Dolphinarium

A dolphinarium is an aquarium for dolphins. The dolphins are usually kept in a pool, though occasionally they may be kept in pens in the open sea, either for research or public performances. Some dolphinariums consist of one pool where dolphins perform for the public, others are part of larger parks, such as marine mammal parks, zoos or theme parks, with other animals and attractions as well.

While cetaceans have been held in captivity since the 1860s, the first commercial dolphinarium was opened only in 1938. Their popularity increased rapidly until the 1960s. Since the 1970s, increasing concern for animal welfare led to stricter regulation, which in several countries ultimately resulted in the closure of some dolphinariums. Despite this trend, dolphinariums are still widespread in Europe, Japan and North America.

The most common species of dolphin kept in dolphinariums is the bottlenose dolphin, as it is relatively easy to train and has a long lifespan in captivity. While trade in dolphins is internationally regulated, other aspects of keeping dolphins in captivity, such as the minimum size and characteristics of pools, vary among countries.[1] Though animal welfare is perceived to have improved significantly over the last few decades, many animal rights groups still consider keeping dolphins captive to be a form of animal abuse.

History

Though cetaceans have been held in captivity in both North America and Europe by 1860—Boston Aquarial Gardens in 1859 and pairs of beluga whales in Barnum's American Museum in New York City museum—[2][3] dolphins were first kept for paid entertainment in the Marine Studios dolphinarium founded in 1938 in St. Augustine, Florida. It was here that it was discovered that dolphins could be trained to perform tricks. Recognizing the success of Marine Studios, more dolphinariums began keeping dolphins for entertainment. In the 1960s, keeping dolphins in zoos and aquariums for entertainment purposes increased in popularity after the 1963 Flipper movie and subsequent Flipper television series. In 1966, the first dolphin was exported to Europe. In these early days, dolphinariums could grow quickly due to a lack of legislation and lack of organised animal welfare.

New legislation, most notably the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act in the United States, combined with a more critical view on animal welfare, forced many dolphinariums around the world to close. A prominent example is the United Kingdom; in the early 1970s there were at least 36 dolphinariums and traveling dolphin shows, however, the last dolphinarium closed its doors in 1993.[4] The last dolphinarium in Hungary was closed in 1992. In 2005 both Chile and Costa Rica prohibited keeping cetaceans captive.[1] However, around 60 dolphinariums currently exist across Europe, of which 34 are within the EU.[5] Japan, Mexico and the United States are also home to a relatively large number of dolphinariums.

Design

Many varied designs exist, but basic dolphinarium design for public performances often consists of stands for the public around a semi-circular pool, sometimes with glass walls which allow underwater viewing, and a platform in the middle from which the trainers direct and present the show.

The water in the pools has to be constantly filtered to keep it clean for the dolphins and the spectators, and the temperature and composition of the water has to be controlled to match the conditions dolphins experience in the wild. In the absence of a common international regulation, guidelines regarding the minimum size of the pools vary between countries.[1] To give an indication of pool sizes, the European Association for Aquatic Mammals recommends that a pool for five dolphins should have a surface area of 275 m2 (2,960 sq ft) plus an additional 75 m2 (810 sq ft) for every additional animal, have a depth of 3.5 m (11 ft) and have a water volume of at least 1,000 m3 (35,000 cu ft) with an additional 200 m3 (7,100 cu ft) for every additional animal. If two of these three conditions are met, and the third is not more than 10% below standard, the EAAM considers the pool size to be acceptable.[6]

