Rosa canina

Rosa canina, commonly known as the dog rose,[1] is a variable climbing, wild rose species native to Europe, northwest Africa, and western Asia.

| Rosa canina | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Rosaceae |

| Genus: | Rosa |

| Species: | R. canina |

| Binomial name | |

| Rosa canina | |

| Synonyms | |

|

See text | |

Description

The dog rose is a deciduous shrub normally ranging in height from 1–5 metres (3.3–16.4 ft), though sometimes it can scramble higher into the crowns of taller trees. Its multiple arching stems,[2] are covered with small, sharp, hooked prickles, which aid it in climbing. The leaves are pinnate, with 5–7 leaflets,[3] and have a delicious fragrance when bruised.[4]

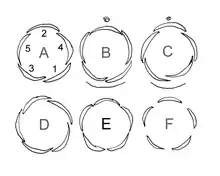

The dog rose blooms from June to July, with sweet-scented flowers that are usually pale pink, but can vary between a deep pink and white. They are 4–6 centimetres (1.6–2.4 in) in diameter with five petals. Like other roses it has a quintuscial aestivation (see sketch A in diagram). Unusually though, of its five sepals, when viewed from underneath, two are whiskered (or “bearded”) on both sides, two are quite smooth and one is whiskered on one side only.[5]: 182 It has usually 10 or more pistils, and multiple stamens.[2]

Flowers mature in September to October,[2] into an oval, 1.5–2-centimetre (0.59–0.79 in), red-orange hips.[6] The fruits can persist on the plant for several months (if not eaten by wildlife) and become black.[2][7]

It's form and flowers can be confused with fieldbriar Rosa agrestis and sweetbriar Rosa rubiginosa.

Classification

Classical writers did not recognise Rosa canina as a rose, but called it Cynorrhodon, from the Greek "kunórodon". In 1538, Turner called it "Cynosbatos : wild hep or brere tree". Yet in 1551, Matthias de l'Obel classified it as a rose, under the name, "Canina Rosa odorata et silvestris", in his herbal "Rubus canis: Brere bush or hep tree" .[8]

Based on a 2013 DNA analysis using amplified fragment length polymorphisms of wild-rose samples from a transect across Europe (900 samples from section Caninae, and 200 from other sections), it has been suggested that the following named species are best considered as belonging to a single Rosa canina species complex:[9]

- R. balsamica Besser

- R. caesia Sm.

- R. corymbifera Borkh.

- R. dumalis Bechst.

- R. montana Chaix

- R. stylosa Desv.

- R. subcanina (Christ) Vuk.

- R. subcollina (Christ) Vuk.

- R. × irregularis Déségl. & Guillon

Numerous cultivars have been named, though few are common in cultivation. The cultivar Rosa canina 'Assisiensis' is the only dog rose without thorns. Thought to be linked to Saint Francis of Assisi, hence the name.[10]

Cultivation

The dog rose is hardy to zone 3 in the UK (USDA hardiness zone 3-7), tolerates maritime exposure, grows well in a sunny position, and grows even in heavy clay soils, but like all roses dislikes water-logged soils or very dry sites. In deep shade, it usually fails to flower and fruit.[11]

Name and etymology

The botanical name is derived from the common names 'dog rose' or similar in several European languages, including classical Latin and ancient (Hellenistic period) Greek. The Roman naturalist Pliny attributed the name dog rose to a belief that the plant's root could cure the bite of a mad dog. It is not clear if the dogs were rabid.[12] According to The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable,[13] the English name is a direct translation of the plant's name from classical Latin, rosa canina, itself a translation of the Greek κυνόροδον ('kunórodon'); It is known to have been used to treat the bite of rabid dogs in the 18th and 19th centuries.[14] The origin of its name may be related to the hooked prickles on the plant that have resemblance to a dog's canines.[15] It is sometimes considered that the word 'dog' has a disparaging meaning in this context, indicating 'worthless' as compared with cultivated garden roses.[16]

