Dhamar Governorate

Dhamar[1] (Arabic: ذَمَار, romanized: Ḏamār), also spelt Thamar, is a governorate of Yemen located in the central highlands.

Dhamar

Arabic: محافظة ذَمَار | |

|---|---|

Governorate | |

Baynun in Al-Hada' District of Dhamar Governorate | |

| |

| Coordinates: 15°40′N 43°56′E | |

| Country | Yemen |

| Region | Azal Region |

| Seat | Dhamar, Yemen |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9,495 km2 (3,666 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Total | 1,603,000 |

| • Density | 170/km2 (440/sq mi) |

Etymology

Dhamar is named after Dhamar Ali Yahbur II, who ruled the area that now comprises Dhamar Governorate as King of Saba', Dhu Raydan, Hadhramaut and Yamnit. His name means "Owner of the order".

Geography

Dhamar Governorate has a total area of 7,586–7,935 km2 (2,929–3,064 sq mi), and is divided among 12 administrative districts (Arabic: مُدِيْرِيَّأت, romanized: Mudīriyyāt) and further divided into 314 'Uzlat (sub-districts). According to the 2004 census, the population was 1,329,229 people, most of whom live in the governorate's 3,262 villages. A visitor may enter the governorate about 70 km (43 mi) south of the Sana'a Airport. The center of the governorate is about 100 km (62 mi) from Sana'a, the capital of Yemen. It is located to the south and southeast of Sana'a Governorate, to the north of Ibb Governorate, to the east of Al Hudaydah Governorate and to the northwest of Al Bayda' Governorate in the central highlands of Yemen.

Much of the governorate lies between 1,600–3,200 m (5,200–10,500 ft) above sea level, with topography that varies from high mountains to deep valleys, upland plains and plateaus. Major mountains include Isbil, Al-Lisi, Duran, the two Wusab mountain ranges, and the 'Utamah mountains. Jahran, in the north-central part of the governorate, is its most extensive plain. A volcanic field, Harras of Dhamar, extends 80 km (50 mi) to the east of Dhamar town.[2]

The governorate's climate is temperate, although the central and eastern sections of the governorate tend to be cold during the winter, while the valleys and western slopes are warmer. The average temperatures range from 10 to 19 °C (50 to 66 °F) in summer, and from 8 to −1 °C (46 to 30 °F) in winter. Dhamar is the most consistently elevated governorate in Yemen, with most of the land lying at over 2,500 metres (8,200 ft). The climate, though, remains hot during the day, with typical maxima of between 25 and 30 °C (77 and 86 °F), but frosts are very common at night during the winter months. During January 1986, temperatures are believed to have fallen as low as −12 °C (10 °F). Although no reliable rain gauge exists within the governorate, it is estimated that annual rainfall would range between 400 and 500 millimetres (16 and 20 in) concentrated exclusively in the summer months, especially in July and August but also in March and April. Occasionally, floods can prove disastrous though causing extensive erosion, notably in early April 2006.

Adjacent governorates

- Sanaa Governorate (north)

- Al Bayda Governorate (east)

- Ibb Governorate (south)

- Al Hudaydah Governorate (west)

- Raymah Governorate (west)

Districts

Dhamar Governorate is divided into the following 12 districts. These districts are further divided into sub-districts, and then further subdivided into villages:

History

Modern scientific studies have confirmed human activity at Dhamar since the Neolithic period, starting around 6000 BC and continuing through the Bronze Age. The site of the Hammat al-Qa' – 10 km (6.2 mi) to the east of Ma’bar city – is one of the most prominent and significant Bronze Age locations in the Arabian Peninsula. The historic period of the South Arabian civilization in Yemen began between the 12th and 10th century BC. Dhamar contributed actively in the march of civilisation in Yemen, with ancient monuments dating back to 1000 B.C. at places such as al-Sha'b al-Aswad and Masna'at Marya.

