Devolution in the United Kingdom

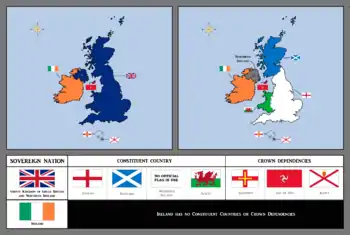

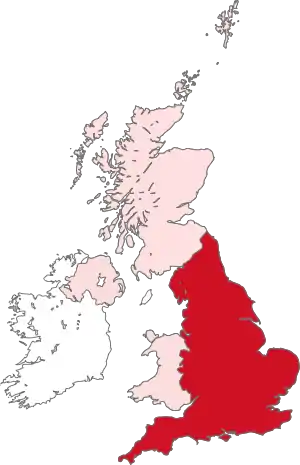

In the United Kingdom, devolution is the Parliament of the United Kingdom's statutory granting of a greater level of self-government to the Scottish Parliament, the Senedd (Welsh Parliament), the Northern Ireland Assembly and the London Assembly and to their associated executive bodies the Scottish Government, the Welsh Government, the Northern Ireland Executive and in England, the Greater London Authority and combined authorities.

| This article is part of a series on |

| Politics of the United Kingdom |

|---|

_(2022).svg.png.webp) |

|

Devolution differs from federalism in that the devolved powers of the subnational authority ultimately reside in central government, thus the state remains, de jure, a unitary state. Legislation creating devolved parliaments or assemblies can be repealed or amended by parliament in the same way as any statute.

Legislation passed following the EU membership referendum, including the United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020, undermines and restricts the authority of the devolved legislatures in both Scotland and Wales.[1]

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland was the first constituent of the UK to have a devolved administration.[lower-alpha 1] Home Rule came into effect for Northern Ireland in 1921, under the Government of Ireland Act 1920 ("Fourth Home Rule Act"). The Parliament of Northern Ireland established under that act was prorogued (the session ended) on 30 March 1972 owing to the destabilisation of Northern Ireland upon the onset of the Troubles in late 1960s. This followed escalating violence by state and paramilitary organisations following the suppression of civil rights demands by Northern Ireland Catholics.

The Northern Ireland Parliament was abolished by the Northern Ireland Constitution Act 1973, which received royal assent on 19 July 1973. A Northern Ireland Assembly was elected on 28 June 1973 and following the Sunningdale Agreement, a power-sharing Northern Ireland Executive was formed on 1 January 1974. This collapsed on 28 May 1974, due to the Ulster Workers' Council strike. The Troubles continued.

The Northern Ireland Constitutional Convention (1975–1976) and second Northern Ireland Assembly (1982–1986) were unsuccessful at restoring devolution. In the absence of devolution and power-sharing, the UK Government and Irish Government formally agreed to co-operate on security, justice and political progress in the Anglo-Irish Agreement, signed on 15 November 1985. More progress was made after the ceasefires by the Provisional IRA in 1994 and 1997.[2]

The 1998 Belfast Agreement (also known as the Good Friday Agreement), resulted in the creation of a new Northern Ireland Assembly, intended to bring together the two communities (nationalist and unionist) to govern Northern Ireland.[3] Additionally, renewed devolution in Northern Ireland was conditional on co-operation between the newly established Northern Ireland Executive and the Government of Ireland through a new all-Ireland body, the North/South Ministerial Council. A British–Irish Council covering the whole British Isles and a British–Irish Intergovernmental Conference (between the British and Irish Governments) were also established.

From 15 October 2002, the Northern Ireland Assembly was suspended due to a breakdown in the Northern Ireland peace process but, on 13 October 2006, the British and Irish governments announced the St Andrews Agreement, a 'road map' to restore devolution to Northern Ireland.[4] On 26 March 2007, Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) leader Ian Paisley met Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams for the first time and together announced that a devolved government would be returning to Northern Ireland.[5] The Executive was restored on 8 May 2007.[6] Several policing and justice powers were transferred to the Assembly on 12 April 2010.

The 2007–2011 Assembly (the third since the 1998 Agreement) was dissolved on 24 March 2011 in preparation for an election to be held on Thursday 5 May 2011, this being the first Assembly since the Good Friday Agreement to complete a full term.[7] The fifth Assembly convened in May 2016.[8] That assembly dissolved on 26 January 2017, and an election for a reduced Assembly was held on 2 March 2017 but this did not lead to formation of a new Executive due to the collapse of power-sharing. Power-sharing collapsed in Northern Ireland due to the Renewable Heat Incentive scandal. On 11 January 2020, after having been suspended for almost three years, the parties reconvened on the basis of an agreement proposed by the Irish and UK governments.[9] Elections were held for a seventh assembly in May 2022. Sinn Féin emerged as the largest party, followed by the Democratic Unionist Party.[10] The newly elected assembly met for the first time on 13 May 2022 and again on 30 May. However, at both these meetings, the DUP refused to assent to the election of a speaker[11] as part of a protest against the Northern Ireland Protocol, which meant that the assembly could not continue other business, including the appointment of a new Executive.[12] As of May 2023, the Assembly remains in abeyance.

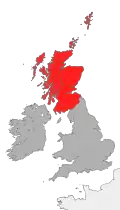

Scotland

The Acts of Union 1707 merged the Scottish and English Parliaments into a single Parliament of Great Britain. Ever since, individuals and organisations advocated the return of a Scottish Parliament. The drive for home rule for Scotland first took concrete shape in the 19th century, as demands for home rule in Ireland were met with similar (although not as widespread) demands in Scotland. The National Association for the Vindication of Scottish Rights was established in 1853, a body close to the Scottish Unionist Party and motivated by a desire to secure more focus on Scottish problems in response to what they felt was undue attention being focused on Ireland by the then Liberal government. In 1871, William Ewart Gladstone stated at a meeting held in Aberdeen that if Ireland was to be granted home rule, then the same should apply to Scotland. A Scottish home rule bill was presented to the Westminster Parliament in 1913 but the legislative process was interrupted by the First World War.

