History of the Americas

The history of the Americas begins with people migrating to these areas from Asia during the height of an ice age. These groups are generally believed to have been isolated from the people of the "Old World" until the coming of Europeans in the 10th century from Iceland led by Leif Erikson, and in 1492 with the voyages of Christopher Columbus.

The ancestors of today's American Indigenous peoples were the Paleo-Indians; they were hunter-gatherers who migrated into North America. The most popular theory asserts that migrants came to the Americas via Beringia, the land mass now covered by the ocean waters of the Bering Strait. Small lithic stage peoples followed megafauna like bison, mammoth (now extinct), and caribou, thus gaining the modern nickname "big-game hunters." Groups of people may also have traveled into North America on shelf or sheet ice along the northern Pacific coast.

Sedentary societies developed primarily in two regions: Mesoamerica and the Andean civilizations. Mesoamerican cultures include Zapotec, Toltec, Olmec, Maya, Aztec, Mixtec, Totonac, Teotihuacan, Huastec people, Purépecha, Izapa and Mazatec.[1] Andean cultures include Inca, Caral-Supe, Wari, Tiwanaku, Chimor, Moche, Muisca, Chavin, Paracas and Nazca.

After the voyages of Christopher Columbus in 1492, Spanish and later Portuguese, English, French and Dutch colonial expeditions arrived in the New World, conquering and settling the discovered lands, which led to a transformation of the cultural and physical landscape in the Americas. Spain colonized most of the Americas from present-day Southwestern United States, Florida and the Caribbean to the southern tip of South America. Portugal settled in what is mostly present-day Brazil while England established colonies on the Eastern coast of the United States, as well as the North Pacific coast and in most of Canada. France settled in Quebec and other parts of Eastern Canada and claimed an area in what is today the central United States. The Netherlands settled New Netherland (administrative centre New Amsterdam – now New York), some Caribbean islands and parts of Northern South America.

European colonization of the Americas led to the rise of new cultures, civilizations and eventually states, which resulted from the fusion of Native American, European, and African traditions, peoples and institutions. The transformation of American cultures through colonization is evident in architecture, religion, gastronomy, the arts and particularly languages, the most widespread being Spanish (376 million speakers), English (348 million) and Portuguese (201 million). The colonial period lasted approximately three centuries, from the early 16th to the early 19th centuries, when Brazil and the larger Hispanic American nations declared independence. The United States obtained independence from Great Britain much earlier, in 1776, while Canada formed a federal dominion in 1867 and received legal independence in 1931. Others remained attached to their European parent state until the end of the 19th century, such as Cuba and Puerto Rico which were linked to Spain until 1898. Smaller territories such as Guyana obtained independence in the mid-20th century, while certain Caribbean islands and French Guiana remain part of a European power to this day.

Pre-colonization

Migration into the continents

The specifics of Paleo-Indian migration to and throughout the Americas, including the exact dates and routes traveled, are subject to ongoing research and discussion.[2] The traditional theory has been that these early migrants moved into the Beringia land bridge between eastern Siberia and present-day Alaska around 40,000 – 17,000 years ago, when sea levels were significantly lowered due to the Quaternary glaciation.[2][3] These people are believed to have followed herds of now-extinct Pleistocene megafauna along ice-free corridors that stretched between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets.[4] Another route proposed is that, either on foot or using primitive boats, they migrated down the Pacific Northwest coast to South America.[5] Evidence of the latter would since have been covered by a sea level rise of a hundred meters following the last ice age.[6]

Archaeologists contend that the Paleo-Indian migration out of Beringia (eastern Alaska), ranges from 40,000 to around 16,500 years ago.[7][8][9] This time range is a hot source of debate. The few agreements achieved to date are the origin from Central Asia, with widespread habitation of the Americas during the end of the last glacial period, or more specifically what is known as the late glacial maximum, around 16,000 – 13,000 years before present.[9][10]

The American Journal of Human Genetics released an article in 2007 stating "Here we show, by using 86 complete mitochondrial genomes, that all Indigenous American haplogroups, including Haplogroup X (mtDNA), were part of a single founding population."[11] Amerindian groups in the Bering Strait region exhibit perhaps the strongest DNA or mitochondrial DNA relations to Siberian peoples. The genetic diversity of Amerindian indigenous groups increase with distance from the assumed entry point into the Americas.[12][13] Certain genetic diversity patterns from West to East suggest, particularly in South America, that migration proceeded first down the west coast, and then proceeded eastward.[14] Geneticists have variously estimated that peoples of Asia and the Americas were part of the same population from 42,000 to 21,000 years ago.[15]

New studies shed light on the founding population of indigenous Americans, suggesting that their ancestry traced to both east Asian and western Eurasians who migrated to North America directly from Siberia. A 2013 study in the journal Nature reported that DNA found in the 24,000-year-old remains of a young boy in Mal’ta Siberia suggest that up to one-third of the indigenous Americans may have ancestry that can be traced back to western Eurasians, who may have "had a more north-easterly distribution 24,000 years ago than commonly thought"[16] Professor Kelly Graf said that "Our findings are significant at two levels. First, it shows that Upper Paleolithic Siberians came from a cosmopolitan population of early modern humans that spread out of Africa to Europe and Central and South Asia. Second, Paleoindian skeletons with phenotypic traits atypical of modern-day Native Americans can be explained as having a direct historical connection to Upper Paleolithic Siberia." A route through Beringia is seen as more likely than the Solutrean hypothesis.[17]

