Serbian Despotate

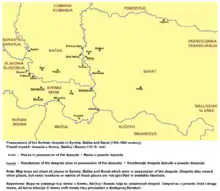

The Serbian Despotate (Serbian: Српска деспотовина / Srpska despotovina) was a medieval Serbian state in the first half of the 15th century. Although the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 is mistakenly considered the end of medieval Serbia, the Despotate, a successor of the Serbian Empire and Moravian Serbia, lasted for another sixty years, experiencing a cultural, economic and political renaissance, especially during the reign of despot Stefan Lazarević. After the death of despot Đurađ Branković in 1456, the Despotate continued to exist for another three years before it finally fell under Ottoman rule in 1459.

Serbian Despotate | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

-en.svg.png.webp) The Serbian Despotate in 1422 | |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Beograd Smederevo Bar | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Serbian | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Serbian Orthodox | ||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Serbian, Serb | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||

| Despot | |||||||||||||||||

• 1402–1427 | Stefan Lazarević | ||||||||||||||||

• 1427–1456 | Đurađ Branković | ||||||||||||||||

• 1456–1458 | Lazar Branković | ||||||||||||||||

• 1458–1459 | Stefan Branković | ||||||||||||||||

• 1459 | Stefan Tomašević | ||||||||||||||||

| Establishment | |||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle ages | ||||||||||||||||

• Establishment | 22 February 1402 | ||||||||||||||||

• Conquest by the Ottoman Empire | 1439 | ||||||||||||||||

• Reestablishment | 1444 | ||||||||||||||||

• Reconquest by the Ottoman Empire | 20 June 1459 | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Serbian dinar | ||||||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | RS | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Serbia Montenegro | ||||||||||||||||

After 1459, political traditions of the Serbian Despotate continued to exist in exile, in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary, with several titular despots of Serbia, who were appointed by kings of Hungary. The last titular Despot of Serbia was Pavle Bakić, who fell in the Battle of Gorjani in 1537.[1]

History

Origins

After Prince Lazar Hrebeljanović was killed in the Battle of Kosovo on June 28, 1389, his son Stefan Lazarević succeeded him. Being a minor, his mother Princess Milica ruled as his regent. A wise and diplomatic woman, she managed to balance the Ottoman threat as the Ottoman Empire was in a turmoil after the Battle of Kosovo and the killing of Sultan Murad I. She married her daughter, Olivera, to his successor, Sultan Bayezid I.

After the battle, in 1390 or 1391 depending on source, Serbia became a vassal Ottoman state, and Stefan Lazarević was obliged to participate in battles if ordered by the Ottoman sultan. He did so in the Battle of Rovine in May 1395 against the Wallachian prince Mircea I and the Battle of Nicopolis in 1396 against the Hungarian king Sigismund. After that, Sultan Bayezid awarded Stefan with the majority of the Vuk Branković's land on Kosovo, as Branković sided with the Hungarian king at Nicopolis.

When Timur's army entered the Ottoman realm, Stefan Lazarević participated in the Battle of Ankara in 1402, in which the Ottomans were defeated and their leader Bayezid was captured. Returning to Serbia, Stefan visited Constantinople where the Byzantine emperor Manuel II Palaiologos granted him the title of despot. In previous years, this title would mean that the despot would rule some vassal state; however, as the Byzantine Empire was too weak to assert such a rule and Serbia was not its vassal state, Stefan Lazarević took this title as the personal style of the Serbian monarchs.

Stefan Lazarević

| History of Serbia |

|---|

|

|

|

Consolidation

Already in Constantinople, Stefan had a dispute with his nephew Đurađ Branković, son of Vuk Branković who was accompanying him and was arrested by the Byzantine authorities. Đurađ would later succeed Stefan. Stefan's brother Vuk Lazarević was also in his escort and as they were returning over the Kosovo, they were attacked by the Branković army at Tripolje, near the Gračanica monastery. Vuk headed the Lazarević army, which was victorious, but reaching Novo Brdo, the brothers had a quarrel and Vuk went to the Ottoman side, to the new sultan (actually co-ruler with his three brothers) Suleyman (I) Çelebi.

