Depsang Plains

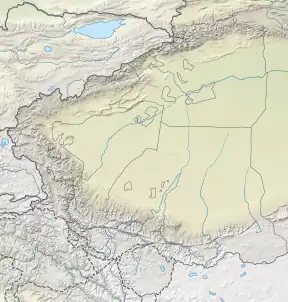

The Depsang Plains, a high-altitude gravelly plain in the northwest portion of the disputed Aksai Chin region of Kashmir, divided into Indian and Chinese administered portions by a Line of Actual Control.[2][3] India controls the western portion of the plains as part of Ladakh, while the eastern portion is controlled by China and claimed by India.[4] The Line of Control with Pakistan-administered Gilgit-Baltistan is 80 kilometres (50 mi) west of the Depsang Plains, with the Siachen Glacier in-between.[5] Ladakh's traditional trade route to Central Asia passed through the Depsang Plains, with the Karakoram Pass lying directly to its north.

| Depsang Plains | |

|---|---|

Depsang Plains  Depsang Plains  Depsang Plains | |

| Floor elevation | 17,400 ft (5,300 m)[1] |

| Length | 25 mi (40 km) east-west [1] |

| Width | 12–13 mi (19–21 km) north-south [1] |

| Area | 310 sq mi (800 km2) |

| Geography | |

| Country | India, China |

| State | Ladakh, Xinjiang |

| Region | Aksai Chin |

| District | Leh district, Hotan County |

| Coordinates | 35.32°N 77.99°E |

| River | Chip Chap River Tributaries of Karakash River Tributaries of Burtsa Nala |

| Depsang Plains | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 達普桑平地 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 达普桑平地 | ||||||

| |||||||

The Depsang plains are also part of the area called Sub-Sector North (SSN) by the Indian military.[6] The area sees frequent tension between China and India. Major standoffs between the two countries occurred in 2013, 2015 and 2020.

Name

Depsang (or Dipsang) means 'open, elevated plain' in Tibetan.[7]

Geography

(and points on the "traditional customary boundary" of China declared in 1960).[8][lower-alpha 1]

The Depsang plains are located in the north-western Aksai Chin.[9] They are bounded on the north by the valley of the Chip Chap River and on the west by the Shyok River. On the east, they are bounded by low hills of the Lak Tsung range, which separate them from the basin of the Karakash River. In the south, the Depsang Plains proper end at the Depsang La pass, but in common parlance, the Depsang region is taken to include the mountainous region to the south of it, including the "Depsang Bulge". The latter is a bulge in theoretical Indian territory, housing the upper course of the Burtsa Nala.

The Karakoram Pass is located to the north of the Depsang Plains, while the Lingzi Thang plains lie to the southeast. On the west is the southern part of the Rimo glacier, the source of the Shyok River.[10]

Francis Younghusband, who travelled here in the late 19th century, described the area as follows:[11]

The Depsang Plains are more than seventeen thousand feet above sea-level, and are of gravel, as bare as a gravel-walk to a suburban villa. Away behind us the snowy peaks of Saser and Nubra appeared above the horizon like the sails of some huge ships; but before us was nothing but gravel plains and great gravel mounds, terribly desolate and depressing. Across these plains blew blinding squalls of snow, and at night, though it was now the middle of summer, there were several degrees of frost.

Line of Actual Control

In 1962, China and India fought a war over the border dispute, following which the Depsang Plains have been divided between the two countries across a Line of Actual Control (LAC), which runs east of the traditional caravan route. Now only the militaries of the two countries inhabit the region, distributed into numerous military camps. The nearest inhabited village is Murgo.[12]

Locations

Burtsa, alternately spelled as Burtse, is a historic halting spot on the caravan route at the southern end of the Depsang Plains, where the Depsang Nala joins the Burtsa Nala.[lower-alpha 2] It currently serves as a military camp of the Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP) and the Indian Army on the Darbuk-Shyok-DBO road, about 15 kilometres on the India's side of the LAC.[13][14]

North of Burtsa is Qizil Langar, also called Qazi Langar. It lies in a narrow, reddish gorge, immediately to the south of the Depasang La.[15] The Depsang Nala stream flows in the gorge from the west and takes a turn to the south at Qizil Langar. Depsang Nala joins the Burtsa Nala a little to the south of Burtsa and the combined river flows west and drains into the Murgo Nala near the village of Murgo.

