Faster (George Harrison song)

"Faster" is a song by English rock musician George Harrison from his self-titled 1979 studio album. The song was inspired by Harrison's year away from music-making in 1977, during which he travelled with the Formula 1 World Championship, and by his friendship with racing drivers such as Jackie Stewart and Niki Lauda. Although equally applicable to other professions, the lyrics address the difficulties of achieving and maintaining success in the field of motorsport, particularly Formula 1.

| "Faster" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

UK picture disc | ||||

| Single by George Harrison | ||||

| from the album George Harrison | ||||

| B-side | "Your Love Is Forever" | |||

| Released | 13 July 1979 | |||

| Genre | Pop rock | |||

| Length | 4:46 | |||

| Label | Dark Horse | |||

| Songwriter(s) | George Harrison | |||

| Producer(s) | George Harrison, Russ Titelman | |||

| George Harrison singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| George Harrison track listing | ||||

10 tracks | ||||

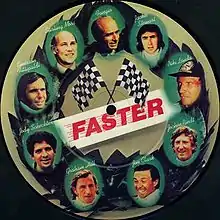

In Britain, "Faster" was issued as the third single from George Harrison, and was available on a picture disc depicting the faces of several past world champion drivers. The single raised funds for a cancer research fund set up by Swedish driver Gunnar Nilsson in 1978. It also commemorated Nilsson's countryman Ronnie Peterson, who died as a result of injuries sustained during the 1978 Italian Grand Prix. Harrison made a video of the song, during which he performs the track in the back of a car chauffeured by Stewart.

Background and inspiration

"Are you going to write a song about motor racing, George?" was a question I was asked a lot by various people from the Grand Prix teams … So I did "Faster" to write about something specific, as a challenge.[1]

– George Harrison, 1979

George Harrison located the start of his enthusiasm for car and motorbike racing to his attending local events in Liverpool as a boy.[2][3] He especially recalled the 1955 British Grand Prix, held at Aintree,[4] and the dominance of Mercedes teammates Juan Manuel Fangio and Stirling Moss.[5][6] He said that when the Beatles achieved fame in the 1960s, he was conscious of other celebrities, like Formula 1 driver Jackie Stewart, who had long hair; he was also drawn to reading Stewart say that amid his international racing commitments, he would search out the latest Beatles record.[7] Along with his bandmates, Harrison attended the Monaco Grand Prix in May 1966 and met Stewart.[8] He was also present for the 1971 event, a year after the Beatles' break-up, by which time Stewart had become a dominant competitor, soon to win his second world championship.[9]

During 1977, Harrison attended many of the races on the Formula 1 calendar as a break from songwriting and recording.[10][11] He first went to Long Beach, California in April, hoping to get good tickets for the upcoming United States Grand Prix West; there, he met motorbike world champion Barry Sheene, who was considering a career move into car racing.[12] Over the course of the 1977 season, Harrison befriended racing drivers such as Niki Lauda, Emerson Fittipaldi, Jody Scheckter and Mario Andretti,[12] and became close to Stewart,[13] who continued to be associated with the sport in a media role.[14][nb 1] After the United States Grand Prix in October, a conversation with Lauda encouraged Harrison to resume songwriting;[15][16] he wrote "Blow Away" as a song "that Niki-Jody-Emerson and the gang could enjoy".[17]

In addition to attracting further media attention to Formula 1,[18] Harrison's presence at the grands prix led to constant questions about whether he intended to write a song about the sport.[1] He subsequently wrote "Faster", drawing inspiration from Lauda's successful comeback from his near-fatal crash at the Nürburgring the previous year.[19] He also credited Stewart as an inspiration for the song,[20] which shares its title with that of Stewart's autobiography, Faster: A Racer's Diary.[21] In Harrison's 1980 autobiography I, Me, Mine, his handwritten lyrics are dated 20 November 1977.[22] Discussing the song in the book, Harrison recalls that after adopting Stewart's title, he first wrote the chorus, beginning with the lines "Faster than a bullet from a gun / He is faster than everyone".[1]

Composition

"Faster" is in the pop rock style typical of the songs on the George Harrison album.[23] Music journalist Lindsay Planer describes the released version as an "upbeat and driving rocker".[24] According to Harrison's notes reproduced in I, Me, Mine, the chorus uses the chords A, C, G, D, F♯ minor and B minor.[25] The verses employ syncopated phrasing[26] and use the chords D, Asus4, B minor and G.[25][nb 2]

