Dorygnathus

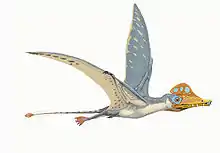

Dorygnathus ("spear jaw") was a genus of rhamphorhynchid pterosaur that lived in Europe during the Early Jurassic period, when shallow seas flooded much of the continent. It had a short (1.5 meters (4.9 feet)) wingspan, and a relatively small triangular sternum, which is where its flight muscles attached. Its skull was long and its eye sockets were the largest opening therein. Large curved fangs that "intermeshed" when the jaws closed featured prominently at the front of the snout while smaller, straighter teeth lined the back.[1] Having two or more morphs of teeth, a condition called heterodonty, is rare in modern reptiles but more common in basal ("primitive") pterosaurs. The heterodont dentition in Dorygnathus is consistent with a piscivorous (fish-eating) diet.[1] The fifth digit on the hindlimbs of Dorygnathus was unusually long and oriented to the side. Its function is not certain, but the toe may have supported a membrane like those supported by its wing-fingers and pteroids. Dorygnathus was according to David Unwin related to the Late Jurassic pterosaur Rhamphorhynchus and was a contemporary of Campylognathoides in Holzmaden and Ohmden.[1]

| Dorygnathus Temporal range: Early Jurassic, | |

|---|---|

_at_G%C3%B6teborgs_Naturhistoriska_Museum_9000.jpg.webp) | |

| A cast of UUPM R 156 in Göteborgs Naturhistoriska Museum, a specimen sold by Bernhard Hauff to the University of Uppsala in 1925 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Family: | †Rhamphorhynchidae |

| Subfamily: | †Rhamphorhynchinae |

| Genus: | †Dorygnathus Wagner, 1860 |

| Type species | |

| †Ornithocephalus banthensis Theodori, 1830 | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

Discovery

The first remains of Dorygnathus, isolated bones and jaw fragments from the Schwarzjura, the Posidonia Shale dating from the Toarcian, were discovered near Banz, Bavaria and in 1830 described by Carl Theodori as Ornithocephalus banthensis; the specific name referring to Banz.[2] In 1831 however, Theodori reassigned the species to the genus Pterodactylus, therefore creating P. banthensis.[3] The holotype, a lower jaw, is specimen PSB 757. The fossils were studied by Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer in 1831[4] and again by Theodori in 1852 when he referred them to the genus Rhamphorhynchus instead of Pterodactylus.[5] In this period a close affinity was assumed with a pterosaur known from Britain, later named Dimorphodon. Some fossils were sent to a professor of paleontology in Munich named Johann Andreas Wagner. It was he who, having studied new finds by Albert Oppel in 1856 and 1858,[6][7] after Richard Owen had named Dimorphodon concluded that the German type was clearly different and that therefore a new genus of pterosaur should be erected, which he formally named Dorygnathus in 1860, from Greek dory, "spear" and gnathos, "jaw".[8] Much more complete remains have been found since in other German locales and especially in Württemberg, including Holzmaden, Ohmden, and Zell.[1] One specimen, SMNS 81840, has in 1978 been dug up in Nancy, France.[9] Dorygnathus fossils were often found in the spoil heaps where unusable rock was dumped from slate quarries worked by local farmers.[10] Most fossils were found in two major waves, one during the twenties, the other during the eighties of the twentieth century. Since then the rate of discovery has slowed considerably because the demand for slate has strongly diminished and many small quarries have closed. At present over fifty specimens have been collected, many of them are preserved in the collection of the State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart, as by law paleontological finds in Baden-Württemberg are property of this Bundesland. Due to the excellent preserval of the later found fossils, Dorygnathus has generated much interest by pterosaur researchers, important studies having been dedicated to the species by Felix Plieninger,[11] Gustav von Arthaber,[12] and more recently Kevin Padian.[13]

In 1971 Rupert Wild described and named a second species: Dorygnathus mistelgauensis,[14] based on a specimen collected in a brick pit near the railway station of Mistelgau, to which the specific name refers, by teacher H. Herppich, who donated it to the private collection of Günther Eicken, a local amateur paleontologist at Bayreuth, where it still resides. As a result, the exemplar has no official inventory number. The fossil comprises a shoulder-blade with wing, a partial leg, a rib and a caudal vertebra. Wild justified the creation of a new species name by referring to the great size, with an about 50% larger wingspan than with a typical specimen; the short lower leg and the long wing.

Padian in 2008 pointed out that D. banthensis specimen MBR 1977.21, the largest then known, has with a wingspan of 169 centimetres an even larger size; that wing and lower leg proportions are rather variable in D. banthensis and that the geological age is comparable. He concluded that D. mistelgauensis is a subjective junior synonym of D. banthensis.