Counting on unrest within the Ottoman Empire (Ottoman Interregnum), in early 1404 Stefan accepted vassalage to the Hungarian king Sigismund, who awarded him with Belgrade, the Mačva region, and the fort of Golubac,[2] until then in possession of the Kingdom of Hungary, so Belgrade became a capital of Serbia for the second time in history after King Dragutin.

The next few years are marked by events in Stefan's personal life. He managed to liberate his sister and Bayezid's widow Olivera. In 1404 he made peace with his brother Vuk, in 1405 he married Caterina Gattilusio, daughter of Francesco II Gattilusio, ruler of the island of Lesbos. Also in 1405 his mother Milica died.

In 1408 brothers disputed again and Vuk, together with sultan Suleyman and the Branković family, attacked Stefan in early 1409. Being besieged at Belgrade, Stefan agreed to give southern part of Serbia to his brother and to accept again Ottoman vassalage. Suleyman's brother Musa rebelled against him and Stefan took Musa's side in the battle of Kosmidion in 1410, near Constantinople. Musa's army was defeated and Suleiman sent Vuk and Đurađ Branković's brother Lazar to come to Serbia before Stefan returned, but they both were captured by Musa's sympathizers and were executed in July 1410. Through Constantinople, where Emperor Manuel II confirmed his despotic rights, Stefan returned to Belgrade and annexed Vuk's lands.

In 1410 King Sigismund of Hungary seized several territories in north-eastern Bosnia. As a reward for Stefan Lazarević's help and loyalty, he transferred Srebrenica with its surroundings to the Serbian Despotate in 1411 or 1412.[3]

When Musa became self-proclaimed sultan in European part of the Ottoman Empire, he attacked Serbia in early 1412 but was defeated by Stefan near Novo Brdo in Kosovo. Stefan then invited the ruler of the Anatolian part of the empire, sultan Mehmed Çelebi to attack Musa together. Securing Hungarian help, they attacked Musa on 5 July 1413 at the Battle of Çamurlu, near the Vitosha mountain (modern Bulgaria) and defeated him, with Musa being killed in the battle. As a reward, Stefan received the town of Koprijan near Niš and the Serbian-Bulgarian area of Znepolje.[4] For next twelve years, Stefan remained in good relations with Mehmed, which made the recovery of medieval Serbia possible.

On 28 April 1421, Stefan's nephew and ruler of Zeta, Balša III died without an heir, bequeathing before death his lands to his uncle.[5] With this and territorial gains from the Kingdom of Hungary (Belgrade, Srebrenica, etc.), Serbia restored majority of its ethnic territories it occupied before the Battle of Kosovo.

In 1425, the Ottoman Empire invaded Serbia, burning and pillaging across the Southern Morava valley. At the same time, the King of Bosnia attempted to conquer Srebrenica back from the Serbs, but failed. Despot Stefan fought back the invasion and initiated negotiations with the Sultan, after which the Ottoman troops left Serbia.[6] Still, this attack was an ominous sign of things to come.

Artistic development

The rule of the poet, thinker and artist Stefan Lazarević, was a period of renewed artistic development in Serbia. Stefan Lazarević himself was a poet, writing one of the major medieval Serbian literary works, Slovo ljubve ('The word of love') and one of the largest libraries in the Balkans at that period.

Economic stability

Apart from political stability as a result of Stefan's ability to keep a distance from both the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary, stability was also helped by the very rich silver mines, Srebrenica and Novo Brdo, some of the wealthiest in Europe at that time. Belgrade, at that time became one of the largest cities in Europe, numbering over 100,000 people. The rule and deeds of despot Stefan Lazarević were described by his contemporary, the learned writer Constantine of Kostenets, who wrote the "Life of Despot Stefan Lazarević" (c. 1430).[7]

First reign

_-_pano.JPG.webp)

As despot Stefan had no children of his own, already in 1426 he bequeathed the Despotate to his nephew, Đurađ Branković, who succeeded him upon his death on July 19, 1427. Already the second most important figure in the Despotate for the last 15 years, he was confirmed as despot by the Byzantine emperor John VIII Palaeologus in 1429.[8]

As an immediate result of Stefan's death, Serbia had to return Belgrade to the Kingdom of Hungary, but kept Mačva. As the southern wealthy cities (like Novo Brdo) were too close to the Ottomans to be declared new capitals, Đurađ decided to build a new one, the magnificent fortress of Smederevo on the Danube, close to the border of the Kingdom of Hungary. Constructed 1428–30, Smederevo was a source of many future misinterpretations of the history, especially concerning Đurađ's wife Jerina. With Jerina's Greek nationality and the influence her brothers had with the new despot, people began to dislike her, and attributed to her many vicious and evil characteristics, including building Smederevo for capricious reasons. In folk poetry she's been dubbed Prokleta Jerina (the Damned Jerina), but none of this has been confirmed by actual historical sources.

