Dordrecht

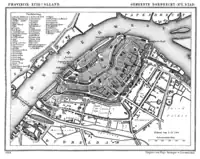

Dordrecht (Dutch: [ˈdɔrdrɛxt] ⓘ), historically known in English as Dordt (still colloquially used in Dutch, pronounced [dɔrt] ⓘ) or Dort, is a city and municipality in the Western Netherlands, located in the province of South Holland. It is the province's fifth-largest city after Rotterdam, The Hague, Zoetermeer and Leiden, with a population of 119,115.

Dordrecht

Dordt | |

|---|---|

City and municipality | |

Augustijnenkamp Historic city centre Bleijenhoek City hall | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

.svg.png.webp) Location in South Holland | |

Dordrecht Location within the Netherlands  Dordrecht Location within Europe | |

| Coordinates: 51°47′45″N 04°40′42″E | |

| Country | Netherlands |

| Province | South Holland |

| City Hall | Dordrecht City Hall |

| Government | |

| • Body | Municipal council |

| • Mayor | Wouter Kolff (VVD) |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 99.47 km2 (38.41 sq mi) |

| • Land | 79.01 km2 (30.51 sq mi) |

| • Water | 20.46 km2 (7.90 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1 m (3 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Municipality | 119,115 |

| • Density | 1,508/km2 (3,910/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 237,848 |

| • Metro | 286,833 |

| Demonym | Dordtenaar |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postcode | 3300–3329 |

| Area code | 078 |

| Website | www |

The municipality covers the entire Dordrecht Island, also often called Het Eiland van Dordt ("the Island of Dordt"), bordered by the rivers Oude Maas, Beneden Merwede, Nieuwe Merwede, Hollands Diep, and Dordtsche Kil. Dordrecht is the largest and most important city in the Drechtsteden and is also part of the Randstad, the main conurbation in the Netherlands.

Dordrecht is the oldest city in Holland and has a rich history and culture.

Etymology

The name Dordrecht comes from Thuredriht (circa 1120), Thuredrecht (circa 1200). The name seems to mean 'thoroughfare'; a ship-canal or -river through which ships were pulled by rope from one river to another, as here from the Dubbel to the Merwede, or vice versa. Earlier etymologists had assumed that the 'drecht' suffix came from Latin 'trajectum', a ford, but this was rejected in 1996.[6] The Drecht is now supposed to have been derived from 'draeg', which means to pull, tow or drag. Inhabitants of Dordrecht are Dordtenaren (singular: Dordtenaar).

Dordrecht is informally called Dordt by its inhabitants. In earlier centuries, Dordrecht was a major trading port and was called Dort in English.[7]

History

Early history

The city was formed along the Thure river, in the midst of peat marshes. This river was a branch of the river Dubbel, which is part of the massive Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta complex, near the current Bagijnhof. Around 1120 reference to Dordrecht was made by a remark that count Dirk IV of Holland was murdered in 1049 near "Thuredrech".

Dordrecht was granted city rights by William I, Count of Holland, in 1220, making it the oldest city in the present province of South Holland. In fact, Geertruidenberg was the first city in the historical county of Holland to receive city rights, but this municipality currently is part of the province of North Brabant.

In the 12th and 13th centuries, Dordrecht developed into an important market city because of its strategic location. It traded primarily in wine, wood and cereals. Dordrecht was made even more important when it was given staple right in 1299.

In 1253 a Latin school was founded in Dordrecht. It still exists today as the Johan de Witt Gymnasium and is the oldest gymnasium in the Netherlands. From 1600 to 1615 Gerhard Johann Vossius was rector at this school.

On 18–19 November 1421, the Saint Elisabeth's flood flooded large parts of southern Holland, causing Dordrecht to become an island. It was commonly said that over 10,000 people died in the flood, but recent research indicates that it was probably less than 200 people.[8]

On 29 June 1457, the city was devastated by a fire which started in Kleine Spuistraat, destroying many buildings, including the Grote Kerk.[9][10][11]

Union of Dordrecht

In 1572, four years into the Dutch Revolt, representatives of all the cities of Holland, with the exception of Amsterdam, as well as the Watergeuzen, represented by William II de la Marck, gathered in Dordrecht to hold the Eerste Vrije Statenvergadering ("First Assembly of the Free States"), also known as the Unie van Dordrecht ("Union of Dordrecht"). This secret meeting, called by the city of Dordrecht, was a rebellious act since only King Philip II or his stadtholder, at that time the Duke of Alba, were allowed to call a meeting of the States of Holland.

