Dogon languages

The Dogon languages are a small closely related language family that is spoken by the Dogon people of Mali and may belong to the proposed Niger–Congo family. There are about 600,000 speakers of its dozen languages. They are tonal languages, and most, like Dogul, have two tones, but some, like Donno So, have three. Their basic word order is subject–object–verb.

| Dogon | |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Dogon people |

| Geographic distribution | Dogon country, Mali (mainly Bandiagara Region) |

| Linguistic classification | Niger-Congo?

|

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | dogo1299 |

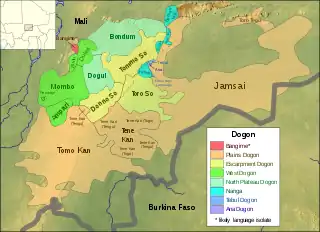

Map of the Dogon languages

| |

External relationships

The evidence linking Dogon to the Niger–Congo family is mainly a few numerals and some common core vocabulary. Various theories have been proposed, placing them with Gur, Mande, or as an independent branch, the last now being the preferred approach. The Dogon languages show very few remnants of the noun class system characteristic of much of Niger–Congo, leading linguists to conclude that they likely diverged from Niger–Congo very early.

Roger Blench comments,[1]

Dogon is both lexically and structurally very different from most other [Niger–Congo] families. It lacks the noun-classes usually regarded as typical of Niger–Congo and has a word order (SOV) that resembles Mande and Ịjọ, but not the other branches. The system of verbal inflections, resembling French is quite unlike any surrounding languages. As a consequence, the ancestor of Dogon is likely to have diverged very early, although the present-day languages probably reflect an origin some 3–4000 years ago. Dogon languages are territorially coherent, suggesting that, despite local migration histories, the Dogon have been in this area of Mali from their origin.

and:[2]

Dogon is certainly a well-founded and coherent group. But it has no characteristic Niger–Congo features (noun-classes, verbal extensions, labial-velars) and very few lexical cognates. It could equally well be an independent language family.

The Bamana and Fula languages have exerted significant influence on Dogon, due to their close cultural and geographical ties.

Blench (2015) speculates that Bangime and Dogon languages may have a substratum from a "missing" branch of Nilo-Saharan that had split off relatively early from Proto-Nilo-Saharan, and tentatively calls that branch "Plateau".[3]

Internal classification

The Dogon consider themselves a single ethnic group, but recognise that their languages are different. In Dogon cosmology, Dogon constitutes six of the twelve languages of the world (the others being Fulfulde, Mooré, Bambara, Bozo and Tamasheq).[4] Jamsay is thought to be the original Dogon language, but the Dogon "recognise a myriad of tiny distinctions even between parts of villages and sometimes individuals, and strive to preserve these" (Hochstetler 2004:18).

The best-studied Dogon language is the escarpment language Toro So (Tɔrɔ sɔɔ) of Sanga, due to Marcel Griaule's studies there and because Toro So was selected as one of thirteen national languages of Mali. It is mutually intelligible with other escarpment varieties. However, the plains languages—Tene Ka, Tomo Ka, and Jamsay, which are not intelligible with Toro so—have more speakers.

Bangime language (aka Baŋgɛri mɛ), is considered a divergent branch of Dogon by some and a possible language isolate by others (Blench 2005b).

Calame-Griaule (1956)

Calame-Griaule appears to have been the first to work out the various varieties of Dogon. Calame-Griaule (1956) classified the languages as follows, with accommodation given for languages which have since been discovered (new Dogon languages were reported as late as 2005), or have since been shown to be mutually intelligible (as Hochstetler confirmed for the escarpment dialects). The two standard languages are asterisked.

- Plains Dogon: Jamsai,*Tɔrɔ tegu, Western Plains (dialects: Togo kã, Tengu kã, Tomo kã)

- Escarpment Dogon (dialects: Tɔrɔ sɔɔ,*Tommo so, Donno sɔ aka Kamma sɔ)

- West Dogon: Duleri, Mombo, Ampari–Penange; Budu

- North Plateau Dogon: Bondum, Dogul

- Yanda

- Nanga: Naŋa, Bankan Tey (Walo), Ben Tey

- Tebul

Douyon and Blench (2005) report an additional variety, which is as yet unclassified:

Blench noted that the plural suffix on nouns suggests that Budu is closest to Mombo, so it has been tentatively included as West Dogon above. He also notes that Walo–Kumbe is lexically similar to Naŋa; Hochstetler suspects it may be Naŋa. The similarities between these languages may be shared with Yanda. These are all extremely poorly known.

