Reichsbank

The Reichsbank (German: [ˈʁaɪçsˌbank] ⓘ; lit. 'Bank of the Reich') was the central bank of the German Reich from its establishment in 1876 until liquidation in 1945.[1]

Reichsbank at Jägerstraße, photographed in 1933 | |

| Headquarters | Berlin |

|---|---|

| Established | 1 January 1876 |

| Ownership | Government owned |

| Präsident der Reichsbank | See list |

| Central bank of | German Empire Weimar Republic Nazi Germany |

| Currency | Reichsmark |

| Succeeded by | Bank deutscher Länder (West) Deutsche Notenbank (East) |

History until 1933

The Reichsbank was founded on 1 January 1876, shortly after the establishment of the German Empire in 1871. It was the central bank of Prussia, under the close control of the Reich government.[3] Its first president was Hermann von Dechend. Before unification in 1871, Germany had 31 central banks – the Notenbanken ("note banks"). Each of the independent states issued their own money. In 1870, a law was passed that forbade the formation of further central banks. In 1874, a draft banking law was introduced in the Reichstag, the federal legislature of the German Reich. After several changes and compromises, the law was passed in 1875. Despite the creation of the Reichsbank, however, four of the Notenbanken – Baden, Bavaria, Saxony and Württemberg – continued to exist until 1914 .

The Reichsbank experienced both stable and volatile periods. Until World War I, the Reichsbank produced a very stable currency called the Goldmark, but at the outbreak of WWI the link between the mark and gold was abandoned, resulting in the Papiermark. The expenses of the war caused inflationary pressure and the mark started to decrease in value . The defeat of Imperial Germany in 1918, the economic burden caused by the payment of war reparations to the Allies, and the social unrest in the early years culminated in the German hyperinflation of 1922–23.

Economic reforms, such as the issue of a new provisional currency – the Rentenmark – and the 1924 Dawes Plan, stabilised German monetary development and thus the economic outlook of the Weimar Republic. One of the key reforms caused by the Dawes Plan was the establishment of the Reichsbank as an institution independent of the Reich government. On 30 August 1924, the Reichsbank began issuing the Reichsmark, which served as the German currency until 1948.

Nazi period

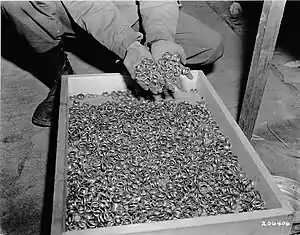

The seizure and consolidation of power by the Nazis during the years of the Third Reich also greatly affected the Reichsbank. A 1937 law re-established the Reich Government's control of the Reichsbank, and in 1939, the Reichsbank was renamed the Deutsche Reichsbank (“Bank of the German Reich”, lit.: “Bank of the German Realm”) and placed under the direct control of Adolf Hitler, with Walther Funk as the last president of the Reichsbank, from 1939 to 1945.[4] The bank benefited by the theft of the property of numerous governments invaded by the Germans, especially their gold reserves and much personal property of the Third Reich's many victims, especially the Jews. Personal possessions such as gold wedding rings were confiscated from prisoners, and gold teeth torn from dead bodies, and after cleaning, were deposited in the bank under the false-name Max Heiliger accounts, and melted down as bullion.

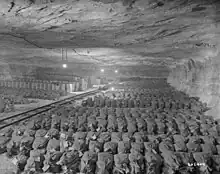

The defeat of Nazi Germany in May 1945 resulted in the dissolution of the Reichsbank, along with other Reich ministries and institutions. The explanation of the disappearance of the Reichsbank reserves in 1945 was uncovered by Bill Stanley Moss and Andrew Kennedy, in post-war Germany. In April and May 1945, the remaining reserves of the Reichsbank – gold (730 bars), cash (6 large sacks), and precious stones and metals such as platinum (25 sealed boxes) – were dispatched by Walther Funk to be buried on the Klausenhof Mountain at Einsiedl in Bavaria, where the final German resistance was to be concentrated. Similarly, the Abwehr cash reserves were hidden nearby in Garmisch-Partenkirchen. Shortly after the American forces overran the area, the reserves and money disappeared.[5] Funk would be tried and convicted of war crimes at the Nuremberg trials, not least for receiving money and goods stolen from Jewish and other victims of the Nazi concentration camps. Gold teeth extracted from the mouths of victims were found in 1945 in the vaults of the bank in Berlin.