The demands for political change in the way in which Scotland was run changed dramatically in the 1920s when Scottish nationalists started to form various organisations. The Scots National League was formed in 1920 in favour of Scottish independence, and this movement was superseded in 1928 by the formation of the National Party of Scotland, which became the Scottish National Party (SNP) in 1934. At first the SNP sought only the establishment of a devolved Scottish assembly, but in 1942 they changed this to support all-out independence. This caused the resignation of John MacCormick from the SNP and he formed the Scottish Covenant Association. This body proved to be the biggest mover in favour of the formation of a Scottish assembly, collecting over two million signatures in the late 1940s and early 1950s and attracting support from across the political spectrum. However, without formal links to any of the political parties it withered, devolution and the establishment of an assembly were put on the political back burner.

Harold Wilson's Labour government set up a Royal Commission on the Constitution in 1969, which reported in 1973 to Edward Heath's Conservative government. The Commission recommended the formation of a devolved Scottish assembly, but was not implemented.

Support for the SNP reached 30% in the October 1974 general election, with 11 SNP MPs being elected. In 1978 the Labour government passed the Scotland Act which legislated for the establishment of a Scottish Assembly, provided the Scots voted for such in a referendum. However, the Labour Party was bitterly divided on the subject of devolution. An amendment to the Scotland Act that had been proposed by Labour MP George Cunningham, who shortly afterwards defected to the newly formed Social Democratic Party (SDP), required 40% of the total electorate to vote in favour of an assembly. Despite officially favouring it, considerable numbers of Labour members opposed the establishment of an assembly. This division contributed to only a narrow 'Yes' majority being obtained, and the failure to reach Cunningham's 40% threshold. The 18 years of Conservative government, under Margaret Thatcher and then John Major, saw strong resistance to any proposal for devolution for Scotland, and for Wales.

In response to Conservative dominance, in 1989 the Scottish Constitutional Convention was formed encompassing the Labour Party, Liberal Democrats and the Scottish Green Party, local authorities, and sections of "civic Scotland" like Scottish Trades Union Congress, the Small Business Federation and Church of Scotland and the other major churches in Scotland. Its purpose was to devise a scheme for the formation of a devolution settlement for Scotland. The SNP decided to withdraw as independence was not a constitutional option countenanced by the convention. The convention produced its final report in 1995.

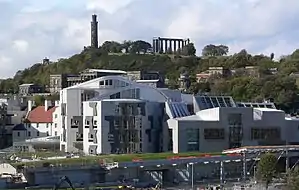

In May 1997, the Labour government of Tony Blair was elected with a promise of creating devolved institutions in Scotland. In late 1997, a referendum was held which resulted in a "yes" vote. The newly created Scottish Parliament (as a result of the Scotland Act 1998) has powers to make primary legislation in all areas of policy which are not expressly 'reserved' for the UK Government and parliament such as national defence and international affairs. Note that 76% of Scotland's revenue and 36% of its spending are 'reserved'.[13]

Devolution for Scotland was justified on the basis that it would make government more representative of the people of Scotland. It was argued that the population of Scotland felt detached from the Westminster government (largely because of the policies of the Conservative governments led by Margaret Thatcher and John Major). Critics however point out that the Scottish Parliament’s power is on most measures surpassed by the parliaments of regions or provinces within federations, where regional and national parliaments are each sovereign within their spheres of jurisdiction.[14][15]

A referendum on Scottish independence was held on 18 September 2014, with the referendum being defeated 55.3% (No) to 44.7% (Yes). In the 2015 general election the SNP won 56 of the 59 Scottish seats with 50% of all Scottish votes. This saw the SNP replace the Liberal Democrats as the third largest in the UK Parliament.

In the 2016 Scottish Parliament election the SNP fell two seats short of an overall majority with 63 seats but remained in government for a third term. The proportional electoral system used for Holyrood elections makes it very difficult for any party to gain a majority. The Scottish Conservatives won 31 seats and became the second largest party for the first time. Scottish Labour, down to 24 seats from 38, fell to third place. The Scottish Greens took 6 seats and overtook the Liberal Democrats who remained flat at 5 seats.

Following the 2016 referendum on EU membership, where Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to Remain and England and Wales voted to Leave (leading to a 52% Leave vote nationwide), the Scottish Parliament voted for a second independence referendum to be held once conditions of the UK's EU exit are known. Conservative Prime Minister Theresa May rejected this request citing a need to focus on EU exit negotiations. The SNP had advocated for another independence referendum to be held in 2020, but this was stopped by the Conservatives winning the majority of seats in the 2019 General Election. They were widely expected to include a second independence referendum in their manifesto for the 2021 Scottish Parliament election.[16] Senior SNP figures have said that a second independence referendum would be inevitable, should an SNP majority be elected to the Scottish Parliament in 2021 and some claimed this was going to happen by the end of 2021, though that hasn't been the case.[17]

The United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020 restricts and undermines the authority of the Scottish Parliament.[lower-alpha 2] Its primary purpose is to constrain the capacity of the devolved institutions to use their regulatory autonomy.[18] It restricts the ability of the Scottish government to make different economic or social choices from those made in Westminster.[1]

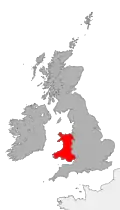

Wales

Following the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542, Wales was treated in legal terms as part of England. However, during the later part of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century the notion of a distinctive Welsh polity gained credence. In 1881 the Sunday Closing (Wales) Act 1881 was passed, the first such legislation exclusively concerned with Wales. The Central Welsh Board was established in 1896 to inspect the grammar schools set up under the Welsh Intermediate Education Act 1889, and a separate Welsh Department of the Board of Education was formed in 1907. The Agricultural Council for Wales was set up in 1912, and the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries had its own Welsh Office from 1919.