Gapshan or Yapshan is a halting place at the confluence of the Chip Chap River and the Shyok River.[16][17] In the past, on numerous occasions, the Chong Kumdan glacier has blocked the flow of the Shyok River forming a lake called the Gapshan Lake; once the ice dam melts, the lake drains away.[18][19] From Gapshan, the Shahi Kangri group of peaks dominate the plains.[20][17]

At a campground, Polu (or Pulo/Pola) is a traditional temporary shelter built using local mud, four miles north of DBO along the DBO Nala, Maj A. M. Sethi found a memorial stone left by Dr. Ph. C. Visser in 1935.[21]

Tianwendian ("astronomical point") is a border post in the Chinese-controlled territory. It was established after the 1962 war. Before that, another post called Point 5243 served as the main base. From Tianwendian Defence Area, the Chinese have a line of sight extending to Siachen glacier, 140 km away. Closer to the Indian-controlled territory is forward post 5390, a PLA observation point which acts as an extension of Tianwendian.[22][23] The Tiankong Highway runs parallel to the LAC, connecting Tianwendian and Kongka to the south.

History

Caravan route

.jpg.webp)

The Depsang Plains were regularly traversed by trade caravans, coming via the Karakoram Pass in the north from Yarkand beyond. Filippo de Filippi, who explored the area in 1913–1914, described:[24]

... the caravans come and go incessantly, in the summer, in astonishing numbers. The first one of the season passed on June 28th, coming from Sanju on the Yarkand road; then more and larger ones came; in July there were four in one day, almost all travelling from Central Asia toward Leh—the Ladakhis usually do their trading at home. The caravans were of all sizes, from small groups of 3 or 4 men with 5 or 6 animals to large parties with 40 or more pack-animals; the men on foot or riding asses, the better-to-do merchants on caparisoned horses ...

Filippi also wrote that the experienced caravaners passed through the Depsang Plains without stopping, travelling a distance of 31 miles between Daulat Beg Oldi and Murgo in a single day.[25] Others stopped, either at Qizil Langar to the south of Depsang La, or at Burtsa further south. A stream running from below Depsang La, called Depsang Nala, waters these parts leading to the growth of the burtza plant, which served as fodder as well as fuel for the campers.[26]

The trading caravans declined during the 1940s during tensions in Xinjiang (Chinese Turkestan) and completely stopped in the 1950s.[27] In 1953, the Indian consulate in Kashgar was closed down. The Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru told the Parliament that the Chinese wish to treat Xinjiang as a "closed area". Subsequently, China built the Xinjiang–Tibet highway through Aksai Chin starting the Sino-Indian border dispute, which persists till the present day.[28]

In modern times, the Darbuk–Shyok–DBO Road (DS–DBO Road) has been laid by India along the old caravan route. From south to north, it passes through Sultan Chushku, Murgo, Burtsa and Qizil Langar, to reach Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO).

Exploration

In 1893, Charles Murray, 7th Earl of Dunmore, in his daily records of his travels with Major Roche through Ladakh, Tibet and Pamirs, wrote of seeing musk deer, kiang, Tibetan antelope and a butterfly in the region in and around the Depsang Plains. Dunmore noted that K2, the second highest mountain in the world, could be seen from the plateaus.[29] In 1906, Sven Hedin had travelled east from Burtsa to the Aksai Chin lake on the traditional silk road.[30] The traditional route to Shahidula passed through the plains; Kizil Jilga to Haji Langar to Shahidula.[9]