On October 3, 2014, the Oregon cave where the oldest DNA evidence of human habitation in North America was found was added to the National Register of Historic Places. The DNA, radiocarbon dated to 14,300 years ago, was found in fossilized human coprolites uncovered in the Paisley Five Mile Point Caves in south central Oregon.[18]

Lithic stage (before 8000 BCE)

The Lithic stage or Paleo-Indian period, is the earliest classification term referring to the first stage of human habitation in the Americas, covering the Late Pleistocene epoch. The time period derives its name from the appearance of "Lithic flaked" stone tools. Stone tools, particularly projectile points and scrapers, are the primary evidence of the earliest well known human activity in the Americas. Lithic reduction stone tools are used by archaeologists and anthropologists to classify cultural periods.

Archaic stage (8000–1000 BCE)

Several thousand years after the first migrations, the first complex civilizations arose as hunter-gatherers settled into semi-agricultural communities. Identifiable sedentary settlements began to emerge in the so-called Middle Archaic period around 6000 BCE. Particular archaeological cultures can be identified and easily classified throughout the Archaic period.

In the late Archaic, on the north-central coastal region of Peru, a complex civilization arose which has been termed the Norte Chico civilization, also known as Caral-Supe. It is the oldest known civilization in the Americas and one of the six sites where civilization originated independently and indigenously in the ancient world, flourishing between the 30th and 18th centuries BC. It pre-dated the Mesoamerican Olmec civilization by nearly two millennia. It was contemporaneous with the Egypt following the unification of its kingdom under Narmer and the emergence of the first Egyptian hieroglyphics.

Monumental architecture, including earthwork platform mounds and sunken plazas have been identified as part of the civilization. Archaeological evidence points to the use of textile technology and the worship of common god symbols. Government, possibly in the form of theocracy, is assumed to have been required to manage the region. However, numerous questions remain about its organization. In archaeological nomenclature, the culture was pre-ceramic culture of the pre-Columbian Late Archaic period. It appears to have lacked ceramics and art.

Ongoing scholarly debate persists over the extent to which the flourishing of Norte Chico resulted from its abundant maritime food resources, and the relationship that these resources would suggest between coastal and inland sites. The role of seafood in the Norte Chico diet has been a subject of scholarly debate. In 1973, examining the Aspero region of Norte Chico, Michael E. Moseley contended that a maritime subsistence (seafood) economy had been the basis of society and its early flourishing. This theory, later termed "maritime foundation of Andean Civilization" was at odds with the general scholarly consensus that civilization arose as a result of intensive grain-based agriculture, as had been the case in the emergence of civilizations in northeast Africa (Egypt) and southwest Asia (Mesopotamia).

While earlier research pointed to edible domestic plants such as squash, beans, lucuma, guava, pacay, and camote at Caral, publications by Haas and colleagues have added avocado, achira, and maize (Zea Mays) to the list of foods consumed in the region. In 2013, Haas and colleagues reported that maize was a primary component of the diet throughout the period of 3000 to 1800 BC.[19] Cotton was another widespread crop in Norte Chico, essential to the production of fishing nets and textiles. Jonathan Haas noted a mutual dependency, whereby "The prehistoric residents of the Norte Chico needed the fish resources for their protein and the fishermen needed the cotton to make the nets to catch the fish."

In the 2005 book 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, journalist Charles C. Mann surveyed the literature at the time, reporting a date "sometime before 3200 BC, and possibly before 3500 BC" as the beginning date for the formation of Norte Chico. He notes that the earliest date securely associated with a city is 3500 BC, at Huaricanga in the (inland) Fortaleza area. The Norte Chico civilization began to decline around 1800 BC as more powerful centers appeared to the south and north along its coast, and to the east within the Andes Mountains.

Mesoamerica, the Woodland Period, and Mississippian culture (2000 BCE – 500 CE)

After the decline of the Norte Chico civilization, numerous complex civilizations and centralized polities developed in the Western Hemisphere: The Chavin, Nazca, Moche, Huari, Quitus, Cañaris, Chimu, Pachacamac, Tiahuanaco, Aymara and Inca in the Andes; the Muisca, Tairona, Miskito, Huetar, and Talamanca in the Intermediate Area; the Taínos in the Caribbean; and the Olmecs, Maya, Toltecs, Mixtecs, Zapotecs, Aztecs, Purepecha and Nicoya in Mesoamerica.

The Olmec civilization was the first Mesoamerican civilization, beginning around 1600–1400 BC and ending around 400 BC. Mesoamerica is considered one of the six sites around the globe in which civilization developed independently and indigenously. This civilization is considered the mother culture of the Mesoamerican civilizations. The Mesoamerican calendar, numeral system, writing, and much of the Mesoamerican pantheon seem to have begun with the Olmec.