During the meeting, the organization and financing of the rebellion against the Spanish occupation was discussed, Phillip II was unanimously denounced, and William of Orange was chosen as the rightful stadtholder and recognized as the official leader of the revolt. Orange, represented at the meeting by his assistant Philips of Marnix, was promised financial support of his struggle against the Spanish and at his own request, freedom of religion was declared in all of Holland.

The gathering is regarded as the first important step towards the free and independent Dutch Republic.[12] Other important gatherings such as the Union of Brussels (1577) and the Union of Utrecht (1579) paved the way for official independence of the Dutch Republic, declared in the Act of Abjuration in 1581.

The Union of Dordrecht was held in an Augustinian monastery, nowadays simply called het Hof ("the Court"). The room in which the meeting was held is called de Statenzaal ("The Hall of States") and features a stained glass window in which the coats of arms of the twelve cities that were present at the meeting can be seen.

Synod of Dordrecht

From 13 November 1618 to 9 May 1619, an important Dutch Reformed Church assembly took place in Dordrecht, referred to as the Synod of Dordrecht.[13] The synod attempted, and succeeded, to settle the theological differences of opinion between the central tenets of Calvinism, and a new school of thought within the Dutch Reformed Church known as Arminianism, named for its spiritual leader Jacobus Arminius. Arminius' followers were also commonly known as Remonstrants, after the 1610 Five Articles of Remonstrance which outlined their points of dissent from the church's official doctrine. They were opposed by the Contra-Remonstrants, or the Gomarists, who were led by Dutch theologian Franciscus Gomarus.

During the Twelve Years' Truce, this in essence purely theological conflict between different factions of the church had in practice spilled over into politics, dividing society along ideological lines, and threatening the existence of the young republic by repeatedly bringing it to the brink of civil war.[14]

The synod was attended by Gomarist Dutch delegates and also by delegates from Reformed churches in Germany, Switzerland, and England. Though it was originally intended that the synod would bring agreement on the doctrine of predestination among all the Reformed churches, in practice this Dutch synod was mainly concerned with problems facing the Dutch Reformed Church.

The opening sessions dealt with a new Dutch translation of the Bible, a catechism, and the censorship of books. The synod then called upon representatives of the Remonstrants to express their beliefs. The Remonstrants refused to accept the rules established by the synod and eventually were expelled from the church.

The synod then studied the theology of the Remonstrants and declared that it was contrary to Scripture. The Canons of Dort were produced; they discussed in detail in five sections the errors of the Remonstrants that were rejected as well as the doctrines that were affirmed. The doctrines affirmed were that predestination is not conditional on belief; that Christ did not die for all; the total depravity of man; the irresistible grace of God; and the impossibility of falling from grace. These canons of Dort, along with the Belgic Confession and the Heidelberg Catechism, remain the theological basis of the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands.

Following the synod, two hundred Remonstrant ministers were deposed from their office, of which eighty were banished. The political leaders of the Remonstrant movement were arrested and one of them beheaded on May 14, 1619.[15] It was only after the death of Prince Maurice in 1625 that the persecution of the Remonstrants ceased.[16]

Diminishing economic importance

During the Eighty Years' War merchants from Dordrecht were involved in taking control and founding sugar cane plantations in the West Indies. At the end of the 17th century this led to a stable sugar refining industry in Dordrecht. This flourished in the 18th century, when Dordrecht had 16 sugar refineries, as opposed 120 in Amsterdam and 40 in Rotterdam. Dordrecht still has a few buildings purposely designed as a sugar refinery, e.g. the imposing Sugar Refinery Stokholm.[17]

Overall, the economic importance of Dordrecht began to wane in the 18th century, and Rotterdam became the main city in the region.

The Patriots movement

From 1780 to 1787, Dordrecht was home to the Patriots faction which intended to remove the hereditary Stadtholder position held by the House of Orange-Nassau.

The Netherlands was after all a republic de jure. Soon after, more cities followed and William V fled from Holland. But his brother-in-law, King Frederick William II of Prussia, came to the aid of William V and on 18 September 1787, Dordrecht capitulated to Prussian troops. The Patriots were defeated and Willem V was restored in his position as Stadtholder.

