Ding Dong, Ding Dong

"Ding Dong, Ding Dong" is a song by English rock musician George Harrison, written as a New Year's Eve singalong and released in December 1974 on his album Dark Horse. It was the album's lead single in Britain and some other European countries, and the second single, after "Dark Horse", in North America. A large-scale production, the song incorporates aspects of Phil Spector's Wall of Sound technique, particularly his Christmas recordings from 1963. In addition, some Harrison biographers view "Ding Dong" as an attempt to emulate the success of two glam rock anthems from the 1973–74 holiday season: "Merry Xmas Everybody" by Slade, and Wizzard's "I Wish It Could Be Christmas Everyday". The song became only a minor hit in Britain and the United States, although it was a top-twenty hit elsewhere in the world.

| "Ding Dong, Ding Dong" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

US picture sleeve | ||||

| Single by George Harrison | ||||

| from the album Dark Horse | ||||

| B-side |

| |||

| Released | 6 December 1974 (UK) 23 December 1974 (US) | |||

| Genre | Rock | |||

| Length | 3:41 | |||

| Label | Apple | |||

| Songwriter(s) | George Harrison | |||

| Producer(s) | George Harrison | |||

| George Harrison singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

Harrison took the lyrics to "Ding Dong" from engravings he found at his nineteenth-century home, Friar Park, in Oxfordshire – a legacy of its eccentric founder, Frank Crisp. The song's "Ring out the old, ring in the new" refrain has invited interpretation as Harrison distancing himself from his past as a member of the Beatles, and as the singer farewelling his first marriage, to Pattie Boyd. As on much of the Dark Horse album, Harrison's vocals on the recording were hampered by a throat condition, due partly to his having overextended himself on business projects such as his recently launched record label, Dark Horse Records. Recorded at his Friar Park studio, the track includes musical contributions from Tom Scott, Ringo Starr, Alvin Lee, Ron Wood and Jim Keltner.

On release, the song met with an unfavourable response from many music critics, while others considered its musical and lyrical simplicity to be a positive factor for a contemporary pop hit. For the first time with one of his singles, Harrison made a promotional video for "Ding Dong", which features scenes of him miming to the track at Friar Park while dressed in a variety of Beatle-themed costumes. The song still receives occasional airplay over the holiday season. The video appears on the DVD in Harrison's eight-disc Apple Years 1968–75 box set, released in September 2014.

Background and composition

I was just sitting by the fire, playing the guitar, and I looked up on the wall, and there it was, carved into the wall in oak ... I thought, "God, it took me [four] years of looking at that before I realised it was a song" … [Friar Park] has got all these great things written all over the place.[1]

– George Harrison, on the inspiration behind "Ding Dong, Ding Dong", 1974

George Harrison purchased the 33-acre[2] Friar Park estate, in Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, in January 1970,[3] and soon afterwards composed "Ballad of Sir Frankie Crisp (Let It Roll)" as a tribute to the property's original owner,[4] an eccentric Victorian lawyer and horticulturalist named Frank Crisp.[5][6] Harrison included the song on his All Things Must Pass triple album, released in November 1970,[7] by which time he had begun incorporating into his new compositions some of the homilies and aphorisms that Crisp had inscribed around the property, 70 or more years before.[8] A four-line verse beginning "Scan not a friend with a microscopic glass" particularly resonated with Harrison,[9] who eventually used it in his 1975 song "The Answer's at the End".[10] It similarly took Harrison several years to turn two inspirational lines of verse from carvings in the house's drawing room into song lyrics.[11] These lines provided the repeated verse in "Ding Dong, Ding Dong": "Ring out the old, ring in the new" – which he took from the carving to the left of the fireplace – and "Ring out the false, ring in the true" – from the one to the right.[1] In his 1980 autobiography, I, Me, Mine, Harrison credits English poet Lord Tennyson as the original source for these lines.[12]

Authors Chip Madinger and Mark Easter describe "Ding Dong" as the "quickest song" that Harrison ever wrote, in terms of time spent on the composition.[11] The words for the song's middle eight – "Yesterday, today was tomorrow / And tomorrow, today will be yesterday" – came from another pair of inscriptions from Crisp's time at Friar Park.[1] Harrison found these lines in what he called "the garden building",[12] carved in stone around two matching windows.[1] The only other lyrics in "Ding Dong, Ding Dong" are the song title, repeated four times to serve as its chorus.[13][14] Sung in imitation of a clock chiming,[15][16] the chorus lyrics, combined with the message of those of the verse, lend the composition an obvious New Year's theme.[13] Harrison later described the song as "very optimistic", and suggested: "Instead of getting stuck in a rut, everybody should try ringing out the old and ringing in the new … [People] sing about it, but they never apply it to their lives."[1]