The Brookfield Zoo dolphinarium in Chicago

The Brookfield Zoo dolphinarium in Chicago

The Festa Dolphinarium in Varna, Bulgaria

The Festa Dolphinarium in Varna, Bulgaria Dolphin show in Marineland, Niagara

Dolphin show in Marineland, Niagara

Animals

Species

Various species of dolphins are kept in captivity as well as several other small whale species such as harbour porpoises, finless porpoises and belugas, though in those cases the word dolphinarium may not be fitting as these are not true dolphins. Bottlenose dolphins are the most common species of dolphins kept in dolphinariums as they are relatively easy to train, have a long lifespan in captivity and a friendly appearance. Hundreds if not thousands of bottlenose dolphins live in captivity across the world, though exact numbers are hard to determine. Orcas are well known for their performances in shows, but the number of orcas kept in captivity is very small, especially when compared to the number of bottlenose dolphins, with only 44 captive orcas being held in aquaria as of 2012.[7] Of all orcas kept in captivity, the majority are located in the various SeaWorld parks in the United States. Other species kept in captivity are spotted dolphins, gray whales, false killer whales, pilot whales and common dolphins, Commerson's dolphins, as well as rough-toothed dolphins, but all in much lower numbers than the bottlenose dolphin. There are also fewer than ten Amazon river dolphins, Risso's dolphins, or tucuxi in captivity. There are few to almost no spinner dolphins in captivity at the time. Two unusual and very rare hybrid dolphins (wolphins, a cross between the bottlenose dolphin and the false killer whale) are kept at the Sea Life Park in Hawaii. Also two common/bottlenose hybrids reside in captivity: one at Discovery Cove and the other SeaWorld San Diego.

Trade and capture

In the early days, many bottlenose dolphins were wild-caught off the coast of Florida. Though the Marine Mammal Protection Act, established in 1972, allows an exception for the collection of dolphins for public display and research purposes when a permit is obtained, bottlenose dolphins have not been captured in American waters since 1989. In most Western countries, breeding programs have been set up to provide the dolphinariums with new animals. To achieve a sufficient birth rate and to prevent inbreeding, artificial insemination (AI) is occasionally used. The use of AI also allows dolphinariums to increase the genetic diversity of their population without having to bring in any dolphins from other facilities.

The trade of dolphins is regulated by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (also known as the Washington Convention or CITES). Endangered dolphin species are included in CITES' Appendix I, in which case trade is permitted only in exceptional circumstances. Species considered not to be threatened with extinction are included in Appendix II, in which case trade "must be controlled in order to avoid utilization incompatible with their survival". Most cetacean species traded for display in captivity to the public or for use in swimming with dolphins and other interaction programs are listed on Appendix II.[1]

However, live dolphins trade still continues. A live bottlenose dolphin is estimated to be worth between a few thousand to several tens of thousands of US dollars, depending on age, condition and prior training. Captures are reported to be on the rise in the South Pacific and the Caribbean,[8] Cuba has also been an exporter of dolphins in recent years, this being organized by the Acuario Nacional de Cuba.[9] In recent years, the Solomon Islands have also allowed the collection and export of dolphins for public display facilities.[10] A 2005 law banned the export of dolphins,[11] however, this ban was seemingly overturned in 2007 when some 28 dolphins were shipped to Dubai.[12] Some, mainly Japanese, dolphinariums obtain their dolphins from local drive hunts, though several other countries in Asia also import dolphins from Japan. Several American dolphinariums had also done so. This practice was halted in 1993, when the US National Marine Fisheries Service refused a permit for Marine World Africa USA to import four false killer whales caught in a Japanese drive hunt.