In the Kingdom of the Netherlands (1815–2023)

The French period (1795-1813) had ruined Dordrecht just like it ruined the other cities of Holland. However, Dordrecht continued to be a decent sea harbor. For ocean-going ships it was even easier to reach the harbor of Dordrecht than that of Rotterdam. This situation changed in 1829, when the Voorne Canal was opened. Meanwhile, the way that Dordrecht profited from the trade with the Dutch East Indies probably obscured the fact that it was losing the maritime competition with Rotterdam. The end of Dordrecht as a first rate sea harbor came about when the Nieuwe Waterweg became fully usable in 1883.[18] Compared to Dordrecht, Rotterdam sent about four times as much cargo up the Rhine to Germany in 1875. In 1895 this was 30 times as much and in 1910 about 200 times. In absolute numbers cargo from Dordrecht declined by more than 50%.[18]

In the early 19th century, Dordrecht was a major center for shipbuilding. It was also a center of the Dutch timber market. As a smaller town, wages were lower than in Amsterdam and Rotterdam. It all made that many shipping lines that sailed to the East Indies for the Netherlands Trading Society (NTS) had their ships built in Dordrecht. Shipbuilders and shipping lines from Dordrecht profited disproportionally from the NTS policies. From about 1850 to 1876, the NTS gradually stopped its protection of Dutch shipping.[18]

The traditional (cane) sugar refinining industry of Dordrecht would not survive the industrial revolution. However, in 1861 Dordrecht Sugar Factory became operational as second modern beet sugar factory of the Netherlands.

Throughout the centuries, Dordrecht held a key position in the defense of Holland. It hosted an army division well into the 20th century. During the mobilization of August 1939, infantry and artillery were sent to Dordrecht to defend the island. When the Germans invaded the Netherlands on 10 May 1940, German paratroopers landed in Dordrecht. After fierce fighting they overtook the bridges Dordrecht-Moerdijk and Dordrecht-Zwijndrecht. Many buildings in Dordrecht were destroyed. At the end of the Second World War, during the winter of 1944–45, Dordrecht and its surroundings were in the middle between the opposing armies. The border between occupied and liberated regions ran along the Hollands Diep. Dordrecht was finally liberated by the Canadian Army.

In 1970, the municipality Dubbeldam (then ca. 10,000 inhabitants) and the southern part of the municipality of Sliedrecht were incorporated into Dordrecht, making Dordrecht Island one municipality.

Districts

Dordrecht is divided into 27 districts, neighbourhoods and hamlets:

|

|

Demography

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1354 | 10,000 | — |

| 1398 | 7,500 | −0.65% |

| 1514 | 11,200 | +0.35% |

| 1555 | 10,000 | −0.28% |

| 1560 | 12,500 | +4.56% |

| 1622 | 18,270 | +0.61% |

| 1632 | 20,600 | +1.21% |

| 1665 | 20,000 | −0.09% |

| 1732 | 18,000 | −0.16% |

| 1795 | 18,014 | +0.00% |

| Source: Lourens & Lucassen 1997, pp. 103–105 | ||

In 2021, around 19,35% of the population of Dordrecht was of non-Western origin. Between 2005 and 2008, this number has not changed. The allochthonous population consists for a large part of young people while the indigenous population has started to age very quickly. Over six thousand Turks live in Dordrecht, many of whom are originally from Kayapınar.

According to the Social Geographical Office of Dordrecht, the population consisted of the following ethnic groups in 2005[19] and 2008:[20]

| Ethnic group | 01-01-2005 | 01-01-2008 |

|---|---|---|

| Native Dutch | 86,594 | 86,611 |

| Western foreigner | 11,610 | 11,580 |

| Turks | 6,113 | 6,326 |

| Moroccans | 2,521 | 2,611 |

| Surinamese | 2,759 | 2,796 |

| Netherlands Antilleans | 3,199 | 3,037 |

| Other non-Western foreigner | 6,528 | 5,226 |

| Total | 119,324 | 118,187 |

Culture

Due to its long and important role in Dutch history, Dordrecht has a rich culture. The medieval city centre is home to over 950 monuments.[21] The city also houses 7 historic churches and 6 museums in a relatively small area and hosts many festivals and events every year.

Places of interest

- The Onze-Lieve-Vrouwe-Kerk ('Our Dear Lady Church') or simply the Grote Kerk ('Big Church') was built between 1285 and 1470. The 65-meter tower contains a carillon with 67 bells including one weighing 9830 kilos, making it the heaviest bell in the Netherlands.

- The Augustijnenkerk ('Church of the Augustins') was built around 1293 and is currently owned by the Dutch Reformed Church. The church includes the Augustinian Monastery het Hof ('the Court') which was built in 1275 and was the location of the First Assembly of the Free States.

- The Nieuwkerk ('New Church') or St Nicolaas Kerk was built in 1175 and is, ironically considering its name, the oldest building in Dordrecht.

- The Munt van Holland ('Mint of Holland'), mint built in 1366. The majority of the coins used in the region of Holland in the Middle Ages were struck here. Nowadays, the building houses a music school.