Harrison's other singles from the early 1970s – "My Sweet Lord", "What Is Life", "Bangla Desh" and "Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth)" – were similarly written very quickly.[17][18][19] In the case of "Ding Dong" and other tracks from the Dark Horse album, however, author Simon Leng recognises this haste as an example of Harrison abandoning his careful approach to his own music over the 1973–74 period, while remaining a "painstaking craftsman" on his concurrent projects with Ravi Shankar and the vocal duo Splinter.[20] Preceding this change, elements of the British media had ridiculed Harrison's continued association with the Hare Krishna movement,[21] and some music critics had objected to the overtly spiritual content of his 1973 album Living in the Material World.[22][23] With his marriage to Pattie Boyd all but over by the summer of 1973,[24] Harrison now wanted to be "one of the boys, not a spotlight-grabbing philosopher", according to Leng.[25]

Production

Initial recording

Harrison recorded the rhythm track for "Ding Dong, Ding Dong" at his home studio, FPSHOT, in late November 1973,[26] during the first sessions for Dark Horse.[27][28] Aside from himself, on acoustic guitar, the other musicians on the track were Gary Wright (piano), Klaus Voormann (bass), Ringo Starr and Jim Keltner (both on drums)[29] – all of whom had appeared on Living in the Material World earlier in the year.[30] The recording engineer was Phil McDonald.[31]

The sessions coincided with a period of domestic turbulence at Friar Park, with Harrison and Boyd both involved in extramarital affairs.[32] They saw in the 1973–74 New Year with a party at Starr's Tittenhurst Park mansion – which was an "absolute dud" of a night, according to their friend Chris O'Dell, due to Harrison having openly declared his love for Starr's wife, Maureen Starkey, a few days before.[33] Boyd recalls that Harrison told her at the party: "Let's have a divorce this year."[34][nb 1]

Overdubbing

Harrison included a rough mix of "Ding Dong" on a tape he sent to Asylum Records boss David Geffen in January 1974,[11] shortly before travelling to India to visit Shankar and escape his unhappy domestic situation with Boyd.[36][37] The purpose of the tape was to find a distributor for albums by Harrison's future Dark Horse Records acts – Shankar Family & Friends by Shankar, and Splinter's The Place I Love[38] – both of which had started off as Harrison productions for the Beatles' Apple record label.[39][nb 2] He added two songs of his own on the tape, with introductory comments about "Ding Dong".[42]

It's one of them repetitious numbers which is gonna have 20 million people, with the Phil Spector nymphomaniacs, all doing backing vocals by the end of the day, and it's gonna be wonderful.[42]

– Harrison discussing the song on a taped message to a music industry executive, January 1974

As outlined to Geffen, Harrison went on to adopt the Wall of Sound production technique of his former collaborator, American producer Phil Spector, in his subsequent work on the track.[43][44] Harrison's musical arrangement reflects the influence of the 1963 album A Christmas Gift for You,[15] which contained Spector-produced songs by the Ronettes, the Crystals and Darlene Love,[45] while more recently Spector had co-produced the Apple Records single "Happy Xmas (War Is Over)" single, by John Lennon and Yoko Ono.[15] Some authors claim that with "Ding Dong", Harrison set out to create a seasonal "classic",[13] in an attempt to match the British chart success of "Happy Xmas" and particularly of Slade's "Merry Xmas Everybody"[46] and Wizzard's "I Wish It Could Be Christmas Everyday" – two glam rock singles that were major UK hits over the winter of 1973–74.[29] Leng cites the inclusion on the finished version of "Ding Dong" of harmonium and distorted electric guitars, similar to the Slade hit, while Harrison's use of baritone saxophones, two drummers and tubular bells, together with a female choir,[15] matched the arrangement on "I Wish It Could Be Christmas Everyday",[43] which was heavily influenced by Spector's sound.[47][nb 3] Having incorporated aspects of Spector's technique on Material World,[50][51] Harrison's aim with "Ding Dong, Ding Dong", according to Leng, was an update of the Wall of Sound that reflected "the glam rock mood of the day".[29]

Harrison overdubbed call-and-response guitar riffs by Alvin Lee and Ron Wood onto the 1973 rhythm track,[42] as well as his own slide guitars.[30] Further overdubs included baritone and tenor saxophone parts by Tom Scott,[52] and a second acoustic guitar, played by Mick Jones.[53] Harrison also contributed on organ, clavinet and percussion,[53] the last of which included tubular bells (or chimes), sleigh bells and zither.[42][nb 4]