During the 2nd century BC, Raydanites established themselves at Zafar, about 50 km (31 mi) south of Dhamar, and they rallied the Himyarite tribes in their fight with Sabaean forces. Dhamar became the strategic place for the Raydanites. By the 2nd century AD, Naqil Yislah – 50 km (31 mi) to the north of Dhamar city – was the dividing line between the Sabaeans and the Raydanites under the leadership of the king Yasir Yahsadaq. The Raydanites succeeded, under the leadership of the king Yasir Yahnam and his son Shamar Yahrash, in ending the struggle for their favour, besting their adversaries, and extending their influence and power to the Sabaean capital Ma'rib and the districts attached to it. This victory in 270 AD led to stability in Yemen in general, and in Dhamar in particular. Soon afterward, in about 293 AD, military forces sent by the Raydanite king Shamar Yahrash conquered Hadramaut. Yemen was now united, and in this new era, Dhamar witnessed prosperity, manifested in the reconstruction of cities and cultic centers, in the construction of palaces, temples and fortification walls, and in the creation of water facilities such as dams, tunnels, and diversion barriers. The bronze statues of Dhamar Ali Yahbar and his son Tha'ran Yahna'am discovered at Nakhlat Al-Hamra' are physical illustrations of the high cultural attainments of Yemen under these Himyarite kings. This cultural florescence came to an end when invading Abyssinians conquered Yemen and destroyed Himyarite cities, particularly in the governorate.

With the advent of Islam in the 7th century CE, tribes of Dhamar were the first in Yemen to embrace the faith at that time, and groups of its people traveled north to assure the survival of its new community, and to carry it to new lands. During the period of local states independent of the Abbasid caliphs, the Dhamar region was a center of interest to the competing powers. The governorate and city of Dhamar saw a period of florescence, especially during the time of Imam Sharaf Al-Din, who erected, between 1541 and 1543, Al-Madrasah al-Shamsiyyah (Arabic: ٱلْمَدْرَسَة ٱلشَّمْسِيَّة, "The Sun School") in Dhamar city; this school was for many centuries a center for diffusion of knowledge and culture.

During the 16th century, the Ottomans occupied Yemen, and Dhamar became one of the centers of Yemeni opposition to them. This resistance was eventually crowned by expulsion of the Ottomans from Yemen, at the hands of the Qasimi family, who took as their capital the town of Duran, northwest of Dhamar city. Dhamar endured, as did the other Yemeni governorates, severe hardships during the second Ottoman occupation in the 19th century, and under the Hamid al-Din imams during the 20th century. The latter government was forcefully overthrown by the Yemeni revolution, which broke out on 26 September 1962.

Archaeological and touristic sites

- Adrah Dam: Adrah village is famous for its large number of dams. Adrah Dam is 10 km (6.2 mi) to the east of Dhamar city. This dam dates back to the Himyarate civilization but its ancient monuments are still there. The Dam is a water barrier built between two mountains. It is 67 m (220 ft) long, 47 m (154 ft) high, and approximately 20 m (66 ft) wide.

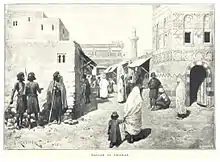

- Baynun: A vestigial city situated to the east of Dhamar city at Al-Hada'a province, Thouban zone. It is one of the archaeological sites whose history goes back to the Himyarate state. The most important sight there is Baynun Palace and some ruins of an ancient temple, as well as the two tunnels that are engraved into two mountains for transferring torrents' water from valley to valley. The first tunnel goes through Baynun Mountain, but it is plugged up because of the collapse of their entrance. However, the second, named Al-Nakoob Tunnel, is still in proper condition. Al-Nakoob tunnel is 150 m (490 ft) long, around 3 m (9.8 ft) wide, and 4.5 m (15 ft) high; there are some engravings in the wall of the tunnel that explain the aim of engraving and its age, which is about 1,800 years.

- Ani's Ali Bath: This is a natural mineral steam bath, lying northwest of Dhamar City, surrounded by green belt of various fruit farms. This bath is considered one of the known mineral steam bath in Yemen, and the visitors head for some special seasons in order to treat many kinds of diseases.

- Al-Lassi Bath: This is another steam-vapour bath, lying to the east of Dhamar City, on Al-Lassi citadel at 2,800 metres (9,200 feet) above the sea level. The citadel dates back to the 11th century A.H. Nearby, there are some remains of ancient sulfur mines.

- Doran Anss: It is about 15 km (9.3 mi) at the west of Mabear area; located on the north level of the mountain Al-Dameagh. It is the center of Anss zone and was the capital of Yemen during the Imam Al-Mutawakkil Ala-Allah Ismail ibn Al-Qasim in the 17th century A.D. The mountain, full of the green farms, was enclosed by a wall until its summit and surrounded by towers and castles that are built with huge stones. All of these ancient ruins are remaining until this day. There is a large historical mosque built by Al-Mutawakkil on the mount. In the middle of this mountain, there is a cave overlooking Doran City from the southwest side. Some of the old Himyarite engravings were found at the entrance and at the east side of that cave, but it is hard to get there.