Immediately after becoming the ruler of Serbia, in the summer of 1427, Đurađ was faced with the challenge of an Ottoman invasion. The Ottomans occupied Kruševac and Niš, the Dubočica region including Leskovac, and most of the Toplica region. They withdrew after unsuccessfully besieging Novo Brdo for several months.[8]

King Tvrtko II of Bosnia came into conflict with the Bosnian noble family of Zlatonosovići in November 1430, over alleged cooperation between Vukašin Zlatonosović and the Serbian Despotate. This conflict ended with the death of Vukašin and the complete annihilation of the Zlatonosović family, but directly led into another conflict with Serbia itself. In the spring of 1433, Despot Đurađ annexed parts of Usora, together with the trade outpost Zvonik (Zvornik) and fortress Teočak.[9]

Đurađ married his daughter Katarina to Ulrich II of Celje in 1433, a close cousin of the Hungarian Queen, in an effort to secure better relations with Serbia's northern neighbor. His other daughter Mara, he had to marry to Sultan Murad II. This marriage was arranged in 1433, but Đurađ delayed it until 1435 when the Ottomans threatened him with invasion. After the marriage took place, Murad swore to continue the peace between the Ottoman Empire and Serbia.

However, this oath would be broken two years later. The Ottoman Empire invaded and started pillaging inside Serbia's borders in 1437. Đurađ negotiated an unfavorable peace with the Sultan by giving him the town of Braničevo. In 1438 the Sultan attacked again. This time, the Despot had to let them seize Ždrelo and Višesav: the peace that followed was not longer than the previous one.[10]

Temporary Ottoman occupation

In 1439 the Ottoman army, headed by the sultan Murad II himself, again attacked and sacked Serbia. Despot Đurađ fled to Hungary in May 1439, leaving his son Grgur Branković and Jerina's brother Thomas Kantakouzenos to defend Smederevo.[11] After three months of siege, Smederevo fell on August 18, 1439, while Novo Brdo resisted conquest for two entire years, falling on June 27, 1441. At that point the only free part of the Despotate that remained was Zeta. The latter, however, was soon attacked by the Venetians and by Voivode Stefan Vukčić Kosača. The last of Đurađ's cities in the region were conquered in March 1442.

The first Ottoman governor of Serbia was Ishak-Beg, who in 1443 was replaced by Isa-Beg Isaković.

Đurađ Branković restored

In Hungary, Đurađ Branković managed to talk Hungarian leaders into expelling the Ottomans, so a broad Christian coalition of Hungarians (under John Hunyadi), Serbs (under Despot Đurađ) and Romanians (under Vlad II Dracul) advanced into Serbia and Bulgaria in September 1443. The large Christian army that crossed the Danube in early autumn of 1443 was made up of around 25,000 soldiers from Hungary and Poland, over 8,000 Serbian cavalry and foot soldiers, and 700 Bosnian horsemen.[12] Serbia was fully restored by the Peace of Szeged on August 15, 1444. Its borders were the same as before 1437, with the exception of the southern part of Zeta, which remained under Venice, and fort Golubac, which was returned to Serbia even though it was lost much earlier, in 1427.

King Tomaš of Bosnia started another war with Despot Đurađ in 1446 and managed to take Srebrenica. However, in September 1448, the Bosnians were defeated by a Serbian army led by Thomas Kantakouzenos, who reconquered Srebrenica and also took Višegrad.[13]

The difficulty Despot Đurađ had in maintaining balance between two strong powers can be illustrated by the fact that in 1447–48 despot Đurađ provided funds to the Byzantines to repair the city walls of Constantinople, but being officially an Ottoman vassal, he had to send a thousand soldiers to help Sultan Mehmed II conquer Constantinople in May 1453.[14]

The new Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed II, who would later be called the Conqueror, returned the regions of Toplica and Dubočica to Serbia in 1451 as a token of good will.[15][8] On that occasion, Mehmed II and Đurađ negotiated the prolonging of their peace treaty.