Glottolog 4.3

Glottolog 4.3[5] synthesises classifications from Moran & Prokić (2013) and Hochstetler (2004). Moran & Prokić (2013) argue for a binary east-west split within Dogon, with Yanda Dom Dogon, Tebul Ure Dogon, and Najamba-Kindige as originally western Dogon languages that have become increasingly more similar to eastern Dogon languages due to intensive contact.

- Western division

- West Dogon

- North Plateau Dogon

- Dogul Dom Dogon

- Yanda-Bondum-Tebul

- Najamba-Kindige: Bondum Dom, Kindige, Najamba

- Tebul Ure Dogon

- Yanda-Ana

- Eastern division

- Escarpment Dogon

- Donno So Dogon

- Tommo So Dogon

- Toro So Dogon: Ibi So, Ireli, Sangha So, Yorno So, Youga So

- Nangan Dogon

- Plains Dogon

- Jamsay Dogon: Bama, Domno, Gono, Guru, Perge Tegu

- Toro Tegu Dogon

- Western Plains Dogon

- Tengou-Togo Dogon: Gimri Kan, Tengu Kan, Tenu Kan, Togo Kan, Woru Kan

- Tomo Kan Dogon

- Escarpment Dogon

Comparative vocabulary

Comparison of basic vocabulary words of the Dogon languages,[6] along with Bangime:[7]

| Language | Location | eye | ear | nose | tooth | tongue | mouth | blood | bone | tree | water | eat | name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yorno-So | gìrǐː | súgùrù | kín | ɛ̌n | nɛ́nɛ́, nɛ̀nɛ̌ː | kɛ̀nɛ́, áŋá | ìllîː | kǐː | náː | dǐː | káː | bôy | |

| Toro Tegu | Tabi | jìró, gìró | súgúrú | cìrⁿò-ká | jìrⁿó | lèlá | ká | néŋ | cìrá | náː, X nà | ní | lí ~ lɛ́ | ìsǒŋ |

| Ben Tey | Beni | jìré | súːrⁿù | círⁿì | ìrⁿú, ìrⁿí | lɛ̀mdɛ̂ː | mǒː, m̀bǒː | gòŋgòró | cìrⁿéy | náː, nàː-dûm | nîː | ñɛ́ | ìnìrⁿîː |

| Yanda Dom | Yanda | gìd-íyè, gìdè | sún | kìnzà | ìn | nɛ̀mdà | cɛ́nɛ́, m̀bò | jènjù | kìrⁿà | tìmè, tìmɛ̀, nìː | ínjú | ʔə́ñɛ́ ~ ʔə́ñá-lì | ín |

| Jamsay | Douentza | jìré | sûn | círⁿé | ìrⁿé | nɛ̀nɛ́ | káː | nɛ̂yⁿ | cìrⁿé | náː | níː | ñɛ́ː | bón |

| Perge Tegu | Pergué | gìré | súŋúrⁿù | kírⁿé | ìrⁿé | lɛ̀lɛ́ | káː | nɛ̂m | kìrⁿé | náː | níː | ñɛ́ː | sórⁿú |

| Gourou | Kiri | gìré | súŋùn | kírⁿé | ìrⁿé | nɛ̀nɛ́ | káː | nɛ̂yⁿ | kìrⁿé | ̀̌ | níː | ñɛ́ː | bón |

| Nanga | Anda | gìré | súŋúrⁿì | kírⁿê | ǹnɛ́, ìnɛ́, ìrⁿɛ́ | nɛ́ndɛ̀ | nɔ̌ː | gòndùgó | kìrⁿá | déː, nàː dûː | nîː | kɔ́ː | ǹnèrⁿî, ìnèrⁿî |

| Bankan-Tey | Walo | gìré | sûn | círⁿè | ŋìrⁿɛ́, ñìrⁿɛ́ | lɛ̀mbìrɛ̂ | mbǔː | gòŋgòró | kìrⁿěy | nàː-dûm | nîː | ñɛ́ | ŋìnnîː, ñìnnîː |