Despite the failure of popular political movements such as Cymru Fydd, a number of national institutions, such as the National Eisteddfod (1861), the Football Association of Wales (1876), the Welsh Rugby Union (1881), the University of Wales (Prifysgol Cymru) (1893), the National Library of Wales (Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru) (1911) and the Welsh Guards (Gwarchodlu Cymreig) (1915) were created. The campaign for disestablishment of the Anglican Church in Wales, achieved by the passage of the Welsh Church Act 1914, was also significant in the development of Welsh political consciousness. Plaid Cymru was formed in 1925.

An appointed Council for Wales and Monmouthshire was established in 1949 to "ensure the government is adequately informed of the impact of government activities on the general life of the people of Wales". The council had 27 members nominated by local authorities in Wales, the University of Wales, National Eisteddfod Council and the Welsh Tourist Board. A cross-party Parliament for Wales campaign in the early 1950s was supported by a number of Labour MPs, mainly from the more Welsh-speaking areas, together with the Liberal Party and Plaid Cymru. A post of Minister of Welsh Affairs was created in 1951 and the post of Secretary of State for Wales and the Welsh Office were established in 1964 leading to the abolition of the Council for Wales and Monmouthshire.

Labour's incremental embrace of a distinctive Welsh polity was arguably catalysed in 1966 when Plaid Cymru president Gwynfor Evans won the Carmarthen by-election. In response to the emergence of Plaid Cymru and the Scottish National Party (SNP) Harold Wilson's Labour Government set up the Royal Commission on the Constitution (the Kilbrandon Commission) to investigate the UK's constitutional arrangements in 1969. The 1974–1979 Labour government proposed a Welsh Assembly in parallel to its proposals for Scotland. These were rejected by voters in the 1979 referendum: 956,330 votes against, 243,048 for.

In May 1997, the Labour government of Tony Blair was elected with a promise of creating a devolved assembly in Wales; the referendum in 1997 resulted in a narrow "yes" vote. The turnout was 50.22% with 559,419 votes (50.3%) in favour and 552,698 (49.7%) against, a majority of 6,721 (0.6%). The National Assembly for Wales, as a consequence of the Government of Wales Act 1998, possesses the power to determine how the government budget for Wales is spent and administered. The 1998 Act was followed by the Government of Wales Act 2006 which created an executive body, the Welsh Government, separate from the legislature, the National Assembly for Wales. It also conferred on the National Assembly some limited legislative powers.

The 1997 devolution referendum was only narrowly passed with the majority of voters in the former industrial areas of the South Wales Valleys and the Welsh-speaking heartlands of West Wales and North Wales voting for devolution and the majority of voters in all the counties near England, plus Cardiff and Pembrokeshire rejecting devolution. However, all recent opinion polls indicate an increasing level of support for further devolution, with support for some tax varying powers now commanding a majority, and diminishing support for the abolition of the Assembly.

The 2011 Welsh devolution referendum saw a majority of 21 local authority constituencies to 1 voting in favour of more legislative powers being transferred from the UK parliament in Westminster to the Welsh Assembly. The turnout in Wales was 35.4% with 517,132 votes (63.49%) in favour and 297,380 (36.51%) against increased legislative power.

A Commission on Devolution in Wales was set up in October 2011 to consider further devolution of powers from London. The commission issued a report on the devolution of fiscal powers in November 2012 and a report on the devolution of legislative powers in March 2014. The fiscal recommendations formed the basis of the Wales Act 2014, while the majority of the legislative recommendations were put into law by the Wales Act 2017.

On 6 May 2020, the National Assembly was renamed "Senedd Cymru" or "the Welsh Parliament" with the "Senedd" as its common name in both languages.[26]

The devolved competence of the Welsh Government, as the Scottish Government, is restricted and undermined by the United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020.[1]

England

National

England is the only country of the United Kingdom to not have a devolved Parliament or Assembly and English affairs are decided by the Westminster Parliament.

Parliament

There have been proposals for the establishment of a single devolved English parliament to govern the affairs of England as a whole. This has been supported by groups such as English Commonwealth, the English Democrats, and Campaign for an English Parliament, as well as the Scottish National Party and Plaid Cymru who have both expressed support for greater autonomy for all four nations while ultimately striving for a dissolution of the Union. Without its own devolved Parliament, England continues to be governed and legislated for by the UK Government and UK Parliament, which gives rise to the West Lothian question. The question concerns the fact that, on devolved matters, Scottish MPs continue to help make laws that apply to England alone, although no English MPs can make laws on those same matters for Scotland. Since the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, there has been a wider debate about the UK adopting a federal system with each of the four Home Nations having its own, equal devolved legislatures and law-making powers.[27]

In the first five years of devolution for Scotland and Wales, support in England for the establishment of an English parliament was low at between 16 and 19 per cent.[28] While a 2007 opinion poll found that 61 per cent would support such a parliament being established,[29] a report based on the British Social Attitudes Survey published in December 2010 suggests that only 29 per cent of people in England support the establishment of an English parliament, though this figure has risen from 17 per cent in 2007.[30] John Curtice argues that tentative signs of increased support for an English parliament might represent "a form of English nationalism...beginning to emerge among the general public".[31] Krishan Kumar, however, notes that support for measures to ensure that only English MPs can vote on legislation that applies only to England is generally higher than that for the establishment of an English parliament, although support for both varies depending on the timing of the opinion poll and the wording of the question.[32]

In September 2011 it was announced that the British government was to set up a commission to examine the West Lothian question.[33] In January 2012 it was announced that this six-member commission would be named the Commission on the consequences of devolution for the House of Commons, would be chaired by former Clerk of the House of Commons, Sir William McKay, and would have one member from each of the devolved countries. The McKay Commission reported in March 2013.[34]

English votes for English laws

On 22 October 2015 The House of Commons voted in favour of implementing a system of "English votes for English laws" by 312 votes to 270 after four hours of intense debate. Amendments to the proposed standing orders put forward by both Labour and The Liberal Democrats were defeated. Scottish National Party MPs criticized the measures stating that the bill would render Scottish MPs as "second class citizens".[35] Under the new procedures, if the Speaker of The House determines if a proposed bill or statutory instrument exclusively affects England, England and Wales or England, Wales and Northern Ireland, then legislative consent should be obtained via a Legislative Grand Committee. This process will be performed at the second reading of a bill or instrument and is currently undergoing a trial period, as an attempt at answering the West Lothian question.[36] English votes for English laws was suspended in April 2020,[37] and in July 2021 the House of Commons abolished it, returning to the previous system with no special mechanism for English laws.[38]

Sub-national

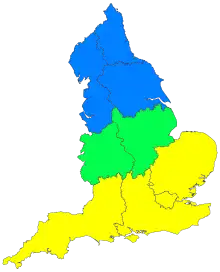

England has three distinct sub-national areas; the north, middle and south.