The Allied occupation authorities (in the West – the United Kingdom, France and the United States; in the East – the Soviet Union) became responsible for German monetary policy in the immediate postwar years. In this role, the Allies continued to issue Reichsmarks (and Allied military marks) as the German banking system was gradually restored. In 1948, the Reichsmark ceased to exist owing to the introduction of the Deutsche Mark in the West and the East German mark in the East. In West Germany, monetary policy was taken over by the Bank deutscher Länder (Bank of the German States) and later by the Deutsche Bundesbank. In East Germany, this role was assumed by the Deutsche Notenbank (later renamed as the Staatsbank der DDR (State Bank of the German Democratic Republic).

Branches

In Prussia, the Reichsbank kept the branches it inherited from the Bank of Prussia, including buildings it had purchased from others (e.g. the palace erected by David Schindelmeißer in Königsberg, acquired in 1843) and those it had built for itself (e.g. in Bromberg in 1864). Elsewhere, it did not take over the properties of banks whose monetary role it replaced, and erected new branch buildings instead. By the end of the 19th century, it had newly built branches in most of Germany's significant cities. In some cases, these branches were replaced by more modern ones in the interwar period.

The Reichsbank employed a number of specialized architects for branch design, including the prolific Max Hasak and Julius Emmerich from the 1880s to the early 1900s, Havestadt & Contag in the 1890s and early 1900s, Curjel and Moser in the 1900s, Julius Habicht and Hermann Stiller in the 1900s and 1910s, Philipp Nitze in the 1910s and 1920s, and Heinrich Wolff in the 1920s and 1930s.

Due to Germany's territorial losses following World War I, the former Reichsbank branches in what became the Second Polish Republic were taken over by Bank Polski, and the one in the Free City of Danzig became the Bank of Danzig. During World War II, a number of branches were destroyed and not subsequently rebuilt. The one in Munich, whose construction had started in 1938 on the site of the former Herzog-Max-Palais demolished that year, was only completed in 1951.[6] Following the disappearance of the Reichsbank in 1945, a number of its former branches were taken over by its successor entities, namely the Deutsche Bundesbank in West Germany, the Staatsbank der DDR in East Germany, and the National Bank of Poland in Poland; some in East Germany were demolished later on, such as the Chemnitz branch in 1964.[7] Many other branches have been repurposed for other uses over the years, such as the Bucerius Kunst Forum in Hamburg or the Dommuseum Ottonianum in Magdeburg.

The addresses indicated below are the latest ones, which sometimes differ from original addresses due to street renaming and/or renumbering.

.JPG.webp) Aachen branch, Theaterstrasse 17 (arch. Hasak), completed 1889

Aachen branch, Theaterstrasse 17 (arch. Hasak), completed 1889 Brandenburg branch, Neustädter Markt 10 (arch. Hasak), completed 1902

Brandenburg branch, Neustädter Markt 10 (arch. Hasak), completed 1902

![Bromberg (now Bydgoszcz) branch, Jagiellońska street 8 (arch. Hermann Cuno [de]), completed 1864](../I/Bdg_ulJagiellonska_4_10-2013.jpg.webp)

Cologne branch, Unter Sachsenhausen 1-3 (arch. Hasak), at completion in 1896

Cologne branch, Unter Sachsenhausen 1-3 (arch. Hasak), at completion in 1896.jpg.webp) The same building in 2009, following damage in World War II[9]

The same building in 2009, following damage in World War II[9]![Danzig (now Gdańsk) branch [de], Karrenwall 10 (arch. Hasak), completed ca. 1904](../I/Bank_of_Danzig.JPG.webp)

The same building in 2010

The same building in 2010![Darmstadt branch [de], Kasinostraße 5 (arch. Curjel and Moser), completed 1904](../I/Darmstadt-Ehem-Reichsbank.jpg.webp) Darmstadt branch, Kasinostraße 5 (arch. Curjel and Moser), completed 1904

Darmstadt branch, Kasinostraße 5 (arch. Curjel and Moser), completed 1904![Düsseldorf branch [de], Heinrich-Heine-Allee 8/9 (arch. Emmerich), completed 1894](../I/Ehemaliges_Reichsbankgeb%C3%A4ude%252C_Fassade%252C_Heinrich-Heine-Allee_8-9%252C_D%C3%BCsseldorf-Altstadt.jpg.webp) Düsseldorf branch, Heinrich-Heine-Allee 8/9 (arch. Emmerich), completed 1894

Düsseldorf branch, Heinrich-Heine-Allee 8/9 (arch. Emmerich), completed 1894![Dresden branch [de], St. Petersburger Strasse 2 (arch. Wolff), completed 1930](../I/Ehemalige_Reichsbank_Dresden_01.jpg.webp) Dresden branch, St. Petersburger Strasse 2 (arch. Wolff), completed 1930