Harrison's workload ensured that he was rushing to finish Dark Horse in October 1974 before beginning his North American tour with Shankar on 2 November.[55][56][nb 5] Described by Leng as "growled", Harrison's rough-sounding singing on "Ding Dong" shows the effects of a long-standing throat problem.[30] Due to a combination of overexertion and abuse, this condition worsened,[59][60] leading to him contracting laryngitis as he simultaneously completed his vocals for the album in Los Angeles and rehearsed for the tour.[61][62][nb 6] The female backing singers on the track remain uncredited.[13][65]

Release

In the United Kingdom, "Ding Dong, Ding Dong" was released as the lead single from Dark Horse on 6 December 1974 (as Apple R 6002).[66][67] The B-side was "I Don't Care Anymore", a non-album track[68] that Harrison recorded in a single take, specifically for the single.[69]

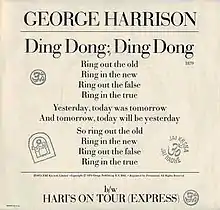

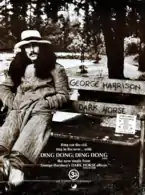

In the United States, where "Dark Horse" had already been issued in advance of the album, "Ding Dong" was coupled with the instrumental "Hari's on Tour (Express)" and released two days before Christmas (as Apple 1879).[67][70] Apple issued white label promotional discs to US radio stations, containing a 3:12 edit of the song.[11][66] The single was available in a picture sleeve consisting of the song lyrics printed on an off-white background, with stamped Om symbols and the FPSHOT logo.[71] The record's A-side face label included a photo of Harrison's new girlfriend, Olivia Arias, above the song information, whereas the UK single had Harrison's face on both sides.[72]

On the Dark Horse LP, the two face labels similarly alternated between a picture of Harrison and one of Arias.[73][74] Combined with the positioning of "Ding Dong" as the opening track on side two, this detail gave the impression that the song represented Harrison's ushering-in of his future wife and a farewell to Boyd.[75] In the album's inner-sleeve credits, Harrison listed one of the guitarists on the track as "Ron Would if you let him", a reference to Wood's brief affair with Boyd before she took up with Eric Clapton.[24] He also acknowledged Frank Crisp for having provided "spirit" on the recording.[76] In another farewell to the past,[77] Harrison signed the so-called "Beatles Agreement" papers in New York on 19 December, further severing the four former bandmates from the group's legal identity.[78][nb 7]

Rather than the smash hit that Harrison had hoped for,[16][42] "Ding Dong" was only moderately successful.[82] The single peaked at number 38 in Britain[83] and number 36 on America's Billboard Hot 100.[84][85] Madinger and Easter write that the single did "remarkably well", however, given that it was issued too late to take advantage of holiday-season programming.[11][nb 8] Harrison's single enjoyed more success internationally, climbing to number 10 in the Netherlands[88] and number 12 in Belgium.[89]

Despite "Ding Dong" having had what author Bruce Spizer terms a "respectable" chart run in America,[66] Apple distributor Capitol Records omitted the song from its 1976 compilation The Best of George Harrison,[90] which the company issued after Harrison had moved on to Dark Horse Records.[91] Following Dark Horse's CD release in 1992,[92] the song was unavailable in newly remastered form until the Apple Years Harrison reissues, released in September 2014.[93]

Critical reception

Contemporary reviews

Harrison created a massive arrangement for "Ding Dong, Ding Dong" that included a revived "Awaiting on You All" guitar orchestra … chiming bells, and an unnamed army of backup singers intoning the cheerleader chorus … The bad news was that Harrison's voice was on the road to oblivion, and the critics didn't get the joke at all.[42]

– Author Simon Leng

The majority of music critics were unimpressed with "Ding Dong, Ding Dong",[94] and its release came in the wake of unfavourable reviews for the North American tour.[95][96] In keeping with the song's message, Harrison refused to celebrate the past in his concerts by pandering to nostalgia for the Beatles,[59][97] and many in the mainstream music press criticised the poor state of his voice and his decision to feature Ravi Shankar so heavily in the program.[98][99]

In the UK, BBC DJ John Peel called "Ding Dong" "repetitive and dull" and accused Harrison of complacency,[100] while the NME's Bob Woffinden derided Dark Horse as "Just stuff and nonsense", adding: "You keep looking for saving graces, for words of enthusiasm to pass on – 'Ding Dong', you begin to think, for all its inane lyrics, has some spirit, but it really is very slight."[101] Harrison's standing there was not helped by the presence of "I Don't Care Anymore" on the B-side,[94] due to its casual delivery and the literal message in the song title.[102][103] In a more favourable review, for Melody Maker, Chris Irwin wrote of the single:

We've come to expect something with more substance than this glorified nursery rhyme from one of the most important musicians of the decade. True, it's catchy with a full chunky sound to bounce it along, but with an undeniable infectiousness of the sort normally associated with chicken pox or measles ... Curiously, records of such banality have a habit of selling in their zillions and this is bound to be a biggie. Hit.[104]

Jim Miller of Rolling Stone condemned Harrison for releasing an album with his voice blown and for his apparent disdain towards the Beatles' legacy. He dismissed the song as "a raspy stab at 'Auld Lang Syne'".[105] In High Fidelity, Mike Jahn wrote that of all the songs on Dark Horse, only "Ding Dong, Ding Dong" registered with him after three listens, but only due to his incredulity at the lyrics.[106]

By contrast, Michael Gross, writing in Circus Raves, defended Harrison's move away from the past, saying that Dark Horse matched the critically acclaimed All Things Must Pass, "surpassing it, at times, with its clarity of production and lovely songs", and he praised "Ding Dong", the title track and the Harrison–Ron Wood collaboration "Far East Man" as "all, simply, good songs".[52] While remarking on the surprisingly late release for a holiday-season single, Billboard's reviewer deemed the track an "Extremely listenable performance" and added: "George has a genuine hit sound to offer here that's just right for those early January time-to-change resolutions. Catchy, heavily percussive production in Harrison's uptempo guru vein … Get on it, jocks."[107] Cash Box described the single as a "rocking replacement for 'Auld Lang Syne,' featuring some of George's most inspiring production". The reviewer said that "Optimism reigns supreme and the driving beat makes anything seem possible" and highlighted the "spectacular finale with chimes, saxes and guitars thundering along".[108] Record World said that "Guy Lombardo now has a rock counterpart as Harrison gallops in with a future New fears perennial."[109]

In the 1978 edition of The Beatles: An Illustrated Record, Roy Carr and Tony Tyler dismissed the song as "meticulously-played emptiness, a charmless reworking of the traditional peal o' bells" before concluding: "A pox on it."[110] Writing in his 1977 book The Beatles Forever, Nicholas Schaffner rued that "the exquisite, painstaking arrangements" of Harrison's earlier albums were absent from Dark Horse, and labelled "Ding Dong" "a string of greeting-card clichés with trite music to match".[95]

Retrospective assessments and legacy

In his song review for AllMusic, Lindsay Planer writes of "Ding Dong, Ding Dong": "While arguably simplistic, both lyrics and tune boast Harrison's trademark optimism, especially during the affable and repeated chorus of 'Ring out the old/Ring in the new/Ring out the false/Ring in the true.'"[30] Harrison biographer Alan Clayson acknowledges the traditional pop merits of the song while explaining its underachievement: "With a chirpy-chirpy cheapness worthy of Red Rose Speedway, 'Ding Dong, Ding Dong' had all the credentials of a Yuletide smash but none that actually grabbed the public."[111] Writing for Goldmine in January 2002, Dave Thompson described it as "sweetly simplistic" and "a sterling stab at a Christmas anthem … that deserved far better than its low Top 40 chart placings in the U.S. and Britain".[82]

In his 2010 book on Harrison for the Praeger Singer-Songwriter series, Ian Inglis comments that the song had neither the "overt political message" of Lennon's Christmas single nor the "unashamed commercialism" of Paul McCartney's "Wonderful Christmastime", and writes that "Ding Dong"'s "somewhat halfhearted festive appeal" seems out of place on Dark Horse.[15] Simon Leng views the song as an "intermittently amusing rocker", but with the perilous state of Harrison's voice on the recording, "Ding Dong" would have benefited from "hibernating another winter".[42] Author Robert Rodriguez opines that whereas Harrison's "rough-hewn" vocals on "Dark Horse" had enhanced that song, his "Father Time impression" did nothing for "Ding Dong".[112]

Among reviews of the 2014 Apple Years reissue of Dark Horse, Paste's Robert Ham refers to the song as "a Christmas anthem … that is as infectious as McCartney's 'Wonderful Christmastime' and as globally minded as Lennon's 'Happy Xmas (War Is Over)'".[113] Conversely, Paul Trynka of Classic Rock singles out "Ding Dong, Ding Dong" as the one song that "embarrasses" on an album that is otherwise "packed with beautiful, small-scale moments". Trynka labels it "George's own Frog Chorus", with reference to McCartney's 1984 children's song, "We All Stand Together", and adds: "its clunking glam evokes those horrible 70s TV shows where DJs drool over dollybirds in hotpants."[114][115]