- Kyck over den Dyck ('View over the Dike'), the last windmill in Dordrecht. It was built in 1612 and used to produce malt that was used by Dordts beer brewers.

- The Groothoofdspoort ('Big Head's Gate') is the original city gate of Dordrecht, built in the 14th and 15th centuries. It is situated at the point where the rivers the Meuse, the Merwede, and the Rhine meet.

- Arend Maartenshof (Arend Maarten's Court), built in 1625.

- Stadhuis city hall, built in 1383.

- Statue of Ary Scheffer (1861), by Joseph Mezzara.

- Statue of Johan and Cornelis de Witt (1918), by Toon Depuis.

- River quais.

- Harbours.

- Merchant houses.

Museums

The following museums are located in Dordrecht:

- Binnenvaartmuseum, dedicated to the history of inland navigation.

- Dordrechts Museum, informally called Schilderijenmuseum (the paintings museum). Every summer, its garden, known as de Museumtuin (the Museum garden), hosts the showing of several art house films that gained significant attention in the previous year. Re-opened in late 2010 after an extensive renovation.

- Simon van Gijn museum, named after honorary citizen Simon van Gijn and winner of the museum prize 2004–2005, awarded by the Prins Bernhard Cultuurfonds.

- Nationaal Landschapskundig Museum, (National Museum of Landscaping)

- Museum 1940–1945, also known as het Verzetsmuseum (the Resistance museum).

- Het Hof, about the Dutch history

- Onderwijsmuseum, dedicated to the Dutch history of education and schools.

Events and festivals

Dordrecht hosts around 20 cultural and historical events and festivals each year. The city won the title of "Best events city of the year" in 2003[22] and was nominated for the same title in 2004 and 2005.[23][24]

Dordt in Stoom (literally: Dordt in steam) is the biggest steam event in Europe during which historical steam trains, steam boats etc. can be seen in action. It is organized every other year and attracts a quarter of a million visitors.[25] Attention is also paid to Dordrecht's art and architecture during Kunstrondje Dordt (literally: Little art circle Dordt) and Dordt Monumenteel (Dordt Monumental), which attracts around 100.000 visitors every year.

Dordrecht hosts the second largest book market[26] and the largest Christmas market in the Netherlands.[27]

Wantijfestival is an out-doors music festival that has been held annually in the second week of June since 1995. It takes place in the Wantij park and attracts around 35.000 people each year.[28] Wantij park also hosts the Wantijconcerten (Wantij concerts) that are held every Monday night in July and August. Other popular music festivals held in Dordrecht are the World Jazz dagen (World Jazz days) held annually in August or September, the Dancetour or Boulevard of Dance, which takes place on Kingsday, Big Rivers Festival, a film, music, poetry and theatre festival held in June, and the Cello festival, held every four years in the weekend of the Ascension.

Rond Uit Dordrecht, Since 2013 they do organise a four-day bicycle festival early June.

A website with a list of the festivals in the city Dordrecht: Dordrecht Festivals

Folklore

During Carnaval, Dordrecht is called Ooi- en Ramsgat (Ewe's and Ram's hole), and its inhabitants are Schapenkoppen (Sheepheads). This name originates from an old folk story. Import of meat or cattle was taxed in the 17th century. To avoid having to pay, two men dressed up a sheep they had bought outside the city walls, attempting to disguise it as a man. The sheep was discovered because it bleated as the three men (two men and one sheep) passed through the city wall gate. There is a special monument of a man and his son trying to hold a sheep disguised as a man between them, that refers to this legend. The logo of Dordrecht's professional football club FC Dordrecht includes the head of a ram and its supporters are known to sing Wij zijn de Dordtse schapenkoppen (we are the Dordtse sheep heads) during matches. There is also a cookie called Schapenkop (sheep head) which is a speciality of Dordrecht.

There are many more legends about Dordrecht. One of them is about Saint Sura, a young woman who planned on building an entire church with only three coins in her purse. She was murdered because of her supposed wealth.

Another legend is about the house called de Onbeschaamde (the Unembarrassed). It is about the three brothers Van Beveren who each wanted to build a house and decided to make a bet on who would dare to place the most risqué statue on their façade. One of the brothers, Abraham van Beveren, placed a naked little boy on his façade. However, the house that supposedly won has an empty façade today because, according to the story, the statue was so risqué that it was removed.

