Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The deputy prime minister of the United Kingdom is a member of the British Cabinet. The title is not always in use and prime ministers have been known to appoint informal deputies without the title of deputy prime minister. The incumbent deputy prime minister is Oliver Dowden.

| Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland | |

|---|---|

_(2022).svg.png.webp) | |

| Government of the United Kingdom Cabinet Office | |

| Style |

|

| Member of | |

| Reports to | Prime Minister |

| Residence | None, may use grace and favour residences |

| Seat | Westminster, London |

| Nominator | Prime Minister |

| Appointer | The King (on the advice of the prime minister) |

| Term length | No fixed term |

| Formation | 19 February 1942 |

| First holder | Clement Attlee |

| Political offices in the UK government |

|---|

_(2022).svg.png.webp) Arms of the British Government |

| List of political offices |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Politics of the United Kingdom |

|---|

_(2022).svg.png.webp) |

|

Constitutional position

Deputy prime minister is a title.[1][2][3] The position of deputy prime minister by itself carries no salary under the Ministerial and other Salaries Act 1975 and the holder has no right to automatic succession to the premiership.[4][5]

Successive monarchs have refused to officially recognise the position of deputy prime minister.[6][7][8] When Winston Churchill attempted to have Anthony Eden appointed deputy prime minister in 1942, George VI said that the 'office... does not exist' and that conferring the title may be seen as an attempt to designate the prime minister's successor and thus may restrict the monarch's royal prerogative.[6] However, Vernon Bogdanor has said that that argument holds little weight in the modern context, since the monarch no longer has any real discretion, and that, even in the past, a person acting as deputy prime minister had no real advantage to being appointed prime minister.[6]

The title is not always in use and the holder's responsibilities will vary depending on the circumstances.[9] Jonathan Kirkup and Steven Thornton suggest that there are multiple motivations behind a prime minister appointing a deputy: leader of a party in a coalition government, as their designated successor, to neuter or mollify a rival, because they are a 'safe pair of hands' and to create a 'balanced ticket'.[10] Philip Norton has written that there are two advantages to a prime minister of having a deputy prime minister (or first secretary of state): functional (to serve the prime minister free of departmental responsibilities, so they can do "correlation, co-ordination and chairmanship of committees" in the words of Rab Butler) and political (to send a signal as to the status of the holder).[11] Bogdanor, Rodney Brazier and Anthony Seldon also suggest that the title may be of use if a prime minister were to die or fall unable to exercise their functions.[6][12][13]

When the position has been in use in the past, the deputy prime minister has deputised for the prime minister at Prime Minister's Questions.[14]

History

Before World War II, while a minister was occasionally invited to deputise as prime minister when the prime minister was ill or abroad, no one was styled as such when the prime minister was in the country and physically able to run the government.[15] This changed in 1942 when Clement Attlee was appointed deputy prime minister, though such a designation was seen as an exceptional result of a coalition and the war.[16] The designation was because Prime Minister Winston Churchill wanted to demonstrate the importance of the Labour party in the coalition, not for any reasons relating to succession; he actually left written advice that the King should send for Anthony Eden if he were to die, not Attlee.[4]

After this, fearing a possible curtailment of the monarch's prerogative to choose a prime minister, no one was formally styled deputy prime minister (though there was often a senior minister generally regarded as such) until Michael Heseltine in 1995 was formally styled deputy prime minister.[17] John Prescott was formally styled as such under Tony Blair and remains the longest serving deputy prime minister.[2] Leader of the Liberal Democrats Nick Clegg was deputy prime minister under David Cameron, in the Cameron-Clegg coalition between 2010 and 2015.[2] Later, Dominic Raab gained the title as part of Boris Johnson's 2021 reshuffle.[18] Thérèse Coffey was Liz Truss's deputy prime minister,[19] before Raab was reappointed to the role under Rishi Sunak in October 2022.[20] Following Raab's resignation, Oliver Dowden gained the title in April 2023, with the GOV.UK announcement notably listing Dowden separately to those who had had their appointments approved by the King.[21]

Office and residence

There is no set of offices permanently ready to house the deputy prime minister.[22] Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg maintained an office at the Cabinet Office headquarters, 70 Whitehall, which is linked to 10 Downing Street.[23] Clegg's predecessor, Prescott, maintained his main office at 26 Whitehall.[24]

The prime minister may also give them the use of a grace and favour country house.[22] While in office, Nick Clegg resided at his private residence in Putney and he shared Chevening House with First Secretary William Hague as a weekend residence.[25] Clegg's predecessor, John Prescott, used Dorneywood.[22]

List of deputy prime ministers

The following people have held the title of deputy prime minister.[Note 1][26][27]

- In his list of deputy prime ministers, Brazier includes Geoffrey Howe. However, Norton does not in his, explaining that Buckingham Palace took issue with appointing Howe "Deputy Prime Minister" and proposed "Sir Geoffrey will act as Deputy Prime Minister".