Dresden branch, St. Petersburger Strasse 2 (arch. Wolff), completed 1930 Duisburg branch, Düsseldorfer Strasse 21 (arch. Stiller), completed 1897

Duisburg branch, Düsseldorfer Strasse 21 (arch. Stiller), completed 1897 Elberfeld branch, Bankstrasse 23 (arch. Hasak), completed 1892

Elberfeld branch, Bankstrasse 23 (arch. Hasak), completed 1892![Eisenach branch [de], Karl-Marx-Straße 53, completed 1905](../I/ESA_Karl-Marx-Str_53_Bild1.jpg.webp)

Werden, Essen branch, Wesselswerth 9, completed 1902[12]

Werden, Essen branch, Wesselswerth 9, completed 1902[12]

_jm59668.jpg.webp) Freiburg im Breisgau branch, Leopoldring 9 (arch. Hasak), completed 1902

Freiburg im Breisgau branch, Leopoldring 9 (arch. Hasak), completed 1902 Fulda branch, Rabanusstrasse 12 (arch. Hasak), completed 1902

Fulda branch, Rabanusstrasse 12 (arch. Hasak), completed 1902

![Hanover branch [de], Georgsplatz 5 (arch. Hasak, Havestadt & Contag), completed 1896](../I/Deutsche_Bundesbank_office_building_Georgsplatz_5_Hannover_Germany.jpg.webp) Hanover branch, Georgsplatz 5 (arch. Hasak, Havestadt & Contag), completed 1896

Hanover branch, Georgsplatz 5 (arch. Hasak, Havestadt & Contag), completed 1896 Hildesheim branch, Zingel 34 (arch. Hasak), completed 1897

Hildesheim branch, Zingel 34 (arch. Hasak), completed 1897 Hörde (Dortmund) branch, Penningskamp 7, completed 1909

Hörde (Dortmund) branch, Penningskamp 7, completed 1909 Karlsruhe branch, Herrenstrasse 30 (arch. Hasak, Havestadt & Contag), completed 1893

Karlsruhe branch, Herrenstrasse 30 (arch. Hasak, Havestadt & Contag), completed 1893

.jpg.webp) Kiel branch, Fleethörn 29 (early 20th century photograph)

Kiel branch, Fleethörn 29 (early 20th century photograph) Krefeld branch, Friedrichsplatz 20 (arch. Stiller), completed 1906

Krefeld branch, Friedrichsplatz 20 (arch. Stiller), completed 1906.JPG.webp) Königsberg (now Kaliningrad) branch, Grosser Domplatz, erected in the late 18th century, destroyed in World War II[17]

Königsberg (now Kaliningrad) branch, Grosser Domplatz, erected in the late 18th century, destroyed in World War II[17]![Leipzig branch [de], Petersstrasse 43 (arch. Hasak), completed 1887](../I/Musikschule_Johann_Sebastian_Bach_Leipzig_2010_cropped.jpg.webp)

![Lübeck new branch [de], Holstentorplatz 2 (arch. Wolff), completed 1936](../I/HL_Bundesbank_4_2013_5.JPG.webp) Lübeck new branch, Holstentorplatz 2 (arch. Wolff), completed 1936

Lübeck new branch, Holstentorplatz 2 (arch. Wolff), completed 1936![Magdeburg branch [de], Domplatz 15 (arch. Nitze), completed 1923](../I/Magdeburg_asv2022-08_img19_Dommuseum.jpg.webp)

Mainz branch, Kaiserstraße 52 (arch. Hasak, Havestadt & Contag), completed 1892

Mainz branch, Kaiserstraße 52 (arch. Hasak, Havestadt & Contag), completed 1892![Metz branch [fr], 10-12 avenue Foch (arch. Curjel et Moser), completed 1907](../I/Chambre_Commerce_Industrie_Moselle_-_Metz_(FR57)_-_2022-02-26_-_2.jpg.webp) Metz branch, 10-12 avenue Foch (arch. Curjel et Moser), completed 1907

Metz branch, 10-12 avenue Foch (arch. Curjel et Moser), completed 1907 Munich branch, Ludwigstrasse 13 (arch. Wolff, then Carl Sattler), completed 1951 for the Bayerische Landeszentralbank

Munich branch, Ludwigstrasse 13 (arch. Wolff, then Carl Sattler), completed 1951 for the Bayerische Landeszentralbank Münster branch, Domplatz 36 (arch. Hasak, Havestadt & Contag), completed 1894

Münster branch, Domplatz 36 (arch. Hasak, Havestadt & Contag), completed 1894![Siegen branch [de], Spandauer Straße 40 (arch. Habicht), completed 1911](../I/Siegen_Reichsbank.jpg.webp) Siegen branch, Spandauer Straße 40 (arch. Habicht), completed 1911