Flora and fauna

The Depsang Plains are widely observed as forming a high-altitude cold desert without any flora or fauna.[31] Filippo de Filippi, who explored the region in the 1910s, wrote that "the surface of the [Depsang] plateau is a mass of minute detritus, and is entirely devoid of vegetation, except for occasional patches of a yellowish-green plant".[32] A 1985 expedition to the Rimo Glacier found blooming plants at a few places and that "at places [the] plains are marshy and our mules were sinking and we all had to help them out."[33] Burtse (Artemisia spp.) plant of the Asteraceae family grows along the Burtsa Nala and Depsang Nala, lending its name to the region. Its leaves were used for fodder and its roots as firewood by caravaners.[34][35] Potentilla pamirica is also found in the plains.[36]

Small populations of Tibetan antelope (or "chiru"), mountain weasel, Ladakh pika, bharal (blue sheep), Tibetan wolf and woolly hare, among others, can seen in the plains.[37] According to Brigadier Teg B Kapur, "the [Depsang] plain abounds with wild horses and hares".[38] The populations of chiru are migratory and come to the high-altitude plains for summer grazing.[37][39] These populations are also the westernmost population of chiru, found at altitudes of up to 5500m.[40][41] A Schaller Conservation Survey of chiru conducted by the Wildlife Trust of India in 2005 sighted 149 individuals of chiru in 22 groups, all females and kids, in the Depsang area. The southernmost area where chiru were spotted was the Thuksu Doon Doon nullah which flows near the Depsang La.[37][42] The report says that "Chiru is a mixed feeder and favoured graminoids and forb plant species".[37] In the past, Chiru were killed for their fine wool (called shahtoosh) and many efforts have been taken to protect them in India.[37][41][42] Populations of Kiang also move back and forth across the disputed border.[39] In 1990, it was reported that the proposed Daultberg–Depsang Sanctuary would contain the last wild yak,[39] but Schaller Conservation Survey did not locate any in the 2000s.[37]

DRDO-reared double-humped Bactrian camels (originally used along the silk route) will be deployed at DBO and Depsang by the Indian Army for patrolling and transportation.[43] Zanskar ponies are also being used by the Indian Army.[43]

Sino-Indian border dispute

.jpg.webp)

The Republic of China (1912–1949), having faced a revolution in Tibet in 1911, apparently made secret plans to acquire Aksai Chin plateau in order to create a road link between Xinjiang and Tibet. These plans began to get manifested in public maps only towards the end of its rule.[45]

While the Republic of China claims included the Aksai Chin proper, they stopped at the foot of the Karakoram mountains, leaving all the rivers that flow into the Shyok River within India, including the Chip Chap River. (See map.) Communist China also published the "Big Map of the People's Republic of China" in 1956 with a similar boundary, now called the 1956 claim line.[46][47]

However, in 1960 China advanced its claim line further west, dissecting the Chip Chap River.[47] The Chinese said little by way of justification for this advancement other than to claim that it was their "traditional customary boundary" which was allegedly formed through a "long historical process". They claimed that the line was altered in the recent past only due to "British imperialism".[lower-alpha 5][48][49][50]

Meanwhile, India continued to claim the entire Aksai Chin plateau.

1962 war

India's Intelligence Bureau patrols had come across indications of Chinese activity in the Depsang Plains prior to 1958.[9] However, the Bureau chief B. N. Mullik has stated that "the Chinese did not come into Depsang Plains till October, 1960".[51]

The 1962 Sino-Indian War in the Depsang Plains lasted two days, 20–21 October 1962. The Chinese forces in the area were based at Point 5243 in the present day Tianwendian area. The Indian posts, set up in accordance with India's "forward policy", were manned by the 14th battalion of the Jammu and Kashmir Militia (later Ladakh Scouts), and were mostly of a platoon or a section strength.[52]

The Chinese forces first targeted the post they called "Indian Stronghold No. 6" at "Red Top Hill". They regarded this post specially threatening to their lines of communication.[52] As per the Chinese assessment, the attacking troops had a superiority of 10 to 1 in numbers and 7 to 1 in fire power. The post was eliminated in under two hours, with 42 soldiers killed and 20 captured.[53] Following on this success, the Chinese eliminated 6–7 other Indian posts of a section strength (8–10 troops) and 2 further posts on the second day.[53]