Some elements of agriculture seem to have been practiced in Mesoamerica quite early. The domestication of maize is thought to have begun around 7,500 to 12,000 years ago. The earliest record of lowland maize cultivation dates to around 5100 BC.[20] Agriculture continued to be mixed with a hunting-gathering-fishing lifestyle until quite late compared to other regions, but by 2700 BC, Mesoamericans were relying on maize, and living mostly in villages. Temple mounds and classes started to appear. By 1300/ 1200 BC, small centres coalesced into the Olmec civilization, which seems to have been a set of city-states, united in religious and commercial concerns. The Olmec cities had ceremonial complexes with earth/clay pyramids, palaces, stone monuments, aqueducts and walled plazas. The first of these centers was at San Lorenzo (until 900 bc). La Venta was the last great Olmec centre. Olmec artisans sculpted jade and clay figurines of Jaguars and humans. Their iconic giant heads – believed to be of Olmec rulers – stood in every major city.

The Olmec civilization ended in 400 BC, with the defacing and destruction of San Lorenzo and La Venta, two of the major cities. It nevertheless spawned many other states, most notably the Mayan civilization, whose first cities began appearing around 700–600 BC. Olmec influences continued to appear in many later Mesoamerican civilizations.

Cities of the Aztecs, Mayas, and Incas were as large and organized as the largest in the Old World, with an estimated population of 200,000 to 350,000 in Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec Empire. The market established in the city was said to have been the largest ever seen by the conquistadors when they arrived. The capital of the Cahokians, Cahokia, located near modern East St. Louis, Illinois, may have reached a population of over 20,000. At its peak, between the 12th and 13th centuries, Cahokia may have been the most populous city in North America. Monk's Mound, the major ceremonial center of Cahokia, remains the largest earthen construction of the prehistoric New World.

These civilizations developed agriculture as well, breeding maize (corn) from having ears 2–5 cm in length to perhaps 10–15 cm in length. Potatoes, tomatoes, beans (greens), pumpkins, avocados, and chocolate are now the most popular of the pre-Columbian agricultural products. The civilizations did not develop extensive livestock as there were few suitable species, although alpacas and llamas were domesticated for use as beasts of burden and sources of wool and meat in the Andes. By the 15th century, maize was being farmed in the Mississippi River Valley after introduction from Mexico. The course of further agricultural development was greatly altered by the arrival of Europeans.

Classic stage (800 BCE – 1533 CE)

Cahokia

Cahokia was a major regional chiefdom, with trade and tributary chiefdoms located in a range of areas from bordering the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico.

- Haudenosaune

The Iroquois League of Nations or "People of the Long House", based in present-day upstate and western New York, had a confederacy model from the mid-15th century. It has been suggested that their culture contributed to political thinking during the development of the later United States government. Their system of affiliation was a kind of federation, different from the strong, centralized European monarchies.[21][22][23]

Leadership was restricted to a group of 50 sachem chiefs, each representing one clan within a tribe; the Oneida and Mohawk people had nine seats each; the Onondagas held fourteen; the Cayuga had ten seats; and the Seneca had eight. Representation was not based on population numbers, as the Seneca tribe greatly outnumbered the others. When a sachem chief died, his successor was chosen by the senior woman of his tribe in consultation with other female members of the clan; property and hereditary leadership were passed matrilineally. Decisions were not made through voting but through consensus decision making, with each sachem chief holding theoretical veto power. The Onondaga were the "firekeepers", responsible for raising topics to be discussed. They occupied one side of a three-sided fire (the Mohawk and Seneca sat on one side of the fire, the Oneida and Cayuga sat on the third side.)[23]

Long-distance trading did not prevent warfare and displacement among the indigenous peoples, and their oral histories tell of numerous migrations to the historic territories where Europeans encountered them. The Iroquois invaded and attacked tribes in the Ohio River area of present-day Kentucky and claimed the hunting grounds. Historians have placed these events as occurring as early as the 13th century, or in the 17th century Beaver Wars.[24]

Through warfare, the Iroquois drove several tribes to migrate west to what became known as their historically traditional lands west of the Mississippi River. Tribes originating in the Ohio Valley who moved west included the Osage, Kaw, Ponca and Omaha people. By the mid-17th century, they had resettled in their historical lands in present-day Kansas, Nebraska, Arkansas and Oklahoma. The Osage warred with Caddo-speaking Native Americans, displacing them in turn by the mid-18th century and dominating their new historical territories.[24]

Oasisamerica

- Pueblo people

The Great Kiva of Chetro Ketl at the Chaco Culture National Historical Park, UNESCO World Heritage Site

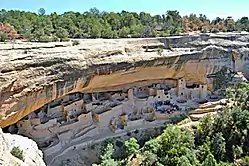

The Great Kiva of Chetro Ketl at the Chaco Culture National Historical Park, UNESCO World Heritage Site Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site

Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site Taos Pueblo, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is an Ancient Pueblo belonging to a Native American tribe of Pueblo people, marking the cultural development in the region during the Pre-Columbian era.

Taos Pueblo, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is an Ancient Pueblo belonging to a Native American tribe of Pueblo people, marking the cultural development in the region during the Pre-Columbian era. White House Ruins, Canyon de Chelly National Monument

White House Ruins, Canyon de Chelly National Monument

The Pueblo people of what is now occupied by the Southwestern United States and northern Mexico, living conditions were that of large stone apartment like adobe structures. They live in Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, and possibly surrounding areas.