North

Northern England has a statutory transport body, Transport for the North. Multiple bodies are or have advocated for further devolution to Northern England. The all-party parliamentary group Northern Powerhouse Partnership is one of these, made up of businesses and civil leaders. The Northern Party was a potlitical party established to campaign for Devolution to the North of England through the creation of a Regional Government over covering the six historic counties of the region.[39][40] The Campaign aimed to create a Northern Government with tax-raising powers and responsibility for policy areas including economic development, education, health, policing and emergency services.[41][42]

The Northern Independence Party is a secessionist and democratic socialist party founded in 2020, in response to the perceived growth of the North–South divide in England,[43] aiming for the formation of an independent north of England under the name of Northumbria, after the early medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the same name. The party currently has no elected representatives in parliament.[44]

Regional

Devolution for England was proposed in 1912 by the Member of Parliament for Dundee, Winston Churchill, as part of the debate on Home Rule for Ireland. In a speech in Dundee on 12 September, Churchill proposed that the government of England should be divided up among regional parliaments, with power devolved to areas such as Lancashire, Yorkshire, the Midlands and London as part of a federal system of government.[45][46]

The division of England into provinces or regions was explored by several post-Second World War royal commissions. The Redcliffe-Maud Report of 1969 proposed devolving power from central government to eight provinces in England. In 1973 the Royal Commission on the Constitution (United Kingdom) proposed the creation of eight English appointed regional assemblies with an advisory role; although the report stopped short of recommending legislative devolution to England, a minority of signatories wrote a memorandum of dissent which put forward proposals for devolving power to elected assemblies for Scotland, Wales and five Regional Assemblies in England.[47]

The 1966-1969 Redcliffe-Maud Report recommended the abolition of all existing two-tier councils and council areas in England and replacing them with 58 new unitary authorities alongside three metropolitan areas (Merseyside, 'Selnec', and the West Midlands). These would have been grouped into eight provinces with a provincial council each. The report was initially accepted "in principle" by the government.

In April 1994, the Government of John Major created a set of ten Government Office Regions for England to coordinate central government departments at a provincial level.[48] Regional Development Agencies were set up in 1998 under the Government of Tony Blair to foster economic growth around England. These Agencies were supported by a set of eight newly created Regional Assemblies, or Chambers. These bodies were not directly elected but members were appointed by local government and local interest groups.

In a white paper published in 2002, the government proposed decentralisation of power across England similar to that done for Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland in 1998.[49] Regional Assemblies were abolished between 2008 and 2010, but the Regions of England continue to be used in certain governmental administrative functions.

Greater London

Following a referendum in 1998, a directly elected administrative body was created for Greater London, the Greater London Authority which has “accrued significantly more power than were originally envisaged.” [50]

Within the Greater London Authority (GLA) are the elected Mayor of London and London Assembly. The GLA is colloquially referred to as the City Hall and their powers include overseeing Transport for London, work of the Metropolitan Police, London Fire and Emergency Planning Authority, various redevelopment corporations, and the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park.[51] Part of the work of the GLA entails monitoring and furthering devolution in London: the Devolution Working Group[52] is a committee which is particularly aimed at this. In 2017 the work of these authorities along with Public Health England achieved a devolution agreement with the national government in regard to some healthcare services.[53][54]

North East England

A proposal to devolve political power to a fully elected Regional Assembly was put to public vote in the 2004 North East England devolution referendum. This, however, was defeated 78% to 22%, resulting in the cancellation of subsequent referendums planned in North West England and Yorkshire and the Humber, with the government abandoning its plans of regional devolution altogether.[55] As well as facilitating an elected assembly, the proposal would also have reorganised local government in the area.

Yorkshire

Arguments for devolution to Yorkshire, which has a population of 5.4 million – similar to Scotland – and whose economy is roughly twice as large as that of Wales, include focus on the area as a cultural region or even a nation separate from England,[56] whose inhabitants share common features.

This cause has also been supported by the cross-party One Yorkshire group of 18 local authorities (out of 20) in Yorkshire. One Yorkshire has sought the creation of a directly elected mayor of Yorkshire, devolution of decision-making to Yorkshire, and giving the county access to funding and benefits similar to combined authorities.[57] Various proposals differ between establishing this devolved unit in Yorkshire and the Humber (which excludes parts of Yorkshire and includes parts of Lincolnshire), in the county of Yorkshire as a whole, or in parts of Yorkshire, with Sheffield and Rotherham each opting for a South Yorkshire Deal.[58][59] This has been criticised by proponents of the One Yorkshire solution, who have described it as a Balkanisation of Yorkshire and a waste of resources.[58]

The Yorkshire Devolution Movement is an associate parliamentary group campaigning for a directly elected parliament for the whole of the traditional county of Yorkshire with powers second to no other devolved administration in the UK.[60]

The Yorkshire Party advocates for the establishment of a devolved Yorkshire Assembly within the UK, with powers over education, environment, transport and housing. In the 2019 European Parliament election, it received over 50,000 votes in the Yorkshire and the Humber constituency.[61] In the 2021 West Yorkshire mayoral election,[62] 2022 South Yorkshire mayoral Election,[63] and the 2022 Wakefield By-Election,[64] the Yorkshire Party beat major parties, being the third most voted for political party in each election.