| Najamba | Kubewel-Adia | gìró ~ gìré | súnùː ~ súnìː | kìnjâː ~ kìnjɛ̂ː | ìnɔ̌ː ~ ìnɛ̌ː | nɛ̌ndɔ̀ː ~ nɛ̌ndɛ̀ː | ìbí-ŋgé ~ ìbí | gěn-gé ~ gěn | kìná-ŋgó ~ kìná | nǐː ~ nìː-mbó | íŋgé ~ íŋgé, ínjé ~ ínjé | kwɛ́ | ínèn ~ ínèn |

| Tommo-So | Tongo-Tongo | gìré | súgúlú | kínú | ìnú | nííndɛ́ | kɛ̀nnɛ́, áŋá | ìlìyé | kìyé | tímɛ́ | díí | ńyɛ́ | bóy |

| Togo-Kan | Koporo-pen | gìré | súgúrú | kírⁿí | ìrⁿí | nɛ́nɛ́ | káⁿ | nɛ́ | kìrⁿí | náː | díː | ñíː ~ ñíː | bɔ́ⁿ |

| Mombo | Songho | gírè | súgúlí kìjìkìjì | kínjà | ínnì | nèːndé | dónì | gèːŋgé | gàːwⁿěː | tíníŋgɔ̀ | mîː | ɲɛ́ː | íní |

| Bangime[7] | ɡìré | tàŋà | súmbí-rì | n nóɔ́ n síìⁿ | nóɔ́ n ʒɛ̀rí | nɔ́ɔ̀ | ʒíì | nnòɔ̀rɛ̀ | dʷàà, dʷàɛ̀ | ɥíè | dì-á | (màá) níì |

Numerals

Comparison of numerals in individual languages:[8]

| Language | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dogulu Dom (1) | tɔ̀mɔ̀ | nééɡè | táándù | kɛ́ɛ́sɔ̀ | ǹó | kúlè | sɔ́ɔ́wɛ̀ | sèèlé | tùùwɔ́ | pɛ́ɛ̀l |

| Dogul Dom Dogon (2) | tomo | nɛiɡe | taandu | kɛɛso | n'nɔ | kuloi | sɔɔi | seele | tuwɔ | pɛɛl |

| Tommo So Dogon | tíí (túmɔ́ as a modifier) | néé | tààndú | nǎy | ǹnɔ́ | kúlóy | sɔ́y | ɡáɡìrà | túwwɔ́ | pɛ́l |

| Donno So Dogon | tí (for counting), túru | lɛ̀y | tàːnu | này | nùmoro / nnɔ | kúlóy / kulei | sɔ̀y | ɡàɡara | tùo / tuɡɔ | pɛ́lu |

| Jamsay Dogon | túrú | lɛ̌y / lɛ̀y | tǎːn / tàːn | nǎyⁿ / nàyⁿ * | nǔːyⁿ / nùːyⁿ | kúróy | sûyⁿ | ɡáːrà | láːrúwà / láːrwà | pɛ́rú |

| Toro So Dogon (1) | tíì (for counting), túrú | lɛ́j | tàánú | nàjí | nùmɔ́r̃ɔ́ | kúlòj | sɔ́j | ɡáárà | túwɔ́ | pɛ́rú |

| Toro So Dogon (2) | tíírú (for counting), túrú | léí | táánú | náí | númɔ́rɔ́n | kúlóí | sɔ́í | ɡáɡárá | túwɔ́ | pɛ́lú |

| Toro Tegu Dogon | túrú | lɛ̌y | tǎːlí | nǎyⁿ * | nǔːyⁿ | kúréy | sóyⁿ | ɡáːrà | láːrà | pɛ́ró |

| Bankan Tey Dogon | tùmá | jǒj | tàːní | nìŋŋějⁿ | nùmmǔjⁿ | kúròj | síjⁿɔ̀jⁿ | ɡáːràj | tèːsúm | pɛ́ːrú |

| Ben Tey Dogon | tùmɔ́: | yěy | tàːnú | nǐːyⁿ | nùmǔyⁿ | kúròy | súyⁿɔ̀yⁿ | ɡáːrày | tèːsǐm | pɛ́rú |

| Mombo Dogon | yɛ̀ːtáːŋɡù / tíːtà (in counting) | nɛ́ːŋɡá | táːndì | kɛ́ːjɔ́ | núːmù | kúléyⁿ | sɔ́ːlì | séːlè | tóːwà | pɛ́ːlù |