Harrison wrote the majority of the lyrics in such a way that the message is not limited solely to motor racing.[28][26][29] In the view of author Robert Rodriguez, the lyrics to "Faster" are as applicable to a Formula 1 driver as they are to "anyone embarking on a career in the limelight, say, a rock star".[30] Harrison describes a racing driver's career path as a "life in circuses"[28] and sings of a driver's wife having to hold back her fears about the sport's inherent danger.[26] He also sings of the vicarious thrill for spectators,[28] and of the jealousy among sporting rivals.[24]

In I, Me Mine, Harrison says that only the inclusion of the word "machinery" and the addition of sound effects on the recording provide an obvious link to motor racing. He also states: "I have a lot of fun with many of the Formula One drivers and their crews – and they have enabled me to see things from a very different angle than the music business I am normally involved with."[1]

Recording

Recording for "Faster" and other songs on George Harrison began in April 1978,[31][32] after Harrison and his girlfriend, Olivia Arias, returned from the United States West Grand Prix.[33][34] The sessions took place at his home studio, FPSHOT, in Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire,[35] and were co-produced by Russ Titelman.[36] On 25 April, Harrison took time out from recording to drive a Formula 1 car for the first time, at the Brands Hatch circuit in Kent.[37] He drove a Surtees TS19 after Sheene, who was being given a private test session by team owner John Surtees,[38] arranged for Harrison to have a lap in the car.[39]

The recording has a symphonic pop sound similar to Harrison's 1970 triple album All Things Must Pass and his 1987 collaboration with Jeff Lynne "When We Was Fab".[40] Harrison played all the guitars on the track. These included 12-string acoustic rhythm parts, which author Simon Leng likens to the "chiming" guitars on "My Sweet Lord", and electric lead parts,[41] including slide guitars.[24] He also made a rare contribution on bass guitar,[42] filling the role taken by Willie Weeks on the rest of the album.[43] Arranged by Del Newman,[44] orchestral strings were overdubbed at AIR Studios in London in October 1978.[45]

The track is punctuated with contemporary F1 sounds. It opens with the cars revving up and then starting a race.[24][26] According to authors Chip Madinger and Mark Easter, Harrison captured these sounds from grands prix he attended in 1977,[42] while Beatles biographer Bill Harry states that the race start originates from the 1978 British Grand Prix at Brands Hatch.[46]

Release

The title of Harrison's album was initially Faster, after his F1 tribute song, until he opted for George Harrison.[45] It was issued on his Dark Horse record label on 14 February 1979,[47] with "Faster" sequenced as the opening track on side two of the LP.[48] In the album credits, Harrison dedicated "Faster" to "the Entire Formula One Circus" and to the memory of Ronnie Peterson,[49] who had died in September 1978 following his opening-lap crash in the Italian Grand Prix.[50] The credits and the song's lyrics filled one side of the inner sleeve,[49] along with a photo of Harrison and Stewart taken at the 1978 British Grand Prix.[44][nb 3]

Harrison continued to be associated with Formula 1 through much of the 1979 season.[18][52] While attending the Brazilian Grand Prix in February, he corrected a journalist who assumed that the whole album was inspired by Formula 1, telling him, "Only one out ten. It's called 'Faster' ..."[18] He also accurately predicted that Scheckter would win the 1979 drivers title for Ferrari.[53] When asked about his favourite songs on George Harrison in a Rolling Stone interview later that month, Harrison said he was especially pleased with "Faster", because he had satisfied his racing friends' requests that he write a song about the sport, and he had done it in a way that "wasn't just corny".[54] He added that "It's easy to write about V-8 engines and vroom vroom – [but] that would have been bullshit", and he was pleased that the lyrics could apply to one particular driver or all the drivers, or even to the Beatles, with "the jealousies and things like that", if the sound effects were removed.[55][56]

Backed by "Your Love Is Forever", the song was released as a charity single in the UK on 13 July,[57] to benefit the Gunnar Nilsson Cancer Fund.[58][59] The fund was started by Swedish driver Gunnar Nilsson in 1978, during the final weeks before his death through cancer, to finance a cancer treatment unit in London's Charing Cross Hospital.[60] In early June, Harrison took part in the Gunnar Nilsson Memorial Trophy weekend at Donington Park circuit.[61] In one event, he drove Moss's Lotus 18 from the early 1960s;[39] in another, he was a celebrity entrant in the BMW M1 Procar Championship race.[62][nb 4] During their joint TV interview to promote the cause, Stewart said of Harrison, "he really is the master of going faster" and described "Faster" as a "great song about motor racing", while Harrison called himself a "privileged hangers-on club member" and praised Nilsson's achievements in establishing the memorial fund.[63][nb 5]