Description

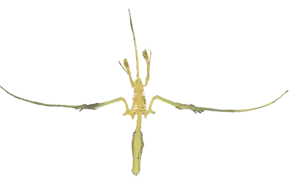

Dorygnathus in general has the build of a basal, i.e. non-pterodactyloid pterosaur: a short neck, a long tail and short metacarpals — although for a basal pterosaur the neck and metacarpals of Dorygnathus are again relatively long. The skull is elongated and pointed. The largest known cranium, that of specimen MBR 1920.16 prepared by Bernard Hauff in 1915 and eventually acquired by the Natural History Museum of Berlin, has a length of sixteen centimetres. In the skull the eye socket forms the largest opening, larger than the fenestra antorbitalis that is clearly separated from the slit-like bony naris. No bony crest is visible on the rather straight top of the skull or snout. The lower jaws are thin at the back but deeper toward the front where they fuse into the symphysis ending in a toothless point after which the genus has been named. In MBR 1920.16, the mandibula as a whole has a length of 147 millimetres.[15]

In the lower jaws the first three pairs of teeth are very long, sharp and pointing outwards and forwards. They contrast with a row of eight or more upright-standing much smaller teeth that gradually diminish in size towards the back of the lower jaw. No such extreme contrast exists in the upper jaws, but the four teeth in the premaxilla are longer than the seven in the maxilla that again become smaller posteriorly. The total number of teeth is thus at least 44. The long upper and lower front teeth interlaced when the beak was closed; due to their extreme length they then projected considerably beyond the upper and lower margins of the head.

According to Padian, eight cervical, fourteen dorsal, three or four sacral and twenty-seven or twenty-eight caudal vertebrae are present. The exceptional fourth sacral is the first of the normal caudal series. The number of caudals is not certain because their limits are obscured by long thread-like extensions, stiffening the tail. The cervical vertebrae are rather long and strongly built, their upper surface having a roughly square cross-section. They carry double-headed thin cervical ribs. The dorsal vertebrae are more rounded with flat spines; the first three or four carry ribs that contact the sternal ribs; the more posterior ribs contact the gastralia. The first five or six, rather short, caudal vertebrae form a flexible tail base. To the back the caudals grow longer and are immobilised by their intertwining extensions with a length of up to five vertebrae which together surround the caudals with a bony network, allowing the tail to function as a rudder. The breastbone is triangular and relatively small; Padian has suggested it may have been extended at its back with a cartilaginous tissue. It is connected to the coracoid which in older individuals is fused to the longer scapula forming a saddle-shaped shoulder joint. The humerus has a triangular deltopectoral crest and is pneumatised. The lower arm is 60% longer than the upper arm. From the five carpal bones in the wrist a short but robust pteroid points towards the neck, in the living animal a support for a flight membrane, the propatagium. The first three metacarpals are connected to three small fingers, equipped with short but strongly curved claws; the fourth to the wing finger, in which the second or third phalanx is the longest; the first or fourth the shortest. The wing finger supports the main flight membrane.

In the pelvis, the ilium, ischium and pubis are fused. The ilium is elongated with a length of six vertebrae. The lower leg, in which the lower two thirds of the tibia and fibula of adult specimens are fused, is a third shorter than the thighbone, the head of which makes an angle of 45° with its shaft. The proximal tarsals are never fused in a separate astragalocalcaneum; a tibiotarsus is formed. The third metatarsal is the longest; the fifth is connected to a toe of which the second phalanx shows a 45° bend and has a blunt and broad end; it perhaps supported a membrane between the legs, a cruropatagium.

In some specimens, soft parts have been preserved but these are rare and limited, providing little information. It is unknown whether the tail featured a vane on its end, as with Rhamphorhynchus. However, Ferdinand Broili reported the presence of hairs in specimen BSP 1938 I 49,[16] an indication that Dorygnathus also had pycnofibers or feathers and an elevated metabolism, as is presently assumed for all pterosaurs.

Phylogeny

The affinity between Dorygnathus and Dimorphodon, assumed by early researchers, was largely based on a superficial resemblance in tooth form. Baron Franz Nopcsa in 1928 assigned the species to the Rhamphorhynchinae,[17] which was confirmed by Peter Wellnhofer in 1978.[18] Modern exact cladistic analyses of the relationships of Dorygnathus have not resulted in a consensus. David Unwin in 2003 found that it belonged to the clade Rhamphorhynchinae,[19] but analyses by Alexander Kellner resulted in a much more basal position,[20] below Dimorphodon or Peteinosaurus. Padian, using a comparative method, in 2008 concluded that Dorygnathus was close to Scaphognathus and Rhamphorhynchus in the phylogenetic tree but also that these species were forming a series of successive off-shoots, meaning that they would not be united in a separate clade. This was again contradicted by the results of a cladistic study by Brian Andres in 2010 showing that Dorygnathus was part of a monophyletic Rhamphorhynchinae.[21] The following cladogram shows the position of Dorygnathus according to Andres:

| Rhamphorhynchinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Dorygnathus is commonly thought to have been piscivorous, catching fish and other slippery prey with its long teeth. This is supported by the fact that their fossils have been found in marine deposits of the Posidonia Shale, where it is found alongside the much rarer pterosaur Campylognathoides. Some Dorygnathus specimens have teeth exhibiting enamel wear consistent with the consumption of hard food items.[22] This could suggest these pterosaurs were occasionally durophagous, eating hard-shelled prey such as molluscs or crustaceans. Very young juveniles of Dorygnathus are unknown, the smallest discovered specimen having a wingspan of sixty centimetres; perhaps they were unable to venture far over open sea. Padian concluded that Dorygnathus after a relatively fast growth in its early years, faster than any modern reptile of the same size, kept slowly growing after having reached sexual maturity, which would have resulted in exceptionally large individuals with a 1.7 metres (5.6 feet) wingspan.