Pests and diseases

.jpg.webp)

The dog rose can be attacked by aphids, leafhoppers, glasshouse red spider mite, scale insects, caterpillars, rose leaf-rolling sawfly, and leaf-cutting bees.[11]

When a gall wasp lays eggs into a leaf axillary or terminal bud the plant develops a chemically induced distortion known as rose gall (see photo).[2]

Buds and leaves may be eaten by rabbits and deer, despite the thorns.[11]

It may be affected by rose rust (see photo) and powdery mildews (Sphaerotheca pannosa var. rosae),[1] and downy mildew (Peronospora sparsa).[2]

It is notably susceptible to honey fungus.[17]

Cultivation and uses

Rose hip essential oil is composed mainly of alcohols, monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes.[18]

The fruit is used to make syrup, tea, and preserves (jam and marmalade), and is used in the making of pies, stews, and wine. The flowers can be made into a syrup, eaten in salads, candied, or preserved in vinegar, honey or brandy.[19] During World War II in the United States, Rosa canina was planted in victory gardens; it can still be found growing throughout that country, including on roadsides, in pastures and nature conservation areas.[2]

In Poland, the petals are used to make a jam that is particularly suitable for filling doughnuts.[20][21]

In Bulgaria, where the dog rose grows in abundance, its hips are used to make sweet wine and tea.[22]

Genetics

Dog roses have an unusual kind of meiosis which is sometimes called permanent odd polyploidy, although it can also occur with even polyploidy (e.g. in tetraploids or hexaploids). Regardless of ploidy level, only seven bivalents are formed leaving the other chromosomes as univalents. Univalents are included in egg cells, but not in pollen.[23][24] Similar processes occur in some other organisms.[25] Dog roses are most commonly pentaploid, i.e. five times the base number of seven chromosomes for the genus Rosa, but may be tetraploid or hexaploid as well.

Invasive species

Dog rose is an invasive species in the high country of New Zealand. It was recognised as displacing native vegetation as early as 1895[26] although the Department of Conservation does not consider it to be a conservation threat.[27]

The dog rose is a declared weed in Australia under the Natural Resources Management Act, 2004 as the plant out-competes native vegetation, provides shelter to pests such as foxes and rabbits, is unpalatable to stock, large shrubs are resistant to grazing, therefore do not get eaten by farm animals. The dog rose invades native bushland therefore reducing biodiversity and the presence of desirable pasture species.[28] It is a biosecurity risk as it hosts fruit fly.[29]

In the USA, it is classed as a weed and invasive in some regions or habitats, where it may displace desirable vegetation due to its large size and ability of regeneration from sprouts. It can also impede the movement of livestock, wildlife and vehicles.[2]

Birds and wild fruit eating animals are the main cause of seed dispersal. The plant seeds can also be carried in the hooves or fur of stock animals. They may also be carried by waterways.[30]

In culture

The dog rose was the stylised rose of medieval European heraldry.[31] It is the county flower of Hampshire,[32] and Ireland's County Leitrim is nicknamed "The Wild Rose County" due to the prevalence of the dog rose in the area. Legend states the Thousand-year Rose or Hildesheim Rose, which climbs against a wall of Hildesheim Cathedral, dates back to the establishment of the diocese in 815.[33]

The first recorded significance of the flower dates back hundreds of years ago to The Academy of Floral Games (founded in 1323), which gifted poets a sprig of dog rose to reward them for their literary excellence. Due to this ritual, the branches became increasingly popular and can be found frequently mentioned in several famous poems. Most prevalent in the United Kingdom, William Shakespeare wrote about the flower in "A Mid-Summer Night's Dream",[34] which in his time was called eglantine, though it can now also refer to Rosa rubiginosa (Sweet brier)[32]

Oberon, A Midsummer Night's Dream, Act II, Scene I quoting his words: "With sweet musk-roses and with eglantine."