The single was also available as a limited-edition picture disc,[42] marking the first time that a record by a former Beatle was issued in this new format.[20][58] The A-side of the disc depicted the faces of former drivers Fangio, Moss, Stewart, Jim Clark, Graham Hill and Jochen Rindt, and contemporary competitors Lauda, Fittipaldi and Scheckter.[46] "Faster" failed to chart in the UK.[65] Rodriguez attributes this partly to the local music scene being "markedly different" from the US, where Harrison's 1979 releases achieved considerably more success.[66]

Music video

Harrison made a promotional film for the single, which includes footage he shot at the Brazilian Grand Prix in São Paulo in February 1979.[42] The film alternates between these and other racing scenes and clips of Harrison miming to the song while seated in the back of a limousine,[42] with Stewart acting as his chauffeur.[46][67] The latter scenes were filmed on 28 May, following the weekend of the 1979 Monaco Grand Prix,[46] which Harrison attended with Ringo Starr.[68][nb 6]

The video was first broadcast in France on the TF1 programme IT1 20H.[21] In the UK, it aired on ITV's World of Sport on 18 August.[69][71] In 2004, the "Faster" video was included on the DVD accompanying Harrison's Dark Horse Years reissues.[21]

Critical reception and legacy

In his album review for the NME, Harry George recognised "Faster" as a song that "breaks new ground for Harrison, focussing on the twin pressures of motor racing: danger and public acclaim". George admired the track as "compassionate yet unpretentious, cruising chunkily in third gear".[72] Bob Spitz of The Washington Post said that Harrison's self-titled album re-established him as a "first-rate composer" and paired the song with "Blow Away" as two "bright and imaginative tunes which should find wide appeal among top 40 audiences".[73] Less impressed with George Harrison, Village Voice critic Robert Christgau singled out "Faster" as the record's only good song and one "about a kind of stardom", adding: "He remembers!"[74]

NME critic Bob Woffinden welcomed the changes evident in Harrison after his year off pursuing extracurricular interests, and said that with "Faster" he had "succeeded admirably" in writing an effective tribute to F1.[75] In a more recent review, for AllMusic, Lindsay Planer praises Harrison's acoustic and electric guitar playing on the track and cites it as a worthy example of why proponents of George Harrison recognise it as a fine album.[24]

I know that racing is to a lot of people, dopey, maybe from a spiritual point of view. Motor cars – polluters, killers, maimers, noisemakers. Good racing, though, involves heightened awareness for the competitors. Those drivers have to be so together in their concentration and the handful of them who are the best have had some sort of expansion of their consciousness.[76]

– Harrison in I, Me, Mine, 1980

Writing for Goldmine magazine in 2002, Dave Thompson said that "Faster" documented Harrison's "devotion to motor racing" and had become an "anthem of sorts" for Formula 1.[77] The song established a public connection between Harrison and racing, particularly F1, that lasted until his death in 2001. His involvement extended to sponsoring motorcyclist Steve Parrish[39] and financing the early career of Damon Hill.[78] He remained a lifelong friend of Stewart, Fittipaldi and Barry Sheene.[79] Harrison became known for having offered Sheene a cash incentive not to return to competitive racing and risk further injury.[80][nb 7] He contributed to The Sunday Times' November 2000 supplement titled The Formula One Handbook.[82]

In Martin Scorsese's 2011 documentary film George Harrison: Living in the Material World, film-maker Terry Gilliam comments on how car and bike racing, film production and music were equal passions in Harrison's life, and on the apparent contradiction these interests presented with his spiritual side.[83][nb 8] Stewart believes he identified with the heightened senses required for driving on the absolute limit of human and mechanical endurance, as this sensory quality also informs a top musician's artistry.[6][85] Discussing the appeal for Harrison, car designer Gordon Murray draws parallels between the best drivers' ability to process and slow down incoming sensory information and the discipline used in meditation.[86]

Personnel

According to author Simon Leng:[87]

- George Harrison – vocals, 12-string acoustic guitars, slide guitars, electric guitar, bass, backing vocals