Sub-regional

After the proposal of devolution to regions failed, the government pursued the concept of city regions. The 2009 Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act provided the means for the creation of combined authorities based upon city regions, a system of cooperation between authorities. Multiple combined authorities where created in the early-to-mid-2010s,[65] the oldest of these being the Greater Manchester Combined Authority established in 2011.[66] Over the latter part of the 2010s and into the 2020s, the national government has progressed with proposed deals for more groups of local authorities to devolve at a sub-regional level.[67] The Local Government Association keeps a register of up to date devolution proposals.[68]

As of the beginning of 2021, ten combined authorities exist, nine of which have a directly elected mayor. The powers given to the combined authorities are smaller compared to the powers of the devolved national governments; they are limited largely to the economy, transport, and planning.[69]

Cornwall

There is a movement that supports devolution in Cornwall. A law-making Cornish Assembly is party policy for the Liberal Democrats, Mebyon Kernow, Plaid Cymru and the Greens.[70][71] A Cornish Constitutional Convention was set up in 2001 with the goal of establishing a Cornish Assembly. Several Cornish Liberal Democrat MPs such as Andrew George, Dan Rogerson and former MP Matthew Taylor are strong supporters of Cornish devolution.[72]

On 12 December 2001, the Cornish Constitutional Convention and Mebyon Kernow submitted a 50,000-strong petition supporting devolution in Cornwall to 10 Downing Street.[73][74] This was over 10% of the Cornish electorate, the figure that the government had stated was the criteria for calling a referendum on the issue.[75] In December 2007 Cornwall Council leader David Whalley stated that "There is something inevitable about the journey to a Cornish Assembly".[76]

A poll carried out by Survation for the University of Exeter in November 2014 found that 60% were in favour of power being devolved from Westminster to Cornwall, with only 19% opposed and 49% were in favour of the creation of a Cornish Assembly, with 31% opposed.[77]

In January 2015 Labour's Shadow Chancellor promised the delivery of a Cornish assembly in the next parliament if Labour are elected. Ed Balls made the statement whilst on a visit to Cornwall College in Camborne and it signifies a turn around in policy for the Labour party who in government prior to 2010 voted against the Government of Cornwall Bill 2008–09.[78]

Cornwall has also been discussed as a potential area for further devolution and therefore a federal unit, particularly promoted by Mebyon Kernow. Cornwall has a distinct language and the Cornish have been recognised as a national minority within the United Kingdom, a status shared with the Scots, the Welsh, and the Irish.[79] The electoral reform society conducted a poll which showed a majority supported more local decision making: 68% of councillors supported increased powers for councils and 65% believed local people should be more involved in the decision making process.[80]

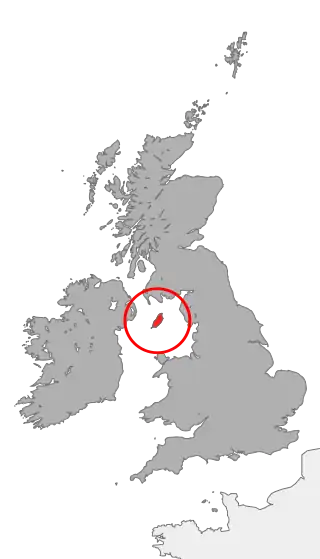

Crown dependencies

The legislatures of the Crown Dependencies are not devolved as their origins predate the establishment of the United Kingdom and their attachment to the British Crown, and the Crown Dependencies are not part of the United Kingdom. However, the United Kingdom has redefined its formal relationship with the Crown Dependencies since the late 20th century.

Crown dependencies are possessions of the British Crown, as opposed to overseas territories or colonies of the United Kingdom. They comprise the Channel Island bailiwicks of Jersey and Guernsey, and the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea.[81]

For several hundred years, each has had its own separate legislature, government and judicial system. However, as possessions of the Crown they are not sovereign nations in their own right and the British Government is responsible for the overall good governance of the islands and represents the islands in international law. Acts of the UK Parliament are normally only extended to the islands only with their specific consent.[82] Each of the islands is represented on the British-Irish Council.

The Lord Chancellor, a post in the UK Government, is responsible for relations between the government and the Channel Islands. All insular legislation must be approved by the King in Council and the Lord Chancellor is responsible for proposing the legislation on the Privy Council. He can refuse to propose insular legislation or can propose it for the King's approval.

In 2007–2008, each Crown Dependency and the UK signed agreements[83] that established frameworks for the development of the international identity of each Crown Dependency. Among the points clarified in the agreements were that:

- the UK has no democratic accountability in and for the Crown Dependencies which are governed by their own democratically elected assemblies;

- the UK will not act internationally on behalf of the Crown Dependencies without prior consultation;

- each Crown Dependency has an international identity that is different from that of the UK;

- the UK supports the principle of each Crown Dependency further developing its international identity;

- the UK recognises that the interests of each Crown Dependency may differ from those of the UK, and the UK will seek to represent any differing interests when acting in an international capacity; and

- the UK and each Crown Dependency will work together to resolve or clarify any differences that may arise between their respective interests.

Jersey has moved further than the other two Crown dependencies in asserting its autonomy from the United Kingdom. The preamble to the States of Jersey Law 2005 declares that 'it is recognized that Jersey has autonomous capacity in domestic affairs' and 'it is further recognized that there is an increasing need for Jersey to participate in matters of international affairs'.[84] In July 2005, the Policy and Resources Committee of the States of Jersey established the Constitutional Review Group, chaired by Sir Philip Bailhache, with terms of reference 'to conduct a review and evaluation of the potential advantages and disadvantages for Jersey in seeking independence from the United Kingdom or other incremental change in the constitutional relationship, while retaining the Queen as Head of State'. The Group's 'Second Interim Report' was presented to the States by the Council of Ministers in June 2008.[85] In January 2011, one of Jersey's Council of Ministers was for the first time designated as having responsibility for external relations and is often described as the island's 'foreign minister'.[86][87] Proposals for Jersey independence have not, however, gained significant political or popular support.[88][89] In October 2012 the Council of Ministers issued a "Common policy for external relations"[90] that set out a number of principles for the conduct of external relations in accordance with existing undertakings and agreements. This document noted that Jersey "is a self-governing, democratic country with the power of self-determination" and "that it is not Government policy to seek independence from the United Kingdom, but rather to ensure that Jersey is prepared if it were in the best interests of Islanders to do so". On the basis of the established principles the Council of Ministers decided to "ensure that Jersey is prepared for external change that may affect the Island’s formal relationship with the United Kingdom and/or European Union".