The remaining Indian posts were then given permission to withdraw, as they were not tactically sited and had no mutual support. By 24 October, the withdrawal was completed, with the Indians continuing to hold Saser Brangsa, Murgo, Sultan Chushku and the Galwan estuary on the Shyok River.[53] The Chinese forces advanced to their 1960 claim line in most locations.[53] The one exception was the Burtsa Nala valley to the south of Depsang Plains, where the Chinese eliminated the "bulge" in the Indian territory granted in 1960. This area, called Depsang Bulge, continues to be contested till the present day.[54][55][56][57]

Depsang Bulge conflicts

India continues to maintain the bulge in the Indian territory as per China's 1960 claim line as Indian territory, while its troops have been asked to patrol up to the ceasefire line marked on Indian maps (which has been referred to as the Patrol Point 10 or PP-10).[58]

In April 2013, the Chinese PLA troops set up a temporary camp at the mouth of Depsang Bulge, where the Raki Nala and Depsang Nala meet, claiming it to be Chinese territory. But, after a three-week standoff, they withdrew as a result of a diplomatic agreement with India.[59][60][61][62][63][64] In 2015, China tried setting up a watch tower near Burtsa.[65][66] Any threat to Depsang affects India's DS-DBO road.[10] Initially India had stationed about 120 tanks in the SSN, and over the years this number has increased.[10]

During the 2020 China–India standoff, the Depsang Bulge was again mentioned as one of the areas where China extended its claims. It came to light that the Chinese troops had been blocking Indian patrols from proceeding along the Raki Nala valley near a location called "bottleneck" since 2017.[67] After a resolution to the standoff at Pangong Lake in February 2021, it was reported that the Chinese started strengthening their positions at Depsang.[68]

The new line being demanded by China amounted to a loss of 250 square kilometres of territory for India,[69] while the loss from India's perception of the Line of Actual Control was 900 square kilometres.[70]

Sub Sector North

The Indian military's Subsector North (SSN) is east of Siachen Glacier, located between the Saser ridge on the southeastern side and the Saltoro Ridge on the Pakistani border. With regards to a two–front war for India, this area can provide for a linkage for Pakistan and China in Ladakh.[44][71] The territorial wedge created by Depsang Plains–Karakoram Pass–Shyok Valley prevents this territorial linkup.[71]

See also

Notes

- The border shown is that marked by the contributors to OpenStreetMap. It may not be fully accurate.

- There were actually two campsites called Burtsa Gongma ("upper Burtsa") and Burtsa Yogma ("lower Burtsa"). Only ruined shelters now exist from those sites.

- Even though the map is of very low resolution, it is apparent that the Chip Chap River is shown entirely within Ladakh. Qaratagh-su, a stream that flows down from the Qaratagh Pass and joins the Karakash River is shown as the source of Karakash. Karackattu, The Corrosive Compromise (2020, Figure 1) gives more detailed maps showing Samzungling and Galwan river as part of Ladakh.

- Map by the US Army Headquarters in 1962. In addition to the two claim lines, the blue line indicates the position in 1959, the purple line that in September 1962 prior to the Sino-Indian War, and the orange line, which largely coincides with the dark brown line, the position the end of the war. The dotted lines bound a 20-km demilitarisation zone proposed by China after the war.

- But the military justification for the advancement is not hard to see. The 1956 claim line ran along the watershed dividing the Shyok River basin and the Lingzitang lake basin. It conceded the strategic higher ground of the Karakoram Range to India. The 1960 claim line advanced it to the Karakoram ridge line despite the fact that it did not form a dividing line of watersheds.

References

- Filippi, The Italian Expedition (1932), p. 308.

- "Ladakh incursion: India turns to diplomacy to counter belligerent China amid border stand-off", India Today, 25 April 2013

- Manoj Joshi (7 May 2013). "Making sense of the Depsang incursion". The Hindu.