Criticism and legal bans

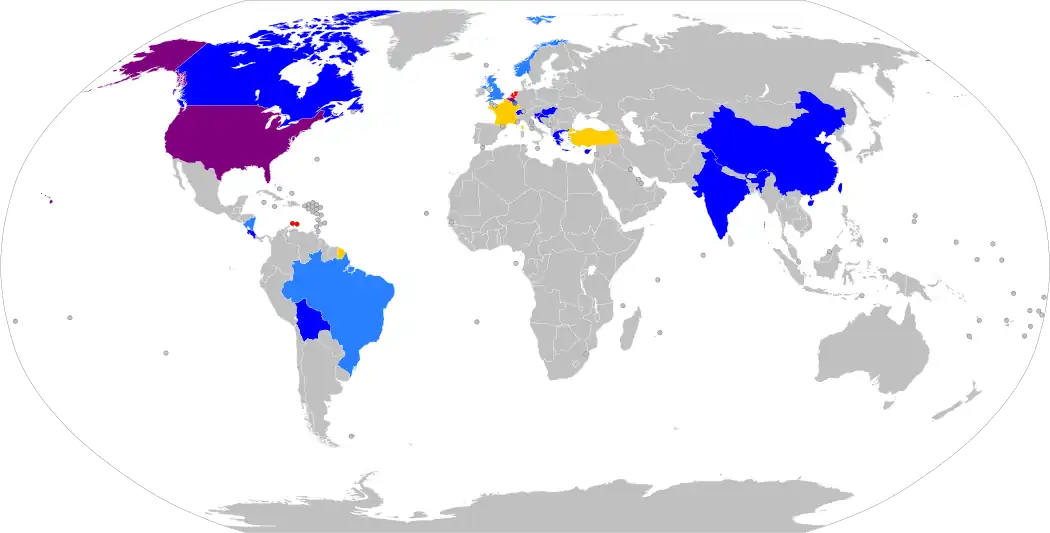

| | Nationwide ban on dolphinariums/marine mammal captivity | | De facto nationwide ban on dolphinariums/marine mammal captivity due to strict regulations |

| | Some subnational bans on dolphinariums/marine mammal captivity | | Dolphinariums/marine mammal captivity are currently being phased out ahead of a nationwide ban |

| | Dolphinariums/marine mammal captivity legal | | No data |

Animal welfare

Many animal welfare groups such as the World Animal Protection consider keeping dolphins in captivity to be a form of animal abuse. The main arguments are that dolphins do not have enough freedom of movement in pools, regardless of pool size, (in the wild, dolphins swim hundreds of miles every day) and do not get enough stimulation. Dolphins often show repetitive behavior in captivity and sometimes become aggressive towards other animals or people. In some cases, the behavior of dolphins in captivity also results in their own death.[13]

The lifespan of dolphins in captivity is another subject of debate. Research has shown that there is no significant difference between wild and captive survival rates for bottlenose dolphins.[14] This does not, however, reflect a global state of affairs: for example, bottlenose dolphins in captive facilities in Jamaica suffer from extremely high mortality rates.[15]

Some scientists suggest that the "unusually high" intelligence of dolphins[16] means that they should be recognized as "non-human persons".[17] In 2013, the Indian Ministry of Environment and Forests prohibited the captivity of dolphins on these grounds, finding it "morally unacceptable to keep them captive for entertainment purpose".[16]

Legal bans or restrictions relating to keeping cetaceans in captivity

In 2019, the Ending the Captivity of Whales and Dolphins Act became law in Canada.[18][19] Two facilities would be affected, Marineland of Canada and the Vancouver Aquarium. When passed in June 2019, Marineland was reported to have 61 cetaceans, while the Vancouver Aquarium had just one dolphin remaining. The law has a grandfather clause, permitting those cetaceans already in captivity to remain where they are, but breeding and further acquisition of cetaceans is prohibited, subject to limited exceptions.[20]

According to animal rights organizations that monitor the subject, the following jurisdictions have full or partial bans on keeping dolphins in captivity: Bolivia, China, Canada, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Hungary, India, Slovenia, Switzerland, Turkey,[21] and the American states California, New York, and South Carolina.[22][23] Other countries have laws so restrictive that is virtually impossible to keep cetaceans in captivity: Brazil, Luxembourg, Nicaragua, Norway, and the United Kingdom.[24] France tried to ban keeping or breeding cetaceans in captivity in 2017,[25] but the ban was overturned on technical grounds by the Conseil d'État in 2018.[26] On 29 September 2020, Environment Minister Barbara Pompili announced that France's three remaining dolphinariums would be closed within the next 7 to 10 years, and no new dolphinariums could be opened, and no new marine mammals could be bred or imported.[27] A month earlier on 31 August 2020, the Brussels Capital Region (which doesn't currently have any dolphinariums), announced it was working on a ban on any future creation of dolphinariums to safeguard the welfare of any marine mammals that might end up being kept within its territory.[28]