- Neil Larsen – piano

- Andy Newmark – drums

- Ray Cooper – tambourine

- Del Newman – string arrangement

Notes

- Stewart later said he was amazed at Harrison's knowledge of motor racing. Harrison was equally astounded by Stewart's grasp of every detail of the Beatles' history.[11]

- According to author Simon Leng, Harrison's song "Mo", which he recorded in early 1977 as a birthday tribute to Warner Bros. Records president Mo Ostin, is a "reverse version of the 'Faster' chord sequence".[27]

- Among those connected with racing that Harrison listed under "Thanks to" were Sheene;[51] Bernie Ecclestone, Lauda's boss at the Brabham team; Walter Wolf, owner of Wolf Racing, Scheckter's former team; and "Brands Hatch Timekeepers".[49]

- In biographer Gary Tillery's description, it was a "highlight of [Harrison's] life" to be allowed to drive the car, which Moss had driven to victory in the 1960 Monaco Grand Prix.[4]

- Harrison also participated in the Gunnar Nilsson Endurance Drive,[64] an earlier fundraiser for Nilsson's cancer research initiative.[39] A 24-hour event, it was organised by Matlins, a Henley-based sportscar retailer,[39] and held at the Silverstone circuit on 9 January.[64]

- Harrison and Starr were interviewed before the Monaco race by Stewart[69] for the US programme Wide World of Sports.[70] Harrison correctly picked Scheckter as the likely race winner, while Starr chose Fangio, despite the latter having retired in 1959.[14]

- Harrison wrote a song about Sheene, although it was never released.[51] In 1996, he performed "Here Comes Emerson" (sung to the tune of "Here Comes the Sun") at Friar Park for inclusion in a Brazilian TV show,[81] with the lyrics altered to celebrate Fittipaldi's recovery from a serious injury.[51]

- In his 1979 album review for High Fidelity, Sam Sutherland recognised a "juxtaposition of the chic with the earnest" in the LP's inner sleeve – specifically, the "photo of an older, tweedier, but still shaggy Harrison strolling through the paddock of a grand prix race circuit, under which is printed his usual salutation, 'Hare Krishna'".[84]

References

- Harrison 2002, p. 370.

- Harrison 2002, p. 73.

- Kahn 2020, p. 267.

- Tillery 2011, p. 119.

- Harry 2003, pp. 272–73.

- Harrison 2011, p. 334.

- Harrison 2002, pp. 72–73.

- Stewart, Jackie (December 2011). "The Greatest Party That Never Happened ..." Motor Sport. pp. 52–53.

- Clayson 2003, pp. 306–07.

- Harrison 2002, pp. 74, 378.

- Rodriguez 2010, p. 340.

- Harrison 2002, p. 74.

- Woffinden 1981, p. 104.

- Pieper 2012, p. 278.

- Kahn 2020, p. 269.

- Snow 2013, p. 64.

- Harrison 2002, p. 378.

- Clayson 2003, p. 366.

- Clayson 2003, pp. 366–67.

- Harry 2003, p. 171.

- Pieper 2012, p. 275.

- Harrison 2002, p. 372.

- Inglis 2010, p. 71.

- Planer, Lindsay. "George Harrison 'Faster'". AllMusic. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Harrison 2002, p. 371.

- Clayson 2003, p. 367.

- Leng 2006, p. 277.

- Inglis 2010, p. 69.

- Tillery 2011, p. 121.

- Rodriguez 2010, p. 177.

- Kahn 2020, p. 268.

- Huntley 2006, pp. 156, 164.

- Badman 2001, p. 221.

- Harry 2003, p. 82.

- Leng 2006, pp. 199–201.

- Inglis 2010, p. 66.

- Snow 2013, pp. 64–65.

- Harry 2003, pp. 340–41.

- Clayson 2003, p. 365.

- MacFarlane 2019, p. 115.

- Leng 2006, p. 206.

- Madinger & Easter 2000, p. 458.

- Clayson 2003, p. 369.

- Harry 2003, p. 188.

- Madinger & Easter 2000, p. 457.

- Harry 2003, p. 172.

- Badman 2001, p. 229.

- Madinger & Easter 2000, p. 635.

- George Harrison (LP sleeve). George Harrison. Dark Horse Records. 1979.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - UPI (Milan) (12 September 1978). "Ronnie Peterson Dies from Crash". The Morning Record and Journal. p. 10. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- Harry 2003, p. 341.

- Inglis 2010, p. 72.