A well known saying about Dordrecht is Hoe dichter bij Dordt, hoe rotter het wordt (the closer to Dordrecht, the more rotten it gets). The previous mayor Noorland added to that; maar ben je er eenmaal in, dan heb je het prima naar je zin (but once you're in it, you're perfectly content). The saying can probably be explained as follows; traffic used to go by water and whoever came close to Dordrecht was obliged, according to staple right, to display their merchandise for a couple of days before being allowed to sail on. This caused loss of time and caused products to become rotten. Another explanation is derived from Bommel is rommel, bij Tiel is niet viel en hoe dichter bij Dordt hoe rotter het wordt which is supposed to be said by farmers describing the bad quality of the land close to the rivers Maas and Waal, only suitable for harvesting reed.

Nature

The Sliedrechtse Biesbosch, east of Dordrecht, and the Dordtse Biesbosch, south of Dordrecht, together form the Hollandse Biesbosch which is a part of the national park the Biesbosch, one of the largest national parks in the Netherlands and one of the last freshwater tide areas in Europe. The Dordtse Biesbosch has several recreational areas that are used for walking, rowing and swimming.

There are also several parks near the city, such as Merwepark and Wantijpark.

Sports

The Riwal Hoogwerkers Stadion is a football stadium and home ground of the local team FC Dordrecht playing in the second national league.

Dordts

Dordts is a dialect of Dutch traditionally spoken by the working class of Dordrecht. It is categorized under the Hollandic accents but also has characteristics of Zeelandic and Brabantian.

Typical features of Dordts are:

- Using the diminutive suffix -ie or -tie in cases where standard Dutch uses -je. (e.g. Standard Dutch: appeltje (“little apple”) Dordts: appeltie)

- Words borrowed from Brabantian such as akkerdere (“lit. to knock or to fit, fig. “to get along”)

- The Dutch diphthongs ei and ui tend to be pronounced more like èè and öö. Recently, the ei-sound has started to be pronounced more like ai.

In the 20th century, Dordts has slowly started to disappear as more and more people have started speaking standard Dutch. The strongest Dordts dialect is nowadays found in the working-class neighborhoods bordering the city centre.

Other

On 14 November 1992 and again on 12 November 2011, the official arrival of the popular legendary figure Sinterklaas was held in Dordrecht and broadcast on national television.

Economy

The current economy of Dordrecht is based on ship building, wood industry, and steel industry. The city has the sixth largest sea port in the Netherlands. One of the largest employers on Dordrecht Island is DuPont de Nemours (Nederland) B.V. It has 9 factories here with a workforce of 900 people.

In development are the "Learning" and "Health" Business Parks. The Learning Park is intended to have 60,000 m2 (645,834.63 sq ft) of space for educational institutions. In the Health Park, a wide range of health services will be located, with the Dordwijk Campus of the Albert Schweitzer Hospital as focal point. Other services include a blood bank, pharmacy, and mental health clinic.

Near the Health Park a new Sport Park will be built. A new large sport centre, the equivalent size of 3 soccer fields, is planned complete with gyms, skating rink, and a pool. Next to this Sport Park, a huge outdoor event terrain will be established.

Shopping

Shopping in the centre of Dordrecht is centred around the Voorstraat, the Sarisgang and the Statenplein (Staten square). The Voorstraat is 1,200 m (1,300 yd) long, making it the longest shopping street in the Netherlands.[29] Markets are held every Friday and Saturday on the Statenplein and in the Sarisgang and on Tuesday in Dubbeldam.

Government and politics

College van B&W

In February 2020[30] the College van Burgemeester en Wethouders ('Board of Mayor and Aldermen') in Dordrecht consisted of the following:

- Wouter Kolff, Mayor (VVD)

- Piet Sleeking, alderman (Beter voor Dordt)

- Peter Heijkoop, alderman (CDA)

- Marco Stam, alderman (Beter voor Dordt)

- Rik van der Linden, alderman (CU/SGP)

- Maarten Burggraaf, alderman (VVD)

Local election

The results of the 2018 municipal election in Dordrecht were as follows.

| Party | Votes in % | Seats in municipal council |

|---|---|---|

| Beter Voor Dordt | 18.4 | 8 |

| People's Party for Freedom and Democracy | 12.1 | 5 |

| Christian Democratic Appeal | 10.1 | 4 |

| Democrats 66 | 9.9 | 4 |

| GroenLinks | 9.6 | 4 |

| Christian Union-SGP | 9.0 | 4 |

| Party for Freedom | 7.7 | 3 |

| Socialist Party | 6.1 | 2 |

| United Seniors Party | 6.0 | 2 |

| Labour Party | 5.5 | 2 |

| Normal Dordt | 3.3 | 1 |

| Turnout | 51.0 | 39 |

Partner cities

Partner cities of Dordrecht are:[31]

|

|

Public transport

Dordrecht is well connected to the Dutch railroad system, and has several international connections. There are three railway stations; Dordrecht railway station, Zuid railway station and Stadspolders railway station. The train system hosts:

Four trainlines

- South-West direction Roosendaal-and further (including international to Belgium)

- South-East direction Breda, Eindhoven

- North-West direction Rotterdam, The Hague, Amsterdam

- East direction Gorinchem, Geldermalsen

The four operating trainlines serve three railway stations within the city boundaries (Dordrecht, Dordrecht Zuid, Dordrecht Stadspolders)

Main connections

- Frequent services within the Netherlands:

- Intercity line to Rotterdam, The Hague, Leiden, Amsterdam Airport Schiphol and Amsterdam (north-west)

- Intercity line to Roosendaal and on to Vlissingen (south west)

- Intercity line to Breda, Tilburg, Eindhoven, Helmond and Venlo (south east)

- Several semi-fast services and local trains originate or call at Dordrecht.

- Detailed information available from the site of the Nederlandse Spoorwegen (Dutch Railways)

- Qbuzz, the city bus company of Dordrecht, also serving Alblasserwaard, Drechtsteden and Vijfheerenlanden, and also operating the train to Gorinchem and Geldermalsen. and Arriva is part of the waterbus

- Waterbus:[32]

- line 20: Rotterdam Erasmusbrug – Krimpen aan den IJssel Stormpolder – Ridderkerk De Schans – Alblasserdam Kade – Hendrik Ido Ambacht Noordeinde - Papendrecht Westeind - Dordrecht Merwekade

- line 21: Dordrecht Hooikade – Zwijndrecht Veerplein

- line 22: Dordrecht Merwekade – Papendrecht Veerdam

- line 23: Dordrecht Merwekade – Papendrecht Oosteind – Hollandse Biesbosch – Sliedrecht Middeldiep

- line 24: Dordrecht Merwekade – Zwijndrecht Veerplein

Famous people from Dordrecht

- See also People from Dordrecht

_-_Corn%C3%A9lie_van_Zanten.jpg.webp)

The arts

- Hendrik Speuy (1575–1625) a Dutch organist and composer

- Jacob Cats (1577–1660) a Dutch poet, humorist, jurist and Grand Pensionary of Holland[33]

- Jeremias de Dekker (1610–1666) a Dutch poet[34]

- Mathias Balen (1611–1691) a Dutch historian, wrote Beschryving der Stad Dordrecht ("Description of City of Dordrecht")

- Aelbert Cuyp (1620–1691) a Dutch Golden Age painter of landscapes.[35]

- Margaretha van Godewijk (1627–1677) a Dutch Golden Age poet and painter

- Samuel Dirksz van Hoogstraten (1627–1678) a Dutch Golden Age painter, also a poet and author on art theory[36]

- Nicolaes Maes (1634–1693) a Dutch painter of genre scenes and portraits.[37]

- Godfried Schalcken (1643–1706) a Dutch genre and portrait painter[38]

- Arnold Houbraken (1660–1719) a Dutch Golden Age painter and writer

- François Valentijn (1666–1727) a Dutch minister, naturalist and author; wrote Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën about the Dutch East India Company

- Jacobus Houbraken (1698–1780) a Dutch engraver[39]

- Aart Schouman (1710–1792) Dutch painter and engraver

- Johannes Immerzeel (1776–1841) a Dutch writer and poet

- Ary Scheffer (1795–1858) a Dutch-French Romantic painter[40]

- Cornélie van Zanten (1855–1946) a Dutch opera singer, author and teacher

- Augusta Peaux (1859–1944) a Dutch poet who loved Iceland

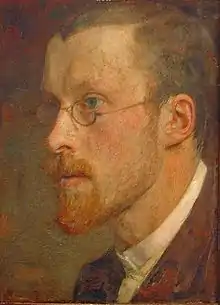

- Jan Veth (1864–1925) a Dutch painter, poet, art critic and university lecturer

- Top Naeff (1878–1953) a Dutch writer

- Allard de Ridder (1887–1966) a Dutch–Canadian conductor, violist and composer

- Peter Hurkos (1911–1988) Dutch entertainer, performed psychic feats

- Kees Buddingh' (1918–1985) a Dutch poet, TV-presenter and translator

- Jan Eijkelboom (1926–2008) a Dutch journalist and writer

- Henk Bouman (born 1951) a Dutch harpsichordist, fortepianist, conductor and composer

- Edo Brunner (born 1970) a Dutch actor and presenter[41]