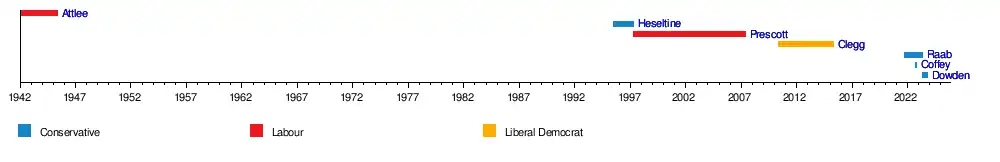

Timeline

Unofficial deputies

The prime minister's second-in-command has variably served as deputy prime minister, first secretary and de facto deputy and at other times prime ministers have chosen not to select a permanent deputy at all, preferring ad hoc arrangements.[16] It has also been suggested that the office of Lord President of the Council (which comes with leading precedence) has been intermittently used for deputies in the past.[28][2]

Lists

.jpg.webp)

Picking out definitive deputies to the prime minister has been described as a highly problematic task.[29]

Bogdanor, in his 1995 publication The Monarchy and the Constitution, said that the following people had acted as deputy prime ministers (by this he meant they had chaired the Cabinet in the absence of the prime minister and chaired a number of key Cabinet Committees):[30]

| Clement Attlee |

| Herbert Morrison |

| Anthony Eden |

| Rab Butler |

| George Brown |

| Michael Stewart |

| Reginald Maudling |

| Willie Whitelaw |

| Geoffrey Howe |

In an academic article first published in 2015, Jonathan Kirkup and Stephen Thornton used five criteria to identify deputies: gazetted or styled in Hansard as deputy prime minister; 'officially' designated deputy prime minister by the prime minister; widely recognised by their colleagues as deputy prime minister; second in the ministerial ranking; and chaired the Cabinet or took Prime Minister's Questions in the prime minister's absence.[31] They said that the following people have the best claim to the position of deputy to the prime minister:[29]

| Clement Attlee |

| Herbert Morrison |

| Anthony Eden |

| Rab Butler |

| George Brown |

| Michael Stewart |

| Willie Whitelaw |

| Geoffrey Howe |

| Michael Heseltine |

| John Prescott |

| Nick Clegg |

They also said that the following three people would have a reasonable claim:[29]

| Bonar Law |

| Edward Short |

| Michael Foot |

Brazier has listed the following ministers as unambiguously deputy to or de facto deputies of the prime minister:[32]

| Clement Attlee | 1940–1945 |

| Anthony Eden | 1945 1951–1955 |

| Rab Butler | 1955–1963 |

| George Brown | 1964–1970 |

| Reginald Maudling | 1970–1972 |

| Willie Whitelaw | 1979–1988 |

| Geoffrey Howe | 1989–1990 |

| Michael Heseltine | 1995–1997 |

| John Prescott | 1997–2007 |

| Nick Clegg | 2010–2015 |

| George Osborne | 2015–2016 |

| Damian Green | 2017 |

| David Lidington | 2018–2019 |

| Dominic Raab | 2019–2022 |

Lord Norton of Louth has listed the following people as serving as deputy prime minister, but not being formally styled as such:[33]

| Herbert Morrison | 1945–1951 |

| Anthony Eden | 1951–1955 |

| Rab Butler | 1962–1963 |

| Willie Whitelaw | 1979–1988 |

| Geoffrey Howe | 1989–1990 |

| David Lidington | 2018–2019 |

Succession

Nobody has the right of automatic succession to the prime ministership.[34] However, it is generally considered that in the event of the death of the prime minister, it would be appropriate to appoint an interim prime minister, though there is some debate as to how to decide who this should be.[35] In 2021, Cabinet Secretary Simon Case suggested:[36]

[I]t would likely have to be a decision for Cabinet to nominate somebody who could step into the role of Prime Minister in the belief that they could fulfil that requirement and command a majority in the House. The sovereign would need to be given a rapid and clear recommendation by the Government on who to call on. By our estimation, and given the pressures of the job, we do not think you would want to leave it for more than 48 hours before identifying such a person.