Aridoamerica

- Chichimeca

Chichimeca was the name that the Mexica (Aztecs) generically applied to a wide range of semi-nomadic peoples who inhabited the north of modern-day Mexico, and carried the same sense as the European term "barbarian". The name was adopted with a pejorative tone by the Spaniards when referring especially to the semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer peoples of northern Mexico.

Mesoamerica

- Olmec

The Olmec civilization emerged around 1200 BCE in Mesoamerica and ended around 400 BCE. Olmec art and concepts influenced surrounding cultures after their downfall. This civilization was thought to be the first in America to develop a writing system. After the Olmecs abandoned their cities for unknown reasons, the Maya, Zapotec and Teotihuacan arose.

- Purepecha

The Purepecha civilization emerged around 1000 CE in Mesoamerica. They flourished from 1100 CE to 1530 CE. They continue to live on in the state of Michoacán. Fierce warriors, they were never conquered and in their glory years, successfully sealed off huge areas from Aztec domination.

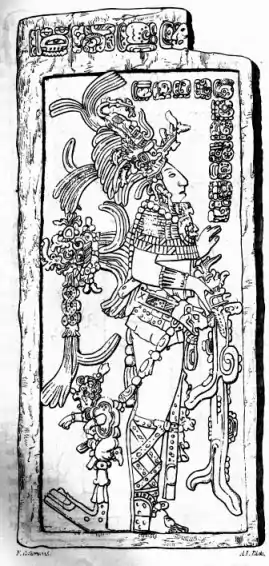

- Maya

Maya history spans 3,000 years. The Classic Maya may have collapsed due to changing climate in the end of the 10th century.

- Toltec

The Toltec were a nomadic people, dating from the 10th–12th century, whose language was also spoken by the Aztecs.

- Teotihuacan

Teotihuacan (4th century BCE – 7/8th century CE) was both a city, and an empire of the same name, which, at its zenith between 150 and the 5th century, covered most of Mesoamerica.

- Aztec

The Aztec having started to build their empire around 14th century found their civilization abruptly ended by the Spanish conquistadors. They lived in Mesoamerica, and surrounding lands. Their capital city Tenochtitlan was one of the largest cities of all time.

South America

- Norte Chico

The oldest known civilization of the Americas was established in the Norte Chico region of modern Peru. Complex society emerged in the group of coastal valleys, between 3000 and 1800 BCE. The Quipu, a distinctive recording device among Andean civilizations, apparently dates from the era of Norte Chico's prominence.

- Chavín

The Chavín established a trade network and developed agriculture by as early as (or late compared to the Old World) 900 BCE according to some estimates and archaeological finds. Artifacts were found at a site called Chavín in modern Peru at an elevation of 3,177 meters. Chavín civilization spanned from 900 BCE to 300 BCE.

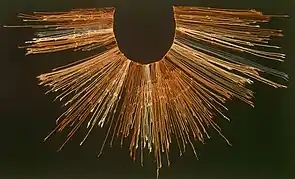

- Inca

Holding their capital at the great city of Cusco, the Inca civilization dominated the Andes region from 1438 to 1533. Known as Tawantinsuyu, or "the land of the four regions", in Quechua, the Inca culture was highly distinct and developed. Cities were built with precise, unmatched stonework, constructed over many levels of mountain terrain. Terrace farming was a useful form of agriculture. There is evidence of excellent metalwork and even successful trepanation of the skull in Inca civilization.

European colonization

_Nova_reperta_(Speculum_diuersarum_imaginum_speculatiuarum_1638).tif.png.webp)

Around 1000, the Vikings established a short-lived settlement in Newfoundland, now known as L'Anse aux Meadows. Speculations exist about other Old World discoveries of the New World, but none of these are generally or completely accepted by most scholars.

Spain sponsored a major exploration led by Italian explorer Christopher Columbus in 1492; it quickly led to extensive European colonization of the Americas. The Europeans brought Old World diseases which are thought to have caused catastrophic epidemics and a huge decrease of the native population. Columbus came at a time in which many technical developments in sailing techniques and communication made it possible to report his voyages easily and to spread word of them throughout Europe. It was also a time of growing religious, imperial and economic rivalries that led to a competition for the establishment of colonies.

Colonial period

15th to 19th century colonies in the New World:

- Spanish colonization of the Americas (1492)

- Viceroyalty of New Spain (1535–1821)

- Viceroyalty of Peru (1542–1824)

- Spanish Main

- Spanish West Indies

- Captaincy General of Guatemala

- British America / Thirteen Colonies (1584/1607 – 1776/20th century)

- French Saint-Domingue (1659–1804)

- Danish West Indies

- New Netherland

- New France

- Captaincy General of Venezuela

- Portuguese colonization of the Americas (1499–1822)

- Colonial Brazil (1500–1815)

Decolonization

The formation of sovereign states in the New World began with the United States Declaration of Independence of 1776. The American Revolutionary War lasted through the period of the Siege of Yorktown—its last major campaign—in the early autumn of 1781, with peace being achieved in 1783. In 1804, after the French of Napoleon Bonaparte were defeated during the Haitian Revolution under the black leadership of Jean-Jacques Dessalines declare the colony of Saint-Domingue independence of the Haitian Declaration of Independence as he renamed the country Ayiti meaning (Land of Mountains), Haiti became the world's first black-led republic in the New World, the first Caribbean state as well as the first Latin American country and the second oldest independent nation in the Western Hemisphere after the United States to win independence from Britain in 1783.