Without formally declaring an end to the peace treaty, Sultan Mehmed II invaded Serbia in mid-July 1454. Much of central Serbia fell, but the capital was well-prepared and the Ottomans, upon hearing that Hunyadi would cross the Danube to reinforce the Serbs, soon lifted their siege of Smederevo. The Sultan retreated back to Sofia with loot and slaves, leaving most of his army at Kruševac. A smaller Serbian army under Voivode Nikola Skobaljić, which was in Dubočica, cut off from the north, defeated an Ottoman army near Leskovac on September 24, while the main army under Đurađ Branković, together with Hungarian force led by Hunyadi, crushed the Ottomans at Kruševac, capturing their commander, Firuz-bey.[16][14]

But these successes only bought little time. Nikola Skobaljić's resistance, which due to his army's low numbers came to be respected by the Turks themselves, was crushed by another Ottoman force on November 16 and he was executed. In the early spring of 1455, the Sultan continued his invasion of Serbia. This time, the Ottomans focused on taking southern Serbia first. Novo Brdo was besieged with heavy cannons and fell on June 1, 1455, after forty days of resistance.[17][18] The rest of southern Serbia was occupied soon after that. At the same time, Despot Đurađ was trying to convince the Hungarians to launch another crusade, but returned empty-handed to Smederevo. In early 1456, he accepted a peace treaty with the Sultan, and southern Serbia remained in Ottoman hands.

A few months after the peace treaty, the Ottoman Empire attacked again. Both Smederevo and Belgrade, which were the primary target of the Turks, successfully resisted, but the countryside was devastated even further. Despot Đurađ Branković died on December 24, 1456.[19][18]

Lazar Branković

Despot Lazar Branković, the only one of Đurađ's sons not to be blinded by the Ottomans, succeeded his father. Sensing that Serbia is too weak to defeat a future Ottoman incursion on the battlefield, he managed to make a deal with sultan Mehmed II on January 15, 1457. According to this deal, he was granted back most of his father's lands and a promise that Serbia will not be disturbed by the Ottomans until Lazar's death. Lazar in turn had to pay a tribute, which was reduced because he no longer had the rich mines of Novo Brdo. Temporarily relieved of the southern threat, Lazar turned to the north and Hungarian internal battles, which he joined on the side of King Ladislaus, managing to capture the town of Kovin and several other towns on the left bank of the Danube in 1457.[20][18]

Immediately after death of their mother Jerina on May 3, 1457, the younger generation of the Branković family broke out in a conflict of succession. Seeking rights for his bastard son Vuk, blind Grgur Branković fled to the Ottoman Empire, together with Mara and Thomas Kantakouzenos. Lazar's brother, blind Stefan Branković, took his side and stayed with him. Despot Lazar suddenly died on January 20, 1458.[21][18]

Regency and Stefan Branković

As despot Lazar Branković had no sons, a three-member regency was formed after his death. It included Lazar's brother, the blind Stefan Branković, Lazar's widow Helena Palaiologina and Grand Duke Mihailo Anđelović.[22][18] Mihailo Anđelović, whose brother was the Ottoman Grand Vizier Mahmud-pasha Anđelović, began to plot with the Ottomans behind the backs of Stefan and Helena. In March, he brought a small detachment of Ottoman soldiers into Smederevo to reinforce his own bid for the Despotate. But the soldiers unexpectedly raised the Ottoman flag on the ramparts and started shouting the Sultan's name. The enraged citizens of Smederevo rose up against Anđelović on March 31, taking him prisoner and capturing or killing most of the Ottoman detachment.[23] Stefan Branković, who was proclaimed the new Despot, together with Helena Palaiologina, took control of Smederevo and the Despotate.