Siegen branch, Spandauer Straße 40 (arch. Habicht), completed 1911![Stuttgart branch, Marstallstrasse 3 (arch. Hans Herkommer [de] & Theodor Bulling), completed 1923](../I/Hauptverwaltung_Deutsche_Bundesbank_Stuttgart_01.jpg.webp)

Thorn (now Toruń) branch, Plac Mariana Rapackiego (arch. Habicht), completed 1906

Thorn (now Toruń) branch, Plac Mariana Rapackiego (arch. Habicht), completed 1906 Trier branch, Kochstrasse 13 (arch. Hasak), completed 1903

Trier branch, Kochstrasse 13 (arch. Hasak), completed 1903

Presidents

| No. | Picture | President of Reichsbank | Took office | Left office | Time in office |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hermann von Dechend (1814–1890) | 1876 | 1890 | 13–14 years | |

| 2 | Richard Koch (1834–1910) | 1890 | 1908 | 13–14 years | |

| 3 | Rudolf Havenstein (1857–1923) | 1908 | 11 November 1923 | 14–15 years | |

| 4 | Hjalmar Schacht (1877–1970) | 22 December 1923[21] (appointed Currency Commissioner on 12 November 1923)[22] | 6 March 1930 | 6 years | |

| 5 | Hans Luther (1879–1962) | 7 March 1930 | 17 March 1933 | 3 years | |

| (4) | Hjalmar Schacht (1877–1970) | 18 March 1933 | 19 January 1939 | 5 years | |

| 6 | Walther Funk (1890–1960) | 20 January 1939 | 8 May 1945 | 6 years |

See also

References

- Budzinski, Prof Dr Oliver. "Definition: Reichsbank". wirtschaftslexikon.gabler.de (in German). Retrieved 2020-01-06.

- "German Notes". 2018-01-06. Retrieved 2021-08-31.

- "168. The Reichsbank". chestofbooks.com. Retrieved 2021-08-31.

- Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Greenwich: Fawcett Publications, 1959. 360.

- Moss, W. Stanley, Gold Is Where You Hide It; What Happened to the Reichsbank Treasure?, Andre Deutsch 1959

- Thomas Müller. "Das Herzog-Max-Palais: Ein Abriss zugunsten der "Hauptstadt der Deutschen Kunst". Munich Art To Go.

- "Reichsbank – Hier ist ihr Geld sicher". chemnitz-gestern-heute.de.

- Jacek Kulesza (11 December 2015). "AC Hotel by Marriott powstanie w gmachu dawnego Banku Rzeszy". wyborcza.pl.

- Walter Buschmann and Alexander Kierdorf. "Bankenviertel Köln". Rheinische Industriekultur.

- "Reichsbankgebäude Eisenach". Architektur Bildarchiv.

- Adrian Sajko (13 August 2014). "Bank opuszcza zabytkowy budynek przy 1 Maja. Kupiec pilnie poszukiwany". info.elblag.pl.

- "Ehemalige Reichsbank". Essener Ruhrperlen.

- Gottfried Kiesow (December 2011). "Die Baukunst zwischen den Weltkriegen". Monumente.

- "LZB Landeszentralbank in Hessen, Frankfurt am Main". Jourdain & Müller Steinhauser Architekten.

- "Ehemalige Reichsbank". duisburg.de.

- "150 lat Katowic. Kocur dostał dwa lwy i wypalił fajkę pokoju". wyborcza.pl. 1 August 2015.

- "Königsberg (Pr.), Großer Domplatz, Reichsbank (Schindelmeißer-Haus)". Ostpreussen Bildarchiv.

- "Reichsbank-Gebäude Lübeck". Architektur Bildarchiv.

- "Die Reichsbank am Breiten Weg". Ottostadt Magdeburg.

- Iris Cramer and Sabine Muschler. "Architektur und Kunst: Deutsche Bundesbank Hauptverwaltung in Baden-Württemberg" (PDF). Deutsche Bundesbank.

- Marsh, David (1992). The Most Powerful Bank: Inside Germany's Bundesbank. New York: Times Books. p. 85. ISBN 0-8129-2158-5.

- Marsh, David (1992). The Most Powerful Bank: Inside Germany's Bundesbank. New York: Times Books. p. 84. ISBN 0-8129-2158-5.

External links

Media related to Reichsbank at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Reichsbank at Wikimedia Commons- Documents and clippings about Reichsbank in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

![Richard Koch [de]](../I/Richard_Koch_(Reichsbank%252C_Reclam_Universum).jpg.webp)