In December 1999, while promoting his album I Wanna Be Santa Claus, Starr hosted a Christmas-themed radio show for New York's MJI Broadcasting, during which he featured "Ding Dong" along with the singles by Lennon and McCartney, as well as seasonal recordings by Spector and by a selection of Motown artists.[116] Harrison's track still receives airplay over the Christmas–New Year period.[13] Unlike "Happy Xmas", however, and, to a lesser extent, "Wonderful Christmastime",[15][nb 9] "Ding Dong" never achieved the status of a perennial holiday classic.[13]

Promo clip

Harrison compiled a 16mm colour film for "Ding Dong, Ding Dong", the first time he made a promotional clip for one of his singles.[118] The film was little seen at the time of release;[11] it was first broadcast in January 1975, on UK television, and then on the French network TF1's show Midi Premiere in May that year.[119] The video was issued officially on disc eight of Harrison's Apple Years 1968–75 box set in September 2014.[120] Described as "a hoot" by Robert Rodriguez,[121] it conveys what Harrison deemed the "comical" aspect of the song.[122] Leng describes the clip as "sporadically amusing" and says of its content: "As the audiences at the Dark Horse Tour concerts were about to discover, the only 'old' that he wanted to 'ring out' was the Beatles."[42]

Harrison appears in a range of Beatles-related costumes while miming to the track.[42] His attire in these scenes represents a chronology of periods in the band's career[118] – starting with the Hamburg-era black leathers, followed by 1963 mop-top wig and grey collarless suit, and then the iconic Sgt. Pepper uniform from 1967.[11][123] During these scenes, he plays a mix of guitars, including his famous Rickenbacker 12-string,[123] as used in the Beatles' 1964 film A Hard Day's Night,[118] and the Gibson Les Paul (christened "Lucy")[124] that Clapton had used on the recording of "While My Guitar Gently Weeps" in September 1968.[125] The Sgt. Pepper portion shows Harrison playing a tuba while, behind him, an Indian man plays a sitar.[123] Harrison also re-creates Lennon and Ono's Two Virgins album cover, by appearing naked save for an acoustic guitar and a pair of furry boots.[118] Another change of costume and instrument, to denims and dobro, supports his stated rejection during the tour of early-'70s era, "Bangla Desh George".[118][126]

Harrison is also seen walking around the grounds of Friar Park.[118][123] In these scenes, he wears scruffy, present-day attire that represents "his own, new identity", according to Leng, who likens Harrison's appearance to the character on the cover of Jethro Tull's Aqualung album.[127] Harrison mimes the final choruses inside the house, filmed in close-up and surrounded by a cast of "dwarfs, gnomes and other Pythonesque characters".[42] At the end of the clip, he is seen at the flagpole on the roof of the house, replacing a pirate standard with his yellow-and-red Om flag[118] – a gesture that was the opposite of Boyd's when she learned of Harrison's affair with Maureen Starkey.[128][nb 10] The video was directed by Harrison and filmed by Nick Knowland.[131]

Personnel

Adapted from Harrison's original handwritten credits, as reproduced in the 2014 Dark Horse CD booklet:[53]

- George Harrison – vocals, 12-string acoustic guitar, slide guitars,[30] organ, clavinet, percussion, backing vocals

- Tom Scott – saxophones, horn arrangement

- Gary Wright – piano

- Klaus Voormann – bass

- Jim Keltner – drums

- Ringo Starr – drums

- Ron Wood – electric guitar

- Alvin Lee – electric guitar

- Mick Jones – acoustic guitar

- uncredited – female choir[15]

Chart positions

| Chart (1974–75) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Belgian Ultratop Singles Chart[89] | 12 |

| Canadian RPM 100[132] | 63 |

| Dutch MegaChart Singles[88] | 10 |

| Japanese Oricon Singles Chart[133] | 68 |

| South African Springbok Singles Chart[134] | 20 |

| UK Singles Chart[83] | 38 |

| US Billboard Hot 100[84] | 36 |

| US Cash Box Top 100[66] | 36 |

| US Record World Singles Chart[135] | 49 |

| West German Media Control Chart[136] | 31 |

Notes

- Harrison detailed his more intense feelings on the end of their marriage in another song, "So Sad",[35] which he also recorded at this time.[13]

- With the winding down of Apple Records from 1973, Harrison spent considerable time trying to set up his own record company, Dark Horse.[40] Like his former Beatles bandmates, Harrison remained an Apple artist until the expiration of his EMI-affiliated recording contract in January 1976, at which point he signed with Dark Horse.[41]