Symbolically, the meaning of this shrub is quite extensive since the two dominating themes surrounding the flower are pain and pleasure.[34]

An old riddle is called "The Five Brethren of the Rose":

On a summer's day, in sultry weather

Five Brethren were born together

Two had beards and two had none

And the other had but half a one.[5]

The riddle contains an effective way of identifying the differing roses of the canina group, where the brethren refers to the five sepals of the dog-rose, two of which are whiskered on both sides, two quite smooth and the last one whiskered on one side only.[32]

The flower is one of the national symbols of Romania.

The flower has also been used as an image on many postage stamps across Europe. Such as Rosa canina Switzerland, 1945. Dog Rose ('Rosa canina) Austria, 1948. Rosa canina Yugoslavia, 1955. Rosa canina Romania, 1959. Rosa canina Soviet Union, 1960. Hagebutte Rosa canina Germany, 1960. Great Britain, 1964. Rosa canina Czechoslovakia, 1965. International Congress of Pharmacology in Prague, Czechoslovakia 1971. Hagebutte Rosa canina Germany, 1978. Rosa canina-Cetonia aurata Hungary, 1980. Steinnype Rosa canina Norway, 1980. Dzika Rosa Poland, 1981. Rosa canina Bulgaria, 1981. Nypon ros Rosa canina Sweden, 1983. Dzika Rosa Poland, 1989. Rosa canina Greece, 1989. Rosa canina Romania, 1993. Rosa canina Turkey, 2001. SİPEK Rosa canina Slovenia, 2002. Eglantier Rosa canina Tunisia, 2003. Pasta Ruza (Rosa canina) Croatia, 2004 and Rosa canina Ukraine, 2005.[35]

References

- "Rosa canina (S) dog rose". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- Pavek, P.L.S. (November 2012). "DOG ROSE Rosa canina L. Plant Symbol = ROCA3" (PDF). plants.usda.gov. USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Pullman, WA. Retrieved 8 October 2023.

- "Burke Herbarium Image Collection". biology.burke.washington.edu. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- Genders, Roy (1994). Scented flora of the world (1st paperback ed.). London: Hale. ISBN 0-7090-5440-8. OCLC 33964778.

- William T. Stearn (1965). The five bretheren of the rose: An old botanical riddle (PDF). Vol. 2. Pittsburgh: Huntia Volume 2. pp. 180–184.

- Fujii, Takashi; Saito, Morio (September 2009). "Inhibitory effect of quercetin isolated from rose hip (Rosa canina L.) against melanogenesis by mouse melanoma cells". Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 73 (9): 1989–93. doi:10.1271/bbb.90181. PMID 19734679.

- Young, J.A.; Young, C.G. (1992). Seeds of Woody Plants of North America. Portland, OR.: Disocorides Press.

- Willmott, Ellen Ann, Parsons, Alfred (1914). The genus rosa. Vol. 2. London: John Murray. p. 212. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.106082.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - De Riek, Jan; De Cock, Katrien; Smulders, Marinus J.M.; Nybom, Hilde (2013). "AFLP-based population structure analysis as a means to validate the complex taxonomy of dog roses (Rosa section Caninae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 67 (3): 547–559. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2013.02.024. PMID 23499615.

- "A Rose Without Thorns in Assisi…". CafTours Magazine. 27 May 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2023.

- "Rosa canina Dog Rose PFAF Plant Database". pfaf.org. n.d. Retrieved 2021-11-15.

- Haas, L F (November 1995). "Rosa canina (dog rose)". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 59 (5): 470. doi:10.1136/jnnp.59.5.470. PMC 1073704. PMID 8530926.

- Elizabeth Knowles (2005). "Dog". The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860981-0.

- Howard, Michael. Traditional Folk Remedies (Century, 1987); p.133

- "Properties of dog rose". Botanical online. 19 January 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Vedel, Helge. (1962) [1960]. Trees and bushes in wood and hedgerow (reprint). Lange, Johan. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-416-61780-8. OCLC 863361796.