- "Khurshid to visit China on May 9, no date for flag meet", Hindustan Times, 25 April 2013, archived from the original on 25 April 2013

- Kaushik, Krishn (17 September 2020), "No ground lost in Depsang but India hasn't accessed large parts for 15 years", The Indian Express, retrieved 18 September 2020

- Singh, Rahul (8 August 2020), "Indian, Chinese armies hold talks on Ladakh's Depsang plains", Hindustan Times

- Mehra, An "agreed" frontier (1992).

- India, Ministry of External Affairs, ed. (1962), Report of the Officials of the Governments of India and the People's Republic of China on the Boundary Question, Government of India Press, Chinese Report, Part 1 (PDF) (Report). pp. 4–5.

The location and terrain features of this traditional customary boundary line are now described as follows in three sectors, western, middle and eastern. ... The portion between Sinkiang and Ladakh for its entire length runs along the Karakoram Mountain range. Its specific location is as follows: From the Karakoram Pass it runs eastwards along the watershed between the tributaries of the Yarkand River on the one hand and the Shyok River on the other to a point approximately 78° 05' E, 35° 33' N, turns southwestwards and runs along a gully to approximately 78° 01' E, 35° 21' N; where it crosses the Chipchap River. It then turns south-east along the mountain ridge and passes through peak 6,845 (approximately 78° 12' E, 34° 57' N) and peak 6,598 (approximately 78° 13' E, 34° 54' N). - Palit, D. K. (1991). War in High Himalaya: The Indian Army in Crisis, 1962. Hurst. pp. 32, 43. ISBN 978-1-85065-103-1.

- Philip, Snehesh Alex (19 September 2020), "Why Depsang Plains, eyed by China, is crucial for India's defence in Ladakh", ThePrint-US, retrieved 19 September 2020

- Younghusband, Francis (1904), The Heart of a Continent, Charles Scribner & Sons, pp. 195–196 – via archive.org

- A skull from Daulat Baig Oldie, The Tribune (Chandigarh), 26 May 2019.

- Khanna, Rohit (29 June 2020), "Arunachal to Ladakh, China Has Intruded: Can India Stay in Denial?", TheQuint

- IANS (27 June 2020), "China has occupied Y junction in Ladakh: Sibal", Outlook India

- Dainelli, Giotto (1933). Buddhists and Glaciers of Western Tibet. Kegal, Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. p. 217 – via archive.org.

- Kapadia, High Himalayas (2002), p. 307.

- Kapadia, Into the Untravelled Himalaya (2005), p. 188.

- Mason, Major Kenneth (1929). "Indus Floods and Shyok Glaciers". Himalayan Journal. Vol. 01/3.

- "The Himalayas - Ladakh Himalayas - Glaciers - Biafo and Chong Kumdan". www.schoolnet.org.za. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

-

"Karakoram Photos Part II", Himalayan Camping, retrieved 18 September 2020,

Shahi Kangri dominates the Depsang plains

- Kapadia, High Himalayas (2002), p. 306.

- Sandhu, Shankar & Dwivedi, 1962 from the Other Side of the Hill (2015), pp. 44–46.

- Bhat, Col Vinayak (25 June 2020). "New radar, water pipelines: Satellite images decode Chinese troop movement in Ladakh's Depsang". India Today.

- Filippi, The Italian Expedition (1932), p. 311.

- Filippi, The Italian Expedition (1932), p. 312.

- Bhattacharji, Ladakh (2012), Chapter 15. The Final frontier: Upper Shyok.

- Fewkes, Jacqueline H. (2008), Trade and Contemporary Society Along the Silk Road: An Ethno-history of Ladakh, Routledge, pp. 140–142, ISBN 978-1-135-97309-4

- Claude Arpi, We shut our eyes once, let's not do so again, The Pioneer, 23 March 2017. ProQuest 1879722382

- Dunmore (1893). The Pamirs - Vol.1. John Murry, London. pp. 191–194 – via archive.org.