See also

References

- "Dorygnathus." In: Cranfield, Ingrid (ed.). The Illustrated Directory of Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Creatures. London: Salamander Books, Ltd. Pp. 292-295.

- Theodori, C. (1830). "Knochen vom Pterodactylus aus der Liasformation von Banz", Frorieps Notizen für Natur- und Heilkunde, n. 632, 101pp

- Theodori, C. (1831). "Ueber die Knochen vom Genus Pterodactylus aus der Liasformation der Gegend von Banz", Okens Isis, 3: 276–281

- Meyer, H. von (1831). "Über Macrospondylus und Pterodactylus", Nova Acta Academia Caesarae Leopold-Carolina Germania Naturali Curiae, 15: 198–200

- Theodori, C. (1852). "Ueber die Pterodactylus-Knochen im Lias von Banz", Berichte des Naturforschenden Vereins Bamberg, 1: 17–44

- Oppel, A. (1856). "Die Juraformation", Jahreshefte des Vereins für Vaterländische Naturkunde in Württemberg, 12

- Oppel, A. (1858). "Die Geognostische Verbreitung der Pterodactylen", Jahreshefte der Vereins der vaterländische Naturkunde in Württemberg, 1858, Vorträge 8, 55 pp

- Wagner, A. (1860). "Bemerkungen über die Arten von Fischen und Sauriern, Welche im untern wie im oberen Lias zugleich vorkommen sollen", Sitzungsberichte der königlichen Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, mat.- physikalische Classe, p. 36-52

- Dominique Delsate & Rupert Wild. (2000). "Première Découverte d'un Reptile volant determinable (Pterosauria, Dorygnathus cf banthensis) du Toracien inférieur (Jurassique inférieur) de Nancy (Lorraine, France)", Bulletin de l'Académie et de la Société lorraines des sciences, 2000, 39: 1-4

- Keller, Thomas (1985). "Quarrying and Fossil Collecting in the Posidonienschiefer (Upper Liassic) around Holzmaden, Germany", Geological Curator, 4(4): 193-198

- Plieninger, F. (1907). "Die Pterosaurier der Juraformation Schwabens", Palaeontographica, 53: 209–313

- Arthaber, G.E. von (1919). "Studien über Flugsaurier auf Grund der Bearbeitung des Wiener Exemplares von Dorygnathus banthensis Theod. sp.", Denkschriften der Akademie der Wissenschaften Wien, Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Klasse, 97: 391–464

- Padian, K. & Wild, R. (1992). "Studies of Liassic Pterosauria, I. The holotype and referred specimens of the Liassic Pterosaur Dorygnathus banthensis (Theodori) in the Petrefaktensammlung Banz, Northern Bavaria", Palaeontographica Abteilung A, 225: 55-79

- Wild, R. (1971). "Dorygnathus mistelgauensis n. sp., ein neuer Flugsaurier aus dem Lias Epsilon von Mistelgau (Frankischer Jura)" — Geol. Blatter NO-Bayern, 21(4): 178-195

- Kevin Padian (2008). The Early Jurassic Pterosaur Dorygnathus Banthensis(Theodori, 1830). Special Papers in Palaeontology No. 80, The Palaeontological Association, London

- Broili, F. (1939) "Ein Dorygnathus mit Hautresten", Sitzungs-Berichte der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Abteilung, 1939: 129–132

- Nopcsa, F. v. (1928). "The genera of reptiles". Palaeobiologica, 1: 163-188

- Wellnhofer, P. (1978). Pterosauria. Handbuch der Palaeoherpetologie, Teil 19. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart

- Unwin, D. M. (2003). "On the phylogeny and evolutionary history of pterosaurs". Pp. 139-190 in: Buffetaut, E. and Mazin, J.-M., eds. Evolution and Palaeobiology of Pterosaurs. Geological Society Special Publications 217. Geological Society of London

- Kellner, A. W. A. (2003). "Pterosaur phylogeny and comments on the evolutionary history of the group". Pp. 105-137 in: Buffetaut, E. and Mazin, J.-M., eds. Evolution and Palaeobiology of Pterosaurs. Geological Society Special Publications 217. Geological Society of London

- Brian Andres; James M. Clark & Xu Xing. (2010). "A new rhamphorhynchid pterosaur from the Upper Jurassic of Xinjiang, China, and the phylogenetic relationships of basal pterosaurs", Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 30(1): 163-187

- Ősi, Attila (June 2011). "Feeding-related characters in basal pterosaurs: implications for jaw mechanism, dental function and diet: Feeding-related characters in pterosaurs". Lethaia. 44 (2): 136–152. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2010.00230.x.