- In December 1972, Apple had reissued the 1963 Christmas disc as Phil Spector's Christmas Album,[48] a release that brought the work overdue recognition and commercial success, especially in Britain.[49]

- For these keyboard and percussion parts, Harrison credited himself as, variously, Hari Georgeson, Jai Raj Harisein and P. Roducer,[53] which were pseudonyms he also used for his many contributions to Splinter's album.[54]

- In addition to setting up the new record label and finishing the Splinter and Shankar albums,[57] Harrison was trying to find a distributor for Apple Films' Little Malcolm (1974) and overseeing a new project, Ravi Shankar's Music Festival from India.[58]

- Harrison had told Geffen that he would be retaining much of his original guide vocal,[11] which was recorded during a period when, according to Boyd and to Harrison's later admission, his overindulgence with alcohol and cocaine was common.[63][64]

- Despite the message of some of the songs on Dark Horse, particularly in his reinterpretation of the Everly Brothers' "Bye Bye, Love", Harrison remained good friends with Boyd and Clapton.[79][80] Boyd recalls him joining her and Clapton at the latter's house in England for their Christmas Day meal in December 1974.[81]

- A similarly late release for Lennon and Ono's "Happy Xmas (War Is Over)" in December 1971 had limited that single's commercial success in America.[86] While not eligible for the Billboard Hot 100, since the magazine compiled a separate Christmas Singles listing in 1971, "Happy Xmas" peaked at number 36 on Cash Box's Top 100 singles chart, as did "Ding Dong" on the same chart three years later.[87]

- McCartney's song was a top-ten hit in the UK over 1979–80, but failed to chart in the US.[117]

- The choice of flag on any given day during this period was indicative of his level of spiritual devotion.[129] Author Gary Tillery describes the two options as "a banner featuring OM in Sanskrit when he felt in tune with his [spiritual] goals … a skull and crossbones when he did not".[130]

References

- Badman, p. 144.

- Huntley, p. 46.

- Clayson, p. 299.

- George Harrison, p. 208.

- Boyd, pp. 144, 145.

- Olivia Harrison, p. 268.

- Snow, pp. 24–25.

- Greene, pp. 165, 171.

- George Harrison, p. 37.

- Huntley, p. 123.

- Madinger & Easter, p. 444.

- George Harrison, p. 280.

- Spizer, p. 264.

- George Harrison, p. 279.

- Inglis, p. 46.

- Allison, p. 140.

- George Harrison, p. 162.

- Clayson, pp. 322–23.

- Madinger & Easter, pp. 434, 444.

- Leng, pp. 144–46, 148, 149.

- Greene, pp. 200–02.

- Inglis, p. 43.

- Clayson, pp. 306, 324.

- Rodriguez, p. 142.

- Leng, p. 150.

- Leng, pp. 147, 153.

- Steven Rosen, "George Harrison", Rock's Backpages, 2008 (subscription required).

- Kahn, p. 186.

- Leng, p. 153.

- Lindsay Planer, "George Harrison 'Ding Dong, Ding Dong'", AllMusic (retrieved 19 July 2016).

- Inner sleeve credits, Dark Horse LP (Apple Records, 1974; produced by George Harrison).

- Doggett, pp. 208–09.

- O'Dell, p. 266.

- Boyd, p. 177.

- Inglis, p. 45.

- Leng, pp. 153–54, 165.

- Tillery, p. 112.

- Madinger & Easter, pp. 442, 444.

- Clayson, p. 346.

- Woffinden, pp. 74, 85.

- Clayson, pp. 345–46.

- Leng, p. 154.

- Leng, pp. 153–54.

- Clayson, pp. 343, 479.

- Dennis MacDonald, "Phil Spector A Christmas Gift for You from Phil Spector", AllMusic (retrieved 28 December 2012).

- Clayson, p. 343.

- Williams, p. 17.

- Spizer, p. 342.

- Williams, p. 166.

- Schaffner, pp. 159–60.

- Stephen Holden, "George Harrison, Living in the Material World" Archived 3 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Rolling Stone, 19 July 1973, p. 54 (retrieved 18 July 2016).

- Michael Gross, "George Harrison: How Dark Horse Whipped Up a Winning Tour", Circus Raves, March 1975; available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- "George's original [inner] sleeve design for the album Dark Horse" (sample album credits), Dark Horse CD booklet (Apple Records, 2014; produced by George Harrison), p. 8.

- Schaffner, p. 179.

- Madinger & Easter, pp. 442–43.

- The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 44.

- Kahn, pp. 183, 186.

- Leng, pp. 147–48, 155.