There is also public debate in Guernsey about the possibility of independence.[91][92] In 2009, however, an official group reached the provisional view that becoming a microstate would be undesirable[93] and it is not supported by Guernsey's Chief Minister.[94]

In 2010, the governments of Jersey and Guernsey jointly created the post of director of European affairs, based in Brussels, to represent the interests of the islands to European Union policy-makers.[95]

Since 2010 the Lieutenant Governors of each Crown dependency have been recommended to the Crown by a panel in each respective Crown dependency; this replaced the previous system of the appointments being made by the Crown on the recommendation of UK ministers.[96][97]

Competences of the devolved governments

Northern Ireland, Scotland & Wales enjoy different levels[98] of legislative, administrative and budgetary autonomy. The devolved administration has exclusive powers in certain policy areas, while in others, responsibility is shared and some areas of policy in the specific area are not under the control of the devolved administration. For example, while policing and criminal law may be a competence of the Scottish Government, the UK Government remains responsible for anti-terrorism and coordinates serious crime through the NCA.

Scotland

Under section 30 of the Scotland Act 1998, powers that are reserved to the UK Parliament can be temporarily devolved to the Scottish Parliament.[99]

A section 30 Order has been granted 16 times since the creation of the Scottish Parliament and covers a variety of areas including the power to hold a referendum on independence.[99]

See also

- List of current heads of government in the United Kingdom and dependencies

- British national identity – State or quality of embodying British characteristics

- Proposed United Kingdom Confederation – Proposed constitutional reform of a confederation of sovereign states

- Intergovernmental relations in the United Kingdom – Of central and devolved administrations

- Unionism in the United Kingdom – Support for continued unity of the UK

- Scottish devolution – Since 1707 Acts of Union to present day

- Welsh devolution – Transfer of legislative power to Welsh authorities from UK government

- Welsh independence – Welsh political philosophy

- Outsourcing – Contracting formerly internal tasks to an external organization

- Constitutional status of Cornwall – Overview of the constitutional status of Cornwall within the United Kingdom

- Constitutional status of Orkney, Shetland and the Western Isles – Status of the Scottish islands

- Barnett formula – Share due to devolved administrations

- Devolved, reserved and excepted matters – UK public policy areas

- Asymmetric federalism – Imbalance of powers as between members

Notes

- Following the Anglo-Irish Treaty that provided (among other matters) for the partition of Ireland, the Irish Free State left the UK at the same time, initially as a dominion of the British Empire (like Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa), subsequently to become an independent republic.

- This function of the bill is recognised by all the published scholarship on the legislation

References

- [18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25]

- "IRA Ceasefire". The Search for Peace. BBC. 2005. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- Jackson, Alvin (2003) Home Rule, an Irish History 1800–2000, ISBN 0-7538-1767-5.

- "March target date for devolution", BBC News Online, 13 October 2006.

- "NI deal struck in historic talks". BBC. 26 March 2007.

- "Historic return for NI Assembly". BBC. 8 May 2007.

- "Ian Paisley retires as NI Assembly completes historical first full term". BBC News. 25 March 2011.

- Report, NI Assembly, 12 May 2011, archived from the original on 6 August 2011

- "Stormont deal: Parties return to assembly after agreement". BBC News. 11 March 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- "Northern Ireland Assembly Election Results 2022". BBC. 6 May 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- Phillips, Alexa (13 May 2022). "Northern Ireland Assembly fails to elect Speaker after DUP blocks formation of government". Sky News.

- "Northern Ireland Protocol: Assembly Speaker blocked by DUP for second time". BBC News. 30 May 2022.

- Swinney, John (24 August 2022). "GERS figures: Why Scotland's deficit is falling faster than UK Government".

- McEwen, Nicola (8 March 2016). "Can Holyrood be one of the most powerful devolved parliaments in the world?".

- Leask, David (26 February 2016). "Is Scotland one of the most powerful devolved places in the world? Probably not..."

- Watson, Jeremy. "Independence vote will be key part of SNP manifesto". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- McCall, Chris (22 October 2020). "Scottish independence referendum 'could happen in 2021' says senior SNP MSP". Daily Record. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- Dougan, Michael; Hunt, Jo; McEwen, Nicola; McHarg, Aileen (2022). "Sleeping with an Elephant: Devolution and the United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020". Law Quarterly Review. London: Sweet & Maxwell. 138 (Oct): 650–676. ISSN 0023-933X. SSRN 4018581. Retrieved 4 March 2022 – via Durham Research Online.

The Act has restrictive – and potentially damaging – consequences for the regulatory capacity of the devolved legislatures...This was not the first time since the Brexit referendum that the Convention had been set aside, but it was especially notable given that the primary purpose of the legislation was to constrain the capacity of the devolved institutions to use their regulatory autonomy...in practice, it constrains the ability of the devolved institutions to make effective regulatory choices for their territories in ways that do not apply to the choices made by the UK government and parliament for the English market.

- Masterman, Roger; Murray, Colin (2022). "The United Kingdom's Devolution Arrangements". Constitutional and Administrative Law (Third ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 471–473. doi:10.1017/9781009158497. ISBN 9781009158503.

UK Internal Market Act 2020 imposed new restrictions on the ability of the devolved institutions to enact measures...mutual recognition and non-discrimination requirements mean that standards set by the legislatures in Wales and Scotland cannot restrict the sale of goods which are acceptable in other parts of the UK. In other words, imposing such measures would simply create competitive disadvantages for businesses in Wales and Scotland; they would not change the product standards or environmental protections applicable to all goods which can be purchased in Wales and Scotland.