During the chaos that surrounded Lazar's death and the split in the provisional regency, King Stjepan Tomaš of Bosnia attacked the Despotate's holdings west of the Drina river and conquered most of them, leaving only Teočak in the Despotate's hands. Mihail Silagyi likewise seized most of Lazar's towns north of the Danube. Immediately after Mihailo Anđelović's failed coup, the Ottomans began another invasion of Serbia. Although they would not make any significant territorial gains until 1459, this was the beginning of the end for the Serbian Despotate. Stefan Branković ruled until 8 April 1459, when he was overthrown by a plot between Helena Palaiologina and King Tomaš, whose son briefly ruled as the new Despot.[24][25]

Stjepan Tomašević and fall of the Despotate

Stjepan Tomašević lost two countries to the Ottomans: Serbia in 1459 and Bosnia in 1463. His appointment as new despot was highly unpopular but pushed hard by his father, King Stjepan Tomaš of Bosnia. By this time Serbia was reduced to only a strip of land along the Danube. Sultan Mehmed II decided to conquer Serbia completely and arrived at Smederevo; the new ruler did not even try to defend the city. After negotiations, Bosnians were allowed to leave the city and Serbia was officially conquered by Turks on June 20, 1459.

Despotate in exile

In 1404 Hungarian King Sigismund lend parts of Syrmia, Banat and Bačka to Serbian Despot Stefan Lazarević for governing, later succeeded by Đurađ Branković. After the Ottoman Empire conquered Serbian Despotate in 1459, the Hungarian rulers renewed the legacy of Despots to the House of Branković in exile, later to the noble family of Berislavići Grabarski, who continued to govern most of Syrmia until the Ottoman conquest but territory has been in theory still under administration of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. The residence of the despots was Kupinik (modern Kupinovo). The Despots from the Branković dynasty were: Vuk Grgurević-Branković (1471–1485), Đorđe Branković (1486–1496) and Jovan Branković (1496–1502).[26][27]

Last titular despots were: Ivaniš Berislavić (1504–1514), Stjepan Berislavić (1520–1535), Radič Božić (1527–1528, Zapolya faction's pretender), and Pavle Bakić (1537).

State administration

In the Serbian Despotate, there were several noble offices with important duties and roles in the state's central administration, under the Despot as the monarch and chief authority.

- Grand Logothete (Велики Логотет/Veliki Logotet): a title originally used by the Byzantine Empire, adopted by the old Kingdom of Serbia, and retained by the Despotate. The Grand Logothete was the head of the Despot's chancellery, responsible for overseeing the central administration. The Grand Logothete was also the only person, other than the Despot and the Serbian Patriarch, to have certain jurisdictions over church matters.[28][29]

- Luka

- Bogdan

- Voihna

- Manojlo

- Bogdan

- Todor

- Stefan Ratković (1457–59)

- Grand Voivode (Велики Војвода/Veliki Vojvoda): the second highest-ranking military commander in the state, under the Despot himself but with more power and prestige than ordinary Voivodes.

- Radoslav Mihaljević

- Dmitar Krajković

- Mihailo Anđelović (1456–58)

- Marko Altomanović

- Grand Čelnik (Велики Челник/Veliki Čelnik): a title with wide-ranging competencies in judicial and other civilian matters – executing the ruler's decrees and representing the ruler in events such as settling territorial disputes between estates. The title of the Grand Čelnik was roughly equivalent to the Western European title of Comes Palatinus.

- Vuk Kuvet

- Hrebeljan

- Radič (fl. 1428–1433)

- Mihailo Anđelović (c. 1445)

- Đurađ Golemović

- Protovestiar (Протовестијар/Protovestijar): another Byzantine court title (protovestiarios) adopted by the old Kingdom of Serbia. The Protovestiar was responsible for state finances, including supervision of revenues and expenses and fiscal policy. After the first fall and liberation of Serbia in 1444, the title of Protovestiar disappeared and his role was taken over by the Treasurer (Serbian: Ризничар/Rizničar) or Čelnik riznički,[30] a title previously associated with the management of the ruler's personal treasury.

- Ivan (fl. 1402)

- Bogdan (fl. 1407–13)

- Nikola Rodop (fl. 1435)

- Paskoje Sorkočević (after 1444)

- Radoslav (after 1444)

Territorial organization

In 1410, Despot Stefan Lazarević enacted an administrative reform dividing the territory of the Despotate into districts. A district was called a Vlast (Serbian Cyrillic: Власт), and each Vlast was governed in the Despot's name by a Voivode. This reform, made necessary by the increasing threat of Turkish invasion, gave those Voivodes an authority over both civilian and military matters in their respective districts.[6] The Vlasts were retained by the Despotate until its fall.