- David Cavanagh, "George Harrison: The Dark Horse", Uncut, August 2008, pp. 43–44.

- Mat Snow, "George Harrison: Quiet Storm", Mojo, November 2014, p. 72.

- Tillery, p. 114.

- Leng, p. 115.

- Boyd, pp. 175–76.

- Allison, p. 7.

- Leng, pp. 153, 154.

- Spizer, p. 269.

- Castleman & Podrazik, p. 144.

- Inglis, p. 49.

- Timothy White, "George Harrison: Reconsidered", Musician, November 1987, p. 65.

- Badman, pp. 142, 146.

- Spizer, pp. 265, 269.

- Spizer, pp. 269, 270.

- Madinger & Easter, p. 443.

- Spizer, p. 265.

- Woffinden, pp. 84–85.

- Spizer, pp. 265, 267.

- Huntley, pp. 118, 121.

- Badman, p. 139.

- Greene, pp. 208–09.

- The Editors of Rolling Stone, pp. 44, 46.

- Boyd, pp. 187–88.

- Dave Thompson, "The Music of George Harrison: An album-by-album guide", Goldmine, 25 January 2002, p. 17.

- "Artist: George Harrison", Official Charts Company (retrieved 11 April 2014).

- "George Harrison > Charts & Awards > Billboard Singles", AllMusic (retrieved 11 April 2014).

- Badman, pp. 144, 151.

- Madinger & Easter, p. 66.

- Spizer, pp. 61, 269.

- "George Harrison – Ding Dong, Ding Dong", dutchcharts.nl (retrieved 10 July 2013).

- "George Harrison – Ding Dong, Ding Dong", ultratop.be (retrieved 10 July 2013).

- Rodriguez, p. 128.

- Schaffner, pp. 188, 191.

- Badman, p. 473.

- Joe Marchese, "Review: The George Harrison Remasters – 'The Apple Years 1968–1975'", The Second Disc, 23 September 2014 (retrieved 28 September 2014).

- Peter Doggett, "George Harrison: The Apple Years", Record Collector, April 2001, p. 39.

- Schaffner, p. 178.

- Kahn, p. 183.

- Leng, pp. 154, 166.

- The Editors of Rolling Stone, pp. 44, 126, 129.

- Rodriguez, pp. 58–59, 238.

- Clayson, pp. 343−44.

- Bob Woffinden, "George Harrison: Dark Horse", NME, 21 December 1974; available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- Leng, p. 158.

- Spizer, p. 260.

- Chris Hunt (ed.), NME Originals: Beatles – The Solo Years 1970–1980, IPC Ignite! (London, 2005), p. 92.

- Jim Miller, "Dark Horse: Transcendental Mediocrity", Rolling Stone, 13 February 1975, pp. 75–76.

- Mike Jahn, "The Lighter Side: George Harrison, Dark Horse", High Fidelity, April 1975, p. 101.

- Bob Kirsch (ed.), "Top Single Picks", Billboard, 4 January 1975, p. 47 (retrieved 21 November 2014).

- "Cash Box Singles Reviews", Cash Box, 4 January 1975, p. 11 (retrieved 9 December 2021).

- "Hits of the Week" (PDF). Record World. 4 January 1975. p. 1. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- Carr & Tyler, p. 113.

- Clayson, p. 344.

- Rodriguez, pp. 201, 411.

- Robert Ham, "George Harrison: The Apple Years: 1968–1975 Review", Paste, 24 September 2014 (retrieved 28 September 2014).

- Paul Trynka, "George Harrison The Apple Years 1968–75", Classic Rock, November 2014, p. 105.

- Paul Trynka, "George Harrison: The Apple Years 1968–75", TeamRock, 8 October 2014 (retrieved 27 November 2014).

- Badman, p. 346.

- Rodriguez, p. 191.

- Badman, p. 146.

- Pieper, pp. 146, 344.

- Kory Grow, "George Harrison's First Six Studio Albums to Get Lavish Reissues" Archived 23 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, rollingstone.com, 2 September 2014 (retrieved 28 September 2014).

- Rodriguez, p. 201.

- Badman, pp. 144, 146.

- Pieper, p. 146.

- Clayson, p. 252.

- MacDonald, p. 264fn.

- The Editors of Rolling Stone, pp. 126, 129.

- Leng, pp. 143, 154.

- Boyd, pp. 174–75.

- Greene, p. 172.

- Tillery, p. 91.

- Joe Marchese, "Give Me Love: George Harrison’s 'Apple Years' Are Collected On New Box Set", The Second Disc, 2 September 2014 (retrieved 28 September 2014).