- Keating, Michael (2 February 2021). "Taking back control? Brexit and the territorial constitution of the United Kingdom". Journal of European Public Policy. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis. 28 (4): 491–509. doi:10.1080/13501763.2021.1876156. hdl:1814/70296. S2CID 234066376.

The UK Internal Market Act gives ministers sweeping powers to enforce mutual recognition and non-discrimination across the four jurisdictions. Existing differences and some social and health matters are exempted but these are much less extensive than the exemptions permitted under the EU Internal Market provisions. Only after an amendment in the House of Lords, the Bill was amended to provide a weak and non-binding consent mechanism for amendments (equivalent to the Sewel Convention) to the list of exemptions. The result is that, while the devolved governments retain regulatory competences, these are undermined by the fact that goods and services originating in, or imported into, England can be marketed anywhere.

- Kenny, Michael; McEwen, Nicola (1 March 2021). "Intergovernmental Relations and the Crisis of the Union". Political Insight. London: SAGE Publishing; Political Studies Association. 12 (1): 12–15. doi:10.1177/20419058211000996.

That phase of joint working was significantly damaged by the UK Internal Market Act, pushed through by the Johnson government in December 2020...the Act diminishes the authority of the devolved institutions, and was vehemently opposed by them.

- Wolffe, W James (7 April 2021). "Devolution and the Statute Book". Statute Law Review. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 42 (2): 121–136. doi:10.1093/slr/hmab003. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

the Internal Market Bill—a Bill that contains provisions which, if enacted, would significantly constrain, both legally and as a matter of practicality, the exercise by the devolved legislatures of their legislative competence; provisions that would be significantly more restrictive of the powers of the Scottish Parliament than either EU law or Articles 4 and 6 of the Acts of the Union...The UK Parliament passed the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 and the Internal Market Act 2020 notwithstanding that, in each case, all three of the devolved legislatures had withheld consent.

- Wincott, Daniel; Murray, C. R. G.; Davies, Gregory (17 May 2021). "The Anglo-British imaginary and the rebuilding of the UK's territorial constitution after Brexit: unitary state or union state?". Territory, Politics, Governance. Abingdon/Brighton: Taylor & Francis; Regional Studies Association. 10 (5): 696–713. doi:10.1080/21622671.2021.1921613.

Taken as a whole, the Internal Market Act imposes greater restrictions upon the competences of the devolved institutions than the provisions of the EU Single Market which it replaced, in spite of pledges to use common frameworks to address these issues. Lord Hope, responsible for many of the leading judgments relating to the first two decades of devolution, regarded the legislation's terms as deliberately confrontational: 'this Parliament can do what it likes, but a different approach is essential if the union is to hold together'.

- Dougan, Michael; Hayward, Katy; Hunt, Jo; McEwen, Nicola; McHarg, Aileen; Wincott, Daniel (2020). UK and the Internal Market, Devolution and the Union. Centre on Constitutional Change (Report). University of Edinburgh; University of Aberdeen. pp. 2–3. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Dougan, Michael (2020). Briefing Paper. United Kingdom Internal Market Bill: Implications for Devolution (PDF) (Report). Liverpool: University of Liverpool. pp. 4–5. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Name Change Information". Welsh Parliament. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Williams, Shirley (16 September 2014). "How Scotland could lead the way towards a federal UK". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- Hazell, Robert (2006). "The English Question". Publius. 36 (1): 37–56. doi:10.1093/publius/pjj012.

- Carrell, Severin (16 January 2007). "Poll shows support for English parliament". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- Ormston, Rachel; Curtice, John (December 2010). "Resentment or contentment? Attitudes towards the Union ten years on" (PDF). National Centre for Social Research. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- Curtice, John (February 2010). "Is an English backlash emerging? Reactions to devolution ten years on" (PDF). Institute for Public Policy Research. p. 3. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- Kumar, Krishan (2010). "Negotiating English identity: Englishness, Britishness and the future of the United Kingdom". Nations and Nationalism. 16 (3): 469–487. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8129.2010.00442.x.

- "Answer sought to the West Lothian question". BBC News Scotland. 8 September 2011. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- BBC News, England-only laws 'need majority from English MPs' , 25 March 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013

- Sheehy, James (22 October 2015). "Scottish MPs denounce Bill regarding devolution powers". The Independent.

- James, Sheehy (22 October 2015). "English Votes For English Laws". The BBC.

- Maguire, Patrick; Wright, Oliver; Andrews, Kieran (16 June 2021). "Scottish MPs could vote down English laws in Michael Gove's attempt to save Union". The Times. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- "Commons scraps English votes for English laws". BBC News. 13 July 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- Rosthorn, Andrew (1 October 2014). "Campaign for the North wants the lost kingdom of Eric Bloodaxe". Tribune. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- White, Steve (1 October 2014). "Viking referendum demands a Northern state based on kingdom of Erik Bloodaxe". Daily Mirror. Trinity Mirror.

- Blackhurst, Chris (2 October 2014). "It's not because I'm sentimental about the North that I believe it needs devolved powers". The Independent. Independent Print Ltd.

- Staff writer (6 October 2014). "Ex-MP pushes for northern parliament". The Gazette. Johnston Press.

- "Northern Independence Party". Northern Independence Party.

- "Political parties in Parliament - UK Parliament".

- "Local Parliaments For England. Mr. Churchill's Outline of a Federal System, Ten Or Twelve Legislatures". The Times. 13 September 1912. p. 4.