The Spanish colonies won their independence in the first quarter of the 19th century, in the Spanish American wars of independence. Simón Bolívar and José de San Martín, among others, led their independence struggle. Although Bolivar attempted to keep the Spanish-speaking parts of Latin America politically allied, they rapidly became independent of one another as well, and several further wars were fought, such as the Paraguayan War and the War of the Pacific. (See Latin American integration.) In the Portuguese colony Dom Pedro I (also Pedro IV of Portugal), son of the Portuguese king Dom João VI, proclaimed the country's independence in 1822 and became Brazil's first Emperor. This was peacefully accepted by the crown in Portugal, upon compensation.

Effects of slavery

Slavery has had a significant role in the economic development of the New World after the colonization of the Americas by the Europeans. The cotton, tobacco, and sugar cane harvested by slaves became important exports for the United States and the Caribbean countries.

20th century

North America

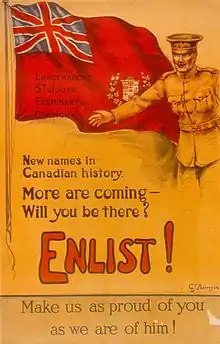

As a part of the British Empire, Canada immediately entered World War I when it broke out in 1914. Canada bore the brunt of several major battles during the early stages of the war, including the use of poison gas attacks at Ypres. Losses became grave, and the government eventually brought in conscription, despite the fact this was against the wishes of the majority of French Canadians. In the ensuing Conscription Crisis of 1917, riots broke out on the streets of Montreal. In neighboring Newfoundland, the new dominion suffered a devastating loss on July 1, 1916, the First day on the Somme.

The United States stayed out of the conflict until 1917, when it joined the Entente powers. The United States was then able to play a crucial role at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 that shaped interwar Europe. Mexico was not part of the war, as the country was embroiled in the Mexican Revolution at the time.

The 1920s brought an age of great prosperity in the United States, and to a lesser degree Canada. But the Wall Street Crash of 1929 combined with drought ushered in a period of economic hardship in the United States and Canada. From 1936 to 1949, there was a popular uprising against the anti-Catholic Mexican government of the time, set off specifically by the anti-clerical provisions of the Mexican Constitution of 1917.

Once again, Canada found itself at war before its neighbors, with numerically modest but significant contributions overseas such as the Battle of Hong Kong and the Battle of Britain. The entry of the United States into the war helped to tip the balance in favour of the allies. Two Mexican tankers, transporting oil to the United States, were attacked and sunk by the Germans in the Gulf of Mexico waters, in 1942. The incident happened in spite of Mexico's neutrality at that time. This led Mexico to enter the conflict with a declaration of war on the Axis nations. The destruction of Europe wrought by the war vaulted all North American countries to more important roles in world affairs, especially the United States, which emerged as a "superpower".

The early Cold War era saw the United States as the most powerful nation in a Western coalition of which Mexico and Canada were also a part. In Canada, Quebec was transformed by the Quiet Revolution and the emergence of Quebec nationalism. Mexico experienced an era of huge economic growth after World War II, a heavy industrialization process and a growth of its middle class, a period known in Mexican history as "El Milagro Mexicano" (the Mexican miracle). The Caribbean saw the beginnings of decolonization, while on the largest island the Cuban Revolution introduced Cold War rivalries into Latin America.

The civil rights movement in the U.S. ended Jim Crow and empowered black voters in the 1960s, which allowed black citizens to move into high government offices for the first time since Reconstruction. However, the dominant New Deal coalition collapsed in the mid 1960s in disputes over race and the Vietnam War, and the conservative movement began its rise to power, as the once dominant liberalism weakened and collapsed. Canada during this era was dominated by the leadership of Pierre Elliot Trudeau. In 1982, at the end of his tenure, Canada enshrined a new constitution.

Canada's Brian Mulroney not only ran on a similar platform but also favored closer trade ties with the United States. This led to the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement in January 1989. Mexican presidents Miguel de la Madrid, in the early 1980s and Carlos Salinas de Gortari in the late 1980s, started implementing liberal economic strategies that were seen as a good move. However, Mexico experienced a strong economic recession in 1982 and the Mexican peso suffered a devaluation. In the United States president Ronald Reagan attempted to move the United States back towards a hard anti-communist line in foreign affairs, in what his supporters saw as an attempt to assert moral leadership (compared to the Soviet Union) in the world community. Domestically, Reagan attempted to bring in a package of privatization and regulation to stimulate the economy.

The end of the Cold War and the beginning of the era of sustained economic expansion coincided during the 1990s. On January 1, 1994, Canada, Mexico and the United States signed the North American Free Trade Agreement, creating the world's largest free trade area. In 2000, Vicente Fox became the first non-PRI candidate to win the Mexican presidency in over 70 years. The optimism of the 1990s was shattered by the 9/11 attacks of 2001 on the United States, which prompted military intervention in Afghanistan, which also involved Canada. Canada did not support the United States' later move to invade Iraq, however.

