James Grant discusses in his 2014 book, The Forgotten Depression, 1921, why the depression of 1920–1921 was relatively short compared to the 21st century's economic recession and the following economic downturn that started in 2007. "The essential point about the long ago downturn of 1920–1921 is that it was kind of the last demonstration of how a price mechanism works and the last governmentally unmediated business cycle downturn, meaning it was the last one that the government didn't attempt to treat with fiscal intervention with much lower interest rates. In fact, the FED, then still wet behind the ears as it only had been founded in 1914, actually raised rates in the face of a truly brutal deflation."[20]

Thomas Woods, a proponent of the Austrian School, argues that President Harding's laissez-faire economic policies during the 1920–1921 recession, combined with a coordinated aggressive policy of rapid government downsizing, had a direct influence on the rapid and widespread private-sector recovery.[21] Woods argued that, as there were massive distortions in private markets due to government economic influence related to demands of World War I, an equally massive correction to the distortions needed to occur as quickly as possible to realign investment and consumption with the new peacetime economic environment.

In a 2011 article, Daniel Kuehn, a proponent of Keynesian economics, questions many of the assertions Woods makes about the 1920–1921 recession.[22] Kuehn notes the following:

- the most substantial downsizing of government was attributable to the Wilson administration, and occurred well before the onset of the 1920–1921 recession.

- the Harding administration raised revenues in 1921 by expanding the tax base considerably at the same time that it lowered rates.

- Woods underemphasizes the role the monetary stimulus played in reviving the depressed economy and that, since the 1920–1921 recession was not characterized by a deficiency in aggregate demand, fiscal stimulus was unwarranted.

United Kingdom

Britain initially enjoyed an economic boom between 1919–1920, as private capital pent-up over four years of war was invested into the economy.[23] The shipbuilding industry was flooded with orders to replace lost shipping (7.9 million tons worth of merchant shipping stock was destroyed during the war). However, by 1920, the British transition from a wartime to a peacetime economy faltered, and a serious recession struck the economy between 1920–1922. James Mitchell, Solomos Solomou and Martin Weale have estimated that GDP fell sharply by 22% between August 1920 and May 1921. They estimate that output did not exceed the 1920 level until the spring of 1924.[24] With other major economies also mired in recession, the export-dependent economy of Britain was particularly hard-hit. Unemployment reached 17%, with overall exports at only half of their pre-war levels.[23]

References

- US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions, National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved on September 22, 2008.

- Vernon, J. R. (July 1991). "The 1920-21 Deflation: The Role of Aggregate Supply". Economic Inquiry. 29 (3): 572–580. doi:10.1111/j.1465-7295.1991.tb00847.x.

- Barro, Robert J.; Ursua, Jose F. (2008). "Macroeconomic Crises since 1870". Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. The Brookings Institution. 39 (1): 255–350. doi:10.3386/w13940.

- Barro, Robert J.; Ursua, Jose F. (May 5, 2009). "Pandemics and Depressions". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Digital History". www.digitalhistory.uh.edu. Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- Lawrence H. Officer, "The Annual Consumer Price Index for the United States, 1774–2008", MeasuringWorth, 2009. URL: http://www.measuringworth.org/uscpi/

- Louis D. Johnston and Samuel H. Williamson, "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?" MeasuringWorth, 2008. URL: http://www.measuringworth.org/usgdp/

- "Great Depression | Definition, History, Causes, Effects, & Facts".

- Christina Duckworth Romer (1988). "World War I and the postwar depression; A reinterpretation based on alternative estimates of GNP". Journal of Monetary Economics. 22 (1): 91–115. doi:10.1016/0304-3932(88)90171-7.

- "Diagnosing depression". The Economist. December 30, 2008.

- Romer, Christina (1986). "Spurious Volatility in Historical Unemployment Data" (PDF). The Journal of Political Economy. 91: 1–37. doi:10.1086/261361. S2CID 15302777. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2009-09-30.

- Anthony Patrick O'Brien (1997). "Depression of 1920–1921". In David Glasner, Thomas F. Cooley (ed.). Business cycles and depressions: an encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing. pp. 151–153.

- Zarnowitz, Victor (1996). Business Cycles. University of Chicago Press.

- "Dow Historical Timeline". Dow Jones Industrial Average. Archived from the original on 2014-10-20. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- Wicker, Elmus R. (1966). "A Reconsideration of Federal Reserve Policy during the 1920–1921 Depression". Journal of Economic History. 26 (2): 223–238. doi:10.1017/S0022050700068674. JSTOR 2116229. S2CID 154805899.

- Romer, Christina; Romer, David (1989). "Does Monetary Policy Matter? A New Test in the Spirit of Friedman and Schwartz" (PDF). NBER Macroeconomics Annual. 4: 121–170. doi:10.2307/3584969. JSTOR 3584969.

- Krugman, Paul (April 1, 2011). "1921 and All That". The New York Times.

- Allan H. Metzer, "Lessons from the Early History of the Federal Reserve" Archived 2012-07-22 at the Wayback Machine (Presidential Address to International Atlantic Economic Society)

- James Grant, The Forgotten Depression, 1921— The Crash That Cured Itself, Simon & Schuster, 2014

- Thomas Woods. "Warren Harding and the Forgotten Depression of 1920", First Principles Journal.

- Kuehn, Daniel (September 2011). "A critique of Powell, Woods, and Murphy on the 1920–1921 depression". Review of Austrian Economics. 24 (3): 273–291. doi:10.1007/s11138-010-0131-3. S2CID 145586147.

- Carter & Mears (2011). A History of Britain: Liberal England, World War and Slump. London: Stacey International. p. 154. ISBN 978-1906768485.

- Mitchell, Solomou, Weale, James, Solomou, Martin (2011). "Monthly GDP Estimates for Interwar Britain" (PDF). Pdf. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Bordo, Michael D., and John Landon-Lane. "Exits from Recessions: The US Experience 1920–2007" . No. w15731. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2010. online

- Friedman, Milton; Schwartz, Anna J. (1993) [1963]. A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 231–239. ISBN 978-0691003542.

- Leab, Daniel, ed. Encyclopedia of American Recessions and Depressions (2 vol ABC-CLIO, 2014).

- Meltzer, Allan H. (2003). A History of the Federal Reserve – Volume 1: 1913–1951. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 109–131. ISBN 978-0226520001.

- Nelson, Daniel. "'A Newly Appreciated Art:' The Development of Personnel Work at Leeds & Northrup, 1915–1923." Business History Review 44.4 (1970): 520–535.

- Newman, Patrick. "The depression of 1920–1921: a credit induced boom and a market based recovery?." Review of Austrian Economics 29.4 (2016): 387–414.

- Shaw, Christopher W. “'We Must Deflate': The Crime of 1920 Revisited." Enterprise & Society 17.3 (2016): 618-650. online.

- Tallman, Ellis, and Eugene N. White. "Monetary Policy When One Size Does Not Fit All: the Federal Reserve Banks and the Recession of 1920–1921." Workshop on Monetary and Financial History Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and Emory University (2017) online.

- Wicker, Elmus R (1966). "A Reconsideration of Federal Reserve Policy during the 1920–1921 Depression". Journal of Economic History. 26 (2): 223–238. doi:10.1017/s0022050700068674. JSTOR 2116229. S2CID 154805899.

- Committee of the President's Conference on Unemployment (1923). Business Cycles and Unemployment. National Bureau of Economic Research. ISBN 0-87014-003-5.

External links

- Smiley, Gene. "US Economy in the 1920s". EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. March 26, 2008.