- "Mr. Winston Churchill's speech at Dundee". The Spectator. 14 September 1912. p. 2. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- Smith, David M.; Wistrich, Enid (2014). Devolution and localism in England. p. 6. ISBN 9781472430793. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Audretsch, David B.; Bonser, Charles F., eds. (2002). Globalization and regionalization : challenges for public policy. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 25–28. ISBN 9780792375524. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- House of Commons Justice Committee (2009). Devolution : a decade on. London: TSO. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9780215530387. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Brown, Richard (September 2015). "More radical thinking than we are currently seeing will be needed to secure the devolved powers that London needs". Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "The Greater London Authority (GLA) – Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship And Smes – European Commission". Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "Committee details – Devolution Working Group – London City Hall". Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "What health and care devolution means for London – London City Hall". 17 May 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "London health devolution agreement – GOV.UK". Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Jones, Bill; Norton, Philip, eds. (2004). Politics UK. Routledge. p. 238. ISBN 9781317581031. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- "Yorkshire could be ‘God’s Own Country’, says Leeds professor", Yorkshire Evening Post, 12 September 2014.

- Services, Web. "One Yorkshire devolution". City of York Council. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- "Government rejects Yorkshire devolution". BBC News. 12 February 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- "West Yorkshire devolution deal could be signed by March as Ministers start formal talks with local leaders". www.yorkshirepost.co.uk. 29 January 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- Kirby, Dean (26 August 2015). "Campaigners want to ditch George Osborne's Yorkshire devolution plans and create Northern Powerhouse". independent.

- "Brexit Party take three of Yorkshire & Humber region's six seats while Tories and Ukip lose out". ITV News. 27 May 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- "Election results 2021: Tracy Brabin elected West Yorkshire mayor". BBC News. 9 May 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- "South Yorkshire Mayor Election 2022 Candidates and Results". BBC News. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- "Wakefield by-election: Full results as Labour regains city seat from Tories". www.yorkshirepost.co.uk. 24 June 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- "Devolution deals". Local Government Association. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- Lupton, Ruth; Hughes, Ceri; Peake-Jones, Sian; Cooper, Kerris (2018). "City-region devolution in England". Social Policies and Distributional Outcomes in a Changing Britain. SPDO research paper 2.

- "Devolution Register". Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- "Devolution deals". Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- Lupton, Ruth; Hughes, Ceri; Peake-Jones, Sian; Cooper, Kerris (2018). "City-region devolution in England". Social Policies and Distributional Outcomes in a Changing Britain. SPDO research paper 2.

- Demianyk, Graham (10 March 2014), "Liberal Democrats vote for Cornish Assembly", Western Morning News, archived from the original on 7 April 2014, retrieved 20 September 2014

- Green Party of England and Wales (2 May 2014), Green Party leader reaffirms support for Cornish Assembly, retrieved 20 September 2014

- "Andrew George MP, Press release regarding Cornish devolution October 2007". Archived from the original on 25 December 2007.

- Cornish Constitutional Convention. "The Cornish Constitutional Convention". Cornishassembly.org. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- "11th December 2001– Government gets Cornish assembly call". BBC News. 11 December 2001. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- Great Britain: Parliament: House of Commons: ODPM: Housing, Planning, Local Government and the Regions Committee, Draft Regional Assemblies Bill, The Stationery Office, 2004.

- Cornish Constitutional Convention. "Cornwall Council leader supports Cornish devolution". Cornishassembly.org. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- Demianyk, G (27 November 2014). "South West councils make devolution pitch as Scotland gets income tax powers". Western Morning News. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- "Labour's Devolution Pledge For Cornwall". Pirate FM. UKRD. 23 January 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- "Cornish people are formally declared a national minority". The Independent. 23 April 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- "Democracy Made in England: Where Next for English Local Government?". www.electoral-reform.org.uk. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- "Crown Dependencies, 8th Report of 2009–10, HC 56-1". House of Commons Justice Select Committee. 23 March 2010.

- In relation to Jersey, see "Jersey law course". Institute of Law Jersey. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013.

- States of Jersey Law 2005 (PDF). States of Jersey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 May 2012.

- Second Interim Report of the Constitution Review Group (PDF). States of Jersey. 27 June 2008.

- "Meet our new foreign minister". Jersey Evening Post. 14 January 2011. Archived from the original on 17 January 2011.

- "Editorial: A new role of great importance". Jersey Evening Post. 17 January 2011. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011.

- "Editorial: Legal ideas of political importance". Jersey Evening Post. 21 September 2010. Archived from the original on 2 July 2011.

- Sibcy, Andy (17 September 2010). "Sovereignty or dependency on agenda at conference". Jersey Evening Post. Archived from the original on 2 July 2011.

- "Common policy for external relations" (PDF). States of Jersey. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- Ogier, Thom (27 October 2009). "Independence—UK always willing to talk". Guernsey Evening Press. Archived from the original on 18 March 2012.

- Prouteaux, Juliet (23 October 2009). "It IS time to loosen our ties with the UK". Guernsey Evening Press. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009.

- Ogier, Thom (13 October 2009). "Full independence would frighten away investors and firms". Guernsey Evening Press. Archived from the original on 20 October 2009.

- Tostevin, Simon (9 July 2008). "Independence? Islanders don't want it, says Trott". Guernsey Evening Press. Archived from the original on 22 November 2008.

- Staff writer (27 January 2011). "Channel Islands' "man in Europe" appointed". Jersey Evening Post. Archived from the original on 2 February 2011.

- Staff writer (6 July 2010). "£105,000 – the tax-free reward for being a royal rep". Jersey Evening Post. Archived from the original on 16 August 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- Ogier, Thom (3 July 2010). "Guernsey will choose its next Lt-Governor". Guernsey Evening Press. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- "The current Welsh devolution settlement" (PDF). commissionondevolutioninwales. Commission on Devolution in Wales. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2014.

- Sim, Philip (19 December 2019). "Scottish independence: What is a section 30 order?". BBC News.

Further reading

- Bogdanor, Vernon (2001). Devolution in the United Kingdom. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19280128-9.

- Swenden, Wilfried; McEwen, Nicola (July–September 2014). "UK devolution in the shadow of hierarchy? Intergovernmental relations and party politics" (PDF). Comparative European Politics. 12 (4–5): 488–509. doi:10.1057/cep.2014.14. hdl:20.500.11820/61b8bf3f-2261-4e4f-8467-a68131cc5dcc. S2CID 144005452.

- Blick, Andrew (2015), "Magna Carta and contemporary constitutional change", History & Policy.