- Karkra, B. K. (23 October 2019). The Police Warriors on The Indo-Chinese Border in Ladakh. Walnut Publication. pp. 14, 87. ISBN 978-81-943486-1-0.

- Kumar, Maj Gen Brajesh (18 September 2020). "Why Depsang Plains Are The New Conflict Point For India & China". The Dialogue. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- de Filippi, Filippo (1915). "Expedition to the Karakoram and Central Asia, 1913-1914". The Geographical Journal. 46 (2): 92: 85–99. doi:10.2307/1780168. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 1780168.

- Sharma, G. K. (1985). "Ascents in Rimo Group of Peaks : Himalayan Journal vol.41/18". www.himalayanclub.org. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- Bora, Nirmala (2004). Ladakh: Society and Economy. Anamika Publishers & Distributors. p. 123. ISBN 978-81-7975-012-4.

-

Muni, Vineeta, "India Travelogue Adventure: Mountaineering, Trekking, Climbing- Across the Himalayas Part 5", www.indiatravelogue.com, retrieved 18 September 2020,

We climbed up to Depsang La, 5,475 m from Burtse Gongma, slowly gaining altitude. Burtse is a name of a plant that grows there and can be used for firewood.

- Kumar, Amit; Adhikari, Bhupendra Singh; Rawat, Gopal Singh (26 June 2016). "View of New phytogeographically noteworthy plant records from Uttarakhand, western Himalaya, India | Journal of Threatened Taxa". Journal of Threatened Taxa. 8 (6): 8943–8947. doi:10.11609/jott.2416.8.6.8943-8947. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- Sarkar, Prabal; Takpa, Jigmet; Ahmad, Riyaz; Tiwari, Sandeep Kumar; Pendharkar, Anand; Saleem-ul-Haq; Miandad, Javaid; Upadhyay, Ashwini; Kaul, Rahul (2008). Mountain Migrants: Survey of Tibetan Antelope (Pantholops Hodgsonii) and Wild Yak (Bos Grunniens) in Ladakh, Jammu & Kashmir, India (PDF). Conservation action series. Wildlife Trust of India.

- Kapur, Teg Bahadur (1987). Ladakh, the Wonderland: A Geographical, Historical, and Sociological Study. Delhi: Mittal Publications. p. 9. ISBN 978-81-7099-011-6.

- Fox, Joseph L.; Nurbu, Chering; Chundawat, Raghunandan S. (26 February 1991). "The Mountain Ungulates of Ladakh, India" (PDF). Biological Conservation. Elsevier. 58 (2): 186. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(91)90118-S – via snowleopardnetwork.org/.

- Ahmad, Khursheed; Kumar, Ved P.; Joshi, Bheem Dutt; Raza, Mohamed; Nigam, Parag; Khan, Anzara Anjum; Goyal, Surendra P. (2016). "Genetic diversity of the Tibetan antelope (Pantholops hodgsonii) population of Ladakh, India, its relationship with other populations and conservation implications". BMC Research Notes. 9 (477): 477. doi:10.1186/s13104-016-2271-4. PMC 5073904. PMID 27769305. S2CID 15629934.

It is clear that there has been reported migration and exchange of individuals towards the western part in its range, but habitat suitability analysis is needed for a better understanding of the reasons for lack of major exchange of individuals between the westernmost (Depsang Plains close to DBO in northern Ladakh and Aksi Chin near Kunlun range) and other populations.

- Ahmad, Khursheed; Bhat, Aijaz Ahmad; Ahmad, Riyaz; Suhail, Intesar (2020). "Wild Mammalian Diversity in Jammu and Kashmir State". Biodiversity of the Himalaya: Jammu and Kashmir State. Topics in Biodiversity and Conservation. Vol. 18. p. 945. doi:10.1007/978-981-32-9174-4_36. ISBN 978-981-32-9173-7. S2CID 213922370.