- Automah: This province is located 16 km (9.9 mi) to southwest of Dhamar city, and about 155 km (96 mi) to the southwest of Sana'a. Automah is rich in the tourist components, something infrequently found in this area. Eventually, it was declared as a protected natural area.

Economy

Agriculture

Dhamar is a major agricultural region located midway between two of Yemen's three largest cities (Sana'a and Ta'izz). It produces, to some degree, almost all the crops grown in the Yemeni highlands. Dhamar town itself is notable as the only town in the former Yemen Arab Republic not to be walled: rather it is merely a town on open plains. The governorate is an important seat for the Zaydi branch of Shia Islam, which has long had a major influence in Yemen. The ancient kingdoms of Saba', Qataban and Himyar had their capitals within the present area of Dhamar, and the Himyarite kingdom with its capital at Yarim set up numerous terraces that allow for highly intensive agriculture throughout the region. Archeological studies attest to agricultural activity in Dhamar governorate starting some 7,000 years ago, through analysis of soil deposits at the Adra'ah dam east of Dhamar city. Dhamar's inhabitants have farmed and herded animals since that time. Taking advantage of the governorate's topographic diversity – plains, high plateaus, mountain slope valleys – farmers have introduced a diversity of crops, and agriculture became the governorate's principal economic activity. The governorate contains about 28,000 km2 (11,000 sq mi) of arable land, of which 12,000 km2 (4,600 sq mi) is currently devoted to cash crops such as corn, wheat and horticultural crops. The governorate also holds about 3,000 km2 (1,200 sq mi) devoted to growing vegetables and fruits that are marketed to other governorates of Yemen and to neighboring countries. The governorate is also well known for its coffee; its western districts such as Anis, Maghrab 'Ans and 'Utamah have a suitable climate for commercial coffee production. The coffee of Dhamar is distinguished by its high quality, and the variety known as Al-Faḍlī (الفضلي) is considered one of the best Yemeni coffees. Sheep herding, goat herding, and Arabian horse breeding are also important economic activities.

Traditional handicrafts

In addition to farming, the people practice traditional handicrafts such as weaving, embroidery, and making copper and pottery utensils in sizes suitable to different purposes such as cooking and water storage; jewellery in gold and silver is being made in a number of districts, as are making jambiyyahs. Extraction of building stone is also among the important crafts of the governorate. Stone quarries are scattered throughout all regions of the governorate, and the stone is marketed in the capital Sana'a and in other governorates of Yemen.

Extraction industries

The craft of extracting and shaping onyx as gemstones is a skill thousands of years old that continues today. The residents of the Anis and Ya’ar districts, in the west of Dhamar, are particularly active in this craft. These two areas are famous for providing the best kinds of onyx, which is highly prized and achieves wide circulation in local markets and also in those of neighboring countries. The governorate also contains other stones and minerals with industrial uses, such as limestone, gypsum, zeolite, biomese, saltpeter, feldspar, quartz, askuria and silicate sands. These raw materials occur in commercial quantities and qualities.

Public markets

Weekly public markets are widespread in the governorate. These markets usually are situated in crowded centers, to give the largest number of people the opportunity to benefit from them. The markets move from place to place during the week on a fixed round. Each market takes its name from the day of week on which it is held, such as Sūq al-Sabt (Arabic: سُوْق ٱلسَّبْت, "The Saturday Market") and Sūq al-Aḥad (Arabic: سُوْق ٱلْأَحَد, "The Sunday Market"). These markets sell agricultural and livestock products, and also the diverse craft products of the inhabitants of villages near the markets. Dhamar City hosts a weekly market called Sūq ar-Rabūʿ (Arabic: سُوْق ٱلرَّبُوْع, "The Wednesday Market"), but it also contains a permanent market. The latter market, distinguished by the diversity of products for sale, is divided into numerous sub-markets for products like grain, jambiyyah, coffee, fodder, and bread.

Traditions and customs

The governorate's people still maintain their noble traditions and customs for occasions such as weddings and religious festivals. On these occasions, people eager to perform traditional actions such as public dances, while garbed in traditionally appropriate clothing according customs inherited through generations. The dances, dress and verbal expressions at weddings differ in detail from district to district. Neighboring districts have the same names for the dances and a similar way of performing them, but these change toward the west so that in lower Wusab near the plain of Tihamah, the dances are completely different from those in eastern Dhamar.

References

- "Statistical Yearbook 2011". Central Statistical Organisation. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- Neumann van Padang, Maur (1963), Catalogue of the active volcanoes and solfatara fields of Arabia and the Indian Ocean, vol. 16, Rome: IAVCEI, pp. 1–64, OCLC 886615186