- Huxley, A (1992). The New RHS Dictionary of Gardening. London: Macmillan Press. ISBN 0-333-47494-5. OCLC 25202760.

- Ahmad, Naveed; Anwar, Farooq; Gilani, Anwar-ul-Hassan (1 January 2016). "Chapter 76 - Rose Hip (Rosa canina L.) Oils". Essential Oils in Food Preservation, Flavor and Safety. Academic Press: 667–675. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-416641-7.00076-6. ISBN 9780124166417. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- "Rosehip - A Foraging Guide to Its Food and Medicine". EATWEEDS. 2 December 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- "Pączki Are the Stuffed Polish Doughnuts You Need to Know About". kitchn. 16 January 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- "The Hirshon Polish Jelly Donuts for Fat Tuesday – Pączki". The Food Dictator. 16 January 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- Rusanova, M.; Rusanov, K.; Stanev, S.; Kovacheva, N.; Atanassov, I. (2015). "Total phenol content, antioxidant activity of hip extracts and genetic diversity in a small population of R. canina L. cv. Plovdiv 1 obtained by seed propagation". Agricultural Science and Technology. 7 (2): 162–166.

- Täckholm, Gunnar (1922). "Zytologische Studien über die Gattung Rosa". Acta Horti Bergiani. 7: 97–381.

- Lim, K Y; Werlemark, G; Matyasek, R; Bringloe, J B; Sieber, V; El Mokadem, H; Meynet, J; Hemming, J; Leitch, A R; Roberts, A V (2005). "Evolutionary implications of permanent odd polyploidy in the stable sexual, pentaploid of Rosa canina L". Heredity. 94 (5): 501–506. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800648. PMID 15770234.

- Stock, M.; Ustinova, J.; Betto-Colliard, C.; Schartl, M.; Moritz, C.; Perrin, N. (2011). "Simultaneous Mendelian and clonal genome transmission in a sexually reproducing, all-triploid vertebrate". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1732): 1293–9. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.1738. PMC 3282369. PMID 21993502.

- Kirk, T (1895). "The Displacement of Species in New Zealand". Transactions of the New Zealand Institute. Wellington: Royal Society of New Zealand. 28. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- Owen, S. J. (1997). Ecological weeds on conservation land in New Zealand: a database. Wellington: Department of Conservation.

- Water (DEW), Department for Environment and landscape (2019-01-29). "Who let the dog (rose) out?". www.landscape.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 2021-11-15.

- "Wild rose". Government of South Australia. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- "Pest plant - Dog rose and sweet briar rose - Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources". www.naturalresources.sa.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2019-04-19. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- Carol Klein Wild Flowers: Nature's own to garden grown, p. 104, at Google Books

- "Dog-rose". Plantlife. Archived from the original on 2023-03-09. Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- Lucy Gordan (November 2013). "Hildesheim's Medieval Church Treasures at the Met". Inside the Vatican. Archived from the original on 3 May 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Canale, Suzie. "The Meaning of the Dog-rose". blog.exoticflowers.com. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- Erkín, Özüm (October–December 2017). "Herbal Medicine in Stamps: History of Rosa Canina through Philately". Galore International Journal of Health Sciences and Research Vol.; Issue: ; Website: www.gijhsr.com Invited Review Paper P-ISSN: 2456-9321 Galore International Journal of Health Sciences and Research. 2 (4).

Further reading

- Flora Europaea: Rosa canina Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh

- Blamey, M. & Grey-Wilson, C. (1989). Flora of Britain and Northern Europe. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-40170-2.

- Vedel, H. & Lange, J. (1960). Trees and bushes. Metheun, London.

- Graham G.S. & Primavesi A.L. (1993). Roses of Great Britain and Ireland. B.S.B.I. Handbook No. 7. Botanical Society of the British Isles, London.