See also

- List of dolphinariums

- Marine mammal park

- Category:Films about dolphins

Notes

- "UNEP:Guidelines and criteria associated with marine mammal captivity". 2006. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- The Whale Sanctuary Project, Back to Nature (2017-06-06). "How the Beluga Business Began | The Whale Sanctuary Project | Back to Nature". The Whale Sanctuary Project. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- "150 Years Ago, a Fire in P.T. Barnum's Museum Boiled Two Whales Alive | Smart News | Smithsonian". Smithsonianmag.com. 2015-07-20. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- "In the golden heyday of the industry, there were at least 36 assorted dolphinaria or itinerant dolphin shows in the UK.", quote from The rose-tinted menagerie

- Oceancare:Dolphinariums in Europe Archived 2010-06-13 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved November 16, 2009

- Recommended EAAM dolphin housing standards Archived August 22, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 22 November 2009

- Orcas in Captivity - A look at killer whales in aquariums and parks Archived 2007-06-02 at the Wayback Machine (when viewed 23rd of November 2009)

- The Humane Society: Held Captive: Developing Nations, (2009), retrieved 22 November 2009

- "But it is in Fidel Castro's revolutionary Cuba that dolphin catching in South America has been given a new lease of life, under the auspices of the quasi state-run enterprise Acuario Nacional.", quote from The rose-tinted menagerie

- HONIARA, Solomon Islands (Reuters) - A cargo plane arrived in the lawless Solomon Islands Monday to pick up wild dolphins captured to order for a Mexican syndicate in what activists have blasted as an environmental crime, regional media reported. Developments on dolphin capture Archived 2006-05-11 at the Wayback Machine

- "Solomon Islands law banning the export of dolphins" (PDF). Keiko.com. 2018-02-21. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- The Associated Press / International Herald Tribune Solomon Islands dolphins exported to Dubai; protests mount, article retrieved October 25, 2007.

- Marine animals in captivity, World Animal Protection. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- Willis, K. 2007. "Life Expectancy of Bottlenose Dolphins in Alliance of Marine Mammal Parks and Aquariums' North American Member Facilities: 1990 - present". Presented at the 2007 meeting of the Alliance of Marine Mammal Parks and Aquariums.

- Environmental Management Consultants Ltd. (2007), Review of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) For the Proposed Dolphin Park in Paradise, Hanover Archived 2009-11-23 at the Wayback Machine, page 3, section Mortalities. Article retrieved November 20, 2009.

- "No, India did not just grant dolphins the status of humans". io9. 15 August 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- "Dolphins deserve same rights as humans, say scientists". BBC News. 21 February 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- Holly Lake (2019-06-12). "An end to the captivity of whales and dolphins". National Magazine. The Canadian Bar Association. Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- "Ending the Captivity of Whales and Dolphins Act" (PDF). Government of Canada. 2019. Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- Laura Howells (2019-06-10). "'A more humane country': Canada to ban keeping whales, dolphins in captivity". CBC News. Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- "Turkish parliament approves animal rights bill". Anadolu Agency. 9 July 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- Megan Sutton (2019-06-07). "Sea Change: The Wave of Support for Ending Dolphin Captivity". Sierra Club Canada. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- "The Current State of Cetacean Captivity". We Animals Media. 2019-11-19. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- "Major victory for dolphins, whales and porpoises in Canada!" (Press release). Society for the Protection of Animals Canada. 2019-06-10. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- "France bans captive breeding of dolphins and killer whales". BBC News. 2017-05-07. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- "France scraps ban on breeding dolphins in captivity". RFI. 2018-01-30. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- "France to ban use of wild animals in circuses". Reuters. 29 September 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- Jules Johnston (31 August 2020). "Brussels moves to ban dolphin keeping in the region". The Brussels Times. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

Further reading

- Johnson, William (April 1994). The Rose-tinted Menagerie. Heretic Books. ISBN 978-0-946097-28-9.