- Celinde Schoenmaker (born 1989) a Dutch theatre actress and singer

- O'G3NE (formed 2007) a Dutch girl group and The Voice of Holland winners in 2014

Public thinking & public service

- Beatrix de Rijke (1421–1468) a Dutch foundling from St. Elizabeth's flood (1421)

- Gerhard Johann Vossius (1577–1649) a Dutch classical scholar and theologian[42]

- Simon de Danser (ca.1579–ca.1615) a Dutch privateer and pirate

- Jacob de Witt (1589–1674) a burgomaster of Dordrecht and the son of a timber merchant

- Jacques Specx (1588–1652) Governor General Dutch East Indies (VOC)

- brothers Cornelis de Witt (1623–1672) & Johan de Witt (1625–1672) lynched politicians.[43][44]

- Laurens de Graaf (ca. 1653–1704) a Dutch pirate, mercenary and naval officer[45]

- Conrad Theodor van Deventer (1857–1915) a lawyer and author about the Dutch East Indies

- Henriette Willemina Crommelin (1870-1957), a labor leader and temperance reformer

- Pieter Geyl (1887–1966) an historian, studied early modern Dutch history and historiography

- Cornelis Eliza Bertus Bremekamp (1888–1984) a botanist, worked in Indonesia and South Africa

- Marinus Vertregt (1897–1973) a Dutch astronomer

- Jaap Burger (1904–1986) a Dutch politician and jurist; lawyer in Dordrecht 1929 to 1942

- Henk Korthals (1911–1976) a Dutch politician and journalist

- Theo Bot (1911–1984) a Dutch politician, diplomat and jurist

- Aart Alblas (1918–1944) a Dutch navy officer, Dutch resistance member and Engelandvaarder

- Nicolaas Bloembergen (1920–2017) a Dutch-American physicist and winner of the 1981 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on nonlinear optics for laser spectroscopy

- Jan Pouwer (1924–2010) a Dutch anthropologist and academic

- Philip Scheltens (born 1957) a professor of neurology and expert on Alzheimer's disease

- Eline Slagboom (born 1960) a biologist specializing in human familial longevity and ageing

Sport

- Dirk Boest Gips (1864–1920) a Dutch sports shooter, team bronze medallist at the 1900 Summer Olympics

- Hendrik de Iongh (1877–1962) a fencer, team bronze medallist at the 1912 Summer Olympics

- brothers Geert Lotsij (1878–1959) & Paul Lotsij (1880–1910) rowers, team silver medallists at the 1900 Summer Olympics

- Piet Bouman (1892–1980) a Dutch amateur footballer, team bronze medallist at the 1912 Summer Olympics

- Karel Lotsy (1893–1959), sport leader, Dutch Olympic Head of Mission 1936/1952

- Simon Wulfse (born 1952), a strongman and drug smuggler

- Peter Smit (1961–2005), a Dutch martial artist

- Juul Ellerman (born 1965), a Dutch former footballer with 389 club caps

- Marco Boogers (born 1967), a Dutch former professional footballer with 399 club caps

- Reinier Robbemond (born 1972), a Dutch football manager and former player with 412 club caps

- Danny Makkelie (born 1983), is a Dutch FIFA football referee

- Mareno Michels (born 1984), a Dutch darts player

- Lucinda Brand (born 1989), cyclist

- Björn Vlasbom (born 1990), former professional footballer

- Maria Verschoor (born 1994), a Dutch field hockey player, team silver medallist at the 2016 Summer Olympics

- Jarno Opmeer (born 2000), a Dutch racing driver and Esports competitor

- Dilano van 't Hoff (2004-2023), a Dutch racing driver, 2021 Spanish Formula 4 Champion

Image gallery

Hofstraat

Hofstraat Grote Kerk

Grote Kerk Groothoofdspoort

Groothoofdspoort Het Hof (The Court)

Het Hof (The Court) City Hall

City Hall Pottenkade next to the Grote Kerk

Pottenkade next to the Grote Kerk Windmill 'Kyck over den Dyck'