In the U.S. the Reagan Era of conservative national policies, deregulation and tax cuts took control with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. By 2010, political scientists were debating whether the election of Barack Obama in 2008 represented an end of the Reagan Era, or was only a reaction against the bubble economy of the 2000s (decade), which burst in 2008 and became the Late-2000s recession with prolonged unemployment.

| Country or Territory with flag |

Area (km²)[25] (sq mi) |

Population (July 2009 est.)[25] |

Population density per km² (per sq mi) |

Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54 km2 (21 sq mi) | 63,913 | 1,338/km² (37/sq mi) | Hamilton | |

| 9,984,670 km2 (3,855,100 sq mi) | 39,858,480 | 4.2/km² (37/sq mi) | Ottawa | |

| 2,166,086 km2 (836,330 sq mi) | 56,583 | 0.028/km² (21.8/sq mi) | Nuuk | |

| 1,972,550 km2 (761,610 sq mi) | 129,875,529 | 61/km² (0.7/sq mi) | Mexico City | |

| 3,796,742 km2 (1,465,930 sq mi) | 333,287,557 | 87/km² (57/sq mi) | Washington, D.C. | |

| Total | 24,709,000 km2 (9,540,000 sq mi) | 592,296,233 | 25.7/km² (66.4/sq mi) |

Central America

Despite the failure of a lasting political union, the concept of Central American reunification, though lacking enthusiasm from the leaders of the individual countries, rises from time to time. In 1856–1857 the region successfully established a military coalition to repel an invasion by United States adventurer William Walker. Today, all five nations fly flags that retain the old federal motif of two outer blue bands bounding an inner white stripe. (Costa Rica, traditionally the least committed of the five to regional integration, modified its flag significantly in 1848 by darkening the blue and adding a double-wide inner red band, in honor of the French tricolor).

In 1907, a Central American Court of Justice was created. On December 13, 1960, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua established the Central American Common Market ("CACM"). Costa Rica, because of its relative economic prosperity and political stability, chose not to participate in the CACM. The goals for the CACM were to create greater political unification and success of import substitution industrialization policies. The project was an immediate economic success, but was abandoned after the 1969 "Football War" between El Salvador and Honduras. A Central American Parliament has operated, as a purely advisory body, since 1991. Costa Rica has repeatedly declined invitations to join the regional parliament, which seats deputies from the four other former members of the Union, as well as from Panama and the Dominican Republic.

| Country or Territory with flag |

Area (km²)[25] (sq mi) |

Population (July 2009 est.)[25] |

Population density per km² (per sq mi) |

Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22,970 km2 (8,870 sq mi) | 441,471 | 17.79/km² (37/sq mi) | Belmopan | |

| 51,100 km2 (19,700 sq mi) | 5,044,197 | 84.9/km² (21.8/sq mi) | San José | |

| 21,041 km2 (8,124 sq mi) | 6,602,370 | 324.4/km² (0.7/sq mi) | San Salvador | |

| 108,889 km2 (42,042 sq mi) | 17,980,803 | 129/km² (57/sq mi) | Guatemala City | |

| 112,492 km2 (43,433 sq mi) | 9,571,352 | 85/km² (57/sq mi) | Tegucigalpa | |

| 130,375 km2 (50,338 sq mi) | 6,359,689 | 51/km² (103.6/sq mi) | Managua | |

| 75,417 km2 (29,119 sq mi) | 4,337,768 | 56/km² (139.3/sq mi) | Panama City | |

| Total | 560,988 km2 (216,599 sq mi) | 50,807,776 | 74/km² (191/sq mi) |

South America

In the 1960s and 1970s, the governments of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay were overthrown or displaced by U.S.-aligned military dictatorships. These dictatorships detained tens of thousands of political prisoners, many of whom were tortured and/or killed (on inter-state collaboration, see Operation Condor). Economically, they began a transition to neoliberal economic policies. They placed their own actions within the United States Cold War doctrine of "National Security" against internal subversion. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Peru suffered from an internal conflict (see Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement and Shining Path). Revolutionary movements and right-wing military dictatorships have been common, but starting in the 1980s a wave of democratization came through the continent, and democratic rule is widespread now. Allegations of corruption remain common, and several nations have seen crises which have forced the resignation of their presidents, although normal civilian succession has continued.