When the prime minister is travelling, it is standard practice for a senior duty minister to be appointed who can attend to urgent business and meetings if required, though the prime minister remains in charge and updated throughout.[37] And, on 6 April 2020, when Prime Minister Boris Johnson was admitted into ICU, he asked First Secretary of State Dominic Raab "to deputise for him where necessary".[38]

See also

Notes

- Kirkup & Thornton 2017, p. 494.

- Norton 2020, p. 144.

- "The Cabinet Manual" (PDF). Government of the United Kingdom. October 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- Seldon, Meakin & Thoms 2021, p. 171.

- Norton 2020, p. 152.

- Bogdanor 1995, p. 88.

- Kirkup & Thornton 2017, p. 493.

- Thornton, Stephen; Kirkup, Stephen (22 December 2017). "Was Damian Green really the Deputy Prime Minister?". London School of Economics. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- "The Cabinet Manual" (PDF). Government of the United Kingdom. October 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- Kirkup & Thornton 2017, p. 498.

- Norton 2020, p. 148-150.

- Brazier 2020, p. 82-83.

- Seldon, Meakin & Thoms 2021, p. 329.

- Priddy, Sarah (19 October 2020). "Attendance of the Prime Minister at Prime Minister's Questions (PMQs) since 1979". parliament.uk. Archived from the original on 24 April 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- Norton 2020, p. 141-142.

- Norton 2020, p. 142.

- Norton 2020, p. 142-144.

- "Cabinet reshuffle: Losers, winners and challenges ahead". BBC News. 15 September 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- "Liz Truss: New prime minister installs allies in key cabinet roles". BBC News. 6 September 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- "Rishi Sunak's cabinet: Who is in the prime minister's top team?". BBC News. 25 October 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- "Ministerial Appointments: April 2023". UK Government. 24 April 2023. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- Brazier 2020, p. 73.

- "Nick Clegg could be given use of stately home where John Prescott played croquet". The Telegraph. 13 May 2010. Archived from the original on 17 September 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- "Deputy Prime Minister | Contact us". gov.uk. Archived from the original on 16 May 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- "Hague and Clegg given timeshare of official residence". BBC News. 18 May 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- Norton 2020, p. 143-144.

- Brazier 2020, p. 77.

- Seldon, Meakin & Thoms 2021, p. 157.

- Kirkup & Thornton 2017, p. 517.

- Bogdanor 1995, p. 87-88.

- Kirkup & Thornton 2017, p. 495.

- Brazier 2020, p. 80-82.

- Norton 2020, p. 143.

- Brazier 2020, p. 174.

- Norton 2016, p. 34.

- "Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee: Oral evidence: The work of the Cabinet Office, HC 118". Parliament of the United Kingdom. 26 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- Mason, Chris (15 August 2016). "Is Boris Johnson running the country?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- "Statement from Downing Street: 6 April 2020". gov.uk. 6 April 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

References

- Brazier, Rodney (1988). "The deputy prime minister". Public Law.

- Brazier, Rodney (2020). Choosing a Prime Minister: The Transfer of Power in Britain. Oxford University Press.

- Bogdanor, Vernon (1995). The Monarchy and the Constitution. Clarendon Press.

- Hennessy, Peter (1995). The Hidden Wiring: Unearthing the British Constitution. Indigo.

- Kirkup, Jonathan; Thornton, Stephen (2017). "'Everyone needs a Willie': The elusive position of deputy to the British prime minister". British Politics. 12 (4): 492–520. doi:10.1057/bp.2015.42. S2CID 156861636.

- Norton, Philip (2016). "A temporary occupant of No.10? Prime Ministerial succession in the event of the death of the incumbent". Public Law.

- Norton, Philip (2020). Governing Britain: Parliament, Ministers and Our Ambiguous Constitution. Manchester University Press.

- Seldon, Anthony; Meakin, Jonathan; Thoms, Illias (2021). The Impossible Office? The History of the British Prime Minister. Cambridge University Press.

- Vennard, Andrew (2008). "Prime Ministerial succession". Public Law.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)