Documents have been preserved about the Vlasts in Smederevo, Novo Brdo, Nekudim, Ostrovica, Golubac, Borač, Petrus, Lepenica, Kruševac, Ždrelo; west of the Drina, there were four Vlasts: Teočak, Tišnica, Zvonik and Srebrenica. After its incorporation into the Serbian Despotate in 1421, Zeta was organized as a single large Vlast. with its Voivode seated in Bar, later moving to Podgorica (1444) and finally Medun.[31][32]

Next to nothing has been preserved about the number and size of other Vlasts within the Despotate.

Rulers of the Serbian Despotate

| Name | Reign | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

(1374–1427) |

August, 1402 – July 19, 1427 | Lazarević dynasty | |

.jpg.webp) (1375–1456) |

July 19, 1427 – August 18, 1439 | Branković dynasty | |

.jpg.webp) (1416–59) |

May, 1439 – August 18, 1439 | co-regent for Đurađ | |

| Toma Kantakuzin | May, 1439 – August 18, 1439 | co-regent for Đurađ | |

| Ishak-Beg (d. 1443) | 1439–1443 | Ottoman governor | |

| Isa-Beg | 1443 – June 12, 1444 | Ottoman governor | |

| Đurađ Branković (1375–1456) |

June 12, 1444 – December 24, 1456 | restored | |

.jpg.webp) (1421–58) |

December 24, 1456 – January 19, 1458 | Branković dynasty | |

.jpg.webp) (1420–76) |

January 19, 1458 – March 21, 1459 | co-regent to March 1458 | |

| Mihailo Anđelović (d. 1464) | January 19, 1458 – March, 1458 | co-regent | |

| Jelena Paleolog (1432–73) | January 19, 1458 – March, 1458 | co-regent | |

|

March 21, 1459 – June 20, 1459 | Kotromanić dynasty | |

| Titular rulers of the Serbian Despotate in exile | |||

(1438–85) |

1471 – April 16, 1485 | Branković dynasty | |

(1461–1516) |

February, 1486 – July, 1497 | Branković dynasty | |

(1462–1502) |

1492 – December 10, 1502 | Branković dynasty | |

| Ivaniš Berislavić (d. 1514) |

1504 – January, 1514 | Berislavići Grabarski | |

| Stefan Berislavić (1504–35) |

1520–1535 | Berislavići Grabarski | |

| Radič Božić (d. 1528) |

June 29, 1527 – September, 1528 | ||

| Pavle Bakić (d. 1537) |

September 20, 1537 – October 9, 1537 | Bakić noble family | |

Citations

- Jireček 1918, pp. 263–264.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 89.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 91.

- Fine 1994, pp. 507–508.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 92.

- Fine 1994, p. 522.

- Radošević 1986, pp. 445–451.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 103.

- Mrgić-Radojčić 2004, p. 60.

- Ćirković 2004, pp. 103, 115.

- Ćirković 2004, pp. 103–104.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 104.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 106.

- Ćirković 2004, pp. 106–107.

- Fine 1994, p. 530.

- Fine 1994, pp. 568–569.

- Fine 1994, p. 569.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 107.

- Fine 1994, pp. 569–570.

- Fine 1994, pp. 571–572.

- Fine 1994, p. 572.

- Fine 1994, pp. 572–573.

- Fine 1994, p. 573.

- Fine 1994, pp. 574–575.

- Ćirković 2004, pp. 107–108.

- Ćirković 2004, pp. 101, 116, 139.

- Krstić 2017, pp. 151–153.

- Fine 1994, pp. 313, 624.

- Janićijević 1998, p. 589.

- Jireček 1918, p. 273.

- Fine 1994, pp. 516–517, 534.

- Ćirković 2004, pp. 92–93.

Genern and cited references

- Andrić, Stanko (2016). "Saint John Capistran and Despot George Branković: An Impossible Compromise". Byzantinoslavica. 74 (1–2): 202–227.

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme. ISBN 9782825119587.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St. Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895-1526. London & New York: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781850439776.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472082604.

- Hupchick, Dennis P. (2002). The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. New York: Palgrave. ISBN 9780312299132.

- Isailović, Neven (2016). "Living by the Border: South Slavic Marcher Lords in the Late Medieval Balkans (13th–15th Centuries)". Banatica. 26 (2): 105–117.