International indebtedness became a notable problem, as most recently illustrated by Argentina's default in the early 21st century. In recent years, South American governments have drifted to the left, with socialist leaders being elected in Chile, Bolivia, Brazil, Venezuela, and a leftist president in Argentina and Uruguay. Despite the move to the left, South America is still largely capitalist. With the founding of the Union of South American Nations, South America has started down the road of economic integration, with plans for political integration in the European Union style.

| Country or Territory with flag |

Area (km²)[25] (sq mi) |

Population (July 2009 est.)[25] |

Population density per km² (per sq mi) |

Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,766,890 km2 (1,068,300 sq mi) | 40,482,000 | 14.3/km² (37/sq mi) | Buenos Aires | |

| 1,098,580 km2 (424,160 sq mi) | 9,863,000 | 8.4/km² (21.8/sq mi) | La Paz[26] | |

| 8,514,877 km2 (3,287,612 sq mi) | 191,241,714 | 22.0/km² (57/sq mi) | Brasília | |

| 756,950 km2 (292,260 sq mi) | 16,928,873 | 22/km² (57/sq mi) | Santiago | |

| 1,138,910 km2 (439,740 sq mi) | 45,928,970 | 40/km² (103.6/sq mi) | Bogotá | |

| 283,560 km2 (109,480 sq mi) | 14,573,101 | 53.8/km² (139.3/sq mi) | Quito | |

| 12,173 km2 (4,700 sq mi) | 3,140[29] | 0.26/km² (0.7/sq mi) | Stanley | |

| 91,000 km2 (35,000 sq mi) | 221,500[30] | 2.7/km² (5.4/sq mi) | Cayenne | |

| 214,999 km2 (83,012 sq mi) | 772,298 | 3.5/km² (9.1/sq mi) | Georgetown | |

| 406,750 km2 (157,050 sq mi) | 6,831,306 | 15.6/km² (40.4/sq mi) | Asunción | |

| 1,285,220 km2 (496,230 sq mi) | 29,132,013 | 22/km² (57/sq mi) | Lima | |

South Sandwich Islands (United Kingdom)[31] |

3,093 km2 (1,194 sq mi) | 20 | 0/km² (0/sq mi) | Grytviken |

| 163,270 km2 (63,040 sq mi) | 472,000 | 3/km² (7.8/sq mi) | Paramaribo | |

| 176,220 km2 (68,040 sq mi) | 3,477,780 | 19.4/km² (50.2/sq mi) | Montevideo | |

| 916,445 km2 (353,841 sq mi) | 26,814,843 | 30.2/km² (72/sq mi) | Caracas | |

| Total | 17,824,513 km2 (6,882,083 sq mi) | 385,742,554 | 21.5/km² (55.7/sq mi) |

See also

Notes

- "Mesoamerican civilization | History, Olmec, & Maya | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- "Atlas of the Human Journey-The Genographic Project". National Geographic Society. 1996–2008. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- Fitzhugh, Drs. William; Goddard, Ives; Ousley, Steve; Owsley, Doug; Stanford., Dennis. "Paleoamerican". Smithsonian Institution Anthropology Outreach Office. Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- "The peopling of the Americas: Genetic ancestry influences health". Scientific American. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- Fladmark, K. R. (1979). "Alternate Migration Corridors for Early Man in North America". American Antiquity. 44 (1): 55–69. doi:10.2307/279189. JSTOR 279189. S2CID 162243347.

- "68 Responses to "Sea will rise 'to levels of last Ice Age'"". Center for Climate Systems Research, Columbia University. 26 January 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- "Introduction". Government of Canada. Parks Canada. 2009. Archived from the original on 24 April 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2010.

Canada's oldest known home is a cave in Yukon occupied not 12,000 years ago like the U.S. sites, but at least 20,000 years ago

- "Pleistocene Archaeology of the Old Crow Flats". Vuntut National Park of Canada. 2008. Archived from the original on 22 October 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

However, despite the lack of this conclusive and widespread evidence, there are suggestions of human occupation in the northern Yukon about 24,000 years ago, and hints of the presence of humans in the Old Crow Basin as far back as about 40,000 years ago.

- "Journey of mankind". Brad Shaw Foundation. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- Bonatto, SL; Salzano, FM (1997). "A single and early migration for the peopling of the Americas supported by mitochondrial DNA sequence data". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (5): 1866–71. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.1866B. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.5.1866. PMC 20009. PMID 9050871.

- "First Americans". Southern Methodist University-David J. Meltzer, B.A., M.A., Ph. D. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- "The peopling of the Americas: Genetic ancestry influences health". Scientific American. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- "First Americans Endured 20,000-Year Layover - Jennifer Viegas, Discovery News". Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- Wang, Sijia; Lewis, Cecil M.; Jakobsson, Mattias; Ramachandran, Sohini; Ray, Nicolas; Bedoya, Gabriel; Rojas, Winston; Parra, Maria V.; Molina, Julio A.; Gallo, Carla; Mazzotti, Guido; Poletti, Giovanni; Hill, Kim; Hurtado, Ana M.; Labuda, Damian; Klitz, William; Barrantes, Ramiro; Bortolini, Maria Cátira; Salzano, Francisco M.; Petzl-Erler, Maria Luiza; Tsuneto, Luiza T.; Llop, Elena; Rothhammer, Francisco; Excoffier, Laurent; Feldman, Marcus W.; Rosenberg, Noah A.; Ruiz-Linares, Andrés (2007). "Genetic Variation and Population Structure in Native Americans". PLOS Genetics. 3 (11): 3(11). doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030185. PMC 2082466. PMID 18039031.