| Najamba-Kindige | kúndé | nôːj | tàːndîː | kɛ́ːdʒɛ̀j | nùmîː | kúlèj | swɛ̂j | sáːɡìː | twâj | píjɛ́lì |

| Nanga Dogon | tùmâ | wǒj | tàːndǐː | nɔ̌jⁿ | nìmǐː | kúrê | sújɛ̂ | ɡáːrɛ̀ | tèːsǐː | pɛ́ːrú |

| Togo Kan Dogon (1) | tí | lɔ́y | tàán, tàánú | nǎyⁿ | núnɛ́ɛ́ⁿ | kúréé | sɔ́ɔ̀ | sìláà | túwáà | pɛ́rú |

| Togo Kan Dogon (2) | tí | lɔ́yì | tánn | náɲì | númɛ̀ | kúlèn | sɔ́ | sílà | túwà | pɛ́lì |

| Yanda Dom Dogon | tùmá: | nɔ́ː / nó | táːndù | cɛ́zɔ̀ | nûm | kúlé | swɛ́ː | sáːɡè | twâː | píyél |

See also

- Languages of Mali

- Dogon word lists (Wiktionary)

Notes

- Dogon Languages Archived June 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved May 19, 2013

- Roger Blench, Niger-Congo: an alternative view

- Blench, Roger. 2015. Was there a now-vanished branch of Nilo-Saharan on the Dogon Plateau? Evidence from substrate vocabulary in Bangime and Dogon. In Mother Tongue, Issue 20, 2015: In Memory of Harold Crane Fleming (1926–2015).

- The last is not mentioned in Hochstetler's sources.

- Glottolog 4.3.

- Heath, Jeffrey; McPherson, Laura; Prokhorov, Kirill; Moran, Steven. 2015. Dogon Comparative Wordlist. Unpublished Manuscript.

- Heath, Jeffrey. 2013. Bangime and Dogon Comparative Wordlists. m.s.

- Chan, Eugene (2019). "The Niger-Congo Language Phylum". Numeral Systems of the World's Languages.

References

- Bendor-Samuel, John & Olsen, Elizabeth J. & White, Ann R. (1989) 'Dogon', in Bendor-Samuel & Rhonda L. Hartell (eds.) The Niger–Congo languages: A classification and description of Africa's largest language family (pp. 169–177). Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America.

- Bertho, J. (1953) 'La place des dialectes dogon de la falaise de Bandiagara parmi les autres groupes linguistiques de la zone soudanaise,' Bulletin de l'IFAN, 15, 405–441.

- Blench, Roger (2005a). "A survey of Dogon languages in Mali: Overview". OGMIOS: Newsletter of Foundation for Endangered Languages. 3.02 (26): 14–15. Retrieved 2011-06-30..

- Blench, Roger (2005b) 'Baŋgi me, a language of unknown affiliation in Northern Mali', OGMIOS: Newsletter of Foundation for Endangered Languages, 3.02 (#26), 15–16. (report with wordlist)

- Calame-Griaule, Geneviève (1956) Les dialectes Dogon. Africa, 26 (1), 62–72.

- Calame-Griaule, Geneviève (1968) Dictionnaire Dogon Dialecte tɔrɔ: Langue et Civilisation. Paris: Klincksieck: Paris.

- Heath, Jeffrey (2008) A grammar of Jamsay. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Hochstetler, J. Lee; Durieux, J. A.; Durieux-Boon, E. I. K., eds. (2004). Sociolinguistic Survey of the Dogon Language Area (PDF). Retrieved 2021-02-22.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Moran, Steven; Prokić, Jelena (2013). "Investigating the Relatedness of the Endangered Dogon Languages". Literary and Linguistic Computing. University of Zurich. 28 (4): 676–691. doi:10.1093/llc/fqt061.

- Plungian, Vladimir Aleksandrovič (1995) Dogon (Languages of the world materials vol. 64). München: LINCOM Europa

- Williamson, Kay & Blench, Roger (2000) 'Niger–Congo', in Heine, Bernd and Nurse, Derek (eds) African Languages – An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University press, pp. 11–42.

External links

- Dogon and Bangime Linguistics

- Dogon linguistics website

- Dogon languages on Rogerblench.info (includes linguistic data and pictures)

- Dogon Languages and Linguistics An (sic) Comprehensive Annotated Bibliography Abbie Hantgan (2007)