Chiru is a keystone species and world's hardiest mountain ungulates that can survive in temperatures as low as –40C. Most of their distribution range falls above 4,000 m, and in Depsang Plains in northern Ladakh, they can be found as high as 5500 m. [...] The Shahtoosh is banned as chiru are killed for Shahtoosh, from which fine woolen yarn is produced which commands a high price in the market

- Ahmad, Khursheed; Ahmad, Riyaz; Nigam, Parag; Takpa, Jigmet (2017). "Analysis of temporal population trend and conservation of Tibetan Antelope in Chang Chenmo Valley and Daulat beg Oldi, Changthang, Ladakh, India". Gnusletter. 34 (2): 16–20.

- Bhalla, Abhishek (19 September 2020). "Indian Army to use double-humped camels for transportation, patrolling in Ladakh". India Today. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- Sushant, Singh (17 September 2020), "What Rajnath Left Out: PLA Blocks Access to 900 Sq Km of Indian Territory in Depsang", The Wire, retrieved 18 September 2020

- Hudson, Aksai Chin (1963), pp. 17–18: "As a part of India, it [Aksai Chin] formed an awkward salient projecting between Sinkiang and Tibet; to get rid of this salient must be an objective of Chinese policy whenever opportunity might offer".

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), p. 103: 'However, the "Big Map of the People's Republic of China" published in 1956, reverted to the alignment shown on the 1947 Kuomintang map. It is important to note that Chou En-lai, in a letter of December 17, 1959, stated that the 1956 map "correctly shows the traditional boundary between the two countries in this sector."'

- Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis (1990), pp. 76, 93

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), pp. 7–8: "When questioned on the divergence between the two maps, Chen Yi, the Chinese Foreign Minister, made the demonstrably absurd assertion that the boundaries as marked on both maps were equally valid. There is only one interpretation that could make this statement meaningful: this was an implied threat to produce another map claiming additional Indian territory if New Delhi continued in its stubborn refusal to cede Aksai Chin."

- Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India (2010), p. 266: "Beijing insisted that there was no disparity between its maps of 1956 and 1960, a claim that only served to reinforce Delhi’s opinion that the Chinese were untrustworthy. By the summer of 1960 meaningful diplomacy juddered to a halt."

- van Eekelen, Indian Foreign Policy and the Border Dispute (1967), pp. 101–102: "The Chinese officials maintained ... [the] traditional customary line, reflected in their map, was formed gradually through a long historical process, mainly by the extent up to which each side had exercised administrative jurisdiction;... Without admitting any inconsistency they also argued that the line of actual control differed from the traditional customary line because of British imperialism and the recent pushing forward of India. These factors apparently could not contribute to the continuous process of change."

- Mullik, B. N. (1971), My Years with Nehru: The Chinese Betrayal, Allied Publishers, p. 627

- Sandhu, Shankar & Dwivedi, 1962 from the Other Side of the Hill (2015), p. 52.

- Sandhu, Shankar & Dwivedi, 1962 from the Other Side of the Hill (2015), p. 53.

- P. J. S. Sandhu, It Is Time to Accept How Badly India Misread Chinese Intentions in 1962 – and 2020, The Wire, 21 July 2020. "However, there was one exception and that was in the Depsang Plain (southeast of Karakoram Pass) where they seemed to have overstepped their Claim Line and straightened the eastward bulge."

- Chinese Aggression in Maps: Ten maps, with an introduction and explanatory notes, Publications Division, Government of India, 1963 (via claurdearpi.net). Map 2.

- Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis (1990), Map 6: India's Forward Policy, A Chinese View, p. 105

- ILLUSTRATION DES PROPOSITIONS DE LA CONFERENCE DE COLOMBO - SECTEUR OCCIDENTAL, claudearpi.net, retrieved 7 October 2020.

- Praveen Swami, As PLA Seeks to Cut Off Indian Patrol Routes on LAC, ‘Bottleneck’ Emerges as Roadblock in Disengagement, News18, 24 June 2020.