- Fagundes, Nelson J.R.; Ricardo Kanitz; Roberta Eckert; Ana C.S. Valls; Mauricio R. Bogo; Francisco M. Salzano; David Glenn Smith; Wilson A. Silva; Marco A. Zago; Andrea K. Ribeiro-dos-Santos; Sidney E.B. Santos; Maria Luiza Petzl-Erler; Sandro L. Bonatto (2008). "Mitochondrial Population Genomics Supports a Single Pre-Clovis Origin with a Coastal Route for the Peopling of the Americas" (PDF). American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (3): 583–592. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.11.013. PMC 2427228. PMID 18313026. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- Maanasa Raghavan; Pontus Skoglund; Kelly E. Graf; Mait Metspalu; Anders Albrechtsen; Ida Moltke; Simon Rasmussen; Thomas W. Stafford Jr; Ludovic Orlando; Ene Metspalu; Monika Karmin; Kristiina Tambets; Siiri Rootsi; Reedik Mägi; Paula F. Campos; Elena Balanovska; Oleg Balanovsky; Elza Khusnutdinova; Sergey Litvinov; Ludmila P. Osipova; Sardana A. Fedorova; Mikhail I. Voevoda; Michael DeGiorgio; Thomas Sicheritz-Ponten; Søren Brunak; Svetlana Demeshchenko; Toomas Kivisild; Richard Villems; Rasmus Nielsen; Mattias Jakobsson; Eske Willerslev (2013). "Upper Palaeolithic Siberian genome reveals dual ancestry of Native Americans". Nature. 505 (7481): 87–91. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...87R. doi:10.1038/nature12736. PMC 4105016. PMID 24256729.

- "Ancient Siberian genome reveals genetic origins of Native Americans". PHYSORG. 20 November 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- Staff (3 October 2014). "Cave containing earliest human DNA dubbed historic". Phys.org. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- Haas, Jonathan; Winifred Creamer; Luis Huamán Mesía; David Goldstein; Karl Reinhard; Cindy Vergel Rodríguez (2013). "Evidence for maize (Zea mays) in the Late Archaic (3000–1800 B.C.) in the Norte Chico region of Peru". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (13): 4945–4949. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.4945H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1219425110. PMC 3612639. PMID 23440194.

New data drawn from coprolites, pollen records, and stone tool residues, combined with 126 radiocarbon dates, demonstrate that maize was widely grown, intensively processed, and constituted a primary component of the diet throughout the period from 3000 to 1800 B.C.

- "Agriculture's origin may be hidden in 'invisible' clues". Scienceblog.com. 14 February 2003. Retrieved 18 April 2009.

- Woods, Thomas E (2007). 33 questions about American history you're not supposed to ask. Crown Forum. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-307-34668-1.

- Wright, R (2005). Stolen Continents: 500 Years of Conquest and Resistance in the Americas. Mariner Books. ISBN 978-0-618-49240-4.

- Tooker E (1990). "The United States Constitution and the Iroquois League". In Clifton JA (ed.). The Invented Indian: Cultural Fictions and Government Policies. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. pp. 107–128. ISBN 978-1-56000-745-6.

- Burns, LF. "Osage". Oklahoma Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- Land areas and population estimates are taken from The 2008 World Factbook which currently uses July 2007 data, unless otherwise noted.

- La Paz is the administrative capital of Bolivia;

- Includes Easter Island in the Pacific Ocean, a Chilean territory frequently reckoned in Oceania. Santiago is the administrative capital of Chile; Valparaíso is the site of legislative meetings.

- Claimed by Argentina.

- Falkland Islands: July 2008 population estimate. CIA World Factbook.

- (January 2009) INSEE, Government of France. "Population des régions au 1er janvier" (in French). Retrieved 20 January 2009.

- Claimed by Argentina; the South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in the South Atlantic Ocean are commonly associated with Antarctica (due to proximity) and have no permanent population, only hosting a periodic contingent of about 100 researchers and visitors.

Further reading

- Boyer, Paul S. The Oxford Companion to United States History (2001) excerpt and text search; online at many libraries

- Carnes, Mark C., and John A. Garraty. The American Nation: A History of the United States: AP Edition (2008)

- Egerton, Douglas R. et al. The Atlantic World: A History, 1400–1888 (2007), college textbook; 530pp

- Elliott, John H. Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492–1830 (2007), 608pp excerpt and text search, advanced synthesis

- Hardwick, Susan W., Fred M. Shelley, and Donald G. Holtgrieve. The Geography of North America: Environment, Political Economy, and Culture (2007)

- Jacobs, Heidi Hayes, and Michal L. LeVasseur. World Studies: Latin America: Geography – History – Culture (2007)

- Bruce E. Johansen, The Native Peoples of North America: A History (2006)

- Kaltmeier, Olaf, Josef Raab, Michael Stewart Foley, Alice Nash, Stefan Rinke, and Mario Rufer. The Routledge Handbook to the History and Society of the Americas. New York: Routledge (2019)

- Keen, Benjamin, and Keith Haynes. A History of Latin America (2008)

- Kennedy, David M., Lizabeth Cohen, and Thomas Bailey. The American Pageant (2 vol 2008), U.S. history

- The Canadian Encyclopedia

- Morton, Desmond. A Short History of Canada 5th ed (2001)

- Veblen, Thomas T. Kenneth R. Young, and Antony R. Orme. The Physical Geography of South America (2007)

.svg.png.webp)