- Pieper 2012, pp. 272, 278.

- Kahn 2020, pp. 279–80.

- Brown, Mick (19 April 1979). "A Conversation with George Harrison". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- Kahn 2020, p. 280.

- Madinger & Easter 2000, p. 632.

- Badman 2001, p. 234.

- Woffinden 1981, p. 106.

- Hughes, Mark (September 1997). "Once in a Lifetime ..." Motor Sport. p. 43. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- Pieper 2012, pp. 278–79.

- Petrány, Máté (11 February 2020). "Watch Jackie Stewart and ex-Beatle George Harrison get surprised by young Piquet". Hagerty Media. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- Pieper 2012, p. 279.

- Pieper 2012, p. 272.

- Huntley 2006, p. 167.

- Rodriguez 2010, pp. 286, 288.

- Rodriguez 2010, pp. 177, 288.

- Badman 2001, pp. 232, 233.

- Harry 2003, p. 83.

- Badman 2001, p. 232.

- Badman 2001, p. 235.

- George, Harry (24 February 1979). "George Harrison George Harrison (Dark Horse)". NME. p. 22.

- Spitz, Robert S. (4 March 1979). "George Harrison on the Move". The Washington Post. p. A1. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- Christgau, Robert (1981). "George Harrison: George Harrison". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 0899190251. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- Woffinden 1981, pp. 104, 106.

- Harrison 2002, pp. 74–75.

- Thompson, Dave (25 January 2002). "The Music of George Harrison: An album-by-album guide". Goldmine. p. 18.

- Harrison 2011, p. 336.

- Harry 2003, pp. 176–77, 340–41.

- Clayson 2003, p. 394.

- Madinger & Easter 2000, p. 487.

- Clayson 2003, pp. 441–42.

- Harrison 2011, p. 320.

- Sutherland, Sam (May 1979). "Records: George Harrison". High Fidelity. p. 125.

- Runtagh, Jordan (29 November 2016). "10 Things You Didn't Know George Harrison Did". rollingstone.com. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Harrison 2011, p. 338.

- Leng 2006, pp. 205–06.

Sources

- Badman, Keith (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970–2001. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-8307-6.

- Clayson, Alan (2003). George Harrison. London: Sanctuary. ISBN 1-86074-489-3.

- The Editors of Rolling Stone (2002). Harrison. New York, NY: Rolling Stone Press. ISBN 978-0-7432-3581-5.

- Harrison, George (2002) [1980]. I, Me, Mine. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-5900-4.

- Harrison, Olivia (2011). George Harrison: Living in the Material World. New York, NY: Abrams. ISBN 978-1-4197-0220-4.

- Harry, Bill (2003). The George Harrison Encyclopedia. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-0822-0.

- Huntley, Elliot J. (2006). Mystical One: George Harrison – After the Break-up of the Beatles. Toronto, ON: Guernica Editions. ISBN 978-1-55071-197-4.

- Inglis, Ian (2010). The Words and Music of George Harrison. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-313-37532-3.

- Kahn, Ashley (2020). George Harrison on George Harrison: Interviews and Encounters. Chicago, IL: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-64160-051-4.

- Leng, Simon (2006). While My Guitar Gently Weeps: The Music of George Harrison. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard. ISBN 978-1-4234-0609-9.

- MacFarlane, Thomas (2019). The Music of George Harrison. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-59910-9.

- Madinger, Chip; Easter, Mark (2000). Eight Arms to Hold You: The Solo Beatles Compendium. Chesterfield, MO: 44.1 Productions. ISBN 0-615-11724-4.

- Pieper, Jörg (2012). The Solo Beatles Film & TV Chronicle 1971–1980. Stockholm: Premium Förlag. ISBN 978-1-4092-8301-0.

- Rodriguez, Robert (2010). Fab Four FAQ 2.0: The Beatles' Solo Years, 1970–1980. Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4.

- Snow, Mat (2013). The Beatles Solo: The Illustrated Chronicles of John, Paul, George, and Ringo After the Beatles (Volume 3: George). New York, NY: Race Point Publishing. ISBN 978-1-937994-26-6.

- Tillery, Gary (2011). Working Class Mystic: A Spiritual Biography of George Harrison. Wheaton, IL: Quest Books. ISBN 978-0-8356-0900-5.

- Woffinden, Bob (1981). The Beatles Apart. London: Proteus. ISBN 0-906071-89-5.