- Isailović, Neven G.; Krstić, Aleksandar R. (2015). "Serbian Language and Cyrillic Script as a Means of Diplomatic Literacy in South Eastern Europe in 15th and 16th Centuries". Literacy Experiences concerning Medieval and Early Modern Transylvania. Cluj-Napoca: George Bariţiu Institute of History. pp. 185–195.

- Ivanović, Miloš (2016). "Foreigners in the Service of Despot Đurađ Branković on Serbian territory". Banatica. 26 (2): 257–268.

- Ivanović, Miloš (2018). "The Nobility of the Despotate of Serbia between Ottoman Empire and Hungary (1457-1459)". Secular Power and Sacral Authority in Medieval East-Central Europe. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 167–177. ISBN 9789462981669.

- Ivanović, Miloš (2019). "Militarization of the Serbian State under Ottoman Pressure". Hungarian Historical Review. 8 (2): 390–410.

- Ivanović, Miloš; Isailović, Neven (2015). "The Danube in Serbian-Hungarian Relations in the 14th and 15th Centuries". Tibiscvm: Istorie–Arheologie. 5: 377–393.

- Ivić, Pavle, ed. (1995). The History of Serbian Culture. Edgware: Porthill Publishers. ISBN 9781870732314.

- Janićijević, Jovan, ed. (1998). The Cultural Treasury of Serbia. Belgrade: Idea, Vojnoizdavački zavod, Markt system. ISBN 9788675470397.

- Jireček, Constantin (1918). Geschichte der Serben. Vol. 2. Gotha: Perthes.

- Krstić, Aleksandar R. (2017). "Which Realm will You Opt for? – The Serbian Nobility Between the Ottomans and the Hungarians in the 15th Century". State and Society in the Balkans Before and After Establishment of Ottoman Rule. Belgrade: Institute of History, Yunus Emre Enstitüsü Turkish Cultural Centre. pp. 129–163. ISBN 9788677431259.

- Krstić, Aleksandar R. (2019). "Familiares of the Serbian despots in and from the territory of Banat (1411-1458)". Politics and Society in the Central and South-Eastern Europe (13th-16th centuries). Cluj-Napoca: Editura Mega. pp. 93–109.

- Miller, William (1923). "The Balkan States, II: The Turkish Conquest (1355-1483)". The Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. 4. Cambridge: University Press. pp. 552–593.

- Mrgić-Radojčić, Jelena (2004). "Rethinking the Territorial Development of the Medieval Bosnian State". Историјски часопис. 51: 43–64.

- Nikolić, Maja (2008). "The Byzantine Historiography on the State of Serbian Despots" (PDF). Зборник радова Византолошког института (in French). 45: 279–288.

- Orbini, Mauro (1601). Il Regno de gli Slavi hoggi corrottamente detti Schiavoni. Pesaro: Apresso Girolamo Concordia.

- Орбин, Мавро (1968). Краљевство Словена. Београд: Српска књижевна задруга.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Paizi-Apostolopoulou, Machi (2012). "Appealing to the Authority of a Learned Patriarch: New Evidence on Gennadios Scholarios' Responses to the Questions of George Branković". The Historical Review. 9: 95–116.

- Radošević, Ninoslava (1986). "Laudes Serbiae: The Life of Despot Stephan Lazarević by Constantine the Philosopher". Зборник радова Византолошког института (in French). 24–25: 445–451.

- Samardžić, Radovan; Duškov, Milan, eds. (1993). Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies. ISBN 9788675830153.

- Sedlar, Jean W. (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000–1500. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295800646.

- Soulis, George Christos (1984). The Serbs and Byzantium during the reign of Tsar Stephen Dušan (1331–1355) and his successors. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Library and Collection. ISBN 9780884021377.

- Spremić, Momčilo (2004). "La famille serbe des Branković - considérations généalogiques et héraldiques" (PDF). Зборник радова Византолошког института (in French). 41: 441–452.

- Spremić, Momčilo (2014). "Le Despote Stefan Lazarević et Sieur Djuradj Branković" (PDF). Balcanica (45): 145–163. doi:10.2298/BALC1445145S.

- Stanković, Vlada, ed. (2016). The Balkans and the Byzantine World before and after the Captures of Constantinople, 1204 and 1453. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. ISBN 9781498513265.

External links

Media related to Serbian Despotate at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Serbian Despotate at Wikimedia Commons