- "Chinese incursion 19km, but 750 sq km at stake for India", The Times of India, 2 May 2013, archived from the original on 3 May 2013, retrieved 15 March 2014

- "China puts pre-conditions to pull back, wants India to give up its posts", Indian Express, 24 April 2013, retrieved 15 March 2014

- "Depsang Bulge incursion accidental, Chinese military thinktank says", The Times of India, 15 July 2013, archived from the original on 18 July 2013

- Praveen Swami (29 April 2013), "China's Ladakh intrusion: Two maps tell this dangerous story", Firstpost

- "Let's shake hands: 20 days on, China withdraws troops from Ladakh", India Today, 5 May 2013, retrieved 15 March 2014

- PTI (2013), "Chinese troops enter 25km into Indian territory", Livemint, retrieved 18 September 2020

- "LAC tense as China sets up watch tower near Burtse in northern Ladakh", India Today, 13 September 2015

- "Ladakh again: India, China in standoff over surveillance structure by PLA", The Indian Express, 13 September 2015

- Snehesh Alex Philip, India-China tensions at Depsang, a disengagement sticking point, began much before May, The Print, 8 August 2020.

- Imran Ahmed Siddiqui, Chinese army continues to strengthen position at Ladakh's Depsang Plains, The Telegraph (India), 3 March 2021.

- "China Gained Ground on India During Bloody Summer in Himalayas". Bloomberg News. 1 November 2020.

- Singh, Vijaita (31 August 2020). "China controls 1,000 sq. km of area in Ladakh, say intelligence inputs". The Hindu. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- Banerjee, Lt Gen Gautam (2019). "7: The Hub of OBOR. Where Five National Boundaries Meet". China's Great Leap Forward-II: The China Pakistan Economic Corridor and Strategic Reshaping of Indian Neighbourhood. Lancer Publishers LLC. pp. 88–. ISBN 978-1-940988-43-6.

Bibliography

- Bhattacharji, Romesh (2012), Ladakh: Changing, Yet Unchanged, New Delhi: Rupa Publications – via Academia.edu

- Filippi, Filippo de (1932), The Italian Expedition to the Himalaya, Karakoram and Eastern Turkestan (1913-1914), London: Edward Arnold & Co. – via archive.org

- Fisher, Margaret Welpley; Rose, Leo E.; Huttenback, Robert A. (1963). Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh. Praeger.

- Hoffmann, Steven A. (1990), India and the China Crisis, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06537-6

- Hudson, Geoffrey Francis (1963). "The Aksai Chin". Far Eastern Affairs. Chatto & Windus.

- Kapadia, Harish (1994). High Himalayas, Unknown Valleys (Second ed.). Indus Publishing. ISBN 81-85182-87-6 – via archive.org.

- Kapadia, Harish (2002), High Himalaya Unknown Valleys (Fourth ed.), Indus Publishing, ISBN 978-81-7387-117-7

- Kapadia, Harish (2005), Into the Untravelled Himalaya: Travels, Treks, and Climbs, Indus Publishing, ISBN 978-81-7387-181-8

- Karackattu, Joe Thomas (26 May 2020). "The corrosive compromise of the Sino-Indian border management framework: from Doklam to Galwan". Asian Affairs. 51 (3): 590–604. doi:10.1080/03068374.2020.1804726. S2CID 222093756.

- Mehra, Parshotam (1992), An "agreed" frontier: Ladakh and India's northernmost borders, 1846-1947, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-562758-9

- Raghavan, S. (27 August 2010). War and Peace in Modern India. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-0-230-24215-9.

- Sandhu, P. J. S.; Shankar, Vinay; Dwivedi, G. G. (2015), 1962: A View from the Other Side of the Hill, Vij Books India Pvt Ltd, ISBN 978-93-84464-37-0

- van Eekelen, Willem Frederik (1967). Indian Foreign Policy and the Border Dispute with China. Springer Netherlands. ISBN 978-94-017-6436-0.

Further reading

- Harris, Paul (1998), "Traces of Silk Journey to the Karakoram Pass", Himalayan Journal, vol. 54, no. 13

- Murgo to Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO), Karakoram Story, Himalayan Camping, 10 January 2008.