Windmill 'Kyck over den Dyck'

port

port View to monumental buildings

View to monumental buildings square: Scheffersplein

square: Scheffersplein Sheep in the Hoefijzerstraat

Sheep in the Hoefijzerstraat View to the Wijnhaven

View to the Wijnhaven Boat: the Friedrich Voss

Boat: the Friedrich Voss

References

Citations

- "College van Burgemeester en Wethouders" [Board of mayor and aldermen]. Organen (in Dutch). Gemeente Dordrecht. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- "Kerncijfers wijken en buurten 2020" [Key figures for neighbourhoods 2020]. StatLine (in Dutch). CBS. 24 July 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- "Postcodetool for 3311GR". Actueel Hoogtebestand Nederland (in Dutch). Het Waterschapshuis. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- "Bevolkingsontwikkeling; regio per maand" [Population growth; regions per month]. CBS Statline (in Dutch). CBS. 1 January 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- "Bevolkingsontwikkeling; Regionale kerncijfers Nederland" [Regional core figures Netherlands]. CBS Statline (in Dutch). CBS. 1 January 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- W. van Osta, 'Drecht en drecht-namen', Naamkunde 28, 1-2 (Leuven 1996) 51-77

- "Dordrecht | Netherlands | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-03-24.

- J. Hendriks, 'De watersnoodrampen van 1421 en 1424', in: H. van Duinen en C. Esseboom, Verdronken dorpen boven water. Sint Elisabethsvloed 1421; geschiedenis en archeologie (Dordrecht [2007]) 125

- "De Grote of Onze Lieve Vrouwekerk te Dordrecht". Bulletin KNOB (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 2021-01-21. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- "Building". Vrienden van de Grote Kerk Dordrecht. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- "De brand duurde vijf dagen". Algemeen Dagblad (in Dutch). 9 May 2017. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- "Gemeente Dordrecht - Gemeente Dordrecht". dordrecht.nl. Archived from the original on 2008-12-17.

- "Synod of Dort". Britannica Online Encyclopædia. Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- "Synode van Dordrecht - Kerk in Dordt". kerkindordt.nl. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- Vandergugten, S. (1989). "The Arminian Controversy and the Synod of Dort". Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- "Remonstrants". Christian Classics Ethereal Library. 2004. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- Sigmond, Kees; De Meer, Sjoerd (2013). Een zoete belofte Suikernijverheid in Dordrecht (17de-19de eeuw). Historische Vereniging Oud-Dordrecht.

- Koopmans, Carolien (1992). Dordrecht 1811-1914: een eeuw demografische en economische geschiedenis. Verloren, Hilversum. ISBN 9065504052.

- Samenstelling van de bevolking van Dordrecht per 1 januari 2005 volgens inventarisatie van het Sociaal Geografisch Bureau van Dordrecht

- Kerngegevens Dordrecht 1.1.2008 Archived September 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Onderzoekcentrum Dordrecht, opgehaald 21 okotober 2009

- "Dordt in Stoom". Dordtinstoom.nl. Archived from the original on 2013-05-06. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "Uitreiking Nationale Evenementenprijzen in Dordrecht". Nieuwsbank.nl. 2004-05-13. Archived from the original on 2012-02-16. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "Home - Gemeente Dordrecht". Vertelhetderaad.nl. 2010-06-09. Archived from the original on 2012-02-25. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "Home - Gemeente Dordrecht". Vertelhetderaad.nl. 2010-06-09. Archived from the original on 2012-02-25. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "Dordt in Stoom". Dordtinstoom.nl. Archived from the original on 2013-03-13. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "Home - Gemeente Dordrecht". Cms.dordrecht.nl. 2010-06-09. Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "Kerstmarkt Dordrecht - De grootste en meest sfeervolle Kerstmarkt van Nederland". Kerstmarktdordrecht.nl. Archived from the original on 2013-05-20. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "Wantijpop". Wantijpop.nl. Archived from the original on 2013-04-07. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "Leuke straten in Dordrecht - Winkelen Dordrecht - Informatie over winkelen in Dordrecht". Youropi.com. Archived from the original on 2013-06-27. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "Bestuursinformatiesysteem Gemeente Dordrecht - Orgaan". Dordrecht.nl. Archived from the original on 2012-09-19. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "Partnersteden". dordrecht.nl. Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- "Lijn & halte informatie - Waterbus". www.waterbus.nl. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 05 (11th ed.). 1911.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 07 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Crowe, Joseph Archer (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). pp. 677–678.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). 1911.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 298.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). 1911.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). 1911.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). 1911.

- IMDb Database Archived 2017-02-17 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 13 February 2020

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). 1911.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. VII (9th ed.). 1878. p. 145.

- Sime, James (1878). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. VII (9th ed.). pp. 145–146.

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography – via Wikisource.

Sources

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 08 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 424.

- Lourens, Piet; Lucassen, Jan (1997). Inwonertallen van Nederlandse steden ca. 1300–1800. Amsterdam: NEHA. ISBN 9057420082.

External links

Dordrecht travel guide from Wikivoyage

Dordrecht travel guide from Wikivoyage- Official website

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)