- "RPM 100 Singles, 22 February 1975" Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Library and Archives Canada (retrieved 11 April 2014).

- "George Harrison: Chart Action (Japan)" Archived 23 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine, homepage1.nifty.com (retrieved 11 April 2014).

- "SA Charts 1969–1989 Songs (C–D)", South African Rock Lists, 2000 (retrieved 30 December 2012).

- "The Singles Chart", Record World, 1 February 1975, p. 35.

- "Single – George Harrison, Ding Dong, Ding Dong", charts.de (retrieved 3 January 2013).

Sources

- Dale C. Allison Jr, The Love There That's Sleeping: The Art and Spirituality of George Harrison, Continuum (New York, NY, 2006; ISBN 978-0-8264-1917-0).

- Keith Badman, The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970–2001, Omnibus Press (London, 2001; ISBN 0-7119-8307-0).

- Pattie Boyd (with Penny Junor), Wonderful Today: The Autobiography, Headline Review (London, 2007; ISBN 978-0-7553-1646-5).

- Roy Carr & Tony Tyler, The Beatles: An Illustrated Record, Trewin Copplestone Publishing (London, 1978; ISBN 0-450-04170-0).

- Harry Castleman & Walter J. Podrazik, All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975, Ballantine Books (New York, NY, 1976; ISBN 0-345-25680-8).

- Alan Clayson, George Harrison, Sanctuary (London, 2003; ISBN 1-86074-489-3).

- Peter Doggett, You Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the Breakup, It Books (New York, NY, 2011; ISBN 978-0-06-177418-8).

- The Editors of Rolling Stone, Harrison, Rolling Stone Press/Simon & Schuster (New York, NY, 2002; ISBN 0-7432-3581-9).

- Joshua M. Greene, Here Comes the Sun: The Spiritual and Musical Journey of George Harrison, John Wiley & Sons (Hoboken, NJ, 2006; ISBN 978-0-470-12780-3).

- George Harrison, I Me Mine, Chronicle Books (San Francisco, CA, 2002 [1980]; ISBN 0-8118-3793-9).

- Olivia Harrison, George Harrison: Living in the Material World, Abrams (New York, NY, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4197-0220-4).

- Elliot J. Huntley, Mystical One: George Harrison – After the Break-up of the Beatles, Guernica Editions (Toronto, ON, 2006; ISBN 1-55071-197-0).

- Ian Inglis, The Words and Music of George Harrison, Praeger (Santa Barbara, CA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-313-37532-3).

- Ashley Kahn (ed.), George Harrison on George Harrison: Interviews and Encounters, Chicago Review Press (Chicago, IL, 2020; ISBN 978-1-64160-051-4).

- Simon Leng, While My Guitar Gently Weeps: The Music of George Harrison, Hal Leonard (Milwaukee, WI, 2006; ISBN 1-4234-0609-5).

- Ian MacDonald, Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties, Pimlico (London, 1998; ISBN 0-7126-6697-4).

- Chip Madinger & Mark Easter, Eight Arms to Hold You: The Solo Beatles Compendium, 44.1 Productions (Chesterfield, MO, 2000; ISBN 0-615-11724-4).

- Chris O'Dell (with Katherine Ketcham), Miss O'Dell: My Hard Days and Long Nights with The Beatles, The Stones, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, and the Women They Loved, Touchstone (New York, NY, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4).

- Jörg Pieper, The Solo Beatles Film & TV Chronicle 1971–1980, Premium Förlag (Stockholm, 2012; ISBN 978-1-4092-8301-0).

- Robert Rodriguez, Fab Four FAQ 2.0: The Beatles' Solo Years, 1970–1980, Backbeat Books (Milwaukee, WI, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4).

- Nicholas Schaffner, The Beatles Forever, McGraw-Hill (New York, NY, 1978; ISBN 0-07-055087-5).

- Mat Snow, The Beatles Solo: The Illustrated Chronicles of John, Paul, George, and Ringo After the Beatles (Volume 3: George), Race Point Publishing (New York, NY, 2013; ISBN 978-1-937994-26-6).

- Bruce Spizer, The Beatles Solo on Apple Records, 498 Productions (New Orleans, LA, 2005; ISBN 0-9662649-5-9).

- Gary Tillery, Working Class Mystic: A Spiritual Biography of George Harrison, Quest Books (Wheaton, IL, 2011; ISBN 978-0-8356-0900-5).

- Richard Williams, Phil Spector: Out of His Head, Omnibus Press (London, 2003; ISBN 978-0-7119-9864-3).

- Bob Woffinden, The Beatles Apart, Proteus (London, 1981; ISBN 0-906071-89-5).